Desogestrel

Desogestrel, sold under the brand names Cerazette and Mircette among many others, is a progestin medication which is used in birth control pills for women.[1][5] It is also used in the treatment of menopausal symptoms in women.[1] The medication is available and used alone or in combination with an estrogen.[1][5] It is taken by mouth.[1]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Azalia, Cerazette, Desogen, Marvelon, Mercilon, Mircette, Novynette, others |

| Other names | DSG; ORG-2969; 3-Deketo-11-methylene-17α-ethynyl-18-methyl-19-nortestosterone; 11-Methylene-17α-ethynyl-18-methylestr-4-en-17β-ol |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Micromedex Detailed Consumer Information |

| MedlinePlus | a601050 |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth[1] |

| Drug class | Progestogen; Progestin |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 76% (range 40–100%)[2][3] |

| Protein binding | Desogestrel: 99%:[4] • Albumin: 99% Etonogestrel: 95–98%:[1][5] • Albumin: 65–66% • SHBG: 30–32% • Free: 2–5% |

| Metabolism | Liver, intestines (5α- and 5β-reductase, cytochrome P450 enzymes, others)[5] |

| Metabolites | • Etonogestrel[5][1][2] • Others[4][5][2] |

| Elimination half-life | Desogestrel: 1.5 hours[4] Etonogestrel: 21–38 hrs[4][6] |

| Excretion | Urine: 50%[4] Feces: 35%[4] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.053.555 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C22H30O |

| Molar mass | 310.481 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 109 to 110 °C (228 to 230 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Side effects of desogestrel include menstrual irregularities, headaches, nausea, breast tenderness, mood changes, acne, increased hair growth, and others.[1] Desogestrel is a progestin, or a synthetic progestogen, and hence is an agonist of the progesterone receptor, the biological target of progestogens like progesterone.[1][5] It has very weak androgenic and glucocorticoid activity and no other important hormonal activity.[5] The medication is a prodrug of etonogestrel (3-ketodesogestrel) in the body.[1][5]

Desogestrel was discovered in 1972 and was introduced for medical use in Europe in 1981.[7][4][8] It became available in the United States in 1992.[9][10][11] Desogestrel is sometimes referred to as a "third-generation" progestin.[12] Along with norethisterone, it is one of the only progestins that is widely available as a progestogen-only "mini pill" for birth control.[13][14] Desogestrel is marketed widely throughout the world.[15] It is available as a generic medication.[16] In 2017, the version with ethinylestradiol was the 164th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than three million prescriptions.[17][18]

Medical uses

Desogestrel is used in hormonal contraception in women, specifically in birth control pills.[1] It is used alone in progestogen-only pills ("mini pills") and in combination with the estrogen ethinylestradiol in combined oral contraceptive pills.[1] Along with norethisterone, it is one of the only progestins that is widely used as a progestogen-only "mini pill".[13][14] It is also the only newer-generation progestin with reduced androgenic activity that is used in such formulations.[13][14] In addition to hormonal contraception, desogestrel has been used in combination with estrogens such as estradiol as a component of menopausal hormone therapy.[1] The medication has also been used in the treatment of endometriosis.[12]

Available forms

Desogestrel is available alone in the form of 75 μg oral tablets and at a dose of 150 μg in combination with 20 or 30 μg ethinylestradiol in oral tablets.[19] These formulations are all indicated specifically for contraceptive purposes.[19]

Contraindications

Contraindications of desogestrel include:[20]

- Allergy to desogestrel or any other ingredients

- Active thrombosis (deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism)

- Jaundice or severe liver disease

- Hormone-sensitive cancers (e.g., breast cancer)

- Unexplained vaginal bleeding

Desogestrel is not indicated for use in pregnancy.[20] It is not contraindicated during lactation and breastfeeding.[21]

Side effects

Common side effects of desogestrel may include menstrual irregularities, amenorrhea, headaches, nausea, breast tenderness, and mood changes (e.g., depression), as well as weight gain, acne, and hirsutism.[1][22] However, it has also been reported to not adversely affect weight.[9] In addition, acne and hirsutism are negligible when combined with ethinylestradiol, and this combination can actually be used to treat such symptoms.[1] Desogestrel can also cause changes in total, LDL, and HDL cholesterol.[1] Uncommon side effects of desogestrel may include vaginal infection, contact lens intolerance, vomiting, hair loss, dysmenorrhea, ovarian cysts, and fatigue, while rare side effects include rash, urticaria, and erythema nodosum.[22] Breast discharge, ectopic pregnancies, and aggravation of angioedema may also occur with desogestrel.[22] Serious side effects of combined oral contraceptives containing desogestrel may include venous thromboembolism, arterial thromboembolism, hormone-dependent tumors (e.g., liver tumors, breast cancer), and melasma.[22]

Overdose

No serious harmful effects have been reported with overdose of desogestrel.[20][22] Symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, and, in young girls, slight vaginal bleeding.[20][22] In safety studies, dosages of up to 750 μg/day desogestrel in women showed no adverse effects on laboratory and various other parameters and produced no reported subjective side effects.[4] There is no antidote to desogestrel overdose and treatment should be based on symptoms.[22]

Interactions

Inducers of liver enzymes can increase the metabolism of desogestrel and etonogestrel and reduce their circulating levels.[22] This may result in contraceptive failure.[22] Examples of liver enzyme inducers include barbiturates (e.g., phenobarbital), bosentan, carbamazepine, efavirenz, phenytoin, primidone, rifampicin, and possibly also felbamate, griseofulvin, oxcarbazepine, rifabutin, St. John's Wort, and topiramate.[22] Many antivirals for HIV/AIDS and HCV, such as boceprevir, nelfinavir, nevirapine, ritonavir, and telaprevir, may increase or decrease levels of desogestrel and etonogestrel.[22] CYP3A4 inhibitors including strong inhibitors like clarithromycin, itraconazole, and ketoconazole and moderate inhibitors like diltiazem, erythromycin, and fluconazole may increase levels of desogestrel and etonogestrel.[22] Hormonal contraceptives may interfere with the metabolism of other drugs, resulting in increased levels (e.g., ciclosporine) or decreased levels (e.g., lamotrigine).[22]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Desogestrel is a prodrug of etonogestrel (3-ketodesogestrel), and, via this active metabolite, it has progestogenic activity, antigonadotropic effects, very weak androgenic activity, very weak glucocorticoid activity, and no other hormonal activity.[23][1][5]

| Compound | PR | AR | ER | GR | MR | SHBG | CBG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desogestrel | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Etonogestrel (3-keto-DSG) | 150 | 20 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 15 | 0 |

| 3α-Hydroxydesogestrel | 5 | 0 | 0 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 3β-Hydroxydesogestrel | 13 | 3 | 2 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 5α-Dihydroetonogestrel | 9 | 17 | 0 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 3α-Hydroxy-5α-dihydroetonogestrel | 0 | 0 | 0 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| 3β-Hydroxy-5α-dihydroetonogestrel | 1 | 0 | 1 | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Notes: Values are percentages (%). Reference ligands (100%) were promegestone for the PR, metribolone for the AR, E2 for the ER, DEXA for the GR, aldosterone for the MR, DHT for SHBG, and cortisol for CBG. Sources: [24][23] | |||||||

Progestogenic activity

Desogestrel is a progestogen, or an agonist of the progesterone receptor (PR).[1] It is an inactive prodrug of etonogestrel with essentially no affinity for the PR itself (about 1% of that of promegestone).[1][5][25] Hence, etonogestrel is exclusively responsible for the effects of desogestrel.[2] Etonogestrel has about 150% of the affinity of promegestone and 300% of the affinity of progesterone for the PR.[5] Desogestrel (via etonogestrel) is a very potent progestogen and inhibits ovulation at very low doses, in the low microgram range.[1] The effective minimum dosage for inhibition of ovulation is 60 μg/day desogestrel (alone, not in combination with an estrogen).[1][5] However, some studies in combination with oral estradiol have suggested that higher doses may be necessary.[26] Desogestrel and etonogestrel are among the most potent progestogens available, along with gestodene and levonorgestrel (which have effective ovulation-inhibiting dosages 40 μg/day and 60 μg/day, respectively).[23] Oral desogestrel is clinically on the order of 5,000 times more potent than oral micronized progesterone (which has an effective ovulation-inhibiting dosage of more than 300 mg/day) in humans.[23]

Due to its progestogenic activity, desogestrel has potent functional antiestrogenic effects in certain tissues.[5][23] It dose-dependently antagonizes the effects of ethinylestradiol on the vaginal epithelium, cervical mucus, and endometrium, with marked progestogenic effects occurring at a dosage of 60 μg/day.[5] There is a rise in body temperature in some women at 30 μg/day and in all women at 60 μg/day.[5] Desogestrel also has antigonadotropic effects, which are similarly due to its progestogenic activity.[5][23] The contraceptive effects of desogestrel in women are mediated not only by prevention of ovulation via its antigonadotropic effects but also by its marked progestogenic and antiestrogenic effects on cervical mucus and the endometrium.[5]

Aside from its progestogenic activity, desogestrel also has some off-target hormonal activity at other steroid hormone receptors (see below).[4][23] However, these activities are relatively weak, and desogestrel is said to be one of the most selective and pure progestogens used in oral contraceptives.[4]

Antigonadotropic effects

Desogestrel has antigonadotropic effects via its progestogenic activity, similarly to other progestogens.[5][23] It has been found to reduce testosterone levels by 15% in women at a dosage of 125 μg/day.[5] In addition, desogestrel has been extensively investigated as an antigonadotropin at dosages of 150 to 300 μg/day in combination with testosterone in male contraceptive regimens.[5] One study found that 150 μg/day and 300 μg/day desogestrel alone in healthy young men suppressed luteinizing hormone (LH) levels by about 35% and 42%, respectively; follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels by about 47% and 55%, respectively; and testosterone levels by about 59% and 68%, respectively.[27] LH levels were suppressed maximally by desogestrel within 3 days, whereas 14 days were necessary for maximal suppression of FSH and testosterone levels.[27] A previous study by the same authors found that increasing the dosage of desogestrel from 300 μg/day to 450 μg/day resulted in no further suppression of gonadotropin concentrations.[27] The addition of a low dose of 50 or 100 mg/week intramuscular testosterone enanthate after 3 weeks increased testosterone levels and further suppressed LH and FSH levels, to the limits of assay detection (i.e., to undetectable or near-undetectable levels), in both the 150 μg/day and 300 μg/day desogestrel groups.[27] Upon cessation of treatment, levels of LH, FSH, and testosterone all recovered to baseline values within 4 weeks.[27]

Androgenic activity

Etonogestrel has about 20% of the affinity of metribolone and 50% of the affinity of levonorgestrel for the androgen receptor (AR) while desogestrel has no affinity for this receptor.[1][5] The 5α-reduced metabolite of etonogestrel, 5α-dihydroetonogestrel (3-keto-5α-dihydrodesogestrel), also has some affinity for the AR (about 17% of that of metribolone).[5] Desogestrel (via etonogestrel) has very low androgenic potency, about 1.9 to 7.4% of that of methyltestosterone in animal assays, and hence is considered to be a very weak androgen.[1][5][25] Although etonogestrel has about the same affinity for the AR as norethisterone, due to the relatively increased progestogenic potency and decreased androgenic activity of etonogestrel, the drug has markedly higher selectivity for the PR over the AR than older 19-nortestosterone progestins like norethisterone and levonorgestrel.[4][9][28] Conversely, its selectivity for the PR over the AR is similar to other newer 19-nortestosterone progestins like gestodene and norgestimate.[9][28] It has been estimated that 150 μg/day desogestrel has less than one-sixth of the androgenic effect of 1 mg/day norethisterone (these being common dosages of the drugs used in combined oral contraceptives).[28] Clinical studies with norethisterone even at very high dosages (e.g., 10 to 60 mg/day) have observed only mild androgenic effects in a minority of women including acne, increased sebum production, hirsutism, and slight virilization of female fetuses.[29][30][31][32]

In accordance with its very weak androgenic activity, desogestrel has minimal effects on lipid metabolism and the blood lipid profile, although there may still be some significant changes.[1] Desogestrel also reduces sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) levels by 50% when given to women alone, but when combined with 30 μg/day ethinylestradiol, which in contrast strongly activates SHBG production, there is a 200% increase in SHBG concentrations.[5] Desogestrel may slightly reduce ethinylestradiol-induced increases in SHBG levels.[5] However, at the dosages used in oral contraceptives and in combination with ethinylestradiol, which has potent functional antiandrogenic effects mainly due to increased SHBG levels, the androgenic activity of desogestrel is said to be essentially without any clinical relevance.[5] Indeed, combined oral contraceptives containing ethinylestradiol and desogestrel have been found to significantly decrease free concentrations of testosterone and to possess overall antiandrogenic effects, significantly reducing symptoms of acne and hirsutism in women with hyperandrogenism.[1]

Glucocorticoid activity

Desogestrel has no affinity for the glucocorticoid receptor, but etonogestrel has about 14% of the affinity of dexamethasone for this receptor.[5][23][33] Hence, desogestrel and etonogestrel have weak glucocorticoid activity.[5][23][33] At typical clinical dosages, the glucocorticoid activity of desogestrel is said to be negligible or very weak and hence not clinically relevant.[5][23][33] However, it may nonetheless possibly influence vascular function, with some upregulation of the thrombin receptor observed with etonogestrel in vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro.[5][23][33] This could, in theory, increase coagulation and contribute to an increased risk of venous thromboembolism and atherosclerosis.[23] The affinity of etonogestrel for the glucocorticoid receptor is a product of its C11 methylene substitution, as substitutions at the C11 position are a common feature of corticosteroids and as levonorgestrel, which is etonogestrel without the C11 methylene group (17α-ethynyl-18-methyl-19-nortestosterone), has only 1% of the affinity of dexamethasone for the receptor and hence is considered to have negligible glucocorticoid activity.[23]

| Steroid | Class | TR (↑)a | GR (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dexamethasone | Corticosteroid | ++ | 100 |

| Ethinylestradiol | Estrogen | – | 0 |

| Etonogestrel | Progestin | + | 14 |

| Gestodene | Progestin | + | 27 |

| Levonorgestrel | Progestin | – | 1 |

| Medroxyprogesterone acetate | Progestin | + | 29 |

| Norethisterone | Progestin | – | 0 |

| Norgestimate | Progestin | – | 1 |

| Progesterone | Progestogen | + | 10 |

| Footnotes: a = Thrombin receptor (TR) upregulation (↑) in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). b = RBA (%) for the glucocorticoid receptor (GR). Strength: – = No effect. + = Pronounced effect. ++ = Strong effect. Sources: See template. | |||

Other activities

Desogestrel and etonogestrel have no affinity for the estrogen receptor, and hence have no estrogenic activity.[5][1][4] However, the metabolite 3β-hydroxydesogestrel has weak affinity for the estrogen receptor (about 2% of that of estradiol), although the significance of this is uncertain.[5]

Desogestrel and etonogestrel have no affinity for the mineralocorticoid receptor, and hence have no mineralocorticoid or antimineralocorticoid activity.[5][23]

Desogestrel and etonogestrel show some albeit weak inhibition of 5α-reductase (5.7% inhibition at 0.1 μM, 34.9% inhibition at 1 μM) and cytochrome P450 enzymes (e.g., CYP3A4) (IC50 = 5 μM) in vitro.[5][23]

Desogestrel stimulates the proliferation of MCF-7 breast cancer cells in vitro, an action that is independent of the classical PRs and is instead mediated via the progesterone receptor membrane component-1 (PGRMC1).[34][35] Certain other progestins act similarly in this assay, whereas progesterone acts neutrally.[34][35] It is unclear if these findings may explain the different risks of breast cancer observed with progesterone and progestins in clinical studies.[36]

Pharmacokinetics

The bioavailability of desogestrel has been found to range from 40 to 100%, with an average of 76%.[5][2][3] This significant interindividual variability is comparable to that with norethisterone and levonorgestrel.[2] Peak concentrations of etonogestrel occur about 1.5 hours after a dose while concentrations of desogestrel are very low and have disappeared by 3 hours after a dose.[5] Steady-state levels of etonogestrel are achieved after about 8 to 10 days of daily administration.[1] Accumulation of etonogestrel is thought to be related to progressive inhibition of 5α-reductase and cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (e.g., CYP3A4).[5] The plasma protein binding of desogestrel is 99% and it is bound exclusively to albumin.[4] Etonogestrel is bound 95 to 98% to plasma proteins.[1][5] It is bound about 65 to 66% to albumin and 30 to 32% to SHBG, with 2 to 5% free in the circulation.[1][5] While desogestrel is not bound to SHBG, etonogestrel has relatively high affinity for this plasma protein of 3 to 15% of that of dihydrotestosterone, although this is considerably less than that of the related progestins levonorgestrel and gestodene.[5][2] Neither desogestrel nor etonogestrel are bound by corticosteroid-binding globulin.[5]

Desogestrel is a prodrug of etonogestrel (3-ketodesogestrel) and upon ingestion is rapidly and completely transformed into this metabolite in the intestines and liver.[5][1][2] Hydroxylation of the C3 position of desogestrel catalyzed by cytochrome P450-dependent enzymes, with 3α-hydroxydesogestrel and 3β-hydroxydesogetrel as intermediates, followed by oxidation of the C3 hydroxyl group, is responsible for the transformation.[4][5][2] A small percentage of desogestrel is metabolized into levonorgestrel, which involves the removal of the C11 methylene group.[1] Following further metabolism of etonogestrel, which occurs mainly by reduction of the Δ4-3-keto group (by 5α- and 5β-reductases) and hydroxylation (by monooxygenases), the major metabolite of desogestrel is 3α,5α-tetrahydroetonogestrel.[5] Desogestrel has a very short terminal half-life of about 1.5 hours while etonogestrel has a relatively long elimination half-life of about 21 to 38 hours, reflecting the nature of desogestrel as a prodrug.[4][1][6] Desogestrel and etonogestrel are eliminated exclusively as metabolites 50% in urine and 35% in feces.[4][2]

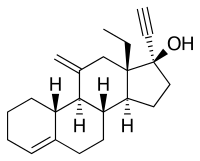

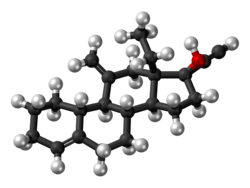

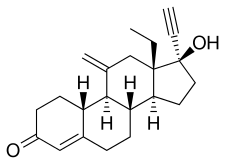

Chemistry

Desogestrel, also known as 3-deketo-11-methylene-17α-ethynyl-18-methyl-19-nortestosterone or as 11-methylene-17α-ethynyl-18-methylestr-4-en-17β-ol, is a synthetic estrane steroid and a derivative of testosterone.[5][37][38] It is more specifically a derivative of norethisterone (17α-ethynyl-19-nortestosterone) and is a member of the gonane (13β-ethylgonane or 18-methylestrane) subgroup of the 19-nortestosterone family of progestins.[5][39][40] Desogestrel is the C3 deketo analogue of etonogestrel and the C3 deketo and C11 methylene analogue of levonorgestrel.[5][41]

Synthesis

A chemical synthesis of desogestrel has been published.[42]

History

Desogestrel was synthesized in 1972 by Organon International in the Netherlands and was first described in the literature in 1975.[7][43][44][45] It was developed following the discovery that C11 substitutions enhance the biological activity of norethisterone.[4] Desogestrel was introduced for medical use in 1981 under the brand names Marvelon and Desogen in the Netherlands.[4][8][5] Along with gestodene and norgestimate, it is sometimes referred to as a "third-generation" progestin based on the time of its introduction to the market.[12] It was the first of the three "third-generation" progestins to be introduced.[4] Although desogestrel was introduced in 1981 and was widely used in Europe from this time, it was not introduced in the United States until 1992.[9][10][11]

Society and culture

Generic names

Desogestrel is the generic name of the drug and its INN, USAN, BAN, DCF, DCIT, and JAN.[37][38][15] While under development, it was known as ORG-2969.[37][38][15]

Brand names

Desogestrel is marketed under a variety of brand names throughout the world including Alenvona, Apri, Azalia, Azurette, Caziant, Cerazette, Cerelle, Cesia, Cyclessa, Denise, Desogen, Desirett, Diamilla, Emoquette, Feanolla, Gedarel, Gracial, Kariva, Laurina, Linessa, Marvelon, Mercilon, Mircette, Mirvala, Novynette, Ortho-Cept, Reclipsen, Regulon, Solia, Velivet, and Viorele among others.[38][15]

Availability

Desogestrel is available widely throughout the world, including in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Ireland, many other European countries, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Latin America, South, East, and Southeast Asia, and elsewhere in the world.[15][46] In the United States, it is available only in combination with ethinylestradiol as a combined oral contraceptive; it is not available alone and is not approved for any other indications in this country.[21][46]

Controversy

In February 2007, the consumer advocacy group Public Citizen released a petition requesting that the Food and Drug Administration ban oral contraceptives containing desogestrel in the United States, citing studies going as far back as 1995 that suggest the risk of dangerous blood clots is doubled for women on such pills in comparison to other oral contraceptives.[47] In 2009, Public Citizen released a list of recommendations that included numerous alternative, second-generation birth control pills that women could take in place of oral contraceptives containing desogestrel.[48] Most of those second-generation medications have been on the market longer and have been shown to be as effective in preventing unwanted pregnancy, but with a lower risk of blood clots.[48] Medications cited specifically in the petition include Apri-28, Cyclessa, Desogen, Kariva, Mircette, Ortho-Cept, Reclipsen, Velivet, and some generic pills, all of which contain desogestrel in combination with ethinylestradiol.[47] Medications containing desogestrel as the only active ingredient (as opposed to being used in conjunction with ethinylestradiol, like in combined oral contraceptives) do not show an increased thrombosis risk and are therefore safer than second-generation birth-control pills in regards to thrombosis.[49]

Research

Desogestrel has been studied extensively as an antigonadotropin for use in combination with testosterone as a hormonal contraceptive in men.[50][51] Such combinations have been found to be effective in producing reversible azoospermia in most men and reversible azoospermia or severe oligozoospermia in almost all men.[50]

References

- Stone SC (1995). "Desogestrel". Clin Obstet Gynecol. 38 (4): 821–8. doi:10.1097/00003081-199538040-00017. PMID 8616978.

- McClamrock HD, Adashi EY (1993). "Pharmacokinetics of desogestrel". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 168 (3 Pt 2): 1021–8. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(93)90332-D. PMID 8447355.

- Fotherby K (August 1996). "Bioavailability of orally administered sex steroids used in oral contraception and hormone replacement therapy". Contraception. 54 (2): 59–69. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(96)00136-9. PMID 8842581.

- Benno Clemens Runnebaum; Thomas Rabe; Ludwig Kiesel (6 December 2012). Female Contraception: Update and Trends. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 156–163. ISBN 978-3-642-73790-9.

- Kuhl H (1996). "Comparative pharmacology of newer progestogens". Drugs. 51 (2): 188–215. doi:10.2165/00003495-199651020-00002. PMID 8808163.

- Mosby's GenRx: A Comprehensive Reference for Generic and Brand Prescription Drugs. Mosby. 2001. p. 687. ISBN 978-0-323-00629-3.

The elimination half-life for 3-keto-desogestrel is approximately 38 ± 20 hours at steady state.

- Kuhl H (2011). "Pharmacology of progestogens" (PDF). Journal für Reproduktionsmedizin und Endokrinologie-Journal of Reproductive Medicine and Endocrinology. 8 (Special Issue 1): 157–176.

Desogestrel was synthesized in 1972 at Organon [...]

- Jeremy A. Holtsclaw (2007). Progress Towards the Total Synthesis of Desogestrel and the Development of a New Chiral Dihydroimidazol-2-ylidene Ligand. University of Michigan. p. 25.

In 1981, desogestrel was marketed as a new low dose oral contraceptive under the trade names Marvelon® and Desogen®.32

- Kaplan B (1995). "Desogestrel, norgestimate, and gestodene: the newer progestins". Ann Pharmacother. 29 (7–8): 736–42. doi:10.1177/106002809502907-817. PMID 8520092.

- Susan G. Kornstein; Anita H. Clayton (15 December 2004). Women's Mental Health: A Comprehensive Textbook. Guilford Press. pp. 114–. ISBN 978-1-59385-144-6.

- Archer DF (1994). "Clinical and metabolic features of desogestrel: a new oral contraceptive preparation". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 170 (5 Pt 2): 1550–5. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(94)05018-0. PMID 8178905.

- Howard J.A. Carp (9 April 2015). Progestogens in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Springer. pp. 112, 136. ISBN 978-3-319-14385-9.

- Grimes DA, Lopez LM, O'Brien PA, Raymond EG (2013). "Progestin-only pills for contraception". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (11): CD007541. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007541.pub3. PMID 24226383.

- Hussain SF (2004). "Progestogen-only pills and high blood pressure: is there an association? A literature review". Contraception. 69 (2): 89–97. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2003.09.002. PMID 14759612.

- "Desogestrel".

- "Generic Desogen Availability".

- "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- "Desogestrel; Ethinyl Estradiol - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Michael Freissmuth; Stefan Böhm (9 March 2012). Pharmakologie und Toxikologie: Von den molekularen Grundlagen zur Pharmakotherapie. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 572–. ISBN 978-3-642-12353-5.

- https://www.drugs.com/uk/pdf/leaflet/1016645.pdf

- "Desogestrel use while Breastfeeding".

- "Cerazette 75 microgram film-coated tablet - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (eMC)".

- Kuhl H (2005). "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration" (PDF). Climacteric. 8 Suppl 1: 3–63. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875. PMID 16112947.

- Kuhl H (1990). "Pharmacokinetics of oestrogens and progestogens". Maturitas. 12 (3): 171–97. doi:10.1016/0378-5122(90)90003-o. PMID 2170822.

- Thomas L. Lemke; David A. Williams (2008). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1316–. ISBN 978-0-7817-6879-5.

- Bastianelli C, Farris M, Rosato E, Brosens I, Benagiano G (November 2018). "Pharmacodynamics of combined estrogen-progestin oral contraceptives 3. Inhibition of ovulation". Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 11 (11): 1085–1098. doi:10.1080/17512433.2018.1536544. PMID 30325245.

- Wu FC, Balasubramanian R, Mulders TM, Coelingh-Bennink HJ (1999). "Oral progestogen combined with testosterone as a potential male contraceptive: additive effects between desogestrel and testosterone enanthate in suppression of spermatogenesis, pituitary-testicular axis, and lipid metabolism". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 84 (1): 112–22. doi:10.1210/jcem.84.1.5412. PMID 9920070.

- Collins D (1993). "Selectivity information on desogestrel". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 168 (3 Pt 2): 1010–6. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(93)90330-L. PMID 8447353.

- JACOBSON BD (1962). "Hazards of norethindrone therapy during pregnancy". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 84 (7): 962–8. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(62)90075-3. PMID 14450719.

- Pochi PE, Strauss JS (1965). "Lack of androgen effect on human sebaceous glands with low-dosage norethindrone". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 93 (7): 1002–4. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(65)90162-6. PMID 5843402.

- Curwen, S. (1962). "Virilization with Norethisterone". BMJ. 1 (5289): 1415. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5289.1415-a. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 1958463.

- Kaser DJ, Missmer SA, Berry KF, Laufer MR (2012). "Use of norethindrone acetate alone for postoperative suppression of endometriosis symptoms". J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 25 (2): 105–8. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2011.09.013. PMID 22154396.

- Kuhl H (September 2001). "[New gestagens--advantages and disadvantages]". Ther Umsch (in German). 58 (9): 527–33. doi:10.1024/0040-5930.58.9.527. PMID 11594150.

- Neubauer H, Ma Q, Zhou J, Yu Q, Ruan X, Seeger H, Fehm T, Mueck AO (October 2013). "Possible role of PGRMC1 in breast cancer development". Climacteric. 16 (5): 509–13. doi:10.3109/13697137.2013.800038. PMID 23758160.

- Ruan X, Neubauer H, Yang Y, Schneck H, Schultz S, Fehm T, Cahill MA, Seeger H, Mueck AO (October 2012). "Progestogens and membrane-initiated effects on the proliferation of human breast cancer cells". Climacteric. 15 (5): 467–72. doi:10.3109/13697137.2011.648232. PMID 22335423.

- Trabert B, Sherman ME, Kannan N, Stanczyk FZ (September 2019). "Progesterone and breast cancer". Endocr. Rev. doi:10.1210/endrev/bnz001. PMID 31512725.

- J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 364–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. 2000. pp. 305–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- KD Tripathi (30 September 2013). Essentials of Medical Pharmacology. JP Medical Ltd. pp. 316–. ISBN 978-93-5025-937-5.

- Gretchen M. Lentz (2012). Comprehensive Gynecology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 223–. ISBN 978-0-323-06986-1.

- Sven O. Skouby (15 July 1997). Clinical Perspectives on a New Gestodene Oral Contraceptive Containing 20μg of Ethinylestradiol. CRC Press. pp. 11–. ISBN 978-1-85070-786-8.

- Van Den Broek, A. J.; Van Bokhoven, C.; Hobbelen, P. M. J.; Leemhuis, J. (1975). "11-Alkylidene steroids in the 19-nor series". Recueil des Travaux Chimiques des Pays-Bas. 94 (2): 35. doi:10.1002/recl.19750940203.

- Cullberg, G. (1975, January). ORG-2969, a New Progestational Compound. In Reproduccion (Vol. 2, No. 3-4, pp. 330-330)

- Visser, D., Jager, D., De Jongh, H. P., & Van der Vies, J. (1975). Pharmacological profile of a new orally active progestational steroid: Org 2969. Acta Endocrinologica, 80(Suppl. 199), 405. https://www.popline.org/node/511188

- Viinikka, L., Ylikorkala, O., Nummi, S., Virkkunen, P., Ranta, T., Alapiessa, U., & Vihko, R. (1975). The inhibition of ovulation by a new and potent progestin: a clinical study. Acta Endocrinologica, 80(199), 303. https://www.popline.org/node/506048

- "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". United States Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- Public Citizen's Health Research Group: Petition to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to Ban Third Generation Oral Contraceptives Containing Desogestrel due to Increased Risk of Venous Thrombosis HRG Publication #1799, 2007

- Public Citizen Think Twice About Third-Generation Oral Contraceptives and YASMIN Worst Pills, Best Pills, December, 2009

- Lidegaard, Øjvind; Nielsen, Lars Hougaard; Skovlund, Charlotte Wessel; Skjeldestad, Finn Egil; Løkkegaard, Ellen (2011-10-25). "Risk of venous thromboembolism from use of oral contraceptives containing different progestogens and oestrogen doses: Danish cohort study, 2001-9". BMJ. 343: d6423. doi:10.1136/bmj.d6423. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 3202015. PMID 22027398.

Progestogen only products conferred no increased risk of venous thromboembolism, whether taken as low dose norethisterone pills, as desogestrel only pills, or in the form of hormone releasing intrauterine devices.

- Nieschlag E (2010). "Clinical trials in male hormonal contraception" (PDF). Contraception. 82 (5): 457–70. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2010.03.020. PMID 20933120.

- Grimes DA, Lopez LM, Gallo MF, Halpern V, Nanda K, Schulz KF (2012). "Steroid hormones for contraception in men". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD004316. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004316.pub4. PMID 22419294.

Further reading

- Chez RA (1989). "Clinical aspects of three new progestogens: desogestrel, gestodene, and norgestimate". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 160 (5 Pt 2): 1296–300. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(89)80016-X. PMID 2524163.

- op ten Berg M (1991). "Desogestrel: using a selective progestogen in a combined oral contraceptive". Adv Contracept. 7 (2–3): 241–50. doi:10.1007/BF01849414. PMID 1835255.

- op ten Berg M (1991). "Desogestrel: using a selective progestogen in a combined oral contraceptive". Adv Contracept. 7 (2–3): 241–50. doi:10.1007/BF01849414. PMID 1835255.

- Stone S (1993). "Clinical review of a monophasic oral contraceptive containing desogestrel and ethinyl estradiol". Int J Fertil Menopausal Stud. 38 Suppl 3: 117–21. PMID 8260969.

- Collins D (1993). "Selectivity information on desogestrel". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 168 (3 Pt 2): 1010–6. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(93)90330-L. PMID 8447353.

- McClamrock HD, Adashi EY (1993). "Pharmacokinetics of desogestrel". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 168 (3 Pt 2): 1021–8. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(93)90332-D. PMID 8447355.

- Kaunitz AM (1993). "Combined oral contraception with desogestrel/ethinyl estradiol: tolerability profile". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 168 (3 Pt 2): 1028–33. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(93)90333-E. PMID 8447356.

- Archer DF (1994). "Clinical and metabolic features of desogestrel: a new oral contraceptive preparation". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 170 (5 Pt 2): 1550–5. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(94)05018-0. PMID 8178905.

- Sobel NB (1994). "Progestins in preventive hormone therapy. Including pharmacology of the new progestins, desogestrel, norgestimate, and gestodene: are there advantages?". Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 21 (2): 299–319. PMID 7936546.

- Fotherby K (1995). "Twelve years of clinical experience with an oral contraceptive containing 30 micrograms ethinyloestradiol and 150 micrograms desogestrel". Contraception. 51 (1): 3–12. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(94)00010-T. PMID 7750281.

- Kaplan B (1995). "Desogestrel, norgestimate, and gestodene: the newer progestins". Ann Pharmacother. 29 (7–8): 736–42. doi:10.1177/106002809502907-817. PMID 8520092.

- Stone SC (1995). "Desogestrel". Clin Obstet Gynecol. 38 (4): 821–8. doi:10.1097/00003081-199538040-00017. PMID 8616978.

- Stanczyk FZ (1997). "Pharmacokinetics of the new progestogens and influence of gestodene and desogestrel on ethinylestradiol metabolism". Contraception. 55 (5): 273–82. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(97)00030-9. PMID 9220223.

- Lammers P, Blumenthal PD, Huggins GR (1998). "Developments in contraception: a comprehensive review of Desogen (desogestrel and ethinyl estradiol)". Contraception. 57 (5 Suppl): 1S–27S. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(98)00030-4. PMID 9673846.

- Benagiano G, Primiero FM (2003). "Seventy-five microgram desogestrel minipill, a new perspective in estrogen-free contraception". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 997: 163–73. doi:10.1196/annals.1290.019. PMID 14644823.

- Scala C, Leone Roberti Maggiore U, Remorgida V, Venturini PL, Ferrero S (2013). "Drug safety evaluation of desogestrel". Expert Opin Drug Saf. 12 (3): 433–44. doi:10.1517/14740338.2013.788147. PMID 23560561.

- Grandi G, Cagnacci A, Volpe A (2014). "Pharmacokinetic evaluation of desogestrel as a female contraceptive". Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 10 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1517/17425255.2013.844229. PMID 24102478.