Mission Indians

Mission Indians are the indigenous peoples of California who lived in Southern California and were forcibly relocated from their traditional dwellings, villages, and homelands to live and work at 15 Franciscan missions in Southern California and the Asistencias and Estancias established between 1796 and 1823 in the Las Californias Province of the Viceroyalty of New Spain.

| Part of a series on the |

| Spanish missions in California |

|---|

History

Part of a series on |

| Spanish missions in the Americas of the Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| Missions in North America |

| Missions in South America |

| Related topics |

|

|

Spanish explorers arrived on California's coasts as early as the mid-16th century. In 1769 the first Spanish Franciscan mission was built in San Diego. Local tribes were relocated and conscripted into forced labor on the mission, stretching from San Diego to San Francisco. Disease, starvation, over work and torture decimated these tribes.[1] Many were baptized as Roman Catholics by the Franciscan missionaries at the missions.

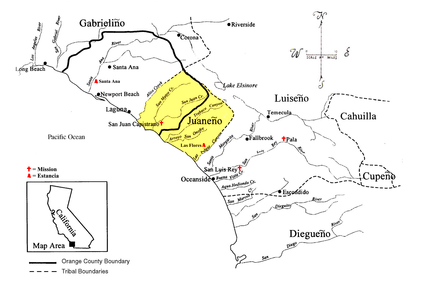

Mission Indians were from many regional Native American tribes; their members were often relocated together in new mixed groups and the Spanish named the Indian groups after the responsible mission. For instance, the Payomkowishum were renamed Luiseños after the Mission San Luis Rey and the Acjachemem were renamed the Juaneños after the Mission San Juan Capistrano.[2] The Catholic priests forbade the Indians from practicing their native culture, resulting in the disruption of many tribes' linguistic, spiritual and cultural practices. With no acquired immunity to the new European diseases and changed cultural and lifestyle demands, the population of Native American Mission Indians suffered high mortality and dramatic decreases especially in the coastal regions where population was reduced by 90 percent between 1769 and 1848.[3]

When Mexico gained its independence in 1834, it assumed control of the Californian missions from the Franciscans, but abuse persisted. Mexico secularized the missions and transferred or sold the lands to other non-Native administrators or owners. Many of the Mission Indians worked on the newly established ranchos with little improvement in their living conditions.[1]

Around 1906 Alfred L. Kroeber and Constance G. Du Bois of the University of California, Berkeley first applied the term "Mission Indians" to Southern California Native Americans as an ethnographic and anthropological label to include those at Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa and south.[4][5]

Reservations

On January 12, 1891 the U.S. Congress passed "An Act for the Relief of the Mission Indians in the State of California" which further sanctioned the original grants of the Mexican government to the natives in southern California and sought to protect their rights while giving railroad corporations a primary interest.[6]

In 1927, Sacramento Bureau of Indian Affairs Superintendent Lafayette A. Dorrington was instructed by Assistant Commissioner E. B. Merritt in Washington D.C. to list tribes in California that Congress had not yet purchased land to be used as reservations. As part of the 1928 California Indian Jurisdictional Act enrollment, Native Americans were asked to identify their “Tribe or Band.” The majority of applicants supplied the name of the mission that they knew their ancestors were associated with. The enrollment was part of a plan to provide reservation lands promised but never fulfilled by 18 non-ratified treaties made in 1851-1852.[7]

Because of the enrollment applications and the native American's association with a specific geographical location, often associated with the Catholic missions, the bands of natives became known as the "mission band" of people associated with a Spanish mission.[7] Some bands also occupy trust lands—Indian Reservations—identified under the Mission Indian Agency. The Mission Indian Act of 1891 formed the administrative Bureau of Indian Affairs unit which governs San Diego County, Riverside County, San Bernardino County, and Santa Barbara County. There is one Chumash reservation in the last county, and more than thirty reservations in the others.

Los Angeles, San Luis Obispo, Ventura and Orange counties do not contain any tribal trust lands. But, resident tribes, including the Tongva in the first and the Juaneño-Acjachemen Nation in the last county (as well as the Coastal Chumash in Santa Barbara County) continue seeking federal Tribal recognition by the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Eleven of the Southern California reservations were included under the early 20th century allotment programs, which broke up communal tribal holdings to assign property to individual households, with individual heads of household and tribal members identified lists such as the Dawes Rolls.

The most important reservations include: the Agua Caliente Reservation in Palm Springs, which occupies alternate sections (approx. 640 acres each) with former railroad grant lands that form much of the city; the Morongo Reservation in the San Gorgonio Pass area; and the Pala Reservation which includes San Antonio de Pala Asistencia (Pala Mission) of the Mission San Luis Rey de Francia in Pala. These and the tribal governments of fifteen other reservations operate casinos today. The total acreage of the Mission group of reservations constitutes approximately 250,000 acres (1,000 km2).

Southern California locations

These tribes were associated with the following Missions, Asisténcias, and Estáncias:

- Mission San Luis Obispo de Tolosa, in San Luis Obispo

- Mission La Purísima Concepción, northeast of Lompoc

- Mission Santa Inés, in Solvang

- Mission Santa Barbara, in Santa Barbara

- Mission San Buenaventura, in Ventura

- Mission San Fernando Rey de España, in Mission Hills (Los Angeles)

- Mission San Gabriel Arcángel, in San Gabriel

- Mission San Juan Capistrano, in San Juan Capistrano

- Mission San Luis Rey de Francia, in Oceanside

- Mission San Diego de Alcalá, in San Diego

- Santa Ysabel Asistencia, founded in 1818 in Santa Ysabel

- San Antonio de Pala Asistencia (Pala Mission), founded in 1816 in eastern San Diego County

- San Bernardino de Sena Estancia, founded in 1819 in Redlands

- Santa Ana Estancia, founded in 1817 in Costa Mesa

- Las Flores Estancia (Las Flores Asistencia), founded in 1823 in Camp Pendleton

Northern California missions

In Northern California, specific tribes are associated geographically with certain missions.[7]

- Mission Dolores in San Francisco (Muwekma Ohlone)

- Mission San Jose in Fremont (Muwekma Ohlone)

- Mission Santa Clara in Santa Clara/San Jose (Muwekma Ohlone)

- Mission Santa Cruz in Santa Cruz (Amah-Mutsun Band of Costanoan Ohlone)

- Mission San Juan Bautista in San Juan Bautista (Amah-Mutsun Band of Costanoan Ohlone)

- Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo in Carmel/Monterey (Esselen nation)

- Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad in Soledad (Esselen nation)

- Mission San Antonio de Padua in Jolon. (Esselen nation and Salinan nation)

Mission tribes

Current mission Indian tribes include the following in Southern California:

- Agua Caliente Band of Mission Indians (Cahuilla)

- Augustine Band of Mission Indians (Cahuilla)

- Barona Band of Mission Indians (Kumeyaay/Diegueño)

- Cabazon Band of Mission Indians (Cahuilla)

- Cahuilla Band of Mission Indians (Cahuilla)

- Campo Band of Mission Indians (Kumeyaay/Diegueño)

- Capitan Grande Band of Mission Indians (Kumeyaay/Diegueño)

- Cuyapaipe Band of Mission Indians (Kumeyaay/Diegueño)

- Giant Rock Band (unrecognized) of Morongo Serrano-Cahuilla.

- Inaja and Cosmit Band of Mission Indians (Kumeyaay/Diegueño)

- Jamul Band of Mission Indians (Kumeyaay/Diegueño)

- Juaneño Band of Mission Indians (Juaneño)

- Laguna Band of Mission Indians of the Laguna Reservation

- La Jolla Band of Mission Indians (Luiseño)

- La Posta Band of Mission Indians (Kumeyaay/Diegueño)

- Las Palmas Band (unrecognized) of Cahuilla.

- Los Coyotes Band of Mission Indians (Cahuilla and Cupeño)

- Manzanita Band of Mission Indians (Kumeyaay/Diegueño)

- Mesa Grande Band of Mission Indians (Kumeyaay/Diegueño)

- Mission Creek Band of Mission Indians - Mission Creek Reservation of Cahuilla.

- Morongo Band of Mission Indians (Cahuilla, Serrano and Cupeño)

- Pala Band of Mission Indians (Cupeño and Luiseño)

- Pauma Band of Mission Indians (Luiseño)

- Pechanga Band of Mission Indians (Luiseño)

- Ramona Band or Village of Mission Indians (Cahuilla)

- San Cayetano Band (unrecognized) of Cahuilla.

- San Manuel Band of Mission Indians (Serrano)

- San Miguel Arcangel,[9] descendants of Mission San Miguel Indians in San Miguel, California.

- San Pasqual Band of Mission Indians (Kumeyaay/Diegueño)

- Santa Rosa Band of Mission Indians (Cahuilla)

- Santa Ynez Band of Mission Indians (Chumash)

- Santa Ysabel Band of Mission Indians (Kumeyaay/Diegueño)

- Soboba Band of Mission Indians (Luiseño)

- Sycuan Band of Mission Indians (Kumeyaay/Diegueño)

- Temecula Band (unrecognized) of Mission Indians (Luiseño and Serrano).

- Torres-Martinez Band of Mission Indians (Cahuilla)

- Twenty-Nine Palms Band of Mission Indians[10] (Chemehuevi with some Cahuilla and Luiseño descent)[11]

Current Mission Indian tribes north of the present day ones listed above, in the Los Angeles Basin, Central Coast, Salinas Valley, Monterey Bay and San Francisco Bay Areas, also were identified with the local Mission of their Indian Reductions in those regions.

See also

- Moravian Indians

- Praying Indians

- Indian Reductions

- California Genocide

- California mission clash of cultures

- Population of Native California

- Native American history of California

- Native Americans in California

- Slavery among Native Americans in the United States

- American Indian reservations in California

- Genízaros

Notes

- Pritzker, 114

- Pritzker, 129

- Davis, Lee. (1996) "California Tribes" in Encyclopedia of North American Indians. Frederick E. Hoxie, editor. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 95. ISBN 0-395-66921-9

- Kroeber 1906:309.

- Du Bois 1904–1906.

- Acts of the Fifty First Congress. Session II. Laws of the United States. Chapter 65 Jan. 12, 1891. 26 Stat., 712. Oklahoma State University Library website Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- Escobar, Lorraine; Field, Les; Leventha, Alan (September 1999). "Understanding the Composition of Costanoan/Ohlone People". Retrieved October 12, 2016.

- Alfred Kroeber, 1925

- Mission San Miguel

- "California Indian Tribes and Their Reservations: Mission Indians." Archived 2010-07-26 at the Wayback Machine SDSU Library and Information Access. (retrieved 6 May 2010)

- "About Us - Tribal History". spotlight29.com. Archived from the original on August 14, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

References

- Du Bois, Constance Goddard. 1904–1906. "Mythology of the Mission Indians", The Journal of the American Folk-Lore Society, Vol. XVII, No. LXVI. p. 185–8 [1904]; Vol. XIX. No. LXXII pp. 52–60 and LXXIII. pp. 145–64. 1906. ("the mythology of the Luiseño and Diegueño Indians of Southern California")

- Kroeber, Alfred. 1906. "Two Myths of the Mission Indians of California", Journal of the American Folk-Lore Society, Vol. XIX, No. LXXV pp. 309–21.

- Pritzker, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

Further reading

- Hutchinson, C. Alan. "The Mexican Government and the Mission Indians of Upper California," The Americas 21(4)1965,pp. 335–362.

- The Mission Indian (newspaper, 5 volumes). Banning, California: B. Florian Hahn. OCLC 15738708

- Phillips, George Harwood, "Indians and the Breakdown of the Spanish Mission System in California," Ethnohistory 21(4) 974, pp. 291–302.

- Shipek, Florence C. "History of Southern California Mission Indians." Robert F. Heizer, ed. Handbook of North American Indians: California. Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1978.

- Shipek, Florence (1988). Pushed into the Rocks: Southern California Indian Land Tenure 1767–1986. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Sutton, Imre (1964). Land Tenure and Changing Occupance on Indian Reservations in Southern California. Ph.D. dissertation in Geography, UCLA.

- Sutton, Imre (1967). "Private Property in Land Among Reservation Indians in Southern California," Yearbook, Assn of Pacific Coast Geographers, 29:69–89.

- Valley, David J. (2003). Jackpot Trail: Indian Gaming in Southern California San Diego: Sunbelt Publications.

- White, Raymond C. (1963). "A Reconstruction of Luiseño Social Organization." University of California, Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology. Volume 49, no. 2.

External links

- Indians of the California Missions: Territories, Affiliations and Descendants at the California Frontier Project

- Handbook of the Indians of California in the Claremont Colleges Digital Library

- Matrimonial Investigation Records of the San Gabriel Mission in the Claremont Colleges Digital Library

- "Two Myths of the Mission Indians of California" by Alfred L. Kroeber (1906)

- "Mythology of the Mission Indians" by Constance Goddard DuBois (1906)