Bayou Teche

The Bayou Teche (Louisiana French: Bayou Têche) is a 125-mile-long (201 km)[1] waterway of great cultural significance in south central Louisiana in the United States. Bayou Teche was the Mississippi River's main course when it developed a delta about 2,800 to 4,500 years ago. Through a natural process known as deltaic switching, the river's deposits of silt and sediment cause the Mississippi to change its course every thousand years or so.

History

The Teche begins in Port Barre where it draws water from Bayou Courtableau and then flows southward to meet the Lower Atchafalaya River at Patterson. During the time of the Acadian migration to what was then known as the Attakapas region, the Teche was the primary means of transportation.

During the American Civil War, there were two gunboat engagements on Bayou Teche. The first of these occurred on November 3–5, 1862. Four Federal gunboats, USS Kinsman, USS Calhoun, USS Estrella, and USS Diana, with twenty-seven guns came up the Teche despite weak obstructions placed in the bayou by Confederate General Alfred Mouton. The gunboats engaged the Confederate gunboat CSS J. A. Cotton near Cornay's Bridge in an exchange that lasted for an hour and a half. The J. A. Cotton was a wooden steamboat modified with a casemate of timber and cotton bales with a small amount of railroad iron tacked onto the side.[2] Though struck several times, the Cotton escaped real damage. In the next two days, two other duels occurred, and each time the Cotton prevailed. That night the Northern ships captured A. B. Seaer, a small Steamer of the Confederate Navy used as a dispatch boat. Five days later, Kinsman and A. B. Seger captured and burned steamers Osprey and J. P. Smith in Bayou Cheval, Louisiana.

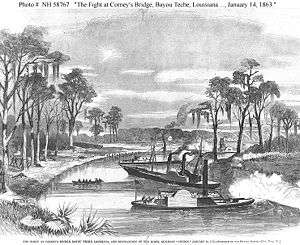

The second engagement occurred on 14 January 1863. Union general Godfrey Weitzel learned that the J. A. Cotton was planning an attack on Weitzel's forces at Berwick Bay, Louisiana. Once again Kinsman, Calhoun, Estrella and Diana steamed into the Bayou, followed by Union transports. The bayou had been obstructed with debris. The Union gunboats and land-based units engaged the J. A. Cotton and Confederate infantry in rifle pits. During the battle Kinsman hit a mine and unshipped her rudder; the J. A. Cotton was badly damaged, and her crew set her on fire during the night to prevent capture.[3] The Union, however, was unable to hold the Teche, necessitating two more invasions of the Teche country in 1863 and 1864.

The Union eventually pacified the area of Bayou Teche and the Atchafalaya River. Historian John D. Winters reports: "Federal troops collected horses, mules, and sugar in large quantities. Planters who remained began taking the oath [to the U.S. government] and were allowed to make contracts with the Negroes to finish their sugar crops."[4]

After the levees were built along the Atachafalaya River in the 1930s, the Teche and the rice farms located along the bayou suffered a drastic reduction in fresh water. Between 1976 and 1982, the United States Army Corps of Engineers built a pumping station at Krotz Springs to pump water from the Atchafalaya River into Bayou Courtableau.

The etymology of the name "Teche" is uncertain. One hypothesis is that it comes from "tenche", a Chitimacha Indian word meaning "snake", related to the bayou's twists and turns resembling a snake's movement. The Chitimacha tell an ancient story of how the snake attacked their villages, and it took many warriors many years to kill it. Where the huge carcass lay and decomposed, the depression it left behind filled with water to become the bayou.[5] Alternatively, George R. Stewart asserts that it is, "probably a French rendering of Deutsch, the name by which the German colonists of the area would have named their stream. Cf. Allemand ['German']."[6]

The southern author Harnett Kane in The Bayous of Louisiana (1943) titles his chapter on the Teche "The Opulent Teche" and terms the Teche "the most handsomely endowed of the bayous."[7]

The sugar plantation Lagonda was established on Bayou Teche by Lewis Strong Clarke, who was also involved in Republican politics in the late 19th century.[8]

Towns on Bayou Teche

Towns along the Teche include:

- St. Landry Parish, Louisiana

- St. Martin Parish, Louisiana

- Iberia Parish, Louisiana

- Loreauville, Louisiana

- Morbihan, Louisiana

- New Iberia, Louisiana

- Jeanerette, Louisiana

- St. Mary Parish, Louisiana

See also

- Bayou Teche National Wildlife Refuge

- Louisiana Swamps

- Bo Ackal, namesake of bridge over Bayou Teche on Lewis Street in Iberia Parish

- Bret Allain, sugar cane farmer and state senator from St. Mary Parish was reared on Bayou Teche.

References

- U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map Archived 2012-03-29 at the Wayback Machine, accessed June 20, 2011

- Campbell, R. Thomas (2008). Voices of the Confederate Navy: Articles, Letters, Reports, and Reminiscences. McFarland. p. 139. ISBN 9780786431489. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- Rains, Gabriel J.; Michie, Peter S. (2011). Confederate Torpedoes: Two Illustrated 19th Century Works with New Appendices and Photographs. McFarland. p. 142. ISBN 9780786485451. Retrieved 27 July 2017.

- John D. Winters, The Civil War in Louisiana, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1963, ISBN 0-8071-0834-0, p. 162-163

- Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism. "Bayou Teche Historical Marker".

- George R. Stewart American Place-names (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970), p. 475.

- Horace Reynolds (October 31, 1943). "Southern Backwaters; The Bayous of Louisiana. By Harnett T. Kane. Illustrated with drawings by Tilden Landry and photographs. 340 pp. New York: William Morrow & Co. $3.50". The New York Times. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- "Clarke, Lewis Strong". A Dictionary of Louisiana Biography. Louisiana Historical Association. Archived from the original on February 25, 2012. Retrieved December 21, 2010.