Indigenous peoples of California

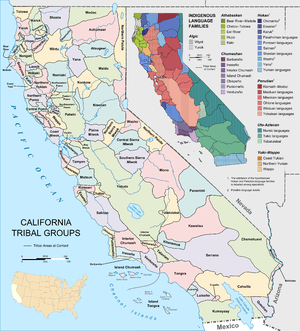

The indigenous peoples of California (known as Native Californians) are the indigenous inhabitants who have lived or currently live in the geographic area within the current boundaries of California before and after the arrival of Europeans. With over forty groups seeking to be federally recognized tribes, California has the second largest Native American population in the United States.[1] The California cultural area does not conform exactly to the state of California's boundaries. Many tribes on the eastern border with Nevada are classified as Great Basin tribes,[2] and some tribes on the Oregon border are classified as Plateau tribes. Tribes in Baja California who do not cross into California are classified as indigenous peoples of Mexico.[3]

.jpg)

_by_Grace_Hudson.jpg)

List of peoples

- Achomawi, Achumawi, Pit River tribe, northeastern California[4]

- Atsugewi, northeastern California[4]

- Chumash, coastal southern California[4]

- "Barbareño", Coast Central Chumash

- "Cruzeño, Isleño", Island Chumash

- "Emigdiano", Tecuya, Interior Central Chumash

- "Interior", Cuyama, Interior Northwestern Chumash

- "Inezeño", "Ineseño", Samala, Inland Central Chumash

- "Obispeño", Yak-tityu-tityu-yak-tilhini, Northern Chumash

- "Purisimeño", Kagismuwas, Northern Chumash

- "Ventureño", Alliklik – Castac, Southern Chumash

- Chilula, northwestern California[4]

- Chimariko, extinct, northwestern California[5]

- Kuneste, "Eel River Athapaskan peoples"

- Esselen, west-central California[4]

- Hupa, northwestern California[4]

- Karok, northwestern California[4]

- Kato, Cahto, northwestern California[4]

- Konkow, northern-central California[4]

- Kumeyaay, Diegueño, Kumiai

- La Jolla Complex, southern California, c. 6050–1000 BCE

- Maidu, northeastern California[4]

- Miwok, Me-wuk, central California[4]

- Bay Miwok, west-central California[4]

- Coast Miwok, west-central California[4]

- Lake Miwok, west-central California[4]

- Valley and Sierra Miwok

- Monache, Western Mono, central California[4]

- Nisenan, eastern-central California[4]

- Nomlaki, northwestern California[4]

- Ohlone, Costanoan, west-central California[4]

- Patwin, central California[4]

- Suisun, Southern Patwin, central California

- Pauma Complex, southern California, c. 6050–1000 BCE

- Pomo, northwestern and central-western California[4]

- Te'po'ta'ahl, ("Salinan"), coastal central California[4]

- Shasta northwestern California[4]

- Konomihu, northwestern California

- Okwanuchu, northwestern California

- Tolowa, northwestern California[4]

- Takic

- Acjachemem, ("Juaneño"), Takic, southwestern California

- Iívil̃uqaletem, Iviatim, ("Cahuilla"), Takic southern California[4]

- Kitanemuk, ("Tejon") Takic, south-central California[4]

- Kuupangaxwichem, ("Cupeño"), southern California[4]

- Payómkawichum, ("Luiseño"), Takic, southwestern California[4]

- Tataviam, Allilik Takic ("Fernandeño"), southern California[4]

- Tongva, ("Gabrieleño"), ("Fernandeño"), ("Nicoleño"), "San Clemente tribe" Takic, coastal southern California[4]

- Yuhaviatam Morongo, Vanyume Mohineyam ("Serrano"), southern California[4]

- Tubatulabal, south-central California[4]

- Bankalachi, Toloim, south-central California

- Pahkanapil, south-central California

- Palagewan, south-central California

- Wappo, north-central California[4]

- Whilkut, northwestern California[4]

- Wintu, northwestern California[4]

- Wiyot, northwestern California[4]

- Yana, northern-central California[4]

- Yokuts, central and southern California[4]

- Chukchansi, Foothill Yokuts, central California[4]

- Northern Valley Yokuts, central California[4]

- Tachi tribe, Southern Valley Yokuts, south-central California[4]

- Yuki, Ukomno'm, northwestern California[4]

- Yurok, northwestern California[4]

Languages

Before European contact, native Californians spoke over 300 dialects of approximately 100 distinct languages. The large number of languages has been related to the ecological diversity of California,[10] and to a sociopolitical organization into small tribelets (usually 100 individuals or fewer) with a shared "ideology that defined language boundaries as unalterable natural features inherent in the land".[11]

"The majority of California Indian languages belong either to highly localized language families with two or three members (e.g. Yukian, Maiduan) or are language isolates (e.g. Karuk, Esselen)."[12] Of the remainder, most are Uto-Aztecan or Athapaskan languages. Larger groupings have been proposed. The Hokan superstock has the greatest time depth and has been most difficult to demonstrate; Penutian is somewhat less controversial.

There is evidence suggestive that speakers of the Chumashan languages and Yukian languages, and possibly languages of southern Baja California such as Waikuri, were in California prior to the arrival of Penutian languages from the north and Uto-Aztecan from the east, perhaps predating even the Hokan languages.[13] Wiyot and Yurok are distantly related to Algonquian languages in a larger grouping called Algic. The several Athapaskan languages are relatively recent arrivals, having arrived about 2000 years ago.

History

Precontact

Evidence of human occupation of California dates from at least 19,000 years ago.[14] Prior to European contact, California Indians had 500 distinct sub-tribes or groups, each consisting of 50 to 500 individual members.[3] The size of California tribes today are small compared to tribes in other regions of the United States. Prior to contact with Europeans, the California region contained the highest Native American population density north of what is now Mexico.[3] Because of the temperate climate and easy access to food sources, approximately one-third of all Native Americans in the United States were living in the area of California.[15]

Early Native Californians were hunter-gatherers, with seed collection becoming widespread around 9,000 BC.[3] Due to the local abundance of food, tribes never developed agriculture or tilled the soil. Two early southern California cultural traditions include the La Jolla Complex and the Pauma Complex, both dating from c. 6050–1000 BCE. From 3000 to 2000 BCE, regional diversity developed, with the peoples making fine-tuned adaptations to local environments. Traits recognizable to historic tribes were developed by approximately 500 BCE.[16]

The indigenous people practiced various forms of sophisticated forest gardening in the forests, grasslands, mixed woodlands, and wetlands to ensure availability of food and medicine plants. They controlled fire on a regional scale to create a low-intensity fire ecology; this prevented larger, catastrophic fires and sustained a low-density "wild" agriculture in loose rotation.[17][18][19][20] By burning underbrush and grass, the natives revitalized patches of land and provided fresh shoots to attract food animals. A form of fire-stick farming was used to clear areas of old growth to encourage new in a repeated cycle; a permaculture.[19]

Contact with Europeans

Different tribes encountered non-native European explorers and settlers at widely different times. The southern and central coastal tribes encountered European explorers in the mid-16th century. Tribes such as the Quechan or Yuman Indians in present-day southeast California and southwest Arizona first encountered Spanish explorers in the 1760s and 1770s. Tribes on the coast of northwest California, like the Miwok, Yurok, and Yokut, had contact with Russian explorers and seafarers in the late 18th century.[21] In remote interior regions, some tribes did not meet non-natives until the mid-19th century.[22]

Mission era

The Spanish began their long-term occupation in California in 1769 with the founding of Mission San Diego de Alcalá in San Diego. The Spanish built 20 additional missions in California.[23][24] Their introduction of European invasive plant species and non-native diseases resulted in havoc and high fatalities for the Native Californian tribes.

19th century

The population of Native California was reduced by 90% during the 19th century—from more than 200,000 in the early 19th century to approximately 15,000 at the end of the century, mostly due to disease.[16] Epidemics swept through California Indian Country, such as the 1833 malaria epidemic.[22]

Early to mid 19th Century, coastal tribes of northwest California had multiple contacts with Russian explorers due to Russian colonization of the Americas. At that time period, Russian exploration of California and contacts with local population were usually associated with the activity of the Russian-American Company. A Russian explorer, Baron Ferdinand von Wrangell, visited California in 1818, 1833, and 1835.[25] Looking for a potential site for a new outpost of the company in California in place of Fort Ross, Wrangell's expedition encountered the Indians north of San Francisco Bay and visited their village. In his notes Wrangell remarked that local women, used to physical labor, seemed to be of stronger constitution than men, whose main activity was hunting. Local provision consisted primarily of fish and products made of seeds and grains: usually ground acorns and wild rye. Wrangell surmised his impressions of the California Indians as a people with a natural propensity for independence, inventive spirit, and a unique sense of the beautiful.[26]

Another notable Russian expedition to California was the 13 months long visit of the scientist Ilya Voznesensky in 1840–1841. Voznesensky's goal was to gather some ethnographic, biological, and geological materials for the collection of the Imperial Academy of Sciences. He described the locals that he met on his trip to Cape Mendocino as "the untamed Indian tribes of New Albion, who roam like animals and, protected by impenetrable vegetation, keep from being enslaved by the Spanish".[27]

In 1834 Mexico secularized the Church's missions and confiscated their properties. But the new government did not return their lands to tribes but made land grants to settlers of at least partial European ancestry. Many landless Indians found wage labor on ranches. Following the United States victory in the Mexican–American War, it took control of California in 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Its administrators worked to honor Mexican land grant title but did not honor aboriginal land title.[22]

California Gold Rush (1848–1855)

.png)

Conflicts and genocide

Most of inland California including California deserts and the Central Valley was in possession of the local tribes until the acquisition of Alta California by the United States. As the wave of immigrants from the United States started to settle inland California during the Gold Rush, conflicts between the Native Californians and the immigrants started to arise. The series of massacres, battles, and wars between the United States and the indigenous peoples of California lasting from 1850 to 1880 is referred to as the California Indian Wars.

After guns and horses were introduced to the indigenous peoples of California in the beginning of the 19th century, the tensions between the neighboring tribes started to increase. In combination with the mass migration, that caused dramatic changes. When in 1846 the Applegate Trail cut through the Modoc territory, the migrants and their livestock damaged the ecosystem that the locals were dependent on.[28]

Some anthropologists insist that the indigenous resistance is often used to camouflage genocide in colonial history. For instance, the final stage of the Modoc Campaign was triggered when Modoc men led by Kintpuash (AKA Captain Jack) murdered General Canby at the peace tent in 1873. However, it's not widely known that between 1851 and 1872 the Modoc population decreased by 75 to 88% as a result of seven anti-Modoc campaigns started by the whites.[29] There is evidence that the first massacre of the Modocs by the white men possibly happened as early as 1840. According to the story told by a chief of the Achumawi tribe (neighboring to Modocs), a group of trappers from the north stopped by the Tule lake around the year 1840 and invited the Modocs to a feast. As they sat down to eat, the cannon was fired and many Indians were killed. The father of Captain Jack was among the survivors of that attack. Since then the Modocs resisted the intruders notoriously.[30]

See also: California Genocide

20th century

During the end of the 19th Century and the beginning of the 20th century, the government attempted to force the indigenous peoples to break the ties with their native culture and tribalism and assimilate with the white society. In California, the federal government established such forms of education as the reservation day schools and American Indian boarding schools. Some public schools would allow Indians to attend as well. Poor ventilation and nutrition (due to limited funding), and diseases were typical problems at schools for American Indians. In addition to that, most parents disagreed with the idea of their children being raised as whites: at boarding schools, the students were forced to wear European style clothes and haircuts, were given European names, and were strictly forbidden to speak indigenous languages. The Native American community recognized the American Indian boarding schools to have oppressed their native culture and demanded the right for their children to access public schools. In 1935 the restrictions that forbid the Native Americans from attending public schools were officially removed.[31]

Since the 1920s, various Indian activist groups were demanding that the federal government fulfil the conditions of the 18 treaties of 1851–1852 that were never ratified and apparently, were classified.[32] In 1944 and in 1946 the native peoples brought claims for reimbursements asking for compensations for the lands affected by treaties and Mexican land grants. They won $17.5 million and $46 million, respectively.[31]

Throughout the 20th century, the population of indigenous peoples of California gradually rose.

21st century

California has the largest population of Native Americans out of any state in the United States, with 723,000 identifying an "American Indian or Alaska Native" tribe as a component of their race (14% of the nation-wide total). This population grew by 15% between 2000 and 2010, much less than the nation-wide growth rate of 27%, but higher than the population growth rate for all races, which was about 10% in California over that decade. Over 50,000 indigenous people live in Los Angeles alone.[33][34]

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, there are currently over one hundred federally recognized native groups or tribes in California including those that spread to several states.[35] Federal recognition officially grants the Indian tribes access to services and funding from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and Federal and State funding for Tribal TANF/CalWORKs programs.

Material culture

.jpg)

Basket making was an important part of Native American Californian culture.[36] Baskets were both beautiful and functional, with a wide variety of shapes and sizes based on their function, and of different patterns. Baskets were generally made by women.

Foods

Acorns are a primary traditional food throughout much of California. Corn was very important as well. Different tribes' diets included fish, shellfish, insects, deer, elk, antelope, and plants such as buckeye, sage seed, and yampah (Perideridia gairdneri).[3]

Society and culture

Many tribes in Central California and Northern California practised the Kuksu religion, especially the Nisenan, Maidu, Pomo and Patwin tribes.[37] The practice of Kuksu included elaborate narrative ceremonial dances and specific regalia. A male secret society met in underground dance rooms and danced in disguises at the public dances.[38]

In Southern California the Toloache religion was dominant among tribes such as the Luiseño and Diegueño.[39] Ceremonies were performed after consuming a hallucinogenic drink made of the jimsonweed or Toloache plant (Datura meteloides), which put devotees in a trance and gave them access to supernatural knowledge.

Native American culture in California was also noted for its rock art, especially among the Chumash of southern California.[40] The rock art, or pictographs were brightly colored paintings of humans, animals and abstract designs, and were thought to have had religious significance.

See also

References

- "American Indians". SDSU Library and Information Access. Archived from the original on 2010-06-13 – via Wayback Machine.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Historic Tribes of the Great Basin –Great Basin National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". Nps.gov. Retrieved 2018-02-04.

- Pritzker 112

- Heizer ix

- Heizer 205–07

- Heizer 190

- Heizer 593

- Heizer 769

- Heizer 249

- Codding, B. F.; Jones, T. L. (2013). "Environmental productivity predicts migration, demographic, and linguistic patterns in prehistoric California". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (36): 14569. doi:10.1073/pnas.1302008110. PMC 3767520. PMID 23959871.

- Golla (2011:1)

- Golla (2011:8).

- Golla (2011)

- Klein, Barry T. Reference Encyclopedia of the American Indian. 7th ed. West Nyack, NY: Todd Publications, 1995

- Starr, Kevin. California: A History, New York, Modern Library (2005), p. 13

- Pritzker 113

- Neil G. Sugihara; Jan W. Van Wagtendonk; Kevin E. Shaffer; Joann Fites-Kaufman; Andrea E. Thode, eds. (2006). "17". Fire in California's Ecosystems. University of California Press. pp. 417. ISBN 978-0-520-24605-8.

- Blackburn, Thomas C. and Kat Anderson, ed. (1993). Before the Wilderness: Environmental Management by Native Californians. Menlo Park, California: Ballena Press. ISBN 0879191260.

- Cunningham, Laura (2010). State of Change: Forgotten Landscapes of California. Berkeley, California: Heyday. pp. 135, 173–202. ISBN 1597141364.

- Anderson, M. Kat (2006). Tending the Wild: Native American Knowledge And the Management of California's Natural Resources. University of California Press. ISBN 0520248511.

- "Alaska and California in the Eighteenth Century – Jonathan's Guide to US History". Jonathan-guide.neocities.org. Retrieved 2018-02-02.

- Pritzker 114

- Castillo, Edward D. "California Indian History." California Native American Heritage Association. (retrieved 10 Sept 2010)

- Herrera, Allison (December 13, 2017). "In California, Salinan Indians Are Trying To Reclaim Their Culture And Land". Npr.org. All Things Considered. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- Hudson, Travis, et al., Treasures From Native California: The Legacy of Russian Exploration, Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press, Inc., 2014, p. 10

- Hudson, Travis, et al., Treasures From Native California: The Legacy of Russian Exploration, Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press, Inc., 2014, p. 11

- Hudson, Travis, et al., Treasures From Native California: The Legacy of Russian Exploration, Walnut Creek, California: Left Coast Press, Inc., 2014, p. 12

- Woolford, Andrew, Benvenuto, Jeff, Laban Hilton, Alexander, Colonial Genocide in Indigenous North America, Durham, Duke University Press, 2014, p. 96

- Woolford, Andrew, Benvenuto, Jeff, Laban Hilton, Alexander, Colonial Genocide in Indigenous North America, Durham, Duke University Press, 2014, p. 95

- Woolford, Andrew, Benvenuto, Jeff, Laban Hilton, Alexander, Colonial Genocide in Indigenous North America, Durham, Duke University Press, 2014, pp. 95–96

- "Indians of California – American Period". Cabrillo.edu.

- "The Treaties Secret With California's Indians" (PDF). Archives.gov. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- Tina Norris; Paula L. Vines; Elizabeth M. Hoeffel. The American Indian an Alaska Native Population: 2010 (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2018-03-04.

- "Top 5 Cities With The Most Native Americans". Indiancountrymedianetwork.com. Indian Country Media Network. Archived from the original on 2018-02-05. Retrieved 2018-02-04.

- Legislatures, National Conference of State. "List of Federal and State Recognized Tribes". Ncsl.org. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- "Native Americans: Pre-Columbian California to 18th Century". Calisphere.org.

- "Kuksu Cult". 11 October 2006. Archived from the original on 11 October 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- Kroeber, Alfred L. The Religion of the Indians of California, 1907.

- "California Indian - people". Britannica.com.

- Penney, David W. (2004), North American Indian Art, London: Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-20377-6

- Works cited

- Golla, Victor (2011). California Indian Languages. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26667-4.

- Heizer, Robert F., volume editor (1978). Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 8: California. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 978-0-16-004574-5.

- Hinton, Leanne (1994). Flutes of Fire: Essays on California Indian Languages. Berkeley: Heyday Books. ISBN 0-930588-62-2.

- Hurtado, Albert L. (1988). Indian Survival on the California Frontier. Yale Western Americana series. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300041470.

- Lightfoot, Kent G. and Otis Parrish (2009). California Indians and Their Environment: An Introduction. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24471-9.

- Pritzker, Barry M. (2000). A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Native Americans of California. |

- "Information About California Tribes" Northern California Indian Development Council

- Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival

- California Indian Museum and Cultural Center, Santa Rosa

- "California Indian History," California Native American Heritage Association

- "California Indians," SDSU Library and Information Access

- Bibliographies of Northern and Central California Indians

- "A Glossary of Proper Names in California Prehistory", Society for California Archaeology

- 27th Annual California Indian Conference, California State University San Marcos, Oct. 5–6, 2012