Yustaga

The Yustaga were a Timucua people of what is now northwestern Florida during the 16th and 17th centuries. The westernmost Timucua group, they lived between the Aucilla and Suwannee Rivers in the Florida Panhandle, just east of the Apalachee people. A dominant force in regional tribal politics, they may have been organized as a loose regional chiefdom consisting of up to eight smaller local chiefdoms.[1]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Extinct as group | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Northwest Florida between the Aucilla and Suwannee Rivers | |

| Languages | |

| Timucuan language, possibly the Potano dialect | |

| Religion | |

| Native | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Timucua (particularly Northern Utina) |

The Yustaga were closely associated with the Northern Utina people living on the other side of the Suwannee River, though they appear to have spoken a different dialect of the Timucua language, perhaps Potano. The Yustaga were among the first Timucua to encounter Europeans, as their location near the Apalachee ensured that several explorers passed through their territory looking for that group. After decades of resistance they were brought into the Spanish mission system in the 1620s. Like all Timucua groups, they experienced significant demographic decline in the period of European contact, especially following raids by English-allied Indians from the north. Surviving Yustaga eventually moved closer to the Spanish capital of St. Augustine and mingled with other missionized Indians, losing their independent identity.

Area

The westernmost of all Timucua groups, the Yustaga's territory extended into the Florida Panhandle and southwestern Georgia. They lived in the western Suwannee River valley, roughly between the Aucilla and Suwannee Rivers (present-day Madison and Taylor Counties).[2][3] On the east side of the Suwannee, inhabiting a territory spanning roughly to the St. Johns River in the east and the Santa Fe River in the south, lived another Timucua people, the Northern Utina. The Northern Utina were closely associated with the Yustaga, but spoke a different dialect, known as Timucua proper.[2] To the east of the Yustaga was a region known as the Apalachee Province, inhabited by the Apalachee and other peoples.[4]

Prehistorical era

The Yustaga region had been inhabited for thousands of years. During the first millennium AD its inhabitants participated in the Weedon Island culture, which spread across much of western Florida and beyond. From about 900 a derivative culture emerged among the peoples of the Suwannee River Valley, the groups later designated as the Yustaga and Northern Utina. This culture, known as the Suwannee Valley culture, is particularly distinguished by its ceramics, and was still extant at the time of European contact. As a Weedon Island derivative, it is closely related to the Alachua culture of the Potano, a Timucua group of what is now Alachua County.[5]

The dialect spoken by the Yustaga is unclear, as the tribe had not been missionized at the time Father Francisco Pareja, the principal source for the Timucua language and its dialects, undertook his linguistic work between 1612 and 1627.[6] However, a 1651 letter written by the Yustaga chief Manuel to the Spanish crown survives in the Spanish archives. The language of the letter is very similar to that in sources from the Potano tribe of present-day Alachua County, leading scholars such as the linguist Julian Granberry to conclude the Yustaga spoke the Potano dialect noted by Pareja.[7]

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Yustaga, like the Northern Utina, lived in distinct groups of villages, probably representing small-scale local chiefdoms.[8] Around eight such community groups were known in historical times.[1] Anthropologist John Worth suggests these might have been organized into a loose regional chiefdom that was continuous from at least the early period of European contact.[8] In this arrangement, the head of the most important town, Cotocochuni or Potohiriba, would have been paramount chief over all others. Possible evidence for this lies in the fact that later Spanish lists of Yustaga chiefs consistently name them in order of the prominence of their towns, with Potohiriba invariably first. Additionally, the Spanish built a mission at Potohiriba before any other Yustaga town, despite its comparatively remote location, suggesting it was already a center of considerable regional importance.[9]

Even still, Worth notes the regional Yustaga chiefdom would have been much less integrated than certain eastern Timucua chiefdoms such as the Saturiwa and (eastern) Utina. Ceramic dating may vary from community to community, suggesting a level of regional disunity, and no large-scale monuments such as platform mounds, often signs of integrated regional chiefdoms, have been discovered in Yustaga territory.[10]

European contact

The Yustaga appear to have encountered the expedition of Pánfilo de Narváez when it came through the area in 1528. Expedition survivor Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca records a meeting with a great chief named Dulchanchellin, who lived east of Apalachee and may have been the predecessor to the later Yustaga paramount chiefs.[11][12]

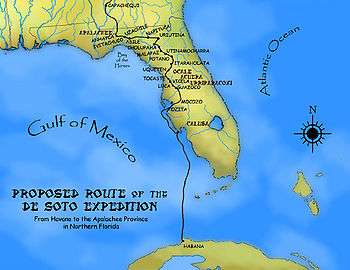

However, the name "Yustaga" first appears in the chronicles of Hernando de Soto's 1539 expedition, which describe it as the region immediately east of Apalachee.[4] In de Soto's time the chiefdom was ruled by a chief named Uzachile, who was allied with (and possibly related to) the paramount chief on the other side of the Suwannee, Aguacaleycuen, whose domain corresponds to the later Northern Utina.[4] Uzachile may have been paramount over the various chiefdoms of more or less equal status on both sides of the river. They may have been in a defensive alliance against the Apalachees, the Utina (of the St. Johns River valley) and the Potano.[13]

Upon reaching Aguacaleycuen's village, De Soto captured the chief, as was his usual practice, intending to release him upon his party's safe arrival at Uzachile's village. Thereafter some chiefs approached de Soto and offered to take him to Uzachile, whom they said sought an alliance against the Apalachee. Instead, they led the Spanish into an ambush. De Soto ultimately prevailed and subsequently executed Aguacaleycuen and other hostages, but by the time he got into Yustaga, the villages had already been evacuated.[4] De Soto and his men reached the town of Uzachile on 25 September, and stayed there for four days. One chronicler stated that there were 200 houses in the town, with plenty of maize, beans and pumpkins.[14]

Sources from the French Huguenot settlement of Fort Caroline, established in 1564, record a chief named "Houstaqua", whose name is probably a variant of Yustaga.[15] The French understood that Houstaqua and his neighbor, Onatheaqua (probably a chief of the Northern Utina), lived to the east of the Apalachee. However, they thought they lived near gold-bearing mountains (the Appalachian Mountains, which the Europeans thought extended into the Apalachee Province). French soldiers visited the Yustaga on two occasions, exchanging gifts with the chief and sojourning among his people for several months. The French reports credited Houstaqua with 3000 to 4000 warriors.[16][17]

Mission era

The Spanish, who displaced the French from Florida in 1565, established a system of missions to convert the natives to Christianity. Unlike most Timucua groups, who generally requested missionaries from the Spanish of their own volition, the Yustaga actively resisted Spanish missionary efforts.[18] Spanish records indicate that the paramount chief of the Yustaga consistently refused to allow missionaries to even enter his territory until the 1620s, over twenty years after missionization had begun among the Northern Utina and other interior groups.[19]

Around 1623 the chief of Cotocochuni, probably the main village of the Yustaga regional chiefdom, finally consented to two friars entering his territory, though he forbade his subjects from getting baptized or providing the missionaries with food.[19] Eventually, however, both the chief and his daughter converted to Christianity, and the conversion of the Yustaga proceeded quickly thereafter. Mission San Pedro de Potohiriba was established at Cotocochuni, and over time missions were built at the main villages of the other local chiefdoms.[20] This project, which established Yustaga as a province of the Spanish mission system, was the most significant of its kind in the early 17th century.[19]

Having much less frequent contact with the Europeans and the diseases they introduced, the Yustaga maintained stable population levels later than any other Timucua group. At the start of the mission period the Yustaga Province was by far the most populous, having an estimated 12,000 inhabitants, compared to only 7,500 in the Timucua Province, which at that time included the Northern Utina as well as the Potano and other groups.[21]

The Yustaga played what is often called the "Apalachee ball game." A missionary wrote an account of the Yustaga ball game in 1630. He indicated that the game was played with 50 or even 100 players on a team, and that large crowds would gather to watch the games. While the Apalachee yielded to missionary pressure and stopped playing the game in 1677, the Yustaga refused to do so, insisting that their version of the game did not have the moral problems of the Apalachee version. The game continued to be played by the Yustaga into the 1680s.[22]

The Western Timucua groups, the Potano, Northern Utina and Yustaga, rebelled against Spanish authority in 1656. Lúcas Menéndez, chief of San Martín de Ayacutu, and paramount chief of the Northern Utina, and Diego, chief of Potohiriba, and most powerful of the Yustaga chiefs, led the revolt. Potohiriba was the principal meeting place for the rebels. The rebels killed several Spaniards, a Mexican and some African slaves, but no missionaries. The chiefs of Machaba and Potohiriba were among the rebel leaders captured by the Spanish, and were executed for their roles in the rebellion.[23]

Four missions are known to have been still in use in 1688: Mission San Pedro y San Pablo de Potohiriba, Santa Elena de Machaba, San Miguel de Asile and San Matheo de Tolapatafi (San Miguel de Asile may have been an Apalachee mission). There were 330 families living at the four missions in 1689. Raids by the English of the Province of Carolina and their native allies in 1704 and the years following destroyed the missions in Yustaga.[24]

Notes

- Worth vol. II, p. 5.

- Granberry, p. 3.

- Milanich 1999, p. 55.

- Worth vol. I, p. 31.

- Worth vol. I, pp. 28–29.

- Milanich 1999, p. 44.

- Granberry, pp. xvi–xvii.

- Worth vol. I, p. 96.

- Worth vol. I, pp. 100–102.

- Worth vol. I, pp. 29–30.

- Worth vol. I, pp. 30.

- Milanich 1999, pp. 74–75.

- Milanich & Hudson, pp. 177-179

- Milanich & Hudson, p. 160, 164, 179.

- Worth vol. I, p. 32.

- Milanich 1999, p. 87.

- Milanich & Hudson, pp. 184-185

- Worth, pp. 40–41.

- Worth vol. I, pp. 71–72.

- Worth, p. 74.

- Worth vol. II, p. 6.

- Hann, pp. 108-110

- Hann, pp. 200, 203, 205-208, 217-218, 220

- Milanich & Hudson, p. 186.

References

- Hann, John H. (1996). A History of the Timucua Indians and Missions. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1424-7.

- Laudonnière, René; Bennett, Charles E. (Ed.) (2001). Three Voyages. University of Alabama Press.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Milanich, Jerald T.; Hudson, Charles (1993). Hernando de Soto and the Indians of Florida. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1170-1.

- Milanich, Jerald (1999). The Timucua. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0631218645. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- Swanton, John Reed (2003). The Indian tribes of North America. Genealogical Publishing. ISBN 0806317302. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- Worth, John E. (1998). Timucua Chiefdoms of Spanish Florida. Volume 1: Assimilation. University Press of Florida. ISBN 081301574X. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- Worth, John E. (1998). Timucua Chiefdoms of Spanish Florida. Volume 2: Resistance and Destruction. University Press of Florida. ISBN 081301574X. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

Further reading

- Hann, John H. (2003). Indians of Central and South Florida: 1513-1783. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of florida. ISBN 0-8130-2645-8.