Khalistan movement

The Khalistan movement is a Sikh separatist movement seeking to create a homeland for Sikhs by establishing a sovereign state, called Khalistān ('Land of the Khalsa'), in the Punjab region.[1] The proposed state would consist of land that currently forms Punjab, India and Punjab, Pakistan,[lower-roman 1] However this has been refuted by many proponents of Khalistan as they seek to create a Sikh homeland in Indian Punjab, where they form a majority. [2]

Ever since the separatist movement gathered force in the 1980s, Pakistan has sided with the Sikhs, and the territorial ambitions of Khalistan have at times included Chandigarh, sections of the Indian Punjab, including whole North India and some parts of western states of India.[3] Prime Minister of Pakistan Zulfikar Ali Bhutto of Pakistan, according to Jagjit Singh Chohan, had proposed all out help to create Khalistan during his talks with Chohan following the conclusion of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971.[4]

The Khalistan movement was established in the wake of the fall of the British Empire.[5] In 1940, the first explicit call for Khalistan was made in a pamphlet titled "Khalistan".[6][7] With financial and political support of the Sikh diaspora, the movement flourished in the Indian state of Punjab—which has a Sikh-majority population—reaching its zenith in the late 1970s and 1980s when the secessionist movement caused large-scale violence among the local population, including the assassination of PM Indira Gandhi and the bombing of Air India Flight 182 which killed 329 passengers.[8] In the 1990s the insurgency petered out,[9] and the movement failed to reach its objective due to multiple reasons including a heavy police crackdown on separatists, divisions among the Sikhs, and loss of support from the Sikh population.[10]

There is some support within India and the Sikh diaspora, with yearly demonstrations in protest of those killed during Operation Blue Star.[11][12][13] In early 2018, some militant groups were arrested by police in Punjab, India.[10] Chief Minister of Punjab Amarinder Singh claimed that the recent extremism is backed by Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) and "Khalistani sympathisers" in Canada, Italy, and the UK.[14]

Pre-1950s

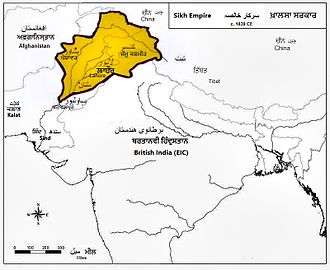

Sikhs have been concentrated in the Punjab region of South Asia.[15] Before its conquest by the British, the region around Punjab had been ruled by the confederacy of Sikh Misls founded by Banda Bahadur. The Misls ruled over the entire Punjab from 1767 to 1799,[16] until their confederacy was unified into the Sikh Empire by Maharajah Ranjit Singh from 1799 to 1849.[17]

At the end of the Second Anglo-Sikh War in 1849, the Sikh Empire dissolved into separate princely states and the British province of Punjab.[18] As a result of the British 'divide and conquer' process, which involved differentiating and designating religions into communal boundaries, many religious nationalist movement emerged among the Hindus, Muslims, and the Sikhs. .[19]

As the British Empire began to dissolve in the 1930s, Sikhs made their first call for a Sikh homeland.[5] When the Lahore Resolution of the Muslim League demanded Punjab be made into a Muslim state, the Akalis viewed it as an attempt to usurp a historically Sikh territory.[20][21] In response, the Sikh party Shiromani Akali Dal argued for a community that was separate from Hindus and Muslims.[22] The Akali Dal imagined Khalistan as a theocratic state led by the Maharaja of Patiala with the aid of a cabinet consisting of the representatives of other units.[23] The country would include parts of present-day Punjab, India, present-day Punjab, Pakistan (including Lahore), and the Simla Hill States.[24]

Partition of India, 1947

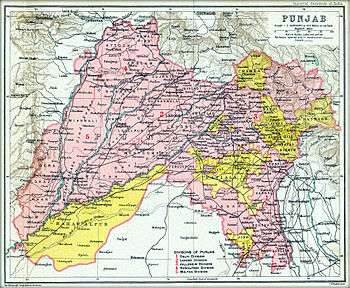

Before the 1947 partition of India, Sikhs were not in majority in any of the districts of pre-partition British Punjab Province other than Ludhiana (where Sikhs formed 41.6% of the population).[25] Rather, districts in the region had a majority of either the Hindus or Muslims depending on its location in the province.

British India was partitioned on a religious basis in 1947, where the Punjab province was divided between India and the newly-created Pakistan. As result, a majority of Sikhs, along with the Hindus, migrated from the Pakistani region to India's Punjab, which included present-day Haryana and Himachal Pradesh. The Sikh population, which had gone as high as 19.8% in some Pakistani districts in 1941, dropped to 0.1% in Pakistan, and rose sharply in the districts assigned to India. However, they would still be a minority in the Punjab province of India, which remained a Hindu-majority province.[26]

Sikh relationship with Punjab (via Oberoi)

Sikh historian Harjot Singh Oberoi argues that, despite the historical linkages between Sikhs and Punjab, territory has never been a major element of Sikh self-definition. He makes the case that the attachment of Punjab with Sikhism is a recent phenomenon, stemming from the 1940s.[27] Historically, Sikhism has been pan-Indian, with the Guru Granth Sahib (the main scripture of Sikhism) drawing from works of saints in both North and South India, while several major seats in Sikhism (e.g. Nankana Sahib in Pakistan, Takht Sri Patna Sahib in Bihar, and Hazur Sahib in Maharashtra) are located outside of Punjab.

Oberoi makes the case that Sikh leaders in the late 1930s and 1940s realized that the dominance of Muslims in Pakistan and of Hindus in India was imminent. To justify a separate Sikh state within the Punjab, Sikh leaders started to mobilize meta-commentaries and signs to argue that Punjab belonged to Sikhs and Sikhs belong to Punjab. This began the territorialization of the Sikh community.[27]

This territorialization of the Sikh community would be formalized in March 1946, when the Sikh political party of Akali Dal passed a resolution proclaiming the natural association of Punjab and the Sikh religious community.[28] Oberoi argues that despite having its beginnings in the early 20th century, Khalistan as a separatist movement was never a major issue until the late 1970s and 1980s when it began to militarize.[29]

1950s to 1970s

There are two distinct narratives about the origins of the calls for a sovereign Khalistan. One refers to the events within India itself, while the other privileges the role of the Sikh diaspora. Both of these narratives vary in the form of governance proposed for this state (e.g. theocracy vs democracy) as well as the proposed name (i.e. Sikhistan vs Khalistan). Even the precise geographical borders of the proposed state differs among them although it was generally imagined to be carved out from one of various historical constructions of the Punjab.[30]

Emergence in India

Established on 14 December 1920, Shiromani Akali Dal was a Sikh political party that sought to form a government in Punjab.[31]

Following the 1947 independence of India, the Punjabi Suba movement, led by the Akali Dal, sought the creation of a province (suba) for Punjabi people. The Akali Dal's maximal position of demands was a sovereign state (i.e. Khalistan), while its minimal position was to have an autonomous state within India.[30] The issues raised during the Punjabi Suba movement were later used as a premise for the creation of a separate Sikh country by proponents of Khalistan.

As the religious-based partition of India led to much bloodshed, the Indian government initially rejected the demand, concerned that creating a Punjabi-majority state would effectively mean yet again creating a state based on religious grounds.[32][33]

However, in September 1966, the Union Government led by Indira Gandhi accepted the demand. On 7 September 1966, the Punjab Reorganisation Act was passed in Parliament, implemented with effect beginning 1 November 1966. Accordingly, Punjab was trifurcated into the state of Punjab and Haryana, with certain areas to Himachal Pradesh. Chandigarh was made a centrally administered Union territory.[34]

Anandpur Resolution

As Punjab and Haryana now shared the capital of Chandigarh, resentment was felt among Sikhs in Punjab.[31] Adding further grievance, a canal system was put in place over the rivers of Ravi, Beas, and Sutlej, which flowed through Punjab, in order for water to also reach Haryana and Rajasthan. As result, Punjab would only receive 23% of the water while the rest would go to the two other states. The fact that the issue would not be revisited brought on additional turmoil to Sikh resentment against Congress.[31]

The Akali Dal was defeated in the 1972 Punjab elections.[35] To regain public appeal, the party put forward the Anandpur Sahib Resolution in 1973 to demand radical devolution of power and further autonomy to Punjab.[36] The resolution document included both religious and political issues, asking for the recognition of Sikhism as a religion separate from Hinduism, as well as the transfer of Chandigarh and certain other areas to Punjab. It also demanded that power be radically devoluted from the Central to state governments.[37]

The document was largely forgotten for some time after its adoption until gaining attention in the following decade. In 1982, the Akali Dal and Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale joined hands to launch the Dharam Yudh Morcha in order to implement the resolution. Thousands of people joined the movement, feeling that it represented a real solution to such demands as larger shares of water for irrigation and the return of Chandigarh to Punjab.[38]

Emergence in the diaspora

According to the 'events outside India' narrative, particularly after 1971, the notion of a sovereign and independent state of Khalistan began to popularize among Sikhs in North America and Europe. One such account is provided by the Khalistan Council which had moorings in West London, where the Khalistan movement is said to have launched in 1970.[30]

Davinder Singh Parmar migrated to London in 1954. According to Parmar, his first pro-Khalistan meeting was attended by less than 20 people and he was labelled as a madman, receiving only one person's support. Parmar continued his efforts despite the lack of a following, eventually raising the Khalistani flag in Birmingham in the 1970s.[39] In 1969, two years after losing the Punjab Assembly elections, Indian politician Jagjit Singh Chohan moved to the United Kingdom to start his campaign for the creation of Khalistan.[40] Apart from Punjab, Himachal, and Haryana, Chohan's proposal of Khalistan also included parts of Rajasthan state.[41]

Parmar and Chohan would meet in 1970 and formally announce the Khalistan movement at a London press conference, though being largely dismissed by the community as fanatical fringe without any support.[39]

Chohan in Pakistan and US

Following the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, Chohan visited Pakistan as a guest of such leaders as Chaudhuri Zahoor Elahi. Visiting Nankana Sahib and several historical gurdwaras in Pakistan, Chohan utilized the opportunity to spread the notion of an independent Sikh state. Widely publicized by Pakistani press, the extensive coverage of his remarks introduced the international community, including those in India, to the demand of Khalistan for the first time. Though lacking public support, the term Khalistan became more and more recognizable.[39] According to Chohan, during a talk with Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto of Pakistan, Bhutto had proposed to make Nankana Sahib the capital of Khalistan.[4]

On 13 October 1971, visiting the United States at the invitation of his supporters in the Sikh diaspora, Chohan placed an advertisement in the New York Times proclaiming an independent Sikh state. Such promotion enabled him to collect millions of dollars from the diaspora,[40] eventually leading to charges in India relating to sedition and other crimes in connection with his separatist activities.

Khalistan National Council

After returning to India in 1977, Chohan travelled to Britain in 1979. There, he would establish the Khalistan National Council,[42] declaring its formation at Anandpur Sahib on 12 April 1980. Chohan designated himself as President of the Council and Balbir Singh Sandhu as its Secretary General.

In May 1980, Chohan travelled to London to announce the formation of Khalistan. A similar announcement was made in Amritsar by Sandhu, who released stamps and currency of Khalistan. Operating from a building termed "Khalistan House", Chohan named a Cabinet and declared himself president of the "Republic of Khalistan," issuing symbolic Khalistan 'passports,' 'postage stamps,' and 'Khalistan dollars.' Moreover, embassies in Britain and other European countries were opened by Chohan.[40] It is reported that, with the support of a wealthy Californian peach magnate, Chohan opened an Ecuadorian bank account to further support his operation.[41] As well as maintaining contacts among various groups in Canada, the US, and Germany, Chohan kept in contact with the Sikh leader Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale who was campaigning for a theocratic Sikh homeland.[40]

The globalized Sikh diaspora invested efforts and resources for Khalistan, but the Khalistan movement remained nearly invisible on the global political scene until the Operation Blue Star of June 1984.[39]

Late 1970s to 1983

Rise of Bhindranwale

The late 1970s and the early 1980s saw the separatist movement begin to militarize, as well as increasing involvement of the Sikh religious preacher Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale in Punjabi politics.[29] Dissatisfaction with economic, social, and political conditions prevailed among some Sikh communities. Bhindranwale, articulating such grievances, including the discrimination against Sikhs and the undermining of Sikh identity,[43] successfully grew as a leader of Sikh militancy.[29]

The significant growth of Bhindranwale's influence did not necessarily come of his own efforts, however,[29] as it would be through his activities with the Congress party that would elevate him to the status of a major leader by the early 1980s.[38]

In the late 1970s, Indira Gandhi's Indian National Congress (INC) party supported Bhindranwale in a bid to split the Sikh vote and weaken the Akali Dal, its chief rival in Punjab.[38] Congress supported the candidates backed by Bhindranwale in the 1978 SGPC elections. INC leader Giani Zail Singh allegedly financed the initial meetings of Dal Khalsa, a separatist organisation that disrupted the December 1978 Ludhiana session of the Akali Dal with provocative anti-Hindu wall-writing.[38][44] In return, Bhindranwale supported INC candidates Gurdial Singh Dhillon and Raghunandan Lal Bhatia in the 1980 election.

Bhindranwale's collaborations with the Congress party later turned out to be a miscalculation, as Bhindranwale's separatist political objectives became popular among the agricultural Jat Sikhs in the region.[29]

Assassination of Lala Jagat Narain (1981)

Lala Jagat Narain, a Hindu, was a leader of the Congress party, owner of the Hind Samachar newspaper group, and a prominent critic of Bhindranwale.

As the 1981 Census of India was recording the mother tongue of Indian citizens, Narain wrote about Hindus living in Punjab reporting 'Hindi' rather than 'Punjabi' as their first language. This infuriated Bhindranwale and his followers.[45] On 9 September 1981, in a politically charged environment, Lala Jagat Narain was assassinated by Sikh militants. The "White Paper on the Punjab Agitation" issued by the Government of India mentions the assassination was due to Narain's criticism of Bhindranwale.[46][47]

On 15 September 1981, Bhindranwale was arrested for his alleged role in Narain's death. Earlier, he had been a suspect in the 24 April 1980 murder of Nirankari leader Gurbachan Singh, who had been killed in retaliation for killings involving conservative Sikhs belonging to the Akhand Kirtani Jatha. Bhindranwale was released in October by the Punjab Government as no evidence was found against him.[48]

Dharam Yudh Morcha (1982)

The Shiromani Akali Dal party was initially opposed to Bhindranwale, even accusing him of being an agent for the INC.[38] However, as Bhindranwale became increasingly influential, the party decided to join forces with him. In August 1982, under the leadership of Harchand Singh Longowal, the Akali Dal collaborated with Bhindranwale to launch the Dharam Yudh Morcha ('Group for the Religious Fight') in order to gain more autonomy for Punjab.

Bhindranwale, however, would hijack the movement, declaring that the Morcha will continue as long as all of the demands in the Anandpur Sahib Resolution were not fulfilled.[49] Indira Gandhi thus considered the Resolution to be a secessionist document and evidence of an attempt to secede from the Union of India. In response, the Akali Dal officially stated that Sikhs were Indians, and that the Resolution did not envisage an autonomous Sikh state (i.e. Khalistan).[50]

The Resolution was made fundamental to Bhindranwale's cause, as the demand for autonomy was phrased in such a way that would have given more authority to Punjab's Sikhs than its Hindus.[49] Thousands of people joined the movement as they felt that it represented a real solution to their demands, such as a larger share of water for irrigation, and the return of Chandigarh to Punjab.[38]

Shortly following the Morcha's launch, Sikh extremists began committing acts of political violence: gunmen open fired on Darbara Singh, Chief Minister of Punjab, while he was attending a funeral;[lower-roman 2] and Dal Khalsa activists hijacked an Indian Airlines flight.[51] By early October, more than 25,000 Akali workers courted arrest (i.e. got arrested on purpose) in Punjab in support of the agitation.[52]

To restart talks with Akali leadership, Gandhi ordered the release of all Akali workers in mid October, sending Swaran Singh as her emissary. Bhindranwale, then regarded as the "single most important Akali leader," announced that nothing less than full implementation of the Anandpur Resolution was acceptable to them. Other Akali leaders agreed to join negotiations, reaching a compromise and settlement with the government's team. The settlement was presented in the parliament, though it would be unilaterally changed in certain parts as per advice from the Chief Ministers of Haryana and Rajasthan.[52]

Delhi Asian Games (1982)

The Akali leaders, having planned to announce a victory for Dharam Yudh Morcha, were outraged by the changes to the agreed-upon settlement. In November 1982, Akali leader Harchand Singh Longowal announced that the party would disrupt the 9th annual Asian Games by sending groups of Akali workers to Delhi to intentionally get arrested. Following negotiations between the Akali Dal and the government failed at the last moment due to disagreements regarding the transfer of areas between Punjab and Haryana.[52]

Knowing that the Games would receive extensive coverage, Akali leaders vowed to overwhelm Delhi with a flood of protestors, aiming to heighten the perception of Sikh "plight" among the international audience.[52] A week before the Games, Bhajan Lal, Chief Minister of Haryana and member of the INC party, responded by sealing the Delhi-Punjab border,[52] and ordering all Sikh visitors travelling from to Delhi from Punjab to be frisked.[53] While such measures were seen as discriminatory and humiliating by Sikhs, they proved effective as Akali Dal could only organize small and scattered protests in Delhi. Consequently, many Sikhs who did not initially support Akalis and Bhindranwale began sympathizing with the Akali Morcha.[52]

Following the conclusion of the Games, Longowal organised a convention of Sikh veterans at the Darbar Sahib. It was attended by a large number of Sikh ex-servicemen, including retd. Major General Shabeg Singh who subsequently became Bhindranwale's military advisor.[52]

1984

Increasing militant activity

Widespread murders by followers of Bhindranwale occurred in 1980s' Punjab. Armed Khalistani militants of this period described themselves as kharku,[54] most likely meaning 'noise maker,' from the Punjabi kharaka ('noise') in reference to their strident activity. In the period between 4 August 1982 and 3 June 1984, more than 1200 violent incidents took place, resulting in the death of 410 people and the injury of 1180.

On its own, the year 1984 (from 1 January to 3 June) saw 775 violent incidents, resulting in 298 people killed and 525 injured.[55] One such murder was that of DIG Avtar Singh Atwal, killed on 25 April 1983 at the gate of the Darbar Sahib,[56] whose corpse would remain at the place of death for 2 hours as even police officers were afraid to touch the body without Bhindranwale's permission. This showed the power and influence that Bhindranwale had over the region.[57][58]

Though it was common knowledge that those responsible for such bombings and murders were taking shelter in gurdwaras, the INC Government of India declared that it could not enter these places of worship, for the fear of hurting Sikh sentiments.[38] Even as detailed reports on the open shipping of arms-laden trucks were sent to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, the Government would choose not to take action.[38] Finally, following the murder of six Hindu bus passengers in October 1983, an emergency rule was imposed in Punjab, which would continue for more than a decade.[48]

Constitutional issues

The Akali Dal began more agitation in February 1984, protesting against Article 25, clause (2)(b), of the Indian Constitution, which ambiguously explains that "the reference to Hindus shall be construed as including a reference to persons professing the Sikh, Jaina, or Buddhist religion," while also implicitly recognizing Sikhism as a separate religion: "the wearing and carrying of kripans [sic] shall be deemed to be included in the profession of the Sikh religion."[59]:109 Even today, this clause is deemed offensive by many religious minorities in India due to its failure to recognise such religions separately under the constitution.[59]

Members of the Akali Dal demanded that the removal of any ambiguity in the Constitution that refers to Sikhs as Hindu, as such prompts various concerns for the Sikh population, both in principle and in practice. For instance, a Sikh couple who would marry in accordance to the rites of their religion would have to register their union either under the Special Marriage Act, 1954 or the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955. The Akalis demanded replacement of such rules with laws specific to Sikhism.

Operation Blue Star

Operation Blue Star was an Indian military operation ordered by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, between 1 and 8 June 1984, to remove militant religious leader Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale and his armed followers from the buildings of the Harmandir Sahib complex (aka the Golden Temple) in Amritsar, Punjab—the most sacred site in Sikhism.[60]

In July 1983, Akali Dal President Harchand Singh Longowal had invited Bhindranwale to take up residence at the sacred temple complex,[61] which Bhindranwale would later make into an armoury and headquarters for his armed uprising for Khalistan.[62][63]

Since the inception of the Dharam Yudh Morcha to the violent events leading up to Operation Blue Star, Khalistani militants had directly killed 165 Hindus and Nirankaris, as well as 39 Sikhs opposed to Bhindranwale, while a total of 410 dead and 1,180 injured came as result of Khalistani violence and riots.[64]

As negotiations held with Bhindranwale and his supporters proved unsuccessful, Indira Gandhi ordered the Indian Army to launch Operation Blue Star.[65] Along with the Army, the operation would involve Central Reserve Police Force, Border Security Force, and Punjab Police. Army units led by Lt. Gen. Kuldip Singh Brar (a Sikh), surrounded the temple complex on 3 June 1984. Just before the commencement of the operation, Lt. Gen. Brar addressed the soldiers:[66]

The action is not against the Sikhs or the Sikh religion; it is against terrorism. If there is anyone amongst them, who have strong religious sentiments or other reservations, and do not wish to take part in the operation he can opt out, and it will not be held against him.

— Lieutenant General Kuldip Singh Brar

However, none of the soldiers opted out, including many "Sikh officers, junior commissioned officers and other ranks."[66] Using a public address system, the Army repeatedly demanded the militants to surrender, asking them to at least allow pilgrims to leave the temple premises before commencing battle.

Nothing happened until 7:00 PM (IST).[67] The Army, equipped with tanks and heavy artillery, had grossly underestimated the firepower possessed by the militants, who attacked with anti-tank and machine-gun fire from the heavily fortified Akal Takht, and who possessed Chinese-made, rocket-propelled grenade launchers with armour-piercing capabilities. After a 24-hour shootout, the army finally wrested control of the temple complex.

Bhindranwale was killed in the operation, while many of his followers managed to escape. Army casualty figures counted 83 dead and 249 injured.[68] According to the official estimate presented by the Indian Government, the event resulted in a combined total of 493 militant and civilian casualties, as well as the apprehension of 1592 individuals.[69]

U.K. Foreign Secretary William Hague attributed high civilian casualties to the Indian Government's attempt at a full frontal assault on the militants, diverging from the recommendations provided by the U.K. Military.[lower-roman 3][lower-roman 4] Opponents of Gandhi also criticised the operation for its excessive use of force. Lieutenant General Brar later stated that the Government had "no other recourse" due to a "complete breakdown" of the situation: state machinery was under the militants' control; declaration of Khalistan was imminent; and Pakistan would have come into the picture declaring its support for Khalistan.[70]

Nonetheless, the operation did not crush Khalistani militancy, as it continued.[29]

Assassination of Indira Gandhi and anti-Sikh riots

On the morning of 31 October 1984, Indira Gandhi was assassinated in New Delhi by her two personal security guards Satwant Singh and Beant Singh, both Sikhs, in retaliation for Operation Blue Star.[29] The assassination would trigger the 1984 Anti-Sikh Riots across North India. While the ruling party, Indian National Congress (INC), maintained that the violence was due to spontaneous riots, its critics have alleged that INC members themselves had planned a pogrom against the Sikhs.[71]

The Nanavati Commission, a special commission created to investigate the riots, concluded that INC leaders (including Jagdish Tytler, H. K. L. Bhagat, and Sajjan Kumar) had directly or indirectly taken a role in the rioting incidents.[72][73] Union Minister Kamal Nath was accused of leading riots near Rakab Ganj, but was cleared due to lack of evidence.[73] Other political parties strongly condemned the riots.[74] Two major civil-liberties organisations issued a joint report on the anti-Sikh riots, naming 16 significant politicians, 13 police officers, and 198 others, accused by survivors and eyewitnesses.[75]

1985 to present day

1985

Rajiv-Longowal Accord

Many Sikh and Hindu groups, as well as organisations not affiliated to any religion, have attempted to establish peace between the Khalistan proponents and the Government of India. Akalis continued to witness radicalization of Sikh politics, fearing disastrous consequences.[31] In response, President Harchand Singh Longowal reinstated the head of the Akali Dal and pushed for a peace initiative that reiterated the importance of Hindu-Sikh amity, condemning Sikh extremist violence, therefore declaring that the Akali Dal was not in favor of Khalistan.

In 1985, The Government of India attempted to seek a political solution to the grievances of the Sikhs through the Rajiv-Longowal Accord, which took place between Longowal and Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. The Accord—recognizing the religious, territorial, and economic demands of the Sikhs that were thought to be non-negotiable under Indira Gandhi's tenure—agreed to establish commissions and independent tribunals in order to resolve the Chandigarh issue and the river dispute, laying the basis for Akali Dal's victory in the coming elections.[31]

Though providing a basis for a return to normality, Chandigarh evidently remained an issue and the agreement was denounced by Sikh militants who refused to give up the demand for an independent Khalistan. These extremists, who were left unappeased, would react by assassinating Longowal.[63] Such behavior would lead to the dismissal of negotiations, whereby both Congress and the Akali parties accused each other of aiding terrorism.[31]

The Indian Government pointed to the involvement of a “foreign hand,” referring to Pakistan’s abetting of the movement. Punjab noted to the Indian Government that militants were able to obtain sophisticated arms through sources outside the country and by developing links with sources within the country.[31] As such, the Government believed that large illegal flows of arms were flowing through the borders of India, with Pakistan being responsible for trafficking arms. India claimed that Pakistan provided sanctuary, arms, money, and moral support to the Sikhs, though most of the accusations were based on circumstantial evidence.[31]

Air India Flight 182

Air India Flight 182 was an Air India flight operating on the Montréal-London-Delhi-Bombay route. On 23 June 1985, a Boeing 747 operating on the route was blown up by a bomb mid-air off the coast of Ireland. A total of 329 people aboard were killed, [76] 268 Canadian citizens, 27 British citizens and 24 Indian citizens, including the flight crew. On the same day, an explosion due to a luggage bomb was linked to the terrorist operation and occurred at the Narita Airport in Tokyo, Japan, intended for Air India Flight 301, killing two baggage handlers. The entire event was inter-continental in scope, killing 331 people in total and affected five countries on different continents: Canada, the United Kingdom, India, Japan, and Ireland.

The main suspects in the bombing were members of a Sikh separatist group called the Babbar Khalsa, and other related groups who were at the time agitating for a separate Sikh state of Khalistan in Punjab, India. In September 2007, the Canadian Commission of Inquiry investigated reports, initially disclosed in the Indian investigative news magazine Tehelka,[77] that a hitherto unnamed person, Lakhbir Singh Rode, had masterminded the explosions. However, in conclusion two separate Canadian inquiries officially determined that the mastermind behind the terrorist operation was in fact the Canadian, Talwinder Singh Parmar.[78]

Several men were arrested and tried for the Air India bombing. Inderjit Singh Reyat, a Canadian national and member of the International Sikh Youth Federation who pleaded guilty in 2003 to manslaughter, would be the only person convicted in the case.[79][80] He was sentenced to fifteen years in prison for assembling the bombs that exploded on board Air India Flight 182 and at Narita Airport.[81]

Late 1980s

In 1986, when Sikh terrorism was at its peak, the Golden Temple was again occupied by militants belonging to the All India Sikh Students Federation and Damdami Taksal. The militants called an assembly (Sarbat Khalsa) and, on 26 January, they would pass a resolution (gurmattā) in favour of the creation of Khalistan.[82] However, only the Shiromani Gurdwara Parbandhak Committee (SGPC) had the authority to appoint the jathedar, the supreme religio-temporal seat of the Sikhs. The militants thus dissolved the SGPC and appointed their own jathedar, who turned out to refuse their bidding as well. Militant leader Gurbachan Singh Manochahal thereby appointed himself by force.[83]

On 29 April 1986, an assembly of separatist Sikhs at the Akal Takht made a declaration of an independent state of Khalistan,[84] and a number of rebel militant groups in favour of Khalistan subsequently waged a major insurgency against the Government of India. A decade of violence and conflict in Punjab would follow before a return to normality in the region. This period of insurgency saw clashes of Sikh militants with the police, as well as with the Nirankaris, a mystical Sikh sect who are less conservative in their aims to reform Sikhism.[85]

The Khalistani militant activities manifested in the form of several attacks, such as the 1987 massacre of 32 Hindu bus passengers near Lalru, and the 1991 killing of 80 train passengers in Ludhiana.[86] Such activities continued on into the 1990s as the perpetrators of the 1984 riots remained unpunished, while many Sikhs also felt that they were being discriminated against and that their religious rights were being suppressed.[87][88]

In the parliamentary elections of 1989, Sikh separatist representatives were victorious in 10 of Punjab's 13 national seats and had the most popular support.[89] The Congress cancelled those elections and instead hosted a Khaki election. The separatists boycotted the poll. The voter turnout was 24%. The Congress won this election and used it to further its anti-separatist campaign. Most of the separatist leadership was wiped out and the moderates were suppressed by end of 1993.[90]

1990s

Indian security forces suppressed the insurgency in the early 1990s, while Sikh political groups such as the Khalsa Raj Party and SAD (A) continued to pursue an independent Khalistan through non-violent means.[91][92][93] GlobalSecurity.org reported that in the early 1990s, journalists who did not conform to militant-approved behaviour were targeted for death.[88] It also reported that there were indiscriminate attacks designed to cause extensive civilian casualties: derailing trains, and exploding bombs in markets, restaurants, and other civilian areas between Delhi and Punjab. It further reported that militants assassinated many of those moderate Sikh leaders who opposed them, and sometimes killed rivals within the same militant group. It also stated that many civilians who had been kidnapped by extremists were murdered if the militants' demands were not met. Finally, it reported that Hindus left Punjab by the thousands.[88]

In August 1991, Julio Ribeiro, then-Indian Ambassador to Romania, was attacked and wounded at Bucharest in an assassination attempt by gunmen identified as Punjabi Sikhs.[94][87] Sikh groups also claimed responsibility for the 1991 kidnapping of Liviu Radu, the Romanian chargé d'affaires in New Delhi. This appeared to be in retaliation for Romanian arrests of Khalistan Liberation Force members suspected of the attempted assassination of Ribeiro.[87][95] Radu was released unharmed after Sikh politicians criticised the action.[96]

In October 1991, the New York Times reported that violence had increased sharply in the months leading up to the kidnapping, with Indian security forces or Sikh militants killing 20 or more people per day, and that the militants had been "gunning down" family members of police officers.[87] Scholar Ian Talbot states that all sides, including the Indian Army, police and the militants, committed crimes like murder, rape and torture.[97]

From 24 January 1993 to 4 August 1993, Khalistan was a member of the NGO Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. The membership was permanently suspended on 22 January 1995.[98]

On 31 August 1995, Chief Minister Beant Singh was killed in a suicide bombing, for which the pro-Khalistan group Babbar Khalsa claimed responsibility. Security authorities, however, reported the group's involvement to be doubtful.[99] A 2006 press release by the Embassy of the United States in New Delhi indicated that the responsible organisation was the Khalistan Commando Force.[100]

While the militants enjoyed some support among Sikh separatists in the earlier period, this support gradually disappeared.[101] The insurgency weakened the Punjab economy and led to an increase in violence in the state. With dwindling support and increasingly-effective Indian security troops eliminating anti-state combatants, Sikh militancy effectively ended by the early 1990s.[102]

2000s

Retribution

There have been serious charges levelled by human rights activists against Indian Security forces (headed by Sikh police officer, K. P. S. Gill), claiming that thousands of suspects were killed in staged shootouts and thousands of bodies were cremated/disposed of without proper identification or post-mortems.[103][104][105][106] Human Rights Watch reported that, since 1984, government forces had resorted to widespread human rights violations to fight the militants, including: arbitrary arrest, prolonged detention without trial, torture, and summary executions of civilians and suspected militants. Family members were frequently detained and tortured to reveal the whereabouts of relatives sought by the police.[107][108] Amnesty International has alleged several cases of disappearances, torture, rape, and unlawful detentions by the police during the Punjab insurgency, for which 75-100 police officers had been convicted by December 2002.[109]

Present-day activities

Present-day activities by Khalistani militants include the Tarn Taran blast, in which a police crackdown arrested 4 terrorists, one of whom revealed they were ordered by Sikhs for Justice to kill multiple Dera leaders in India.[110][111] Pro-Khalistan organisations such as Dal Khalsa are also active outside India, supported by a section of the Sikh diaspora.[112] As of December 25, there also have been inputs by multiple agencies about a possible attack in Punjab by Babbar Khalsa and Khalistan Zindabad Force who are in contact with their Pakistani handlers and are trying to smuggle arms across the border.[113][114]

In November 2015, a congregation of the Sikh community (i.e. a Sarbat Khalsa) was called in response to recent unrest in the Punjab region. The Sarbat Khalsa adopted 13 resolutions to strengthen Sikh institutions and traditions. The 12th resolution reaffirmed the resolutions adopted by the Sarbat Khalsa in 1986, including the declaration of the sovereign state of Khalistan.[115]

Moreover, signs in favour of Khalistan were raised when SAD (Amritsar) President Simranjeet Singh Mann met with Surat Singh Khalsa, who was admitted to Dayanand Medical College & Hospital (DMCH). While Mann was arguing with ACP Satish Malhotra, supporters standing at the main gate of DMCH raised Khalistan signs in the presence of heavy police force. After a confrontation with the police authorities that lasted about 15–20 minutes, Mann was allowed to meet Khalsa along with ADCP Paramjeet Singh Pannu.[116]

Despite residing outside India, there is a strong sense of attachment among Sikhs to their culture and religion. As such, Sikh groups operating from other countries could potentially revive the Khalistan Movement.[117] There is persistent demand for justice for the Sikh victims during the peak of the Khalistan movement. In some ways, The Sikh diaspora can be seen as torch-bearers of the Khalistan movement, which is now considered to be highly political and military in nature. Recent reports indicate a rise in pro-Khalistan sentiments among the Sikh diaspora overseas who can revive the secessionist movement. Some people were even spotted during the World Cup 2019 in pro-khalistan jerseys, but were then whisked out of the stadium.[117]

Recently, many signs have been raised in several places in support of the Khalistan movement, although the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRCC) reports that Sikhs who support Khalistan may themselves be detained and tortured.[118] Notably, on the 31st anniversary of Operation Bluestar, pro-Khalistan signs were raised in Punjab, resulting in 25 Sikh youths being detained by police.[119] Pro-Khalistan signs were also raised during a function of Punjabi Chief Minister Parkash Singh Badal. Two members of SAD-A, identified as Sarup Singh Sandha and Rajindr Singh Channa, raised pro-Khalistan and anti-Badal signs during the chief minister's speech.[120]

In retrospect, the Khalistan movement has failed to reach its objectives in India due to several reasons:

- Heavy Police crackdown on the separatists under the leadership of Punjab Police chief KPS Gill.[10] Several militant leaders were killed and others surrendered and rehabilitated.[83]

- Gill credits the decline to change in the policies by adding provision for an adequate number of Police and security forces to deal with the militancy. The clear political will from the government without any interference.[83]

- Lack of a clear political concept of 'Khalistan' even to the extremist supporters. As per Kumar (1997), the name which was wishful thinking only represented their revulsion against the Indian establishment and did not find any alternative to it.[121]

- In the later stages of the movement, militants lacked an ideological motivation.[83]

- The entry of criminals and government loyalists into its ranks further divided the groups.[83]

- Loss of sympathy and support from the Sikh population of Punjab.[83]

- The divisions among the Sikhs also undermined this movement. According to Pettigrew non-Jat urban Sikhs did not want to live in a country of "Jatistan."[122][123] Further division was caused as the people in the region traditionally preferred police and military service as career options. The Punjab Police had a majority of Jat Sikhs and the conflict was referred as "Jat against Jat" by Police Chief Gill.[83]

- Moderate factions of Akali Dal led by Prakash Singh Badal reclaimed the political positions in the state through all three assembly (namely parliamentary) and SGPC elections. The dominance of traditional political parties was reasserted over the militant-associated factions.[124]

- The increased vigilance by security forces in the region against rise of separatist elements.[125]

- The confidence building measures adopted by the Sikh community helped in rooting out the Khalistan movement.[125]

Simrat Dhillon (2007), writing for the Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies, noted that while a few groups continued to fight, "the movement has lost its popular support both in India and within the Diaspora community."[126]

Militancy

During the late 1980s and the early 1990s, there was a dramatic rise in radical State militancy in Punjab. The 1984 military Operation Blue Star in the Golden Temple in Amritsar offended many Sikhs.[127] The separatists used this event, as well as the following Anti-Sikh Riots, to claim that the interest of Sikhs was not safe in India and to foster the spread of militancy among Sikhs in Punjab. Some sections of the Sikh diaspora also began join the separatists with financial and diplomatic support.[29]

A section of Sikhs turned to militancy in Punjab and several Sikh militant outfits proliferated in the 1980s and 1990s.[27] Some militant groups aimed to create an independent state through acts of violence directed at members of the Indian government, army, or forces. A large numbers of Sikhs condemned the actions of the militants.[128] According to Anthropological analysis, one reason young men had for joining militant and other religious nationalist groups was for fun, excitement, and expressions of masculinity. Puri, Judge, and Sekhon (1999) suggest that illiterate/under-educated young men, lacking enough job prospects, had joined pro-Khalistan militant groups for the primary purpose of "fun."[129] They mention that the pursuit of Khalistan itself was the motivation for only 5% of "militants."[124][129]

Militant groups

There are several militant Sikh groups, such as the Khalistan Council, that are currently functional and provides organization and guidance to the Sikh community. Multiple groups are organized across the world, coordinating their military efforts for Khalistan. Such groups were most active in 1980s and early 1990s, and have since receded in activity. These groups are largely defunct in India but they still have a political presence among the Sikh diaspora, especially in countries such as Pakistan where they are not prescribed by law.[130]

Most of these outfits were crushed by 1993 during the counter-insurgency operations. In recent years, active groups have included Babbar Khalsa, International Sikh Youth Federation, Dal Khalsa, and Bhindranwale Tiger Force. An unknown group before then, the Shaheed Khalsa Force claimed credit for the marketplace bombings in New Delhi in 1997. The group has never been heard of since.

Major pro-Khalistan militant outfits include:

- Babbar Khalsa International (BKI)

- Listed as a terrorist organisation in the European Union,[131] Canada,[132] India,[133] and UK.[133][134]

- Included in the Terrorist Exclusion List of the U.S. Government in 2004.[135]

- Designated by the US and the Canadian courts for the bombing of Air India Flight 182 on 27 June 2002.[133][136]

- Bhindranwala Tiger Force of Khalistan (BTFK; aka Bhindranwale Tiger Force, BTF)

- This group appears to have been formed in 1984 by Gurbachan Singh Manochahal.

- Seems to have disbanded or integrated into other organisations after the death of Manochahal.[137]

- Listed in 1995 as one of the 4 "major militant groups" in the Khalistan movement.[138]

- Khalistan Commando Force (KCF)[27]

- Formed by the Sarbat Khalsa in 1986.[139] It does not figure in the list of terrorist organisations declared by the U.S. Department of State (DOS).[140]

- According to the DOS [100] and the Assistant Inspector General of the Punjab Police Intelligence Division,[141] the KCF was responsible for the deaths of thousands in India, including the 1995 assassination of Chief Minister Beant Singh.[100]

- Khalistan Liberation Army (KLA)

- Reputed to have been a wing of, associated with, or a breakaway group of the Khalistan Liberation Force.

- Khalistan Liberation Force[27]

- Formed in 1986

- Believed to be responsible for several bombings of civilian targets in India during the 1980s and 1990s,[142][143] sometimes in conjunction with Islamist Kashmir separatists.[144]

- Khalistan Zindabad Force (KZF)

- Listed as a terrorist organisation by the EU.[131]

- Last major suspected activity was a bomb blast in 2006 at the Inter-State Bus Terminus in Jalandhar.[145]

- International Sikh Youth Federation (ISYF),[27] based in the United Kingdom.

- All India Sikh Students Federation (AISSF)

- Dashmesh Regiment

- Shaheed Khalsa Force

Abatement of extremism

The U.S. Department of State found that Sikh extremism had decreased significantly from 1992 to 1997, although a 1997 report noted that "Sikh militant cells are active internationally and extremists gather funds from overseas Sikh communities."[146]

In 1999, Kuldip Nayar, writing for Rediff.com, stated in an article, titled "It is fundamentalism again", that the Sikh "masses" had rejected terrorists.[147] By 2001, Sikh extremism and the demand for Khalistan had all but abated.[lower-roman 5]

Reported in his paper, titled "From Bhindranwale to Bin Laden: Understanding Religious Violence", Director Mark Juergensmeyer of the Orfalea Centre for Global & International Studies, UCSB, interviewed a militant who said that "the movement is over," as many of his colleagues had been killed, imprisoned, or driven into hiding, and because public support was gone.[148]

Outside of India

Operation Blue Star and its violent aftermaths popularized the demand for Khalistan among many Sikhs dispersed globally.[149] Involvement of sections of Sikh diaspora turned out to be important for the movement as it provided the diplomatic and financial support. It also enabled Pakistan to become involved in the fueling of the movement. Sikhs in UK, Canada and USA arranged for cadres to travel to Pakistan for military and financial assistance. Some Sikh groups abroad even declared themselves as the Khalistani government in exile.[29]

The Sikh place of worship, gurdwaras provided the geographic and institutional coordination for the Sikh community. Sikh political factions have used the gurdwaras as a forum for political organization. The gurdwaras sometimes served as the site for mobilization of diaspora for Khalistan movement directly by raising funds. Indirect mobilization was sometimes provided by promoting a stylized version of conflict and Sikh history. The rooms in some gurdwara exhibit pictures of Khalistani leaders along with paintings of martyrs from Sikh history. Gurdwaras also host speakers and musical groups that promote and encourage the movement. Among the diasporas, Khalistan issue has been a divisive issue within gurdwaras. These factions have fought over the control of gurdwaras and their political and financial resources. The fights between pro and anti-Khalistan factions over gurdwaras often included violent acts and bloodshed as reported from UK and North America. The gurdwaras with Khalistani leadership allegedly funnel the collected funds into activities supporting the movement.[150]

Different groups of Sikhs in the diaspora organize the convention of international meetings to facilitate communication and establish organizational order. In April 1981 the first "International Convention of Sikhs," was held in New York and was attended by some 200 delegates. In April 1987 the third convention was held in Slough, Berkshire where the Khalistan issue was addressed. This meeting's objective was to "build unity in the Khalistan movement."[150] All these factors further strengthened the emerging nationalism among Sikhs. Sikh organizations launched many fund-raising efforts that were used for several purposes. After 1984 one of the objectives was the promotion of the Sikh version of "ethnonational history" and the relationship with the Indian state. The Sikh diaspora also increased their efforts to build institutions to maintain and propagate their ethnonational heritage. A major objective of these educational efforts was to publicize a different face to the non Sikh international community who regarded the Sikhs as "terrorists."[151]

In 1993, Khalistan was briefly admitted in the Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization, but was suspended in a few months. The membership suspension was made permanent on 22 January 1995.[152][153]

Pakistan

Pakistan has long aspired to dismember India through its Bleed India strategy. Even before the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, then a member of the military regime of General Yahya Khan, stated, "Once the back of Indian forces is broken in the east, Pakistan should occupy the whole of Eastern India and make it a permanent part of East Pakistan.... Kashmir should be taken at any price, even the Sikh Punjab and turned into Khalistan."[154]

General Zia-ul Haq, who succeeded Bhutto as the Head of State, attempted to reverse the traditional antipathy between Sikhs and Muslims arising from the partition violence by restoring Sikh shrines in Pakistan and opening them for Sikh pilgrimage. The expatriate Sikhs from England and North America that visited these shrines were at the forefront of the calls for Khalistan. During the pilgrims' stay in Pakistan, the Sikhs were exposed to Khalistani propaganda, which would not be openly possible in India.[155][156][130] The ISI chief, General Abdul Rahman, opened a cell within ISI with the objective of supporting the "[Sikhs']...freedom struggle against India". Rahman's colleagues in ISI took pride in the fact that "the Sikhs were able to set the whole province on fire. They knew who to kill, where to plant a bomb and which office to target." General Hamid Gul argued that keeping Punjab destabilized was equivalent to the Pakistan Army having an extra division at no cost. Zia-ul Haq, on the other hand, consistently practised the art of plausible denial.[155][156] The Khalistan movement was brought to a decline only after India fenced off a part of the Punjab border with Pakistan and the Benazir Bhutto government agreed to joint patrols of the border by Indian and Pakistani troops.[157]

In 2006, an American Court convicted Khalid Awan, a Muslim and Canadian of Pakistani descent, of "supporting terrorism" by providing money and financial services to the Khalistan Commando Force chief Paramjit Singh Panjwar in Pakistan.[100] KCF members had carried out deadly attacks against Indian civilians causing thousands of deaths. Awan frequently travelled to Pakistan and was alleged by the U.S. officials with links to Sikh and Muslim extremists, as well as Pakistani intelligence.[158]

In 2008, India's Intelligence Bureau indicated that Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence organisation was trying to revive Sikh militancy.[159]

United States

The New York Times reported in June 1984 that Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi conveyed to Helmut Schmidt and Willy Brandt, both of them being former Chancellors of West Germany, that United States' Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) was involved in causing unrest in Punjab. It also reported that The Indian Express quoted anonymous officials from India's Intelligence establishment as saying that the CIA "masterminded" a plan to support the acolytes of Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, who died a few days ago during Operation Blue Star, by smuggling weapons for them through Pakistan.[160] The United States embassy denied this report's findings.[160]

According to B. Raman, former Additional Secretary in the Cabinet Secretariat of India and a senior official of the Research and Analysis Wing, the United States initiated a plan in complicity with Pakistan's General Yahya Khan in 1971 to support an insurgency for Khalistan in Punjab.[161][162]

Canada

Immediately after Operation Blue Star, authorities were unprepared for how quickly extremism spread and gained support in Canada, with extremists "...threatening to kill thousands of Hindus by a number of means, including blowing up Air India flights."[163][164] Canadian Member of Parliament Ujjal Dosanjh, a moderate Sikh, stated that he and others who spoke out against Sikh extremism in the 1980s faced a "reign of terror".[165]

On 18 November 1998, the Canada-based Sikh journalist Tara Singh Hayer was gunned down by suspected Khalistani militants. The publisher of the "Indo-Canadian Times," a Canadian Sikh and once-vocal advocate of the armed struggle for Khalistan, he had criticised the bombing of Air India flight 182, and was to testify about a conversation he overheard concerning the bombing.[166][167] On 24 January 1995,[168] Tarsem Singh Purewal, editor of Britain's Punjabi-language weekly "Des Pardes", was killed as he was closing his office in Southall. There is speculation that the murder was related to Sikh extremism, which Purewal may have been investigating. Another theory is that he was killed in retaliation for revealing the identity of a young rape victim.[169][170]

Terry Milewski reported in a 2007 documentary for the CBC that a minority within Canada's Sikh community was gaining political influence even while publicly supporting terrorist acts in the struggle for an independent Sikh state.[133] In response, the World Sikh Organization of Canada (WSO), a Canadian Sikh human rights group that opposes violence and extremism,[171] sued the CBC for "defamation, slander, and libel", alleging that Milewski linked it to terrorism and damaged the reputation of the WSO within the Sikh community.[172] In 2015, however, the WSO unconditionally abandoned "any and all claims" made in its lawsuit.

Canadian journalist Kim Bolan has written extensively on Sikh extremism. Speaking at the Fraser Institute in 2007, she reported that she still received death threats over her coverage of the 1985 Air India bombing.[173]

In 2008, a CBC report stated that "a disturbing brand of extremist politics has surfaced" at some of the Vaisakhi parades in Canada,[133] and The Trumpet agreed with the CBC assessment.[174] Two leading Canadian Sikh politicians refused to attend the parade in Surrey, saying it was a glorification of terrorism.[133] In 2008, Dr. Manmohan Singh, Prime Minister of India, expressed his concern that there might be a resurgence of Sikh extremism.[175][176]

There has been some controversy over Canada's response to the Khalistan movement. After Amarinder Singh's refusal to meet Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in 2017, calling him a "Khalistani sympathizer", Singh ultimately met with Trudeau 22 Feb 2018 over the issue.[177] Trudeau assured Singh that his country would not support the revival of the separatist movement.[178][9][179] Shiromani Akali Dal President Sukhbir Badal was quoted saying Khalistan is "no issue, either in Canada or in Punjab".[180] Justin Trudeau has declared that his country would not support the revival of the separatist movement.[9]

United Kingdom

In February 2008, BBC Radio 4 reported that the Chief of the Punjab Police, NPS Aulakh, alleged that militant groups were receiving money from the British Sikh community.[181] The same report included statements that although the Sikh militant groups were poorly equipped and staffed, intelligence reports and interrogations indicated that Babbar Khalsa was sending its recruits to the same terrorist training camps in Pakistan used by Al Qaeda.[182]

Lord Bassam of Brighton, then Home Office minister, stated that International Sikh Youth Federation (ISYF) members working from the UK had committed "assassinations, bombings, and kidnappings" and were a "threat to national security."[79] The ISYF is listed in the UK as a "Proscribed Terrorist Group" [134] but it has not been included in the list of terrorist organisations by the United States Department of State.[183] It was also added to the US Treasury Department terrorism list on 27 June 2002.[184]

Andrew Gilligan, reporting for The London Evening Standard, stated that the Sikh Federation (UK) is the "successor" of the ISYF, and that its executive committee, objectives, and senior members ... are largely the same.[79][185] The Vancouver Sun reported in February 2008 that Dabinderjit Singh was campaigning to have both the Babbar Khalsa and International Sikh Youth Federation de-listed as terrorist organisations.[186] It also stated of Public Safety Minister Stockwell Day that "he has not been approached by anyone lobbying to delist the banned groups". Day is also quoted as saying "The decision to list organizations such as Babbar Khalsa, Babbar Khalsa International, and the International Sikh Youth Federation as terrorist entities under the Criminal Code is intended to protect Canada and Canadians from terrorism."[186] There are claims of funding from Sikhs outside India to attract young people into these pro-Khalistan militant groups.[187]

See also

References

Notes

- Mehtab Ali Shah, The Foreign Policy of Pakistan 1997, pp. 24–25:

- Reuters. 14 March 1984. "Around the World; Former Punjab Leader Escapes Assassination." The New York Times. "Darbara Singh, the former Chief Minister of Punjab state, escaped assassination today when gunmen fired at him while he was attending a funeral."

- Hague, William. 2014. "Allegations of UK Involvement in the Indian Operation at Sri Harmandir Sahib, Amritsar 1984." (Policy paper). Available as a PDF. Retrieved 17 May 2020. "The FCO files (Annex E) record the Indian Intelligence Co-ordinator telling a UK interlocutor, in the same time-frame as this public Indian report, that some time after the UK military adviser’s visit the Indian Army took over lead responsibility for the operation, the main concept behind the operation changed, and a frontal assault was attempted, which contributed to the large number of casualties on both sides."

- "Golden Temple attack: UK advised India but impact 'limited'." BBC News. 7 June 2014. Retrieved 17 May 2020. "The adviser suggested using an element of surprise, as well as helicopters, to try to keep casualty numbers low - features which were not part of the final operation, Mr Hague said."

- Jodhka (2001): "Not only has the once powerful Khalistan movement virtually disappeared, even the appeal of identity seems to have considerably declined during the last couple of years."

Citations

- Kinnvall, Catarina. 2007. "Situating Sikh and Hindu Nationalism in India." In Globalization and Religious Nationalism in India: The Search for Ontological Security, (Routledge Advances in International Relations and Global Politics 46). London: Routledge. ISBN 9781134135707.

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/41856545?seq=1

- Crenshaw, Martha. 1995. Terrorism in Context. Pennsylvania State University. ISBN 978-0-271-01015-1. p. 364.

- Gupta, Shekhar; Subramanian, Nirupaman (15 December 1993). "You can't get Khalistan through military movement: Jagat Singh Chouhan". India Today. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- Axel, Brian Keith (2001). The Nation's Tortured Body: Violence, Representation, and the Formation of a Sikh "Diaspora". Duke University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-8223-2615-1.

The call for a Sikh homeland was first made in the 1930s, addressed to the quickly dissolving empire.

- Shani, Giorgio (2007). Sikh Nationalism and Identity in a Global Age. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-134-10189-4.

However, the term Khalistan was first coined by Dr V.S. Bhatti to denote an independent Sikh state in March 1940. Dr Bhatti made the case for a separate Sikh state in a pamphlet entitled 'Khalistan' in response to the Muslim League's Lahore Resolution.

- Bianchini, Stefano; Chaturvedi, Sanjay; Ivekovic, Rada; Samaddar, Ranabir (2004). Partitions: Reshaping States and Minds. Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-134-27654-7.

Around the same time, a pamphlet of about forty pages, entitled 'Khalistan', and authored by medical doctor, V.S. Bhatti, also appeared.

- "Jagmeet Singh now rejects glorification of Air India bombing mastermind". CBC News. 15 March 2018.

The 18-month long Air India inquiry, led by former Supreme Court justice John Major, pointed to Parmar as the chief terrorist behind the bombing. A separate inquiry, carried out by former Ontario NDP premier and Liberal MP Bob Rae, also fingered Parmar as the architect of the 1985 bombing that left 329 people dead 268 of them Canadians.

- "India gives Trudeau list of suspected Sikh separatists in Canada". Reuters. 22 February 2018.

The Sikh insurgency petered out in the 1990s. He told state leaders his country would not support anyone trying to reignite the movement for an independent Sikh homeland called Khalistan.

- "New brand of Sikh militancy: Suave, tech-savvy pro-Khalistan youth radicalised on social media". Hindustan Times.

- Ali, Haider (6 June 2018). "Mass protests erupt around Golden Temple complex as pro-Khalistan sikhs mark Blue Star anniversary". Daily Pakistan. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- "UK: Pakistani-origin lawmaker leads protests in London to call for Kashmir, Khalistan freedom". Scroll. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- Bhattacharyya, Anirudh (5 June 2017). "Pro-Khalistan groups plan event in Canada to mark Operation Bluestar anniversary". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- Majumdar, Ushinor. "Sikh Extremists In Canada, The UK And Italy Are Working With ISI Or Independently". Outlook India.

Q. Is it clear which ‘foreign hand’ is driving this entire nexus? A. Evidence gathered by the police and other agencies points to the ISI as the key perpetrator of extremism in Punjab. (Amarinder Singh Indian Punjab Chief Minister)

- Wallace, Paul (1986). "The Sikhs as a "Minority" in a Sikh Majority State in India". Asian Survey. 26 (3): 363–377. doi:10.2307/2644197. ISSN 0004-4687. JSTOR 2644197.

Over 8,000,000 of India's 10,378,979 Sikhs were concentrated in Punjab

- Jolly, Sikh Revivalist Movements (1988), p. 6.

- Purewal, Navtej K. (2017). Living on the Margins: Social Access to Shelter in Urban South Asia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-74899-5.

The wrangling between various Sikh groupings were resolved by the nineteenth century when Maharajah Ranjit Singh unified the Punjab from Peshawar t the Sutluj River.

- Panton, Kenneth J. (2015). Historical Dictionary of the British Empire. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 470. ISBN 978-0-8108-7524-1.

A second conflict, just two years later, led to complete subjugation of the Sikhs and the incorporation of the remainder of their lands

- Fair, Diaspora Involvement in Insurgencies (2005), p. 127.

- Axel, Brian Keith (2001). The Nation's Tortured Body: Violence, Representation, and the Formation of a Sikh "Diaspora". Duke University Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-8223-2615-1.

The Akalis viewed the Lahore Resolution and the Cripps Mission as a betrayal of the Sikhs and an attempt to usurp what, since the time of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, was historically a Sikh territory.

- Tan, Tai Yong; Kudaisya, Gyanesh (2005) [First published 2000], The Aftermath of Partition in South Asia, Routledge, p. 100, ISBN 978-0-415-28908-5,

The professed intention of the Muslim League to impose a Muslim state on the Punjab (a Muslim majority province) was anathema to the Sikhs ... the Sikhs launched a virulent campaign against the Lahore Resolution ... Sikh leaders of all political persuasions made it clear that Pakistan would be 'wholeheartedly resisted'.

- Axel, Brian Keith (2001). The Nation's Tortured Body: Violence, Representation, and the Formation of a Sikh "Diaspora". Duke University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-8223-2615-1.

Against the nationalist ideology of a united India, which called for all groups to set aside "communal" differences, the Shiromani Akali Dal Party of the 1930s rallied around the proposition of a Sikh panth (community) that was separate from Hindus and Muslims.

- Shani, Giorgio (2007). Sikh Nationalism and Identity in a Global Age. Routledge. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-134-10189-4.

Khalistan was imagined as a theocratic state, a mirror-image of 'Muslim' Pakistan, led by the Maharaja of Patiala with the aid of a cabinet consisting of representing federating units.

- Shah, Mehtab Ali (1997), The Foreign Policy of Pakistan: Ethnic Impacts on Diplomacy 1971-1994, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 9781860641695

- Hill, K.; Seltzer, W.; Leaning, J.; Malik, S.J.; Russell, S. S.; Makinson, C. (2003), A Demographic Case Study of Forced Migration: The 1947 Partition of India, Harvard University Asia Center, archived from the original on 6 December 2008

- McLeod, W. H. (1989), The Sikhs: History, Religion, and Society, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-06815-4

- Fair, Diaspora Involvement in Insurgencies (2005), p. 129.

- Fair, Diaspora Involvement in Insurgencies (2005), p. 130.

- Fair, Diaspora Involvement in Insurgencies (2005), p. 128.

- Fair, Diaspora Involvement in Insurgencies (2005), p. 134.

- Jetly, Rajshree. 2006. “The Khalistan Movement in India: The Interplay of Politics and State Power.” International Review of Modern Sociology 34(1):61–62. JSTOR 41421658.

- "Hindu-Sikh relations — I". The Tribune. Chandigarh, India: Tribuneindia.com. 3 November 2003. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011.

- Chawla, Muhammad Iqbal. 2017. The Khalistan Movement of 1984: A Critical Appreciation.

- "The Punjab Reorganisation Act, 1966" (PDF). Government of India. 18 September 1966. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2012.

- Mitra, Subrata K. (2007), The Puzzle of India's Governance: Culture, Context and Comparative Theory, Advances in South Asian Studies: Routledge, p. 94, ISBN 9781134274932

- Singh, Khushwant (2004), "The Anandpur Sahib Resolution and Other Akali Demands", A History of the Sikhs: Volume 2: 1839-2004, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195673098.001.0001, ISBN 9780195673098

- Ray, Jayanta Kumar (2007), Aspects of India's International Relations, 1700 to 2000: South Asia and the World, Pearson Education India, p. 484, ISBN 9788131708347

- Akshayakumar Ramanlal Desai (1 January 1991), Expanding Governmental Lawlessness and Organized Struggles, Popular Prakashan, pp. 64–66, ISBN 978-81-7154-529-2

- Fair, Diaspora Involvement in Insurgencies (2005), p. 135.

- Pandya, Haresh (11 April 2007). "Jagjit Singh Chauhan, Sikh Militant Leader in India, Dies at 80". The New York Times.

- Axel, The Nation's Tortured Body (2011), pp. 101–

- Jo Thomas (14 June 1984). "London Sikh Assumes Role of Exile Chief". The New York Times.

- Van Dyke, The Khalistan Movement (2009), p. 980.

- Tambiah, Leveling Crowds (1996), p. 106

- "Pradhanmantri Episode 14". ABP News. 25 January 2018.

- India. 10 July 1984. "White Paper on the Punjab Agitation." New Delhi: Government of India Press. OL 21839009M. p. 40.

- Sundari, M. Arokia Selva, and K. Sasikala. 2019. "Operation Blue Star and White Paper on Punjab Agitation." Think India Journal 22(10):9361–71. ISSN 0971-1260.

- Sisson, Mary. 2011. "Sikh Terrorism." Pp. 544–545 in The SAGE Encyclopedia of Terrorism (2nd ed.), edited by G. Martin. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-4129-8016-6. doi:10.4135/9781412980173.n368.

- Singh, Tavleen. 2000. "Prophet of Hate: J S Bhindranwale | 100 People Who Shaped India." India Today. New Delhi: Living Media. Archived from the original on 20 June 2008.

- Deol, Religion and Nationalism in India (2000), pp. 102–106.

- Chima, Jugdep S. (2008). The Sikh Separatist Insurgency in India: Political Leadership and Ethnonationalist Movements. SAGE Publications India. p. 64. ISBN 978-81-321-0538-1. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

... an Indian Airlines plane was hijacked by Dal Khasa activists.

- Chima, Jugdep S (2008), The Sikh Separatist Insurgency in India: Political Leadership and Ethnonationalist Movements, India: SAGE Publications, pp. 71–75, ISBN 9788132105381

- Sharma, Sanjay (5 June 2011). "Bhajan Lal lived with 'anti-Sikh, anti-Punjab' image". The Times of India.

- Stepan, Alfred, Juan J. Linz, Yogendra Yadav (2011), Crafting State-Nations: India and Other Multinational Democracies (Illustrated ed.), JHU Press, p. 97, ISBN 9780801897238

- Ghosh, Srikanta. 1997. Indian Democracy Derailed – Politics and Politicians. APH Publishing. ISBN 9788170248668. p. 95.

- "Martyr's Gallery". Punjab Police. Government of India. 2015. Archived from the original on 21 March 2017. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- Sharma, Puneet, dir. 2013. "Operation Blue Star and the assassination of Indira Gandhi" (tv episode). Pradhanmantri Ep. 14. India: ABP News. – via ABP News Hindi on YouTube.

- Verma, Arvind. 2003. "Terrorist Victimization: Prevention, Control, and Recovery, Case Studies from India." Pp. 89–98 in Meeting the Challenges of Global Terrorism: Prevention, Control, and Recovery, edited by D. K. Das and P. C. Kratcoski. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-0499-6. p. 89.

- Sharma, Mool Chand, and A.K. Sharma, eds. 2004. "Discrimination Based on Religion." Pp. 108–110 in Discrimination Based on Sex, Caste, Religion, and Disability. New Delhi: National Council for Teacher Education. Archived from the original on 2 June 2010. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Swami, Praveen (16 January 2014). "RAW chief consulted MI6 in build-up to Operation Bluestar". The Hindu. Chennai, India.

- Singh, Khushwant. 2004. A History of the Sikhs, Volume II: 1839-2004. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. p. 337.

- Subramanian, L. N. 2006. "Operation Blue Star, 05 June 1984." Bharat Rakshak Monitor 3(2). Archived from the original on 8 April 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Sikh Leader in Punjab Accord Assassinated". LA Times. Times Wire Services. 21 August 1985.

- Tully, Mark, and Satish Jacob. 1985. Amritsar: Mrs. Gandhi's Last Battle (5th ed.). London: Jonathan Cape. p. 147.

- Wolpert, Stanley A., ed. (2009). "India". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Gates, Scott, and Kaushik Roy. 2016. "Insurgency and Counterinsurgency in Punjab." Pp. 163–175 in Unconventional Warfare in South Asia: Shadow Warriors and Counterinsurgency. Surrey: Ashgate. ISBN 978-1-317-00541-4. p. 167.

- Diwanji, Amberish K. (4 June 2004). "There is a limit to how much a country can take". The Rediff Interview/Lieutenant General Kuldip Singh Brar (retired). Rediff.com.

- Walia, Varinder. 19 March 2007. "Army reveals startling facts on Bluestar, says Longowal surrendered." The Tribune. Amritsar: Tribune News Service.

- India. 10 July 1984. "White Paper on the Punjab Agitation." New Delhi: Government of India Press. OL 21839009M. p. 40.

- "Pakistan would have recognised Khalistan". Rediff.com. 3 June 2004.

- Guidry, John A., Michael D. Kennedy, and Mayer N. Zald, eds. 2000. Globalizations and Social Movements: Culture, Power, and the Transnational Public Sphere. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-06721-3. p. 319.

- Nanavati, G. T. 9 February 2005. "Report of the Justice Nanavati Commission of Inquiry (1984 Anti-Sikh Riots)" 1. New Delhi: Ministry of Home Affairs. Archived from the original 27 November 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2020. Also available via People's Archive of Rural India.

- "What about the big fish?". Tehelka. Anant Media. 25 August 2005. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012.

- Singh, Swadesh Bahadur. 31 May 1996. "Cabinet berth for a Sikh." Indian Express.

- Kumar, Ram Narayan, et al. 2003. Reduced to Ashes: The Insurgency and Human Rights in Punjab. South Asia Forum for Human Rights. p. 43. Available via Committee for Information and Initiative on Punjab.

- In Depth: Air India - The Victims, CBC News Online, 16 March 2005

- "Free. Fair. Fearless". Tehelka. Archived from the original on 12 September 2012.

- "Jagmeet Singh now rejects glorification of Air India bombing mastermind". CBC News. 15 March 2018.

- Gilligan, Andrew (21 April 2008). "Ken's adviser is linked to terror group". The London Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 12 June 2009. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- Bolan, Kim (February 9, 2008). "Air India bombmaker sent to holding centre". Ottawa Citizen. Archived from the original on November 9, 2012. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

- "Convicted Air India bomb-builder Inderjit Singh Reyat gets bail". CBC News. July 9, 2008. Archived from the original on July 10, 2008. Retrieved June 10, 2009.

- "Sikh Temple Sit-In Is a Challenge for Punjab." The New York Times. 2 February 1986.

- Van Dyke, The Khalistan Movement (2009), p. 990.

- Singh, I. "Sarbat Khalsa and Gurmata". SikhNet. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- "Sant Nirankari Mission".

- "Gunmen Slaughter 32 on Bus in India in Bloodiest Attack of Sikh Campaign". The Philadelphia Inquirer, 7 July 1987. Page A03.

- Gargan, Edward (10 October 1991). "Envoy of Romania Abducted in India". The New York Times.

- "Military:Sikhs in Punjab". globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 31 May 2009.

- Gurharpal Singh, Ethnic Conflict in India (2000), Chapters 8 & 9.

- Gurharpal Singh, Ethnic Conflict in India (2000), Chapter 10.

- "Amnesty International report on Punjab". Amnesty International. 20 January 2003. Archived from the original on 3 December 2006.

- "The Tribune, Chandigarh, India - Punjab". Tribuneindia.com. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- "SAD (A) to contest the coming SGPC elections on Khalistan issue: Mann". PunjabNewsline.com. 14 January 2010. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011.

- "Gunmen Wound India Ambassador". The Los Angeles Times. 21 August 1991.

- "World Notes India", Time magazine, 21 October 1991.

- "Secret Injustice: The Harpal Singh Case" Archived 8 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Sikh Sentinel, 17 Sep 2003.

- Talbot, India and Pakistan (2000), p. 272.

- Simmons, Mary Kate (1998). Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization: yearbook. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 187. ISBN 9789041102232. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- "Issue Paper INDIA: Sikhs in Punjab 1994-95". Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. February 1996. Retrieved 31 May 2009.

- "U.S. Court Convicts Khalid Awan for Supporting Khalistan Commando Force". The United States Attorney's Office. 20 December 2006. Archived from the original on 15 January 2012. Retrieved 26 December 2011.

- Mahmood, Cynthia. 5 May 1997. "Fax to Ted Albers." Orono, Maine: Resource Information Center.

- Documentation, Information and Research Branch. 17 February 1997. "India: Information from four specialists on the Punjab, Response to Information Request #IND26376.EX." Ottawa: Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada.

- "Protecting the Killers: A Policy of Impunity in Punjab, India: I. Summary". Human Rights Watch. 9 October 2006. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- Special Broadcasting Service:: Dateline - presented by George Negus Archived 28 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Hindu: Opinion / News Analysis: Is justice possible without looking for the truth?". The Hindu. 9 September 2005. Archived from the original on 22 May 2008.

- "India: A vital opportunity to end impunity in Punjab". Amnesty International USA. Archived from the original on 25 June 2009.

- "ASW". Hrw.org. 1992. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- Time for India to Deliver Justice in Punjab Archived 2 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Human Rights Watch

- "Document - India: Break the cycle of impunity and torture in Punjab | Amnesty International". Amnesty International. 2003. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- Ch, Manjeet Sehgal; igarhSeptember 23; September 23, 2019UPDATED; Ist, 2019 11:58. "Punjab: Four Khalistan Zindabad Force terrorists arrested in Taran Taran". India Today. Retrieved 27 December 2019.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Service, Tribune News. "NIA demands custody of 4 in Tarn Taran blast case". Tribuneindia News Service. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- Punj, Balbair (16 June 2005). "The Ghost of Khalistan". Sikh Times.

- "Terror attacks in Punjab being planned by pro-Khalistan outfits with Pak's support: Intelligence sources". DNA India. 26 December 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- Nanjappa, Vicky (26 December 2019). "High alert declared after IB picks up intercepts on possible terror attack in Punjab". Oneindia. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- "Official Resolutions From Sarbat Khalsa 2015". Sikh24.com. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- "Khalistan slogans raised as Mann comes to meet Khalsa". The Indian Express. 25 July 2015.

- "Probable Resurgence of the Khalistan Movement: Role of the Sikh Diaspora - Science, Technology and Security forum". stsfor.org.