Tatarstan

The Republic of Tatarstan (Russian: Респу́блика Татарста́н, romanized: Respúblika Tatarstán; Tatar: Татарстан Республикасы), or simply Tatarstan, also called Tatariya[15] (Russian: Татарста́н, romanized: Tatarstán; Tatar: Татарстан), is a federal subject (a republic) of the Russian Federation, located in the Volga Federal District. Its capital is the city of Kazan.

Republic of Tatarstan | |

|---|---|

| Республика Татарстан | |

| Other transcription(s) | |

| • Tatar | Татарстан Республикасы |

Coat of arms | |

| Anthem: State Anthem of the Republic of Tatarstan | |

| |

| Coordinates: 55°33′N 50°56′E | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal district | Volga[2] |

| Economic region | Volga[3] |

| Established | May 27, 1920[4] |

| Capital | Kazan[5] |

| Government | |

| • Body | State Council[6] |

| • President[6] | Rustam Minnikhanov[7] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 68,000 km2 (26,000 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 44th |

| Population (2010 Census)[9] | |

| • Total | 3,786,488 |

| • Estimate (2018)[10] | 3,894,284 (+2.8%) |

| • Rank | 8th |

| • Density | 56/km2 (140/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 75.4% |

| • Rural | 24.6% |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK |

| ISO 3166 code | RU-TA |

| License plates | 16, 116, 716 |

| OKTMO ID | 92000000 |

| Official languages | Russian;[12] Tatar[13][14] |

| Website | http://tatarstan.ru/eng/ |

The republic borders Kirov, Ulyanovsk, Samara, and Orenburg Oblasts, the Mari El, Udmurt, and Chuvash Republics, and the Republic of Bashkortostan. The area of the republic is 68,000 square kilometres (26,000 sq mi). The unofficial Tatarstan motto is Bez Buldırabız! (We can!).[16] As of the 2010 Census, the population of Tatarstan was 3,786,488.[9]

The state has strong cultural ties with its eastern neighbor, the Republic of Bashkortostan.[17][18]

The state languages of the Republic of Tatarstan are Tatar and Russian.

Etymology

"Tatarstan" derives from the name of the ethnic group—the Tatars—and the Persian suffix -stan (meaning "state" or "country" of, an ending common to many Eurasian countries). Another version of the Russian name is "Тата́рия" (Tatariya), which was official along with "Tatar ASSR" during Soviet rule.

Geography

The republic is located in the center of the East European Plain, approximately 800 kilometers (500 mi) east of Moscow. It lies between the Volga River and the Kama River (a tributary of the Volga), and extends east to the Ural mountains.

- Borders:

- internal: Kirov Oblast (N), Udmurt Republic (N/NE), Republic of Bashkortostan (E/SE), Orenburg Oblast (SE), Samara Oblast (S), Ulyanovsk Oblast (S/SW), Chuvash Republic (W), Mari El Republic (W/NW).

- Highest point: 381 m (1,250 ft)[19]

- Maximum N–S distance: 290 km (180 mi)

- Maximum E–W distance: 460 km (290 mi)

Rivers

Major rivers include (Tatar names are given in parentheses):

- Azevka River (Äzi)

- Belaya River (Ağidel)

- Ik River (Iq)

- Kama River (Çulman)

- Volga River (İdel)

- Vyatka River (Noqrat)

- Kazanka River (Qazansu)

- Zay River (Zäy)

Lakes

Major reservoirs of the republic include (Tatar names are given in parentheses):

- Kuybyshev Reservoir (Kuybışev)

- Lower Kama Reservoir (Tübän Kama)

- Zainsk Reservoir (Zäy susaqlağıçı)

Hills

- Bugulma-Belebey Upland

- Volga Upland

- Vyatskie Uvaly

Natural resources

Major natural resources of Tatarstan include oil, natural gas, gypsum, and more. It is estimated that the Republic has over one billion tons of oil deposits.[20]

Climate

- Average January temperature: −15 °C (5 °F)

- Average July temperature: +18 °C (64 °F)

- Average annual temperature: +4 °C (39 °F)

- Average annual precipitation: up to 500 to 550 mm (20 to 22 in)

Administrative divisions

Administrative and territorial division: 43 municipal districts and 2 urban districts (Kazan and Naberezhnye Chelny), as well as 39 urban settlements and 872 rural settlements. The Republic of Tatarstan consists of districts and cities of republican significance, the list of which is established by the Constitution of the Republic of Tatarstan. The districts consist of cities of district significance, urban-type settlements and rural settlements with subordinate territories that make up the primary level in the system of administrative-territorial structure of the Republic. Cities of national significance can be geographically divided into districts in the city.

History

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Tatarstan |

|

Middle Ages

The earliest known organized state within the boundaries of Tatarstan was Volga Bulgaria (c. 700–1238). The Volga Bulgars had an advanced mercantile state with trade contacts throughout Inner Eurasia, the Middle East, and the Baltic, which maintained its independence despite pressure by such nations as the Khazars, the Kievan Rus, and the Cuman-Kipchaks. Islam was introduced by missionaries from Baghdad around the time of Ibn Fadlan's journey in 922.

Volga Bulgaria finally fell to the armies of the Mongol prince Batu Khan in the late 1230s (see Mongol invasion of Volga Bulgaria). The inhabitants, mixing with the Golden Horde's Kipchak-speaking people, became known as the "Volga Tatars". Another theory postulates that there were no ethnic changes in that period, and Bulgars simply switched to the Kipchak-based Tatar language. In the 1430s, the region again became independent as the base of the Khanate of Kazan, a capital having been established in Kazan, 170 km (110 mi) up the Volga from the ruined capital of the Bulgars.

The Khanate of Kazan was conquered by the troops of Tsar Ivan the Terrible in the 1550s, with Kazan being taken in 1552. A large number of Bulgars were killed and forcibly converted to Christianity and were culturally Russified. Cathedrals were built in Kazan; by 1593 all mosques in the area were destroyed. The Russian government forbade the construction of mosques, a prohibition that was not lifted until the 18th century by Catherine the Great. The first mosque to be rebuilt under Catherine's auspices was constructed in 1766–1770.

19th century

In the 19th century, Tatarstan became a center of Jadidism, an Islamic movement that preached tolerance of other religions. Under the influence of local Jadidist theologians, the Bulgars were renowned for their friendly relations with other peoples of the Russian Empire. However, after the October Revolution religion was largely outlawed and all theologians were repressed.

Early 20th century

During the Civil War of 1918–1920 Tatar nationalists attempted to establish an independent republic (the Idel-Ural State). They were, however, put down by the Bolsheviks and the Tatar Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was established on May 27, 1920.[4] The boundaries of the republic did not include a majority of the Volga Tatars. The Tatar Union of the Godless were persecuted in Stalin's 1928 purges.

1921–1922 famine

There was a famine in the Tatar Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic in 1921 to 1922 as a result of war communist policy. The famine deaths of 2,000,000 Tatars in Tatar ASSR and in Volga-Ural region in 1921–1922 was catastrophic as half of Volga Tatar population in USSR died. This famine is also known as "terror-famine" and "famine-genocide" in Tatarstan.[21] The Soviets settled ethnic Russians after the famine in Tatar ASSR and in Volga-Ural region causing the Tatar share of the population to decline to less than 50%. The All-Russian Tatar Social Center (VTOTs) has asked the United Nations to condemn the 1921 Tatarstan famine as Genocide of Muslim Tatars.[22] The 1921–1922 famine in Tatarstan has been compared to the Holodomor in Ukraine.[23]

Modern times

On August 30, 1990, Tatarstan announced its sovereignty with the Declaration on the State Sovereignty of the Tatar Soviet Socialist Republic[24] and in 1992 Tatarstan held a referendum on the new constitution.[25] Some 62% of those who took part voted in favor of the constitution. In the 1992 Tatarstan Constitution, Tatarstan is defined as a Sovereign State. However, the referendum and constitution were declared unconstitutional by the Russian Constitutional Court.[26] Articles 1 and 3 of the Constitution as introduced in 2002[25] define Tatarstan as a part of the Russian Federation.

On February 15, 1994, the Treaty On Delimitation of Jurisdictional Subjects and Mutual Delegation of Authority between the State Bodies of the Russian Federation and the State Bodies of the Republic of Tatarstan[27] and Agreement between the Government of the Russian Federation and the Government of the Republic of Tatarstan (On Delimitation of Authority in the Sphere of Foreign Economic Relations) were signed. The power-sharing agreement was renewed on July 11, 2007, though with much of the power delegated to Tatarstan reduced.[28]

On December 20, 2008, in response to Russia recognizing Abkhazia and South Ossetia, the Milli Mejlis of the Tatar People declared Tatarstan independent and asked for United Nations recognition.[29] However, this declaration was ignored both by the United Nations and the Russian government. On July 24, 2017, the autonomy agreement signed in 1994 between Moscow and Kazan expired, making Tatarstan the last republic of Russia to lose its special status.[30]

Demographics

Population: 3,786,488 (2010 Census);[9] 3,779,265 (2002 Census);[31] 3,637,809 (1989 Census).[32]

Settlements

Vital statistics

| Average population (1000s) | Live births | Deaths | Natural change | Crude birth rate (per 1000) | Crude death rate (per 1000) | Natural change (per 1000) | Fertility rates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 3,146 | 47,817 | 25,622 | 22,195 | 15.2 | 8.1 | 7.1 | |

| 1975 | 3,311 | 55,095 | 29,686 | 25,409 | 16.6 | 9.0 | 7.7 | |

| 1980 | 3,465 | 54,272 | 32,758 | 21,514 | 15.7 | 9.5 | 6.2 | |

| 1985 | 3,530 | 64,067 | 34,622 | 29,445 | 18.1 | 9.8 | 8.3 | |

| 1990 | 3,665 | 56,277 | 36,219 | 20,058 | 15.4 | 9.9 | 5.5 | 2.05 |

| 1991 | 3,684 | 50,160 | 37,266 | 12,894 | 13.6 | 10.1 | 3.5 | 1.88 |

| 1992 | 3,706 | 44,990 | 39,148 | 5,842 | 12.1 | 10.6 | 1.6 | 1.71 |

| 1993 | 3,730 | 41,144 | 44,291 | −3,147 | 11.0 | 11.9 | −0.8 | 1.57 |

| 1994 | 3,746 | 41,811 | 48,613 | −6,802 | 11.2 | 13.0 | −1.8 | 1.58 |

| 1995 | 3,756 | 39,070 | 48,592 | −9,522 | 10.4 | 12.9 | −2.5 | 1.47 |

| 1996 | 3,766 | 38,080 | 45,731 | −7,651 | 10.1 | 12.1 | −2.0 | 1.43 |

| 1997 | 3,775 | 37,268 | 46,270 | −9,002 | 9.9 | 12.3 | −2.4 | 1.38 |

| 1998 | 3,785 | 37,182 | 45,153 | −7,971 | 9.8 | 11.9 | −2.1 | 1.37 |

| 1999 | 3,789 | 35,073 | 46,679 | −11,606 | 9.3 | 12.3 | −3.1 | 1.29 |

| 2000 | 3,788 | 35,446 | 49,723 | −14,277 | 9.4 | 13.1 | −3.8 | 1.29 |

| 2001 | 3,784 | 35,877 | 50,119 | −14,242 | 9.5 | 13.2 | −3.8 | 1.30 |

| 2002 | 3,779 | 38,178 | 51,685 | −13,507 | 10.1 | 13.7 | −3.6 | 1.37 |

| 2003 | 3,775 | 38,461 | 52,263 | −13,802 | 10.2 | 13.8 | −3.7 | 1.36 |

| 2004 | 3,771 | 38,661 | 51,322 | −12,661 | 10.3 | 13.6 | −3.4 | 1.34 |

| 2005 | 3,767 | 36,967 | 51,841 | −14,874 | 9.8 | 13.8 | −3.9 | 1.26 |

| 2006 | 3,763 | 37,303 | 49,218 | −11,915 | 9.9 | 13.1 | −3.2 | 1.25 |

| 2007 | 3,763 | 40,892 | 48,962 | −8,070 | 10.9 | 13.0 | −2.1 | 1.36 |

| 2008 | 3,772 | 44,290 | 48,952 | −4,662 | 11.8 | 13.0 | −1.2 | 1.45 |

| 2009 | 3,779 | 46,605 | 47,892 | −1,287 | 12.4 | 12.7 | −0.3 | 1.55 |

| 2010 | 3,785 | 48,968 | 49,730 | −762 | 12.9 | 13.1 | −0.2 | 1.60 |

| 2011 | 3,795 | 50,824 | 47,072 | 3,752 | 13.4 | 12.4 | 1.0 | 1.65 |

| 2012 | 3,813 | 55,421 | 46,358 | 9,063 | 14.5 | 12.2 | 2.3 | 1.80 |

| 2013 | 3,830 | 56,458 | 46,192 | 10,266 | 14.7 | 12.1 | 2.6 | 1.83 |

| 2014 | 3,847 | 56,480 | 46,921 | 9,559 | 14.7 | 12.2 | 2.5 | 1.84 |

| 2015 | 3,862 | 56,899 | 46,483 | 10,416 | 14.7 | 12.0 | 2.7 | 1.86 |

| 2016 | 3,878 | 55,853 | 44,894 | 10,959 | 14.4 | 11.6 | 2.8 | 1.86 (est) |

| 2017 | 3,889 | 48,115 | 43,957 | 4,158 | 12.4 | 11.3 | 1.1 | |

| 2018 | 3,894 | 46,320 | 44,720 | 1,600 | 11.9 | 11.5 | 0.4 | |

| 2019 | 42,871 | 42,691 | 180 | 11.0 | 11.0 | 0.0 |

Note: TFR source.[34]

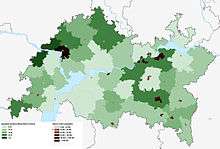

Ethnic groups

| Ethnic group |

1926 Census | 1939 Census | 1959 Census | 1970 Census | 1979 Census | 1989 Census | 2002 Census | 2010 Census1[9] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Tatars | 1,263,383 | 48.7% | 1,421,514 | 48.8% | 1,345,195 | 47.2% | 1,536,430 | 49.1% | 1,641,603 | 47.6% | 1,765,404 | 48.5% | 2,000,116 | 52.9% | 2,012,571 | 53.2% |

| Russians | 1,118,834 | 43.1% | 1,250,667 | 42.9% | 1,252,413 | 43.9% | 1,382,738 | 42.4% | 1,516,023 | 44.0% | 1,575,361 | 43.3% | 1,492,602 | 39.5% | 1,501,369 | 39.7% |

| Chuvash | 127,330 | 4.9% | 138,935 | 4.8% | 143,552 | 5.0% | 153,496 | 4.9% | 147,088 | 4.3% | 134,221 | 3.7% | 126,532 | 3.3% | 116,252 | 3.1% |

| Others | 84,485 | 3.3% | 104,161 | 3.6% | 109,257 | 3.8% | 112,574 | 3.6% | 140,698 | 4.1% | 166,756 | 4.6% | 160,015 | 4.2% | 150,244 | 4.1% |

| 1 6,052 people were registered from administrative databases, and could not declare an ethnicity. It is estimated that the proportion of ethnicities in this group is the same as that of the declared group.[35] | ||||||||||||||||

There are about 2 million ethnic Tatars and 1.5 million ethnic Russians, along with significant numbers of Chuvash, Mari, and Udmurts, some of whom are Tatar-speaking. The Ukrainian, Mordvin, and Bashkir minorities are also significant. Most Tatars are Sunni Muslims, but a small minority known as Keräşen Tatars are Orthodox and some of them regard themselves as being different from other Tatars even though most Keräşen dialects differ only slightly from the Central Dialect of the Tatar language.[36]

There is a fair degree of speculation as to the early origins of the different groups of Tatars, but most Tatars no longer view religious identity as being as important as it once was, and the religious and linguistic subgroups have intermingled considerably. Nevertheless, despite many decades of assimilation and intermingling, some Keräşen demanded and were awarded the option of being specifically enumerated in 2002. This has provoked great controversy, however, as many intellectuals have sought to portray the Tatars as homogeneous and indivisible.[37] Although listed separately below, the Keräşen are still included in the grand total for the Tatars. Another unique ethnic group, concentrated in Tatarstan, is the Qaratay Mordvins.

Jews in Tatarstan

Tatar and Udmurt Jews are special territorial groups of the Ashkenazi Jews, which started to be formed in the residential areas of mixed Turkic-speaking (Tatars, Kryashens, Bashkirs, Chuvash people), Finno-Ugric-speaking (Udmurts, Mari people) and Slavic-speaking (Russians) population. The Ashkenazi Jews on the territory of Tatarstan first appeared in the 1830s.[38] The Jews of Udmurtia and Tatarstan are subdivided on cultural and linguistic characteristics into two territorial groups: 1) Udmurt Jews (Udmurt Jewry), who lived on the territory of Udmurtia and the north of Tatarstan; 2) Tatar Jews or Kazan Jews (Tatar Jewry or Kazan Jewry), who lived mainly in the city of Kazan and its agglomeration.[39]

Languages

In accordance with the Constitution of the Republic of Tatarstan, the two state languages of the republic are Tatar and Russian. According to the 2002 Russian Federal Law (On Languages of Peoples of the Russian Federation), the official script is Cyrillic. Linguistic anthropologist Dr. Suzanne Wertheim, notes that "some men signal ideological devotion to the Tatar cause by refusing to accommodate to Russian-dominant public space or Russian speakers", whilst women, in promoting "the Tatar state and Tatar national culture, index their pro-Tatar ideological stances more diplomatically, and with linguistic practices situated only within the Tatar-speaking community ... in keeping with normative gender roles within the Tatar republic."[40]

Religion

Established in 922, the first Muslim state within the boundaries of modern Russia was Volga Bulgaria from which the Tatars inherited Islam. Islam was introduced by missionaries[43] from Baghdad around the time of Ibn Fadlan's journey in 922. Islam's long presence in Russia also extends at least as far back as the conquest of the Khanate of Kazan in 1552, which brought the Tatars and Bashkirs on the Middle Volga into Russia.

In the 1430s, the region became independent as the base of the Khanate of Kazan, a capital having been established in Kazan, 170 km up the Volga from the ruined capital of the Bulgars. The Khanate of Kazan was conquered by the troops of Tsar Ivan IV the Terrible in the 1550s, with Kazan being taken in 1552. Some Tatars were forcibly converted to Christianity and cathedrals were built in Kazan; by 1593, mosques in the area were destroyed. The Russian government forbade the construction of mosques, a prohibition that was not lifted until the 18th century by Catherine II.

When it comes to religion, Islam is the most common faith in Tatarstan, as, 48.8% of the estimated 3.8 million population is Muslim while the remaining population is mostly Russian Orthodox Christian and non-religious.[44]

In 1990, there were only 100 mosques but the number, as of 2004, rose to well over 1,000. As of January 1, 2008, as many as 1,398 religious organizations were registered in Tatarstan, of which 1,055 were Muslim. Islam is the most common faith in Tatarstan, as, according one study, 38.8% of the population is Muslim.[45] In September 2010, Eid al-Fitr as well May 21, the day the Volga Bulgars embraced Islam, were made public holidays.[46] Tatarstan also hosted an international Muslim film festival which screened over 70 films from 28 countries including Jordan, Afghanistan, and Egypt.[47]

The Russian Orthodox Church is the second largest active religion in Tatarstan, and has been so for more than 150 years,[48] with an estimated 1.6 million followers made up of ethnic Russians, Mordvins, Armenians, Belarusians, Mari people, Georgians, Chuvash and a number of Orthodox Tatars which together constitute 45% of the 3.8 million population of Tatarstan. On 23 August 2010, the "Orthodox monuments of Tatarstan" exhibition was held in Kazan by the Tatarstan Ministry of Culture and the Kazan Eparchy.[49] At all public events, an Orthodox Priest is called upon along with an Islamic Mufti.[50]

The Muslim Religious Board of Tatarstan frequently organizes activities, like the 'Islamic graffiti Contest' which was held on November 20, 2011.[51]

Politics

The head of the government in Tatarstan is the President. Since March 2010, the President has been Rustam Minnikhanov.[52] Tatarstan's unicameral State Council has 100 seats: fifty are for representatives of the parties, and the other fifty are for deputies from the republic's localities. The Chairman of the State Council is Farit Mukhametshin since May 27, 1998. The government is the Сabinet of Ministers. The Prime Minister of the Republic of Tatarstan is Alexei Pesoshin.

According to the Constitution of the Republic of Tatarstan, the President can be elected only by the people of Tatarstan, but due to Russian federal law, this law was suspended for an indefinite term. The Russian law on the election of governors says they should be elected by regional parliaments and that the candidate can be presented only by the president of Russia.

On March 25, 2005 Shaymiyev was re-elected for his fourth term by the State Council. This election was held after changes in electoral law and does not contradict the Constitutions of Tatarstan and Russia.

Political status

.jpg)

The Republic of Tatarstan is a constituent republic of the Russian Federation. Most of the Russian federal subjects are tied with the Russian federal government by the uniform Federal Treaty, but relations between the government of Tatarstan and the Russian federal government are more complex and are precisely defined in the Constitution of the Republic of Tatarstan. The following passage from the Constitution defines the republic's status without contradicting the Constitution of the Russian Federation:

"The Republic of Tatarstan is a democratic constitutional State associated with the Russian Federation by the Constitution of the Russian Federation, the Constitution of the Republic of Tatarstan and the Treaty between the Russian Federation and the Republic of Tatarstan On Delimitation of Jurisdictional Subjects and Mutual Delegation of Powers between the State Bodies of the Russian Federation and the State Bodies of the Republic of Tatarstan, and a subject of the Russian Federation. The sovereignty of the Republic of Tatarstan shall consist in full possession of the State authority (legislative, executive and judicial) beyond the competence of the Russian Federation and powers of the Russian Federation in the sphere of shared competence of the Russian Federation and the Republic of Tatarstan and shall be an inalienable qualitative status of the Republic of Tatarstan."[53]

Economy

Tatarstan is one of the most economically developed regions of Russia. The republic is highly industrialized and ranks second to Samara Oblast in terms of industrial production per km2.[54] in 2017 Tatarstan's GDP per capita was $10,000,[55] with total GDP at about $35 billion.[56]

The region's main source of wealth is oil. Tatarstan produces 32 million tonnes of crude oil per year and has estimated oil reserves of more than 1 billion tons.[20][57] Industrial production constitutes 45% of the Republic's gross regional domestic product. The most developed manufacturing industries are petrochemical industry and machine building. The truck-maker KamAZ is the region's largest enterprise and employs about one-fifth of Tatarstan's workforce.[57] Kazanorgsintez, based in Kazan, is one of Russia's largest chemical companies.[58] Tatarstan's aviation industry produces Tu-214 passenger airplanes and helicopters.[20] The Kazan Helicopter Plant is one of the largest helicopter manufacturers in the world.[59] Engineering, textiles, clothing, wood processing, and food industries are also of key significance in Tatarstan.[54]

Tatarstan consists of three distinct industrial regions. The northwestern part is an old industrial region where engineering, chemical, and light industry dominate. In the newly industrial northeast region with its core in the Naberezhnye Chelny–Nizhnekamsk agglomeration, major industries are automobile construction, the chemical industry, and power engineering. The southeast region has oil production with engineering under development. The north, central, south, and southwest parts of the republic are rural regions.[60] The republic has huge water resources—the annual flow of rivers of the Republic exceeds 240 billion m3 (8.5 trillion cu ft). Soils are very diverse, the best fertile soils covering one-third of the territory. Due to the high development of agriculture in Tatarstan (it contributes 5.1% of the total revenue of the republic), forests occupy only 16% of its territory. The agricultural sector of the economy is represented mostly by large companies as "Ak Bars Holding" and "Krasniy Vostok Agro".

The republic has a highly developed transport network. It mainly comprises highways, railway lines, four navigable rivers — Volga (İdel), Kama (Çulman), Vyatka (Noqrat) and Belaya (Ağidel), and oil pipelines and airlines. The territory of Tatarstan is crossed by the main gas pipelines carrying natural gas from Urengoy and Yamburg to the west and the major oil pipelines supplying oil to various cities in the European part of Russia.

Tourism

There are three UNESCO world heritage sites in Tatarstan-Kazan Kremlin, Bulgarian state Museum-reserve and assumption Cathedral and Monastery of the town-island of Sviyazhsk.[61]

The annual growth rate of tourist flow to the republic is on average 13.5%, the growth rate of the volume of services in the tourism sector is 17.0%.[62]

At the end of 2016 on the territory of the Republic of Tatarstan there were 104 tour operators, of which 32 dealt in domestic tourism, 65 in domestic and inbound tourism, 1 in domestic and outbound tourism, and 6 in all three.

As of January 1, 2017, 404 collective accommodation facilities (CSR) operate in the Republic of Tatarstan, 379 CSR are subject to classification (183 in Kazan, 196 in other municipalities of the Republic of Tatarstan).[63] 334 collective accommodation facilities received the certificate of assignment of the category, which is 88.1% of the total number of operating.

In 2016, special attention was paid to the development of tourist centers of the Republic of Tatarstan – Kazan, Bolghar, the town-island of Sviyazhsk, Yelabuga, Chistopol, Tetyushi. The growth of tourist flow in the main tourist centers of the Republic compared to 2015 amounted to an average of 45.9%.

Currently, sanatorium and resort recreation is developing rapidly in Tatarstan. There are 46 sanatorium-resort institutions in the Republic of Tatarstan. The capacity of the objects of the sanatorium-resort complex of Tatarstan is 8847 beds, more than 4300 specialists are engaged in the service of residents. In 2016, more than 160 thousand people rested in the health resorts of the Republic of Tatarstan.[64] 22 health resort institutions of the Republic of Tatarstan are members of the Association of health resort institutions "Health resorts of Tatarstan", including 11 sanatoriums of PJSC "Tatneft".

Since 2016, the Republic of Tatarstan has been operating the Visit Tatarstan program – the official tourism brand of the Republic, the purpose of which is to inform tourists, monitor the reputation of the Republic, develop the tourism potential of the regions of Tatarstan, conduct market research, partner projects with local companies and international expansion. Tatarstan: 1001 pleasure-the main message that tourists receive. The Visit Tatar website, where there is information about the main sights and recreation in Tatarstan, is available in 8 languages: Tatar, Russian, English, Chinese, German, Spanish, Finnish and Persian.[65][66]

Tourist resources of historical and cultural significance

- Kazan Kremlin

- Kazan University

- Bolghar

- Sviyazhsk

- Temple of All Religions

- Qolşärif Mosque

- Saints Peter and Paul Cathedral

- Söyembikä Tower

- Millennium Bridge

- Old Tatar Quarter

- Galiaskar Kamal Tatar Academic Theatre

- The Jalil Opera and Ballet Theatre

- The National Museum of Tatarstan

Culture

Major libraries include Kazan State University Nikolai Lobachevsky Scientific Library and the National Library of the Republic of Tatarstan. There are two museums of republican significance, as well as 90 museums of local importance. In the past several years, new museums appeared throughout the Republic.

There are twelve theatrical institutions in Tatarstan.[67] The state orchestra is the National Tatarstan Orchestra.

In 1996, the Tatar singer, Guzel Ahmetova, cooperated with the German Eurodance group named Snap!, when she sang the lyrics of the song "Rame".[68][69]

Sports

Tatarstan has Rubin Kazan, a major European football team which has played in the UEFA Champions League and the UEFA Europa League. Twice Russian champions, Rubin Kazan play in the Russian Premier League. Also, Tatarstan has Unics Kazan which has gained a significant role in European basketball, playing in Euroleague and EuroCup for decades.

It also has two KHL teams, the successful Ak Bars Kazan, which is based in the capital city of Kazan, and the Neftekhimik Nizhnekamsk, who play in the city of Nizhnekamsk. The state also has a Russian Major League team (the second highest hockey league in Russia), Neftyanik Almetyevsk, who play in the city of Almetyevsk. There are also two Minor Hockey League teams which serve as affiliates for the two KHL teams. A team also exists in the Russian Hockey League, the HC Chelny, which is based in the city of Naberezhnye Chelny. Another team plays in the MHL-B (the second level of junior ice hockey in Russia).

Nail Yakupov is an ethnic Tatar who was drafted first overall in the 2012 NHL Entry Draft.

Former ATP No.1 Marat Safin and former WTA number 1 Dinara Safina are of Tatar descent.

Kazan hosted the XXVII Summer Universiade in 2013. Kazan also hosted the FINA World championship in aquatic sports in August 2015.

Education

The most important facilities of higher education include Kazan State University, Kazan State Medical University, Kazan State Technological University, World Information Distributed University, Kazan State Technical University, Kazan State Finance and Economics Institute and Russian Islamic University, all located in the capital Kazan.

Public spaces

Tatarstan takes a unique participatory approach to the development of public spaces that has earned it recognition. The Tatarstan Public Spaces Development Programme aims to create spaces for meeting or recreation.[70] The programme covers a wide spectrum of projects, including streets, squares, parks, river banks, pavilions, and sports facilities.[70]

Since 2016[70] (and continuing until 2022), the Architecturny Desant Architectural Bureau in Kazan[71] is improving public spaces in each of Tatarstan's 45 municipal districts, from large cities to small villages.[72] As of April 2019, the project had revamped 328 public spaces.[73] By creating and rehabilitating public spaces, the programme aims to be a catalyst for positive social, economic, and environmental change.[74]

One notable example is the "Beach" at Almetyevsk, which includes public swimming pools and a terrace.[70] Other examples include an amphitheatre in Black Lake Park, Kazan; the Central Square in Bavly; a children's playground in Bogatye Saby village, which has a unique wooden play structure; the Cube container centre in the green beach at Gorkinsko-Ometievsky forest, Kazan; and the square on Festival Boulevard, Kazan.[74]

The programme used an innovative participatory design approach,[75] which later became mandatory for similar projects across Russia.[74] This approach partners specialists with local residents at every stage of the project, from development, to implementation, to the ongoing use of the space.[75]

The Tatarstan Public Spaces Development Programme was announced as one of the six winners of the 2019 Aga Khan Award for Architecture.[76][77][78] The jury was impressed by the programme's systematic approach and involvement of residents to decide the future of each space.[75][79]

Each public space expresses the unique identity of that particular place,[74] tying in its history while incorporating traditional materials.[75] Major goals of the projects include improving the quality of life for residents and improving the environment.[75] The Arhitekturnyi Desant team aims to provide a high quality public space, no matter the size of the settlement, including quality design, infrastructure, and materials.[75]

Spending on the public spaces projects is helping the local economy.[70] For example, the number of street furniture manufacturers in the area increased from 12 to 75 since the programme started.[70]

See also

- Volga Tatars

- List of Chairmen of the State Council of Tatarstan

- List of rural localities in Tatarstan

- 1921–22 famine in Tatarstan

- List of Tatars

- Music of Tatarstan

References

- Law #2284, Chapter III

- Президент Российской Федерации. Указ №849 от 13 мая 2000 г. «О полномочном представителе Президента Российской Федерации в федеральном округе». Вступил в силу 13 мая 2000 г. Опубликован: "Собрание законодательства РФ", No. 20, ст. 2112, 15 мая 2000 г. (President of the Russian Federation. Decree #849 of May 13, 2000 On the Plenipotentiary Representative of the President of the Russian Federation in a Federal District. Effective as of May 13, 2000.).

- Госстандарт Российской Федерации. №ОК 024-95 27 декабря 1995 г. «Общероссийский классификатор экономических регионов. 2. Экономические районы», в ред. Изменения №5/2001 ОКЭР. (Gosstandart of the Russian Federation. #OK 024-95 December 27, 1995 Russian Classification of Economic Regions. 2. Economic Regions, as amended by the Amendment #5/2001 OKER. ).

- Administrative-Territorial Structure of the Republic of Tatarstan, p. 3

- Constitution of the Republic of Tatarstan, Article 122

- Constitution of the Republic of Tatarstan, Article 9.2

- "Biography : Rustam Minnikhanov". President.tatar.ru. Archived from the original on January 1, 2017. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- Федеральная служба государственной статистики (Federal State Statistics Service) (May 21, 2004). "Территория, число районов, населённых пунктов и сельских администраций по субъектам Российской Федерации (Territory, Number of Districts, Inhabited Localities, and Rural Administration by Federal Subjects of the Russian Federation)". Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года (All-Russia Population Census of 2002) (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1" [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года [2010 All-Russia Population Census] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- "26. Численность постоянного населения Российской Федерации по муниципальным образованиям на 1 января 2018 года". Federal State Statistics Service. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- "Об исчислении времени". Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). June 3, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- Official throughout the Russian Federation according to Article 68.1 of the Constitution of Russia.

- Constitution of the Republic of Tatarstan, Article 8.1

- Daniel R. Kempton and Terry D. Clark. Unity or Separation: Center-Periphery Relations in the Former Soviet Union. Praeger Publishers, 2002, p. 110.

- Tatarstan

- "Татарстан Республикасы Президенты Шәймиев Минтимер Шәрип улы. Рәсми сервер". June 18, 2008. Archived from the original on June 18, 2008.

- "Tatarstan And Bashkortostan Become More Close". Executive Committee of World Congress of Tatars. December 23, 2010. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012.

- "Meeting of two presidents". Administration of President of the Republic Tatarstan. August 16, 2011. Archived from the original on January 8, 2014. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

- "Geographical Location". tatarstan.ru. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- "Economy : The Republic of Tatarstan". September 24, 2006. Archived from the original on September 24, 2006.

- Mizelle, Peter Christopher (2002). "Battle with Famine": Soviet Relief and the Tatar Republic 1921–1922. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- "Tatar Nationalists Ask UN to Condemn 1921 Famine as Genocide | MariUver". Mariuveren.wordpress.com. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- "Seven million died in the 'forgotten' holocaust – Eric Margolis". Ukemonde.com. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- "Declaration on the State Sovereignty of the Republic of Tatarstan". January 19, 2000. Archived from the original on January 19, 2000.

- "Конституция Республики Татарстан : Республика Татарстан". September 25, 2006. Archived from the original on September 25, 2006.

- "Заявились в Россию :: Общество :: Газета РБК". Rbcdaily.ru. March 17, 2014. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- "The Republic Of Tatarstan:TREATY BETWEEN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION AND THE REPUBLIC OF TATARSTAN On Delimitation of Jurisdictional Subjects and Mutual Delegation of Authority between the State Bodies of the Russian Federation and the State Bodies of the Republic of Tatarstan". April 28, 1999. Archived from the original on April 28, 1999.

- "Federation Council Backs Power-Sharing Bill". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. July 11, 2007. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- Smirnova, Lena (July 24, 2017). "Tatarstan, the Last Region to Lose Its Special Status Under Putin". The Moscow Times. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (May 21, 2004). "Численность населения России, субъектов Российской Федерации в составе федеральных округов, районов, городских поселений, сельских населённых пунктов – районных центров и сельских населённых пунктов с населением 3 тысячи и более человек" [Population of Russia, Its Federal Districts, Federal Subjects, Districts, Urban Localities, Rural Localities—Administrative Centers, and Rural Localities with Population of Over 3,000] (XLS). Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года [All-Russia Population Census of 2002] (in Russian).

- "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 г. Численность наличного населения союзных и автономных республик, автономных областей и округов, краёв, областей, районов, городских поселений и сёл-райцентров" [All Union Population Census of 1989: Present Population of Union and Autonomous Republics, Autonomous Oblasts and Okrugs, Krais, Oblasts, Districts, Urban Settlements, and Villages Serving as District Administrative Centers]. Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года [All-Union Population Census of 1989] (in Russian). Институт демографии Национального исследовательского университета: Высшая школа экономики [Institute of Demography at the National Research University: Higher School of Economics]. 1989 – via Demoscope Weekly.

- "п≤п╫я┌п╣я─п╟п╨я┌п╦п╡п╫п╟я▐ п╡п╦я┌я─п╦п╫п╟". Gks.ru. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- "Каталог публикаций::Федеральная служба государственной статистики". Gks.ru. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- "ВПН-2010". Perepis-2010.ru. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- "Tatar The language of the largest minority in Russia". American Association of Teachers of Turkic. Archived from the original on December 13, 2006. Retrieved March 10, 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Tatars as Meso-Nation" (PDF). Hokkaido University. Retrieved March 10, 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Казань. Электронная еврейская энциклопедия". Eleven.co.il. April 15, 2005. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- Altyntsev A.V., "The Concept of Love in Ashkenazim of Udmurtia and Tatarstan", Nauka Udmurtii. 2013. No. 4 (66), p. 131. (Алтынцев А.В., "Чувство любви в понимании евреев-ашкенази Удмуртии и Татарстана". Наука Удмуртии. 2013. №4. С. 131: Комментарии.) (in Russian)

- Wertheim, Suzanne (September 2012). "Gender, nationalism, and the attempted reconfiguration of sociolinguistic norms". Gender and Language. 6 (2): 261–289. doi:10.1558/genl.v6i2.261.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Arena: Atlas of Religions and Nationalities in Russia". Sreda, 2012.

- 2012 Arena Atlas Religion Maps. "Ogonek", № 34 (5243), 27/08/2012. Retrieved 21/04/2017. Archived.

- "Tatarstan Parliament Introduces New Islam Holiday". Rferl.org. September 24, 2010. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- Balkind, Nicole (2009). A Model Republic? Trust and Authoritarianism on Tatarstan's Road to Autonomy (MA).

- Alexey D. Krindatch. Patterns of Religious Change in Postsoviet Russia: Major Trends from 1998 to 2003. Religion, State & Society, Vol. 32, No. 2, June 2004. Published by BiblicalStudies.org.uk, p. 123.

- "Holiday Commemorating Arrival of Islam in Russia Ratified in Tatarstan". Islam Today. September 25, 2010. Archived from the original on September 30, 2010. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- "Tatarstan's Muslim filmfest kicks off". September 16, 2010. Archived from the original on September 18, 2010.

- "Religion in Tatarstan".

- ""Orthodox monuments of Tatarstan" exhibition to be held in Kazan". Eng.tatar-inform.ru. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- "Today's Tatarstan in brief". September 30, 2000. Archived from the original on September 30, 2000.

- Valeev, Denis (November 22, 2011). "Islamic Graffiti Contest Held In Kazan". The Kazan Times. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- "Tatarstan's New President Sworn In". Rferl.org. March 25, 2010. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- "KCFPP: The Constitution of the Republic of Tatarstan – New redaction of the Constitution of the Republic of Tatarstan of the 19th of April, 2002". Kazanfed.ru. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- "Tatarstan". Encarta. Archived from the original on November 1, 2009. Retrieved April 15, 2009.

- "Human Development Index in the Regions of Russia" (PDF). Human Development Report 2006/2007 for the Russian Federation (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 10, 2010. Retrieved April 24, 2009.

- "Валовой региональный продукт::Мордовиястат". mrd.gks.ru. Archived from the original on February 17, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- "TATARSTAN - Economy". April 24, 2001. Archived from the original on April 24, 2001.

- lor08 (February 18, 2016). "ПАО "Казаньоргсинтез"". Kazanorgsintez.ru. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- "Kazan Helicopter Plant (KHP) - Russian Defense Industry". January 13, 2001. Archived from the original on January 13, 2001.

- Pirkko Suihkonen. "Call for papers: LENCA-2". Ling.helsinki.fi. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- "В Татарстане три исторических объекта признаны мировым достоянием" (Казанские Ведомости ed.). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - http://tourism.tatarstan.ru/rus/file/pub/pub_857409.pdf Archived December 15, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Данные Государственного комитета Республики Татарстан по туризму за 2016 год

- "Государственный комитет Республики Татарстан по туризму" (in Russian). tourism.tatarstan.ru. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- "Программа "Отдыхай в Татарстане" поможет развитию санаторных курортов" (РИА НОВОСТИ ed.). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Разработка программы Visit Tatarstan обошлась в 2 млн. рублей". БИЗНЕС Online (in Russian). Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- "Официальный туристический портал Республики Татарстан". visit-tatarstan.com. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- "Culture : The Republic of Tatarstan". September 24, 2006. Archived from the original on September 24, 2006.

- "Snap! – Rame".

- "Snap! – Rame (Гузель Ахметова Cover)".

- "Aga-Khan-Award: Die Plätze dem Volk in Tatarstan". Baublatt (in German). Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- GmbH, BauNetz Media (May 6, 2019). "Von Kinderdorf bis Fischmarkt - Shortlist des Aga Khan Award 2019". BauNetz (in German). Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- "Shortlist for the 2019 Aga Khan Award for Architecture announced". Architectural Digest Middle East. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- "Three UAE Projects on 2019 shortlist for Aga Khan Award for Architecture". gulfnews.com. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- "Tatarstan Public Spaces Development Programme". www.akdn.org. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- "Программа развития общественных пространств в Татарстане поразила жюри премии Ага Хана системностью". www.tatar-inform.ru (in Russian). Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- Woodyatt, Amy (August 29, 2019). "Winners of prestigious Aga Khan architecture award announced". CNN Style. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- "ТОП-10 значимых событий в Татарстане за прошедшее 10-летие". sntat.ru (in Russian). Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- "In Tatarstan, Russia, a Parks Program Creates Over 350 Public Spaces". Metropolis. January 21, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- Pitcher, Greg. "Two London practices shortlisted for Aga Khan Award". Architects Journal. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

Sources

- Закон №2284 от 14 июля 1999 г. «О государственных символах Республики Татарстан», в ред. Закона №23-ЗРТ от 18 марта 2013 г «О внесении изменений в Закон Республики Татарстан "О государственных символах Республики Татарстан" в части утверждения текста Государственного гимна Республики Татарстан"». Вступил в силу со дня опубликования (28 августа 1999 г.). Опубликован: "Республика Татарстан", №174, 28 августа 1999 г. (Law #2284 of July 14, 1999 On the Symbols of State of the Republic of Tatarstan, as amended by the Law #23-ZRT of March 18, 2013 On Amending the Part of the Law of the Republic of Tatarstan "On the Symbols of State of the Republic of Tatarstan" Adopting the Text of the State Anthem of the Republic of Tatarstan. Effective as of the day of publication (August 28, 1999).).

- 6 ноября 1992 г. «Конституция Республики Татарстан», в ред. Закона №79-ЗРТ от 22 ноября 2010 г. «О внесении изменений в статьи 65 и 76 Конституции Республики Татарстан». Опубликован: "Ведомости Верховного Совета Татарстана", №9–10, ст. 166, 1992. (November 6, 1992 Constitution of the Republic of Tatarstan, as amended by the Law #79-ZRT of November 22, 2010 On Amending Articles 65 and 76 of the Constitution of the Republic of Tatarstan. ).

- Госкомстат РФ. Государственный комитет Республики Татарстан по статистике. "Административно-территориальное деление Республики Татарстан" (Administrative-Territorial Structure of the Republic of Tatarstan). Казань, 1997.

Further reading

- Ruslan Kurbanov. Tatarstan: Smooth Islamization Sprinkled with Blood OnIslam.net. Accessed: Feb. 26, 2013.

- Daniel Kalder. Lost Cosmonaut: Observations of an Anti-tourist.

- Ravil Bukharev. The Model of Tatarstan: Under President Mintimer Shaimiev.

- Azadeayse Rorlich. The Volga Tatars: A Profile in National Resilience.

- Roderick Heather. Russia From Red to Black

External links

![]()

![]()