Machine gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic mounted or portable firearm designed to fire rifle cartridges in rapid succession from an ammunition belt or magazine. Not all fully automatic firearms are machine guns. Submachine guns, rifles, assault rifles, battle rifles, shotguns, pistols or cannons may be capable of fully automatic fire, but are not designed for sustained fire. As a class of military rapid-fire guns, machine guns are fully automatic weapons designed to be used as support weapons and generally used when attached to a mount or fired from the ground on a bipod or tripod. Many machine guns also use belt feeding and open bolt operation, features not normally found on rifles.

Overview of modern machine guns

Unlike semi-automatic firearms, which require one trigger pull per round fired, a machine gun is designed to fire for as long as the trigger is held down. Nowadays the term is restricted to relatively heavy weapons, able to provide continuous or frequent bursts of automatic fire for as long as ammunition lasts. Machine guns are normally used against personnel, aircraft and light vehicles, or to provide suppressive fire, either directly or indirectly. They are commonly mounted on fast attack vehicles such as technicals to provide heavy mobile firepower, armored vehicles such as tanks for engaging targets too small to justify use of the primary weaponry or too fast to effectively engage with it, and on aircraft as defensive armament or for strafing ground targets, though on fighter aircraft true machine guns have mostly been supplanted by large-caliber rotary guns.

Some machine guns have in practice sustained fire almost continuously for hours; other automatic weapons overheat after less than a minute of use. Because they become very hot, the great majority of designs fire from an open bolt, to permit air cooling from the breech between bursts. They also usually have either a barrel cooling system, slow-heating heavyweight barrel, or removable barrels which allow a hot barrel to be replaced.

Although subdivided into "light", "medium", "heavy" or "general-purpose", even the lightest machine guns tend to be substantially larger and heavier than standard infantry arms. Medium and heavy machine guns are either mounted on a tripod or on a vehicle; when carried on foot, the machine gun and associated equipment (tripod, ammunition, spare barrels) require additional crew members.

Light machine guns are designed to provide mobile fire support to a squad and are typically air-cooled weapons fitted with a box magazine or drum and a bipod; they may use full-size rifle rounds, but modern examples often use intermediate rounds. Medium machine guns use full-sized rifle rounds and are designed to be used from fixed positions mounted on a tripod. Heavy machine gun is a term originating in World War I to describe heavyweight medium machine guns and persisted into World War II with Japanese Hotchkiss M1914 clones; today, however, it is used to refer to automatic weapons with a caliber of at least .50 in (12.7 mm)[1] but less than 20 mm. A general-purpose machine gun is usually a lightweight medium machine gun that can either be used with a bipod and drum in the light machine gun role or a tripod and belt feed in the medium machine gun role.

Machine guns usually have simple iron sights, though the use of optics is becoming more common. A common aiming system for direct fire is to alternate solid ("ball") rounds and tracer ammunition rounds (usually one tracer round for every four ball rounds), so shooters can see the trajectory and "walk" the fire into the target, and direct the fire of other soldiers.

Many heavy machine guns, such as the Browning M2 .50 caliber machine gun, are accurate enough to engage targets at great distances. During the Vietnam War, Carlos Hathcock set the record for a long-distance shot at 7,382 ft (2,250 m) with a .50 caliber heavy machine gun he had equipped with a telescopic sight.[2] This led to the introduction of .50 caliber anti-materiel sniper rifles, such as the Barrett M82.

Other automatic weapons are subdivided into several categories based on the size of the bullet used, whether the cartridge is fired from a closed bolt or an open bolt, and whether the action used is locked or is some form of blowback.

Fully automatic firearms using pistol-calibre ammunition are called machine pistols or submachine guns largely on the basis of size; those using shotgun cartridges are almost always referred to as automatic shotguns. The term personal defense weapon (PDW) is sometimes applied to weapons firing dedicated armor-piercing rounds which would otherwise be regarded as machine pistols or SMGs, but it is not particularly strongly defined and has historically been used to describe a range of weapons from ordinary SMGs to compact assault rifles. Selective fire rifles firing a full-power rifle cartridge from a closed bolt are called automatic rifles or battle rifles, while rifles that fire an intermediate cartridge are called assault rifles.

Assault rifles are a compromise between the size and weight of a pistol-calibre submachine gun and a full-size battle rifle, firing intermediate cartridges and allowing semi-automatic and burst or full-automatic fire options (selective fire), sometimes with both of the latter present.

Operation

Many machine guns are of the locked breech type, and follow this cycle:

- Pulling (manually or electrically) the bolt assembly/bolt carrier rearward by way of the cocking lever to the point bolt carrier engages a sear and stays at rear position until trigger is activated making bolt carrier move forward

- Loading fresh round into chamber and locking bolt

- Firing round by way of a firing pin or striker (except for aircraft medium calibre using electric ignition primers) hitting the primer that ignites the powder when bolt reaches locked position.

- Unlocking and removing the spent case from the chamber and ejecting it out of the weapon as bolt is moving rearward

- Loading the next round into the firing chamber. Usually, the recoil spring (also known as main spring) tension pushes bolt back into battery and a cam strips the new round from a feeding device, belt or box.

- Cycle is repeated as long as the trigger is activated by operator. Releasing the trigger resets the trigger mechanism by engaging a sear so the weapon stops firing with bolt carrier fully at the rear.

The operation is basically the same for all locked breech automatic firearms, regardless of the means of activating these mechanisms. There are also multi-chambered formats, such as revolver cannon, and some automatic weapons, including many submachine guns, the Schwarzlose machine gun etc., that do not lock at all but instead use simple blowback or some type of delayed blowback.

Design

Most modern machine guns are of the locking type, and of these, most utilize the principle of gas-operated reloading, which taps off some of the propellant gas from the fired cartridge, using its mechanical pressure to unlock the bolt and cycle the action. The Russian PK machine gun is an example. Another efficient and widely used format is the recoil actuated type, which uses the gun's recoil energy for the same purpose. Machine guns such as the M2 Browning and MG42, are of this second kind. A cam, lever or actuator absorbs part of the energy of the recoil to operate the gun mechanism.

An externally actuated weapon uses an external power source, such as an electric motor or hand crank, to move its mechanism through the firing sequence. Modern weapons of this type are often referred to as Gatling guns, after the original inventor (not only of the well-known hand-cranked 19th century proto-machine gun, but also of the first electrically-powered version). They have several barrels each with an associated chamber and action on a rotating carousel and a system of cams that load, cock, and fire each mechanism progressively as it rotates through the sequence; essentially each barrel is a separate bolt-action rifle using a common feed source. The continuous nature of the rotary action, and its relative immunity to overheating allow for an incredibly high cyclic rate of fire, often several thousand rounds per minute. Rotary guns are less prone to jamming than a gun operated by gas or recoil, as the external power source will eject misfired rounds with no further trouble, but this is not possible in the rare cases of self-powered rotary guns. Rotary designs are intrinsically comparatively bulky and expensive, and are therefore generally used with large rounds, 20 mm in diameter or more, often referred to as Rotary cannon – though the rifle-calibre Minigun is an exception to this. Whereas such weapons are highly reliable and formidably effective, one drawback is that the weight and size of the power source and driving mechanism makes them usually impractical for use outside of a vehicle or aircraft mount.

Revolver cannons, such as the Mauser MK 213, were developed in World War II by the Germans to provide high-caliber cannons with a reasonable rate of fire and reliability. In contrast to the rotary format, such weapons have a single barrel, and a recoil-operated carriage holding a revolving chamber with typically five chambers. As each round is fired, electrically, the carriage moves back rotating the chamber which also ejects the spent case, indexes the next live round to be fired with the barrel and loads the next round into the chamber. The action is very similar to that of the revolver pistols common in the 19th and 20th centuries, giving this type of weapon its name. A Chain gun is a specific, patented type of Revolver cannon, the name in this case deriving from its driving mechanism.

Firing a machine gun for prolonged periods produces large amounts of heat. In a worst-case scenario this may cause a cartridge to overheat and detonate even when the trigger is not pulled, potentially leading to damage or causing the gun to cycle its action and keep firing until it has exhausted its ammunition supply or jammed (this is known as cooking off, distinct from runaway fire where the sear fails to re-engage when the trigger is released). To prevent this, some kind of cooling system is required. Early machine guns were often water-cooled; while this technology was very effective, (and was indeed one of the sources of the notorious efficiency of machine guns during the First World War ), the water jackets also added considerable weight to an already bulky design; they were also vulnerable to bullets themselves. Armour could of course be provided, and in WW I the Germans in particular often did this; but this added yet more weight to the guns. Air-cooled machine guns often feature quick-change barrels (often carried by a crew member), passive cooling fins, or in some designs forced-air cooling, such as that employed by the Lewis Gun. Advances in metallurgy and use of special composites in barrel liners allow for greater heat absorption and dissipation during firing. The higher the rate of fire, the more often barrels must be changed and allowed to cool. To minimize this, most air-cooled guns are fired only in short bursts or at a reduced rate of fire. Some designs – such as the many variants of the MG42 – are capable of rates of fire in excess of 1,200 rounds per minute. Gatling guns are capable of the fastest firing rates of all, partly because this format involves extra energy being injected into the system from outside, instead of depending on energy derived from the propellant contained within the cartridges, and partly because this design deals with the unwanted heat most efficiently – effectively quick-changing the barrel and chamber after every shot. The multiple guns that comprise a Gatling being a much larger bulk of metal than other, single-barreled guns, they are thus much slower to rise in temperature for a given amount of heat. Simultaneously they are much better at shedding the excess, as the extra barrels not only provide a larger surface area from which to dissipate it, but in the nature of the design are spun at very high speed, which has the benefit of producing enhanced air-cooling as a side-effect.

In weapons where the round seats and fires at the same time, mechanical timing is essential for operator safety, to prevent the round from firing before it is seated properly. Machine guns are controlled by one or more mechanical sears. When a sear is in place, it effectively stops the bolt at some point in its range of motion. Some sears stop the bolt when it is locked to the rear. Other sears stop the firing pin from going forward after the round is locked into the chamber. Almost all machine guns have a "safety" sear, which simply keeps the trigger from engaging.

History

_-_mitraljezi.jpg)

The first successful machine-gun designs were developed in the mid-19th century. The key characteristic of modern machine guns, their relatively high rate of fire and more importantly mechanical loading,[3] first appeared in the Model 1862 Gatling gun, which was adopted by the United States Navy. These weapons were still powered by hand; however, this changed with Hiram Maxim's idea of harnessing recoil energy to power reloading in his Maxim machine gun. Dr. Gatling also experimented with electric-motor-powered models; as discussed above, this externally powered machine reloading has seen use in modern weapons as well.

While technical use of the term "machine gun" has varied, the modern definition used by the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers' Institute of America is "a fully automatic firearm that loads, fires and ejects continuously when the trigger is held to the rear until the ammunition is exhausted or pressure on the trigger is released."[3] This definition excludes most early manually operated repeating arms such as volley guns and the Gatling gun.

Early rapid-firing weapons

The first known ancestors of multi-shot weapons were medieval organ guns, while the first to have the ability to fire multiple shots from a single barrel without a full manual reload were revolvers made in Europe in the late 1500s. One is a shoulder-gun-length weapon made in Nuremberg, Germany, circa 1580. Another is a revolving arquebus, produced by Hans Stopler of Nuremberg in 1597.[4]

True repeating long arms were difficult to manufacture prior to the development of the unitary firearm cartridge; nevertheless, lever-action repeating rifles such as the Kalthoff repeater and Cookson repeater were made in small quantities in the 17th century.

Perhaps the earliest examples of predecessors to the modern machine gun are to be found in East Asia. According to the Wu-Pei-Chih, a booklet examining Chinese military equipment produced during the first quarter of the 17th century, the Chinese army had in its arsenal the 'Po-Tzu Lien-Chu-P'ao' or 'string-of-100-bullets cannon'. This was a repeating cannon fed by a hopper which fired its charges sequentially.[5] Another repeating gun was produced by a Chinese commoner in the late 17th century. This weapon was also hopper-fed and never went into mass production.[6]

In 1663 the first mention of the automatic principle of machine guns was in a paper presented to the Royal Society of England by an Englishman by the name of Palmer who described a volley gun capable of being operated by either recoil or gas.[7]

Another early revolving gun was created by James Puckle, a London lawyer, who patented what he called "The Puckle Gun" on May 15, 1718. It was a design for a manually operated 1.25 in. (32 mm) caliber, flintlock cannon with a revolver cylinder able to fire 6–11 rounds before reloading by swapping out the cylinder, intended for use on ships. It was one of the earliest weapons to be referred to as a machine gun, being called such in 1722,[9] though its operation does not match the modern usage of the term. According to Puckle, it was able to fire round bullets at Christians and square bullets at Turks.[8] However, it was a commercial failure and was not adopted or produced in any meaningful quantity.

In 1777, Philadelphia gunsmith Joseph Belton offered the Continental Congress a "new improved gun", which was capable of firing up to twenty shots in five seconds; unlike older repeaters using complex lever-action mechanisms, it used a simpler system of superposed loads, and was loaded with a single large paper cartridge. Congress requested that Belton modify 100 flintlock muskets to fire eight shots in this manner, but rescinded the order when Belton's price proved too high.[10][11]

In the early and mid-19th century, a number of rapid-firing weapons appeared which offered multi-shot fire, mostly volley guns. Volley guns (such as the Mitrailleuse) and double-barreled pistols relied on duplicating all parts of the gun, though the Nock gun used the otherwise-undesirable "chain fire" phenomenon (where multiple chambers are ignited at once) to propagate a spark from a single flintlock mechanism to multiple barrels. Pepperbox pistols also did away with needing multiple hammers but used multiple manually operated barrels. Revolvers further reduced this to only needing a pre-prepared cylinder and linked advancing the cylinder to cocking the hammer. However, these were still manually operated.

In the 1830s a machine gun was designed by a Swiss man called Jacob Steuble, who tried to sell it to the Russian, English and French governments. The English and Russian governments showed interest but the former refused to pay Steuble, who later sued them for this transgression, and the latter tried to imprison him. The French government showed interest at first and while they noted that mechanically there was nothing wrong with Steuble's invention they turned him down, stating that the machine both lacked novelty and could not be usefully employed by the army.[12][13][14]

In 1847 a short description of a prototype electrically-ignited mechanical machine gun was published in Scientific American by a J.R. Nichols. The model described is small in scale and works by rotating a series of barrels vertically so that it is feeding at the top from a 'tube' or hopper and could be discharged immediately at any elevation after having received a charge, according to the author.[15]

In 1848 an Italian by the name of Cesar Rosaglio announced his invention of a machine gun capable of being operated by a single man and firing 300 shots a minute or 12,000 in an hour after taking into account the time needed to reload the 'tanks' of ammunition.[16]

In June 1851 a model of a 'war engine' allegedly capable of firing 10,000 ball cartridges in 10 minutes was demonstrated by a British inventor called Francis McGetrick.[17]

In 1852 a rotary cannon using a unique form of wheellock ignition was designed by an Irish immigrant to America by the name of Delany.[18]

In 1854 a British patent for a mechanically operated machine gun was filed by Henry Clarke. This weapon used multiple barrels arranged side by side, fed by a revolving cylinder that was in turn fed by hoppers, similar to the system used by Nichols. The gun could be fired by percussion or electricity, according to the author. Unlike other mechanically operated machine guns of the era, this weapon didn't use any form of self-contained cartridge, with firing being carried out by separate percussion caps.[19] In the same year, water cooling was proposed for machine guns by Henry Bessemer, along with a water cleaning system, though he later abandoned this design. In his patent, Bessemer describes a hydropneumatic blowback-operated, fully automatic cannon. Part of the patent also refers to a steam-operated piston to be used with firearms but the bulk of the patent is spent detailing the former system.[20]

In America, a patent for a machine gun type weapon was filed by John Andrus Reynolds in 1855.[21] Another early American patent for a manually operated machine gun was filed by C. E. Barnes in 1856.[22]

In France and Britain, a mechanically operated machine gun was patented in 1856 by the Frenchman Francois Julien. This weapon was a cannon that fed from a type of open-ended tubular magazine, only using rollers and an endless chain in place of springs.[23]

The Agar Gun, otherwise known as a "coffee-mill gun" because of its resemblance to a coffee mill, was invented by Wilson Agar at the beginning of the US Civil War. The weapon featured mechanized loading using a hand crank linked to a hopper above the weapon. The weapon featured a single barrel and fired through the turning of the same crank; it operated using paper cartridges fitted with percussion caps and inserted into metal tubes which acted as chambers; it was therefore functionally similar to a revolver. The weapon was demonstrated to President Lincoln in 1861. He was so impressed with the weapon that he purchased 10 on the spot for $1,500 apiece. The Union Army eventually purchased a total of 54 of the weapons. However, due to antiquated views of the Ordnance Department the weapons, like its more famous counterpart the Gatling Gun, saw only limited use.

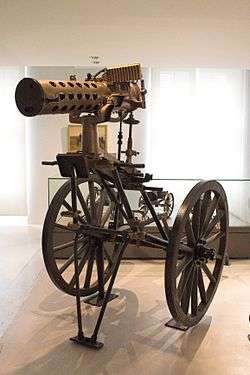

The Gatling gun, patented in 1861 by Richard Jordan Gatling, was the first to offer controlled, sequential fire with mechanical loading. The design's key features were machine loading of prepared cartridges and a hand-operated crank for sequential high-speed firing. It first saw very limited action in the American Civil War; it was subsequently improved and used in the Franco-Prussian war and North-West Rebellion. Many were sold to other armies in the late 19th century and continued to be used into the early 20th century, until they were gradually supplanted by Maxim guns. Early multi-barrel guns were approximately the size and weight of contemporary artillery pieces, and were often perceived as a replacement for cannon firing grapeshot or canister shot.[24] The large wheels required to move these guns around required a high firing position, which increased the vulnerability of their crews.[24] Sustained firing of gunpowder cartridges generated a cloud of smoke, making concealment impossible until smokeless powder became available in the late 19th century.[25] Gatling guns were targeted by artillery they could not reach, and their crews were targeted by snipers they could not see.[24] The Gatling gun was used most successfully to expand European colonial empires, since against poorly equipped indigenous armies it did not face such threats.[24]

In 1870 a Lt. D. H. Friberg of the Swedish army patented a fully automatic recoil-operated firearm action and may have produced firing prototypes of a derived design around 1882: this was the forerunner to the 1907 Kjellman machine gun, though, due to rapid residue buildup from the use of black powder, Friberg's design was not a practical weapon.[26]

Also in 1870, the Bavarian regiment of the Prussian army used a unique mitrailleuse style weapon in the Franco-Prussian war. The weapon was made up of four barrels placed side by side that replaced the manual loading of the French mitrailleuse with a mechanical loading system featuring a hopper containing 41 cartridges at the breech of each barrel. Although it was used effectively at times, mechanical difficulties hindered its operation and it was ultimately abandoned shortly after the war ended (de).[27]

Maxim and World War I

The first practical self-powered machine gun was invented in 1884 by Sir Hiram Maxim. The Maxim machine gun used the recoil power of the previously fired bullet to reload rather than being hand-powered, enabling a much higher rate of fire than was possible using earlier designs such as the Nordenfelt and Gatling weapons. Maxim also introduced the use of water cooling, via a water jacket around the barrel, to reduce overheating. Maxim's gun was widely adopted, and derivative designs were used on all sides during the First World War. The design required fewer crew and was lighter and more usable than the Nordenfelt and Gatling guns. First World War combat experience demonstrated the military importance of the machine gun. The United States Army issued four machine guns per regiment in 1912, but that allowance increased to 336 machine guns per regiment by 1919.[28]

Heavy guns based on the Maxim such as the Vickers machine gun were joined by many other machine weapons, which mostly had their start in the early 20th century such as the Hotchkiss machine gun. Submachine guns (e.g., the German MP 18) as well as lighter machine guns (the first light machine gun deployed in any significant number being the Madsen machine gun, with the Chauchat and Lewis gun soon following) saw their first major use in World War I, along with heavy use of large-caliber machine guns. The biggest single cause of casualties in World War I was actually artillery, but combined with wire entanglements, machine guns earned a fearsome reputation.

Another fundamental development occurring before and during the war was the incorporation by gun designers of machine gun auto-loading mechanisms into handguns, giving rise to semi-automatic pistols such as the Borchardt (1890s), automatic machine pistols and later submachine guns (such as the Beretta 1918).

Machine guns were mounted in aircraft for the first time in World War I. Immediately this raised a problem. The most effective position for guns in a single-seater fighter was clearly, for the purpose of aiming, directly in front of the pilot; but this placement would obviously result in bullets striking the moving propeller. Early solutions, aside from simply hoping that luck was on the pilot's side with an unsynchronized forward-firing gun, involved either aircraft with pusher props like the Vickers F.B.5, Royal Aircraft Factory F.E.2 and Airco DH.2, wing mounts like that of the Nieuport 10 and Nieuport 11 which avoided the propeller entirely, or armored propeller blades such as those mounted on the Morane-Saulnier L which would allow the propeller to deflect unsynchronized gunfire. By mid 1915, the introduction of a reliable gun synchronizer by the Imperial German Flying Corps made it possible to fire a closed-bolt machine gun forward through a spinning propeller by timing the firing of the gun to miss the blades. The Allies had no equivalent system until 1916 and their aircraft suffered badly as a result, a period known as the Fokker Scourge, after the Fokker Eindecker, the first German plane to incorporate the new technology.

Interwar era and World War II

As better materials became available following the First World War, light machine guns became more readily portable; designs such as the Bren light machine gun replaced bulky predecessors like the Lewis gun in the squad support weapon role, while the modern division between medium machine guns like the M1919 Browning machine gun and heavy machine guns like the Browning M2 became clearer. New designs largely abandoned water jacket cooling systems as both undesirable, due to a greater emphasis on mobile tactics and unnecessary, thanks to the alternative and superior technique of preventing overheating by swapping barrels.

The interwar years also produced the first widely used and successful general-purpose machine gun, the German MG 34. While this machine gun was equally able in the light and medium roles, it proved difficult to manufacture in quantity, and experts on industrial metalworking were called in to redesign the weapon for modern tooling, creating the MG 42. This weapon was simpler, cheaper to produce, fired faster, and replaced the MG 34 in every application except vehicle mounts, since the MG 42's barrel changing system could not be operated when it was mounted.

Cold War

Experience with the MG42 led to the US issuing a requirement to replace the aging Browning Automatic Rifle with a similar weapon, which would also replace the M1919; simply using the MG42 itself was not possible, as the design brief required a weapon which could be fired from the hip or shoulder like the BAR. The resulting design, the M60 machine gun, was issued to troops during the Vietnam War.

As it became clear that a high-volume-of-fire weapon would be needed for fast-moving jet aircraft to reliably hit their opponents, Gatling's work with electrically powered weapons was recalled and the 20 mm M61 Vulcan designed; a miniaturized 7.62 mm version initially known as the "mini-Vulcan" and quickly shortened to "minigun" was soon in production for use on helicopters, where the volume of fire could compensate for the instability of the helicopter as a firing platform.

Human interface

The most common interface on machine guns is a pistol grip and trigger. On earlier manual machine guns, the most common type was a hand crank. On externally powered machine guns, such as miniguns, an electronic button or trigger on a joystick is commonly used. Light machine guns often have a butt stock attached, while vehicle and tripod mounted machine guns usually have spade grips. In the late 20th century, scopes and other complex optics became more common as opposed to the more basic iron sights.

Loading systems in early manual machine guns were often from a hopper of loose (un-linked) cartridges. Manual-operated volley guns usually had to be reloaded manually all at once (each barrel reloaded by hand, or with a set of cartridges affixed to a plate that was inserted into the weapon). With hoppers, the rounds could often be added while the weapon was firing. This gradually changed to belt-fed types. Belts were either held in the open by the person, or in a bag or box. Some modern vehicle machine guns used linkless feed systems however.

Modern machine guns are commonly mounted in one of four ways. The first is a bipod – often these are integrated with the weapon. This is common on light machine guns and some medium machine guns. Another is a tripod, where the person holding it does not form a "leg" of support. Medium and heavy machine guns usually use tripods. On ships, vehicles and aircraft machine guns are usually mounted on a pintle mount – basically a steel post that is connected to the frame or body. Tripod and pintle mounts are usually used with spade grips. The last major mounting type is one that is disconnected from humans, as part of an armament system, such as a tank coaxial or part of an aircraft's armament. These are usually electrically fired and have complex sighting systems, for example, the US Helicopter Armament Subsystems.

See also

- Assault rifle

- Autocannon

- Breda (machine gun)

- Chain gun

- Firearm action

- Gatling gun

- General-purpose machine gun

- Heavy machine gun

- Light machine gun

- List of firearms

- List of machine guns

- List of multiple barrel machine guns

- Medium machine gun

- Minigun

- Mitrailleuse

- Personal defense weapon

- Revolver cannon

- Squad automatic weapon

- Submachine gun

References

- "Machine Guns and Machine Gun Gunnery" (PDF). US Marine Corps. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 February 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- Henderson, Charles (2005). Marine Sniper. Berkley Caliber. ISBN 0-425-10355-2.

- "SAAMI.org terminology glossary". Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers' Institute. Archived from the original on 2003-08-24. Retrieved 2015-08-23.

- Roger Pauly (2004). Firearms: The Life Story of a Technology. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32796-4.

- Song, Yingxing; Sun, E-tu Zen; Sun, Shiou-Chuan (1997). Chinese Technology in the Seventeenth Century. Courier Corporation. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-486-29593-0.

- Needham, Joseph (1987). Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7, Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge University Press. p. 408. ISBN 978-0-521-30358-3.

- Willbanks, James H. (April 10, 2004). "Machine Guns: An Illustrated History of Their Impact". ABC-CLIO – via Google Books.

- "The Armoury of His Grace the Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry" (PDF). University of Huddersfield. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-08-23.

- Harold L. Peterson (2000). Arms and Armor in Colonial America, 1526–1783. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 217–18. ISBN 978-0-486-41244-3.

- United States Continental Congress (1907). Journals of the Continental Congress. USGPO. pp. 324, 361.

- Lenotre, G (2014). Vieilles Maisons, Vieux Papiers. Tallandier. p. 81. ISBN 979-1-02-100758-1.

- "Infernal Machine". John Bull "For God, the King, and the People!". XVI (807). Retrieved 2019-08-26 – via LastChanceToRead.com.

- "La Presse". Gallica (in French). 1838-05-22. Retrieved 2019-08-26.

- Scientific American. Munn & Company. 1847. p. 172.

- AC09990011, Anonymus (April 10, 1848). "Foglio ufficiale. L'Indipendente dell' alto Po". Feraboli – via Google Books.

- Ellis (F.L.S.), Robert (April 10, 1851). "Index and introductory. Raw materials. Machinery.-v.2. Manufactures. Fine arts. Colonies.-v.3 Foreign states". Spicer brothers – via Google Books.

- Tompkins, William Ward (April 10, 1851). "United Service Journal: Devoted to the Army, Navy and Militia of the United States". W.W. Tompkins – via Google Books.

- office, Great Britain Patent; Woodcroft, Bennet (23 December 2017). "Abridgments of the Specifications Relating to Fire-arms and Other Weapons, Ammunition, and Accoutrements: A.D. 1588–1858]-Pt. II. A.D. 1858–1866". Printed by George E. Eyre and William Spottiswoode, pub. at the Great seal patent office. p. 163.

- "Provisional Specifications Not Proceeded with". Mechanic's Magazine. R. A. Brooman. 1855. p. 259.

- "Improvement in fire-arms". Google Patents. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- "HyperWar: The Machine Gun (Vol. /Part )". Ibiblio.org. Archived from the original on 25 December 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- Office, Patent (1859). Patents for inventions. Abridgments of specifications. p. 265.

- Emmott, N.W. "The Devil's Watering Pot" United States Naval Institute Proceedings September 1972 p. 70

- Emmott, N.W. "The Devil's Watering Pot" United States Naval Institute Proceedings September 1972 p. 72

- "HyperWar: The Machine Gun (Vol. I/Part III)". Ibiblio.org. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2017.

- Smithurst, Peter (2015). The Gatling Gun. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-4728-0598-0.

- Ayres, Leonard P. (1919). The War with Germany (Second ed.). Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. p. 65.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Machine guns. |

- Discover Military Machine Guns

- "From Gatling to Browning"—September 1945 article in Popular Science

- "How Machine Guns Work" – HowStuffWorks article on the operation of Machine Guns, animated diagrams are included

- The REME Museum of Technology – machine guns

- U.S. Patent 15,315 – A patent for an early automatic cannon

- Vickers machine gun site