International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919)

This article covers worldwide diplomacy and, more generally, the international relations of the great powers from 1814 to 1919. The international relations of minor countries are covered in their own history articles. This era covers the period from the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the Congress of Vienna (1814–15), to the end of the First World War and the Paris Peace Conference. For the previous era see International relations, 1648–1814. For the 1920s and 1930s see International relations (1919–1939).

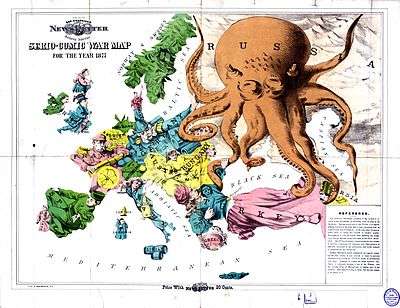

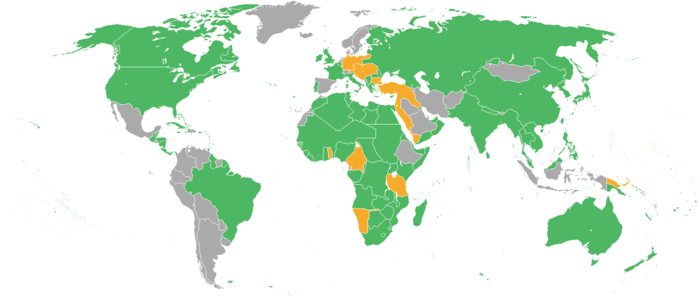

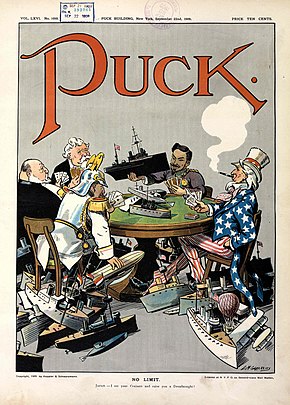

Important themes include the rapid industrialization and growing power of Britain, France and Prussia/Germany, and, later in the period, the United States, Italy and Japan. This led to imperialist and colonialist competitions for influence and power throughout the world, most famously the Scramble for Africa in the 1880s and 1890s. The reverberations are still widespread and consequential in the 21st century. Britain established an informal economic network that, combined with its colonies and its Royal Navy, made it the hegemonic nation until its power was challenged by the united Germany. It was a largely peaceful century, with no wars between the great powers, apart from the 1854–1871 interval, and some small wars between Russia and the Ottoman Empire. After 1900 there were a series of wars in the Balkan region, which exploded out of control into World War I (1914–1918)—a massively devastating event that was unexpected in its timing, duration, casualties, and long-term impact.

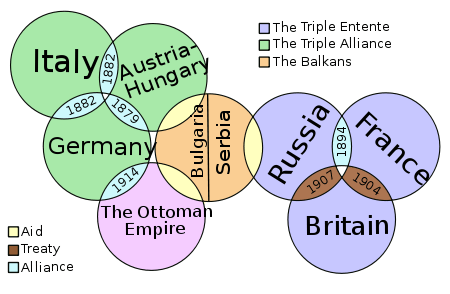

In 1814 diplomats recognised five Great Powers: France, Britain, Russia, Austria (in 1867–1918, Austria–Hungary) and Prussia (in 1871 the German Empire). Italy was added to this group after the Risorgimento and on the eve of the First World War there were two major blocs in Europe: the Triple Entente formed by France, Britain and Russia and the Triple Alliance formed by Germany, Italy and Austria-Hungary. The Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Greece, Portugal, Spain, and Switzerland were smaller powers. Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro, and Albania initially operated as autonomous vassals for they were legally still part of the declining Ottoman Empire, which may also be included among the major powers, before gaining their independence.[1] By 1905 two rapidly growing non-European states, Japan and the United States, had joined the Great Powers. The Great War unexpectedly tested their military, diplomatic, social and economic capabilities to the limit.[2] Germany, Austria–Hungary and the Ottoman Empire were defeated; Germany lost its great power status, and the others were broken up into collections of states. The winners Britain, France, Italy and Japan gained permanent seats at the governing council of the new League of Nations. The United States, meant to be the fifth permanent member, decided to operate independently and never joined the League. For the following periods see Diplomatic history of World War I and International relations (1919–1939).

1814–1830: Restoration and reaction

As the four major European powers (Britain, Prussia, Russia and Austria) opposing the French Empire in the Napoleonic Wars saw Napoleon's power collapsing in 1814, they started planning for the postwar world. The Treaty of Chaumont of March 1814 reaffirmed decisions that had been made already and which would be ratified by the more important Congress of Vienna of 1814–15. They included the establishment of a confederated Germany including both Austria and Prussia (plus the Czech lands), the division of French protectorates and annexations into independent states, the restoration of the Bourbon kings of Spain, the enlargement of the Netherlands to include what in 1830 became modern Belgium, and the continuation of British subsidies to its allies. The Treaty of Chaumont united the powers to defeat Napoleon and became the cornerstone of the Concert of Europe, which formed the balance of power for the next two decades.[3][4]

One goal of diplomacy throughout the period was to achieve a "balance of power", so that no one or two powers would be dominant.[5] If one power gained an advantage—for example by winning a war and acquiring new territory—its rivals might seek "compensation"—that is, territorial or other gains, even though they were not part of the war in the first place. The bystander might be angry if the winner of the war did not provide enough compensation. For example, in 1866, Prussia and supporting north German States defeated Austria and its southern German allies, but France was angry that it did not get any compensation to balance off the Prussian gains.[6]

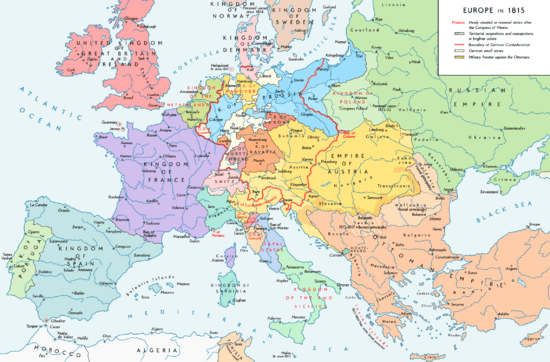

Congress of Vienna: 1814–1815

The Congress of Vienna (1814–1815) dissolved the Napoleonic Wars and attempted to restore the monarchies Napoleon had overthrown, ushering in an era of reaction.[7] Under the leadership of Metternich, the prime minister of Austria (1809–1848), and Lord Castlereagh, the foreign minister of Great Britain (1812–1822), the Congress set up a system to preserve the peace. Under the Concert of Europe (or "Congress system"), the major European powers—Britain, Russia, Prussia, Austria, and (after 1818) France—pledged to meet regularly to resolve differences. This plan was the first of its kind in European history and seemed to promise a way to collectively manage European affairs and promote peace. It was the forerunner of the League of Nations and the United Nations but it collapsed by 1823.[8][9]

The Congress resolved the Polish–Saxon crisis at Vienna and the question of Greek independence at Laibach (Ljubljana). Three major European congresses took place. The Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle (1818) ended the military occupation of France and adjusted downward the 700 million francs the French were obligated to pay as reparations. The Russian tsar proposed the formation of an entirely new alliance, to include all of the signatories from the Vienna treaties, to guarantee the sovereignty, territorial integrity, and preservation of the ruling governments of all members of this new coalition. The tsar further proposed an international army, with the Russian army as its nucleus, to provide the wherewithal to intervene in any country that needed it. Lord Castlereagh saw this as a highly undesirable commitment to reactionary policies. He recoiled at the idea of Russian armies marching across Europe to put down popular uprisings. Furthermore, to admit all the smaller countries would create intrigue and confusion. Britain refused to participate, so the idea was abandoned.[10]

The other meetings proved meaningless as each nation realized the Congresses were not to their advantage, where disputes were resolved with a diminishing degree of effectiveness.[11][12][13][14]

To achieve lasting peace, the Concert of Europe tried to maintain the balance of power. Until the 1860s the territorial boundaries laid down at the Congress of Vienna were maintained, and even more importantly, there was an acceptance of the theme of balance with no major aggression.[15] Otherwise, the Congress system had "failed" by 1823.[12][16] In 1818 the British decided not to become involved in continental issues that did not directly affect them. They rejected the plan of Tsar Alexander I to suppress future revolutions. The Concert system fell apart as the common goals of the Great Powers were replaced by growing political and economic rivalries.[11] Artz says the Congress of Verona in 1822 "marked the end".[17] There was no Congress called to restore the old system during the great revolutionary upheavals of 1848 with their demands for revision of the Congress of Vienna's frontiers along national lines.[18][19]

British policies

British foreign policy was set by George Canning (1822–1827), who avoided close cooperation with other powers. Britain, with its unchallenged Royal Navy and increasing financial wealth and industrial strength, built its foreign policy on the principle that no state should be allowed to dominate the Continent. It wanted to support the Ottoman Empire as a bulwark against Russian expansionism. It opposed interventions designed to suppress democracy, and was especially worried that France and Spain planned to suppress the independence movement underway in Latin America. Canning cooperated with the United States to promulgate the Monroe Doctrine to preserve newly independent Latin American states. His goal was to prevent French dominance and allow British merchants access to the opening markets.[20]

Slave trade

An important liberal advance was the abolition of the international slave trade. It began with legislation in Britain and the United States in 1807, which was increasingly enforced over subsequent decades by the British Royal Navy under treaties Britain negotiated, or coerced, other nations into agreeing.[21] The result was a reduction of over 95% in the volume of the slave trade from Africa to the New World. About 1000 slaves a year were illegally brought into the United States, as well as some to Cuba and Brazil.[22] Slavery was abolished in the British Empire in 1833, the French Republic in 1848, the United States in 1865, and Brazil in 1888.[23]

Spain loses its colonies

Spain was at war with Britain from 1798 to 1808, and the British Royal Navy cut off its contacts with its colonies. Trade was handled by neutral American and Dutch traders. The colonies set up temporary governments or juntas which were effectively independent from Spain. The division exploded between Spaniards who were born in Spain (called peninsulares) versus those of Spanish descent born in New Spain (called criollos in Spanish or "creoles" in English). The two groups wrestled for power, with the criollos leading the call for independence and eventually winning that independence. Spain lost all of its American colonies, except Cuba and Puerto Rico, in a complex series of revolts from 1808 to 1826.[24][25]

Multiple revolutions in Latin America allowed the region to break free of the mother country. Repeated attempts to regain control failed, as Spain had no help from European powers. Indeed, Britain and the United States worked against Spain, enforcing the Monroe Doctrine. British merchants and bankers took a dominant role in Latin America. In 1824, the armies of generals José de San Martín of Argentina and Simón Bolívar of Venezuela defeated the last Spanish forces; the final defeat came at the Battle of Ayacucho in southern Peru. After the loss of its colonies, Spain played a minor role in international affairs. Spain kept Cuba, which repeatedly revolted in three wars of independence, culminating in the Cuban War of Independence. The United States demanded reforms from Spain, which Spain refused. The U.S. intervened by war in 1898. Winning easily, the U.S. took Cuba and gave it independence. The U.S. also took the Spanish colonies of the Philippines and Guam.[26] Though it still had small colonial holdings in North Africa and Equatorial Guinea, Spain's role in international affairs was essentially over.

Greek independence: 1821–1833

The Greek War of Independence was the major military conflict in the 1820s. The Great Powers supported the Greeks, but did not want the Ottoman Empire destroyed. Greece was initially to be an autonomous state under Ottoman suzerainty, but by 1832, in the Treaty of Constantinople, it was recognized as a fully independent kingdom.[27]

After some initial success the Greek rebels were beset by internal disputes. The Ottomans, with major aid from Egypt, cruelly crushed the rebellion and harshly punished the Greeks. Humanitarian concerns in Europe were outraged, as typified by English poet Lord Byron. The context of the three Great Powers' intervention was Russia's long-running expansion at the expense of the decaying Ottoman Empire. However Russia's ambitions in the region were seen as a major geostrategic threat by the other European powers. Austria feared the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire would destabilize its southern borders. Russia gave strong emotional support for the fellow Orthodox Christian Greeks. The British were motivated by strong public support for the Greeks. Fearing unilateral Russian action in support of the Greeks, Britain and France bound Russia by treaty to a joint intervention which aimed to secure Greek autonomy whilst preserving Ottoman territorial integrity as a check on Russia.[28][29]

The Powers agreed, by the Treaty of London (1827), to force the Ottoman government to grant the Greeks autonomy within the empire and despatched naval squadrons to Greece to enforce their policy.[30] The decisive Allied naval victory at the Battle of Navarino broke the military power of the Ottomans and their Egyptian allies. Victory saved the fledgling Greek Republic from collapse. But it required two more military interventions, by Russia in the form of the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–29 and by a French expeditionary force to the Peloponnese to force the withdrawal of Ottoman forces from central and southern Greece and to finally secure Greek independence.[31]

Travel, trade and communications

The world became much smaller as long-distance travel and communications improved dramatically. Every decade there were more ships, more scheduled destinations, faster trips, and lower fares for passengers and cheaper rates for merchandise. This facilitated international trade and international organization.[32]

Travel

Underwater telegraph cables linked the world's major trading nations by the 1860s.[33]

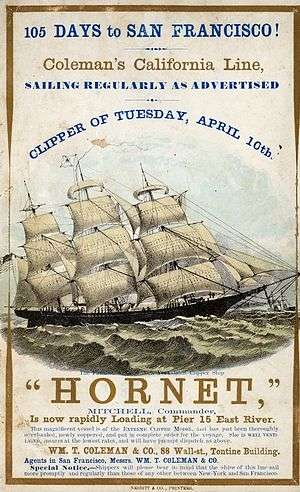

Cargo sailing ships were slow; historians estimate that the average speed of all long-distance Mediterranean voyages to Palestine was only 2.8 knots.[34] Passenger ships achieved greater speed by sacrificing cargo space. The sailing ship records were held by the clipper, a very fast sailing ship of the 1843–1869 era. Clippers were narrow for their length, could carry limited bulk freight, small by later 19th-century standards, and had a large total sail area. Their average speed was six knots and they carried passengers across the globe, primarily on the trade routes between Britain and its colonies in the east, in trans-Atlantic trade, and the New York-to-San Francisco route round Cape Horn during the California Gold Rush.[35] The much faster steam-powered, iron-hulled ocean liner became the dominant mode of passenger transportation from the 1850s to the 1950s. It used coal—and needed many coaling stations. After 1900 oil became the favoured fuel and did not require frequent refueling.

Transportation

Freight rates on ocean traffic held steady in the 18th century down to about 1840, and then began a rapid downward plunge. The British dominated world exports, and rates for British freight fell 70% from 1840 to 1910.[36] The Suez Canal cut the shipping time from London to India by a third when it opened in 1869. The same ship could make more voyages in a year, so it could charge less and carry more goods every year.[37][38]

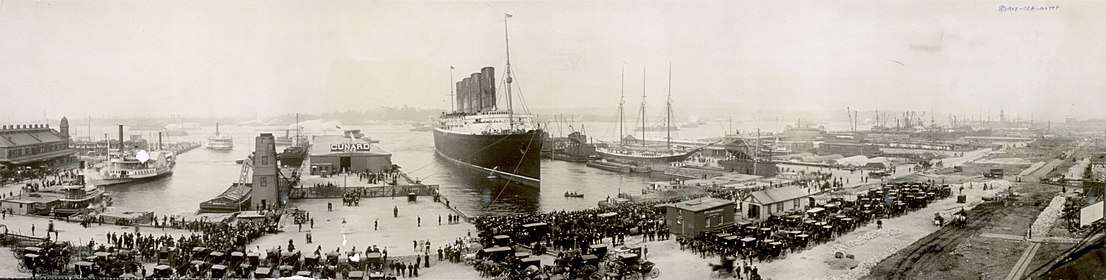

Technological innovation was steady. Iron hulls replaced wood by mid-century; after 1870, steel replaced iron. It took much longer for steam engines to replace sails.[39] Note the sailing ship across from the Lusitania in the photograph above. Wind was free, and could move the ship at 2–3 knots, unless it was becalmed. Coal was expensive and required coaling stations along the route. A common solution was for a merchant ship to rely mostly on its sails, and only use the steam engine as a backup.[40] The first steam engines were very inefficient, using a great deal of coal. For an ocean voyage in the 1860s, half of the cargo space was given over to coal. The problem was especially acute for warships, because their combat range using coal was strictly limited. Only the British Empire had a network of coaling stations that permitted a global scope for the Royal Navy.[41] Steady improvement gave high-powered compound engines which were much more efficient. The boilers and pistons were built of steel, which could handle much higher pressures than iron. They were first used for high-priority cargo, such as mail and passengers.[42] The arrival of the steam turbine engine around 1907 dramatically improved efficiency, and the increasing use of oil after 1910 meant far less cargo space had to be devoted to the fuel supply.[43]

Communications

By the 1850s, railways and telegraph lines connected all the major cities inside Western Europe, as well as those inside the United States. Instead of greatly reducing the need for travel, the telegraph made travel easier to plan and replaced the slow long-distance mail service.[44] Submarine cables were laid to link the continents by telegraph, which was a reality by the 1860s.[45][46][47]

1830–1850s

Britain continued as the most important power, followed by Russia, France, Prussia and Austria. The United States was growing rapidly in size, population and economic strength, especially after its defeat of Mexico in 1848. Otherwise it avoided international entanglements as the slavery issue became more and more divisive.

The Crimean War (1853–1856) was the most important war, especially because it disrupted the stability of the system. Britain strengthened its colonial system, especially in India, while France rebuilt its empire in Asia and North Africa. Russia continued its expansion south (toward Persia) and east (into Siberia). The Ottoman Empire steadily weakened, losing control in parts of the Balkans to the new states of Greece and Serbia.[48][49]

In the Treaty of London, signed in 1839, the Great Powers guaranteed the neutrality of Belgium. Germany called it a "scrap of paper" and violated it in 1914 by invasion, whereupon Britain declared war on Germany.[50]

British policies

The repeal in 1846 of the tariff on food imports, called the Corn Laws, marked a major turning point that made free trade the national policy of Great Britain into the 20th century. Repeal demonstrated the power of "Manchester-school" industrial interests over protectionist agricultural interests.[51]

From 1830 to 1865, with a few interruptions, Lord Palmerston set British foreign policy. He had six main goals that he pursued: first he defended British interests whenever they seemed threatened, and upheld Britain's prestige abroad. Second he was a master at using the media to win public support from all ranks of society. Third he promoted the spread of constitutional Liberal governments like in Britain, along the model of the 1832 Reform Act. He therefore welcomed liberal revolutions as in France (1830), and Greece (1843). Fourth he promoted British nationalism, looking for advantages for his nation as an the Belgian revolt of 1830 and the Italian unification of 1859. He avoided wars, and operated with only a very small British Army. He felt the best way to promote peace was to maintain a balance of power to prevent any nation—especially France or Russia—from dominating Europe.[52][53]

Palmerston cooperated with France when necessary for the balance of power, but did not make permanent alliances with anyone. He tried to keep autocratic nations like Russia and Austria in check; he supported liberal regimes because they led to greater stability in the international system. However he also supported the autocratic Ottoman Empire because it blocked Russian expansion.[54] Second in importance to Palmerston was Lord Aberdeen, a diplomat, foreign minister and prime minister. Before the Crimean War debacle that ended his career he scored numerous diplomatic triumphs, starting in 1813–1814 when as ambassador to the Austrian Empire he negotiated the alliances and financing that led to the defeat of Napoleon. In Paris he normalized relations with the newly restored Bourbon government and convinced his government they could be trusted. He worked well with top European diplomats such as his friends Klemens von Metternich in Vienna and François Guizot in Paris. He brought Britain into the center of Continental diplomacy on critical issues, such as the local wars in Greece, Portugal and Belgium. Simmering troubles with the United States were ended by compromising the border dispute in Maine that gave most of the land to the Americans but gave Canada a strategically important link to a warm water port.[55] Aberdeen played a central role in winning the Opium Wars against China, gaining control of Hong Kong in the process.[56][57]

Belgian Revolution

Catholic Belgians in 1830 broke away from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and established an independent Kingdom of Belgium.[58] They could not accept the Dutch's king's favouritism towards Protestantism and his disdain for the French language. Outspoken liberals regarded King William I's rule as despotic. There were high levels of unemployment and industrial unrest among the working classes. There was small-scale fighting but it took years before the Netherlands finally recognized defeat. In 1839 the Dutch accepted Belgian independence by signing the Treaty of London. The major powers guaranteed Belgian independence.[59][60]

Revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848 were a series of uncoordinated political upheavals throughout Europe in 1848. They attempted to overthrow reactionary monarchies. This was the most widespread revolutionary wave in European history. It reached most of Europe, but much less so in the Americas, Britain and Belgium, where liberalism was recently established. However the reactionary forces prevailed, especially with Russian help, and many rebels went into exile. There were some social reforms.[61]

The revolutions were essentially democratic and liberal in nature, with the aim of removing the old monarchical structures and creating independent nation states. The revolutions spread across Europe after an initial revolution began in France in February. Over 50 countries were affected. Liberal ideas had been in the air for a decade and activist from each country drew from the common pool, but they did not form direct links with revolutionaries in nearby countries.[62]

Key contributing factors were widespread dissatisfaction with old established political leadership, demands for more participation in government and democracy, demands for freedom of the press, other demands made by the working class, the upsurge of nationalism, and the regrouping of established government forces.[63] Liberalism at this time meant the replacement of autocratic governments by constitutional states under the rule of law. It had become the creed of the bourgeoisie, but they were not in power. It was the main factor in France. The main factor in the German, Italian and Austrian states was nationalism. Stimulated by the Romantic movement, nationalism had aroused numerous ethnic/language groups in their common past. Germans and Italians lived under multiple governments and demanded to be united in their own national state. Regarding the Austrian Empire, the many ethnicities suppressed by foreign rule—especially Hungarians—fought for a revolution.[64]

The uprisings were led by temporary coalitions of reformers, the middle classes and workers, which did not hold together for long. The start was in France, where large crowds forced king Louis Philippe I to abdicate. Across Europe came the sudden realization that it was indeed possible to destroy a monarchy. Tens of thousands of people were killed, and many more were forced into exile. Significant lasting reforms included the abolition of serfdom in Austria and Hungary, the end of absolute monarchy in Denmark, and the introduction of representative democracy in the Netherlands. The revolutions were most important in France, the Netherlands, the states of the German Confederation, Italy, and the Austrian Empire.[65]

Reactionary forces ultimately prevailed, aided by Russian military intervention in Hungary, and the strong traditional aristocracies and established churches. The revolutionary surge was sudden and unexpected, catching the traditional forces unprepared. But the revolutionaries were also unprepared – they had no plans on how to hold power when it was suddenly in their hands, and bickered endlessly. Reaction came much more gradually, but the aristocrats had the advantages of vast wealth, large networks of contacts, many subservient subjects, and the specific goal in mind of returning to the old status quo.[66]

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire was only briefly involved in the Napoleonic Wars through the French campaign in Egypt and Syria, 1798–1801. It was not invited to the Vienna Conference. During this period the Empire steadily weakened militarily, and lost most of its holdings in Europe (starting with Greece) and in North Africa (starting with Egypt). Its great enemy was Russia, while its chief supporter was Britain.[67][68]

As the 19th century progressed the Ottoman Empire grew weaker militarily and economically. It lost more and more control over local governments especially in Europe. It started borrowing large sums and went bankrupt in 1875. Britain increasingly became its chief ally and protector, even fighting the Crimean War against Russia in the 1850s to help it survive . Three British leaders played major roles. Lord Palmerston, who in the 1830–1865 era considered the Ottoman Empire an essential component in the balance of power, was the most favourable toward Constantinople. William Gladstone in the 1870s sought to build a Concert of Europe that would support the survival of the empire. In the 1880s and 1890s Lord Salisbury contemplated an orderly dismemberment of it, in such a way as to reduce rivalry between the greater powers.[69] The Berlin Conference on Africa of 1884 was, except for the abortive Hague Conference of 1899, the last great international political summit before 1914. Gladstone stood alone in advocating concerted instead of individual action regarding the internal administration of Egypt, the reform of the Ottoman empire, and the opening-up of Africa. Bismarck and Lord Salisbury rejected Gladstone’s position and were more representative of the consensus.[70]

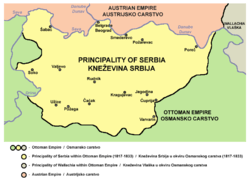

Serbian independence

A successful uprising against the Ottomans marked the foundation of modern Serbia.[71] The Serbian Revolution took place between 1804 and 1835, as this territory evolved from an Ottoman province into a constitutional monarchy and a modern Serbia. The first part of the period, from 1804 to 1815, was marked by a violent struggle for independence with two armed uprisings. The later period (1815–1835) witnessed a peaceful consolidation of political power of the increasingly autonomous Serbia, culminating in the recognition of the right to hereditary rule by Serbian princes in 1830 and 1833 and the territorial expansion of the young monarchy.[72] The adoption of the first written Constitution in 1835 abolished feudalism and serfdom,[73] and made the country suzerain.[74]

Crimean War

The Crimean War (1853–1856) was fought between Russia on the one hand and an alliance of Great Britain, France, Sardinia, and the Ottoman Empire on the other. Russia was defeated.[75][76]

In 1851, France under Emperor Napoleon III compelled the Sublime Porte (the Ottoman government ) to recognize it as the protector of Christian sites in the Holy Land. Russia denounced this claim, since it claimed to be the protector of all Eastern Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire. France sent its fleet to the Black Sea; Russia responded with its own show of force. In 1851, Russia sent troops into the Ottoman provinces of Moldavia and Wallachia. Britain, now fearing for the security of the Ottoman Empire, sent a fleet to join with the French expecting the Russians would back down. Diplomatic efforts failed. The Sultan declared war against Russia in October 1851. Following an Ottoman naval disaster in November, Britain and France declared war against Russia. Most of the battles took place in the Crimean peninsula, which the Allies finally seized.[77]

Russia was defeated and was forced to accept the Treaty of Paris, signed on 30 March 1856, ending the war. The Powers promised to respect Ottoman independence and territorial integrity. Russia gave up a little land and relinquished its claim to a protectorate over the Christians in the Ottoman domains. In a major blow to Russian power and prestige, the Black Sea was demilitarized, and an international commission was set up to guarantee freedom of commerce and navigation on the Danube River. Moldavia and Wallachia remained under nominal Ottoman rule, but would be granted independent constitutions and national assemblies.[78]

New rules of wartime commerce were set out: (1) privateering was illegal; (2) a neutral flag covered enemy goods except contraband; (3) neutral goods, except contraband, were not liable to capture under an enemy flag; (4) a blockade, to be legal, had to be effective.[79]

The war helped modernize warfare by introducing major new technologies such as railways, the telegraph, and modern nursing methods. In the long run the war marked a turning point in Russian domestic and foreign policy. Russia's military demonstrated its weakness, its poor leadership, and its lack of modern weapons and technology. Russia's weak economy was unable to fully support its military adventures, so in the future it redirected its attention to much weaker Muslim areas in central Asia, and left Europe alone. Russian intellectuals used the humiliating defeat to demand fundamental reform of the government and social system. The war weakened both Russia and Austria, so they could no longer promote stability. This opened the way for Napoleon III, Cavour (in Italy) and Otto von Bismarck (in Germany) to launch a series of wars in the 1860s that reshaped Europe.[80][81]

Moldavia and Wallachia

In a largely peaceful transition, the Ottoman provinces of Moldavia and Wallachia broke away slowly, achieved effective autonomy by 1859, and finally became officially an independent nation in 1878. The two provinces had long been under Ottoman control, but both Russia and Austria also wanted them, making the region a site of conflict in the 19th century. The population was largely Orthodox in religion and spoke Romanian, but there were many minorities, such as Jews and Greeks. The provinces were occupied by Russia after the Treaty of Adrianople in 1829. Russian and Turkish troops combined to suppress the Wallachian Revolution of 1848. During the Crimean War Austria took control. The population decided on unification on the basis of historical, cultural and ethnic connections. It took effect in 1859 after the double election of Alexandru Ioan Cuza as Ruling Prince of the United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia (renamed of Romania in 1862).[82]

With Russian sponsorship, Romania officially became independent in 1878.[83] It focused its attention on Transylvania, the historical region of Hungary with about two million Romanians. Finally when the Austro-Hungarian Empire collapsed at the end of the First World War, Romania obtained Transylvania.[84]

1860–1871: Nationalism and unification

The force of nationalism grew dramatically in the early and middle 19th century, involving a realization of cultural identity among the people sharing the same language and religious heritage. It was strong in the established countries, and was a powerful force for demanding more unity with or independence from Germans, Irish, Italians, Greeks, and the Slavic peoples of southeastern Europe. The strong sense of nationalism also grew in established independent nations, such as Britain and France. English historian J. P. T. Bury argues:

- Between 1830 and 1870 nationalism had thus made great strides. It had inspired great literature, quickened scholarship and nurtured heroes. It had shown its power both to unify and to divide. It had led to great achievements of political construction and consolidation in Germany and Italy ; but it was more clearly than ever a threat to the Ottoman and Habsburg empires, which were essentially multi-national. European culture had been enriched by the new vernacular contributions of little-known or forgotten peoples, but at the same time such unity as it had was imperilled by fragmentation. Moreover, the antagonisms fostered by nationalism had made not only for wars, insurrections, and local hatreds —^they had accentuated or created new spiritual divisions in a nominally Christian Europe.[85]

Great Britain

In 1859, following another short-lived Conservative government, Prime Minister Lord Palmerston and Earl Russell made up their differences, and Russell consented to serve as Foreign Secretary in a new Palmerston cabinet. It was the first true Liberal Cabinet. This period was a particularly eventful one in the world, seeing the Unification of Italy,[86] the American Civil War,[87] and the 1864 war over Schleswig-Holstein between Denmark and the German states.[88] Russell and Palmerston were tempted to intervene on the side of the Confederacy in the American Civil War, but they kept Britain neutral in every case.[89]

France

Despite his promises in 1852 of a peaceful reign, Napoleon III could not resist the temptations of glory in foreign affairs.[90] He was visionary, mysterious and secretive; he had a poor staff, and kept running afoul of his domestic supporters. In the end he was incompetent as a diplomat.[91] After a brief threat of an invasion of Britain in 1851, France and Britain cooperated in the 1850s, with an alliance in the Crimean War, and a major trade treaty in 1860. However, Britain viewed the Second Empire of Napoleon III with increasing distrust, especially as the emperor built up his navy, expanded his empire and took up a more active foreign policy.[92]

Napoleon III did score some successes: he strengthened French control over Algeria, established bases in Africa, began the takeover of Indochina, and opened trade with China. He facilitated a French company building the Suez Canal, which Britain could not stop. In Europe, however, Napoleon failed again and again. The Crimean war of 1854–1856 produced no gains. War with Austria in 1859 facilitated the unification of Italy, and Napoleon was rewarded with the annexation of Savoy and Nice. The British grew annoyed at his intervention in Syria in 1860–61. He angered Catholics alarmed at his poor treatment of the Pope, then reversed himself and angered the anticlerical liberals at home and his erstwhile Italian allies. He lowered the tariffs, which helped in the long run but in the short run angered owners of large estates and the textile and iron industrialists, while leading worried workers to organize. Matters grew worse in the 1860s as Napoleon nearly blundered into war with the United States in 1862, while his Mexican intervention in 1861–1867 was a total disaster. Finally in the end he went to war with Prussia in 1870 when it was too late to stop the unification of all Germans, aside from Austria, under the leadership of Prussia. Napoleon had alienated everyone; after failing to obtain an alliance with Austria and Italy, France had no allies and was bitterly divided at home. It was disastrously defeated on the battlefield, losing Alsace and Lorraine. A. J. P. Taylor is blunt: "he ruined France as a great power".[93][94]

Italian unification

The Risorgimento was the era from 1848 to 1871 that saw the achievement of independence of the Italians from Austrian Habsburgs in the north and the Spanish Bourbons in the south, securing national unification. Piedmont (known as the Kingdom of Sardinia) took the lead and imposed its constitutional system on the new nation of Italy.[95][96][97][98]

The papacy secured French backing to resist unification, fearing that giving up control of the Papal States would weaken the Church and allow the liberals to dominate conservative Catholics.[99] The newly united Italy was recognized as the sixth great power.[100]

United States

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), the Southern slave states attempted to secede from the Union and set up an independent country, the Confederate States of America. The North would not accept this affront of American nationalism, and fought to restore the Union.[101] British and French aristocratic leaders personally disliked American republicanism and favoured the more aristocratic Confederacy. The South was also by far the chief source of cotton for European textile mills. The goal of the Confederacy was to obtain British and French intervention, that is, war against the Union. Confederates believed (with scant evidence) that "cotton is king" – that is, cotton was so essential to British and French industry that they would fight to get it. The Confederates did raise money in Europe, which they used to buy warships and munitions. However Britain had a large surplus of cotton in 1861; stringency did not come until 1862. Most important was the dependence on grain from the U.S. North for a large portion of the British food supply, France would not intervene alone, and in any case was less interested in cotton than in securing its control of Mexico. The Confederacy would allow that if it secured its independence, but the Union never would approve.[102] Washington made it clear that any official recognition of the Confederacy meant war with the U.S.[103]

Queen Victoria's husband Prince Albert helped defuse a war scare in late 1861. The British people generally favored the United States. What little cotton was available came from New York City, as the blockade by the U.S. Navy shut down 95% of Southern exports to Britain. In September 1862, during the Confederate invasion of Maryland, Britain (along with France) contemplated stepping in and negotiating a peace settlement, which could only mean war with the United States. But in the same month, US president Abraham Lincoln announced the Emancipation Proclamation. Since support of the Confederacy now meant support for slavery, there was no longer any possibility of European intervention.[104]

Meanwhile, the British sold arms to both sides, built blockade runners for a lucrative trade with the Confederacy, and surreptitiously allowed warships to be built for the Confederacy.[105] The warships caused a major diplomatic row that was resolved in the Alabama Claims in 1872, in the Americans' favor.[106]

Germany

.jpg)

Prussia, under the leadership of Otto von Bismarck, took the lead in uniting all of Germany (except for Austria), and created a new German Empire, headed by the king of Prussia. To do it, he engaged in a series of short, decisive wars with Denmark, Austria and France. The many smaller German states followed the lead of Prussia, until finally they united together after defeating France in 1871. Bismarck's Germany then became the most powerful and dynamic state in Europe, and Bismarck himself promoted decades of peace in Europe.[107]

Schleswig and Holstein

A major diplomatic row, and several wars, emerged from the very complex situation in Schleswig and Holstein, where Danish and German claims collided, and Austria and France became entangled. The Danish and German duchies of Schleswig-Holstein were, by international agreement, ruled by the king of Denmark but were not legally part of Denmark. An international treaty provided that the two territories were not to be separated from each other, though Holstein was part of the German Confederation. In the late 1840s, with both German and Danish nationalism on the rise, Denmark attempted to incorporate Schleswig into its kingdom. The first war was a Danish victory. The Second Schleswig War of 1864 was a Danish defeat at the hands of Prussia and Austria.[108][109]

Unification

Berlin and Vienna split control of the two territories. That led to conflict between them, resolved by the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, which Prussia quickly won, thus becoming the leader of the German-speaking peoples. Austria now dropped to the second rank among the Great Powers.[110] Emperor Napoleon III of France could not tolerate the rapid rise of Prussia, and started the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 over perceived insults and other trivialities. The spirit of German nationalism caused the smaller German states (such as Bavaria and Saxony) to join the war alongside Prussia. The German coalition won an easy victory, dropping France to second class status among the Great Powers. Prussia, under Otto von Bismarck, then brought together almost all the German states (excluding Austria, Luxembourg and Liechtenstein) into a new German Empire. Bismarck's new empire became the most powerful state in continental Europe until 1914.[111][112] Napoleon III was overconfident in his military strength and failed to stop the rush to war when he was unable to find allies who would support a war to stop German unification.[113]

1871: the year of transition

Maintaining the peace

After fifteen years of warfare in the Crimea, Germany and France, Europe began a period of peace in 1871.[114][115] With the founding of the German Empire and the signing of the Treaty of Frankfurt (10 May 1871), Otto von Bismarck emerged as a decisive figure in European history from 1871 to 1890. He retained control over Prussia and as well as the foreign and domestic policies of the new German Empire. Bismarck had built his reputation as a war-maker but changed overnight into a peacemaker. He skillfully used balance of power diplomacy to maintain Germany's position in a Europe which, despite many disputes and war scares, remained at peace. For historian Eric Hobsbawm, it was Bismarck who "remained undisputed world champion at the game of multilateral diplomatic chess for almost twenty years after 1871, [and] devoted himself exclusively, and successfully, to maintaining peace between the powers".[116] Historian Paul Knaplund concludes:

- A net result of the strength and military prestige of Germany combined with situations created or manipulated by her chancellor was that in the eighties Bismarck became the umpire in all serious diplomatic disputes, whether they concerned Europe, Africa, or Asia. Questions such as the boundaries of Balkan states, the treatment of Armenians in the Turkish empire and of Jews in Rumania, the financial affairs of Egypt, Russian expansion in the Middle East, the war between France and China, and the partition of Africa had to be referred to Berlin; Bismarck held the key to all these problems.[117]

Bismarck's main mistake was giving in to the Army and to intense public demand in Germany for acquisition of the border provinces of Alsace and Lorraine, thereby turning France into a permanent, deeply-committed enemy (see French–German enmity). Theodore Zeldin says, "Revenge and the recovery of Alsace-Lorraine became a principal object of French policy for the next forty years. That Germany was France's enemy became the basic fact of international relations."[118] Bismarck's solution was to make France a pariah nation, encouraging royalty to ridicule its new republican status, and building complex alliances with the other major powers – Austria, Russia, and Britain – to keep France isolated diplomatically.[119][120] A key element was the League of the Three Emperors, in which Bismarck brought together rulers in Berlin, Vienna and St. Petersburg to guarantee each other's security, while blocking out France; it lasted 1881–1887.[121][122]

Major powers

Britain had entered an era of "splendid isolation", avoiding entanglements that had led it into the unhappy Crimean War in 1854–1856. It concentrated on internal industrial development and political reform, and building up its great international holdings, the British Empire, while maintaining by far the world's strongest Navy to protect its island home and its many overseas possessions. It had come dangerously close to intervening in the American Civil War in 1861–1862, and in May 1871 it signed the Treaty of Washington with the United States that put into arbitration the American claims that the lack of British neutrality had prolong the war; arbitrators eventually awarded the United States $15 million.[123] Russia took advantage of the Franco-Prussian war to renounce the 1856 treaty in which it had been forced to demilitarize the Black Sea. Repudiation of treaties was unacceptable to the powers, so the solution was a conference in January 1871 at London that formally abrogated key elements of the 1856 treaty and endorsed the new Russian action. Russia had always wanted control of Constantinople and the straits that connected the Black Sea to the Mediterranean and would nearly achieve that in the First World War.[124] France had long stationed an army in Rome to protect the pope; it recalled the soldiers in 1870, and the Kingdom of Italy moved in, seized the remaining papal territories, and made Rome its capital city in 1871 ending the risorgimento. Italy was finally unified, but at the cost of alienating the pope and the Catholic community for a half century; the unstable situation was resolved in 1929 with the Lateran Treaties.[125]

Conscription

A major trend was the move away from a professional army to a Prussian system that combined a core of professional careerists, a rotating base of conscripts, who after a year or two of active duty moved into a decade or more of reserve duty with a required summer training program every year. Training took place in peacetime, and in wartime a much larger, well-trained, fully staffed army could be mobilized very quickly. Prussia had started in 1814, and the Prussian triumphs of the 1860s made its model irresistible. The key element was universal conscription, with relatively few exemptions. The upper strata was drafted into the officer corps for one year's training, but was nevertheless required to do its full reserve duty along with everyone else. Austria adopted the system in 1868 (shortly after its defeat by Prussia) and France In 1872 (shortly after its defeat by Prussia and other German states). Japan followed in 1873, Russia in 1874, and Italy in 1875. All major countries adopted conscription by 1900, except for Great Britain and the United States. By then peacetime Germany had an army of 545,000, which could be expanded in a matter of days to 3.4 million by calling up the reserves. The comparable numbers in France were 1.8 million and 3.5 million; Austria, 1.1 million and 2.6 million; Russia, 1.7 million to 4 million. The new system was expensive, with a per capita cost of the forces doubling or even tripling between 1870 and 1914. By then total defense spending averaged about 5% of the national income. Nevertheless, taxpayers seemed satisfied; parents were especially impressed with the dramatic improvements shown in the immature boys they sent away at age 18, compared to the worldly-wise men who returned two years later.[126]

Imperialism

Most of the major powers (and some minor ones such as Belgium, the Netherlands and Denmark) engaged in imperialism, building up their overseas empires especially in Africa and Asia. Although there were numerous insurrections, historians count only a few wars, and they were small-scale: two Anglo-Boer Wars (1880–1881 and 1899–1902), the Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), First Italo-Ethiopian War (1895–96), Spanish–American War (1898), and Italo-Ottoman war (1911). The largest was the Russo-Japanese War of 1905, the only in which two major powers fought each other.[127]

Among the main empires from 1875 to 1914, historians assess a mixed record in terms of profitability. The assumption was that colonies would provide an excellent captive market for manufactured items. Apart from India, this was seldom true. By the 1890s, imperialists gained economic benefit primarily in the production of inexpensive raw materials to feed the domestic manufacturing sector. Overall, Great Britain profited well from India, but not from most of the rest of its empire. The Netherlands did very well in the East Indies. Germany and Italy got very little trade or raw materials from their empires. France did slightly better. The Belgian Congo was notoriously profitable when it was a capitalistic rubber plantation owned and operated by King Leopold II as a private enterprise. However, scandal after scandal regarding badly mistreated labour led the international community to force the government of Belgium to take it over in 1908, and it became much less profitable. The Philippines cost the United States much more than expected.[128]

The world's colonial population at the time of the First World War totaled about 560 million people, of whom 70.0% were in British domains, 10.0% in French, 8.6% in Dutch, 3.9% in Japanese, 2.2% in German, 2.1% in American, 1.6% in Portuguese, 1.2% in Belgian and 0.5% in Italian possessions. The home domains of the colonial powers had a total population of about 370 million people.[129]

French Empire in Asia and Africa

France seizes Mexico

Napoleon III took advantage of the American Civil War to attempt to take control of Mexico and impose its own puppet Emperor Maximilian.[130] France, Spain, and Britain, angry over unpaid Mexican debts, sent a joint expeditionary force that seized the Veracruz customs house in Mexico in December 1861. Spain and Britain soon withdrew after realizing that Napoleon III intended to overthrow the Mexican government under elected president Benito Juárez and establish a Second Mexican Empire. Napoleon had the support of the remnants of the Conservative elements that Juarez and his Liberals had defeated in the Reform War, a civil war from 1857–61. In the French intervention in Mexico in 1862. Napoleon installed Austrian archduke Maximilian of Habsburg as emperor of Mexico. Juárez rallied opposition to the French; Washington supported Juárez and refused to recognize the new government because it violated the Monroe Doctrine. After its victory over the Confederacy in 1865, the U.S. sent 50,000 experienced combat troops to the Mexican border to make clear its position. Napoleon was stretched very thin; he had committed 40,000 troops to Mexico, 20,000 to Rome to guard the Pope against the Italians, and another 80,000 in restive Algeria. Furthermore, Prussia, having just defeated Austria, was an imminent threat. Napoleon realized his predicament and withdrew all his forces from Mexico in 1866. Juarez regained control and executed the hapless emperor.[131][132][133]

The Suez Canal, initially built by the French, became a joint British-French project in 1875, as both considered it vital to maintaining their influence and empires in Asia. In 1882, ongoing civil disturbances in Egypt prompted Britain to intervene, extending a hand to France. France's leading expansionist Jules Ferry was out of office, and the government allowed Britain to take effective control of Egypt.[134]

Takeover of Egypt, 1882

The most decisive event emerged from the Anglo-Egyptian War, which resulted in the British occupation of Egypt for seven decades, even though the Ottoman Empire retained nominal ownership until 1914.[135] France was seriously unhappy, having lost control of the canal that it built and financed and had dreamed of for decades. Germany, Austria, Russia, and Italy – and of course the Ottoman Empire itself-- were all angered by London's unilateral intervention.[136] Historian A.J.P. Taylor says that this "was a great event; indeed, the only real event in international relations between the Battle of Sedan and the defeat of Russia in the Russo-Japanese war."[137] Taylor emphasizes the long-term impact:

- The British occupation of Egypt altered the balance of power. It not only gave the British security for their route to India; it made them masters of the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East; it made it unnecessary for them to stand in the front line against Russia at the Straits....And thus prepared the way for the Franco-Russian Alliance ten years later.[138]

Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone and his Liberal Party had a reputation for strong opposition to imperialism, so historians have long debated the explanation for this sudden reversal of policy.[139] The most influential was study by John Robinson and Ronald Gallagher, Africa and the Victorians (1961), which focused on The Imperialism of Free Trade and was promoted by the Cambridge School of historiography. They argue there was no long-term Liberal plan in support of imperialism, but the urgent necessity to act to protect the Suez Canal was decisive in the face of what appeared to be a radical collapse of law and order, and a nationalist revolt focused on expelling the Europeans, regardless of the damage it would do to international trade and the British Empire. A complete takeover of Egypt, turning it into a British colony like India was much too dangerous for it would be the signal for the powers to rush in for the spoils of the tottering Ottoman Empire, with a major war a likely result.[140][141]

Gladstone's decision came against strained relations with France, and maneuvering by "men on the spot" in Egypt. Critics such as Cain and Hopkins have stressed the need to protect large sums invested by British financiers and Egyptian bonds, while downplaying the risk to the viability of the Suez Canal. Unlike the Marxists, they stress "gentlemanly" financial and commercial interests, not the industrial, capitalism that Marxists believe was always central.[142] More recently, specialists on Egypt have been interested primarily in the internal dynamics among Egyptians that produce the failed Urabi Revolt.[143][144]

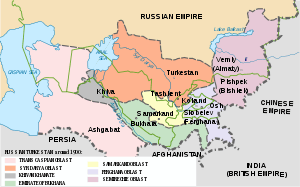

Great Game in Central Asia

The "Great Game" was a political and diplomatic confrontation that existed for most of the nineteenth century between Britain and Russia over Afghanistan and neighbouring territories in Central and Southern Asia, especially Persia (Iran) and Turkestan.[145] Britain made it a high priority to protect all the approaches to India, and the "great game" is primarily how the British did this in terms of a possible Russian threat. Russia itself had no plans involving India and repeatedly said so.[146] This resulted in an atmosphere of distrust and the constant threat of war between the two empires. There were numerous local conflicts, but a war in central Asia between the two powers never happened.[147]

Bismarck realized that both Russia and Britain considered control of central Asia a high priority, dubbed the "Great Game". Germany had no direct stakes, however its dominance of Europe was enhanced when Russian troops were based as far away from Germany as possible. Over two decades, 1871–1890, he maneuvered to help the British, hoping to force the Russians to commit more soldiers to Asia.[148]

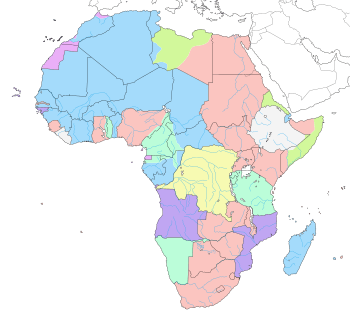

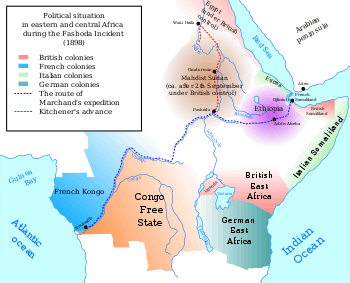

Scramble for Africa

The "scramble for Africa" was launched by Britain's unexpected takeover of Egypt in 1882. In response, it became a free-for-all for the control of the rest of Africa, as Britain, France, Germany, Italy and Portugal all greatly expanded their colonial empires in Africa. The King of Belgium personally controlled the Congo. Bases along the coast become the nucleus of colonies that stretched inland.[149] In the 20th century, the scramble for Africa was widely denounced by anti-imperialist spokesmen. At the time, however, it was praised as a solution to the terrible violence and exploitation caused by Unrestrained adventurers, slave traders, and exploiters.[150] Bismarck took the lead in trying to stabilize the situation by the Berlin Conference of 1884–1885. All the European powers agreed on ground rules to avoid conflicts in Africa.[151]

In British colonies, workers and businessmen from India were brought in to build railways, plantations and other enterprises. Britain immediately applied the administrative lessons that had been learned in India to Egypt and the other new African colonies.[152]

Tensions between Britain and France reached tinder stage in Africa. At several points war was possible, but never happened.[153] The most serious episode was the Fashoda Incident of 1898. French troops tried to claim an area in the Southern Sudan, and a British force purporting to be acting in the interests of the Khedive of Egypt arrived to confront them. Under heavy pressure the French withdrew securing Anglo-Egyptian control over the area. The status quo was recognised by an agreement between the two states acknowledging British control over Egypt, while France became the dominant power in Morocco, but France experienced a serious disappointment.[154][155]

The Ottoman Empire lost its nominal control over Algeria, Tunisia and Libya. It retained only nominal control of Egypt. In 1875 Britain purchased the Suez canal shares from the almost bankrupt khedive of Egypt, Isma'il Pasha.

Kenya

The experience of Kenya is representative of the colonization process in East Africa. By 1850 European explorers had begun mapping the interior. Three developments encouraged European interest in East Africa. First was the emergence of the island of Zanzibar, located off the east coast. It became a base from which trade and exploration of the African mainland could be mounted.[156]

By 1840, to protect the interests of the various nationals doing business in Zanzibar, consul offices had been opened by the British, French, Germans and Americans. In 1859, the tonnage of foreign shipping calling at Zanzibar had reached 19,000 tons. By 1879, the tonnage of this shipping had reached 89,000 tons. The second development spurring European interest in Africa was the growing European demand for products of Africa including ivory and cloves. Thirdly, British interest in East Africa was first stimulated by their desire to abolish the slave trade.[157] Later in the century, British interest in East Africa was stimulated by German competition, and in 1887 the Imperial British East Africa Company, a private concern, leased from Seyyid Said his mainland holdings, a 10-mile (16-km)-wide strip of land along the coast.

Germany set up a protectorate over the Sultan of Zanzibar's coastal possessions in 1885. It traded its coastal holdings to Britain in 1890, in exchange for German control over the coast of Tanganyika.

In 1895 the British government claimed the interior as far west as Lake Naivasha; it set up the East Africa Protectorate. The border was extended to Uganda in 1902, and in 1920 most of the enlarged protectorate became a crown colony. With the beginning of colonial rule in 1895, the Rift Valley and the surrounding Highlands became the enclave of white immigrants engaged in large-scale coffee farming dependent on mostly Kikuyu labour. There were no significant mineral resources—none of the gold or diamonds that attracted so many to South Africa. In the initial stage of colonial rule, the administration relied on traditional communicators, usually chiefs. When colonial rule was established and efficiency was sought, partly because of settler pressure, newly educated younger men were associated with old chiefs in local Native Councils.[158]

Following severe financial difficulties of the British East Africa Company, the British government on 1 July 1895 established direct rule through the East African Protectorate, subsequently opening (1902) the fertile highlands to white settlers. A key to the development of Kenya's interior was the construction, started in 1895, of a railway from Mombasa to Kisumu, on Lake Victoria, completed in 1901. Some 32,000 workers were imported from British India to do the manual labour. Many stayed, as did most of the Indian traders and small businessmen who saw opportunity in the opening up of the interior of Kenya.[159]

Portugal

Portugal, a small poor agrarian nation with a strong seafaring tradition, built up a large empire, and kept it longer than anyone else by avoiding wars and remaining largely under the protection of Britain. In 1899 it renewed its Treaty of Windsor with Britain originally written in 1386.[160] Energetic explorations in the sixteenth century led to a settler colony in Brazil. Portugal also established trading stations open to all nations off the coasts of Africa, South Asia, and East Asia. Portugal had imported slaves as domestic servants and farm workers in Portugal itself, and used its experience to make slave trading a major economic activity. Portuguese businessmen set up slave plantations on the nearby islands of Madeira, Cape Verde, and the Azores, focusing on sugar production. In 1770, the enlightened despot Pombal declared trade to be a noble and necessary profession, allowing businessmen to enter the Portuguese nobility. Many settlers moved to Brazil, which became independent in 1822.[161][162]

After 1815, the Portuguese expanded their trading ports along the African coast, moving inland to take control of Angola and Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique). The slave trade was abolished in 1836, in part because many foreign slave ships were flying the Portuguese flag. In India, trade flourished in the colony of Goa, with its subsidiary colonies of Macau, near Hong Kong on the China coast, and Timor, north of Australia. The Portuguese successfully introduced Catholicism and the Portuguese language into their colonies, while most settlers continued to head to Brazil.[163][164]

Italy

Italy was often called the Least of the Great Powers for its weak industry and weak military. In the Scramble for Africa of the 1880s, leaders of the new nation of Italy were enthusiastic about acquiring colonies in Africa, expecting it would legitimize their status as a power and help unify the people. In North Africa Italy first turned to Tunis, under nominal Ottoman control, where many Italian farmers had settled. Weak and diplomatically isolated, Italy was helpless and angered when France assumed a protectorate over Tunis in 1881. Turning to East Africa, Italy tried to conquer independent Ethiopia, but was massively defeated at the Battle of Adwa in 1896. Public opinion was angered at the national humiliation by an inept government. In 1911 the Italian people supported the seizure of what is now Libya.[165]

Italian diplomacy over a twenty-year period succeeded in getting permission to seize Libya, with approval coming from Germany, France, Austria, Britain and Russia. A centerpiece of the Italo-Turkish War of 1911–12 came when Italian forces took control of a few coastal cities against stiff resistance by Ottoman troops as well as the local tribesmen. After the peace treaty gave Italy control it sent in Italian settlers, but suffered extensive casualties in its brutal campaign against the tribes.[166]

Japan becomes a power

Starting in the 1860s Japan rapidly modernized along Western lines, adding industry, bureaucracy, institutions and military capabilities that provided the base for imperial expansion into Korea, China, Taiwan and islands to the south.[167] It saw itself vulnerable to aggressive Western imperialism unless it took control of neighboring areas. It took control of Okinawa and Formosa. Japan's desire to control Taiwan, Korea and Manchuria, led to the first Sino-Japanese War with China in 1894–1895 and the Russo-Japanese War with Russia in 1904–1905. The war with China made Japan the world's first Eastern, modern imperial power, and the war with Russia proved that a Western power could be defeated by an Eastern state. The aftermath of these two wars left Japan the dominant power in the Far East with a sphere of influence extending over southern Manchuria and Korea, which was formally annexed as part of the Japanese Empire in 1910.[168]

Okinawa

Okinawa island is the largest of the Ryukyu Islands, and paid tribute to China from the late 14th century. Japan took control of the entire Ryukyu island chain in 1609 and formally incorporated it into Japan in 1879.[169]

War with China

Friction between China and Japan arose from the 1870s from Japan's control over the Ryukyu Islands, rivalry for political influence in Korea and trade issues.[170] Japan, having built up a stable political and economic system with a small but well-trained army and navy, easily defeated China in the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894. Japanese soldiers massacred the Chinese after capturing Port Arthur on the Liaotung Peninsula. In the harsh Treaty of Shimonoseki of April 1895, China recognize the independence of Korea, and ceded to Japan Formosa, the Pescatores Islands and the Liaotung Peninsula. China further paid an indemnity of 200 million silver taels, opened five new ports to international trade, and allowed Japan (and other Western powers) to set up and operate factories in these cities. However, Russia, France, and Germany saw themselves disadvantaged by the treaty and in the Triple Intervention forced Japan to return the Liaotung Peninsula in return for a larger indemnity. The only positive result for China came when those factories led the industrialization of urban China, spinning off a local class of entrepreneurs and skilled mechanics.[171]

Taiwan

The island of Formosa (Taiwan) had an indigenous population when Dutch traders in need of an Asian base to trade with Japan and China arrived in 1623. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) built Fort Zeelandia. They soon began to rule the natives. China took control in the 1660s, and sent in settlers. By the 1890s there were about 2.3 million Han Chinese and 200,000 members of indigenous tribes. After its victory in the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894–95, the peace treaty ceded the island to Japan. It was Japan's first colony.[172]

Japan expected far more benefits from the occupation of Taiwan than the limited benefits it actually received. Japan realized that its home islands could only support a limited resource base, and it hoped that Taiwan, with its fertile farmlands, would make up the shortage. By 1905, Taiwan was producing rice and sugar and paying for itself with a small surplus. Perhaps more important, Japan gained Asia-wide prestige by being the first non-European country to operate a modern colony. It learned how to adjust its German-based bureaucratic standards to actual conditions, and how to deal with frequent insurrections. The ultimate goal was to promote Japanese language and culture, but the administrators realized they first had to adjust to the Chinese culture of the people. Japan had a civilizing mission, and it opened schools so that the peasants could become productive and patriotic manual workers. Medical facilities were modernized, and the death rate plunged. To maintain order, Japan installed a police state that closely monitored everyone. In 1945, Japan was stripped of its empire and Taiwan was returned to China.[173]

Japan defeats Russia, 1904–1905

Japan felt humiliated when the spoils from its decisive victory over China were partly reversed by the Western Powers (including Russia), which revised the Treaty of Shimonoseki. The Boxer Rebellion of 1899–1901 saw Japan and Russia as allies who fought together against the Chinese, with Russians playing the leading role on the battlefield.[174] In the 1890s Japan was angered at Russian encroachment on its plans to create a sphere of influence in Korea and Manchuria. Japan offered to recognize Russian dominance in Manchuria in exchange for recognition of Korea as being within the Japanese sphere of influence. Russia refused and demanded Korea north of the 39th parallel to be a neutral buffer zone between Russia and Japan. The Japanese government decided on war to stop the perceived Russian threat to its plans for expansion into Asia.[175] The Japanese Navy opened hostilities by launching surprise attacks on the Russian Eastern Fleet at Port Arthur, China. Russia suffered multiple defeats but Tsar Nicholas II fought on with the expectation that Russia would win decisive naval battles. When that proved illusory he fought to preserve the dignity of Russia by averting a "humiliating peace". The complete victory of the Japanese military surprised world observers. The consequences transformed the balance of power in East Asia, resulting in a reassessment of Japan's recent entry onto the world stage. It was the first major military victory in the modern era of an Asian power over a European one.[176]

Korea

In 1905, the Empire of Japan and the Korean Empire signed the Eulsa Treaty, which brought Korea into the Japanese sphere of influence as a protectorate. The Treaty was a result of the Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War and Japan wanting to increase its hold over the Korean Peninsula. The Eulsa Treaty led to the signing of the 1907 Treaty two years later. The 1907 Treaty ensured that Korea would act under the guidance of a Japanese resident general and Korean internal affairs would be under Japanese control. Korean Emperor Gojong was forced to abdicate in favour of his son, Sunjong, as he protested Japanese actions in the Hague Conference. Finally in 1910, the Annexation Treaty formally annexed Korea to Japan.[177]

Dividing up China

Officially, China remained a unified country. In practice, European powers and Japan took effective control of certain port cities and their surrounding areas from the middle nineteenth century until the 1920s.[178] Technically speaking, they exercised "extraterritoriality" that was imposed in a series of unequal treaties.[179][180]

In 1899–1900 the United States won international acceptance for the Open Door Policy whereby all nations would have access to Chinese ports, rather than having them reserved to just one nation.[181]

British policies

Free trade imperialism

Britain, in addition to taking control of new territories, developed an enormous power in economic and financial affairs in numerous independent countries, especially in Latin America and Asia. It lent money, built railways, and engaged in trade. The Great London Exhibition of 1851 clearly demonstrated Britain's dominance in engineering, communications and industry; that lasted until the rise of the United States and Germany in the 1890s.[182][183]

Splendid isolation

Historians agree that Lord Salisbury as foreign minister and prime minister 1885–1902 was a strong and effective leader in foreign affairs. He had a superb grasp of the issues, and proved:

- a patient, pragmatic practitioner, with a keen understanding of Britain's historic interests....He oversaw the partition of Africa, the emergence of Germany and the United States as imperial powers, and the transfer of British attention from the Dardanelles to Suez without provoking a serious confrontation of the great powers.[184]

In 1886–1902 under Salisbury, Britain continued its policy of Splendid isolation with no formal allies.[185][186] Lord Salisbury grew restless with the term in the 1890s, as his "third and final government found the policy of 'splendid isolation' increasingly less splendid," especially as France broke from its own isolation and formed an alliance with Russia.[187]

Policy toward Germany

Britain and Germany each tried to improve relations, but British distrust of the Kaiser for his recklessness ran deep. The Kaiser did indeed meddle in Africa in support of the Boers, which soured relations.[188]

The main accomplishment was a friendly 1890 treaty. Germany gave up its small Zanzibar colony in Africa and acquired the Heligoland islands, off Hamburg, which were essential to the security of Germany's ports.[189] Overtures toward friendship otherwise went nowhere, and a great Anglo-German naval arms race worsened tensions, 1880s-1910s.[190]

Liberal Party splits on imperialism

Liberal Party policy after 1880 was shaped by William Gladstone as he repeatedly attacked Disraeli's imperialism. The Conservatives took pride in their imperialism and it proved quite popular with the voters. A generation later, a minority faction of Liberals became active "Liberal Imperialists". The Second Boer War (1899 – 1902) was fought by Britain against and the two independent Boer republics of the Orange Free State and the South African Republic (called the Transvaal by the British). After a protracted hard-fought war, with severe hardships for Boer civilians, the Boers lost and were absorbed into the British Empire. The war bitterly divided with Liberals, with the majority faction denouncing it.[191] Joseph Chamberlain and his followers broke with the Liberal Party and formed an alliance with the Conservatives to promote imperialism.[192]

The Eastern Question

The Eastern Question from 1870 to 1914 was the imminent risk of a disintegration of the Ottoman Empire; often called "the sick man of Europe." Attention focused on rising nationalism among Christian ethnics in the Balkans, especially as supported by Serbia. There was a high risk this would lead to major confrontations between Austria-Hungary and Russia, and between Russian and Great Britain. Russia especially wanted control of Constantinople in the straits connecting the Black Sea with the Mediterranean. British policy had long been to support the Ottoman Empire against Russian expansion. However, In 1876 William Gladstone added a new dimension escalated the conflict by emphasizing Ottoman atrocities against Christians in Bulgaria. The atrocities - plus Ottoman attacks on Armenians, and Russian attacks on Jews -, attracted public attention across Europe and lessen the chances of quiet compromises.[193][194]

Long-term goals

Each of the countries paid close attention to its own long-term interests, usually in cooperation with its allies and friends.[195]

Ottoman Empire (Turkey)

The Ottoman Empire was hard-pressed by nationalistic movements among the Christian populations, As well as its laggard condition in terms of modern technology. After 1900, the large Arab population would also grow nationalistic. The threat of disintegration was real. Egypt for example although still nominally part of the Ottoman Empire, have been independent for century. Turkish nationalists were emerging, and the Young Turk movement indeed took over the Empire. While the previous rulers had been pluralistic, the Young Turks were hostile to all other nationalities and to non-Muslims. Wars were usually defeats, in which another slice of territory was sliced off and became semi-independent, including Greece, Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria, Romania, Bosnia, and Albania.[196]

Austro-Hungarian Empire

The Austro-Hungarian Empire, headquartered at Vienna, was a largely rural, poor, multicultural state. It was operated by and for the Habsburg family, who demanded loyalty to the throne, but not to the nation. Nationalistic movements were growing rapidly. The most powerful were the Hungarians, who preserved their separate status within the Habsburg Monarchy and with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, the creation of the Dual Monarchy they were getting practical equality. Other minorities, were highly frustrated, although some – especially the Jews – felt protected by the Empire. German nationalists, especially in the Sudetenland (part of Bohemia) however, looked to Berlin in the new German Empire.[197] There was a small German-speaking Austrian element located around Vienna, but it did not display much sense of Austrian nationalism. That is it did not demand an independent state, rather it flourished by holding most of the high military and diplomatic offices in the Empire. Russia was the main enemy, As well as Slavic and nationalist groups inside the Empire (especially in Bosnia-Herzegovina) and in nearby Serbia. Although Austria, Germany, and Italy had a defensive military alliance – the Triple Alliance – Italy was dissatisfied and wanted a slice of territory controlled by Vienna.

Gyula Andrássy after serving as Hungarian prime minister became Foreign Minister of Austria-Hungary (1871–1879). Andrássy was a conservative; his foreign policies looked to expanding the Empire into Southeast Europe, preferably with British and German support, and without alienating Turkey. He saw Russia as the main adversary, because of its own expansionist policies toward Slavic and Orthodox areas. He distrusted Slavic nationalist movements as a threat to his multi-ethnic empire.[198][199] As tensions escalated in the early 20th century Austria Foreign-policy was set in 1906–1912 by its powerful foreign minister Count Aehrenthal. He was thoroughly convinced that the Slavic minorities could never come together, and the Balkan League would never accomplish any damage to Austria. 1912 he rejected an Ottoman proposal for an alliance that would include Austria, Turkey and Romania. His policies alienated the Bulgarians, who turned instead to Russia and Serbia. Although Austria had no intention to embark on additional expansion to the south, Aehrenthal encouraged speculation to that effect, expecting it would paralyze the Balkan states. Instead, it incited them to feverish activity to create a defensive block to stop Austria. A series of grave miscalculations at the highest level thus significantly strengthened Austria's enemies.[200]

Russia

Russia was growing in strength, and wanted access to the warm waters of the Mediterranean. To get that it needed control of the Straits, connecting the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, and if possible, control of Constantinople, the capital of the Ottoman Empire. Slavic nationalism was strongly on the rise in the Balkans. It gave Russia the opportunity to protect Slavic and Orthodox Christians. This put it in sharp opposition to the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[201]

Serbia