Egypt–United States relations

Egypt–United States relations refers to the current and historical relationship between Egypt and the United States.

.jpg)

| |

Egypt |

United States |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Egyptian Embassy, Washington, D.C. | United States Embassy, Cairo |

The U.S. had minimal dealings with Egypt when it was controlled by the Ottoman Empire (before 1882) and Britain (1882–1945).

President Gamal Abdel Nasser (1956–70) antagonized the U.S. by his pro-Soviet policies and anti-Israeli rhetoric, but the U.S. helped keep him in power by forcing Britain and France to immediately end their invasion in 1956. American policy has been to provide strong support to governments that supported U.S. and Israeli interests in the region, especially presidents Anwar Sadat (1970–81) and Hosni Mubarak (1981–2011).

Between 1948 and 2011, the U.S. provided Egypt with $71.6 billion in bilateral military and economic aid.[1]

1950s

In 1956, the U.S. was alarmed at the closer ties between Egypt and the Soviet Union, and prepared the OMEGA Memorandum as a stick to reduce the regional power of President Gamal Abdel Nasser. When Egypt recognized Communist China, the U.S. ended talks about funding the Aswan Dam, a high prestige project much desired by Egypt. The dam was later built by the Soviet Union. When Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal in 1956, the Suez Crisis erupted with Britain and France threatening war to retake control of the canal and depose Nasser. Israel did invade the Suez in October 1956, and Britain and France (in league with Israel) sent in troops to seize the canal. Using heavy diplomatic and economic pressure, the Eisenhower administration forced Britain and France to withdraw soon, leading to a warming of relations between the U.S. and Egypt.[2]

1973–2011

After the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Egyptian foreign policy began to shift as a result of the change in Egypt's leadership from the fiery Nasser to the much more moderate Anwar Sadat and the emerging peace process between Egypt and Israel. Sadat realized that reaching a settlement of the Arab–Israeli conflict is a precondition for Egyptian development. To achieve this goal, Sadat ventured to enhance U.S.–Egyptian relations to foster a peace process with Israel. After a seven-year hiatus, both countries reestablished normal diplomatic relations on February 28, 1974.

Sadat asked Moscow for help, and Washington responded by offering more favorable of army's financial aid and technology. The advantages included Egypt's expulsion of 20,000 Soviet advisors and the reopening of the Suez Canal, and were seen by Nixon as "an investment in peace." [3][4]

Encouraged by Washington, Sadat opened negotiations with Israel, resulting most notably in the Camp David Accords brokered by President Jimmy Carter and made peace with Israel in a historic peace treaty in 1979.[5] Sadat's domestic policy, called 'Infitah,' was aimed at modernizing the economy and removing Nasser's heavy-handed controls. Sadat realized American aid was essential to that goal, and it allowed him to disengage from the Israeli conflict, and to pursue a regional peace policy.[6]

Military cooperation

Following the peace treaty with Israel, between 1979 and 2003, Egypt acquired about $19 billion in military aid, making Egypt the second largest non-NATO recipient of U.S. military aid after Israel. Also, Egypt received about $30 billion in economic aid within the same time frame. In 2009, the U.S. provided a military assistance of US$1.3 billion (inflation adjusted US$ 1.55 billion in 2020), and an economic assistance of US$250 million (inflation adjusted US$ 297.9 million in 2020).[7] In 1989 both Egypt and Israel became a Major non-NATO ally of the United States.

Military cooperation between the U.S. and Egypt is probably the strongest aspect of their strategic partnership. General Anthony Zinni, the former Commandant of the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM), once said, "Egypt is the most important country in my area of responsibility because of the access it gives me to the region." Egypt was also described during the Clinton Administration as the most prominent player in the Arab world and a key U.S. ally in the Middle East. U.S. military assistance to Egypt was considered part of the administration's strategy to maintaining continued availability of Persian Gulf energy resources and to secure the Suez Canal, which serves both as an important international oil route and a critical route for U.S. warships transiting between the Mediterranean and either the Indian Ocean or the Persian Gulf.

Egypt is the strongest military power on the African continent[8], and according to Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies' annual Middle East Strategic Balance, the largest in the Middle East

Counterterrorism

Despite differences and periods of friction in relations between the two countries, the U.S.–Egyptian relations under Mubarak had evolved, moving beyond the Middle East peace process towards an independent bilateral friendship. It was in the U.S. interest that Egypt was able to present moderate voice in Arab councils and persuade other Arab states to join the peace process and to normalize their relations with the U.S.

However lately Egyptian–American relations have become a little tense. This is due to a great extent to the Egyptian unwillingness to send troops to Afghanistan and Iraq in peace stabilization missions. Egypt strongly backed the U.S. in its war against international terrorism after the September 11th attacks of 2001 but refused to send troops to Afghanistan during the war and after it. Egypt also opposed U.S. military intervention of March 2003 in Iraq[9] through their membership in the African Union[10] and the Arab League[11], continued to oppose U.S. occupation of the country after the war and further refused to comply with U.S. requests to send troops to the country even under a UN umbrella.

The issue of participation in the post-war construction efforts in Iraq has been controversial in Egypt and in the Arab world as a whole. Opponents say that the war was illegal and it is necessary to wait until Iraq has legal representative government to deal with it. On the other hand, supporters of participation argued that the responsibility to protect Iraqis and to help them in time of crisis should prevail and guide the Egyptian action in Iraq, despite the fact that the Iraqis do not agree.

As of 2011, US officials quoted in USA Today described Egyptian security and military as having shared "valuable intelligence" and providing other "useful counterterrorism assistance", in the 1980, 90s and "particularly in the decade since the 9/11 attacks". Under President Hosni Mubarak and his intelligence chief Omar Suleiman, the U.S. has had "an important partnership" in counterterrorism.[12]

When the U.S. made cuts in military aid to Egypt following the overthrow of Mohamed Morsi and crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood movement, it continued funding for counterterrorism, border security and security operations in the Sinai Peninsula and Gaza Strip, considered very important to Israel's security.[13]

2011 Egyptian revolution and aftermath

.jpg)

During the 2011 Egyptian revolution top US government officials urged Hosni Mubarak and his government to reform, to refrain from using violence and to respect the rights of protesters such as the right to peaceful assembly and association. Ties between the two countries became strained after Egyptian soldiers and police raided 17 offices of local and foreign NGOs—including the International Republican Institute (IRI), the National Democratic Institute (NDI), Freedom House and the German Konrad-Adenauer Foundation on December 29, 2011 because of allegations of illegal funding from abroad.[14] The United States condemned the raids as an attack on democratic values[15] and threatened to stop the $1.3bn in military aid and about $250m in economic aid Washington gives Egypt every year,[16] but this threat was dismissed by the Egyptian government.[16] 43 NGO members[17] including Sam LaHood, son of U.S. Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood, and Nancy Okail, then resident director of U.S.-based NGO Freedom House's operations in Egypt, were charged with obtaining international funds illegally and failing to register with the Egyptian government.[18] After an appeal by those charged, the case had been switched from a criminal court to one handling misdemeanours, where the maximum penalty was a fine and not imprisonment.[19] After lifting a travel ban on 17 foreign NGO members,[19] among them 9 Americans,[19][20] the United States and Egypt began to repair their relations.[21] Nevertheless, on September 11, 2012, (the 11th anniversary of the September 11 attacks) Egyptian protesters stormed the US embassy in Cairo, tore down the American flag and replaced it with a flag with Islamic symbols,[22][23] to mock the Americans after an anti-Islamic movie denigrating the Islamic prophet, Muhammad, was shot in the United States and released on the internet.

In November 2012, Barack Obama—for the first time since Egypt signed the peace treaty with Israel—declared that the United States does not consider Egypt's Islamist-led government an ally or an enemy.[24][25][26] In another incident, General Martin Dempsey said that the U.S.–Egypt military ties will depend on Egypt's actions towards Israel. He said in June 2012; "The Egyptian leaders will salute a civilian president for the first time … and then they'll go back to barracks. But I don't think it's going to be as clean as that. That's why we want to stay engaged with them … not [to] shape or influence, but simply be there as a partner to help them understand their new responsibilities".[27]

Ties between the two countries have temporarily soured since the overthrow of Egyptian president Mohamed Morsi on July 3, 2013, which followed a massive uprising against Morsi.[28] The Obama administration denounced Egyptian attempts to combat the Muslim Brotherhood and its supporters, cancelling future military exercises and halting the delivery of F-16 jet fighters and AH-64 Apache attack helicopters to the Egyptian Armed Forces.[29] Popular sentiment among secular Egyptians towards the United States has been negatively affected by conspiracy theories which claim that the U.S. assisted the unpopular Muslim Brotherhood in attaining power [30][31][32][33]—as well as the Obama administration's policy of tolerance toward the Muslim Brotherhood and the past presidency of Morsi. However, in a 2014 news story, the BBC reported that "the US has revealed it has released $575 million (£338m) in military aid to Egypt that had been frozen since the ousting of President Mohammed Morsi last year."[34] In spite of President Trump's travel ban to neighboring and other Muslim-majority countries, the relations between Egypt and the United States are expected to be warm.[35]

Since 1987, Egypt has been receiving military aid at an average of $1.3 billion a year.[1][36]

In April 2019, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo warned Egypt against purchasing Russian Sukhoi Su-35, saying "We’ve made clear that if those systems were to be purchased, the CAATSA statute would require sanctions on the [al-Sisi's] regime."[37]

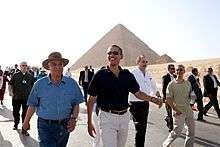

U.S. President Barack Obama tours the Pyramids during his famous Cairo speech about a "change" in the US relations with the Islamic world, June 2009.

U.S. President Barack Obama tours the Pyramids during his famous Cairo speech about a "change" in the US relations with the Islamic world, June 2009..jpg) U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry meets with Egypt's president Mohamed Morsi, who was the first Egyptian president to have gained power through an election, on May 25, 2013.

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry meets with Egypt's president Mohamed Morsi, who was the first Egyptian president to have gained power through an election, on May 25, 2013. Secretary Kerry talking with Egyptian Foreign Minister Nabil Fahmy of the interim government (which was installed in the aftermath of Morsi's overthrow until further elections could be held), on 3 November 2013.

Secretary Kerry talking with Egyptian Foreign Minister Nabil Fahmy of the interim government (which was installed in the aftermath of Morsi's overthrow until further elections could be held), on 3 November 2013. Secretary Kerry bids farewell to then-Egyptian Minister of Defense General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who was the Commander-in-Chief of the Egyptian Armed Forces.

Secretary Kerry bids farewell to then-Egyptian Minister of Defense General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, who was the Commander-in-Chief of the Egyptian Armed Forces.

References

- "Commentary: The U.S. is right to restore aid to Egypt". Reuters. July 30, 2018.

- Burns, William J. "Punishing Nasser." In Economic Aid and American Policy toward Egypt, 1955-1981. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1985.

- Craig A. Daigle, "The Russians are going: Sadat, Nixon and the Soviet presence in Egypt." Middle East 8.1 (2004): 1.

- Moshe Gat (2012). In Search of a Peace Settlement: Egypt and Israel Between the Wars, 1967-1973. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 256–58.

- Adfi Safty, "Sadat's Negotiations with the United States and Israel: From Sinai to Camp David," American Journal of Economics & Sociology, July 1991, 50#3 pp 285–298

- Mannin G. Weinbaum, "Egypt's 'Infitah' and the Politics of US Economic Assistance," Middle Eastern Studies, March 1985, Vol. 21 Issue 2, pp 206–222

- "Scenesetter: President Mubarak's visit to Washington". U.S. Department of State. 2009-05-19.

- "RANKED: The world's 9 strongest militaries". Business Insider. Retrieved 2017-06-26.

- "CNN.com - Mubarak warns of '100 bin Ladens' - Mar. 31, 2003". www.cnn.com. Retrieved 2017-06-26.

- O'Brien, Fiona (6 February 2003). "African Union summit opposed to war in Iraq". The World Revolution. Archived from the original on 7 January 2004. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- "BBC NEWS | Middle East | Arab states line up behind Iraq". news.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2017-06-26.

- Hall, Mimi; Richard Wolf (4 February 2011). "Transition could weaken U.S. anti-terror efforts". USA Today. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- Bengali, Shashank; Laura King (October 9, 2013). "U.S. to partially cut aid to Egypt". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- "Egypt unrest: NGO offices raided in Cairo". BBC News. 29 December 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- "US says Egypt agrees to stop raids on democracy groups". BBC News. 30 December 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- "Egypt PM dismisses US aid threat over activists' trial". BBC News. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- "US senators warn Egypt of 'disastrous' rupture in ties". BBC News. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- "Egypt judges in NGO funding trial resign". BBC News. 29 February 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- "Foreign NGO workers reach Cyprus after leaving Egypt". BBC News. 2 March 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- "Egypt 'lifts' travel ban on US NGO worker". BBC News. 1 March 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- "US and Egypt seek to repair relationship after NGO row". BBC News. 7 March 2012. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- Brian Walker; Paul Cruickshank; Tracy Doueiry (11 September 2012). "Protesters storm U.S. Embassy in Cairo". CNN. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- "Cairo protesters scale U.S. Embassy wall, remove flag". USA Today. 11 September 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- Jonathan Marcus (2012-09-13). "Obama: Egypt is not US ally, nor an enemy". BBC News. Retrieved 2016-10-01.

- "Obama: Egypt Not An Ally, But Not An Enemy". Huffington Post. 13 September 2012.

- "Obama: Egypt neither enemy nor ally". Reuters. 13 September 2012.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 2014-06-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Sharp, Jeremy M. (12 March 2019). "Egypt: Background and U.S. Relations" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- Holland, Steve; Mason, Jeff (15 August 2013). "Obama cancels military exercises, condemns violence in Egypt". Reuters. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- "Clouded U.S. policy on Egypt". Foreign Policy. 2013-02-26. Retrieved 2016-10-01.

- "The Weirdest Story in the History of the World". Talkingpointsmemo.com. 2013-07-08. Retrieved 2016-10-01.

- "US: We did not support particular Egyptian presidential candidate". Egypt Independent. 2012-07-16. Retrieved 2016-10-01.

- "Liberal and Christian figures, groups protest Clinton's Egypt visit". Al-Ahram Weekly. 15 July 2012. Retrieved 2016-10-01.

- "US unlocks military aid to Egypt, backing President Sisi". BBC News. 22 June 2014.

- Reuters. (February 10, 2017). "Analysis: Trump presidency heralds new era of US-Egypt ties". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- "Why US aid to Egypt is never under threat". Al-Jazeera. 3 October 2017.

- "Pompeo: Egypt would face sanctions over Russian Su-35s". Anadolu Agency. April 10, 2019.

Further reading

- Alterman, Jon B. (2002). Egypt and American Foreign Assistance, 1952–1958. New York, NY: Palgrave.

- Burns, William J. (1985). Economic Aid and American Policy Toward Egypt, 1955–1981. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

- Borzutzky, Silvia and David Berger. "Dammed If You Do, Dammed If You Don't: The Eisenhower Administration and the Aswan Dam," Middle East Journal, Winter 2010, 64#1 pp 84–102

- Cohen, Stephen P. Beyond America's grasp: a century of failed diplomacy in the Middle East (2009)

- Gardner, Lloyd C. The Road to Tahrir Square: Egypt and the United States from the Rise of Nasser to the Fall of Mubarak (2011)

- Mikhail, Mona. "Egyptian Americans." Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America, edited by Thomas Riggs, (3rd ed., vol. 2, Gale, 2014, pp. 61-71). online

- Oren, Michael B. Power, faith, and fantasy: America in the Middle East, 1776 to the present (2008)

- O'Sullivan, Christopher D. FDR and the End of Empire: The Origins of American Power in the Middle East (2012)

.svg.png)