American Convention on Human Rights

The American Convention on Human Rights, also known as the Pact of San José, is an international human rights instrument. It was adopted by many countries in the Western Hemisphere in San José, Costa Rica, on 22 November 1969. It came into force after the eleventh instrument of ratification (that of Grenada) was deposited on 18 July 1978.

Long name:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Signed | 22 November 1969 |

| Location | San José, Costa Rica |

| Effective | 18 July 1978 |

| Condition | 11 ratifications |

| Parties | 24 23 (from September 2013) |

| Depositary | General Secretariat of the Organization of American States |

The bodies responsible for overseeing compliance with the Convention are the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, both of which are organs of the Organization of American States (OAS).

Content and purpose

According to its preamble, the purpose of the Convention is "to consolidate in this hemisphere, within the framework of democratic institutions, a system of personal liberty and social justice based on respect for the essential rights of man."

Chapter I establishes the general obligation of the states parties to uphold the rights set forth in the Convention to all persons under their jurisdiction, and to adapt their domestic laws to bring them into line with the Convention. The 23 articles of Chapter II give a list of individual civil and political rights due to all persons, including the right to life "in general, from the moment of conception",[1] to humane treatment, to a fair trial, to privacy, to freedom of conscience, freedom of assembly, freedom of movement, etc. Article 15 prohibits "any propaganda for war and any advocacy of national, racial, or religious hatred that constitute incitement to lawless violence or to any other similar action against any person on any grounds including those of race, color, religion, language, or national origin" to be considered as offence punishable by law.[2] This provision is established under influence of Article 20 of the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights. The single article in Chapter III deals with economic, social, and cultural rights. The somewhat cursory treatment given to this issue here was expanded some ten years later with the Protocol of San Salvador (see below).

Chapter IV describes those circumstances in which certain rights can be temporarily suspended, such as during states of emergency, and the formalities to be followed for such suspension to be valid. However, it does not authorize any suspension of Article 3 (right to juridical personality), Article 4 (right to life), Article 5 (right to humane treatment), Article 6 (freedom from slavery), Article 9 (freedom from ex post facto laws), Article 12 (freedom of conscience and religion), Article 17 (right to family), Article 18 (right to the name), Article 19 (rights of the child), Article 20 (right to nationality), or Article 23 (right to participate in government).[3]

Chapter V, with a nod to the balance between rights and duties enshrined in the earlier American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man, points out that individuals have responsibilities as well as rights.

Chapters VI, VII, VIII, and IX contain provisions for the creation and operation of the two bodies responsible for overseeing compliance with the Convention: the Inter-American Commission, based in Washington, D.C., United States, and the Inter-American Court, headquartered in San José, Costa Rica.

Chapter X deals with mechanisms for ratifying the Convention, amending it or placing reservations in it, or denouncing it. Various transitory provisions are set forth in Chapter XI.'

Additional protocols

In the ensuing years, the states parties to the American Convention have supplemented its provisions with two additional protocols.

The first, the Additional Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights in the area of Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (more commonly known as the "Protocol of San Salvador"), was opened for signature in the city of San Salvador, El Salvador, on 17 November 1988. It represented an attempt to take the inter-American human rights system to a higher level by enshrining its protection of so-called second-generation rights in the economic, social, and cultural spheres. The protocol's provisions cover such areas as the right to work, the right to health, the right to food, and the right to education. It came into effect on 16 November 1999 and has been ratified by 16 nations (see below).[4]

The second, the Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights to Abolish the Death Penalty, was adopted at Asunción, Paraguay, on 8 June 1990. While Article 4 of the American Convention had already placed severe restrictions on the states' ability to impose the death penalty – only applicable for the most serious crimes; no reinstatement once abolished; not to be used for political offenses or common crimes; not to be used against those aged under 18 or over 70, or against pregnant women – signing this protocol formalizes a state's solemn commitment to refrain from using capital punishment in any peacetime circumstance. To date it has been ratified by 13 nations (see below).[5]

Inter-American Court's Interpretation

The Inter-American Court makes a broad interpretation of the American Convention. It interprets it according to the pro hominem principle, in an evolutive fashion and making use of other treaties and soft law. The result is that, in practice, the Inter-American Court modifies the content of the American Convention.[6]

Ratifications

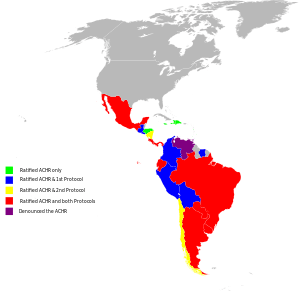

As of 2013, 25 of the 35 OAS's member states have ratified the Convention, while two have denounced it subsequently, leaving 23 active parties:[7]

| Country | Ratification date | 1st additional protocol | Additional Protocol on the Death Penalty | Denunciation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 14 August 1984 | 30 June 2003 | 18 June 2008 | |

| Barbados | 5 December 1981 | |||

| Bolivia | 20 June 1979 | 12 July 2006 | ||

| Brazil | 9 July 1992 | 8 August 1996 | 31 July 1996 | |

| Chile | 8 August 1990 | 4 August 2008 | ||

| Colombia | 28 May 1973 | 10 October 1997 | ||

| Costa Rica | 2 March 1970 | 9 September 1999 | 30 March 1998 | |

| Dominica | 3 June 1993 | |||

| Dominican Republic | 21 January 1978 | 27 January 2011 | ||

| Ecuador | 8 December 1997 | 2 February 1993 | 5 February 1998 | |

| El Salvador | 20 June 1978 | 4 May 1995 | ||

| Grenada | 14 July 1978 | |||

| Guatemala | 27 April 1978 | 30 May 2000 | ||

| Haiti | 14 September 1977 | |||

| Honduras | 5 September 1977 | 14 September 2011 | 10 November 2011 | |

| Jamaica | 19 July 1978 | |||

| Mexico | 2 March 1981 | 8 March 1996 | 28 June 2007 | |

| Nicaragua | 25 September 1979 | 15 December 2009 | 24 March 1999 | |

| Panama | 8 May 1978 | 28 October 1992 | 27 June 1991 | |

| Paraguay | 18 August 1989 | 28 May 1997 | 31 October 2000 | |

| Peru | 12 July 1978 | 17 May 1995 | ||

| Suriname | 12 December 1987 | 28 February 1990 | ||

| Trinidad and Tobago | 4 April 1991 | 26 May 1998 | ||

| Uruguay | 26 March 1985 | 21 December 1995 | 8 February 1994 | |

| Venezuela | 23 June 1977 | 24 August 1992 | 10 September 2012 |

Trinidad and Tobago denounced the Convention on 26 May 1998 (effective 26 May 1999) over the death penalty issue.[8] Venezuela denounced the Convention on 10 September 2012 accusing the Inter-American Court and Commission to undermine its Government's stability by interfering with its domestic affairs. Necessary reforms of the institution were blocked. Therefore, it would henceforth increase its cooperation with the United Nations Human Rights Council.[9] Denunciations, according to Article 78 of the ACHR, become effective one year after having been declared. They do not release the state party from its obligations resulting from acts that have occurred before the effective date of denunciation.

The treaty is open to all OAS member states, although to date it has not been ratified by Canada or several of the English-speaking Caribbean nations; the United States signed it in 1977 but has not proceeded with ratification.

Canada did at one point seriously consider ratification, but has decided against it, despite being in principle in favour of such a treaty. The ACHR, having been largely drafted by the predominantly Roman Catholic nations of Latin America, contains anti-abortion provisions, specifically, Article 4.1:

Every person has the right to have his life respected. This right shall be protected by law and, in general, from the moment of conception. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his life.[10]

This conflicts with the current legality of abortions in Canada. Although Canada could ratify the convention with a reservation with respect to abortion (as did Mexico[11]), that would contradict Canada's stated opposition to the making of reservations to human rights treaties. Another solution would be for the other states to remove the anti-abortion provisions, but that is unlikely to occur due to strong opposition to abortion in those countries.

See also

Notes

- Article 4(1). To understand the breadth of this statement see Controversial Conceptions: The Unborn in the American Convention on Human Rights

- Article 13(5)

- Article 27(2)

- ":: Multilateral Treaties > Department of International Law > OAS ::". www.oas.org. Retrieved 2019-06-27.

- ":: Multilateral Treaties > Department of International Law > OAS ::". www.oas.org. Retrieved 2019-06-27.

- To understand the breadth of this statement see The American Convention on Human Rights: Updated by the Inter-American Court

- "American Convention on Human Rights "Pact of San Jose, Costa Rica" - Signatories and Ratifications". www.oas.org.

- "Notice to Denounce the American Convention on Human Rights". Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- "Letter to the OAS Secretary General" (PDF). Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- To understand the breadth of this statement see Controversial Conceptions: The Unborn in the American Convention on Human Rights

- "Basic Documents - Ratifications of the Convention". www.cidh.org. Retrieved 2019-06-27.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- American Convention on Human Rights (text)

- Inter-American Commission on Human Rights

- Inter-American Court of Human Rights