Jacobo Árbenz

Juan Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán (Spanish pronunciation: [xuan xaˈkoβo ˈaɾβenz ɣuzˈman]; September 14, 1913 – January 27, 1971) was a Guatemalan military officer and politician who served as the 25th President of Guatemala. He was Minister of National Defense from 1944 to 1951, and the second democratically elected President of Guatemala from 1951 to 1954. He was a major figure in the ten-year Guatemalan Revolution, which represented some of the few years of representative democracy in Guatemalan history. The landmark program of agrarian reform Árbenz enacted as president was very influential across Latin America.[1]

Jacobo Árbenz | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| 25th President of Guatemala | |

| In office March 15, 1951 – June 27, 1954 | |

| Preceded by | Juan José Arévalo |

| Succeeded by | Carlos Enrique Díaz de León |

| 1st Minister of National Defence of Guatemala | |

| In office March 15, 1945 – March 15, 1951 | |

| President | Juan José Arévalo |

| Chief | Francisco Javier Arana Carlos Paz Tejada |

| Preceded by | Position established Francisco Javier Arana (as Secretary of Defence) |

| Succeeded by | José Ángel Sánchez |

| Head of State and Government of Guatemala | |

| In office October 20, 1944 – March 15, 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Federico Ponce Vaides |

| Succeeded by | Juan José Arévalo |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán September 14, 1913 Quetzaltenango, Guatemala |

| Died | January 27, 1971 (aged 57) Mexico City, Mexico |

| Political party | Revolutionary Action Party |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | 3, including Arabella |

| Alma mater | Politecnic School |

| Profession | Soldier |

| Signature |  |

| Website | Official website (tribute) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Guatemalan Army |

| Years of service | 1932–1954 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Unit | Guardia de Honor |

| Battles/wars | Guatemalan Revolution 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état |

Árbenz was born in 1913 to a wealthy family, son of a Swiss German father and a Guatemalan mother. He graduated with high honors from a military academy in 1935, and served in the army until 1944, quickly rising through the ranks. During this period, he witnessed the violent repression of agrarian laborers by the United States-backed dictator Jorge Ubico, and was personally required to escort chain-gangs of prisoners, an experience that contributed to his progressive views. In 1938 he met and married María Vilanova, who was a great ideological influence on him, as was José Manuel Fortuny, a Guatemalan communist. In October 1944 several civilian groups and progressive military factions led by Árbenz and Francisco Arana rebelled against Ubico's repressive policies. In the elections that followed, Juan José Arévalo was elected president, and began a highly popular program of social reform. Árbenz was appointed Minister of Defense, and played a crucial role in putting down a military coup in 1949.[2][3][4][5]

After the death of Arana, Árbenz contested the presidential elections that were held in 1950 and without significant opposition defeated Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, his nearest challenger, by a margin of over 50%. He took office on March 15, 1951, and continued the social reform policies of his predecessor. These reforms included an expanded right to vote, the ability of workers to organize, legitimizing political parties, and allowing public debate.[6] The centerpiece of his policy was an agrarian reform law under which uncultivated portions of large land-holdings were expropriated in return for compensation and redistributed to poverty-stricken agricultural laborers. Approximately 500,000 people benefited from the decree. The majority of them were indigenous people, whose forebears had been dispossessed after the Spanish invasion.

His policies ran afoul of the United Fruit Company, which lobbied the United States government to have him overthrown. The US was also concerned by the presence of communists in the Guatemalan government, and Árbenz was ousted in the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état engineered by the US Department of State and the Central Intelligence Agency. Colonel Carlos Castillo Armas replaced him as president. Árbenz went into exile through several countries, where his family gradually fell apart. His daughter committed suicide, and he descended into alcoholism, eventually dying in Mexico in 1971. In October 2011, the Guatemalan government issued an apology for Árbenz's overthrow.

Early life

Árbenz was born in Quetzaltenango, the second-largest city in Guatemala, in 1913. He was the son of a Swiss German pharmacist, Hans Jakob Arbenz Gröbli,[7][8] who immigrated to Guatemala in 1901. His mother, Octavia Guzmán Caballeros, was a Ladino woman from a middle-class family who worked as a primary school teacher.[8] His family was relatively wealthy and upper-class; his childhood has been described as "comfortable".[9] At some point during his childhood, his father became addicted to morphine and began to neglect the family business. He eventually went bankrupt, forcing the family to move to a rural estate that a wealthy friend had set aside for them "out of charity". Jacobo had originally desired to be an economist or an engineer, but since the family was now impoverished, he could not afford to go to a university. He initially did not want to join the military, but there was a scholarship available through the Escuela Politécnica for military cadets. He applied, passed all of the entrance exams, and entered as a cadet in 1932. His father committed suicide two years after Árbenz entered the academy.[9]

Military career and marriage

Árbenz excelled in the academy, and was deemed "an exceptional student". He became "first sergeant", the highest honor bestowed upon cadets; only six people received the honor from 1924 to 1944. His abilities earned him an unusual level of respect among the officers at the school, including Major John Considine, the US director of the school, and of other US officers who served at the school. A fellow officer later said that "his abilities were such that the officers treated him with a respect that was rarely granted to a cadet."[9] Árbenz graduated in 1935.[9]

After graduating, he served a stint as a junior officer at Fort San José in Guatemala City and later another under "an illiterate Colonel" in a small garrison in the village of San Juan Sacatepéquez. While at San José, Árbenz had to lead squads of soldiers who were escorting chain gangs of prisoners (including political prisoners) to perform forced labor. The experience traumatized Árbenz, who said he felt like a capataz (i.e., a "foreman").[9] During this period he first met Francisco Arana.[9]

Árbenz was asked to fill a vacant teaching position at the academy in 1937. Árbenz taught a wide range of subjects, including military matters, history, and physics. He was promoted to captain six years later, and placed in charge of the entire corps of cadets. His position was the third highest in the academy and was considered one of the most prestigious positions a young officer could hold.[9]

In 1938 he met his future wife María Vilanova, the daughter of a wealthy Salvadoran landowner and a Guatemalan mother from a wealthy family. They were married a few months later, without the approval of María's parents, who felt she should not marry an army lieutenant who was not wealthy.[9] María was 24 at the time of the wedding, and Jacobo was 26. María later wrote that, while the two were very different in many ways, their desire for political change drew them together. Árbenz stated that his wife had a great influence on him.[9] It was through her that Árbenz was exposed to Marxism. María had received a copy of The Communist Manifesto at a women's congress and left a copy of it on Jacobo's bedside table when she left for a vacation. Jacobo was "moved" by the Manifesto, and he and María discussed it with each other. Both felt that it explained many things they had been feeling. Afterwards, Jacobo began reading more works by Marx, Lenin, and Stalin and by the late 1940s was regularly interacting with a group of Guatemalan communists.[10]

October revolution and defense ministership

Historical background

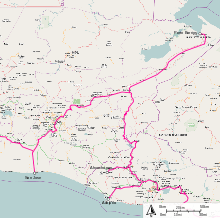

In 1871 the government of Justo Rufino Barrios passed laws confiscating the lands of the native Mayan people and compelling them to work in coffee plantations for minimal compensation.[2] Several United States-based companies, including the United Fruit Company, received this public land, and were exempted from paying taxes.[11][12] In 1929 the Great Depression led to the collapse of the economy and a rise in unemployment, leading to unrest among workers and laborers. Fearing the possibility of a revolution, the landed elite lent their support to Jorge Ubico, who won the election that followed in 1931, an election in which he was the only candidate.[13][12] With the support of the United States, Ubico soon became one of Latin America's most brutal dictators.[14] Ubico abolished the system of debt peonage introduced by Barrios and replaced it with a vagrancy law, which required all men of working age who did not own land to perform a minimum of 100 days of hard labor.[15][2] In addition, the state made use of unpaid Indian labor to work on public infrastructure such as roads and railroads. Ubico also froze wages at very low levels, and passed a law allowing landowners complete immunity from prosecution for any action they took to defend their property,[15] including allowing them to execute workers as a "disciplinary" measure.[16][17][18][19] The result of these laws was a tremendous resentment against him among agricultural laborers.[20] Ubico was highly contemptuous of the country's indigenous people, once stating that they resembled donkeys.[21] He gave away 200,000 hectares (490,000 acres) hectares of public land to the United Fruit Company, and allowed the US military to establish bases in Guatemala.[16][17][18][19][22][23]

October revolution

In May 1944 a series of protests against Ubico broke out at the university in Guatemala City. Ubico responded by suspending the constitution on June 22, 1944.[24][25][26] The protests, which by this point included many middle-class members and junior army officers in addition to students and workers, gained momentum, eventually forcing Ubico's resignation at the end of June.[27][16][28] Ubico appointed a three-person junta led by General Federico Ponce Vaides to succeed him. Although Ponce Vaides initially promised to hold free elections, when the congress met on July 3, soldiers held everyone at gunpoint and forced them to appoint Ponce Vaides interim president.[28] The repressive policies of the Ubico administration were continued.[16][28] Opposition groups began organizing again, this time joined by many prominent political and military leaders, who deemed the Ponce regime unconstitutional. Árbenz had been one of the few officers in the military to protest the actions of Ponce Vaides.[29] Ubico had fired Árbenz from his teaching post at the Escuela Politécnica, and since then Árbenz had been living in El Salvador, organizing a band of revolutionary exiles.[30] Árbenz was one of the leaders of the plot within the army, along with Major Aldana Sandoval. Árbenz insisted that civilians also be included in the coup, over the protests of the other military men involved. Sandoval later said that all contact with the civilians during the coup was through Árbenz.[29]

On October 19, 1944, a small group of soldiers and students led by Árbenz and Francisco Javier Arana attacked the National Palace in what later became known as the "October Revolution".[30] Arana had not initially been a party to the coup, but his position of authority within the army meant that he was key to its success.[31] They were joined the next day by other factions of the army and the civilian population. Initially, the battle went against the revolutionaries, but after an appeal for support their ranks were swelled by unionists and students, and they eventually subdued the police and army factions loyal to Ponce Vaides. On October 20, the next day, Ponce Vaides surrendered unconditionally.[32] Árbenz and Arana both fought with distinction during the revolt,[31] and despite the idealistic rhetoric of the revolution, both were also offered material rewards: Árbenz was promoted from captain to lieutenant colonel, and Arana from major to full colonel.[33] The junta promised free and open elections to the presidency and the congress, as well as for a constituent assembly.[34] The resignation of Ponce Vaides and the creation of the junta has been considered by scholars to be the beginning of the Guatemalan Revolution.[34] However, the revolutionary junta did not immediately threaten the interests of the landed elite. Two days after Ponce Vaides' resignation, a violent protest erupted at Patzicía, a small Indian hamlet. The junta responded with swift brutality, silencing the protest. The dead civilians included women and children.[35]

Elections subsequently took place in December 1944. Although only literate men were allowed to vote, the elections were broadly considered free and fair.[36][37][38] Unlike in similar historical situations, none of the junta members stood for election.[36] The winner of the 1944 elections was a teacher named Juan José Arévalo, who ran under a coalition of leftist parties known as the "Partido Acción Revolucionaria'" ("Revolutionary Action Party", PAR), and won 85% of the vote.[37] Arana did not wish to turn over power to a civilian administration.[31] He initially tried to persuade Árbenz and Toriello to postpone the election, and after Arévalo was elected, he asked them to declare the results invalid.[31] Árbenz and Toriello insisted that Arévalo be allowed to take power, which Arana reluctantly agreed to, on the condition that Arana's position as the commander of the military be unchallenged. Arévalo had no choice but to agree to this, and so the new Guatemalan constitution, adopted in 1945, created a new position of "Commander of the Armed Forces", a position that was more powerful than that of the defense minister. He could only be removed by Congress, and even then only if he was found to have broken the law.[39] When Arévalo was inaugurated as president, Arana stepped into this new position, and Árbenz was sworn in as defense minister.[31]

Government of Juan José Arévalo

Arévalo described his ideology as "spiritual socialism". He was anti-communism and believed in a capitalist society regulated to ensure that its benefits went to the entire population.[40] Arévalo's ideology was reflected in the new constitution that was ratified by the Guatemalan assembly soon after his inauguration, which was one of the most progressive in Latin America. It mandated suffrage for all but illiterate women, a decentralization of power, and provisions for a multiparty system. Communist parties were forbidden.[40] Once in office, Arévalo implemented these and other reforms, including minimum wage laws, increased educational funding, and labor reforms. The benefits of these reforms were largely restricted to the upper-middle classes and did little for the peasant agricultural laborers who made up the majority of the population.[41][42] Although his reforms were based on liberalism and capitalism, he was viewed with suspicion by the United States government, which would later portray him as a communist.[41][42]

When Árbenz was sworn in as defense minister under President Arévalo, he became the first to hold the portfolio, since it had previously been known as the Ministry of War. In the fall of 1947, Árbenz, as defense minister, objected to the deportation of several workers after they had been accused of being communists. Well-known communist José Manuel Fortuny was intrigued by this action and decided to visit him, and found Árbenz to be different from the stereotypical Central American military officer. That first meeting was followed by others until Árbenz invited Fortuny to his house for discussions that usually extended for hours. Like Árbenz, Fortuny was inspired by a fierce nationalism and a burning desire to improve the conditions of the Guatemalan people, and, like Árbenz, he sought answers in Marxist theory. This relationship would strongly influence Árbenz in the future.[43]

On December 16, 1945, Arévalo was incapacitated for a while after a car accident.[44] The leaders of the Revolutionary Action Party (PAR), which was the party that supported the government, were afraid that Arana would take the opportunity to launch a coup and so struck a deal with him, which later came to be known as the Pacto del Barranco (Pact of the Ravine).[44] Under the terms of this pact, Arana agreed to refrain from seizing power with the military; in return, the PAR agreed to support Arana's candidacy in the next presidential election, scheduled for November 1950.[44] Arévalo himself recovered swiftly, but was forced to support the agreement.[44] However, by 1949 the National Renovation Party and the PAR were both openly hostile to Arana due to his lack of support for labor rights. The leftist parties decided to back Árbenz instead, as they believed that only a military officer could defeat Arana.[45] In 1947 Arana had demanded that certain labor leaders be expelled from the country; Árbenz vocally disagreed with Arana, and the former's intervention limited the number of deportees.[45]

The land reforms brought about by the Arévalo administration threatened the interests of the landed elite, who sought a candidate who would be more amenable to their terms. They began to prop up Arana as a figure of resistance to Arévalo's reforms.[46] The summer of 1949 saw intense political conflict in the councils of the Guatemalan military between supporters of Arana and those of Árbenz, over the choice of Arana's successor.[lower-alpha 1] On July 16, 1949, Arana delivered an ultimatum to Arévalo, demanding the expulsion of all of Árbenz's supporters from the cabinet and the military; he threatened a coup if his demands were not met. Arévalo informed Árbenz and other progressive leaders of the ultimatum; all agreed that Arana should be exiled.[47] Two days later, Arévalo and Arana had another meeting; on the way back, Arana's convoy was intercepted by a small force led by Árbenz. A shootout ensued, killing three men, including Arana. Historian Piero Gleijeses stated that Árbenz probably had orders to capture, rather than to kill, Arana.[47] Arana's supporters in the military rose up in revolt, but they were leaderless, and by the next day the rebels asked for negotiations. The coup attempt left approximately 150 dead and 200 wounded.[47] Árbenz and a few other ministers suggested that the entire truth be made public; however, they were overruled by the majority of the cabinet, and Arévalo made a speech suggesting that Arana had been killed for refusing to lead a coup against the government.[47] Árbenz kept his silence over the death of Arana until 1968, refusing to speak out without first obtaining Arévalo's consent. He tried to persuade Arévalo to tell the entire story when the two met in Montevideo in the 1950s, during their exile: however, Arévalo was unwilling, and Árbenz did not press his case.[48]

1950 election

Árbenz's role as defense minister had already made him a strong candidate for the presidency, and his firm support of the government during the 1949 uprising further increased his prestige.[49] In 1950 the economically moderate Partido de Integridad Nacional (PIN) announced that Árbenz would be its presidential candidate in the upcoming election. The announcement was quickly followed by endorsements from most parties on the left, including the influential PAR, as well as from labor unions.[49] Árbenz carefully chose the PIN as the party to nominate him. Based on the advice of his friends and colleagues, he believed it would make his candidacy appear more moderate.[49] Árbenz himself resigned his position as Defense Minister on February 20 and declared his candidacy for the presidency. Arévalo wrote him an enthusiastic personal letter in response but publicly only reluctantly endorsed him, preferring, it is thought, his friend Víctor Manuel Giordani, who was then Health Minister. It was only the support Árbenz had, and the impossibility of Giordani being elected, that led to Arévalo deciding to support Árbenz.[50]

Prior to his death, Arana had planned to run in the 1950 presidential elections. His death left Árbenz without any serious opposition in the elections (leading some, including the CIA and US military intelligence, to speculate that Árbenz personally had him eliminated for this reason).[51] Árbenz had only a couple of significant challengers in the election, in a field of ten candidates.[49] One of these was Jorge García Granados, supported by some members of the upper-middle class who felt the revolution had gone too far. Another was Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, who had been a general under Ubico and had the support of the hardline opponents of the revolution. During his campaign, Árbenz promised to continue and expand the reforms begun under Arévalo.[52] Árbenz was expected to win the election comfortably because he had the support of both major political parties of the country, as well as that of the labor unions, which campaigned heavily on his behalf.[53] In addition to political support, Árbenz had great personal appeal. He was described as having "an engaging personality and a vibrant voice".[54] Árbenz's wife María also campaigned with him; despite her wealthy upbringing she had made an effort to speak for the interests of the Mayan peasantry and had become a national figure in her own right. Árbenz's two daughters also occasionally made public appearances with him.[55]

The election was held on November 15, 1950, with Árbenz winning more than 60% of the vote, in elections that were largely free and fair with the exception of the disenfranchisement of illiterate female voters.[49] Árbenz got more than three times as many votes as the runner-up, Ydígoras Fuentes. Fuentes claimed electoral fraud had benefited Árbenz, but scholars have pointed out that while fraud may possibly have given Árbenz some of his votes, it was not the reason that he won the election.[56] Árbenz's promise of land reform played a large role in ensuring his victory.[57] The election of Árbenz alarmed US State Department officials, who stated that Arana "has always represented the only positive conservative element in the Arévalo administration" and that his death would "strengthen Leftist [sic] materially", and that "developments forecast sharp leftist trend within the government."[58] Árbenz was inaugurated as president on March 15, 1951.[49]

Presidency

Inauguration and ideology

In his inaugural address, Árbenz promised to convert Guatemala from "a backward country with a predominantly feudal economy into a modern capitalist state".[59] He declared that he intended to reduce dependency on foreign markets and dampen the influence of foreign corporations over Guatemalan politics.[60] He said that he would modernize Guatemala's infrastructure without the aid of foreign capital.[61] Based on advice from the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, he set out to build more houses, ports, and roads.[59] Árbenz also set out to reform Guatemala's economic institutions; he planned to construct factories, increase mining, expand transportation infrastructure, and expand the banking system.[62] Land reform was the centerpiece of Árbenz's election campaign.[63][64] The revolutionary organizations that had helped put Árbenz in power kept constant pressure on him to live up to his campaign promises regarding land reform.[65] Agrarian reform was one of the areas of policy which the Arévalo administration had not ventured into;[62] when Árbenz took office, only 2% of the population owned 70% of the land.[66]

Historian Jim Handy described Árbenz's economic and political ideals as "decidedly pragmatic and capitalist in temper".[67] According to historian Stephen Schlesinger, while Árbenz did have a few communists in lower-level positions in his administration, he "was not a dictator, he was not a crypto-communist". Schlesinger described him as a democratic socialist.[68] Nevertheless, some of his policies, particularly those involving agrarian reform, would be branded as "communist" by the Guatemalan upper class and the United Fruit Company.[69][70] Historian Piero Gleijeses has argued that although Árbenz's policies were intentionally capitalist in nature, his personal views gradually shifted towards communism.[71][72] His goal was to increase Guatemala's economic and political independence, and he believed that to do this Guatemala needed to build a strong domestic economy.[73] He made an effort to reach out to the indigenous Mayan people, and sent government representatives to confer with them. From this effort he learned that the Maya held strongly to their ideals of dignity and self-determination; inspired in part by this, he stated in 1951 that "If the independence and prosperity of our people were incompatible, which for certain they are not, I am sure that the great majority of Guatemalans would prefer to be a poor nation, but free, and not a rich colony, but enslaved."[74]

Although the policies of the Árbenz government were based on a moderate form of capitalism,[75] the communist movement did grow stronger during his presidency, partly because Arévalo released its imprisoned leaders in 1944, and also through the strength of its teachers' union.[76] Although the Communist party was banned for much of the Guatemalan Revolution,[49] the Guatemalan government welcomed large numbers of communist and socialist refugees fleeing the dictatorial governments of neighboring countries, and this influx strengthened the domestic movement.[76] In addition, Árbenz had personal ties to some members of the communist Guatemalan Party of Labour, which was legalized during his government.[49] The most prominent of these was José Manuel Fortuny. Fortuny played the role of friend and adviser to Árbenz through the three years of his government, from 1951 to 1954.[77] Fortuny wrote several speeches for Árbenz, and in his role as agricultural secretary[78] helped craft the landmark agrarian reform bill. Despite his position in Árbenz's government, however, Fortuny never became a popular figure in Guatemala, and did not have a large popular following like some other communist leaders.[79] The communist party remained numerically weak, without any representation in Árbenz's cabinet of ministers.[79] A handful of communists were appointed to lower-level positions in the government.[68] Árbenz read and admired the works of Marx, Lenin, and Stalin (before Khrushchev's report); officials in his government eulogized Stalin as a "great statesman and leader ... whose passing is mourned by all progressive men".[80] The Guatemalan Congress paid tribute to Joseph Stalin with a "minute of silence" when Stalin died in 1953, a fact that was remarked upon by later observers.[81] Árbenz had several supporters among the communist members of the legislature, but they were only a small part of the government coalition.[68] Árbenz himself slowly moved towards communism as a part of his personal ideology, but did not join the communist party until 1957, three years after his overthrow, after he had been further radicalized by the actions of the CIA.[82]

Land reform

The biggest component of Árbenz's project of modernization was his agrarian reform bill.[83] Árbenz drafted the bill himself with the help of advisers that included some leaders of the communist party as well as non-communist economists.[84] He also sought advice from numerous economists from across Latin America.[83] The bill was passed by the National Assembly on June 17, 1952, and the program went into effect immediately. It transferred uncultivated land from large landowners to their poverty-stricken laborers, who would then be able to begin a viable farm of their own.[83] Árbenz was also motivated to pass the bill because he needed to generate capital for his public infrastructure projects within the country. At the behest of the United States, the World Bank had refused to grant Guatemala a loan in 1951, which made the shortage of capital more acute.[85]

The official title of the agrarian reform bill was Decree 900. It expropriated all uncultivated land from landholdings that were larger than 673 acres (272 ha). If the estates were between 672 acres (272 ha) and 224 acres (91 ha) in size, uncultivated land was expropriated only if less than two-thirds of it was in use.[85] The owners were compensated with government bonds, the value of which was equal to that of the land expropriated. The value of the land itself was the value that the owners had declared in their tax returns in 1952.[85] The redistribution was organized by local committees that included representatives from the landowners, the laborers, and the government.[85] Of the nearly 350,000 private land-holdings, only 1,710 were affected by expropriation. The law itself was cast in a moderate capitalist framework; however, it was implemented with great speed, which resulted in occasional arbitrary land seizures. There was also some violence, directed at landowners as well as at peasants who had minor landholdings of their own.[85] Árbenz himself, a landowner through his wife, gave up 1,700 acres (7 km2) of his own land in the land reform program.[86]

By June 1954, 1.4 million acres of land had been expropriated and distributed. Approximately 500,000 individuals, or one-sixth of the population, had received land by this point.[85] The decree also included provision of financial credit to the people who received the land. The National Agrarian Bank (Banco Nacional Agrario, or BNA) was created on July 7, 1953, and by June 1951 it had disbursed more than $9 million in small loans. 53,829 applicants received an average of 225 US dollars, which was twice as much as the Guatemalan per capita income.[85] The BNA developed a reputation for being a highly efficient government bureaucracy, and the United States government, Árbenz's biggest detractor, did not have anything negative to say about it.[85] The loans had a high repayment rate, and of the $3,371,185 handed out between March and November 1953, $3,049,092 had been repaid by June 1954.[85] The law also included provisions for nationalization of roads that passed through redistributed land, which greatly increased the connectivity of rural communities.[85]

Contrary to the predictions made by detractors of the government, the law resulted in a slight increase in Guatemalan agricultural productivity, and to an increase in cultivated area. Purchases of farm machinery also increased.[85] Overall, the law resulted in a significant improvement in living standards for many thousands of peasant families, the majority of whom were indigenous people. [85] Gleijeses stated that the injustices corrected by the law were far greater than the injustice of the relatively few arbitrary land seizures.[85] Historian Greg Grandin stated that the law was flawed in many respects; among other things, it was too cautious and deferential to the planters, and it created communal divisions among peasants. Nonetheless, it represented a fundamental power shift in favor of those that had been marginalized before then.[87] In 1953 the reform was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, but the Guatemalan Congress later impeached four judges associated with the ruling.[88]

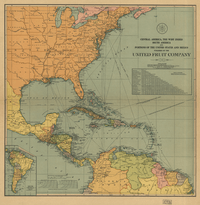

Relationship with the United Fruit Company

The relationship between Árbenz and the United Fruit Company has been described by historians as a "critical turning point in US dominance in the hemisphere".[89] The United Fruit Company, formed in 1899,[90] had major holdings of land and railroads across Central America, which it used to support its business of exporting bananas.[91] By 1930, it had been the largest landowner and employer in Guatemala for several years.[92] In return for the company's support, Ubico signed a contract with it that included a 99-year lease to massive tracts of land, and exemptions from virtually all taxes.[93] Ubico asked the company to pay its workers only 50 cents a day, to prevent other workers from demanding higher wages.[92] The company also virtually owned Puerto Barrios, Guatemala's only port to the Atlantic Ocean.[92] By 1950, the company's annual profits were 65 million US dollars, twice the revenue of the Guatemalan government.[94]

As a result, the company was seen as an impediment to progress by the revolutionary movement after 1944.[94][95] Thanks to its position as the country's largest landowner and employer, the reforms of Arévalo's government affected the UFC more than other companies, which led to a perception by the company that it was being specifically targeted by the reforms.[96] The company's labor troubles were compounded in 1952 when Árbenz passed Decree 900, the agrarian reform law. Of the 550,000 acres (220,000 ha) that the company owned, 15% were being cultivated; the rest of the land, which was idle, came under the scope of the agrarian reform law.[96] Additionally, Árbenz supported a strike of UFC workers in 1951, which eventually compelled the company to rehire a number of laid-off workers.[97]

The United Fruit Company responded with an intensive lobbying campaign against Árbenz in the United States.[98] The Guatemalan government reacted by saying that the company was the main obstacle to progress in the country. American historians observed that "to the Guatemalans it appeared that their country was being mercilessly exploited by foreign interests which took huge profits without making any contributions to the nation's welfare."[98] In 1953 200,000 acres (81,000 ha) of uncultivated land was expropriated under Árbenz's agrarian reform law, and the company was offered compensation at the rate of 2.99 US dollars to the acre, twice what it had paid when buying the property.[98] This resulted in further lobbying in Washington, particularly through Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, who had close ties to the company.[98] The company had begun a public relations campaign to discredit the Guatemalan government; overall, the company spent over a half-million dollars to influence both lawmakers and members of the public in the US that the Guatemalan government of Jacobo Árbenz needed to be overthrown.[99]

Coup d'état

Political motives

Several factors besides the lobbying campaign of the United Fruit Company led the United States to launch the coup that toppled Árbenz in 1954. The US government had grown more suspicious of the Guatemalan Revolution as the Cold War developed and the Guatemalan government clashed with US corporations on an increasing number of issues.[100] The US was also concerned that it had been infiltrated by communists[101] although historian Richard H. Immerman argued that during the early part of the Cold War, the US and the CIA were predisposed to see the revolutionary government as communist, despite Arévalo's ban of the communist party during his 1945–1951 presidency.[100] Additionally, the US government was concerned that the success of Árbenz's reforms would inspire similar movements elsewhere.[102] Until the end of its term, the Truman administration relied on purely diplomatic and economic means to attempt to reduce communist influences.[103]

Árbenz's enactment of Decree 900 in 1952 provoked Truman to authorize Operation PBFortune, a covert operation to overthrow Árbenz.[104] The plan had originally been suggested by the US-backed dictator of Nicaragua, Anastasio Somoza García, who said that if he were given weapons, he could overthrow the Guatemalan government.[104] The operation was to be led by Carlos Castillo Armas.[105] However, the US state department discovered the conspiracy, and secretary of state Dean Acheson persuaded Truman to abort the plan.[104][105] After being elected president of the US in November 1952, Dwight Eisenhower was more willing than Truman to use military tactics to remove regimes he disliked.[106][107] Several figures in his administration, including Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and his brother and CIA director Allen Dulles, had close ties to the United Fruit Company.[108][109] John Foster Dulles had previously represented United Fruit Company as a lawyer, and his brother, then-CIA director Allen Dulles was on the company's board of directors. Thomas Dudley Cabot, a former CEO of United Fruit, held the position of director of International Security Affairs in the State Department.[110] Undersecretary of State Bedell Smith later became a director of the UFC, while the wife of the UFC public relations director was Eisenhower's personal assistant. These connections made the Eisenhower administration more willing to overthrow the Guatemalan government.[108][109]

Operation PBSuccess

The CIA operation to overthrow Jacobo Árbenz, code-named Operation PBSuccess, was authorized by Eisenhower in August 1953.[111] Carlos Castillo Armas, once Arana's lieutenant, who had been exiled following the failed coup in 1949, was chosen to lead the coup.[112] Castillo Armas recruited a force of approximately 150 mercenaries from among Guatemalan exiles and the populations of nearby countries.[113] In January 1954, information about these preparations were leaked to the Guatemalan government, which issued statements implicating a "Government of the North" in a plot to overthrow Árbenz. The US government denied the allegations, and the US media uniformly took the side of the government; both argued that Árbenz had succumbed to communist propaganda.[114] The US stopped selling arms to Guatemala in 1951, and soon after blocked arms purchases from Canada, Germany, and Rhodesia.[115] By 1954, Árbenz had become desperate for weapons, and decided to acquire them secretly from Czechoslovakia, an action seen as establishing a communist beachhead in the Americas.[116][117] The shipment of these weapons was portrayed by the CIA as Soviet interference in the United States' backyard, and acted as the final spur for the CIA to launch its coup.[117]

Árbenz had intended the shipment of weapons from the Alfhem to be used to bolster peasant militia, in the event of army disloyalty, but the US informed the Guatemalan army chiefs of the shipment, forcing Árbenz to hand them over to the military, and deepening the rift between him and the chiefs of his army.[118] Castillo Armas' forces invaded Guatemala on June 18, 1954.[119] The invasion was accompanied by an intense campaign of psychological warfare presenting Castillo Armas' victory as a fait accompli, with the intent of forcing Árbenz to resign.[111][120] The most wide-reaching psychological weapon was the radio station known as the "Voice of Liberation", whose transmissions broadcast news of rebel troops converging on the capital, and contributed to massive demoralization among both the army and the civilian population.[121] Árbenz was confident that Castillo Armas could be defeated militarily,[122] but he worried that a defeat for Castillo Armas would provoke a US invasion.[122] Árbenz ordered Carlos Enrique Díaz, the chief of the army, to select officers to lead a counter-attack. Díaz chose a corps of officers who were all known to be men of personal integrity, and who were loyal to Árbenz.[122]

By June 21, Guatemalan soldiers had gathered at Zacapa under the command of Colonel Víctor M. León, who was believed to be loyal to Árbenz.[123] The leaders of the communist party also began to have their suspicions, and sent a member to investigate. He returned on June 25, reporting that the army was highly demoralized, and would not fight.[124][125] PGT Secretary General Alvarado Monzón informed Árbenz, who quickly sent another investigator of his own, who brought back a message asking Árbenz to resign. The officers believed that given US support for the rebels, defeat was inevitable, and Árbenz was to blame for it.[125] The message stated that if Árbenz did not resign, the army was likely to strike a deal with Castillo Armas.[125][124] On June 25, Árbenz announced that the army had abandoned the government, and that civilians needed to be armed in order to defend the country; however, only a few hundred individuals volunteered.[126][121] Seeing this, Díaz reneged on his support of the president, and began plotting to overthrow Árbenz with the assistance of other senior army officers. They informed US ambassador John Peurifoy of this plan, asking him to stop the hostilities in return for Árbenz's resignation.[127] Peurifoy promised to arrange a truce, and the plotters went to Árbenz and informed him of their decision. Árbenz, utterly exhausted and seeking to preserve at least a measure of the democratic reforms that he had brought, agreed. After informing his cabinet of his decision, he left the presidential palace at 8 pm on June 27, 1954, having taped a resignation speech that was broadcast an hour later.[127] In it, he stated that he was resigning in order to eliminate the "pretext for the invasion," and that he wished to preserve the gains of the October Revolution.[127] He walked to the nearby Mexican Embassy, seeking political asylum.[128]

Later life

Beginning of exile

After Árbenz's resignation, his family remained for 73 days at the Mexican embassy in Guatemala City, which was crowded with almost 300 exiles.[129] During this period, the CIA initiated a new set of operations against Árbenz, intended to discredit the former president and damage his reputation. The CIA obtained some of Árbenz's personal papers, and released parts of them after doctoring the documents. The CIA also promoted the notion that individuals in exile, such as Árbenz, should be prosecuted in Guatemala.[129] When they were finally allowed to leave the country, Árbenz was publicly humiliated at the airport when the authorities made the former president strip before the cameras,[130] claiming that he was carrying jewelry he had bought for his wife, María Cristina Vilanova, at Tiffany's in New York City, using funds from the presidency; no jewelry was found but the interrogation lasted for an hour.[131] Through this entire period, coverage of Árbenz in the Guatemalan press was very negative, influenced largely by the CIA's campaign.[130]

The family then initiated a long journey in exile that would take them first to Mexico, then to Canada, where they went to pick up Arabella (the Árbenzs' oldest daughter), and then to Switzerland via the Netherlands and Paris.[132] They hoped to obtain citizenship in Switzerland based on Árbenz's Swiss heritage. However, the former president did not wish to renounce his Guatemalan nationality, as he felt that such a gesture would have marked the end of his political career.[133] Árbenz and his family were the victims of a CIA-orchestrated and intense defamation campaign that lasted from 1954 to 1960.[134] A close friend of Árbenz, Carlos Manuel Pellecer, turned out to be a spy working for the CIA.[135]

Europe and Uruguay

After being unable to obtain citizenship in Switzerland, the Árbenz family moved to Paris, where the French government gave them permission to live for a year, on the condition that they did not participate in any political activity,[133] then to Prague, the capital of Czechoslovakia. After only three months, he moved to Moscow, which came as a relief to him from the harsh treatment he received in Czechoslovakia.[136] While traveling in the Soviet Union and its vassal states, he was constantly criticized in the press in Guatemala and the US, on the grounds that he was showing his true communist colors by going there.[136] After a brief stay in Moscow, Árbenz returned to Prague and then to Paris. From there he separated from his wife: María traveled to El Salvador to take care of family affairs.[136] The separation made life increasingly difficult for Árbenz, and he slipped into depression and took to drinking excessively.[136] He tried several times to return to Latin America, and was finally allowed in 1957 to move to Uruguay.[137] where he joined the Communist Party.[138] The CIA made several attempts to prevent Árbenz from receiving a Uruguayan visa, but these were unsuccessful, and the Uruguayan government allowed Árbenz to travel there as a political refugee.[139] Árbenz arrived in Montevideo on May 13, 1957, where he was met by a hostile "reception committee" organized by the CIA. However, he was still a figure of some note in leftist circles in the city, which partially explained the CIA's hostility.[140]

While Árbenz was living in Montevideo, his wife came to join him. He was also visited by Arévalo a year after his own arrival there. Although the relationship between Arévalo and the Árbenz family was initially friendly, it soon deteriorated due to differences between the two men.[141] Arévalo himself was not under surveillance in Uruguay and was occasionally able to express himself through articles in the popular press. He left for Venezuela a year after his arrival to take up a position as a teacher.[140] During his stay in Uruguay, Árbenz was initially required to report to the police on a daily basis; eventually, however, this requirement was relaxed somewhat to once every eight days.[140] María Árbenz later stated that the couple was pleased by the hospitality they received in Uruguay, and would have stayed there indefinitely had they received permission to do so.[140]

Daughter's suicide and death

After the Cuban Revolution of 1959, a representative of the Fidel Castro government asked Árbenz to come to Cuba, to which he readily agreed, sensing an opportunity to live with fewer restrictions on himself. He flew to Havana in July 1960, and, caught up in the spirit of the recent revolution, began to participate in public events.[142] His presence so close to Guatemala once again increased the negative coverage he received in the Guatemalan press. He was offered the leadership of some revolutionary movements in Guatemala but refused, as he was pessimistic about the outcome.[142]

In 1965 Árbenz participated in the Communist Congress in Helsinki.[142] Soon afterwards, his daughter Arabella committed suicide in Bogotá, an incident that badly affected Árbenz. Following her funeral, the Árbenz family remained indefinitely in Mexico City, while Árbenz himself spent some time in France and Switzerland, with the ultimate objective of settling down in Mexico.[142]

On one of his visits to Mexico, Árbenz contracted a serious illness, and by the end of 1970 he was very ill. He died soon after. Historians disagree as to the manner of his death: Roberto Garcia Ferreira stated that he died of a heart attack while taking a bath,[142] while historian Cindy Forster wrote that he committed suicide.[143] In October 1995, Árbenz's remains were eventually repatriated to Guatemala, accompanied by his widow María. The Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala awarded him with a posthumous decoration soon after.[142]

Guatemalan government apology

Following years of campaigning, the Arbenz Family took the Guatemalan Government to Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in Washington D.C. It accepted the complaint in 2006, leading to five years of stop-and-start negotiations.[144][145] In May 2011 the Guatemalan government signed an agreement with Árbenz's surviving family to restore his legacy and publicly apologize for the government's role in ousting him. This included a financial settlement to the family, as well as the family's insistence on social reparations and policies for the future of the Guatemalan people, a first for a judgement of this kind from the OAS. The formal apology was made at the National Palace by Guatemalan President Alvaro Colom on October 20, 2011, to Jacobo Árbenz Vilanova, the son of the former president, and a Guatemalan politician.[69] Colom stated, "It was a crime to Guatemalan society and it was an act of aggression to a government starting its democratic spring."[69] The agreement established several forms of reparation for the next of kin of Árbenz Guzmán. Among other measures, the state:[69][146]

- held a public ceremony recognizing its responsibility

- sent a letter of apology to the next of kin

- named a hall of the National Museum of History and the highway to the Atlantic after the former president

- revised the basic national school curriculum (Currículo Nacional Base)

- established a degree program in Human Rights, Pluriculturalism, and Reconciliation of Indigenous Peoples

- held a photographic exhibition on Árbenz Guzmán and his legacy at the National Museum of History

- recovered the wealth of photographs of the Árbenz Guzmán family

- published a book of photos

- reissued the book Mi esposo, el presidente Árbenz (My Husband President Árbenz)

- prepared and published a biography of the former President, and

- issued a series of postage stamps in his honor.

The official statement issued by the government recognized its responsibility for "failing to comply with its obligation to guarantee, respect, and protect the human rights of the victims to a fair trial, to property, to equal protection before the law, and to judicial protection, which are protected in the American Convention on Human Rights and which were violated against former President Juan Jacobo Árbenz Guzman, his wife, María Cristina Villanova, and his children, Juan Jacobo, María Leonora, and Arabella, all surnamed Árbenz Villanova."[146]

Legacy

Historian Roberto Garcia Ferreira wrote in 2008 that Árbenz's legacy was still a matter of great dispute in Guatemala itself, while arguing that the image of Árbenz was significantly shaped by the CIA media campaign that followed the 1954 coup.[147] Garcia Ferreira said that the revolutionary government represented one of the few periods in which "state authority was used to promote the interests of the nation's masses."[148] Forster described Árbenz's legacy in the following terms: "In 1952 the Agrarian Reform Law swept the land, destroying forever the hegemony of the planters. Árbenz in effect legislated a new social order ... The revolutionary decade ... plays a central role in twentieth-century Guatemalan history because it was more comprehensive than any period of reform before or since."[149] She added that even within the Guatemalan government, Árbenz "gave full compass to Indigenous, campesino, and labor demands" in contrast to Arévalo, who had remained suspicious of these movements.[149] Similarly, Greg Grandin stated that the land reform decree "represented a fundamental shift in the power relations governing Guatemala".[150] Árbenz himself once remarked that the agrarian reform law was "most precious fruit of the revolution and the fundamental base of the nation as a new country."[151] However, to a large extent the legislative reforms of the Árbenz and Arévalo administrations were reversed by the US-backed military governments that followed.[152]

In popular culture

The Guatemalan movie The Silence of Neto (1994), filmed on location in Antigua Guatemala, takes place during the last months of the government of Árbenz. It follows the life of a fictional 12-year-old boy who is sheltered by the Árbenz family, set against a backdrop of the struggle in which the country is embroiled at the time.[153]

The story of Árbenz's life and subsequent overthrow in the CIA sponsored coup d'état has been the subject of several books, notably PBSuccess: The CIA's covert operation to overthrow Guatemalan president Jacobo Arbenz June–July 1954[154] by Mario Overall and Daniel Hagedorn (2016), American Propaganda, Media, And The Fall Of Jacobo Arbenz Guzman by Zachary Fisher (2014),[155] as well as New York Times Best Seller The Devil's Chessboard by Author David Talbot (Harper Collins 2015). The Arbenz story was also the subject of the multi award-winning 1997 documentary by Andreas Hoessli Devils Don't Dream![156]

See also

Notes

- In order to run for election, the constitution required that Arana resign his military position by May 1950, and that his successor be chosen by Congress from a list submitted by the Consejo Superior de la Defensa, or CSD.[47] Elections for the CSD were scheduled for July 1949. The months before this election saw intense wrangling, as Arana supporters tried to gain control over the election process. Specifically, they wanted the election to be supervised by regional commanders loyal to Arana, rather than centrally dispatched observers.[47]

References

- Gleijeses 1992, p. 3.

- Martínez Peláez 1990, p. 842.

- LaFeber 1993, p. 77–79.

- Forster 2001, p. 81–82.

- Friedman 2003, p. 82–83.

- Hunt 2004, p. 255.

- Garcia Ferreira 2008, p. 60.

- Castellanos Cambranes, Julio. Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán: Por la Patria y la Revolución en Guatemala, 1951–1954 [Jacobo Arbenz Guzmán: For the Motherland and the Revolution in Guatemala, 1951–1954] (PDF). Copredeh. p. 90. ISBN 978-9929-8119-3-5. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- Gleijeses 1992, p. 134–137.

- Gleijeses 1992, p. 141.

- Streeter 2000, pp. 8–10.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 10–11.

- Forster 2001, pp. 12–15.

- Streeter 2000, p. 11.

- Forster 2001, p. 29.

- Streeter 2000, pp. 11–12.

- Immerman 1982, p. 34–37.

- Cullather 2006, p. 9–10.

- Rabe 1988, p. 43.

- Forster 2001, pp. 29–32.

- Gleijeses 1992, p. 15.

- McCreery 1994, pp. 316–317.

- Gleijeses 1992, p. 22.

- Immerman 1982, pp. 36–37.

- Forster 2001, p. 84.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 24–25.

- Forster 2001, p. 86.

- Immerman 1982, p. 39–40.

- Gleijeses 1992, p. 140.

- Immerman 1982, pp. 41–43.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 48–51.

- Forster 2001, pp. 89–91.

- Loveman & Davies 1997, pp. 126–127.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 28–29.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 30–31.

- Immerman 1982, pp. 45–45.

- Streeter 2000, p. 14.

- Gleijeses 1992, p. 36.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 48–54.

- Immerman 1982, pp. 46–49.

- Streeter 2000, pp. 15–16.

- Immerman 1982, p. 48.

- Sabino 2007, p. 9–24.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 51–57.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 58–60.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 59–63.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 59–69.

- Gleijeses 1992, p. 70.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 73–84.

- Gleijeses 1992, p. 74.

- Streeter 2000, pp. 15–17.

- Immerman 1982, pp. 60–61.

- Gleijeses 1992, p. 83.

- Immerman 1982, p. 62.

- Immerman 1982, pp. 62–62.

- Streeter 2000, p. 16.

- Forster 2001, p. 2.

- Gleijeses 1992, p. 124.

- Streeter 2000, p. 18.

- Fried 1983, p. 52.

- Gleijeses 1992, p. 149.

- Immerman 1982, p. 64.

- Gleijeses 1992, p. 49.

- Handy 1994, p. 84.

- Handy 1994, p. 85.

- Paterson 2009, p. 304.

- Handy 1994, p. 36.

- Schlesinger 2011.

- Malkin 2011.

- Chomsky 1985, pp. 154–160.

- Gleijeses 1992, p. 77.

- Gleijeses 1992, p. 134.

- Immerman 1982, pp. 62–63.

- Immerman 1982, p. 63.

- Streeter 2000, pp. 18–19.

- Forster 2001, pp. 98–99.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 50–60.

- Ibarra 2006.

- Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 55–59.

- Gleijeses 1992, p. 141–181.

- Gleijeses 1992, p. 181–379.

- Gleijeses 1992, p. 146–148.

- Immerman 1982, pp. 64–67.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 144–146.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 149–164.

- Smith 2000, p. 135.

- Grandin 2000, pp. 200–201.

- Gleijeses 1992, p. 155, 163.

- Forster 2001, p. 118.

- Immerman 1982, pp. 68–70.

- Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 65–68.

- Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 67–71.

- Immerman 1982, pp. 68–72.

- Immerman 1982, p. 73–76.

- Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, p. 71.

- Immerman 1982, pp. 75–82.

- Forster 2001, p. 136–137.

- Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 72–77.

- Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 90–97.

- Immerman 1982, pp. 82–100.

- Gaddis 1997, p. 177.

- Streeter 2000, p. 4.

- Immerman 1982, pp. 109–110.

- Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, p. 102.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 228–231.

- Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 100–101.

- Gleijeses 1992, p. 234.

- Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 106–107.

- Immerman 1982, pp. 122–127.

- Cohen, Rich (2012). The Fish that Ate the Whale. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. p. 186.

- Kornbluh 1997.

- Immerman 1982, pp. 141–143.

- Immerman 1982, pp. 162–165.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 259–262.

- Immerman 1982, pp. 144–150.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 280–285.

- Immerman 1982, pp. 155–160.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 300–311.

- Cullather 2006, pp. 87–89.

- Immerman 1982, p. 165.

- Cullather 2006, pp. 100–101.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 320–323.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 326–329.

- Cullather 2006, p. 97.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 330–335.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 342–345.

- Gleijeses 1992, pp. 345–349.

- Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, p. 201.

- Garcia Ferreira 2008, p. 56.

- Garcia Ferreira 2008, p. 62.

- prnewswire 2011.

- Garcia Ferreira 2008, pp. 64–65.

- Garcia Ferreira 2008, p. 66.

- Garcia Ferreira 2008, p. 54.

- Garcia Ferreira 2008, p. 55.

- Garcia Ferreira 2008, p. 68.

- Koeppel 2008, p. 153.

- Gleijeses 1992, p. 379.

- Garcia Ferreira 2008, p. 69.

- Garcia Ferreira 2008, pp. 70–72.

- Garcia Ferreira 2008, p. 72.

- Garcia Ferreira 2008, p. 72–73.

- Forster 2001, p. 221.

- New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/24/world/americas/24guatemala.html. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - . BBC http://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias/2011/10/111019_guatemala_arbenz_perdon_2_cch.shtml. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - IACHR 2011.

- Garcia Ferreira 2008, p. 74.

- Garcia Ferreira 2008, p. 61.

- Forster 2001, p. 19.

- Grandin 2000, p. 221.

- Grandin 2000, p. 239.

- Schlesinger & Kinzer 1999, pp. 190–204.

- Borrayo Pérez 2011, pp. 37–48.

- Overall, Mario; Hagedorn, Dan (2016). PBSuccess: The CIA's covert operation to overthrow Guatemalan president Jacobo Arbenz June–July 1954. ISBN 978-1910777893.

- American Propaganda, Media, And The Fall Of Jacobo Arbenz Guzman: American Propaganda, Popular Media, And The Fall Of Jacobo Arbenz Guzman. ISBN 3659528064.

- "Devils Don't Dream!".

Sources

- Borrayo Pérez, Gloria Catalina (2011). Análisis de contenido de la película "El Silencio de Neto" con base a los niveles histórico, contextual, terminológico, de presentación y el análisis de textos narrativos (PDF). Tesis (in Spanish). Guatemala: Escuela de Ciencias de la Comunicación de la Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chomsky, Noam (1985). Turning the Tide. Boston, Massachusetts: South End Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cullather, Nicholas (2006). Secret History: The CIA's Classified Account of its Operations in Guatemala 1952–54 (2nd ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5468-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Forster, Cindy (2001). The time of freedom: campesino workers in Guatemala's October Revolution. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-4162-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fried, Jonathan L. (1983). Guatemala in rebellion: unfinished history. Grove Press. p. 52.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Friedman, Max Paul (2003). Nazis and good neighbors: the United States campaign against the Germans of Latin America in World War II. Cambridge University Press. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-0-521-82246-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gaddis, John Lewis (1997). We Now Know, rethinking Cold War history. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-878070-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garcia Ferreira, Roberto (2008). "The CIA and Jacobo Arbenz: The story of a disinformation campaign". Journal of Third World Studies. United States. XXV (2): 59.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gleijeses, Piero (1992). Shattered hope: the Guatemalan revolution and the United States, 1944–1954. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02556-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grandin, Greg (2000). The blood of Guatemala: a history of race and nation. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2495-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Handy, Jim (1994). Revolution in the countryside: rural conflict and agrarian reform in Guatemala, 1944–1954. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4438-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hunt, Michael (2004). The World Transformed. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-937234-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "IACHR Satisfied with Friendly Settlement Agreement in Arbenz Case Involving Guatemala". Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- Ibarra, Carlos Figueroa (June 2006). "The culture of terror and Cold War in Guatemala". Journal of Genocide Research. 8 (2): 191–208. doi:10.1080/14623520600703081.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Immerman, Richard H. (1982). The CIA in Guatemala: The Foreign Policy of Intervention. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-71083-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Koeppel, Dan (2008). Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World. New York: Hudson Street Press. p. 153. ISBN 9781101213919.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kornbluh, Peter; Doyle, Kate, eds. (May 23, 1997) [1994], "CIA and Assassinations: The Guatemala 1954 Documents", National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 4, Washington, D.C.: National Security Archive

- LaFeber, Walter (1993). Inevitable revolutions: the United States in Central America. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 77–79. ISBN 978-0-393-30964-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Loveman, Brian; Davies, Thomas M. (1997). The Politics of antipolitics: the military in Latin America (3rd, revised ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8420-2611-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Malkin, Elizabeth (October 20, 2011). "An Apology for a Guatemalan Coup, 57 Years Later". The New York Times. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- Martínez Peláez, Severo (1990). La Patria del Criollo (in Spanish). México: Ediciones En Marcha. p. 858.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McCreery, David (1994). Rural Guatemala, 1760–1940. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2318-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Paterson, Thomas G. (2009). American Foreign Relations: A History, Volume 2: Since 1895. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-547-22569-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- prneswire.com (October 11, 2011). "Guatemalan government issues official apology to deposed former president Jacobo Arbenz's family for Human Rights Violtions, 57 years later". Retrieved September 19, 2014.

- Rabe, Stephen G. (1988). Eisenhower and Latin America: The Foreign Policy of Anticommunism. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-4204-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sabino, Carlos (2007). Guatemala, la historia silenciada (1944–1989) (in Spanish). Tomo 1: Revolución y Liberación. Guatemala: Fondo Nacional para la Cultura Económica.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schlesinger, Stephen; Kinzer, Stephen (1999). Bitter Fruit: The Story of the American Coup in Guatemala. David Rockefeller Center series on Latin American studies, Harvard University. ISBN 978-0-674-01930-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schlesinger, Stephen (June 3, 2011). "Ghosts of Guatemala's Past". The New York Times. Retrieved July 21, 2014.

- Smith, Peter H. (2000). Talons of the Eagle: Dynamics of U.S.-Latin American Relations. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512997-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Streeter, Stephen M. (2000). Managing the counterrevolution: the United States and Guatemala, 1954–1961. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-89680-215-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

Books

- Arévalo Martinez, Rafael (1945). ¡Ecce Pericles! (in Spanish). Guatemala: Tipografía Nacional.

- Chapman, Peter (2009). Bananas: How the United Fruit Company Shaped the World. Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84767-194-3.

- Cullather, Nicholas (May 23, 1997). "CIA and Assassinations: The Guatemala 1954 Documents". National Security Archive Electronic. Briefing Book No. 4. National Security Archive. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Dosal, Paul J. (1993). Doing Business With the Dictators: A Political History of United Fruit in Guatemala, 1899–1944. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8420-2590-4.

- Handy, Jim (1984). Gift of the devil: a history of Guatemala. South End Press. ISBN 978-0-89608-248-9.

- Holland, Max (2004). "Operation PBHistory: The Aftermath of SUCCESS". International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence. 17 (2): 300–332. doi:10.1080/08850600490274935.

- Jonas, Susanne (1991). The battle for Guatemala: rebels, death squads, and U.S. power (5th ed.). Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-0614-8.

Government/NGO reports

- CIA file about Operations against Jacob Árbenz

News

- From Árbenz to Zelaya: Chiquita in Latin America, Democracy Now!, July 21, 2009

- Guatemala to Restore Legacy of a President the US Helped Depose, by Elisabeth Malkin, Published: May 23, 2011

External links

- International Jose Guillermo Carrillo Foundation

- Jacobo Árbenz Biography brought to you by the United Fruit Company's "United Fruit Historical Society"

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Juan José Arévalo |

President of Guatemala 1951–1954 |

Succeeded by Carlos Enrique Díaz de León |