Germany–United States relations

Germany–United States relations, also referred to as German–American relations, are the bilateral relations between Germany and the United States. German–American relations are the historic relations between Germany and the United States at the official level, including diplomacy, alliances and warfare. The topic also includes economic relations such as trade and investments, demography and migration, and cultural and intellectual interchanges since the 1680s.

| |

Germany |

United States |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| German Embassy, Washington, D.C. | United States Embassy, Berlin |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador Emily Haber | Ambassador Richard Grenell |

Overview

Before 1900, the main factors in German-American relations were very large movements of immigrants from Germany to American states (especially Pennsylvania, the Midwest, and central Texas) throughout the 18th and the 19th centuries.[1]

There also was a significant movement of philosophical ideas that influenced American thinking. German achievements in public schooling and higher education greatly impressed American educators; the American education system was based on the Prussian education system. Thousands of American advanced students, especially scientists and historians, studied at elite German universities. There was little movement in the other direction: few Americans ever moved permanently to Germany, and few German intellectuals studied in America or moved to the United States before 1933. Economic relations were of minor importance before 1920. Diplomatic relations were friendly but of minor importance to either side before the 1870s.[2]

After the Unification of Germany in 1871, Germany became a major world power. Both nations built world-class navies and began imperialistic expansion around the world. That led to a small-scale conflict over the Samoan islands: the Second Samoan Civil War. A crisis in 1898, when Germany and the United States disputed over who should take control, was resolved with the Tripartite Convention in 1899 when the two nations divided up Samoa between them to end the conflict.[3]

After 1898, the US itself became much more involved in international diplomacy and found itself sometimes in disagreement but more often in agreement with Germany. In the early 20th century, the rise of the powerful German Navy and its role in Latin America and the Caribbean troubled American military strategists. Relations were sometimes tense, as in the Venezuelan crisis of 1902–03, but all incidents were peacefully resolved.[4]

The US tried to remain neutral in the First World War, but it provided far more trade and financial support to Britain and the Allies, which controlled the Atlantic routes. Germany worked to undermine American interests in Mexico. In 1917, the German offer of a military alliance against the US in the Zimmermann Telegram contributed to the American decision for war.[5] German submarine attacks on British shipping, especially the sinking of the passenger liner Lusitania without allowing the civilian passengers to reach the lifeboats, outraged US public opinion. Germany agreed to US demands to stop such attacks but reversed its position in early 1917 to win the war quickly since it mistakenly thought that the US military was too weak to play a decisive role.

The US public opposed the punitive 1919 Versailles Treaty, and both countries signed a separate peace treaty in 1921. In the 1920s, American diplomats and bankers provided major assistance to rebuilding the German economy. When Hitler and the Nazis took power in 1933, American public opinion was highly negative. Relations between the two nations turned sour after 1938.

Large numbers of intellectuals, scientists, and artists found refuge from the Nazis in the United States, but American immigration policy strictly limited the number of Jewish refugees. The US provided significant military and financial aid to Britain and France. Germany declared war on the United States in December 1941, and Washington made the defeat of Nazi Germany its highest priority. The United States played a major role in the occupation and reconstruction of Germany after 1945. The USs provided billions of dollars in aid by the Marshall Plan to rebuild the West German economy. The two nations relationship became very positive, in terms of democratic ideals, anti-communism, and high levels of economic trade.

Today, the US is one of Germany's closest allies and partners outside of the European Union.[6] The people of the two countries see each other as reliable allies but disagree on some key policy issues. Americans want Germany to play a more active military role, but Germans strongly disagree.[7]

Country comparison

| Coat of Arms |  |

.svg.png) |

| Flag |  |

|

| Population | 82,800,000 | 330,132,000 |

| Area | 357,168 km² (137,847 sq mi) | 9,526,468 km² (3,794,066 sq mi)[8] |

| Population density | 232/km² (601/sq mi) | 31/km² (80/sq mi) |

| Capital | Berlin | Washington, D.C. |

| Largest city | Berlin – 3,690,000 (6,004,857 Metro) | New York City – 8,175,133 (19,006,798 Metro) |

| Major Cities | Berlin Hamburg Munich Cologne Frankfurt am main Stuttgart Düsseldorf |

New York City Los Angeles Chicago Houston Philadelphia San Francisco Miami |

| Government | Federal parliamentary republic | Federal presidential constitutional republic |

| First Leader | Konrad Adenauer | George Washington |

| Current Leader | Angela Merkel | Donald Trump |

| Official languages | German (de facto and de jure) | English (de facto) |

| Main religions | 57.9% Christianity, 36.2% non-religious, 4.9% Islam, 1.0% other[9] | 69% Christianity, 22.8% non-religious, 1.9% Judaism, 1.6% Mormonism, 0.9% Islam, 0.7% Buddhism, 0.7% Hinduism[10] |

| Ethnic groups | 81.3% German, 3.4% Turkish, 2.3% Polish, 1.5% Russian, 11.5% other | 74% White American, 13.4% African American, 6.5% Some other race, 4.4% Asian American, 2% Two or more races, 0.7% Native American or Native Alaskan, 0.14% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander |

| GDP (nominal) | $3.65 trillion[11] | $19.36 trillion[12] |

| German Americans | 99,891 American born people living in Germany[13] | 50,764,352 people of German ancestry living in the USA |

| Military expenditures | $41.3 billion (FY 2017) (see Bundeswehr) | $582.7 billion (FY 2017) (see Military budget of the United States) |

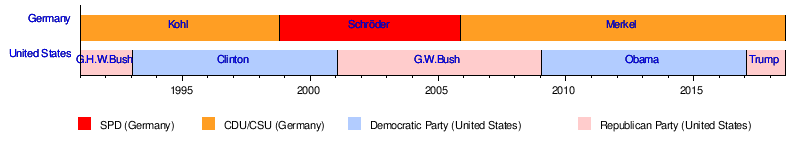

Leaders of Germany and United States from 1991

History

German immigration to the United States

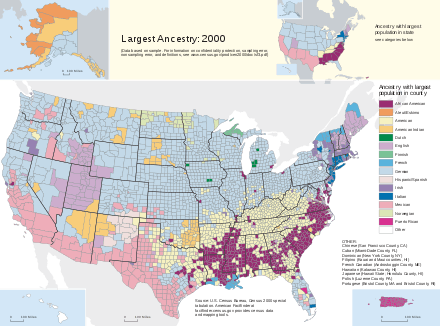

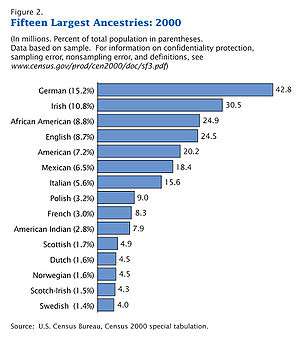

For over three centuries, immigration from Germany accounted for a large share of all American immigrants. As of the 2000 US Census, more than 20% of all Americans, and 25% of white Americans, claim German descent. German-Americans are an assimilated group which influences political life in the US as a whole. They are the most common self-reported ethnic group in the Northern United States, especially in the Midwest. In most of the South, German Americans are less common, with the exception of Florida and Texas.

1683–1848

The first records of German immigration date back to the 17th century and the foundation of Germantown, now part of Philadelphia, in 1683. Immigration from Germany reached its first peak between 1749 and 1754, when approximately 37,000 Germans came to North America.

1848–1914

Since 1848, about seven million Germans have emigrated to the United States. Many of them settled in the cities of Baltimore, Chicago, Detroit and New York City.

The failed German Revolutions of 1848 into 1849 (accompanied by similar upheavals that same pivotal year in the rest of Europe) accelerated emigration from Germany and the German Confederation. Those Germans who left as a result of the revolution were called the Forty-Eighters. Between the revolution and the start of World War I (1914–1918), over 70 years later, over one million Germans settled in the United States. They endured hardship as a result of overcrowded ships, and typhus fever spread rapidly throughout the ships due to the cramped conditions. On average, it took Germans six months to get to the New World, and many died on the journey.

By 1890 more than 40 percent of the population of the cities of Cleveland, Milwaukee, Hoboken and Cincinnati were of German origin. By the end of the 19th century, Germans formed the largest self-described ethnic group in the United States and their customs became a strong element in American society and culture.

Political participation of German-Americans was focused on involvement in the labor movement. Germans in America had a strong influence on the labor movement in the United States. Newly-founded labor unions enabled German immigrants to improve their working conditions and to integrate into American society.

Since 1914

A combination of patriotism and anti-German sentiment along with civil strife during both world wars caused most German-Americans to cut their former ties and assimilate into mainstream American culture with disbanding of German cultural, genealogical, and historical groups; the study and teaching of the German language and history in high schools, colleges, universities; and the removal of several German-related monuments and placenames. During Nazi Germany and the Third Reich (1933–1945) before and during World War II (1939–1945), Germany had another major emigration wave of German Jews and other political anti-Nazi refugees leaving the Reich and even the continent.

Today, German-Americans form the largest self-reported ancestry group in the United States[14] with California and Pennsylvania having the highest number of German Americans.

Diplomacy and trade

During the American Revolution (1775–1783), King Frederick the Great of Prussia strongly hated the British, who had abandoned him in 1761, during the Seven Years' War (1756–1763). He now favored France and impeded Britain's war effort in subtle ways, such as blocking the passage of Hessians soldiers. However, the importance of British trade and the risk of attack from Austria made him pursue a peace policy and maintain an official strict neutrality.[15][16]

After the war, direct trade between the American ports of Baltimore, Norfolk, and Philadelphia and the old Hanseatic League ports of Bremen, Hamburg, and Lübeck grew steadily. Americans exported tobacco, rice, cotton, sugar, imported textiles, metal products, colognes, brandies, and toiletries. The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) and increasing instability in the German Confederation states led to a decline in the economic relationships between the United States and the Hanse. The level of trade never came close to matching the trade with Britain and faltered because the US delayed a commercial treaty until 1827. US diplomacy was ineffective, but the commercial consuls, local businessmen, handled their work so well that the US successfully developed diplomatic ties with Prussia. However, trade was minimal.[17]

It was the Kingdom of Prussia under Frederick William III that took the initiative in sending a trade experts to Washington, DC, in 1834. The first permanent American diplomat came in 1835, when Henry Wheaton was sent to Prussia. The United States Secretary of State said that "not a single point of controversy exists between the two countries calling for adjustment; and that their commercial intercourse, based upon treaty stipulations, is conducted upon those liberal and enlightened principles of reciprocity... which are gradually making their way against the narrow prejudices and blighting influences of the prohibitive system."[18]

During the American Civil War (1861–1865), all of the German states favored the northern Union but played no major role.

After 1871

In 1876, the German commissioner for the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia stated that the German armaments, machines, arts, and crafts on display were of inferior quality to British and American products. Germany industrialized rapidly after unification under Chancellor Otto von Bismarck in 1870–1871, but its competition was more with Britain than with the US. It bought increasing amounts of American farm products, especially cotton, wheat and tobacco, but tried to block American meat.[19]

Porkwar and protectionism

In 1880, ten European countries (Germany, Italy, Portugal, Greece, Spain, France, Austria-Hungary, Turkey, Romania, and Denmark) imposed a ban on importation of American pork in the 1880s. They pointed to vague reports of trichinosis that supposedly originated with American hogs.[20] At issue was over 1.3 billion pounds of pork products in 1880, with a value of $100 million annually. European farmers were angry at cheap American food overrunning their home markets for wheat, pork, and beef; demanded for their governments to fight back; and called for a boycott.

European manufacturing interests were also threatened by growing American industrial exports, and were angry at the high American tariff on imports from European factories. Chancellor Bismarck took a hard line, rejected the pro-trade German businessmen, and refused to join in scientific studies proposed by President Chester A. Arthur. American investigations reported that American pork was safe. Bismarck, because of his political base of German landowners, insisted on protection and ignored the leading German expert, Professor Rudolf Virchow, who condemned the embargo as unjustified.[21][22]

American public opinion grew angry at Berlin. President Grover Cleveland rejected retaliation, but it was threatened by his successor, Benjamin Harrison, who charged Whitelaw Reid, minister to France, and William Walter Phelps, minister to Germany, to end the boycott without delay. Harrison also persuaded Congress to enact the Meat Inspection Act of 1890 to guarantee the quality of the export product.

The president used his Agriculture Secretary Jeremiah McLain Rusk to threaten Germany with retaliation by initiating an embargo against Germany's popular beet sugar. That proved decisive for Germany to relent in September 1891. Other nations soon followed, and the boycott was soon over.[23][24]

Samoan crisis

After German unification in 1871, the new, large, rich, and ambitious German Empire built a world-class navy rising to third place, behind British and American navies. Bismarck himself distrusted imperialism, but he reversed course in the face of public and elite opinion that favored imperialistic expansion around the world. In 1889, the US, Britain and Germany were locked in an petty dispute over control of the Samoan Islands, in the Pacific.[25] The issue emerged in 1887 when the Germans tried to establish control over the island chain and President Cleveland responded by sending three naval vessels to defend the Samoan government. American and German warships faced off but all were badly damaged by the 1889 Apia cyclone of March 15–17, 1889.[26] The delegates agreed to meet in Berlin to resolve the crisis.

Chancellor Bismarck decided to ignore the small issues involved and improve relations with Washington and London. The result was the Treaty of Berlin, which established a three-power protectorate in Samoa. The three powers agreed to Western Samoa's independence and neutrality. Historian George H. Ryden argues that Harrison played a key role in determining the status of this Pacific outpost by taking a firm stand on every aspect of Samoa conference negotiations, which included the selection of the local ruler, the refusal to allow an indemnity for Germany, and the establishment of the three-power protectorate, a first for the U.S.[27][28] A serious long-term result was an American distrust of Germany's foreign policy after Bismarck was forced out in 1890.[29]When unrest continued, international tensions flared in 1899. Berlin pulled back the treaty was annulled and 0.Western Samoa became a German protectorate. It was seized by New Zealand in the First World War. [30][31]

Caribbean

In the late 19th century, the Kaiserliche Marine (German Navy) sought to establish a coaling station somewhere in the Caribbean Sea area. Imperial Germany was rapidly building a blue-water navy, but coal-burning warships needed frequent refueling and so needed to operate within range of a coaling station. Preliminary plans were vetoed by Bismarck, who did not want to antagonize the US, but he was ousted in 1890 by the new emperor, Wilhelm II, and the Germans kept looking.[32]

German naval planners from 1890 to 1910 denounced the 1820s Monroe Doctrine as a self-aggrandizing legal pretension and were even more concerned with the possible American canal at Panama, in Central America, as it would lead to full American hegemony in the Caribbean. The stakes were laid out in the German war aims proposed by the German Navy in 1903: a "firm position in the West Indies," a "free hand in South America," and an official "revocation of the Monroe Doctrine" would provide a solid foundation for "our trade to the West Indies, Central and South America."[33] By 1900, American "naval planners were obsessed with German designs in the Western Hemisphere and countered with energetic efforts to secure naval sites in the Caribbean."[34]

In the Venezuela Crisis of 1902–1903, Britain and Germany sent warships to blockade Venezuela after it defaulted on its foreign loan repayments. Germany intended to land troops and occupy Venezuelan ports, but US President Theodore Roosevelt (1901–1909) forced the Germans to back down by sending his own fleet and threatening war if the Germans landed.[35]

By 1904, German naval strategists had turned its attention to Mexico, where they hoped to establish a naval base in a Mexican port on the Caribbean. They dropped that plan, but it became active again after 1911, the start of the Mexican Revolution and subsequent Mexican Civil War.[36]

1900-1919

Venezuelan defaulted on its foreign loan repayments in 1902, and Britain and Germany sent warships to blockade its ports and force repayment. Germany intended to land troops and occupy Venezuelan ports, but President Theodore Roosevelt forced the Germans to back down by sending his own fleet and threatening war if the Germans landed.[37] The Venezuela episode focused American attention on Kaiser William II, who was increasingly erratic and aggressive. The media highlighted his militarism and belligerent speeches and imperialistic goals. At the same time, the British were becoming increasingly friendly toward the United States in world affairs. American opinion became more negative toward Germany than towards any other country in Europe.[38]

World War I

World War I started in August 1914, and the US insisted on neutrality. US President Woodrow Wilson's highest priority was to broker peace talks and used his trusted aide, Colonel House. Apart from an Anglophile element urging early support for Britain, US public opinion reflected that of the president: the sentiment for neutrality was particularly strong among Irish Americans, German Americans, and Scandinavian Americans as well as poor white southern farmers, cultural leaders, Protestant churchmen, and women in general.[39] The British argument that the Allies were defending civilization against a German militaristic onslaught gained support after reports of atrocities in Belgium in 1914 and, following the sinking of the passenger liner RMS Lusitania in 1915, US citizens increasingly came to see Germany as the aggressor who had to be stopped. Former President Theodore Roosevelt and many Republicans were war hawks, and demanded rapid American armament

Wilson insisted on neutrality and minimized wartime preparations to be able to negotiate for peace. After the British ship Lusitania was sunk, with over 100 American passengers drowned, Wilson demanded for German submarines to allow passengers and crew to reach their lifeboats before ships were sunk. Germany reluctantly agreed, but in January 1917, it decided that a massive infantry attack on the Western Front, coupled with a full-scale attack on all food shipments to Europe, would prove decisive. It realized the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare almost certainly meant war with the United States, but it calculated that the U.S. Armed Forces would take years to mobilize and arrive, when Germany would have already won. Germany reached out to Mexico with the Zimmermann Telegram, offering a military alliance against the United States, hoping the United States would diverge most of its attention to attacking Mexico. London intercepted the telegram, the contents of which outraged American opinion.[40]

.jpg)

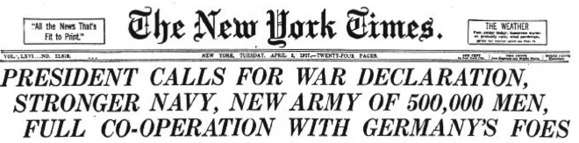

Wilson called on Congress to declare war on Germany in April 1917. The United States expected to provide money, munitions, food, and raw materials but did not expect to send large troop contingents until it realized how weak the Allies were on the Western Front. After the exit of Russia from the war in late 1917, Germany could reallocate 600,000 experienced troops to the Western Front. but by summer, American troops were arriving at the rate of 10,000 a day, every day, replacing all the Allied losses while the German Army shrank day by day until it finally collapsed in November 1918. On the homefront, the loyalty of German-Americans was frequently challenged. Any significant German cultural impact was seen with intense hostility and suspicion. Germany was portrayed as a threat to American freedom and way of life.

Inside Germany, the United States was another enemy and denounced as a false liberator that wanted to dominate Europe itself. As the war ended, however, the German people embraced Wilsonian promises of the just peace treaty. At the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, Wilson used his enormous prestige and co-operated with British Prime Minister David Lloyd George to block some of the harshest French demands against Germany in the Treaty of Versailles. Wilson devoted most of his attention to establishing the League of Nations, which he felt would end all wars. He also signed a treaty with France and Britain to guarantee American support to prevent Germany from invading France again. Wilson refused all compromises with the Republicans, who controlled Congress, and so the United States neither ratified the Treaty of Versailles nor joined the League of Nations.[41]

Interwar period

1920s

Economic and diplomatic relations were positive during the 1920s. The US government rejected the harsh anti-German Versailles Treaty of 1920, signed a new peace treaty that involved no punishment for Germany, and worked with Britain to create a viable Euro-Atlantic peace system.[42] Ambassador Alanson B. Houghton (1922–1925) believed that world peace, European stability, and American prosperity depended upon a reconstruction of Europe's economy and political systems. He saw his role as promoting American political engagement with Europe. He overcame US opposition and lack of interest and quickly realized that the central issues of the day were all entangled in economics, especially war debts owed by the Allies to the United States, reparations owed by Germany to the Allies, worldwide inflation, and international trade and investment. Solutions, he believed, required new US policies and close co-operation with Britain and Germany. He was a leading promoter of the Dawes Plan.[43]

Although the high culture of Germany looked down upon American culture, jazz was widely accepted by the younger generation. Hollywood had an enormous influence, as did the Detroit model of industrial efficiency.[44][45][46]

German influence on American society was limited during that period. The flow of migration into the United States was small, and young American scholars seldom attended German universities for graduate work.

The U.S. government took the lead through the Dawes Plan and the Young Plan.[47]

New York banks played a major role in financing the rebuilding of the Germany economy.[48][49] The German right was suspicious of modernity, as represented by the United States.[50]

Nazi era 1933–41

Public opinion in the US was strongly negative toward Nazi Germany and Adolf Hitler, but there was also a strong aversion to war and to entanglement in European politics.[51] The Roosevelt administration publicly hailed the Munich Agreement of 1938 for avoiding war but privately realized it was only a postponement that called for rapid rearming.[52] Formal relations were cool until November 1938 and then turned very cold. The key event was American revulsion against Kristallnacht, the nationwide German assault on Jews and Jewish institutions. Religious groups which had been pacifistic also turned hostile.[53] While the total flow of refugees from Germany to the US was relatively small during the 1930s, many intellectuals escaped and resettled in the United States.[54] Many were Jewish.[55] Catholic universities were strengthened by the arrival of German Catholic intellectuals in exile, such as Waldemar Gurian at Notre Dame University.[56]

The American major film studios censored and edited films so that they could be exported to Germany.[57][58]

Nazi Germany

As World War II began with the German invasion of Poland in September 1939, the US was officially neutral until December 11, 1941 when Germany declared war on the US.. Roosevelt's foreign policy strongly favored Britain, France and the other European democracies over Germany in 1939 to 1941. The US played a central role in the defeat of the Axis powers and so relations between Berlin and Washington, DC, were inevitably at their lowest point. Germany used American participation as one of the leaders of the Allies for extensive propaganda value, and the infamous "LIBERATORS" poster from 1944 may be the most powerful example. In contrast, Roosevelt was, as early as mid-March 1941,[59] quite acutely aware of Hitler's views about the United States, but Roosevelt needed to balance the dueling issues of preparing the United States for its likely involvement in a global conflict and the continuing strong desire by many Americans to avoid war at all costs until the consequences of the attack on Pearl Harbor settled the issue.

In the aforementioned poster, which is shown in this article, the United States was depicted as a monstrous, vicious war machine seeking to destroy European culture. The poster alluded to many negative aspects of American history, including the Ku Klux Klan, the oppression of Native Americans, and the lynching of blacks. The poster condemned American capitalism and America's perceived dominance by Judaism and showed American bombs destroying a helpless European village. However, the US launched several propaganda campaigns in return towards Nazi Germany that often portrayed Nazi Germany as a warmongering country, with inferior morales and brainwashing schemes.

Cold War

Following the defeat of the Third Reich, American forces were one of the occupation powers in postwar Germany. In parallel to denazification and "industrial disarmament" American citizens fraternized with Germans. The Berlin Airlift from 1948–1949 and the Marshall Plan (1948–1952) further improved the Germans' perception of Americans.

West Germany

The emergence of the Cold War made the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) the frontier of a democratic Western Europe and American military presence became an integral part in West German society. The US presence may have helped smooth over possibly awkward postwar relationships if they had not come under the aegis of the biggest intact army and economy. That lessened the lag before the formation of the precursors to today's EU and may be seen as a silent benefit of Pax Americana. During the Cold War, West Germany developed into the largest economy in Europe and West German-US relations developed into a new transatlantic partnership. Germany and the US shared a large portion of their culture, established intensive global trade environment, and continued to co-operate on new high technologies. However, tensions remained between differing approaches on both sides of the Atlantic. The fall of the Berlin Wall and the subsequent German reunification marked a new era in German-American co-operation.

East Germany

Relations between the United States and East Germany were hostile. The United States followed the Adenauer's Hallstein Doctrine of 1955, which declared that recognition by any country of East Germany would be treated as an unfriendly act by West Germany. Relations between the Germanie thawed somewhat in the 1970s, as part of the overall détente between East and West. United States recognized East Germany officially in September 1974, when Erich Honecker was the leader of the ruling Socialist Unity Party. To ward off the risk of internal liberalization on his regime, Honecker enlarged the Stasi from 43,000 to 60,000 agents.[60]

East Germany imposed an official ideology that was reflected in all its media and all the schools. The official line stated that the United States had caused the breakup of the coalition against Adolf Hitler and had become the bulwark of reaction worldwide, with a heavy reliance on warmongering for the benefit of the "terrorist international of murderers on Wall Street." East Germans had a heroic role to play as a frontline against the evil Americans. However few Germans believed it since had seen enough of the Soviets since 1945, and half-a-million Soviets were still stationed in East Germany as late as 1989. Furthermore, East Germans were exposed to information from relatives in the West, Radio Free Europe broadcasts from the US, and the West German media.

The official Communist media ridiculed the modernism and cosmopolitanism of American culture, and denigrated the features of the American way of life, especially jazz music and rock 'n roll. The East German regime relied heavily on its tight control of youth organizations to rally them, with scant success, against American popular culture. The older generations were more concerned with the poor quality of food, housing, and clothing, which stood in dramatic contrast to the prosperity of West Germany. Professionals in East Germany were watched for any sign of deviation from the party line; their privileges were at risk. The choice was to comply or to flee to West Germany, which was relatively easy before the crackdown and the Berlin Wall of 1961.[61] Americans saw East Germany simply as a puppet of Moscow, with no independent possibilities.

Reunified Germany

During the early 1990s, the reunified Germany was called a "partnership in leadership" as the US emerged as the world's sole superpower.

Germany's effort to incorporate any major military actions into the slowly-progressing European Security and Defence Policy did not meet the expectations of the U.S. during the Gulf War. After the September 11 attacks, German-American political relations were strengthened in an effort to combat terrorism, and Germany sent troops to Afghanistan as part of the NATO force. Yet, discord continued over the Iraq War, when German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder and Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer made efforts to prevent war and did not join the US and the UK, which both led multinational force in Iraq.[62][63] Anti-Americanism rose to the surface after the attacks of 11 September 2001 as hostile German intellectuals argued there were ugly links between globalization, Americanization, and terrorism.[64]

In response to the 2013 mass surveillance disclosures, Germany cancelled the 1968 intelligence sharing agreement with the US and UK.[65]

In July 2014, two Bundesnachrichtendienst officials were arrested by federal prosecutors for allegedly spying on the German government for the CIA. Chancellor Angela Merkel asked the coordinator of CIA activity at the U.S. Embassy in Berlin to leave his diplomatic post.[66] In response to the arrests, Merkel said, "Viewed with good common sense, spying on friends and allies is a waste of energy. In the cold war it may have been the case that there was mutual mistrust. Today we live in the 21st century."[67] The arrests followed the revelation that the NSA tapped the chancellor's cellphone.[68] German attempts to be included in the non-spying pact the US has with the UK, New Zealand, Australia and Canada were fruitless.[69] Merkel on 18 July 2014 said trust could only be restored through talks and Germany would seek to have such talks. She reiterated the U.S. was Germany's most important ally, and nothing about their relationship would change.[70] Nevertheless, German government officials in Berlin strengthened counterintelligence and planned new security measures in anticipation of prolonged frosty relations with the United States.[71]

In May 2017, Angela Merkel met with US President Donald Trump. Trump's statements that the U.S. had been taken advantage of in trade deals during previous administrations had already strained relations with several EU countries and other American allies. Without mentioning Trump specifically, Merkel said after a NATO summit "The times when we could completely rely on others are, to an extent, over,"[72] This came after Trump had said "The Germans are bad, very bad" and "See the millions of cars they are selling to the U.S. Terrible. We will stop this."[73]

Perceptions and values in the two countries

The exploits of gunslingers on the American frontier played a major role in American folklore, fiction and film. The same stories became immensely popular in Germany, which produced its own novels and films about the American frontier. Karl May (1842–1912) was a German writer best known for his adventure novels set in the American Old West. His main protagonists are Winnetou and Old Shatterhand.[74][75] The German fascination with Native Americans dates to the early 19th century, with a volumous literature. Typical writings focus on "Indianness" and authenticity.[76]

Germany and the US are civil societies. Germany's philosophical heritage and American spirit for "freedom" interlock to a central aspect of Western culture and Western civilization. Even though developed under different geographical settings, the Age of Enlightenment is fundamental to the self-esteem and understanding of both nations.

The American-led invasion of Iraq changed the perception of the US in Germany significantly. A 2013 BBC World Service poll shows found that 35% find American influence to be positive while 39% view it to be negative.[77] Both countries differ in many key areas, such as energy and military intervention.

A survey conducted on behalf of the German embassy in 2007 showed that Americans continued to regard Germany's failure to support the war in Iraq as the main irritant in relations between the two nations. The issue was of declining importance, however, and Americans still considered Germany to be their fourth most important international partner behind the United Kingdom, Canada and Japan. Americans considered economic cooperation to be the most positive aspect of US-German relations with a much smaller role played by Germany in U.S. politics.[78]

Among the nations of Western Europe, German public perception of the US is unusual in that it has continually fluctuated back and forth from fairly positive in 2002 (60%), to considerably negative in 2007 (30%), back to mildly positive in 2012 (52%), and back to considerably negative in 2017 (35%)[79] reflecting the sharply polarized and mixed feelings of the German people for the United States.

Anti-Americanism

During the Cold War, anti-Americanism was the official government policy in East Germany, and dissenters were punished. In West Germany, anti-Americanism was the common position on the left, but the majority praised the United States as a protector against communism and a critical ally in rebuilding the nation.[80] After 1990, the Communist Party in the East struggled under a new name, "Die Linke", and maintained their old anti-American position. Today, it warns that America is plotting to spoil Germany's friendly relationship with Russia. Germany's refusal to support the American-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 was often seen as a manifestation of anti-Americanism.[81] Anti-Americanism had been muted on the right since 1945, but reemerged in the 21st century especially in the Alternative for Germany (AfD) party that began in opposition to European Union, and now has become both anti-American and anti-immigrant. Annoyance or distrust of the Americans was heightened in 2013 by revelations of American spying on top German officials, including Chancellor Angela Merkel.[82]

Military relations

History

German-American military relations began in the Revolution when German troops fought on both sides. Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, a former Captain in the Prussian Army, was appointed Inspector General of the Continental Army and played the major role in training American soldiers to the best European standards. Von Steuben is considered to be one of the founding fathers of the United States Army.

Another German that served during the American Revolution was Major General Johann de Kalb, who served under Horatio Gates at the Battle of Camden and died as a result of several wounds he sustained during the fighting.

About 30,000 German mercenaries fought for the British, with 17,000 hired from Hesse, about one in four of the adult male population of the principality. The Hessians fought under their own officers under British command. Leopold Philip de Heister, Wilhelm von Knyphausen, and Baron Friedrich Wilhelm von Lossberg were the principal generals who commanded these troops with Frederick Christian Arnold, Freiherr von Jungkenn as the senior German officer.[83]

German Americans have been very influential in the American military. Some notable figures include Brigadier General August Kautz, Major General Franz Sigel, General of the Armies John J. Pershing, General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower, Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz, and General Norman Schwarzkopf, Jr..

Today

The United States established a permanent military presence in Germany during the Second World War that continued throughout the Cold War, with a peak level of over 274,000 U.S. troops stationed in Germany in 1962,[84] and was drawn down in the early 21st century. The last American tanks were withdrawn from Germany in 2013,[85] but they returned the following year to address a gap in multinational training opportunities.[86] The U.S. had 35,000 American troops in Germany in 2017.[84]

Germany and the United States are joint NATO members. Both nations have cooperated closely in the War on Terror, for which Germany provided more troops than any other nation. Germany hosts the headquarters of the US Africa Command and the Ramstein Air Base, a U.S. Air Force base.[87]

The two nations had opposing public policy positions in the War in Iraq; Germany blocked US efforts to secure UN resolutions in the buildup to war, but Germany quietly supported some US interests in southwest Asia. German soldiers operated military biological and chemical cleanup equipment at Camp Doha in Kuwait; German Navy ships secured sea lanes to deter attacks by Al Qaeda on U.S. Forces and equipment in the Persian Gulf; and soldiers from Germany's Bundeswehr deployed all across southern Germany to US military bases to conduct force protection duties in place of German-based U.S. Soldiers who were deployed to the Iraq War. The latter mission lasted from 2002 until 2006, by which time nearly all these Bundeswehr were demobilized.[88] U.S. soldiers wounded in Iraq received medical treatment at Germany's Landstuhl Regional Medical Center.[87]

In March 2019, Trump was reportedly drafting a demand several countries, including Germany, to pay the United States 150% of the cost of the American troops deployed on their soil. The proposed demand was criticized by experts. Douglas Lute, a retired general and former US ambassador to NATO, said that Trump was using "a misinformed narrative that these facilities are there for the benefits of those countries. The truth is they're there and we maintain them because they're in our interest."[89]

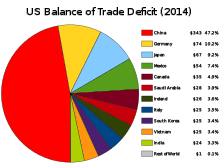

Economic relations

Economic relations between Germany and the United States are average. The Transatlantic Economic Partnership between the US and the EU, which was launched in 2007 on Germany's initiative, and the subsequently created Transatlantic Economic Council open up additional opportunities. The US is Germany's principal trading partner outside the EU and Germany is the US's most important trading partner in Europe. In terms of the total volume of U.S. bilateral trade (imports and exports), Germany remains in fifth place, behind Canada, China, Mexico, and Japan. The US ranks fourth among Germany's trading partners, after the Netherlands, China and France. At the end of 2013, bilateral trade was worth $162 billion.[90]

Germany and the US are important to each other as investment destinations. At the end of 2012, bilateral investment was worth $320 billion, German direct investment in the US amounting to $199 billion and U.S. direct investment in Germany $121 billion. At the end of 2012, US direct investment in Germany stood at approximately $121 billion, an increase of nearly 14% over the previous year (approximately $106 billion). During the same period, German direct investment in the US amounted to some $199 billion, below the previous year's level (approximately $215 billion). Germany is the eighth largest foreign investor in the US, after the United Kingdom, Japan, the Netherlands, Canada, France, Switzerland, and Luxembourg, and ranks eleventh as a destination for US foreign direct investment.

In 2019 the United States Senate[91] announced intention of passing controversial legislation which threatened to place sanctions on German or European Union companies which work to complete a petrol-chemical pipeline between Germany and Russia.[92] The move was seen as an attempt to extend U.S. dominance over the German government. The United States then offered a competing pipeline which it was expected that Germany should elect alternatively on U.S. terms.

Cultural relations

Karl May was a prolific German writer who specialized in writing Westerns. Although he visited America only once towards the end of his life, May provided Germany with a series of frontier novels, which provided Germans with an imaginary view of America.

Notable German-American architects, artist, musicians and writers include:

- Josef Albers, artist and educator

- Albert Bierstadt, known for his lavish, sweeping landscapes of the American West

- Philip K. Dick, writer

- Walter Gropius, architect

- Albert Kahn, architect

- Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, architect

- Paul Hindemith, composer

- Philip Johnson, architect

- Otto Klemperer, conductor

- Henry Miller, writer

- Les Paul, guitarist

- Carl Schurz, politician and writer

- Dr. Seuss, writer and illustrator

- Alfred Stieglitz, photographer

- Kurt Vonnegut, writer

German takes third place after Spanish and French among the foreign languages taught at American secondary schools, colleges and universities. Conversely, nearly half of the German population can speak English well.

A German-American Friendship Garden was built in Washington, DC, and stands as a symbol of the positive and co-operative relations between the United States and the Federal Republic of Germany. It is on the historic axis between the White House and the Washington Monument on the National Mall, the garden borders Constitution Avenue between 15th and 17th Streets, where an estimated seven million visitors pass each year. The garden features plants native to both Germany and the United States and provides seating and cooling fountains.[93] Commissioned to commemorate the 300th anniversary of German immigration to America, the garden was dedicated on November 15, 1988.[94]

Research and academia

Following the Nazi rise to power in 1933, and in particular the passing of the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service which removed opponents and persons with one Jewish grandparent from government positions (including academia), hundreds of physicists and other academics fled Germany and many came to the United States. James Franck and Albert Einstein were among the more notable scientists who ended up in the United States. Many of the physicists who fled were subsequently instrumental in the wartime Manhattan Project to develop the nuclear bomb. Following the World War II, some of these academics returned to Germany but many remained in the United States.[95][96]

After WWII and during the Cold War, Operation Paperclip was a secret United States Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency (JIOA) program in which more than 1,600 German scientists, engineers, and technicians (many of whom were formerly registered members of the Nazi Party and some of whom had leadership roles in the Nazi Party), including Wernher von Braun's rocket team, were recruited and brought to the United States for government employment from post-Nazi Germany.[97][98] Wernher von Braun, who built the German V-2 rockets, and his team of scientists came to the United States and were central in building the American space exploration program.[99]

Researchers at German and American universities run various exchange programs and projects, and focus on space exploration, the International Space Station, environmental technology, and medical science. Import cooperations are also in the fields of biochemistry, engineering, information and communication technologies and life sciences (networks through: Bacatec, DAAD). The United States and Germany signed a bilateral Agreement on Science and Technology Cooperation in February 2010.[100]

American cultural institutions in Germany

In the postwar era, a number of institutions, devoted to highlighting American culture and society in Germany, were established and are in existence today, especially in the south of Germany, the area of the former U.S. Occupied Zone. Today, they offer English courses as well as cultural programs.

Diplomatic missions

See also

- German in the United States

- German interest in the Caribbean

- History of German foreign policy

- US–EU relations

Notable organizations

References

- A.B. Faust, The German Element in the United States with Special Reference to Its Political, Moral, Social, and Educational Influence. (2 vol 1909), vol 1..

- Hans Wilhelm Gatzke, Germany and the United States, a "special Relationship?" (Harvard UP, 1980).

- Paul M. Kennedy, The Samoan Tangle: A Study in Anglo-German-American Relations 1878–1900 (University of Queensland Press, 2013).

- Holger H. Herwig, Politics of frustration: the United States in German naval planning, 1889–1941 (1976).

- Thomas Boghardt, The Zimmermann telegram: intelligence, diplomacy, and America's entry into World War I (Naval Institute Press, 2012).

- "United States of America". Federal Foreign Office. October 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-03-23. Retrieved 2016-04-02.

- "Germany and the United States: Reliable Allies: But Disagreement on Russia, Global Leadership and Trade," Pew Research Center: Global Attitudes and Trends 7 May, 2015

- "United States". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 31 January 2010.

- Numbers and Facts about Church Life in Germany 2016 Report. Evangelical Church of Germany. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- "America's Changing Religious Landscape". Pew Research Center. Pew Research Center. 2015-05-12. Retrieved September 4, 2016.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects".

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects".

- Smith, Claire M. (August 2010). "These are our Numbers: Civilian Americans Overseas and Voter Turnout" (PDF). OVF Research Newsletter. 2 (4): 4.

- "Ancestry 2000 : Census 2000 Brief" (PDF). Census.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-09-20. Retrieved 2016-08-27.

- Paul Leland Haworth, "Frederick the Great and the American Revolution" American Historical Review (1904) 9#3 pp. 460–478 open access in JSTOR

- Henry Mason Adams, Prussian-American Relations: 1775–1871 (1960).

- Sam A. Mustafa, Merchants and Migrations: Germans and Americans in Connection, 1776–1835 (2001)

- Manfred Jonas, The United States and Germany (1985) p 17

- Andrew Bonnell, "'Cheap and Nasty': German Goods, Socialism, and the 1876 Philadelphia World Fair." International Review of Social History 46#2 (2001): 207–226.

- Uwe Spiekermann, "Dangerous Meat? German-American Quarrels Over Pork And Beef, 1870–1900" Bulletin of the GHI vol 46 (Spring 2010) online

- Louis L. Snyder, "The American-German Pork Dispute, 1879-1891." Journal of Modern History 17.1 (1945): 16-28. online

- John L. Gignilliat, "Pigs, Politics, and Protection: The European Boycott of American Pork, 1879-1891," Agricultural History 35.1 (1961): 3-12. online

- Homer E. Socolofsky and Allan B. Spetter, The Presidency of Benjamin Harrison (1987). pp 131-36.

- Suellen Hoy, and Walter Nugent. "Public health or protectionism? The German-American pork war, 1880-1891." Bulletin of the History of Medicine 63#2 (1989): 198-224. online

- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (2009). The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars: A Political, Social, and Military History. ABC-CLIO. pp. 569–70. ISBN 9781851099511.

- Noah Andre Trudeau, "'An Appalling Calamity'--In the teeth of the Great Samoan Typhoon of 1889, a standoff between the German and US navies suddenly didn't matter." Naval History Magazine 25.2 (2011): 54-59.

- Homer E. Socolofsky and Allan B. Spetter, The Presidency of Benjamin Harrison (1987). pp. 114-16.

- George Herbert Ryden, The Foreign Policy of the United States in Relation to Samoa (1933).

- Walter LaFeber, The New Empire: An Interpretation of American Expansion, 1860–1898 (1963) pp 138-40, 323.

- Jonas, 60-64.

- Paul M. Kennedy, The Samoan Tangle: A Study in Anglo-German-American Relations 1878–1900 (2013).

- David H. Olivier (2004). German Naval Strategy, 1856–1888: Forerunners to Tirpitz. Routledge. p. 87. ISBN 9780203323236.

- Dirk Bönker (2012). Militarism in a Global Age: Naval Ambitions in Germany and the United States before World War I. Cornell U.P. p. 61. ISBN 978-0801464355.

- Lester D. Langley (1983). The Banana Wars: United States Intervention in the Caribbean, 1898–1934. p. 14. ISBN 9780842050470.

- Edmund Morris, "'A Matter Of Extreme Urgency' Theodore Roosevelt, Wilhelm II, and the Venezuela Crisis of 1902," Naval War College Review (2002) 55#2 pp 73–85

- Friedrich Katz, Secret War in Mexico: Europe, the United States and the Mexican Revolution (1981), pp. 50–64

- Edmund Morris, "A Matter of Extreme Urgency: Theodore Roosevelt." Wilhelm II, and the Venezuelan Crisis of 1902," Naval War College Review (2002) 55#2 pp 73-85.

- Harry Elmer Barnes, The Genesis of the World War (1925) pp. 590–591

- Jeanette Keith (2004). Rich Man's War, Poor Man's Fight: Race, Class, and Power in the Rural South during the First World War. U. of North Carolina Press. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-0-8078-7589-6.

- Thomas A. Bailey, A Diplomatic History of the American People (10th edition 1980) pp 563-95. online.

- Bailey, A Diplomatic History of the American People (1980) pp 596-613.

- Patrick O. Cohrs, "The First 'Real' Peace Settlements after the First World War: Britain, the United States and the Accords of London and Locarno, 1923–1925." Contemporary European History 12#1 (2003): 1–31.

- Jeffrey J. Matthews, Alanson B. Houghton: ambassador of the new era (2004) pp 48–49.

- Michael H. Kater, "The Jazz Experience in Weimar Germany." German History 6#2 (1988): 145+

- J. Bradford Robinson, Jazz reception in Weimar Germany: in search of a shimmy figure (1994).

- Thomas J. Saunders, Hollywood in Berlin: American Cinema and Weimar Germany (1994).

- Frank Costigliola, "The United States and the Reconstruction of Germany in the 1920s." Business History Review 50#4 (1976): 477–502.

- William C. McNeil, American Money and the Weimar Republic: Economics and Politics on the Eve of the Great Depression (1986).

- Mira Wilkins, Cosmopolitan finance in the 1920s: New York's emergence as an international financial centre (1999).

- Klaus Schwabe, "Anti-Americanism within the German Right, 1917–1933," Amerikastudien/American Studies (1976) 21#1 pp 89–108.

- Steven Casey, Cautious crusade: Franklin D. Roosevelt, American public opinion, and the war against Nazi Germany (2001).

- Robert Dallek (1995). Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy, 1932–1945. pp. 166, 171. ISBN 9780199826667.

- Maria Mazzenga, American religious responses to Kristallnacht (2009).

- Donald Fleming and Bernard Bailyn, eds. The intellectual migration: Europe and America, 1930–1960 (1968).

- Suzanne Shipley Toliver, "The Outsider As Outsider, German Intellectual Exiles In America After 1930." American Jewish Archives 38#1 (1986): 85–91. online

- Thomas Stritch, "After Forty Years: Notre Dame and The Review of Politics." The Review of Politics 40#4 (1978): 437–446.

- "Hollywood 'turned a blind eye' to the Nazis, says Kelsey Grammer". 2017-07-28.

- Helmore, Edward (2013-06-29). "Hollywood and Hitler: Did the studio bosses bow to Nazi wishes?". The Guardian.

- Roosevelt, Franklin Delano "On U.S. Involvement in the War in Europe" (speech) Washington, D.C. (March 15, 1941)

- Ruud van Dijk; et al. (2013). Encyclopedia of the Cold War. Routledge. pp. 414–15. ISBN 978-1135923112.

- Rainer Schnoor, "The Good and the Bad America: Perceptions of the United States in the GDR," in Detlef Junker, et al. eds. The United States and Germany in the Era of the Cold War, 1945–1968: A Handbook, Vol. 2: 1968–1990 (2004) p. 618, quotation on page 619.

- Wiegrefe, Klaus (24 November 2010). "Classified Papers Prove German Warnings to Bush". Spiegel Online. Translated by Josh Ward. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- Joschka Fischer interviewed by Gero von Boehm; originally broadcast on 3Sat in 2010; version with English subtitles on YouTube

- Gerrit-Jan Berendse, "German anti-Americanism in context." Journal of European Studies 33#3–4 (2003): 333–350.

- "Germany ends spy pact with US and UK after Snowden". BBC News. 2013-08-02. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- Philip J. Crowley (11 July 2014). "PJ Crowley: US-German relations have 'Groundhog Day'". News US & Canada. BBC.

- Oltermann, Phillip; Ackerman, Spencer (10 July 2014). "Germany asks top US intelligence official to leave country over spy row". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- Sullivan, Sean (8 July 2014). "Hillary Clinton 'sorry' that Merkel's phone was tapped". The Washington Post. Retrieved 11 July 2014.

- "Germany expels CIA official in US spy row". News/Europe. BBC. 10 July 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- "Sensible talks urged by Merkel to restore trust with US". Germany News.Net. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- Melanie Amann, Blome, Gebauer, Nelles, Repinski, Schindler & Weiland (July 22, 2014). "Keeping Spies Out: Germany Ratchets Up Counterintelligence Measures". Der Spiegel Online. Retrieved 23 July 2014.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Cillizza, Chris (29 May 2017). "How a single sentence from Angela Merkel showed what Trump means to the world". CNN. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- Müller, Peter (26 May 2017). "Trump in Brussels: 'The Germans Are Bad, Very Bad'". Der Spiegel Online. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- Tassilo Schneider, "Finding a new Heimat in the Wild West: Karl May and the German Western of the 1960s." Journal of Film and Video (1995): 50–66. in JSTOR

- Christopher Frayling, Spaghetti Westerns: Cowboys and Europeans from Karl May to Sergio Leone (2006)

- H. Glenn Penny, "Elusive authenticity: The quest for the authentic Indian in German public culture." Comparative Studies in Society and History 48#4 (2006): 798–819. online

- Robin Miller (2013-05-22). "Views of China and India Slide While UK's Ratings Climb". Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- "German Missions in the United States – Home" (PDF). Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- "Home – Indicators Database – Pew Research Center". Pew Research Center's Global Attitudes Project. 22 April 2010. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- Dan Diner, America in the eyes of the Germans: an essay on anti-Americanism (1996).

- Tuomas Forsberg, "German foreign policy and the war on Iraq: anti-Americanism, pacifism or emancipation?." Security Dialogue (2005) 36#2 pp: 213–231. online

- "Ami go Home," Economist Feb. 7, 2015, p 51

- "Jungkenn, Frederick Christian Arnold, freiherr von, 1732-1806". The University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 2006-12-05. Retrieved 2006-11-17.

- Choi, David (2018-06-30). "Trump was reportedly surprised by the number of US troops stationed in Germany and expressed interest in pulling some of them out". Business Insider. Retrieved 2019-03-08.

- "US Army's last tanks depart from Germany". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- Darnell, Michael S. (31 January 2014). "American tanks return to Europe after brief leave". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- "Trump Seeks Huge Premium From Allies Hosting U.S. Troops". 2019-03-07. Retrieved 2019-03-08.

- Gordon, Michael and Trainor, Bernard "Cobra II: The Inside Story of the Invasion and Occupation of Iraq" New York: 2006 ISBN 0-375-42262-5

- Wadhams, Nick; Jacobs, Jennifer (2019-03-07). "Trump Seeks Huge Premium From Allies Hosting U.S. Troops". Bloomberg. Retrieved 2019-03-08.

- Vittorio Valli, The American Economy from Roosevelt to Trump (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), passim.

- Sen. Cruz: ‘The Administration Needs to Immediately Begin Implementing These Sanctions’ on Nord Stream 2 Pipe-Laying Vessels, December 12, 2019, U.S. Senator Ted Cruz

- writer, staff (2019-12-17). "US Senate approves Nord Stream 2 Russia-Germany pipeline sanctions". Top Stories. Deutsche Welle. DW. Retrieved March 2, 2020.

The move by US lawmakers is part of a push to counter Russian influence in Europe, but European lawmakers have said the US should mind its own business.

- "Histories of the National Mall - German-American Friendship Garden". mallhistory.org.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-04-26. Retrieved 2018-10-29.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- The scientific exodus from Nazi Germany, Physics Today, 26 September 2018

- The Forgotten Women Scientists Who Fled the Holocaust for the United States, Lorraine Boissoneault, Smithsonianmag, 9 November 2017

- Jacobsen, Annie (2014). Operation Paperclip : the secret intelligence program to bring Nazi scientists to America. New York: Little, Brown and Company. p. Prologue, ix. ISBN 978-0-316-22105-4.

- "Joint Intelligence Objectives Agency". U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- Michael Neufeld (2008). Von Braun: Dreamer of Space, Engineer of War. Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 9780307389374.

- Dolan, Bridget M. (December 10, 2012). "Science and Technology Agreements as Tools for Science Diplomacy". Science & Diplomacy. 1 (4).

Bibliography

- Barclay, David E., and Elisabeth Glaser-Schmidt, eds. Transatlantic Images and Perceptions: Germany and America since 1776 (Cambridge UP, 1997).

- Bailey, Thomas A. A Diplomatic History of the American People (10th edition 1980) online free to borrow.

- Gatzke, Hans W. Germany and the United States: A "Special Relationship?" (Harvard UP, 1980); History of diplomatic relations.

- Jonas, Manfred. The United States and Germany: a diplomatic history (Cornell UP, 1985), a standard scholarly survey. excerpt

- Meyer, Heinz-Dieter. The design of the university: German, American, and “world class”. (Routledge, 2016).

- Trefousse, Hans Louis, ed. Germany and America: essays on problems of international relations and immigration (Brooklyn College Press, 1980), essays by scholars.

- Trommler, Frank and Joseph McVeigh, eds. America and the Germans: An Assessment of a Three-Hundred-Year History (2 vol. U of Pennsylvania Press, 1990) vol 2 online; detailed coverage in vol 2.

- Trommler, Frank, and Elliott Shore, eds. The German-American Encounter: conflict and cooperation between two cultures, 1800–2000 (2001), essays by cultural scholars.

Pre 1933

- Adam, Thomas and Ruth Gross, ed. Traveling Between Worlds: German-American Encounters (Texas A&M UP, 2006), primary sources.

- Adams, Henry Mason. Prussian-American Relations: 1775–1871 (1960).

- Bönker, Dirk (2012). Militarism in a Global Age: Naval Ambitions in Germany and the United States before World War I. Cornell U.P. ISBN 978-0801464355.

- Diehl, Carl. "Innocents abroad: American students in German universities, 1810–1870." History of Education Quarterly 16#3 (1976): 321–341. in JSTOR

- Dippel, Horst. Germany and the American Revolution, 1770–1800 (1977), Showed a deep intellectual impact on Germany of the American Revolution.

- Doerries, Reinhard R. Imperial Challenge: Ambassador Count Bernstorff and German-American Relations, 1908–1917 (1989).

- Faust, Albert Bernhardt. The German Element in the United States with Special Reference to Its Political, Moral, Social, and Educational Influence. 2 vol (1909). vol. 1, vol. 2

- Gazley, John Gerow. American Opinion of German Unification, 1848–1871 (1926). Noonan online

- Gienow-Hecht, Jessica C. E. "Trumpeting Down the Walls of Jericho: The Politics of Art, Music and Emotion in German-American Relations, 1870–1920," Journal of Social History (2003) 36#3

- Haworth, Paul Leland. "Frederick the Great and the American Revolution" American Historical Review (1904) 9#3 pp. 460–478 open access in JSTOR, Frederick hated England but kept Prussia neutral.

- Herwig, Holger H. Politics of frustration: the United States in German naval planning, 1889–1941 (1976).

- Junker, Detlef. The Manichaean Trap: American Perceptions of the German Empire, 1871–1945 (German Historical Institute, 1995).

- Keim, Jeannette. Forty years of German-American political relations (1919) online, Comprehensive analysis of major issues, including tariff, China, Monroe Doctrine.

- Leab, Daniel J. "Screen Images of the 'Other' in Wilhelmine Germany and the United States, 1890–1918." Film History 9#1 (1997): 49–70. in JSTOR

- Lingelbach, William E. "Saxon-American Relations, 1778–1828." American Historical Review 17#3 (1912): 517–539. online

- Link, Arthur S. Wilson: The Struggle for Neutrality, 1914–1915 (1960). vol 3 of his biography of Woodrow Wilson; vol 4 and 5 cover 1915–1917.

- Maurer, John H. "American naval concentration and the German battle fleet, 1900–1918." Journal of Strategic Studies 6#2 (1983): 147–181.

- Mitchell, Nancy. The danger of dreams: German and American imperialism in Latin America (1999).

- Mustafa, Sam A. Merchants and Migrations: Germans and Americans in Connection, 1776–1835 (2001).

- Pochmann, Henry A. German Culture in America: Philosophical and Literary Influences 1600–1900 (1957). 890pp; comprehensive review of German influence on Americans esp 19th century. online

- Schoonover, Thomas. Germany in Central America: Competitive Imperialism, 1821–1929(1998) online

- Schröder, Hans-Jürgen, ed. Confrontation and cooperation: Germany and the United States in the era of World War I, 1900–1924 (1993).

- Schwabe, Klaus "Anti-Americanism within the German Right, 1917–1933," Amerikastudien/American Studies (1976) 21#1 pp 89–108.

- Schwabe, Klaus. Woodrow Wilson, Revolutionary Germany, and Peacemaking, 1918–1919, University of North Carolina Press, 1985.

- Sides, Ashley. What Americans Said about Saxony, and what this Says about Them: Interpreting Travel Writings of the Ticknors and Other Privileged Americans, 1800—1850 (MA Thesis, University of Texas at Arlington, 2008). online

- Small, Melvin. "The United States and the German "Threat" to the Hemisphere, 1905–1914." The Americas 28#3 (1972): 252–270. Says there was no threat because Germany accepted the Monroe Doctrine.

- Trommler, Frank. "The Lusitania Effect: America's Mobilization against Germany in World War I." German Studies Review (2009): 241–266.

- Vagts, Alfred. Deutschland und die Vereinigten Staaten in der Weltpolitik (2 vols. (New York: Dornan, 1935), a major study that was never translated.

- Zacharasiewicz, Waldemar. Images of Germany in American literature (2007).

1933–1941

- Bell, Leland V. "The Failure of Nazism in America: The German American Bund, 1936–1941." Political Science Quarterly 85#4 (1970): 585–599. in JSTOR

- Dallek Robert. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy (Oxford University Press, 1979)

- Fischer, Klaus P. Hitler & America (2011) online

- Freidel, Frank. "FDR vs. Hitler: American Foreign Policy, 1933-1941" Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Vol. 99 (1987), pp. 25–43 online.

- Frye, Alton. Nazi Germany and the American Hemisphere, 1933–1941 (1967).

- Haag, John. "Gone With the Wind in Nazi Germany." Georgia Historical Quarterly 73#2 (1989): 278–304. in JSTOR

- Heilbut, Anthony. Exiled in Paradise: German Refugee Artists and Intellectuals in America from the 1930s to the Present (1983).

- Margolick, David. Beyond Glory: Joe Louis vs. Max Schmeling and a World on the Brink. (2005), world heavyweight boxing championship.

- Nagorski, Andrew. Hitlerland: American Eyewitnesses to the Nazi Rise to Power (2012).

- Norden, Margaret K. "American Editorial Response to the Rise of Adolf Hitler: A Preliminary Consideration." American Jewish Historical Quarterly 59#3 (1970): 290–301. in JSTOR

- Offner, Arnold A. American Appeasement: United States Foreign Policy and Germany, 1933–1938 (Harvard University Press, 1969) online edition

- Pederson, William D. ed. A Companion to Franklin D. Roosevelt (2011) online pp 636–52, FDR's policies

- Rosenbaum, Robert A. Waking to Danger: Americans and Nazi Germany, 1933–1941 (2010) online

- Schuler, Friedrich E. Mexico between Hitler and Roosevelt: Mexican foreign relations in the age of Lázaro Cárdenas, 1934–1940 (1999).

- Weinberg, Gerhard L. The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany (2 vols. (1980)

- Weinberg, Gerhard L. "Hitler's image of the United States." American Historical Review 69#4 (1964): 1006–1021. in JSTOR

After 1941

- Backer, John H. The Decision to Divide Germany: American Foreign Policy in Transition (1978)

- Bark, Dennis L. and David R. Gress. A History of West Germany Vol 1: From Shadow to Substance, 1945–1963 (1989); A History of West Germany Vol 2: Democracy and Its Discontents 1963–1988 (1989), the standard scholarly history in English

- Casey, Stephen, Cautious Crusade: Franklin D. Roosevelt, American Public Opinion, and the War against Nazi Germany (2004) online

- Junker, Detlef, et al. eds. The United States and Germany in the Era of the Cold War, 1945–1968: A Handbook, Vol. 1: 1945–1968; (2004) excerpt and text search; Vol. 2: 1968–1990 (2004) excerpt and text search, comprehensive coverage

- Gimbel John F. American Occupation of Germany (Stanford UP, 1968)

- Hanrieder Wolfram. West German Foreign Policy, 1949–1979 (Westview, 1980)

- Höhn, Maria H. GIs and Frèauleins: The German-American Encounter in 1950s West Germany (U of North Carolina Press, 2002)

- Immerfall, Stefan. Safeguarding German-American Relations in the New Century: Understanding and Accepting Mutual Differences (2006)

- Kuklick, Bruce. American Policy and the Division of Germany: The Clash with Russia over Reparations (Cornell University Press, 1972)

- Langenbacher, Eric, and Ruth Wittlinger. "The End of Memory? German-American Relations under Donald Trump." German Politics 27.2 (2018): 174-192.

- Ninkovich, Frank. Germany and the United States: The Transformation of the German Question since 1945 (1988)

- Nolan, Mary. "Anti-Americanism and Americanization in Germany." Politics & Society (2005) 33#1 pp 88–122.

- Pettersson, Lucas. "Changing images of the USA in German media discourse during four American presidencies." International Journal of Cultural Studies (2011) 14#1 pp 35–51.

- Pommerin, Reiner. The American Impact on Postwar Germany (Berghahn Books, 1995) online edition

- Smith Jean E. Lucius D. Clay (1990)

- Stephan, Alexander, ed. Americanization and anti-Americanism: the German encounter with American culture after 1945 (Berghahn Books, 2013).

- Szabo, Stephen F. "Different Approaches to Russia: The German–American–Russian Strategic Triangle." German Politics 27.2 (2018): 230-243, regarding the Cold War

Historiography

- Depkat, Volker. "Introduction: American History/ies in Germany: Assessments, Transformations, Perspectives." Amerikastudien/American Studies (2009): 337–343. in JSTOR

- Doerries, Reinhard R. "The Unknown Republic: American History at German Universities." Amerikastudien/American Studies (2005): 99–125. in JSTOR

- Gassert, Philipp. "Writing about the (American) past, thinking of the (German) present: The history of US foreign relations in Germany." Amerikastudien/American Studies (2009): 345–382. in JSTOR

- Gassert, Philipp. "The Study of U.S. History in Germany." European Contributions to American Studies (2007), Vol. 66, pp 117–132.

- Schröder, Hans-Jürgen. "Twentieth-Century German-American Relations: Historiography and Research Perspectives" in Frank Trommler, Joseph McVeigh eds., America and the Germans, Volume 2: An Assessment of a Three-Hundred Year History--The Relationship in the Twentieth Century (1985) online

External links

- U.S. Embassy and Consulates in Germany (in English and German)

- List of U.S. Embassy and Consulates in Germany (in English and German)

- German Missions in the United States (in English and German)

- List of German Embassy and Consulates General in the United States (in English and German)

- "A Guide to the United States’ History of Recognition, Diplomatic, and Consular Relations, by Country, since 1776: Germany". United States Department of State. Retrieved June 1, 2017.

- American Chamber of Commerce in Germany

- AICGS American Institute for Contemporary German Studies in Washington, D.C.

- American Council on Germany

- Atlantische Akademie Rheinland-Pfalz e.V.

- The Atlantic Times German reports on USA

- DAAD New York