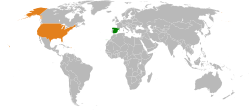

Spain–United States relations

The Spain–United States relations also referred to as the Spanish–American relations, refer to the diplomatic, social, economic and cultural relations between Spain and the United States of America.

| |

Spain |

United States |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Spanish Embassy, Washington, D.C. | Embassy of the United States, Madrid |

| Envoy | |

| Ambassador Santiago Cabanas | Ambassador Duke Buchan |

The groundwork for interstate relations between Spain and the US was laid by the colonization of parts of the Americas by the Hispanic Monarchy. The first settlement in Florida was Spanish, followed by more permanent, larger colonies in New Mexico, California, with a few elsewhere. The earliest Spanish settlements north of Mexico (known then as New Spain) were the results of the same forces that later led the British to come to that area. In order to add a Spanish dimension to the history of the US, the concept of "Spanish borderlands" (referring to the territories of the United States once claimed by Spain) was proposed in 20th-century historiography to nuance the traditional Anglo-centric vision.[1]

Spain, that provided support to the Thirteen Colonies during the American Revolutionary War against the Kingdom of Great Britain, tacitly recognised the independence of the United States in 1783. The purchase of the Spanish Florida by the US was made effective in 1821. US efforts to buy Cuba in the 1850s failed. When Cuba revolted in the late 19th century American opinion became hostile to Spanish brutality. The Spanish–American War erupted in 1898. The Spanish defeat in the conflict entailed the loss of the last Spanish colonies in the Americas and Southeast Asia, including Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines.

With the onset of the Cold War the US threw a lifeline to the Francoist dictatorship (rather ostracised immediately after World War II), also reaching a deal with Spain to set several military bases in the country in 1953,[2] of which two of them (Morón and Rota) still are jointly operated by the US.

History of Spanish–American relations has been defined as one of "love and hate".[3]

Spain and the American Revolution

Spain declared war on Britain as an ally of France, and provided supplies and munitions to the American forces. However Spain was not an ally of the Patriots. It was reluctant to recognize the independence of the United States, because it distrusted revolutionaries. Historian Thomas A. Bailey says of Spain:

- Although she was attracted by the prospect of a war [against England] for restitution and revenge, she was repelled by the specter of an independent and powerful American republic. Such a new state might reach over the Alleghenies into the Mississippi Valley and grasp territory that Spain wanted for herself.[4]

Among the most notable Spaniards that fought during the American Revolutionary War were Bernardo de Gálvez y Madrid, Count of Gálvez, who defeated the British colonial forces at Manchac, Baton Rouge, and Natchez in 1779, freeing the lower Mississippi Valley of British forces and relieved the threat to the capital of Louisiana, New Orleans. In 1780, he recaptured Mobile and in 1781 took by land and by sea Pensacola, leaving the British with no bases in the Gulf of Mexico. In recognition for his actions to the American cause, George Washington took him to his right in the parade of July 4 and the American Congress cited Gálvez for his aid during the Revolution.

Floridablanca instructed the Count of Aranda to sign a Treaty with the United States on 17 March 1783, thus making Spain tacitly recognise then the independence of the US.[5]

Another notable contributor was Don Diego de Gardoqui, who was appointed as Spain's first ambassador to the United States of America in 1784. Gardoqui became well acquainted with George Washington, and also marched in the newly elected President Washington's inaugural parade. King Charles III of Spain continued communications with Washington, sending him gifts such as livestock from Spain that Washington had requested for his farm at Mount Vernon.[6]

Spain and the United States in the late 18th century

The United States' first ambassador to Spain was John Jay (but was not formally received at court). Jay's successor, William Carmichael, married a Spanish woman and is buried in the Catholic cemetery in Madrid. Some friendly ties were established: George Washington had established the American mule-raising industry with high-quality large donkeys sent to him by the King of Spain (as well as Lafayette).[7]

Spain fought the British as an ally of France during the Revolutionary War, but it distrusted republicanism and was not officially an ally of the United States. After the war, the main relationships dealt with trade, with access to the Mississippi River, and with Spanish maneuvers with Native Americans to block American expansion.[8] Spain controlled the territories of Florida and Louisiana, positioned to the south and west of the United States. Americans had long recognized the importance of navigation rights on the Mississippi River, as it was the only realistic outlet for many settlers in the trans-Appalachian lands to ship their products to other markets, including the Eastern Seaboard of the United States.[9] Despite having fought a common enemy in the Revolutionary War, Spain saw U.S. expansionism as a threat to its empire. Seeking to stop the American settlement of the Old Southwest, Spain denied the U.S. navigation rights on the Mississippi River, provided arms to Native Americans, and recruited friendly American settlers to the sparsely populated territories of Florida and Louisiana.[10] Additionally, Spain disputed the Southern and Western borders of the United States. The most important border dispute centered on the border between Georgia and West Florida, as Spain and the United States both claimed parts of present-day Alabama and Mississippi. Spain paid cash to American General James Wilkinson for a plot to make much of the region secede, but nothing came of it.[11] Meanwhile, Spain worked on the goal of stopping American expansion by setting up an Indian buffer state in the South. They worked with Alexander McGillivray (1750-1793), who was born to a Scottish trader and his French-Indian wife, and he had become a leader of the Creek tribe as well as an agent for British merchants. In 1784-1785, treaties were signed with Creeks, the Chickasaws, and the Choctaws to make peace among themselves, and ally with Spain. While the Indian leaders were receptive, Yankee merchants were much better suppliers of necessities than Spain, and the pan-Indian coalition proved unstable.[12][13][14]

On the positive side, Spanish merchants welcomed trade with the new nation, which had been impossible when it was a British colony. it therefore encourage the United States to set up consulates in Spain's New World colonies[15] American merchants and Eastern cities likewise wanted to open trade with the Spanish colonies which had been forbidden before 1775.[16] A new line of commerce involved American merchants importing goods from Britain, and then reselling them to the Spanish colonies.[17]

John Jay negotiated a treaty with Spain to resolve these disputes and expand commerce. Spain also tried direct diplomacy offering access to the Spanish market, but the cost of closing the Mississippi to Western farmers for 25 years and blocking southern expansionists. The resulting Jay–Gardoqui Treaty was rejected by coalition of Southerners led by James Madison and James Monroe of Virginia, who complained that it hurt their people and instead favored Northeastern commercial interests. the treaty was defeated.[18][19]

Pinckney's Treaty, also known as the Treaty of San Lorenzo or the Treaty of Madrid, was signed in San Lorenzo de El Escorial on October 27, 1795 and established intentions of friendship between the United States and Spain. It also defined the boundaries of the United States with the Spanish colonies and guaranteed the United States navigation rights on the Mississippi River.

The early nineteenth century

Spanish–American relations suffered during the 19th century, as both countries competed for territory and concessions in the New World. "Culturally, they misunderstood and distrusted each other", James W. Cortada has written. "Political conflicts and cultural differences colored relations between the two nations throughout the nineteenth century, creating a tradition of conflict of a generally unfriendly nature. By 1855, a heritage of problems, hostile images, and suspicions existed which profoundly influenced their relations."[20]

During the Peninsular War, when Spain had two rival Kings – the overthrown Bourbon Fernando VII and Napoleon's brother, Joseph Bonaparte, enthroned as José I of Spain – the United States officially maintained a neutral position between them. Ambassador Luis de Onís who arrived in New York in 1809, representing Fernando VII's government, was refused an audience to present his credentials to President Madison. He was only recognized officially by the US government in 1815, following Napoleon's defeat – though in the meantime he had established himself in Philadelphia and unofficially conducted extensive diplomatic activity.

The two countries found themselves on opposite sides during the War of 1812. By 1812 the continued existence of Spanish colonies east of the Mississippi River caused resentment in the United States. The Spanish arming of black militia alarmed slaveholders in the southern states of the US.[21] With clandestine support from Washington, American settlers in the Floridas revolted against Spanish rule.[21] Spain lost its West Florida colony.[21] Between 1806 and 1821, the area known as the "Sabine Free State" was an area between Spanish Texas and the United States that both sides agreed to maintain as neutral due to disputes over the area.

The Adams–Onís Treaty between the two countries was signed in 1819. The treaty was the result of increasing tensions between the U.S. and Spain regarding territorial rights at a time of weakened Spanish power in the New World. In addition to granting Florida to the United States, the treaty settled a boundary dispute along the Sabine River in Texas and firmly established the boundary of U.S. territory and claims through the Rocky Mountains and west to the Pacific Ocean in exchange for the U.S. paying residents' claims against the Spanish government up to a total of $5,000,000 and relinquishing its own claims on parts of Texas west of the Sabine River and other Spanish areas.

By the mid-1820s, Spaniards believed that the United States wanted to control the entire New World at Spain's expense, considering the independence movements in Latin America as proof of this.[22] In 1821, a Spaniard wrote that Americans "consider themselves superior to all the nations of Europe."[23] In the United States, Spain was viewed as permanently condemned by the Black Legend, and as a backward, crude, and despotic country that opposed the Monroe Doctrine and Manifest Destiny.[24] Nevertheless, travel literature on Spain sold well in the US, and the writings of Washington Irving, who had served as U.S. Minister to Spain, generated some friendly spirit in the United States towards Spain.[24]

Mid-nineteenth century

Tensions continued throughout the 19th century. Queen Isabella II, who reigned from 1833 to 1868, became a dominant figure in Spanish-American relations. In 1839 she became involved in the Amistad affair, over the fate of the schooner La Amistad and the 53 slaves she carried. Isabella was one of several claimants to their ownership, and even after its resolution in 1841, following a U.S. Supreme Court decision, the Spanish government continued to press for compensation. She involved her country in the Chincha Islands War (1864–66), which pitted Spain against her former possessions of Peru and Chile. The American Minister to Chile, Hugh Judson Kilpatrick, was involved in an attempt to arbitrate between the combatants of the Chincha Islands War. The attempt failed, and Kilpatrick asked the American naval commander Commander Rodgers to defend the port and attack the Spanish fleet. Admiral Casto Méndez Núñez famously responded with, "I will be forced to sink [the US ships], because even if I have one ship left I will proceed with the bombardment. Spain, the Queen and I prefer honor without ships than ships without honor." ("España prefiere honra sin barcos a barcos sin honra".) During the Chincha Islands War, Spanish Admiral Pareja imposed a blockade of Chile's main ports. The blockade of the port of Valparaíso, however, caused such great economic damage to Chilean and foreign interests, that the neutral naval warships of the United States and Great Britain lodged a formal protest.

During the mid-nineteenth century, one American diplomat declared:

You must treat Spain as you would a pretty woman with a bad temper. Firm and constant and unyielding in your purpose, but flexible and always flattering in form – watching her moods – taking advantages of her prejudices and passions to modify her conduct towards you... logic and sound policy will not guide her unless you take good care of the region of her sentiments first.

— Horatio J. Perry[25]

Cuba

But it was the issue of Cuba that dominated relations between Spain and the United States during this period. At the same time that the United States wished to expand its trade and investments in Cuba during this period, Spanish officials enforced a series of commercial regulations designed to discourage trade relations between Cuba and the U.S. Spain believed that American economic encroachment would result in physical annexation of the island; the kingdom fashioned its colonial policies accordingly.[26]

In a letter to Hugh Nelson, U.S. Minister to Spain, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams described the likelihood of U.S. "annexation of Cuba" within half a century despite obstacles: "But there are laws of political as well as of physical gravitation; and if an apple severed by the tempest from its native tree cannot choose but fall to the ground, Cuba, forcibly disjoined from its own unnatural connection with Spain, and incapable of self support, can gravitate only towards the North American Union, which by the same law of nature cannot cast her off from its bosom."[27]

In 1850, John A. Quitman, Governor of Mississippi, was approached by the filibuster Narciso López to lead his filibuster expedition of 1850 to Cuba. Quitman turned down the offer because of his desire to serve out his term as Governor, but did offer assistance to López in obtaining men and material for the expedition.

In 1854 a secret proposal known as the Ostend Manifesto was devised by U.S. diplomats to acquire Cuba from Spain for $130 million. The manifesto was rejected due to objections from anti-slavery campaigners when the plans became public.[28] When President Buchanan addressed Congress on December 6, 1858, he listed several complaints against Spain, which included the treatment of Americans in Cuba, lack of direct diplomatic communication with the captain general of Cuba, maritime incidents, and commercial barriers to the Cuban market. "The truth is that Cuba", Buchanan stated, "in its existing colonial condition, is a constant source of injury and annoyance to the American people." Buchanan went on to hint that the US may be forced to purchase Cuba and stated that Cuba's value to Spain "is comparatively unimportant." The speech shocked Spanish officials.[29]

Santo Domingo

Another source of conflict and rivalry was Santo Domingo (the Dominican Republic), an independent republic that Spain annexed at the request of Pedro Santana in 1861. The U.S. and Spain had competed with one another for influence in Hispaniola in the 1850s and 1860s; the U.S. was worried about a possible military expansion by Spain in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico (which would make it harder to acquire Cuba).[30]

Spain and the American Civil War

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, the Union was concerned about possible European aid to the Confederacy as well as official diplomatic recognition of the breakaway republic. In response to possible intervention from Spain, President Lincoln sent Carl Schurz, who he felt was able and energetic, as minister to Spain; Schurz's chief duty would be to block Spanish recognition of, and aid to, the Confederacy. Part of the Union strategy in Spain was to remind the Spanish court that it had been Southerners, now Confederates, who had pressed for annexation of Cuba.[31] Schurz was successful in his efforts; Spain officially declared neutrality on June 17, 1861.[31] However, since neither the Union nor the Confederacy would sign a formal treaty guaranteeing that Cuba would never be threatened, Madrid remained convinced that American imperialism would resume as soon as the Civil War had ended.[32]

Spanish–American War

The Spanish–American War began in April 1898. Hostilities halted in August of that year, and the Treaty of Paris was signed in December.

In June 1897, President William McKinley had appointed Stewart L. Woodford to the post of Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to Spain, in a last attempt to convince the Spanish government to sell its colonies. Spain refused and severed diplomatic relations with the U.S. on April 21, 1898.

The War was the first conflict in which military action was precipitated by media involvement. The war grew out of U.S. interest in a fight for revolution between the Spanish military and citizens of their Cuban colony. American yellow press fanned the flames of interest in the war by fabricating atrocities during the Cuban War of Independence, in order to justify intervention in a number of Spanish colonies worldwide, like Puerto Rico, the Philippines, Guam and the Caroline Islands.[33]

Many stories were either elaborated, misrepresented or completely fabricated by journalists to enhance their dramatic effect. Theodore Roosevelt, who was the Assistant Secretary of the Navy at this time, wanted to use the conflict both to help heal the wounds still fresh from the American Civil War, and to increase the strength of the US Navy, while simultaneously establishing America as a presence on the world stage. Roosevelt put pressure on the United States Congress to come to the aid of the Cuban people. He emphasized Cuban weakness and femininity to justify America's military intervention.

Riots in Havana by pro-Spanish "Voluntarios" gave the United States the perfect excuse to send in the warship USS Maine. After the unexplained explosion of the USS Maine, tension among the American people was raised by the anti-Spanish campaign that accused Spain of extensive atrocities, agitating American public opinion.

The war ended after decisive naval victories for the United States in the Philippines and Cuba, only 109 days after the outbreak of war. The Treaty of Paris, which ended the conflict, gave the United States ownership of the former Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico, the Philippines and Guam.

Spain had appealed to the common heritage shared by her and the Cubans. On March 5, 1898, Ramón Blanco y Erenas, Spanish governor of Cuba, proposed to Máximo Gómez that the Cuban generalissimo and troops join him and the Spanish army in repelling the United States in the face of the Spanish–American War. Blanco appealed to the shared heritage of the Cubans and Spanish, and promised the island autonomy if the Cubans would help fight the Americans. Blanco had declared: "As Spaniards and Cubans we find ourselves opposed to foreigners of a different race, who are of a grasping nature. ... The supreme moment has come in which we should forget past differences and, with Spaniards and Cubans united for the sake of their own defense, repel the invader. Spain will not forget the noble help of its Cuban sons, and once the foreign enemy is expelled from the island, she will, like an affectionate mother, embrace in her arms a new daughter amongst the nations of the New World, who speaks the same language, practices the same faith, and feels the same noble Spanish blood run through her veins."[34] Gómez refused to adhere to Blanco's plan.[35]

In Spain, a new cultural wave called the Generation of 1898 originated as a response to the trauma caused by this disastrous war, marking a renaissance of the Spanish culture.

Spanish–American relations: 1898–1936

In spite of having been proven false, many of the lies and negative connotations against Spain and the Spanish people, product of the propaganda of the Spanish–American War, lingered for a long time after the end of the war itself, and contributed largely to a new recreation of the myth of the Black Legend against Spain.

The war also left a residue of anti-American sentiment in Spain,[36] whose citizens felt a sense of betrayal by the very country they helped to obtain the Independence against the British. Many historians and journalists pointed out also the needless nature of this war, because up to that time, relations between Spain and the United States had always enjoyed very amiable conditions, with both countries resolving their differences with mutual agreements that benefited both sides, such as with the sale of Florida by terms of the Treaty of Amity.

Nonetheless, in the post-war period, Spain enhanced its trading position by developing closer commercial ties with the United States.[36] The two countries signed a series of trade agreements in 1902, 1906, and 1910.[36] These trade agreements led to an increased exchange of manufactured goods and agricultural products.[36] American tourists began to come to Spain during this time.[36]

.jpg)

Spain, under Alfonso XIII, remained neutral during the First World War, and the war greatly benefited Spanish industry and exports.[37] At the same time, Spain did intern a small German force in Spanish Guinea in November 1915 and also worked to ease the suffering of prisoners of war.[37] Spain was a founding member of the League of Nations in 1920 (but withdrew in May 1939).

During the 1920s and 1930s, the United States Army developed a number of color-coded war plans to outline potential U.S. strategies for a variety of hypothetical war scenarios. All of these plans were officially withdrawn in 1939. "War Plan Olive" was for Spain. The two countries were engaged in a tariff war after the Fordney–McCumber Tariff was passed in 1922 by the United States; Spain raised tariffs on American goods by 40%.[38] In 1921, a "Student on tariffs" had warned against the Fordney Bill, declaring in the New York Times that "it should be remembered that the Spanish are a conservative people. They are wedded to their ways and much inertia must be overcome before they will adopt machinery and devices such as are largely exported from the United States. If the price of modern machinery, not manufactured in Spain, is increased exorbitantly by high customs duties, the tendency of the Spanish will be simply to do without it, and it must not be imagined that they will purchase it anyhow because it has to be had from somewhere."[39]

In 1928, Calvin Coolidge greeted King Alfonso on the telephone; it was the first use by the president of a new Transatlantic Telephone Line with Spain.[40]

Culturally, during the 1920s, Spanish feelings towards the United States remained ambivalent. A New York Times article dated June 3, 1921, called "How Spain Views U.S.", quotes a Spanish newspaper (El Sol) as declaring that the "United States is a young, formidable and healthy nation." The article in El Sol also expressed the opinion that "the United States is a nation of realities, declaring that Spain in its foreign policy does not possess that quality." The Spanish newspaper, in discussing the relations between Spain and the U.S., also argued "that the problem of acquiring a predominant position in the South American republics should be vigorously studied by Spain."[41]

In 1921, Luis Araquistáin had written a book called El Peligro Yanqui ("The Yankee Peril"), in which he condemned American nationalism, mechanization, anti-socialism ("socialism is a social heresy there") and architecture, finding particular fault with the country's skyscrapers, which he felt diminished individuality and increased anonymity. He called the United States "a colossal child: all appetite ..."[42] Nevertheless, America exercised an obvious fascination on Spanish writers during the 1920s. While in the United States, Federico García Lorca had stayed, among other places, in New York City, where he studied briefly at Columbia University School of General Studies. His collection of poems Poeta en Nueva York explores his alienation and isolation through some graphically experimental poetic techniques. Coney Island horrified and fascinated Lorca at the same time. "The disgust and anatagonism it aroused in him", writes C. Brian Morris, "suffuse two lines which he expunged from his first draft of 'Oda a Walt Whitman': "Brooklyn filled with daggers / and Coney Island with phalli."[43]

The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939

When the Spanish Civil War erupted in 1936, the United States remained neutral and banned arms sales to either side. This was in line with both American neutrality policies, and with a Europe-wide agreement to not sell arms for use in the Spanish war lest it escalate into a world war. Congress endorsed the embargo by a near-unanimous vote. Only armaments were embargoed; American companies could sell oil and supplies to both sides. Roosevelt quietly favored the left-wing Republican (or "Loyalist") government, but intense pressure by American Catholics forced him to maintain a policy of neutrality. The Catholics were outraged by the systematic torture, rape and execution of priests, bishops, and nuns by anarchist elements of the Loyalist coalition. This successful pressure on Roosevelt was one of the handful of foreign policy successes notched by Catholic pressures on the White House in the 20th century.[44] Germany and Italy provided munitions, and air support, and troops to the Nationalists, led by Francisco Franco. The Soviet Union provided aid to the Loyalist government, and mobilized thousands of volunteers to fight, including several hundred from the United States in the Abraham Lincoln Battalion. All along the Spanish military forces supported the nationalists, and they steadily pushed the government forces back. By 1938, however, Roosevelt was planning to secretly send American warplanes through France to the desperate Loyalists. His senior diplomats warned that this would worsen the European crisis, so Roosevelt desisted.[45]

The Nationalists, led by Francisco Franco, received important support from some elements of American business. The American-owned Vacuum Oil Company in Tangier, for example, refused to sell to Republican ships and at the outbreak of the war, the Texas Oil Company rerouted oil tankers headed for the Republic to the Nationalist-controlled port of Tenerife,[46] and supplied tons of gasoline on credit to Franco until the war's end. American automakers Ford, Studebaker, and General Motors provided a total of 12,000 trucks to the Nationalists. After the war was over, José Maria Doussinague, who was at the time undersecretary at the Spanish Foreign Ministry, said, "without American petroleum and American trucks, and American credit, we could never have won the Civil War."[46] While working for the North American Newspaper Alliance (NANA), American novelist Ernest Hemingway and the war correspondent Martha Gellhorn tried to draw a connection between Adolf Hitler and Franco, even though both leaders mutually disliked one another, and Franco tended to manipulate Hitler for his own benefit during the war; Franco never turned over the Spanish Jews to Nazi Germany as requested, and when the Blue Division was dispatched to help the Germans, it was forbidden to fight against the Allies, and was limited only to fighting Soviet Russia. Although not supported officially, many American volunteers such as the Abraham Lincoln Battalion fought for the Republicans, as well as American anarchists making up the Sacco and Vanzetti Century of the Durruti Column.[47] American poets like Alvah Bessie, William Lindsay Gresham, James Neugass, and Edwin Rolfe were members of the International Brigades. Wallace Stevens, Langston Hughes, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Randall Jarrell, and Philip Levine also wrote poetic responses to the Spanish Civil War.[48] Kenneth Porter's poetry speaks of America's "insulation by ocean and 2,000 miles of complacency", and describes the American "men from the wheatfields / Spain was a furious sun which drew them along paths of light."[49]

During and after the Spanish Civil War, members of the brigade were viewed as supporters of the Soviet Union. Through the period of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, Communist Lincoln Brigade veterans joined with the American Peace Mobilization in protesting U.S. support for Britain against Nazi Germany.[50] During and following World War II, particularly at the height of the Second Red Scare, the U.S. government considered former members of the brigade to be security risks. In fact, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover persuaded President Franklin D. Roosevelt to ensure that former ALB members fighting in U.S. Forces in World War II not be considered for commissioning as officers, or to have any type of positive distinction conferred upon them.

World War II

Spain sympathized with the Axis powers during World War II. While officially non-belligerent until 1943, General Franco's government sold considerable material, especially tungsten, to Germany, and purchased machinery. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of exiled Leftist Republicans, contributed to the Allied cause. Thousands also volunteered in Blue Division, which fought for the Axis. As Germany weakened, Spain cut back its sales.

From 1942 to 1945, American historian Carlton J. H. Hayes served as President Roosevelt's ambassador to Spain. He was attacked at the time from the left for being overly friendly with Franco, but it has been generally held that he played a vital role in preventing Franco from siding with the Axis powers during the war.[51] Historian Andrew N. Buchanan argues that Hayes made Spain into "Washington's 'silent ally.'" [52]

Spain unknowingly played an important role in the invasion of Sicily through Operation Mincemeat, where a corpse with the fabricated identity of a British intelligence officer was purposefully washed ashore with false allied documents hinting to an invasion of Sardinia. Spanish officials handed these papers over to German intelligence officials, who in turn placed an emphasis on troop placement and defense in Sardinia rather than the true target of allied invasion, Sicily.

Historian Emmet Kennedy rejects allegations that Hayes was an admirer of Franco. Instead he was "a tough critic of the caudillo's 'fascism'". Hayes played a central role in rescuing 40,000 refugees – French, British, Jews and others from Hitler. He helped them cross the Pyrenees into Spain and onward to North Africa. He made Spain "a haven from Hitler." In retirement, Kennedy finds, Hayes advocated patient diplomacy, rather than ostracism or subversion of Franco's Spain. That was the policy adopted by President Eisenhower as Franco led Spain into an alliance with the U.S. in the 1950s.[53] The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee operated openly in Barcelona.[54][55]

The United States and Franco

With the end of World War II, Spain suffered from the economic consequences of its isolation from the international community. Spain was blocked from joining the United Nations, primarily by the large Communist element in France. By contrast the American officials 1946 "praised the favorable 'transformation' that was occurring in US-Spanish relations."[56] United States needed Spain as a strategically located ally in the Cold War against the Soviet Union after 1947.

President Harry S. Truman was a very strong opponent of Franco, calling him an evil anti-Protestant dictator comparable to Hitler and Mussolini. Truman withdrew the American ambassador (but diplomatic relations were not formally broken), kept Spain out of the UN, and rejected any Marshall Plan financial aid to Spain. However, as the Cold War escalated, support for Spain sharply increased in the Pentagon, Congress, the business community and other influential elements especially Catholics and cotton growers. Liberal opposition to Spain faded after the Henry A. Wallace element broke with the Democratic Party in 1948; the CIO dropped its strong opposition and became passive on the issue. As Secretary of State Dean Acheson increased his pressure on Truman, the president, stood alone in his administration as his own top appointees wanted to normalize relations. When China entered the Korean War and pushed American forces back, the argument for allies became irresistible. Admitting that he was "overruled and worn down," Truman relented and sent an ambassador and made loans available in late 1950.[57]

Trade relations improved. Exports to Spain rose from $43 million in 1946 to $57 million in 1952; imports to the US rose from $48 million to $63 million.[58] A formal alliance commenced with the signing of the Pact of Madrid in 1953. Spain was then admitted to the United Nations in 1955. American poet James Wright wrote of Eisenhower's visit: "Franco stands in a shining circle of police. / His arms open in welcome. / He promises all dark things will be hunted down."[49]

In the context of the Arab–Israeli conflict, Spain played the role of mediator between the Arab countries (such as the Nasser's United Arab Republic) and the United States. The Spanish diplomacy, led by Fernando María Castiella, showed disregard for what Spain regarded as the unconditional US support to the State of Israel and for the American attempt to sow discord among the Arab nations.[59]

Between 1969 and 1977, the period comprising the mandates of Henry Kissinger as National Security advisor and as Secretary of State of the US during the Nixon and Ford administrations, the US foreign policy towards Spain was driven by the American need to guarantee access to the military bases on Spanish soil.[60] Military facilities of the United States in Spain built during the Franco era include Naval Station Rota and Morón Air Base, and an important facility existed at Torrejón de Ardoz. Torrejón passed under Spanish control in 1988. Rota has been in use since the 1950s. Crucial to Cold War strategy, the base did have nuclear weapons stationed on it for some time, and at its peak size, in the early 1980s, was home to 16,000 sailors and their families. The presence of these bases in Spain was much unpopular among the Spanish people (according to a 1976 poll by Louis Harris International, only 1 out of 10 Spaniards supported the American presence in the country);[61] there were occasional protests against them, including a demonstration during President Reagan's 1985 visit to Spain.[36]

During the agony of the Franco dictatorship and later Transition, Kissinger, related to the realist school, would support the notion of an orderly regime change for Spain, thus not risking access to the bases as well as facilitating the full incorporation of Spain to the Western sphere, putting nearly all the eggs on the basket of Juan Carlos I.[62]

Post-Franco era

President Richard Nixon toasted Franco[63] and after Franco's 1975 death, stated: "General Franco was a loyal friend and ally of the United States.[64]"

In 1976, Spain and the United States signed a Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation (Tratado de Amistad y Cooperación), coinciding with the new political system in Spain, which became a constitutional monarchy under Juan Carlos I, with Carlos Arias Navarro as prime minister.[3] Juan Carlos had already established friendly ties with the United States. As prince, he had been a guest of Nixon on January 26, 1971.[65] Nixon toasted the visit with these words:

And we are reminded, as I pointed out this morning, of the fact that the United States and all the New World owe so much to Spain, the great courageous explorers who found the New World and who explored it, and that we owe far more than that in culture and language and the other areas with which we are familiar. And all of us who have visited Spain, too, know that it is a magnificent country to visit because of the places of historical interest there, because, also, of the immense and unique warmth and hospitality which characterizes the Spanish people.

— Richard Nixon, [65]

In 1987, Juan Carlos I became the first King of Spain to visit the former Spanish possession of Puerto Rico. In the same year, Juan Carlos dedicated a statue of Charles III of Spain by Federico Coullaut-Valera in Olvera Street, Los Angeles. Charles had ordered the founding of the town that became Los Angeles.[66]

An Agreement on Defense Cooperation was signed by the two countries in 1989 (it was revised in 2003), in which Spain authorized the United States to use certain facilities at Spanish military installations.[67] On June 7, 1989, an agreement on cultural and educational cooperation was signed.[67]

Iraq War

Prime Minister José María Aznar actively supported U.S. President George W. Bush and UK Prime Minister Tony Blair in the War on Terrorism. Aznar met with Bush in a private meeting before 2003 invasion of Iraq to discuss the situation of in the United Nations Security Council. The Spanish newspaper El País leaked a partial transcript of the meeting. Aznar actively encouraged and supported the Bush administration's foreign policy and the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, and was one of the signatories of The letter of the eight defending it on the basis of secret intelligence allegedly containing evidence of the Iraqi government's nuclear proliferation. The majority of the Spanish population, including some members of Aznar's Partido Popular, were against the war.

After the Spanish general election in 2004, in which the Spanish socialists received more votes than expected as a result, besides other issues, of the government's handling of the 2004 Madrid train bombings, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero succeeded Aznar as Prime Minister. Before being elected, Zapatero had opposed the American policy in regard to Iraq pursued by Aznar. During the electoral campaign Zapatero had promised to withdraw the troops if control in Iraq was not passed to the United Nations after June 30 (the ending date of the initial Spanish military agreement with the multinational coalition that had overthrown Saddam Hussein). On April 19, 2004 Zapatero announced the withdrawal of the 1300 Spanish troops in Iraq.[68]

The decision aroused international support worldwide, though the American Government claimed that the terrorists could perceive it as "a victory obtained due to 11 March 2004 Madrid train bombings". John Kerry, then Democratic party candidate for the American Presidency, asked Zapatero not to withdraw the Spanish soldiers. Some months after withdrawing the troops, the Zapatero government agreed to increase the number of Spanish soldiers in Afghanistan and to send troops to Haiti to show the Spanish Government's willingness to spend resources on international missions approved by the UN.

Bush and Zapatero, 2004–2008

The withdrawal caused a four-year downturn in relations between Washington and Madrid.[69] A further rift was caused by the fact that Zapatero openly supported Democratic challenger John Kerry on the eve of the U.S. elections in 2004.[69] Zapatero was not invited to the White House until the last months of the Bush administration, nor was Bush invited to La Moncloa.[69] Aznar had visited Washington several times, becoming the first Spanish prime minister to address a joint meeting of Congress, in February 2004.[70] Bush's fellow Republican, and candidate for the 2008 U.S. presidential election, John McCain, refused to commit to a meeting with Zapatero were he to be elected.[71]

Spain under Zapatero turned its focus to Europe from the United States, pursuing a middle road in dealing with tensions between Western powers and Islamic populations.[70] In a May 2007 interview with El País, Daniel Fried, Assistant Secretary for European and Eurasian Affairs, commenting on the overall relationship between Spain and the United States, stated: "We work together very well on some issues. I think the Spanish–American relationship can develop more. I think some Spanish officials are knowledgeable and very skilled professionals and we work with them very well. I would like to see Spain active in the world, working through NATO, active in Afghanistan. You're doing a lot in the Middle East because Moratinos knows a lot about it. But Spain is a big country and your economy is huge. I think Spain can be a force for security and peace and freedom in the world. I believe that Spain has that potential, and that's how I would like to see Spanish–American relations developing."[72]

Cuba

In 2007, Condoleezza Rice criticized Spain for not doing more to support dissidents in communist Cuba.[69] American officials were irked by the fact that Miguel Ángel Moratinos, Minister of Foreign Affairs, chose not to meet with Cuban dissidents during a visit to the United States in April 2007.[70] "There is no secret that we have had differences with Spain on a number of issues, but we have also had very good cooperation with Spain on a number of issues", Rice remarked.[69] Moratinos defended his decision, believing it better to engage with the Cuban regime than by isolating it. "The U.S. established its embargo", he remarked. "We don't agree with it but we respect it. What we hope is that they respect our policy", Moratinos remarked. "What Spain is not prepared to do is be absent from Cuba. And what the U.S. has to understand is that, given they have no relations with Cuba, they should trust in a faithful, solid ally like Spain."[70] On the relationship between Cuba and Spain, Daniel Fried, U.S. Assistant Secretary for European and Eurasian Affairs, has commented in 2007 that:

Spain has enormous influence in Cuba. Hundreds of thousands of Cubans less than a hundred years ago emigrated from Spain to Cuba. You have enormous influence there – direct and indirect and cultural influence. I would hope that influence would be brought to bear for democracy. I'm not saying that Spain has to agree with all American tactics about Cuba. Forget about American tactics. You can agree with them; you can not agree with them; you can agree with some and not others. Forget about it. Don't look at Cuba through the eyes of how you feel about America or the Bush Administration or anything else. Forget about us. Think about the Cuban people and their right to freedom, and think about your own history.

— Daniel Freid[72]

Venezuela and Bolivia

In addition to policy differences towards Cuba, the United States and Spain have been at variance in their dealings with Venezuela under Hugo Chávez and Bolivia under Evo Morales, both of them socialists.[70] Spain under Zapatero was initially friendly to both regimes. However, Morales’ plan to nationalize the gas sector of Bolivia caused tension with Spain, as Repsol, a Spanish company, has major interests in that South American country.[70] In regards to Venezuela, Zapatero also took issue with Chávez's elected socialist government. Spain's relations with Venezuela were further worsened by the November 10, 2007 incident at the Ibero-American Summit in Santiago, Chile, in which King Juan Carlos told Chávez to "shut up".

However, despite its waning support for Chávez, Spain stated in May 2007 that it would pursue a €1.7 billion, or $2.3 billion, contract to sell unarmed aircraft and boats to Venezuela.[70]

New stage in relations: 2009–present

Three days after Barack Obama was elected as the 44th President of the United States, he had a telephone conversation with Zapatero, which aides say lasted five to ten minutes.[73] Spanish Foreign Minister Miguel Ángel Moratinos visited Washington to meet Secretary of State Hillary Clinton a month after the new American administration was inaugurated. After this meeting, Moratinos told reporters that Spain was ready to take some prisoners from the closing Guantanamo Bay detention camp, provided that the judicial conditions were acceptable.[74] Moratinos also commented that "a new stage in relations between the United States and Spain is opening that is more intense, more productive".[75]

Obama and Zapatero met face-to-face for the first time on April 2, 2009, at the G20 London Summit. Both leaders participated in the NATO Summit in Strasbourg-Kehl, where Spain committed an additional 450 troops to its previous military contingent of 778 in Afghanistan.[76] Commentators said the decision may have been partially motivated by the Zapatero government's desire to curry favor with the new administration in Washington.[77] Days later at the EU-U.S. Summit in Prague the two held a 45-minute meeting, and afterwards shared a photo-op for the press, where Obama called Zapatero a friend, and said he thinks that the two nations would establish an even stronger relationship in the years to come. This was the first formal meeting between heads of government of Spain and the United States since 2004.[78][79]

In February 2010, Obama met with Zapatero at the United States Capitol a few days after Obama announced he would not attend the EU-U.S. summit in Madrid in May.[80] Two weeks later, Obama met with King Juan Carlos I. Juan Carlos I was the first European head of state to meet with Obama in the White House, where he has met with John F. Kennedy in 1962, Gerald Ford in 1976, Ronald Reagan in 1987, and Bill Clinton in 1993.[81]

In June 2018 King Felipe VI and Josep Borrell, minister of Foreign Affairs, Cooperation and European Union, made an official visit to the US, visiting New Orleans, San Antonio and Washington, D.C. The King was received by Donald Trump on 19 June. Meanwhile, Borrell had a meeting with Mike Pompeo, where the Spanish delegation showed concern for the US protectionist drift and discrepancies between the two countries were found in regards to their approach to migration policies.[82]

Diplomatic missions

|

|

- Embassy of Spain in Washington, D.C.

- Consulate-General of Spain in San Francisco

Embassy of the United States in Madrid

Embassy of the United States in Madrid Consulate-General of the United States in Barcelona

Consulate-General of the United States in Barcelona

Polls

According to 2012 the USA Global Leadership Report, 34% of Spaniards approve of U.S. leadership, with 33% disapproving and 34% uncertain.[83] According to a 2013 BBC World Service Poll, 43% of Spanish people view the USA influence positively, with only 25% expressing a negative view.[84] A 2017 survey conducted by the Pew Research Center showed 60% of Spaniards had a negative view of the US, with only 31% having a positive view.[85] The same study also showed only 7% of Spaniards had confidence in the current USA leader, President Donald Trump,[86] with 70% having no confidence in the incumbent president.[87]

Country comparison

| Kingdom of Spain | United States of America | |

|---|---|---|

| Coat of arms | .svg.png) |

|

| Flag |  |

|

| Time zones | 2 | 9 |

| Population | 46,354,321 | 329,562,579 |

| Area | 505,990 km² (195,360 sq mi) | 9,833,634 km² (3,796,787 sq mi) |

| Population density | 92/km² (238/sq mi) | 35/km² (87.4/sq mi) |

| Capital | Madrid | Washington, D.C. |

| Largest city | Madrid – 3,141,991 Barcelona – 1,620,343 Valencia – 791,413 |

New York City – 8,600,710 Los Angeles – 3,999,759 Chicago – 2,716,450 |

| Established | 20 January 1479 (Unification) 9 June 1715 (Centralization) |

4 July 1776 (Declaration) 3 September 1783 (Recognition) |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy | Federal presidential constitutional republic |

| Current Leaders | Monarch: Felipe VI | President: Donald Trump (Republican Party) |

| Prime Minister:[88] Pedro Sánchez (PSOE) | Vice President: Michael Pence (R) | |

| Legislature | Cortes Generales | Congress |

| Senate President: María Pilar Llop Cuenca (PSOE) |

Senate President pro tempore: Chuck Grassley (R) | |

| Congress of Deputies President: Meritxell Batet Lamaña (PSC) |

House of Representatives Speaker: Nancy Pelosi (D) | |

| Judiciary | Supreme Court President: Carlos Lesmes Serrano |

Supreme Court Chief Justice: John Roberts |

| National language | Spanish | English |

| Religion | 68.9% Catholic 27.1% Irreligion 2.8% Other Religions[89] |

48.5% Protestant 22.7% Catholic 1.8% Mormon 21.3% Irreligion 2.1% Judaism 2.7% Other Religions[90] |

| Ethnic groups | 88% Spanish Nationals 12% Immigrants |

72.4% European American 12.6% African American 4.8% Asian American 0.9% American Indian and Alaska Native 0.2% Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander 6.2% Other 2.9% two or more races[91] |

| GDP (nominal) | US$1.864 trillion ($40,290 per capita) | US$17.416 trillion ($54,390 per capita) |

See also

References

- Weber, David J. (2005). "The Spanish Borderlands, Historiography Redux". The History Teacher. 39 (1): 43–56. doi:10.2307/30036743. ISSN 0018-2745. JSTOR 30036743.

- Williamson, D. G. (November 5, 2013). The Age of the Dictators: A Study of the European Dictatorships, 1918-53. Routledge. p. 481. ISBN 978-1-317-87014-2.

- España-Los EUA: una historia de amor y odio

- Even worse, i (10th ed. 1980) p 32-33.

- Hernández Franco 1991, p. 185.

- Chávez, Thomas E (2002). Spain and the Independence of the United States: An Intrinsic Gift. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. p. 12. ISBN 0-8263-2794-X.

- Paul Johnson, A History of the American People (New York: HarperCollins, 1997), 362.

- Samuel Flagg Bemis, The Diplomacy Of The American Revolution (1935, 1957) pp 95-102. online

- John Ferling, A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic (2003), pp. 211–212

- Alan Taylor. American Revolutions A Continental History, 1750–1804 (2016), pp. 345–346

- George Herring, From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776 (2008), pp. 46–47

- Lawrence S. Kaplan, Colonies into Nation: American Diplomacy 1763-1801 (1972) pp 168-71.

- Jane M. Berry, "The Indian Policy of Spain in the Southwest 1783-1795." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 3.4 (1917): 462-477. online

- Arthur P. Whitaker, "Spain and the Cherokee Indians, 1783-98." North Carolina Historical Review 4.3 (1927): 252-269. online

- Roy F. Nichols, "Trade Relations and the Establishment of the United States Consulates in Spanish America, 1779-1809." The Hispanic American Historical Review 13.3 (1933): 289-313.

- Arthur P. Whitaker, "Reed and Forde: Merchant Adventurers of Philadelphia: Their Trade with Spanish New Orleans." Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 61.3 (1937): 237-262. online

- Javier Cuenca-Esteban, "British 'Ghost' Exports, American Middlemen, and the Trade to Spanish America, 1790–1819: A Speculative Reconstruction." William & Mary Quarterly 71.1 (2014): 63-98. online

- Kaplan, 166-74.

- Stuart Leibiger (2012). A Companion to James Madison and James Monroe. pp. 569–70. ISBN 9781118281437.

- James W. Cortada, "Spain and the American Civil War: Relations at Mid-century, 1855–1868" (American Philosophical Society, 1980), 3.

- Other War of 1812: The Patriot War and the American Invasion of Spanish East Florida, The | Alabama Review | Find Articles at BNET.com

- James W. Cortada, "Spain and the American Civil War: Relations at Mid-century, 1855–1868" (American Philosophical Society, 1980), 6.

- Quoted in James W. Cortada, "Spain and the American Civil War: Relations at Mid-century, 1855–1868" (American Philosophical Society, 1980), 9.

- James W. Cortada, "Spain and the American Civil War: Relations at Mid-century, 1855–1868" (American Philosophical Society, 1980), 9.

- Quoted in James W. Cortada, "Spain and the American Civil War: Relations at Mid-century, 1855–1868," Transactions of the American Philosophical Society (1980) Volume 70, Part 4, p. 105.

- Cortada, "Spain and the American Civil War p. 7.

- Cuba and the United States : A chronological History Archived 2007-12-29 at the Wayback Machine Jane Franklin

- Hugh Thomas. Cuba : The pursuit for freedom. pp. 134–5

- Quotes from Cortada, "Spain and the American Civil War" pp 26, 28..

- Cortada, "Spain and the American Civil War" p. 30.

- James W. Cortada, "Spain and the American Civil War: Relations at Mid-century, 1855–1868" (American Philosophical Society, 1980), 53–4.

- James W. Cortada, "Spain and the American Civil War: Relations at Mid-century, 1855–1868" (American Philosophical Society, 1980), 57.

- "The Price of Freedom: Americans at War – Spanish–American War". National Museum of American History. 2005.

- Proposicion del Capitan General Ramon Blanco Erenas

- Ramón Blanco y Erenas

- Solsten, and Meditz. Spain: A country study (1988)

- First World War.com – Feature Articles – Spain During the First World War

- Rothgeb, 2001, 32–33

- "INVITATION TO A TARIFF WAR.; Fordney Bill, if Enacted, Will Force Other Countries to Retaliate as Spain Has Done" (PDF). The New York Times. July 18, 1921.

- COOLIDGE GREETS ALFONSO ON PHONE; First Use by the President of Transa... – Free Preview – The New York Times

- HOW SPAIN VIEWS US.; "A Nation of Realities," Says El Sol -Urges Effo... – Article Preview – The New York Times

- Luis Araquistáin, El Peligro Yanqui (Madrid: Publicaciones españa, 1921).

- C. Brian Morris, This Loving Darkness: The Cinema and Spanish Writers 1920–1936 (Oxford University Press, 1980), 129.

- J. David Valaik, "Catholics, neutrality, and the Spanish embargo, 1937-1939." Journal of American History 54.1 (1967): 73-85. online

- Dominic Tierney (2007). FDR and the Spanish Civil War: Neutrality and Commitment in the Struggle that Divided America. pp. 106–8, 183–84. ISBN 978-0822340768.

- Beevor, p.138

- Beevor (2006), p.126

- Cary Nelson (ed.), The Wound and the Dream: Sixty Years of American Poems about the Spanish Civil War (Chicago: University of Illinois, 2002).

- Quoted in Cary Nelson (ed.), The Wound and the Dream: Sixty Years of American Poems about the Spanish Civil War (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2002), 112.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 6, 2006. Retrieved March 5, 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- David S. Brown (2008). Richard Hofstadter: An Intellectual Biography. pp. 42–43. ISBN 9780226076379.

- Andrew N. Buchanan, "Washington's 'silent ally' in World War II? United States policy towards Spain, 1939–1945", Journal of Transatlantic Studies (2009) 7#2, pp 93–117.

- Emmet Kennedy, "Ambassador Carlton J. H. Hayes's Wartime Diplomacy: Making Spain a Haven from Hitler", Diplomatic History (2012) 36#2, pp. 237–260.

- Trudy Alexy, The Mezuzah in the Madonna's Foot, (1993) pp. 154–5.

- John P. Willson, "Carlton J. H. Hayes, Spain, and the Refugee Crisis, 1942–1945", American Jewish Historical Quarterly (1972) 62#2, pp 99–110.

- Matthew Paul Berg; Maria Mesner (2009). After Fascism: European Case Studies in Politics, Society, and Identity Since 1945. p. 52. ISBN 9783643500182.

- Mark S. Byrnes,"'Overruled and Worn Down': Truman Sends an Ambassador to Spain." Presidential Studies Quarterly 29.2 (1999): 263-279.

- US Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1954 (1954) p 926 online

- Pardo Sanz, Rosa. "La etapa Castiella y el final del régimen" (PDF). Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia. p. 19.

- Powell 2007, p. 223.

- Powell 2007, p. 251.

- Powell 2007, pp. 227-229; 250.

- John T. Woolley and Gerhard Peters, Toasts of the President and General Francisco Franco of Spain at a State Dinner in Madrid, The American Presidency Project. U of California Santa Barbara; accessed 24 May 2008.

- New York Times. "Nixon Asserts Franco Won Respect for Spain." November 21, 1975, page 16.

- Richard Nixon: Toasts of the President and Prince Juan Carlos of Spain

- Federico Coullaut-Valera, Carlos III, Los Angeles

- Spain (01/08)

- elmundo.es – Zapatero anuncia la retirada inmediata de las tropas de Irak

- Ahead of rare talks, Rice slams Spain over Cuba – USATODAY.com

- Spain welcomes Rice with hope for better ties – International Herald Tribune

- "Fact checking the Biden-Palin debate". BBC News. October 3, 2008. Retrieved October 5, 2008.

- U.S.-Spain Relations

- "Six More Foreign-Leader Calls for Obama". Washington Post. November 7, 2008. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- "Miguel Ángel Moratinos meets with Hillary Clinton". Typically Spanish. February 24, 2009. Archived from the original on February 27, 2009. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- "Spain may take Guantanamo inmates". BBC News. February 24, 2009. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- "Spain to send 450 troops to Afghanistan during polls". Thaindian News. April 5, 2009. Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- "Spain commits more troops to Afghanistan in overture to Obama". The Christian Science Monitor.

- "Zapatero holds 45 minute meeting with Obama in Prague". Typically Spanish. April 5, 2009. Archived from the original on April 9, 2009. Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- "Obama and Zapatero herald 'new era' in Spanish-American relations". ThinkSpain. April 5, 2009. Retrieved April 6, 2009.

- "Zapatero says Obama still has EU's trust after summit snub – Summary". Earth Times. February 5, 2010. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- "El Rey será el primer jefe de Estado europeo al que reciba Obama en la Casa Blanca". Diaro Sur (in Spanish). February 17, 2010. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- "Trump asegura que irá a España y califica de "excelente" la relación". Agencia EFE. June 19, 2018.

- The USA Global Leadership Project Report – 2012 Gallup

- 2013 World Service Poll BBC

- "Trump Unpopular Worldwide, American Image Suffers". June 26, 2017.

- "Trump Unpopular Worldwide, American Image Suffers". June 26, 2017.

- "Trump Unpopular Worldwide, American Image Suffers". June 26, 2017.

- Literally President of the Government but formally known by English-speaking nations and formally translated by the European Commission Directorate-General in English as Prime Minister

- "CIA – The World Factbook – Spain". Cia.gov. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- Newport, Frank. "2017 Update on Americans and Religion". Gallup. Retrieved February 25, 2019.

- "2010 Census Data". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 2, 2011. Retrieved 2011-03-29.

Further reading

- Beevor, Antony, The Battle for Spain, Penguin Books, 2006., on the 1930s

- Bowen, Wayne H. Truman, Franco's Spain, and the Cold War (U of Missouri Press, 2017). 197 pp.

- Calvo-González, Oscar. "Neither a carrot nor a stick: American foreign aid and economic policymaking in Spain during the 1950s." Diplomatic History (2006) 30#3 pp: 409–438. online

- Chadwick, French Ensor. The Relations of the United States and Spain: Diplomacy (1909) online.

- Gavin, Victor. "The Nixon and Ford Administrations and the Future of Post-Franco Spain (1970–6)." International History Review 38.5 (2016): 930-942. online

- Halstead, Charles R. "Historians in Politics: Carlton J.H. Hayes as American Ambassador to Spain 1942–45", Journal of Contemporary History (1975): 383–405. in JSTOR

- Hernández Franco, Juan (1991). "El gobierno español ante la independencia de los Estados Unidos. Gestión de Floridablanca (1777-1783)" (PDF). Anales de Historia Contemporánea (in Spanish). Murcia: Universidad de Murcia. 8. ISSN 1989-5968.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jimenez, Francisco Javier Rodriguez et al., eds. U.S. Public Diplomacy and Democratization in Spain: Selling Democracy? (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015). xii, 237 pp.

- Kennedy, Emmet. "Ambassador Carlton J. H. Hayes's Wartime Diplomacy: Making Spain a Haven from Hitler", Diplomatic History (2012) 36#2, pp 237–260. online

- Offner, John L. An unwanted war: The diplomacy of the United States and Spain over Cuba, 1895–1898 (1992). online

- Payne, Stanley G. The Franco Regime: 1936–1975 (University of Wisconsin Press, 1987)

- Pederson, William D. ed. A Companion to Franklin D. Roosevelt (2011) online pp 653–71; historiography of FDR's policies

- Powell, Charles (2007). "Henry Kissinger y España: de la dictadura a la democracia (1969-1977)". Historia y Política. Ideas, Procesos y Movimientos Sociales. Madrid: UCM; CEPC; UNED (17): 223–251. ISSN 1575-0361.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rosendorf, N. Franco Sells Spain to America: Hollywood, Tourism and Public Relations as Postwar Spanish (2014)

- Rothgeb, John (2001). U.S. Trade Policy. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. ISBN 1-56802-522-X.

- Rubottom, R. Richard, and J. Carter Murphy. Spain and the United States: Since World War II (Praeger, 1984)

- Shneidman, Jerome Lee. Spain & Franco, 1949-59: Quest for international acceptance (1973) online free to borrow

- Solsten, Eric, and Sandra W. Meditz. Spain: A country study (Library of Congress, 1988) online

- Whitaker, Arthur P. Spain and the Defense of the West: Ally and Liability (1961)

External links

- History of Spain – U.S. relations

- (in Spanish) España-EE UU: una historia de amor y odio

- Spain and the United States

- U.S.-Spain Relations: Interview with Daniel Fried, Assistant Secretary for European and Eurasian Affairs, May 25, 2007

- U.S. Mission in Spain

- Ahead of rare talks, Rice slams Spain over Cuba

- Spain welcomes Rice with hope for better ties

- "A Period of Turbulent Change: Spanish-US Relations Since 2002", Manuel Iglesias-Cavicchioli, The Whitehead Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations, Summer/Fall 2007