French Foreign Legion

The French Foreign Legion (FFL; French: Légion étrangère, French pronunciation: [leʒjɔ̃ etʁɑ̃ʒɛʁ], L.É.) is a military service branch of the French Army established in 1831. Legionnaires are highly trained infantry soldiers and the Legion is unique in that it is open to foreign recruits willing to serve in the French Armed Forces. When it was founded, the French Foreign Legion was not unique; other foreign formations existed at the time in France.[8] The Foreign Legion is today known as a unit whose training focuses on traditional military skills and on its strong esprit de corps, as its men come from different countries with different cultures. This is a way to strengthen them enough to work as a team. Consequently, training is often described as not only physically challenging, but also very stressful psychologically. French citizenship may be applied for after three years' service.[9] The Legion is the only part of the French military that does not swear allegiance to France, but to the Foreign Legion itself.[10] Any soldier who gets wounded during a battle for France can immediately apply to be a French citizen under a provision known as "Français par le sang versé" ("French by spilled blood").[9] As of 2018, members came from 140 countries.

| French Foreign Legion | |

|---|---|

| Légion étrangère | |

The Foreign Legion's grenade emblem and colours | |

| Active | 10 March 1831 – present |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Foreign legion |

| Role | Airborne Infantry, Light Infantry, Armoured Infantry, Armoured Cavalry, Combat Engineers, Airborne Engineers, Regimental Foreign Military Police |

| Size | C. 8,900 men in 11 regiments and one sub-unit (as of January 2018)[1] |

| Garrison/HQ |

|

| Nickname(s) | The Legion (English) La Légion (French) |

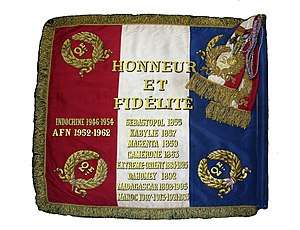

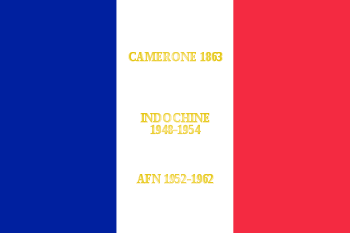

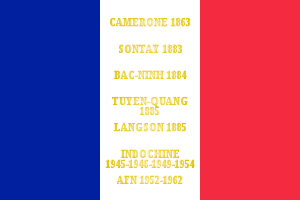

| Motto(s) | Legio Patria Nostra (The Legion is our Fatherland)[2] Honneur et Fidélité (Honour and Fidelity)[2] |

| Branch colours Colour of Beret | Red and Green Green[3][4] |

| March | Le Boudin[5] |

| Anniversaries | Camerone Day (30 April) |

| Engagements |

|

| Website | www www |

| Commanders | |

| Commandant | Major General Denis Mistral[7] |

| Ceremonial chief | Wooden hand of Captain Jean Danjou carried by a selected officer or legionnaire from Foreign Legion Pionniers[3] |

| Notable commanders | General Paul-Frédéric Rollet |

| Insignia | |

| Identification symbol |  |

| Legion flash |  |

| Abbreviation | FFL (English) L.É. (French) |

Since 1831, the Legion has suffered the loss of nearly 40,000 men on active service[11] in France, Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, Madagascar, West Africa, Mexico, Italy, the Crimea, Spain, Indo-China, Norway, Syria, Chad, Zaïre, Lebanon, Central Africa, Gabon, Kuwait, Rwanda, Djibouti, former Yugoslavia, Somalia, the Republic of Congo, Ivory Coast, Afghanistan, Mali, as well as others. The French Foreign Legion was primarily used to help protect and expand the French colonial empire during the 19th century. The Foreign Legion was initially stationed only in Algeria, where it took part in the pacification and development of the colony. Subsequently, the Foreign Legion was deployed in a number of conflicts, including the First Carlist War in 1835, the Crimean War in 1854, the Second Italian War of Independence in 1859, the French intervention in Mexico in 1863, the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, the Tonkin Campaign and Sino-French War in 1883, supporting growth of the French colonial empire in Sub-Saharan Africa, the Second Franco-Dahomean War in 1892, the Second Madagascar expedition in 1895 and the Mandingo Wars in 1894. In World War I, the Foreign Legion fought in many critical battles on the Western Front. It played a smaller role in World War II than in World War I, though having a part in the Norwegian, Syrian and North African campaigns. During the First Indochina War (1946–1954), the Foreign Legion saw its numbers swell. The FFL lost a large number of men in the catastrophic Battle of Dien Bien Phu.

During the Algerian War of Independence (1954–1962), the Foreign Legion came close to being disbanded after some officers, men, and the highly decorated 1st Foreign Parachute Regiment (1er REP) took part in the Generals' putsch. Operations during this period included the Suez Crisis, the Battle of Algiers and various offensives launched by General Maurice Challe including Operations Oranie and Jumelles. In the 1960s and 1970s, Legion regiments had additional roles in sending units as a rapid deployment force to preserve French interests – in its former African colonies and in other nations as well; it also returned to its roots of being a unit always ready to be sent to conflict zones around the world. Some notable operations include: the Chadian–Libyan conflict in 1969–1972 (the first time that the Legion was sent in operations after the Algerian War), 1978–1979, and 1983–1987; Kolwezi in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo in May 1978. In 1981, the 1st Foreign Regiment and Foreign Legion regiments took part in the Multinational Force in Lebanon. In 1990, Foreign Legion regiments were sent to the Persian Gulf and participated in Opération Daguet, part of Division Daguet. Following the Gulf War in the 1990s, the Foreign Legion helped with the evacuation of French citizens and foreigners in Rwanda, Gabon and Zaire. The Foreign Legion was also deployed in Cambodia, Somalia, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina. In the mid- to late 1990s, the Foreign Legion was deployed in the Central African Republic, Congo-Brazzaville and in Kosovo. The Foreign Legion also took part in operations in Rwanda in 1990–1994; and the Ivory Coast in 2002 to the present. In the 2000s, the Foreign Legion was deployed in Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan, Operation Licorne in Ivory Coast, the EUFOR Tchad/RCA in Chad, and Operation Serval in the Northern Mali conflict.[12] Other countries have tried to emulate the French Foreign Legion model.

History

The French Foreign Legion was created by Louis Philippe,[13] the King of France, on 10 March 1831[14] from the foreign regiments of the Kingdom of France. Recruits included soldiers from the recently disbanded Swiss and German foreign regiments of the Bourbon monarchy.[15] The Royal Ordinance for the establishment of the new regiment specified that the foreigners recruited could only serve outside France.[16] The French expeditionary force that had occupied Algiers in 1830 was in need of reinforcements and the Legion was accordingly transferred by sea in detachments from Toulon to Algeria.[9][17]

The Foreign Legion was primarily used, as part of the Armée d'Afrique, to protect and expand the French colonial empire during the 19th century, but it also fought in almost all French wars including the Franco-Prussian War, World War I and World War II. The Foreign Legion has remained an important part of the French Army and sea transport protected by the French Navy, surviving three Republics, the Second French Empire, two World Wars, the rise and fall of mass conscript armies, the dismantling of the French colonial empire, and the loss of the Foreign Legion's base, Algeria.

Conquest of Algeria 1830–1847

Created to fight "outside mainland France", the Foreign Legion was stationed in Algeria, where it took part in the pacification and development of the colony, notably by drying the marshes in the region of Algiers. The Foreign Legion was initially divided into six "national battalions" (Swiss, Poles, Germans, Italians, Spanish, and Dutch-Belgian).[18] Smaller national groups, such as the ten Englishmen recorded in December 1832, appear to have been placed randomly.

In late 1831, the first legionnaires landed in Algeria, the country that would be the Foreign Legion's homeland for 130 years and shape its character. The early years in Algeria were hard on the legion because it was often sent to the worst postings and received the worst assignments, and its members were generally uninterested in the new colony of the French.[19] The Legion served alongside the Battalions of Light Infantry of Africa, formed in 1832, which was a penal military unit made up of men with prison records who still had to do their military service or soldiers with serious disciplinary problems.

The Foreign Legion's first service in Algeria came to an end after only four years, as it was needed elsewhere.

Carlist War 1835–1839

To support Isabella's claim to the Spanish throne against her uncle, the French government decided to send the Foreign Legion to Spain. On 28 June 1835, the unit was handed over to the Spanish government. The Foreign Legion landed via sea at Tarragona on 17 August with around 1,400 who were quickly dubbed Los Algerinos (the Algerians) by locals because of their previous posting.

The Foreign Legion's commander immediately dissolved the national battalions to improve the esprit de corps. Later, he also created three squadrons of lancers and an artillery battery from the existing force to increase independence and flexibility. The Foreign Legion was dissolved on 8 December 1838, when it had dropped to only 500 men. The survivors returned to France, many reenlisting in the new Foreign Legion along with many of their former Carlist enemies.

Crimean War

On 9 June 1854, the French ship Jean Bart embarked four battalions of the Foreign Legion for the Crimean Peninsula. A further battalion was stationed at Gallipoli as brigade depot.[20] Eight companies drawn from both regiments of the Foreign Legion took part in the Battle of Alma (20 September 1854). Reinforcements by sea brought the Legion contingent up to brigade strength. As the "Foreign Brigade", it served in the Siege of Sevastopol, during the winter of 1854–1855.

The lack of equipment was particularly challenging and cholera hit the Allied expeditionary force. Nevertheless, the "leather bellies" (the nickname given to the legionnaires by the Russians because of the large cartridge pouches that they wore attached to their waist-belts), performed well. On 21 June 1855, the Third Battalion, left Corsica for Crimea.

On 8 September the final assault was launched on Sevastopol. Two days later, the Second Foreign Regiment with flags and band playing ahead, marched through the streets of Sevastopol. Although initial reservations had been expressed about whether the Legion should be used outside Africa,[20] the Crimean experience established its suitability for service in European warfare, as well as making a cohesive single entity of what had previously been two separate foreign regiments.[21] Total Legion casualties in the Crimea were 1,703 killed and wounded.

Italian Campaign 1859

Like the rest of the "Army of Africa", the Foreign Legion provided detachments in the campaign of Italy. Two foreign regiments, grouped with the 2nd Regiment of Zouaves, were part of the Second Brigade of the Second Division of Mac Mahon's Corps. The Foreign Legion acquitted itself particularly well against the Austrians at the battle of Magenta (4 June 1859) and at the Battle of Solferino (24 June). Legion losses were significant and the 2nd Foreign Regiment lost Colonel Chabrière, its commanding officer. In gratitude, the city of Milan awarded, in 1909, the "commemorative medal of deliverance", which still adorns the regimental flags of the Second Regiment.[22]

Mexican Expedition 1863–1867

The 38,000 strong French expeditionary force dispatched to Mexico via sea between 1862 and 1863 included two battalions of the Foreign Legion, increased to six battalions by 1866. Small cavalry and artillery units were raised from legionnaires serving in Mexico. The original intention was that Foreign Legion units should remain in Mexico for up to six years to provide a core for the Imperial Mexican Army.[23] However the Legion was withdrawn with the other French forces during February–March 1867.

It was in Mexico on 30 April 1863 that the Legion earned its legendary status. A company led by Captain Jean Danjou, numbering 62 Legionnaires and 3 Legion officers, was escorting a convoy to the besieged city of Puebla when it was attacked and besieged by three thousand Mexican loyalists,[24] organised in two battalions of infantry and cavalry, numbering 2,200 and 800 respectively. The Legion detachment under Captain Jean Danjou, Sous-Lieutenant Jean Vilain, Sous-Lieutenant Clément Maudet[25] made a stand in the Hacienda de la Trinidad – a farm near the village of Camarón. When only six survivors remained, out of ammunition, a bayonet assault was launched in which three of the six were killed. The remaining three wounded men were brought before the Mexican commander Colonel Milan, who allowed them to return to the French lines as an honor guard for the body of Captain Danjou. The captain had a wooden hand, which was later returned to the Legion and is now kept in a case in the Legion Museum at Aubagne, and paraded annually on Camerone Day. It is the Foreign Legion's most precious relic.

During the Mexican Campaign, 6,654 French died. Of these, 1,918 were from a single regiment of the Legion.[26]

Franco-Prussian War 1870

According to French law, the Foreign Legion was not to be used within Metropolitan France except in the case of a national invasion,[27] and was consequently not a part of Napoleon III's Imperial Army that capitulated at Sedan. With the defeat of the Imperial Army, the Second French Empire fell and the Third Republic was created.

The new Third Republic was desperately short of trained soldiers following Sedan, so the Foreign Legion was ordered to provide a contingent. On 11 October 1870 two provisional battalions disembarked via sea at Toulon, the first time the Foreign Legion had been deployed in France itself. It attempted to lift the Siege of Paris by breaking through the German lines. It succeeded in retaking Orléans, but failed to break the siege. In January 1871, France capitulated but civil war soon broke out, which led to revolution and the short-lived Paris Commune. The Foreign Legion participated in the suppression of the Commune,[28] which was crushed with great bloodshed.

Tonkin Campaign and Sino-French War 1883–1888

The Foreign Legion's First Battalion (Lieutenant-Colonel Donnier) sailed to Tonkin in late 1883, during the period of undeclared hostilities that preceded the Sino-French War (August 1884 to April 1885), and formed part of the attack column that stormed the western gate of Sơn Tây on 16 December. The Second and Third Infantry Battalions (chef de bataillon Diguet and Lieutenant-Colonel Schoeffer) were also deployed to Tonkin shortly afterwards, and were present in all the major campaigns of the Sino-French War. Two Foreign Legion companies led the defence at the celebrated Siege of Tuyên Quang (24 November 1884 to 3 March 1885). In January 1885 the Foreign Legion's 4th Battalion (chef de bataillon Vitalis) was deployed to the French bridgehead at Keelung (Jilong) in Formosa (Taiwan), where it took part in the later battles of the Keelung Campaign. The battalion played an important role in Colonel Jacques Duchesne's offensive in March 1885 that captured the key Chinese positions of La Table and Fort Bamboo and disengaged Keelung.

In December 1883, during a review of the Second Legion Battalion on the eve of its departure for Tonkin to take part in the Bắc Ninh Campaign, General François de Négrier pronounced a famous mot: Vous, légionnaires, vous êtes soldats pour mourir, et je vous envoie où l'on meurt! ('You, Legionnaires, you are soldiers in order to die, and I'm sending you to where one dies!')

Colonisation of Africa

As part of the Army of Africa, the Foreign Legion contributed to the growth of the French colonial empire in Sub-Saharan Africa. Simultaneously, the Legion took part to the pacification of Algeria, suppressing various tribal rebellions and razzias.

Second Franco-Dahomean War 1892–1894

In 1892, King Behanzin was threatening the French protectorate of Porto-Novo in modern-day Benin and France decided to intervene. A battalion, led by commandant Faurax Montier, was formed from two companies of the First Foreign Regiment and two others from the second regiment. From Cotonou, the legionnaires marched to seize Abomey, the capital of the Kingdom of Dahomey. Two and a half months were needed to reach the city, at the cost of repeated battles against the Dahomean warriors, especially the Amazons of the King. King Behanzin surrendered and was captured by the legionnaires in January 1894.

Second Madagascar Expedition 1894–1895

In 1895, a battalion, formed by the First and Second Foreign Regiments, was sent to the Kingdom of Madagascar, as part of an expeditionary force whose mission was to conquer the island. The foreign battalion formed the backbone of the column launched on Antananarivo, the capital of Madagascar. After a few skirmishes, the Queen Ranavalona III promptly surrendered.[29][30] The Foreign Legion lost 226 men, of whom only a tenth died in actual fighting. Others, like much of the expeditionary force, died from tropical diseases.[29] Despite the success of the expedition, the quelling of sporadic rebellions would take another eight years until 1905, when the island was completely pacified by the French under Joseph Gallieni.[29] During that time, insurrections against the Malagasy Christians of the island, missionaries and foreigners were particularly terrible.[31] Queen Ranavalona III was deposed in January 1897 and was exiled to Algiers in Algeria, where she died in 1917.[32]

Mandingo War 1898

From 1882 until his capture, Samori Ture, ruler of the Wassoulou Empire, fought the French colonial army, defeating them on several occasions, including a notable victory at Woyowayanko (2 April 1882), in the face of French heavy artillery. Nonetheless, Samori was forced to sign several treaties ceding territory to the French between 1886 and 1889. Samori began a steady retreat, but the fall of other resistance armies, particularly Babemba Traoré at Sikasso, permitted the colonial army to launch a concentrated assault against his forces. A battalion of two companies from the 2nd Foreign Regiment was created in early 1894 to pacify the Niger. The Legionnaires' victory at the fortress of Ouilla and police patrols in the region accelerated the submission of the tribes. On 29 September 1898, Samori Ture was captured by the French Commandant Gouraud and exiled to Gabon, marking the end of the Wassoulou Empire.

Marching Regiments of the Foreign Legion

World War I 1914–1918

The annexation of Alsace and Lorraine by Germany in 1871 led to numerous volunteers from the two regions enlisting in the Foreign Legion, which gave them the option of French citizenship at the end of their service[33]

With the declaration of war on 29 July 1914, a call was made for foreigners residing in France to support their adopted country. While many would have preferred direct enlistment in the regular French Army, the only option immediately available was that of the Foreign Legion. On one day only (3 August 1914) a reported 8,000 volunteers applied to enlist in the Paris recruiting office of the Legion.

In World War I, the Foreign Legion fought in many critical battles on the Western Front, including Artois, Champagne, Somme, Aisne, and Verdun (in 1917), and also suffered heavy casualties during 1918. The Foreign Legion was also in the Dardanelles and Macedonian front, and was highly decorated for its efforts. Many young foreigners volunteered for the Foreign Legion when the war broke out in 1914. There were marked differences between the idealistic volunteers of 1914 and the hardened men of the old Legion, making assimilation difficult. Nevertheless, the old and the new men of the Foreign Legion fought and died in vicious battles on the Western front, including Belloy-en-Santerre during the Battle of the Somme, where the poet Alan Seeger, after being mortally wounded by machine-gun fire, cheered on the rest of his advancing battalion.[34]

Interwar Period 1918–1939

While suffering heavy casualties on the Western Front the Legion had emerged from World War I with an enhanced reputation and as one of the most highly decorated units in the French Army.[35] In 1919, the government of Spain raised the Spanish Foreign Legion and modeled it after the French Foreign Legion.[35] General Jean Mordacq intended to rebuild the Foreign Legion as a larger military formation, doing away with the legion's traditional role as a solely infantry formation.[35] General Mordacq envisioned a Foreign Legion consisting not of regiments, but of divisions with cavalry, engineer, and artillery regiments in addition to the legion's infantry mainstay.[35] In 1920, decrees ordained the establishment of regiments of cavalry and artillery.[35] Immediately following the armistice the Foreign Legion experienced an increase of enlistments.[36] The Foreign Legion began the process of reorganizing and redeploying to Algeria.[35]

The Legion played a major part in the Rif War of 1920–25. In 1932, the Foreign Legion consisted of 30,000 men, serving in six multi-battalion regiments including the 1st Foreign Infantry Regiment 1er REI – Algeria, Syria and Lebanon; 2nd Foreign Infantry Regiment 2ème REI, 3rd Foreign Infantry Regiment 3ème REI, and 4th Foreign Infantry Regiment 4ème REI – Morocco, Lebanon; 5th Foreign Infantry 5ème REI – Indochina; and 1st Foreign Cavalry Regiment 1er REC – Lebanon, Tunisia and Morocco. In 1931, Général Paul-Frédéric Rollet assumed the role of 1st Inspector of the Foreign Legion, a post created at his initiative. While serving as Colonel of the 1st Foreign Infantry Regiment (1925–1931), Rollet was responsible for planning the centennial celebrations of the Legion's foundation; scheduling this event for Camarón Day 30 April 1931. He was subsequently credited with creating much of the modern mystique of the Legion by restoring or creating many of its traditions.

World War II 1939–1945

The Foreign Legion played a smaller role in World War II in mainland Europe than in World War I, though there was involvement in many exterior theatres of operations, notably sea transport protection through to the Norwegian, Syria-Lebanon, and North African campaigns. The 13th Demi-Brigade, formed for service in Norway, found itself in the UK at the time of the French Armistice (June 1940), was deployed to the British 8th Army in North Africa and distinguished itself in the Battle of Bir Hakeim (1942). Reflecting the divisions of the time, part of the Foreign Legion joined the Free French movement while another part served the Vichy government. German legionnaires were incorporated into the Wehrmacht's 90th Light Infantry Division in North Africa.[37]

The Syria–Lebanon Campaign of June 1941 saw legionnaire fighting legionnaire as the 13e D.B.L.E clashed with the 6th Foreign Infantry Regiment 6e REI at Damascus. Nevertheless, many legionnaires of the 6th Foreign Infantry Regiment 6e (dissolved on 31 December 1941) integrated the Marching Regiment of the Foreign Legion R.M.L.E in 1942. Later, a thousand of the rank-and-file of the Vichy Legion unit joined the 13e D.B.L.E. of the Free French forces which were also part as of September 1944 of Jean de Lattre de Tassigny's successful Amalgam of the French Liberation Army (French: Armée française de la Libération,), the (400,000 men) amalgam consisted of the Armistice Army, the Free French Forces and the French Forces of the Interior which formed Army B and were later part of the French 1st Army with forces also issued from the French Resistance.

Alsace-Lorraine

Following World War II, many French-speaking German former soldiers joined the Foreign Legion to pursue a military career, an option no longer possible in Germany including French German soldiers of Malgré-nous. It would have been considered problematic if the men from Alsace-Lorraine did not speak French. These French-speaking former German soldiers made up as much as 60 percent of the Legion during the war in Indochina. Contrary to popular belief however, French policy was to exclude former members of the Waffen-SS, and candidates for induction were refused if they exhibited the tell-tale blood type tattoo, or even a scar that might be masking it.[38]

The high percentage of Germans was contrary to normal policy concerning a single dominant nationality, and in more recent times Germans have made up a much smaller percentage of the Foreign Legion's composition.[39]

First Indochina War 1946–1954

During the First Indochina War (1946–54) the Foreign Legion saw its numbers swell due to the incorporation of World War II veterans. Although the Foreign Legion distinguished itself in a territory where it had served since the 1880s, it also suffered a heavy toll during this war. Constantly being deployed in operations, units of the Legion suffered particularly heavy losses in the climactic Battle of Dien Bien Phu, before the fortified valley finally fell on 7 May 1954. No fewer than 72,833 served in Indochina during the eight-year war. The Legion suffered the loss of 10,283 of its own men in combat: 309 officers, 1082 sous-officiers and 9092 legionnaires .

While only one of several Legion units involved in Indochina, the 1st Foreign Parachute Battalion (1er BEP) particularly distinguished itself, while being annihilated twice. It was renamed the 1st Foreign Parachute Regiment (1er REP) after its third reformation.[40]

The 1er BEP sailed to Indochina on 12 November and was then engaged in combat operations in Tonkin.[40] On 17 November 1950 the battalion parachuted into That Khé and suffered heavy losses at Coc Xa. Reconstituted on 1 March 1951, the battalion participated in combat operations at Cho Ben, on the Black River and in Annam.[40] On 21 November 1953 the reconstituted 1er BEP was parachuted into Dien Bien Phu.[40] In this battle, the unit lost 575 killed and missing.[40] Reconstituted for the third time on 19 May 1954, the battalion left Indochina on 8 February 1955.[40] The 1er BEP received five citations and the fourragère of the colors of the Médaille militaire[40] for its service in Indochina. The 1er BEP became the 1st Foreign Parachute Regiment (1er REP) in Algeria on 1 September 1955.

Dien Bien Phu fell on 7 May 1954 at 17:30.[41] The couple of hectares comprising the battlefield today are corn fields surrounding a stele which commemorates the sacrifices of those who died there. While the garrison of Dien Bien Phu included French regular, North African, and locally recruited (Indochinese) units, the battle has become associated particularly with the paratroops of the Foreign Legion.

During the Indochina War, the Legion operated several armoured trains which were an enduring Rolling Symbol during the chartered course duration of French Indochina. The Legion also operated various Passage Companies relative to the continental conflicts at hand.

Algerian War 1954–1962

Foreign Legion paratroops

Legion Lieutenant Colonel Pierre Paul Jeanpierre (1912–1958).[42]

The legion was heavily engaged in fighting against the National Liberation Front and the Armée de Libération Nationale (ALN). The main activity during the period 1954–1962 was as part of the operations of the 10th Parachute Division and 25th Parachute Division. The 1st Foreign Parachute Regiment, 1er REP, was under the command of the 10th Parachute Division (France), 10ème DP, and the 2nd Foreign Parachute Regiment, 2ème REP, was under the command of the 25th Parachute Division (France), 25ème DP. While both the 1st Foreign Parachute Regiment (1er REP), and the 2nd Foreign Parachute Regiment (2ème REP), were part of the operations of French parachute divisions (10ème DP and 25ème DP established in 1956), the Legion's 1st Foreign Parachute Regiment (1er REP), and the Legion's 2nd Foreign Parachute Regiment (2ème REP), are older than the French divisions. The 1er REP was the former thrice-reconstituted 1st Foreign Parachute Battalion (1er BEP) and the 2ème REP was the former 2nd Foreign Parachute Battalion (2ème BEP). Both battalions were renamed and their Legionnaires transferred from Indochina on 1 August 1954 to Algeria by 1 November 1954. Both traced their origins to the Parachute Company of the 3rd Foreign Infantry Regiment commanded by Legion Lieutenant Jacques Morin attached to the III/1er R.C.P.[43]

With the start of the War in Algeria on 1 November 1954, the two foreign participating parachute battalions back from Indochina, the 1st Foreign Parachute Battalion (1er BEP, III Formation) and the 2nd Foreign Parachute Battalion (2ème BEP), were not part of any French parachute divisions yet and were not designated as regiments until September and 1 December 1955 respectively.

Main operations during the Algerian War included the Battle of Algiers and the Bataille of the Frontiers, fought by 60,000 soldiers including French and Foreign Legion paratroopers. For paratroopers of the Legion, the 1st Foreign Parachute Regiment (1er REP) and 2nd Foreign Parachute Regiment (2ème REP), were the only known foreign active parachute regiments, exclusively commanded by Pierre Paul Jeanpierre for the 1er REP[42] and the paratrooper commanders of the 2ème REP.[44] The remainder of French paratrooper units of the French Armed Forces were commanded by Jacques Massu, Buchond, Marcel Bigeard, Paul Aussaresses. Other Legion offensives in the mountains in 1959 included operations Jumelles, Cigales, and Ariège in the Aures and the last in Kabylie.[42]

The image of the Legion as a professional and non-political force was tarnished when the elite 1st Foreign Parachute Regiment 1er REP, which was also part of the 10th Parachute Division played a leading role in the general's putsch of 1961[42] and was subsequently disbanded.

Generals' Putsch and reduction of Foreign Legion

Coming out of a difficult Indochinese conflict, the French Foreign Legion, reinforced cohesion by extending the duration of basic training. Efforts exerted were successful during this transit; however, entering in December 1960 and the revolt the generals, a crisis hit the legion putting its faith at the corps of the Army.[46]

For having rallied to the generals putsch of April 1961, the 1st Foreign Parachute Regiment 1er REP of the 10th Parachute Division was dissolved on 30 April 1961 at Zeralda.

In 1961, at the issue of the putsch, the 1st Mounted Saharan Squadron of the Foreign Legion[47](French: 1er Escadron Saharien Porté de la Légion Etrangère, 1er ESPLE) received the missions to assure surveillance and policing.

The independence of Algeria from the French in 1962 was traumatising since it ended with the enforced abandonment of the barracks command center at Sidi Bel Abbès established in 1842. Upon being notified that the elite regiment was to be disbanded and that they were to be reassigned, legionnaires of the 1er REP burned the Chinese pavilion acquired following the Siege of Tuyên Quang in 1884. The relics from the Legion's history museum, including the wooden hand of Captain Jean Danjou, subsequently accompanied the Legion to France. Also removed from Sidi Bel Abbès were the symbolic Legion remains of General Paul-Frédéric Rollet ( The Father of the Legion ), Legion officer Prince Count Aage of Rosenborg, and Legionnaire Heinz Zimmermann (last fatal casualty in Algeria).

The Legion acquired its parade song "Non, je ne regrette rien" ("No, I regret nothing"), a 1960 Édith Piaf song sung by Sous-Officiers and legionnaires as they left their barracks for re-deployment following the Algiers putsch of 1961. The song has remained a part of Legion heritage since.

The 1st Foreign Parachute Regiment 1er REP was disbanded on 30 April 1961.[42] However, the 2nd Foreign Parachute Regiment 2ème REP prevailed in existence, while most of the personnel of the Saharan Companies were integrated into the 1st Foreign Infantry Regiment, 2nd Foreign Infantry Regiment and 4th Foreign Infantry Regiment respectively.

Post-colonial Africa

By the mid-1960s the Legion had lost its traditional and spiritual home in French Algeria and elite units had been dissolved.[40] President de Gaulle considered disbanding it altogether but, being reminded of the Marching Regiments, and that the 13th Demi-Brigade was one of the first units to declare for him in 1940 and taking also into consideration the effective service of various Saharan units and performances of other Legions units, he chose instead to downsize the Legion from 40,000 to 8,000 men and relocate it to metropolitan France.[48] Legion units continued to be assigned to overseas service, although not in North Africa (see below).

1962–present

In the early 1960s, and besides ongoing global rapid deployments, the Legion also stationed forces on various continents while operating different function units.

From 1965 to 1967, the Legion operated several companies, including the 5th Heavy Weight Transport Company (CTGP), mainly in charge of evacuating the Sahara. The area of responsibility of some of these units extended from the confines of the in-between of the Sahara to the Mediterranean. Ongoing interventions and rapid deployments two years later and the following years included in part:

- 1969–1971 : interventions in Chad

- 1978–present : Peacekeeping operations around the Mediterranean, including the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon during the Global War on Terror

- 1978–1978 : Battle of Kolwezi (Zaïre)

- 1981–1984 : Peacekeeping operations in Lebanon at the corps of the United Nations Multinational Force during the Lebanese Civil War along with the 31ème Brigade which included the 1st Foreign Regiment 1er RE. Operation Épaulard I was spearheaded by Lieutenant-colonel Bernard Janvier. The Multinational Force also included the British Armed Forces 1st The Queen's Dragoon Guards, U.S. American contingents of United States Marine Corps and the United States Navy, the French Navy and 28 exclusive French Armed Forces regiments including French paratroopers regiments, companies, units of the 11th Parachute Brigade along with the 2nd Foreign Parachute Regiment 2e REP. The multinational force also included the Irish Armed Forces and units of the French National Gendarmerie, Italian paratroopers from the Folgore Brigade, and infantry units from the Bersaglieri regiments and Marines of the San Marco Battalion.

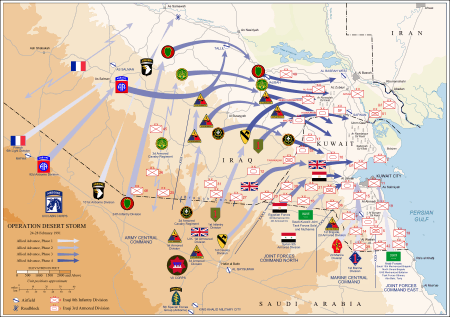

Gulf War 1990–1991

In September 1990, the 1st Foreign Regiment 1er RE, the 1st Foreign Cavalry Regiment 1er REC, the 2nd Foreign Parachute Regiment 2ème REP, the 2nd Foreign Infantry Regiment 2ème REI, and the 6th Foreign Engineer Regiment 6ème REG were sent to the Persian Gulf as a part of Opération Daguet along with the 1st Spahi Regiment, the 11th Marine Artillery Regiment, the 3rd Marine Infantry Regiment, the 21st Marine Infantry Regiment, the French Army Light Aviation, the Marine Infantry Tank Regiment, French paratroopers regiments including components of the 35th Parachute Artillery Regiment 35ème RAP, the 1st Parachute Hussard Regiment 1er RHP, the 17th Parachute Engineer Regiment 17ème RGP and other airborne contingents. Division Daguet was commanded by Général de brigade Bernard Janvier.

The Legion force, mainly comprising 27 different nationalities,[49] was attached to the French 6th Light Armoured Division 6ème D.L.B, whose mission was to protect the Coalition's left flank while cover fired by the marine's artillery. During the Gulf War, DINOPS operated in support of the U.S. Army's 82nd Airborne Division, and provided the EOD services to the division. After the cease fire took hold they conducted a joint mine clearing operation alongside a Royal Australian Navy Clearance Diver Team Unit.

After the four-week air campaign, coalition forces launched the ground offensive. They quickly penetrated deep into Iraq, with the Legion taking the As-Salman Airport, meeting little resistance. The war ended after a hundred hours of fighting on the ground, which resulted in very light casualties for the Legion.

Post 1991

- 1991: Evacuation of French citizens and foreigners in Rwanda, Gabon and Zaire.

- 1992: Cambodia and Somalia

- 1993: Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina

- 1995: Rwanda

- 1996: Central African Republic

- 1997: Congo-Brazzaville

- Since 1999: KFOR in Kosovo and North Macedonia

Global War on Terror 2001–present

- 2001–2014: Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan

- 2002–2003: Operation Licorne in Ivory Coast

- 2008: EUFOR Tchad/RCA in Chad

- 2013–2014: Operation Serval in the Northern Mali conflict[50]

Composition and organization

Prior to the end of the Algerian War the legion had not been stationed in mainland France except in wartime. Until 1962, the Foreign Legion headquarters, garrison quartier Vienot of Sidi Bel Abbès was in French Algeria. Today, some units of the Légion are in Corsica or overseas possessions (mainly in French Guiana, guarding Guiana Space Centre), while the rest are in the south of mainland France. Current headquarters, garrison quartier Vienot of Aubagne is in France, just outside Marseille. As a result of a recruiting drive in the wake of the November 2015 Paris attacks, the Legion will be 8,900 men strong in 2018.[51]

- Mainland France

- 1st Foreign Regiment (1er RE), based in Aubagne, France (HQ, selection and administration, other specific missions)

- 1st Foreign Cavalry Regiment (1er REC), based in Camp de Carpiagne (Bouches-du-Rhône), France (armoured troops)

- 1st Foreign Engineer Regiment (1er REG) former 6th Foreign Engineer Regiment (6ème REG), based in Laudun, France

- 2nd Foreign Infantry Regiment (2ème REI), based in Nîmes, France

- 2nd Foreign Engineer Regiment (2ème REG), based in St Christol, France

- 2nd Foreign Parachute Regiment (2ème REP), based in Calvi, Corsica

- 4th Foreign Regiment (4èmeRE), based in Castelnaudary (training), France

- Foreign Legion Recruiting Group (G.R.L.E), based at Fort de Nogent (military recruiting and other), France

- 13th Demi-Brigade of the Foreign Legion (13ème DBLE) stationed in Djibouti until 2011, then the United Arab Emirates until 2016. As of January 2016, the 13e DBLE is progressively based at Camp Larzac to integrate the 6e BLB

- French Overseas Territories and Overseas Collectives, France

- 3rd Foreign Infantry Regiment (3ème REI), based in French Guiana

- Foreign Legion Detachment in Mayotte (DLEM)

Current deployments

These are the following deployments:[52]

Note: English names for countries or territories are in parentheses.

- Opérations extérieures (other than at home bases or on standard duties)

- Guyane (French Guiana) Mission de presence sur l'Oyapok – Protection – 3ème REI Protection CSG ; 2ème REP / CEA; 2ème REI / 4ème compagnie

- Afghanistan Intervention 1er REC / 3° escadron (1 peloton); 2ème REI / 4° compagnie OMLT; 2ème REG / 1ère compagnie

- Mayotte (Departmental Collectivity of Mayotte) Prevention DLEM Mission de souveraineté

- Gabon Prevention 2ème REP / 3ème compagnie – 4ème compagnie

| Acronym | French Name | English Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| CEA | Compagnie d'éclairage et d'appuis | Reconnaissance and Support Company |

| CAC | Compagnie anti-char | Anti-Tank Company |

| UCL | Unité de commandement et de logistique | Unit of Command and Logistics |

| EMT | État-major tactique | Tactical Command Post |

| NEDEX | Neutralisation des explosifs | Neutralisation and Destruction of Explosives |

| OMLT | Operational Mentoring and Liaison Team (The official name for this branch is in English) | |

- ERC 90 light tank of the 13th Demi-Brigade of the Foreign Legion (13èmeDBLE) in Djibouti

- Paratroopers of 2ème REP in Djibouti

Snipers of the 2nd Foreign Infantry Regiment (2èmeREI) using a PGM Hécate and a FR-F2 in Afghanistan in 2005

Snipers of the 2nd Foreign Infantry Regiment (2èmeREI) using a PGM Hécate and a FR-F2 in Afghanistan in 2005 Legionnaire of 2ème REI with an M2 heavy machine gun

Legionnaire of 2ème REI with an M2 heavy machine gun- Legionnaire using an FR F2 in Afghanistan (2007)

DINOPS, PCG and Commandos

- 2ème REP Commando Parachute Group (GCP); Pathfinders qualified in Direct Actions, Special Recco and IMEX.

- 1st Foreign Engineer Regiment 1er REG; Parachute Underwater Demolition P.C.G Teams (Combat Engineer Divers, French: Plongeurs Commando group), DINOPS Teams of Nautical Subaquatic Intervention Operational Detachment (French: Détachement d'Intervention Nautique Operationnelle Subaquatique).

- 2nd Foreign Engineer Regiment 2ème REG; Parachute Underwater Demolition P.C.G Teams (Combat Engineer Divers, French: Plongeurs du Combat du Génie), DINOPS Teams of Nautical Subaquatic Intervention Operational Detachment (French: Détachement d'Intervention Nautique Operationnelle Subaquatique) and Mountain Commando Group (GCM) in some cases as double specialties.[53]

Recruitment process

| Arrival | 1 to 3 days in a Foreign Legion Information Center. Reception, information, and terms of contract. Afterwards transferred to Paris, Foreign Legion Recruitment Center. |

| Pre-selection | 1 to 4 days in a Foreign Legion Recruitment Center (Paris). Confirmation of motivation, initial medical check-up, finalising enlistment papers and signing of 5-year service contract. |

| Selection | 7 to 30 days in the Recruitment and Selection Center in Aubagne. Psychological and personality tests, logic tests (no education requirements), medical exam, physical condition tests, motivation and security interviews. Confirmation or denial of selection. |

| Passed Selection | Signing and handing-over of the five-year service contract. Incorporation into the Foreign Legion as a trainee. |

Basic training

While all rank and file members of the Legion are required to serve under "Foreign Status" (à titre étranger), even if they are French nationals, non-commissioned and commissioned officers can serve under either French or Foreign Status. Foreign Status NCOs and officers are exclusively promoted from the ranks and in 2016 represented 10% of the Officer Corps of the Legion.[54]. French Status officers are either members of other units of the French Army affected to the Legion or promoted Légionnaires who have chosen to become French nationals.

Basic training for the Foreign Legion is conducted in the 4th Foreign Regiment. This is an operational combat regiment which provides a training course of 15–17 weeks, before recruits are assigned to their operational units:

- Initial training of 4–6 weeks at The Farm (La Ferme) – introduction to military lifestyle; outdoor and field activities.

- March (Marche Képi Blanc) – a 50-kilometer (31 mi) two-day march (25 km per day) in full kit, followed by the Kepi Blanc ceremony on the 3rd day.

- Technical and practical training (alternating with barracks and field training) – three weeks.

- Mountain training (Chalet at Formiguière in the French Pyrenees) – one week.

- Technical and practical training (alternating barracks and field training) – three weeks.

- Examinations and obtaining of the elementary technical certificate (CTE) – one week.

- March (Raid Marche) – a 120-kilometer (75 mi) final march, which must be completed in three days.

- Light vehicle drivers education (drivers license) – one week.

- Return to Aubagne before reporting to the assigned operational regiment – one week.

Education in the French language (reading, writing and pronunciation) is taught on a daily basis throughout all of basic training.

- Legionnaires at Mayotte.

Legionnaires HALO jump from a C-160.

Legionnaires HALO jump from a C-160.- Legionnaires parachute from a C-160 while training at Camp Raffalli in Corsica.

Traditions

As the Foreign Legion is composed of soldiers of different nationalities and backgrounds, it needed to develop an intense esprit de corps,[43] which is achieved through the development of camaraderie,[43] specific traditions, the loyalty of its legionnaires, the quality of their training, and the pride of being a soldier in an élite unit.[43]

Code of honour

The "Legionnaire's Code of Honour"[55][56] is the Legion's creed, recited in French only.[57][58] The Code of Honour was adopted in the 1980s.[55]

| Code d'honneur du légionnaire | Legionnaire's Code of Honour | |

|---|---|---|

| Art. 1 | Légionnaire, tu es un volontaire, servant la France avec honneur et fidélité. | Legionnaire, you are a volunteer serving France with honour and fidelity. |

| Art. 2 | Chaque légionnaire est ton frère d'armes, quelle que soit sa nationalité, sa race ou sa religion. Tu lui manifestes toujours la solidarité étroite qui doit unir les membres d'une même famille. | Each legionnaire is your brother in arms whatever his nationality, his race or his religion might be. You show him the same close solidarity that links the members of the same family. |

| Art. 3 | Respectueux des traditions, attaché à tes chefs, la discipline et la camaraderie sont ta force, le courage et la loyauté tes vertus. | Respect for traditions, devotion to your leaders, discipline and comradeship are your strengths, courage and loyalty your virtues. |

| Art. 4 | Fier de ton état de légionnaire, tu le montres dans ta tenue toujours élégante, ton comportement toujours digne mais modeste, ton casernement toujours net. | Proud of your status as legionnaire, you display this in your always impeccable uniform, your always dignified but modest behaviour, and your clean living quarters. |

| Art. 5 | Soldat d'élite, tu t’entraînes avec rigueur, tu entretiens ton arme comme ton bien le plus précieux, tu as le souci constant de ta forme physique. | An elite soldier, you train rigorously, you maintain your weapon as your most precious possession, and you take constant care of your physical form. |

| Art. 6 | La mission est sacrée, tu l'exécutes jusqu’au bout et, s'il le faut, en opérations, au péril de ta vie. | The mission is sacred, you carry it out until the end and, if necessary in the field, at the risk of your life. |

| Art. 7 | Au combat, tu agis sans passion et sans haine, tu respectes les ennemis vaincus, tu n’abandonnes jamais ni tes morts, ni tes blessés, ni tes armes. | In combat, you act without passion and without hate, you respect defeated enemies, and you never abandon your dead, your wounded, or your arms. |

Mottos

Honneur et Fidélité

In contrast to all other French Army units, the motto embroidered on the Foreign Legion's regimental flags is not Honneur et Patrie (Honour and Fatherland) but Honneur et Fidélité (Honour and Fidelity).[59]

Legio Patria Nostra

Legio Patria Nostra (in French La Légion est notre Patrie, in English The Legion is our Fatherland) is the Latin motto of the Foreign Legion.[59] The adoption of the Foreign Legion as a new "fatherland" does not imply the repudiation by the legionnaire of his original nationality. The Foreign Legion is required to obtain the agreement of any legionnaire before he is placed in any situation where he might have to serve against his country of birth.

Regimental mottos

- 1er R.E: Honneur et Fidélité

- G.R.L.E: Honneur et Fidélité

- 1er REC: Honneur et Fidélité and Nec Pluribus Impar (No other equal)

- 2e REP: Honneur et Fidélité and More Majorum[60] (in the manner, ways and traditions of our veterans[61] foreign regiments)

- 2e REI: Honneur et Fidélité and Être prêt (Be ready)

- 2e REG: Honneur et Fidélité and Rien n'empêche (Nothing prevents)

- 3e REI: Honneur et Fidélité and Legio Patria Nostra

- 4e R.E: Honneur et Fidélité and Creuset de la Légion et Régiment des fortes têtes (The crucible of the Legion and the strong right minded regiment)

- 6e R.E.G then 1e REG: Honneur et Fidélité and Ad Unum (All to one end – for the regiment until the last one)

- 13e DBLE: Honneur et Fidélité and More Majorum[60] ("in the manner, ways and traditions of our veterans foreign regiments")

- DLEM: Honneur et Fidélité and Pericula Ludus (Dangers game – for the regiment To Danger is my pleasure of the 2nd Foreign Cavalry Regiment)

Insignia

Marching songs

Le Boudin

"Le Boudin"[5][64] is the marching song of the Foreign Legion.

Other songs

- "Non, Je Ne Regrette Rien", 1st Foreign Parachute Regiment

- "Sous Le Ciel de Paris", The Choir of the French Foreign Legion

- "Anne Marie du 3e" REI (in German)[65]

- "Adieu, adieu"

- "Aux légionnaires"

- "Anne Marie du 2e REI"[66]

- "Adieu vieille Europe"

- "Chant de l'Oignon"

- "Chant du quatrième escadron"

- "Chez nous au 3e"

- "C'est le 4"

- "Connaissez-vous ces hommes"

- "Contre les Viêts" (song of the 13th Demi-Brigade of the Foreign Legion after having been the marching song adopted by the 1st Foreign Parachute Regiment)

- "Cravate verte et Képi blanc"

- "Dans la brume, la rocaille"

- "Défilé du 3e REI"

- "C'était un Edelweiss"

- "Écho"

- "En Afrique"

- "En Algérie" (1er RE)[67]

- "Es steht eine Mühle" (in German)

- "Eugénie"

- "Les Képis Blancs" (1e RE)[68]

- "Honneur, Fidélité"

- "Ich hatt' einen Kameraden" (in German)

- "Il est un moulin"

- "J'avais un camarade"

- "Kameraden (in German)"

- "La colonne" (1er REC)

- "La Légion marche" (2e REP)[45]

- "La lune est claire"

- "Le Caïd"

- "Il y a des cailloux sur toutes les routes"

- "Le fanion de la Légion"

- "Le Soleil brille"

- "Le front haut et l'âme fière" (5e RE)

- "Légionnaire de l'Afrique"

- "Massari Marie"

- "Monica"

- "Sous le Soleil brûlant d'Afrique" (13e DBLE)

- "Nous sommes tous des volontaires" (1er RE)[69]

- "Nous sommes de la Légion"

- "La petite piste"

- "Pour faire un vrai légionnaire"

- "Premier chant du 1er REC"

- "Quand on an une fille dans l'cuir"

- "Rien n'empêche" (2er REG)[70]

- "Sapeur, mineurs et bâtisseurs" (6e REG)

- "Soldats de la Légion étrangère"

- "Souvenirs qui passe"

- "Suzanna"

- "The Windmill"

- "Venu volontaire"

- "Véronica"

Ranks

All volunteers in the French Foreign Legion begin their careers as basic legionnaires with one in four eventually becoming a sous-officier (non-commissioned officer). On joining, a new recruit receives a monthly salary of €1,200 in addition to food and lodgings.[9][71] He is also given his own new rifle, which according to the lore of the Legion must never be left on a battlefield.[9] Promotion is concurrent with the ranks in the French Army.

| Foreign Legion rank | Equivalent rank | NATO Code | Period of service | Insignia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engagé Volontaire | Recruit | – | 15 weeks basic training. | None |

| Legionnaire 2e Classe | Private / 2nd Class Legionnaire | OR-1 | On completion of training and Marche képi blanc (March of the White Kepi). | None |

| Legionnaire 1e Classe | Private / 1st Class Legionnaire | OR-2 | After 10 months of service. | |

| Caporal | Corporal | OR-3 | Possible after 1-year of service, known as the Fonctionnaire Caporal (or Caporal "Fut Fut") course. Recruits selected for this course need to show good leadership skills during basic training. | |

| Caporal Chef | Senior Corporal | OR-4 | After 6 years of service. | |

| Table note: Command insignia in the Foreign Legion use gold lace or braid indicating foot troops in the French Army. But the Légion étrangère service color is green (for the now-defunct colonial Armée d'Afrique) instead of red (regular infantry). | ||||

- A Caporal-chef Pionniers de la Légion of the 1st Foreign Regiment. The pionniers insigna depicts 2 crossed axes, instead of a grenade for the regular infantry.[72]

Non-Commissioned and Warrant Officers

The insignia for a Sous-officier contains three components. In this case, three upward gold chevrons indicates a Sergent-chef. The diamond-shaped regimental patch (or Écusson) is created from three green borders indicating a Colonial unit; rather than one for "Regulars" or two for "Reserves". The grenade has seven flames rather than the usual five. Two downward chevrons of seniority attests to at least 10 years service. Some Caporal-Chefs have as much as 6 "chevrons of seniority" attesting to 30 years (plus) of service.

Sous-officiers (NCOs) including warrant officers account for 25% of the current Foreign Legion's total manpower.

| Foreign Legion rank | Equivalent rank | NATO Code | Period of service | Insignia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sergent | Sergeant | OR-5 | After 3 years of service as Caporal. | |

| Sergent Chef | Senior Sergeant | OR-6 | After 3 years as Sergent and between 7 and 14 years of service. | |

| Adjudant | Warrant Officer | OR-8 | After 3 years as Sergent Chef. | |

| Adjudant Chef[lower-alpha 1] | Chief Warrant Officer | OR-9 | After 4 years as Adjudant and at least 14 years service. | |

| Major[lower-alpha 2] | Major[74] | OR-9 | Appointment by either: (i) passing an examination or (ii) promotion after a minimum of 14 years service (without an examination). |

|

| ||||

Commissioned Officers

Most officers are seconded from the French Army though roughly 10% are former non-commissioned officers promoted from the ranks.

| Foreign Legion rank | Equivalent rank | NATO Code | Command responsibility | Insignia |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sous-Lieutenant | Second lieutenant | OF-1 | Junior section leader | |

| Lieutenant | First lieutenant | OF-1 | A platoon. | |

| Capitaine | Captain | OF-2 | A company. | |

| Commandant | Major | OF-3 | A battalion. | |

| Lieutenant-Colonel | Lieutenant colonel | OF-4 | Junior régiment or demi-brigade leader. | |

| Colonel | Colonel | OF-5 | A régiment or demi-brigade. | |

| Général de brigade | Brigadier General | OF-6 | Brigade comprising régiments or demi-brigades. | |

| Le Commandement de la Légion étrangère[75] (Général de division) |

Général de division | OF-7 | Entire division or Army Corps of the French Foreign Legion |

Chevrons of seniority

The Foreign Legion still uses chevrons to indicate seniority (chevrons d'ancienneté). Each gold chevron, which are only worn by ordinary legionnaires and non-commissioned officers, denotes five years service in the Legion. They are worn beneath the rank insignia.[76]

Honorary ranks

The French Army had awarded honorary ranks to individuals credited with exceptional acts of courage since 1796.

In the Foreign Legion, General Paul-Frédéric Rollet introduced the practice of awarding of honorary Legion ranks to distinguished individuals, both civilian and military; men and women in the early 20th century. Recipients of these honorary appointments had participated in an exemplary manner on active service with units of the Legion, or had rendered exceptional service to the Legion in non-combat situations.[77]

More than 1,200 individuals have been granted honorary ranks in the Legion pour services éminent. The majority of these awards have been made to military personnel in wartime, earning titles such as Legionnaire d'Honneur or Sergent-Chef de Légion d'honneur. But other recipients have included nurses, journalists, painters, and ministers who have rendered meritorious service to the Foreign Legion.[77]

Pioneers

The Pionniers (pioneers) are the combat engineers and a traditional unit of the Foreign Legion. The sapper traditionally sport large beards, wear leather aprons and gloves and hold axes. The sappers were very common in European armies during the Napoleonic Era but progressively disappeared during the 19th century. The French Army, including the Legion disbanded its regimental sapper platoons in 1870. However, in 1931 one of a number of traditions restored to mark the hundredth anniversary of the Legion's founding was the reestablishment of its bearded Pionniers.[78]

In the French Army, since the 18th century, every infantry regiment included a small detachment of pioneers. In addition to undertaking road building and entrenchment work, such units were tasked with using their axes and shovels to clear obstacles under enemy fire opening the way for the rest of the infantry. The danger of such missions was recognised by allowing certain privileges, such as being authorised to wear beards.

The current pioneer platoon of the Foreign Legion is provided by the Legion depot and headquarters regiment for public ceremonies.[79] The unit has reintroduced the symbols of the Napoleonic sappers: the beard, the axe, the leather apron, the crossed-axes insignia and the leather gloves. When parades of the Foreign Legion are opened by this unit, it is to commemorate the traditional role of the sappers "opening the way" for the troops.[78]

Cadences and marching steps

Also notable is the marching pace of the Foreign Legion. In comparison to the 116-step-per-minute pace of other French units, the Foreign Legion has an 88-step-per-minute marching speed. It is also referred to by Legionnaires as the "crawl". This can be seen at ceremonial parades and public displays attended by the Foreign Legion, particularly while parading in Paris on 14 July (Bastille Day Military Parade). Because of the impressively slow pace, the Foreign Legion is always the last unit marching in any parade. The Foreign Legion is normally accompanied by its own band, which traditionally plays the march of any one of the regiments comprising the Foreign Legion, except that of the unit actually on parade. The regimental song of each unit and "Le Boudin" is sung by legionnaires standing at attention. Also, because the Foreign Legion must always stay together, it does not break formation into two when approaching the presidential grandstand, as other French military units do, in order to preserve the unity of the legion.

Contrary to popular belief, the adoption of the Foreign Legion's slow marching speed was not due to a need to preserve energy and fluids during long marches under the hot Algerian sun. Its exact origins are somewhat unclear, but the official explanation is that although the pace regulation does not seem to have been instituted before 1945, it hails back to the slow marching pace of the Ancien Régime, and its reintroduction was a "return to traditional roots".[80] This was in fact, the march step of the Foreign Legion's ancestor units – the Régiments Étrangers or Foreign Regiments of the Ancien Régime French Army, the Grande Armée's foreign units, and the pre-1831 foreign regiments.

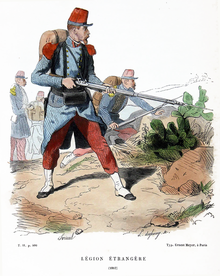

Uniform

From its foundation until World War I the Foreign Legion normally wore the uniform of the French line infantry for parade with a few special distinctions.[81] Essentially this consisted of a dark blue coat (later tunic) worn with red trousers. The field uniform was often modified under the influence of the extremes of climate and terrain in which the Foreign Legion served. Shakos were soon replaced by the light cloth kepi, which was far more suitable for North African conditions. The practice of wearing heavy capotes (greatcoats) on the march and vestes (short hip-length jackets) as working dress in barracks was followed by the Foreign Legion from its establishment.[82] One short lived aberration was the wearing of green uniforms in 1856 by Foreign Legion units recruited in Switzerland for service in the Crimean War.[83] In the Crimea itself (1854–59) a hooded coat and red or blue waist sashes were adopted for winter dress,[84] while during the Mexican Intervention (1863–65) straw hats or sombreros were sometimes substituted for the kepi.[85][86] When the latter was worn it was usually covered with a white "havelock" (linen cover) – the predecessor of the white kepi that was to become a symbol of the Foreign Legion. Foreign Legion units serving in France during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 were distinguishable only by minor details of insignia from the bulk of the French infantry. However subsequent colonial campaigns saw an increasing use of special garments for hot weather wear such as collarless keo blouses in Tonkin 1884–85, khaki drill jackets in Dahomey (1892)[87] and drab covered topees worn with all-white fatigue dress in Madagascar[88] (1895).[89]

In the early 20th century the legionnaire wore a red kepi with blue band and piping, dark blue tunic with red collar, red cuff patches, and red trousers.[90] Distinctive features were the green epaulettes (replacing the red of the line) worn with red woollen fringes;[91] plus the embroidered Legion badge of a red flaming grenade, worn on the kepi front instead of a regimental number.[92] In the field a light khaki cover was worn over the kepi, sometimes with a protective neck curtain attached. The standard medium-blue double breasted greatcoat (capote) of the French infantry was worn, usually buttoned back to free the legs for marching.[93] From the 1830s the legionnaires had worn a broad blue woollen sash around the waist,[94] like other European units of the French Army of Africa (such as the Zouaves or the Chasseurs d'Afrique), while indigenous units of the Army of Africa (spahis and tirailleurs) wore red sashes. White linen trousers tucked into short leather leggings were substituted for red serge in hot weather.[95] This was the origin of the "Beau Geste" image.

In barracks a white bleached kepi cover was often worn together with a short dark blue jacket ("veste") or white blouse plus white trousers. The original kepi cover was khaki and due to constant washing turned white quickly. The white or khaki kepi cover was not unique to the Foreign Legion at this stage but was commonly seen amongst other French units in North Africa. It later became particularly identified with the Foreign Legion as the unit most likely to serve at remote frontier posts (other than locally recruited tirailleurs who wore fezzes or turbans). The variances of climate in North Africa led the French Army to the sensible expedient of letting local commanders decide on the appropriate "tenue de jour" (uniform of the day) according to circumstances. Thus a legionnaire might parade or walk out in blue tunic and white trousers in hot weather, blue tunic and red trousers in normal temperatures or wear the blue greatcoat with red trousers under colder conditions. The sash could be worn with greatcoat, blouse or veste but not with the tunic. Epaulettes were a detachable dress item worn only with tunic or greatcoat for parade or off duty wear.[96]

Officers wore the same dark blue (almost black) tunics as those of their colleagues in the French line regiments, except that black replaced red as a facing colour on collar and cuffs.[97] Gold fringed epaulettes were worn for full dress and rank was shown by the number of gold rings on both kepi and cuffs. Trousers were red with black stripes or white according to occasion or conditions. All-white or light khaki uniforms (from as early as the 1890s) were often worn in the field or for ordinary duties in barracks.[98] Non-commissioned officers were distinguished by red or gold diagonal stripes on the lower sleeves of tunics, vestes and greatcoats.[99] Small detachable stripes were buttoned on to the front of the white shirt-like blouse.

Prior to 1914 units in Indo-China wore white or khaki Colonial Infantry uniforms with Foreign Legion insignia, to overcome supply difficulties.[100] This dress included a white sun helmet of a model that was also worn by Foreign Legion units serving in the outposts of Southern Algeria, though never popular with its wearers.[101] During the initial months of World War I, Foreign Legion units serving in France wore the standard blue greatcoat and red trousers of the French line infantry, distinguished only by collar patches of the same blue as the capote, instead of red.[102] After a short period in sky-blue the Foreign Legion adopted khaki with steel helmets, from early 1916. A mustard shade of khaki drill had been worn on active service in Morocco from 1909, replacing the classic blue and white.[103] The latter continued to be worn in the relatively peaceful conditions of Algeria throughout World War I, although increasingly replaced by khaki drill. The pre-1914 blue and red uniforms could still be occasionally seen as garrison dress in Algeria until stocks were used up about 1919.

During the early 1920s plain khaki drill uniforms of a standard pattern became universal issue for the Foreign Legion with only the red and blue kepi (with or without a cover) and green collar braiding to distinguish the Legionnaire from other French soldiers serving in North African and Indo-China. The neck curtain ceased to be worn from about 1915, although it survived in the newly raised Foreign Legion Cavalry Regiment into the 1920s. The white blouse (bourgeron) and trousers dating from 1882 were retained for fatigue wear until the 1930s.[104]

At the time of the Foreign Legion's centennial in 1931, a number of traditional features were reintroduced at the initiative of the then commander Colonel Rollet.[105] These included the blue sash and green/red epaulettes. In 1939 the white covered kepi won recognition as the official headdress of the Foreign Legion to be worn on most occasions, rather than simply as a means of reflecting heat and protecting the blue and red material underneath. The Third Foreign Infantry Regiment adopted white tunics and trousers for walking-out dress during the 1930s[106] and all Foreign Legion officers were required to obtain full dress uniforms in the pre-war colours of black and red from 1932 to 1939.

During World War II the Foreign Legion wore a wide range of uniform styles depending on supply sources. These ranged from the heavy capotes and Adrian helmets of 1940 through to British battledress and American field uniforms from 1943 to 1945. The white kepi was stubbornly retained whenever possible.

From 1940 until 1963 the Foreign Legion maintained four Saharan Companies (Compagnies Sahariennes) as part of the French forces used to patrol and police the desert regions to the south of Morocco and Algeria. Special uniforms were developed for these units, modeled on those of the French officered Camel Corps (Méharistes) having prime responsibility for the Sahara. In full dress these included black or white zouave style trousers, worn with white tunics and long flowing cloaks. The Legion companies maintained their separate identity by retaining their distinctive kepis, sashes and fringed epaulettes.

The white kepis, together with the sash[107] and epaulettes survive in the Foreign Legion's modern parade dress. Since the 1990s the modern kepi has been made wholly of white material rather than simply worn with a white cover. Officers and senior noncommissioned officers still wear their kepis in the pre-1939 colours of dark blue and red. A green tie and (for officers) a green waistcoat recall the traditional branch colour of the Foreign Legion. From 1959 a green beret (previously worn only by the legion's paratroopers) became the universal ordinary duty headdress, with the kepi reserved for parade and off duty wear.[108][109] Other items of currently worn dress are the standard issue of the French Army.

Equipment

The Foreign Legion is basically equipped with the same equipment as similar units elsewhere in the French Army. These include:

- The FAMAS assault rifle, a French-made automatic bullpup-style rifle, chambered in the 5.56×45mm NATO round. The FAMAS is being replaced by the Heckler & Koch HK416. The 13e DBLE, a Foreign Legion Regiment, was the first unit to use the new rifle.

- The SPECTRA is a ballistic helmet, designed by the French military, fitted with real-time positioning and information system, and with light amplifiers for night vision.

- The FÉLIN suit, an infantry combat system that combines ample pouches, reinforced body protections and a portable electronic platform.

Commandement de la Légion Étrangère Tenure (1931–present)

Commandement de la Légion Étrangère (1931–1984)

Inspector Tenure

Autonomous Group Tenure

Command Tenure

Technical Inspection Tenure

|

Groupment Tenure

Commandement de la Légion Étrangère (1984–present)Command Tenure

|

Gallery

Le Commandement de la Légion étrangère (1931–present)

Le Commandement de la Légion étrangère (1931–present)- French Foreign Legion headquarters in Aubagne.

White kepi (Képi blanc) of the French Foreign Legion

White kepi (Képi blanc) of the French Foreign Legion The FAMAS F1 is the standard issue rifle of the French Foreign Legion

The FAMAS F1 is the standard issue rifle of the French Foreign Legion Green beret (Béret vert) of the French Foreign Legion

Green beret (Béret vert) of the French Foreign Legion Second pattern beret cap badge, worn until 1990

Second pattern beret cap badge, worn until 1990- First pattern beret cap badge

Composition

The Foreign Legion is the only unit of the French Army open to people of any nationality. Most legionnaires still come from European countries but a growing percentage comes from Latin America.[110] Most of the Foreign Legion's commissioned officers are French with approximately 10 percent being Legionnaires who have risen through the ranks.[111]

Legionnaires were, in the past, forced to enlist under a pseudonym ("declared identity"). This policy existed in order to allow recruits who wanted to restart their lives to enlist. The Legion held the belief that it was fairer to make all new recruits use declared identities.[9] French citizens can enlist under a declared, fictitious, foreign citizenship (generally, a francophone one, often that of Belgium, Canada, or Switzerland). As of 20 September 2010, new recruits may enlist under their real identities or under declared identities. Recruits who do enlist with declared identities may, after one year's service, regularise their situations under their true identities.[112] After serving in the Foreign Legion for three years, a legionnaire may apply for French citizenship.[9] He must be serving under his real name, must have no problems with the authorities, and must have served with "honour and fidelity".[112] A soldier who becomes injured during a battle for France can immediately apply for French citizenship under a provision known as "Français par le sang versé" ("French by spilled blood").[9]

While the Foreign Legion historically did not accept women in its ranks, there was one official female member, Susan Travers, an Englishwoman who joined Free French Forces during World War II and became a member of the Foreign Legion after the war, serving in Vietnam during the First Indochina War.[113] Women were barred from service until 2000,[114] when then-French Defence Minister Alain Richard had stated that he wanted to take the level of female recruitment in the Legion to 20 percent by 2020.[115]

Membership by country

As of 2008, legionnaires came from 140 countries. The majority of enlisted men originate from outside France, while the majority of the officer corps consists of Frenchmen. Many recruits originate from Eastern Europe and Latin America. Neil Tweedie of The Daily Telegraph said that Germany traditionally provided many recruits, "somewhat ironically given the Legion's bloody role in two world wars."[9] He added that "Brits, too, have played their part, but there was embarrassment recently when it emerged that many British applicants were failing selection due to endemic unfitness."[9]

Alsace-Lorraine

Original nationalities of the Foreign Legion reflect the events in history at the time they join. Many former Wehrmacht personnel joined in the wake of World War II[116] as many soldiers returning to civilian life found it hard to find reliable employment. Jean-Denis Lepage reports that "The Foreign Legion discreetly recruited from German P.O.W. camps",[117] but adds that the number of these recruits has been subsequently exaggerated. Bernard B. Fall, who was a supporter of the French government, writing in the context of the First Indochina War, questioned the notion that the Foreign Legion was mainly German at that time, calling it:

[a] canard…with the sub-variant that all those Germans were at least SS generals and other much wanted war criminals. As a rule, and in order to prevent any particular nation from making the Foreign Legion into a Praetorian Guard, any particular national component is kept at about 25 percent of the total. Even supposing (and this was the case, of course) that the French recruiters, in the eagerness for candidates would sign up Germans enlisting as Swiss, Austrian, Scandinavian and other nationalities of related ethnic background, it is unlikely that the number of Germans in the Foreign Legion ever exceeded 35 percent. Thus, without making an allowance for losses, rotation, discharges, etc., the maximum number of Germans fighting in Indochina at any one time reached perhaps 7,000 out of 278,000. As to the ex-Nazis, the early arrivals contained a number of them, none of whom were known to be war criminals. French intelligence saw to that.

Since, in view of the rugged Indochinese climate, older men without previous tropical experience constituted more a liability than an asset, the average age of the Foreign Legion enlistees was about 23. At the time of the battle of Dien Bien Phu, any legionnaire of that age group was at the worst, in his "Hitler Youth" shorts when the [Third] Reich collapsed.[118]

The Foreign Legion accepts people enlisting under a nationality that is not their own. A proportion of the Swiss and Belgians are actually likely to be Frenchmen who wish to avoid detection.[119] In addition many Alsatians are said to have joined the Foreign Legion when Alsace was part of the German Empire, and may have been recorded as German while considering themselves French.

Regarding recruitment conditions within the Foreign Legion, see the official page (in English) dedicated to the subject:[120] With regard to age limits, recruits can be accepted from ages ranging from 17 ½ (with parental consent) to 39.5 years old.

Countries that allow post-Foreign Legion contract

In the Commonwealth Realms, its collective provisions provide for nationals to commute between armies in training or other purposes. Moreover, this 'blanket provision' between member-states cannot exclude others for it would seem inappropriate to single out individual countries, that is, France in relation to the Legion. For example, Australia and New Zealand may allow post-Legion enlistment providing the national has commonwealth citizenship. Britain allows post-Legion enlistment. Canada allows post-Legion enlistment in its ranks with a completed five-year contract.

In the European Union framework, post Legion enlistment is less clear. Denmark, Norway, Germany and Portugal allow post-Legion enlistment while The Netherlands has constitutional articles that forbid it. [Rijkswet op het Nederlanderschap, Artikel 15, lid 1e, (In Dutch:)[121]] (that is: one can lose his Dutch nationality by accepting a foreign nationality or can lose his Dutch nationality by serving in the army of a foreign state that is engaged in a conflict against the Dutch Kingdom or one of its allies[122]). The European Union twin threads seem to be recognized dual nationality status or restricting constitutional article.

The United States allows post-FFL enlistment in its National Guard of career soldiers (up to the rank of captain) who are Green Card holders.

Israel allows post-Legion enlistment.

One of the biggest national groups in the Legion are Poles. Polish law allows service in a foreign army, but only after written permission from the Ministry of National Defence.

Emulation by other countries

Chinese Ever Victorious Army

The Ever Victorious Army was the name given to a Chinese imperial army in the late 19th century. Commanded by Frederick Townsend Ward, the new force originally comprised about 200 mostly European mercenaries, recruited in the Shanghai area from sailors, deserters and adventurers. Many were dismissed in the summer of 1861, but the remainder became the officers of the Chinese soldiers recruited mainly in and around Sungkiang (Songjiang). The Chinese troops were increased to 3,000 by May 1862, all equipped with Western firearms and equipment by the British authorities in Shanghai. Throughout its four-year existence the Ever Victorious Army was mainly to operate within a thirty-mile radius of Shanghai. It was disbanded in May 1864 with 104 foreign officers and 2,288 Chinese soldiers being paid off. The bulk of the artillery and some infantry transferred to the Chinese Imperial forces. It was the first Chinese army trained in European techniques, tactics, and strategy.

Israeli Mahal

In Israel, Mahal (Hebrew: מח"ל, an acronym for Mitnadvei Ḥutz LaAretz, which means Volunteers from outside the Land [of Israel]) is a term designating non-Israelis serving in the Israeli military. The term originates with the approximately 4,000 both Jewish and non-Jewish volunteers who went to Israel to fight in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War including Aliyah Bet.[123] The original Mahalniks were mostly World War II veterans from American and British armed forces.

Today, there is a program, Garin Tzabar, within the Israeli Ministry of Defense that administers the enlistment of non-Israeli citizens in the country's armed forces. Programs enable foreigners to join the Israel Defense Forces if they are of Jewish descent (which is defined as at least one grandparent).

Netherlands KNIL Army

Though not named "Foreign Legion", the Dutch Koninklijk Nederlandsch-Indische Leger (KNIL), or Royal Netherlands-Indian Army (in reference to the Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia), was created in 1830, a year before the French Foreign Legion, and is therefore not an emulation but an entirely original idea and had a similar recruitment policy. It stopped being an army of foreigners around 1900 when recruitment was restricted to Dutch citizens and to the indigenous peoples of the Dutch East Indies. The KNIL was finally disbanded on 26 July 1950, seven months after the Netherlands formally recognised Indonesia as a sovereign state, and almost five years after Indonesia declared its independence.[124]

Rhodesian Light Infantry and 7 Independent Company