Education

Education is the process of facilitating learning, or the acquisition of knowledge, skills, values, beliefs, and habits. Educational methods include teaching, training, storytelling, discussion and directed research. Education frequently takes place under the guidance of educators, however learners can also educate themselves. Education can take place in formal or informal settings and any experience that has a formative effect on the way one thinks, feels, or acts may be considered educational. The methodology of teaching is called pedagogy.

Formal education is commonly divided formally into such stages as preschool or kindergarten, primary school, secondary school and then college, university, or apprenticeship.

A right to education has been recognized by some governments and the United Nations.[lower-alpha 1] In most regions, education is compulsory up to a certain age. There is a movement for education reform, and in particular for evidence-based education.

Etymology

Etymologically, the word "education" is derived from the Latin word ēducātiō ("A breeding, a bringing up, a rearing") from ēducō ("I educate, I train") which is related to the homonym ēdūcō ("I lead forth, I take out; I raise up, I erect") from ē- ("from, out of") and dūcō ("I lead, I conduct").[1]

History

-Old_City_Baku_Azerbaijan_1646.jpg)

Education began in prehistory, as adults trained the young in the knowledge and skills deemed necessary in their society. In pre-literate societies, this was achieved orally and through imitation. Story-telling passed knowledge, values, and skills from one generation to the next. As cultures began to extend their knowledge beyond skills that could be readily learned through imitation, formal education developed. Schools existed in Egypt at the time of the Middle Kingdom.[2]

Plato founded the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in Europe.[3] The city of Alexandria in Egypt, established in 330 BCE, became the successor to Athens as the intellectual cradle of Ancient Greece. There, the great Library of Alexandria was built in the 3rd century BCE. European civilizations suffered a collapse of literacy and organization following the fall of Rome in CE 476.[4]

In China, Confucius (551–479 BCE), of the State of Lu, was the country's most influential ancient philosopher, whose educational outlook continues to influence the societies of China and neighbours like Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. Confucius gathered disciples and searched in vain for a ruler who would adopt his ideals for good governance, but his Analects were written down by followers and have continued to influence education in East Asia into the modern era.[5]

The Aztecs also had a well-developed theory about education, which has an equivalent word in Nahuatl called tlacahuapahualiztli. It means "the art of raising or educating a person",[6] or "the art of strengthening or bringing up men".[7] This was a broad conceptualization of education, which prescribed that it begins at home, supported by formal schooling, and reinforced by community living. Historians cite that formal education was mandatory for everyone regardless of social class and gender.[8] There was also the word neixtlamachiliztli, which is "the act of giving wisdom to the face."[7] These concepts underscore a complex set of educational practices, which was oriented towards communicating to the next generation the experience and intellectual heritage of the past for the purpose of individual development and his integration into the community.[7]

After the Fall of Rome, the Catholic Church became the sole preserver of literate scholarship in Western Europe.[9] The church established cathedral schools in the Early Middle Ages as centres of advanced education. Some of these establishments ultimately evolved into medieval universities and forebears of many of Europe's modern universities.[4] During the High Middle Ages, Chartres Cathedral operated the famous and influential Chartres Cathedral School. The medieval universities of Western Christendom were well-integrated across all of Western Europe, encouraged freedom of inquiry, and produced a great variety of fine scholars and natural philosophers, including Thomas Aquinas of the University of Naples, Robert Grosseteste of the University of Oxford, an early expositor of a systematic method of scientific experimentation,[10] and Saint Albert the Great, a pioneer of biological field research.[11] Founded in 1088, the University of Bologne is considered the first, and the oldest continually operating university.[12]

Elsewhere during the Middle Ages, Islamic science and mathematics flourished under the Islamic caliphate which was established across the Middle East, extending from the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Indus in the east and to the Almoravid Dynasty and Mali Empire in the south.

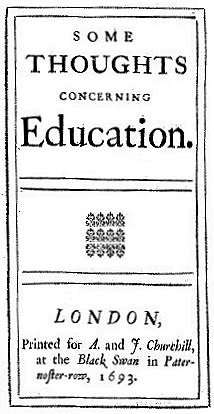

The Renaissance in Europe ushered in a new age of scientific and intellectual inquiry and appreciation of ancient Greek and Roman civilizations. Around 1450, Johannes Gutenberg developed a printing press, which allowed works of literature to spread more quickly. The European Age of Empires saw European ideas of education in philosophy, religion, arts and sciences spread out across the globe. Missionaries and scholars also brought back new ideas from other civilizations – as with the Jesuit China missions who played a significant role in the transmission of knowledge, science, and culture between China and Europe, translating works from Europe like Euclid's Elements for Chinese scholars and the thoughts of Confucius for European audiences. The Enlightenment saw the emergence of a more secular educational outlook in Europe.

In most countries today, full-time education, whether at school or otherwise, is compulsory for all children up to a certain age. Due to this the proliferation of compulsory education, combined with population growth, UNESCO has calculated that in the next 30 years more people will receive formal education than in all of human history thus far.[13]

Formal

Formal education occurs in a structured environment whose explicit purpose is teaching students. Usually, formal education takes place in a school environment with classrooms of multiple students learning together with a trained, certified teacher of the subject. Most school systems are designed around a set of values or ideals that govern all educational choices in that system. Such choices include curriculum, organizational models, design of the physical learning spaces (e.g. classrooms), student-teacher interactions, methods of assessment, class size, educational activities, and more.[14][15]

The International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) was created by UNESCO as a statistical base to compare education systems.[16] In 1997, it defined 7 levels of education and 25 fields, though the fields were later separated out to form a different project. The current version ISCED 2011 has 9 rather than 7 levels, created by dividing the tertiary pre-doctorate level into three levels. It also extended the lowest level (ISCED 0) to cover a new sub-category of early childhood educational development programmes, which target children below the age of 3 years.[17]

Early childhood

Education designed to support early development in preparation for participation in school and society. The programmes are designed for children below the age of 3. This is ISCED level 01.[16] Preschools provide education from ages approximately three to seven, depending on the country when children enter primary education. The children now readily interact with their peers and the educator.[16] These are also known as nursery schools and as kindergarten, except in the US, where the term kindergarten refers to the earliest levels of primary education.[18] Kindergarten "provides a child-centred, preschool curriculum for three- to seven-year-old children that aim[s] at unfolding the child's physical, intellectual, and moral nature with balanced emphasis on each of them."[19] This is ISCED level 02.[16]

Primary

This is ISCED level 1.[16] Primary (or elementary) education consists of the first four to seven years of formal, structured education. They are typically designed to provide young children with functional literacy and numeracy skills and to is guaranteed, solid foundation for most areas of knowledge and personal and social development to support the transition to secondary school.[20] In general, primary education consists of six to eight years of schooling starting at the age of five to seven, although this varies between, and sometimes within, countries. Globally, in 2008, around 89% of children aged six to twelve were enrolled in primary education, and this proportion was rising.[21] Under the Education For All programs driven by UNESCO, most countries have committed to achieving universal enrollment in primary education by 2015, and in many countries, it is compulsory. The division between primary and secondary education is somewhat arbitrary, but it generally occurs at about eleven or twelve years of age. Some education systems have separate middle schools, with the transition to the final stage of secondary education taking place at around the age of fifteen. Schools that provide primary education, are mostly referred to as primary schools or elementary schools. Primary schools are often subdivided into infant schools and junior school.

In India, for example, compulsory education spans over twelve years, with eight years of elementary education, five years of primary schooling and three years of upper primary schooling. Various states in the republic of India provide 12 years of compulsory school education based on a national curriculum framework designed by the National Council of Educational Research and Training.

Secondary

This covers the two ISCED levels, ISCED 2: Lower Secondary Education and ISCED 3: Upper Secondary Education.[16]

In most contemporary educational systems of the world, secondary education comprises the formal education that occurs during adolescence. In the United States, Canada, and Australia, primary and secondary education together are sometimes referred to as K-12 education, and in New Zealand Year 1–13 is used. The purpose of secondary education can be to give common knowledge, to prepare for higher education, or to train directly in a profession.

Secondary education in the United States did not emerge until 1910, with the rise of large corporations and advancing technology in factories, which required skilled workers. In order to meet this new job demand, high schools were created, with a curriculum focused on practical job skills that would better prepare students for white collar or skilled blue collar work. This proved beneficial for both employers and employees, since the improved human capital lowered costs for the employer, while skilled employees received higher wages.

Secondary education has a longer history in Europe, where grammar schools or academies date from as early as the 6th century, [lower-alpha 2] in the form of public schools, fee-paying schools, or charitable educational foundations, which themselves date even further back.

It spans the period between the typically universal compulsory, primary education to the optional, selective tertiary, "postsecondary", or "higher" education of ISCED 5 and 6 (e.g. university), and the ISCED 4 Further education or vocational school.[16]

Depending on the system, schools for this period, or a part of it, maybe called secondary or high schools, gymnasiums, lyceums, middle schools, colleges, or vocational schools. The exact meaning of any of these terms varies from one system to another. The exact boundary between primary and secondary education also varies from country to country and even within them but is generally around the seventh to the tenth year of schooling.

Lower

Programs at ISCED level 2, lower secondary education are usually organized around a more subject-oriented curriculum; differing from primary education. Teachers typically have pedagogical training in the specific subjects and, more often than at ISCED level 1, a class of students will have several teachers, each with specialized knowledge of the subjects they teach. Programmes at ISCED level 2, aim is to lay the foundation for lifelong learning and human development upon introducing theoretical concepts across a broad range of subjects which can be developed in future stages. Some education systems may offer vocational education programs during ISCED level 2 providing skills relevant to employment.[16]

Upper

Programs at ISCED level 3, or upper secondary education, are typically designed to complete the secondary education process. They lead to skills relevant to employment and the skill necessary to engage in tertiary courses. They offer students more varied, specialized and in-depth instruction. They are more differentiated, with range of options and learning streams.[16]

Community colleges offer another option at this transitional stage of education. They provide nonresidential junior college courses to people living in a particular area.

Tertiary

Higher education, also called tertiary, third stage, or postsecondary education, is the non-compulsory educational level that follows the completion of a school such as a high school or secondary school. Tertiary education is normally taken to include undergraduate and postgraduate education, as well as vocational education and training. Colleges and universities mainly provide tertiary education. Collectively, these are sometimes known as tertiary institutions. Individuals who complete tertiary education generally receive certificates, diplomas, or academic degrees.

The ISCED distinguishes 4 levels of tertiary education. ISCED 6 is equivalent to a first degree, ISCED 7 is equivalent to a masters or an advanced professional qualification and ISCED 8 is an advanced research qualification, usually concluding with the submission and defence of a substantive dissertation of publishable quality based on original research.[22] The category ISCED 5 is reserved for short-cycle courses of requiring degree level study.[22]

Higher education typically involves work towards a degree-level or foundation degree qualification. In most developed countries, a high proportion of the population (up to 50%) now enter higher education at some time in their lives. Higher education is therefore very important to national economies, both as a significant industry in its own right and as a source of trained and educated personnel for the rest of the economy.

University education includes teaching, research, and social services activities, and it includes both the undergraduate level (sometimes referred to as tertiary education) and the graduate (or postgraduate) level (sometimes referred to as graduate school). Some universities are composed of several colleges.

One type of university education is a liberal arts education, which can be defined as a "college or university curriculum aimed at imparting broad general knowledge and developing general intellectual capacities, in contrast to a professional, vocational, or technical curriculum."[23] Although what is known today as liberal arts education began in Europe,[24] the term "liberal arts college" is more commonly associated with institutions in the United States such as Williams College or Barnard College.[25]

Vocational

Vocational education is a form of education focused on direct and practical training for a specific trade or craft. Vocational education may come in the form of an apprenticeship or internship as well as institutions teaching courses such as carpentry, agriculture, engineering, medicine, architecture and the arts. Post 16 education, adult education and further education involve continued study, but a level no different from that found at upper secondary, and are grouped together as ISCED 4, post-secondary non-tertiary education.[22]

Special

In the past, those who were disabled were often not eligible for public education. Children with disabilities were repeatedly denied an education by physicians or special tutors. These early physicians (people like Itard, Seguin, Howe, Gallaudet) set the foundation for special education today. They focused on individualized instruction and functional skills. In its early years, special education was only provided to people with severe disabilities, but more recently it has been opened to anyone who has experienced difficulty learning.[26]

Other forms

Alternative

While considered "alternative" today, most alternative systems have existed since ancient times. After the public school system was widely developed beginning in the 19th century, some parents found reasons to be discontented with the new system. Alternative education developed in part as a reaction to perceived limitations and failings of traditional education. A broad range of educational approaches emerged, including alternative schools, self learning, homeschooling, and unschooling. Example alternative schools include Montessori schools, Waldorf schools (or Steiner schools), Friends schools, Sands School, Summerhill School, Walden's Path, The Peepal Grove School, Sudbury Valley School, Krishnamurti schools, and open classroom schools.

Charter schools are another example of alternative education, which have in the recent years grown in numbers in the US and gained greater importance in its public education system.[27][28]

In time, some ideas from these experiments and paradigm challenges may be adopted as the norm in education, just as Friedrich Fröbel's approach to early childhood education in 19th-century Germany has been incorporated into contemporary kindergarten classrooms. Other influential writers and thinkers have included the Swiss humanitarian Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi; the American transcendentalists Amos Bronson Alcott, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry David Thoreau; the founders of progressive education, John Dewey and Francis Parker; and educational pioneers such as Maria Montessori and Rudolf Steiner, and more recently John Caldwell Holt, Paul Goodman, Frederick Mayer, George Dennison, and Ivan Illich.

Indigenous

Indigenous education refers to the inclusion of indigenous knowledge, models, methods, and content within formal and non-formal educational systems. Often in a post-colonial context, the growing recognition and use of indigenous education methods can be a response to the erosion and loss of indigenous knowledge and language through the processes of colonialism. Furthermore, it can enable indigenous communities to "reclaim and revalue their languages and cultures, and in so doing, improve the educational success of indigenous students."[29]

Informal learning

Informal learning is one of three forms of learning defined by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Informal learning occurs in a variety of places, such as at home, work, and through daily interactions and shared relationships among members of society. For many learners, this includes language acquisition, cultural norms, and manners.

In informal learning, there is often a reference person, a peer or expert, to guide the learner. If learners have a personal interest in what they are informally being taught, learners tend to expand their existing knowledge and conceive new ideas about the topic being learned.[30] For example, a museum is traditionally considered an informal learning environment, as there is room for free choice, a diverse and potentially non-standardized range of topics, flexible structures, socially rich interaction, and no externally imposed assessments.[31]

While informal learning often takes place outside educational establishments and does not follow a specified curriculum, it can also occur within educational settings and even during formal learning situations. Educators can structure their lessons to directly utilize their students informal learning skills within the education setting.[30]

In the late 19th century, education through play began to be recognized as making an important contribution to child development.[32] In the early 20th century, the concept was broadened to include young adults but the emphasis was on physical activities.[33] L.P. Jacks, also an early proponent of lifelong learning, described education through recreation: "A master in the art of living draws no sharp distinction between his work and his play, his labour and his leisure, his mind and his body, his education and his recreation. He hardly knows which is which. He simply pursues his vision of excellence through whatever he is doing and leaves others to determine whether he is working or playing. To himself, he always seems to be doing both. Enough for him that he does it well."[34] Education through recreation is the opportunity to learn in a seamless fashion through all of life's activities.[35] The concept has been revived by the University of Western Ontario to teach anatomy to medical students.[35]

Self-directed learning

Autodidacticism (also autodidactism) is self-directed learning. One may become an autodidact at nearly any point in one's life. Notable autodidacts include Abraham Lincoln (U.S. president), Srinivasa Ramanujan (mathematician), Michael Faraday (chemist and physicist), Charles Darwin (naturalist), Thomas Alva Edison (inventor), Tadao Ando (architect), George Bernard Shaw (playwright), Frank Zappa (composer, recording engineer, film director), and Leonardo da Vinci (engineer, scientist, mathematician).

Evidence-based

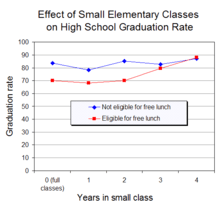

Evidence-based education is the use of well designed scientific studies to determine which education methods work best. It consists of evidence-based teaching and evidence-based learning. Evidence-based learning methods such as spaced repetition can increase rate of learning.[36] The evidence-based education movement has its roots in the larger movement towards evidence-based-practices.

Open learning and electronic technology

Many large university institutions are now starting to offer free or almost free full courses such as Harvard, MIT and Berkeley teaming up to form edX. Other universities offering open education are prestigious private universities such as Stanford, Princeton, Duke, Johns Hopkins, the University of Pennylvania, and Caltech, as well as notable public universities including Tsinghua, Peking, Edinburgh, University of Michigan, and University of Virginia.

Open education has been called the biggest change in the way people learn since the printing press.[37] Despite favourable studies on effectiveness, many people may still desire to choose traditional campus education for social and cultural reasons.[38]

Many open universities are working to have the ability to offer students standardized testing and traditional degrees and credentials.[39]

The conventional merit-system degree is currently not as common in open education as it is in campus universities, although some open universities do already offer conventional degrees such as the Open University in the United Kingdom. Presently, many of the major open education sources offer their own form of certificate. Due to the popularity of open education, these new kind of academic certificates are gaining more respect and equal "academic value" to traditional degrees.[40]

Out of 182 colleges surveyed in 2009 nearly half said tuition for online courses was higher than for campus-based ones.[41]

A recent meta-analysis found that online and blended educational approaches had better outcomes than methods that used solely face-to-face interaction.[42]

Public schooling

The education sector or education system is a group of institutions (ministries of education, local educational authorities, teacher training institutions, schools, universities, etc.) whose primary purpose is to provide education to children and young people in educational settings. It involves a wide range of people (curriculum developers, inspectors, school principals, teachers, school nurses, students, etc.). These institutions can vary according to different contexts.[43]

Schools deliver education, with support from the rest of the education system through various elements such as education policies and guidelines – to which school policies can refer – curricula and learning materials, as well as pre- and in-service teacher training programmes. The school environment – both physical (infrastructures) and psychological (school climate) – is also guided by school policies that should ensure the well-being of students when they are in school.[43] The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development has found that schools tend to perform best when principals have full authority and responsibility for ensuring that students are proficient in core subjects upon graduation. They must also seek feedback from students for quality-assurance and improvement. Governments should limit themselves to monitoring student proficiency.[44]

The education sector is fully integrated into society, through interactions with numerous stakeholders and other sectors. These include parents, local communities, religious leaders, NGOs, stakeholders involved in health, child protection, justice and law enforcement (police), media and political leadership.[43]

Development goals

Joseph Chimombo pointed out education's role as a policy instrument, capable of instilling social change and economic advancement in developing countries by giving communities the opportunity to take control of their destinies.[45] The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by the United Nations (UN) General Assembly in September 2015, calls for a new vision to address the environmental, social and economic concerns facing the world today. The Agenda includes 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 4 on education.[46][47]

Since 1909, the percentage of children in the developing world attending school has increased. Before then, a small minority of boys attended school. By the start of the twenty-first century, the majority of children in most regions of the world attended school.

Universal Primary Education is one of the eight international Millennium Development Goals, towards which progress has been made in the past decade, though barriers still remain.[48] Securing charitable funding from prospective donors is one particularly persistent problem. Researchers at the Overseas Development Institute have indicated that the main obstacles to funding for education include conflicting donor priorities, an immature aid architecture, and a lack of evidence and advocacy for the issue.[48] Additionally, Transparency International has identified corruption in the education sector as a major stumbling block to achieving Universal Primary Education in Africa.[49] Furthermore, demand in the developing world for improved educational access is not as high as foreigners have expected. Indigenous governments are reluctant to take on the ongoing costs involved. There is also economic pressure from some parents, who prefer their children to earn money in the short term rather than work towards the long-term benefits of education.

A study conducted by the UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning indicates that stronger capacities in educational planning and management may have an important spill-over effect on the system as a whole.[50] Sustainable capacity development requires complex interventions at the institutional, organizational and individual levels that could be based on some foundational principles:[50]

- national leadership and ownership should be the touchstone of any intervention;

- strategies must be context relevant and context specific;

- plans should employ an integrated set of complementary interventions, though implementation may need to proceed in steps;

- partners should commit to a long-term investment in capacity development while working towards some short-term achievements;

- outside intervention should be conditional on an impact assessment of national capacities at various levels;

- a certain percentage of students should be removed for improvisation of academics (usually practiced in schools, after 10th grade).

Internationalisation

Nearly every country now has universal primary education.

Similarities – in systems or even in ideas – that schools share internationally have led to an increase in international student exchanges. The European Socrates-Erasmus Programme[51] facilitates exchanges across European universities. The Soros Foundation[52] provides many opportunities for students from central Asia and eastern Europe. Programs such as the International Baccalaureate have contributed to the internationalization of education. The global campus online, led by American universities, allows free access to class materials and lecture files recorded during the actual classes.

The Programme for International Student Assessment and the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement objectively monitor and compare the proficiency of students from a wide range of different nations.

The internationalization of education is sometimes equated by critics with the westernization of education. These critics say that the internationalization of education leads to the erosion of local education systems and indigenous values and norms, which are replaced with Western systems and cultural and ideological values and orientation.[53]

Technology in developing countries

Technology plays an increasingly significant role in improving access to education for people living in impoverished areas and developing countries. However, lack of technological advancement is still causing barriers with regards to quality and access to education in developing countries.[54] Charities like One Laptop per Child are dedicated to providing infrastructures through which the disadvantaged may access educational materials.

The OLPC foundation, a group out of MIT Media Lab and supported by several major corporations, has a stated mission to develop a $100 laptop for delivering educational software. The laptops were widely available as of 2008. They are sold at cost or given away based on donations.

In Africa, the New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD) has launched an "e-school program" to provide all 600,000 primary and high schools with computer equipment, learning materials and internet access within 10 years.[55] An International Development Agency project called nabuur.com,[56] started with the support of former American President Bill Clinton, uses the Internet to allow co-operation by individuals on issues of social development.

India is developing technologies that will bypass land-based telephone and Internet infrastructure to deliver distance learning directly to its students. In 2004, the Indian Space Research Organisation launched EDUSAT, a communications satellite providing access to educational materials that can reach more of the country's population at a greatly reduced cost.[57]

Funding in developing countries

A survey of literature of the research into low-cost private schools (LCPS) found that over 5-year period to July 2013, debate around LCPSs to achieving Education for All (EFA) objectives was polarized and finding growing coverage in international policy.[58] The polarization was due to disputes around whether the schools are affordable for the poor, reach disadvantaged groups, provide quality education, support or undermine equality, and are financially sustainable. The report examined the main challenges encountered by development organizations which support LCPSs.[58] Surveys suggest these types of schools are expanding across Africa and Asia. This success is attributed to excess demand. These surveys found concern for:

- Equity: This concern is widely found in the literature, suggesting the growth in low-cost private schooling may be exacerbating or perpetuating already existing inequalities in developing countries, between urban and rural populations, lower- and higher-income families, and between girls and boys. The report findings suggest that girls may be under represented and that LCPS are reaching low-income families in smaller numbers than higher-income families.[58]

- Quality and educational outcomes: It is difficult to generalize about the quality of private schools. While most achieve better results than government counterparts, even after their social background is taken into account, some studies find the opposite. Quality in terms of levels of teacher absence, teaching activity, and pupil to teacher ratios in some countries are better in LCPSs than in government schools.[58]

- Choice and affordability for the poor: Parents can choose private schools because of perceptions of better-quality teaching and facilities, and an English language instruction preference. Nevertheless, the concept of 'choice' does not apply in all contexts, or to all groups in society, partly because of limited affordability (which excludes most of the poorest) and other forms of exclusion, related to caste or social status.[58]

- Cost-effectiveness and financial sustainability: There is evidence that private schools operate at low cost by keeping teacher salaries low, and their financial situation may be precarious where they are reliant on fees from low-income households.[58]

The report showed some cases of successful voucher where there was an oversupply of quality private places and an efficient administrative authority and of subsidy programs. Evaluations of the effectiveness of international support to the sector are rare.[58] Addressing regulatory ineffectiveness is a key challenge. Emerging approaches stress the importance of understanding the political economy of the market for LCPS, specifically how relationships of power and accountability between users, government, and private providers can produce better education outcomes for the poor.[58]

Theory

Psychology

Educational psychology is the study of how humans learn in educational settings, the effectiveness of educational interventions, the psychology of teaching, and the social psychology of schools as organizations. The terms "educational psychology" and "school psychology" are often used interchangeably. Educational psychology is concerned with the processes of educational attainment in the general population and in sub-populations such as gifted children and those with specific disabilities.

Educational psychology can in part be understood through its relationship with other disciplines. It is informed primarily by psychology, bearing a relationship to that discipline analogous to the relationship between medicine and biology. Educational psychology, in turn, informs a wide range of specialties within educational studies, including instructional design, educational technology, curriculum development, organizational learning, special education and classroom management. Educational psychology both draws from and contributes to cognitive science and the learning sciences. In universities, departments of educational psychology are usually housed within faculties of education, possibly accounting for the lack of representation of educational psychology content in introductory psychology textbooks (Lucas, Blazek, & Raley, 2006).

Psychological relationship

Intelligence is an important factor in how the individual responds to education. Those who have higher intelligence tend to perform better at school and go on to higher levels of education.[60] This effect is also observable in the opposite direction, in that education increases measurable intelligence.[61] Studies have shown that while educational attainment is important in predicting intelligence in later life, intelligence at 53 is more closely correlated to intelligence at 8 years old than to educational attainment.[62]

Learning modalities

There has been much interest in learning modalities and styles over the last two decades. The most commonly employed learning modalities are:[63]

- Visual: learning based on observation and seeing what is being learned.

- Auditory: learning based on listening to instructions/information.

- Kinesthetic: learning based on movement, e.g. hands-on work and engaging in activities.

Other commonly employed modalities include musical, interpersonal, verbal, logical, and intrapersonal.

Dunn and Dunn[64] focused on identifying relevant stimuli that may influence learning and manipulating the school environment, at about the same time as Joseph Renzulli[65] recommended varying teaching strategies. Howard Gardner[66] identified a wide range of modalities in his Multiple Intelligences theories. The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and Keirsey Temperament Sorter, based on the works of Jung,[67] focus on understanding how people's personality affects the way they interact personally, and how this affects the way individuals respond to each other within the learning environment. The work of David Kolb and Anthony Gregorc's Type Delineator[68] follows a similar but more simplified approach.

Some theories propose that all individuals benefit from a variety of learning modalities, while others suggest that individuals may have preferred learning styles, learning more easily through visual or kinesthetic experiences.[69] A consequence of the latter theory is that effective teaching should present a variety of teaching methods which cover all three learning modalities so that different students have equal opportunities to learn in a way that is effective for them.[70] Guy Claxton has questioned the extent that learning styles such as Visual, Auditory and Kinesthetic(VAK) are helpful, particularly as they can have a tendency to label children and therefore restrict learning.[71][72] Recent research has argued, "there is no adequate evidence base to justify incorporating learning styles assessments into general educational practice."[73]

Mind, brain, and education

Educational neuroscience is an emerging scientific field that brings together researchers in cognitive neuroscience, developmental cognitive neuroscience, educational psychology, educational technology, education theory and other related disciplines to explore the interactions between biological processes and education.[74][75][76][77] Researchers in educational neuroscience investigate the neural mechanisms of reading,[76] numerical cognition,[78] attention, and their attendant difficulties including dyslexia,[79][80] dyscalculia,[81] and ADHD as they relate to education. Several academic institutions around the world are beginning to devote resources to the establishment of educational neuroscience research.

Philosophy

As an academic field, philosophy of education is "the philosophical study of education and its problems its central subject matter is education, and its methods are those of philosophy".[82] "The philosophy of education may be either the philosophy of the process of education or the philosophy of the discipline of education. That is, it may be part of the discipline in the sense of being concerned with the aims, forms, methods, or results of the process of educating or being educated; or it may be metadisciplinary in the sense of being concerned with the concepts, aims, and methods of the discipline."[83] As such, it is both part of the field of education and a field of applied philosophy, drawing from fields of metaphysics, epistemology, axiology and the philosophical approaches (speculative, prescriptive or analytic) to address questions in and about pedagogy, education policy, and curriculum, as well as the process of learning, to name a few.[84] For example, it might study what constitutes upbringing and education, the values and norms revealed through upbringing and educational practices, the limits and legitimization of education as an academic discipline, and the relation between education theory and practice.

Purpose

There is no broad consensus as to what education's chief aim or aims are or should be. Different places, and at different times, have used educational systems for different purposes. The Prussian education system in the 19th century, for example, wanted to turn boys and girls into adults who would serve the state's political goals.[85][86]

Some authors stress its value to the individual, emphasizing its potential for positively influencing students' personal development, promoting autonomy, forming a cultural identity or establishing a career or occupation. Other authors emphasize education's contributions to societal purposes, including good citizenship, shaping students into productive members of society, thereby promoting society's general economic development, and preserving cultural values.[87]

The purpose of education in a given time and place affects who is taught, what is taught, and how the education system behaves. For example, in the 21st century, many countries treat education as a positional good.[88] In this competitive approach, people want their own students to get a better education than other students.[88] This approach can lead to unfair treatment of some students, especially those from disadvantaged or marginalized groups.[88] For example, in this system, a city's school system may draw school district boundaries so that nearly all the students in one school are from low-income families, and that nearly all the students in the neighboring schools come from more affluent families, even though concentrating low-income students in one school results in worse educational achievement for the entire school system.

Curriculum

In formal education, a curriculum is the set of courses and their content offered at a school or university. As an idea, curriculum stems from the Latin word for race course, referring to the course of deeds and experiences through which children grow to become mature adults. A curriculum is prescriptive and is based on a more general syllabus which merely specifies what topics must be understood and to what level to achieve a particular grade or standard.

An academic discipline is a branch of knowledge which is formally taught, either at the university – or via some other such method. Each discipline usually has several sub-disciplines or branches, and distinguishing lines are often both arbitrary and ambiguous. Examples of broad areas of academic disciplines include the natural sciences, mathematics, computer science, social sciences, humanities and applied sciences.[89]

Instruction

Instruction is the facilitation of another's learning. Instructors in primary and secondary institutions are often called teachers, and they direct the education of students and might draw on many subjects like reading, writing, mathematics, science and history. Instructors in post-secondary institutions might be called teachers, instructors, or professors, depending on the type of institution; and they primarily teach only their specific discipline. Studies from the United States suggest that the quality of teachers is the single most important factor affecting student performance, and that countries which score highly on international tests have multiple policies in place to ensure that the teachers they employ are as effective as possible.[90][91] With the passing of NCLB in the United States (No Child Left Behind), teachers must be highly qualified.

Economics

It has been argued that high rates of education are essential for countries to be able to achieve high levels of economic growth.[92] Empirical analyses tend to support the theoretical prediction that poor countries should grow faster than rich countries because they can adopt cutting-edge technologies already tried and tested by rich countries. However, technology transfer requires knowledgeable managers and engineers who are able to operate new machines or production practices borrowed from the leader in order to close the gap through imitation. Therefore, a country's ability to learn from the leader is a function of its stock of "human capital". Recent study of the determinants of aggregate economic growth have stressed the importance of fundamental economic institutions[93] and the role of cognitive skills.[94]

At the level of the individual, there is a large literature, generally related to the work of Jacob Mincer,[95] on how earnings are related to the schooling and other human capital. This work has motivated many studies, but is also controversial. The chief controversies revolve around how to interpret the impact of schooling.[96][97] Some students who have indicated a high potential for learning, by testing with a high intelligence quotient, may not achieve their full academic potential, due to financial difficulties.[98]

Economists Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis argued in 1976 that there was a fundamental conflict in American schooling between the egalitarian goal of democratic participation and the inequalities implied by the continued profitability of capitalist production.[99]

Future

The world is changing at an ever quickening rate, which means that a lot of knowledge becomes obsolete and inaccurate more quickly. The emphasis is therefore shifting to teaching the skills of learning: to picking up new knowledge quickly and in as agile a way as possible. Finnish schools have even begun to move away from the regular subject-focused curricula, introducing instead developments like phenomenon-based learning, where students study concepts like climate change instead.[100] There are also active educational interventions to implement programs and paths specific to non-traditional students, such as first generation students.

Education is also becoming a commodity no longer reserved for children. Adults need it too.[101] Some governmental bodies, like the Finnish Innovation Fund Sitra in Finland, have even proposed compulsory lifelong education.[102]

See also

- Education for Justice

- Alternative education

- Bildung

- Co-teaching

- Comprehensive sexuality education – Sex education instruction method

- Education for Sustainable Development

- Educational technology – Use of technology in education to improve learning and teaching

- Glossary of education terms

- Human rights education

- Index of education articles – Wikipedia index

- List of education articles by country – Wikipedia list article

- Mixed-sex education – System of education where males and females are educated together

- Outline of education – 1=Overview of and topical guide to education

- Pedagogy – Theory, and practice of education

- Progressive education

- Re-education

- Right to education

- Sociology of education

- Student – Learner, or someone who attends an educational institution

- School – Institution for the education of students by teachers

- School uniform

- Unschooling – Educational method and philosophy that rejects compulsory school as a primary means for learning

- Education in Islam

Notes

- Article 13 of the United Nations' 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights recognizes a universal right to education. ICESCR, Article 13.1.

- King's School Canterbury has been in continuous existence from 597 AD

- educate. Etymonline.com. Retrieved on 2011-10-21.

- Assmann 2002, p. 127.

- Lynch 1972, p. 47.

- Blainey 2004, p. ?.

- "Why Is Confucius Still Relevant Today? His Sound Bites Hold Up". nationalgeographic. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Colin 2014, p. 65.

- León-Portilla 2012, pp. 134–35.

- Reagan 2005, p. 108.

- "Science owes much to both Christianity and the Middle Ages: Soapbox Science". blogs.nature.com. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- "Robert Grosseteste". Catholic Encyclopedia. Newadvent. 1 June 1910. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- "St. Albertus Magnus". Catholic Encyclopedia. Newadvent.org. 1 March 1907. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- Sanz & Bergan 2006, p. 136.

- Robinson, K.: Schools Kill Creativity. TED Talks, 2006, Monterey, CA, US.

- "Enhancing Education". Archived from the original on 19 October 2003.

- "Perspectives Competence Centre, Lifeling Learning Programme". Archived from the original on 15 October 2014.

- ISCED 2011 classification

- Revision of the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED), retrieved 05-04-2012.

- "50-State Comparison: State Kindergarten-Through-Third-Grade Policies". www.ecs.org. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Ross, Elizabeth Dale (1976). The Kindergarten Crusade: The Establishment of Preschool in the United States. Athens: Ohio University Press. p. 1.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization “ISCED 2011”

- UNESCO, Education For All Monitoring Report 2008, Net Enrollment Rate in primary education

- "International Standard Classification of EducationI S C E D 1997". www.unesco.org. 11 April 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- "Liberal Arts: Britannica Concise Encyclopædia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 6 September 2007.

- Harriman, Philip (1935). "Antecedents of the Liberal Arts College". The Journal of Higher Education. 6 (2): 63–71. doi:10.2307/1975506. JSTOR 1975506.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Redden, Elizabeth (6 April 2009). "A Global Liberal Arts Alliance". Inside Higher Ed. Archived from the original on 9 April 2009. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- Special Education. Oxford: Elsevier Science and Technology. 2004.

- Lazarin, Melissa (October 2011). "Federal Investment in Charter Schools" (PDF). Institute of Education Sciences. Center for American Progress. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- Resmovits, Joy (10 December 2013). "Charter Schools Continue Dramatic Growth Despite Controversies". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- May, S.; Aikman, S. (2003). "Indigenous Education: Addressing Current Issues and Developments". Comparative Education. 39 (2): 139–45. doi:10.1080/03050060302549. JSTOR 3099875.

- Rogoff, Barbara; Callanan, Maureen; Gutiérrez, Kris D.; Erickson, Frederick (2016). "The Organization of Informal Learning". Review of Research in Education. 40: 356–401. doi:10.3102/0091732X16680994.

- Crowley, Kevin; Pierroux, Palmyre; Knutson, Karen (2014). Informal Learning in Museums. The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences. pp. 461–478. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139519526.028. ISBN 978-1-139-51952-6.

- Mead, GH (1896). "The Relation of Play to Education". University Record. 1: 141–45.

- Johnson, GE (1916). "Education through recreation". Cleveland Foundation, Ohio. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Jacks, LP (1932). Education through recreation. New York: Harper and Brothers. pp. 1–2.

- Ullah, Sha; Bodrogi, Andrew; Cristea, Octav; Johnson, Marjorie; McAlister, Vivian C. (2012). "Learning surgically oriented anatomy in a student-run extracurricular club: an education through recreation initiative". Anat Sci Educ. 5 (3): 165–70. doi:10.1002/ase.1273. PMID 22434649. Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- Smolen, Paul; Zhang, Yili; Byrne, John H. (25 January 2016). "The right time to learn: mechanisms and optimization of spaced learning". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 17 (2): 77–88. arXiv:1606.08370. doi:10.1038/nrn.2015.18. PMC 5126970. PMID 26806627.

- "Free courses provided by Harvard, MIT, Berkeley, Stanford, Princeton, Duke, Johns Hopkins, Edinburgh, U.Penn, U. Michigan, U. Virginia, U. Washington". Neurobonkers.com. 2 August 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- Harriet Swain (1 October 2012). "Will university campuses soon be 'over'?". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- Cloete, ElsabeÂ. "Electronic Education System Model." Department of Computer Science and Information Systems in South Africa, 17 October. 2000. Web. 3 June 2015.

- "Is the Certificate the New College Degree?". Good.is. 8 June 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- Parry, M. (2010). "Such a Deal? Maybe Not. Online learning can cost more than traditional education". The Chronicle of Higher Education. 57 (11).

- U.S. Department of Education, Evaluation of Evidence-Based Practices in Online Learning A Meta-Analysis and Review of Online Learning Studies, 2010

- UNESCO (2016). Out in the Open: Education sector responses to violence based on sexual orientation and gender identity/expression (PDF). Paris, UNESCO. p. 54. ISBN 978-92-3-100150-5.

- "School Governance, Assessments and Accountability" (PDF). Programme for International Student Assessment. OECD. 2013. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- Chimombo, Joseph (2005). "Issues in Basic Education in Developing Countries: An Exploration of Policy Options for Improved Delivery" (PDF). Journal of International Cooperation in Education. 8 (1): 129–152.

- Transforming our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals. New York: UN. 2016.

- Cracking the code: girls' and women's education in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). Paris: UNESCO. 2017. p. 14. ISBN 978-92-3-100233-5.

- Liesbet Steer and Geraldine Baudienville 2010. What drives donor financing of basic education? London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Addis Ababa (23 February 2010). "Poor governance jeopardises primary education in Africa". Transparency International. Archived from the original on 27 June 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- de Grauwe, A. (2009). Capacity development strategies (Report). Paris: UNESCO-IIPE. Archived from the original on 5 May 2010. Retrieved 1 October 2010..

- "Socrates-Erasmus Program". Erasmus.ac.uk. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- "Soros Foundation". Soros.org. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- Sperduti, Vanessa (2017). "Internationalization as Westernization in Higher Education" (PDF). Comparative & International Education 9 (2017). 9: 9–12. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- Aleed, Yasser (2016). "Effects of Education in Developing Countries". Journal of Construction in Developing Countries. December 2106.

- "African nations embrace e-learning, says new report". PC Advisor. 16 October 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- "nabuur.com". nabuur.com. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- "EDUSAT". ISRO. Archived from the original on 27 December 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- "Low-cost private schools: evidence, approaches and emerging issues". Eldis. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- Finn, J. D.; Gerber, S. B.; Boyd-Zaharias, J. (2005). "Small classes in the early grades, academic achievement, and graduating from high school" (PDF). Journal of Educational Psychology. 97 (2): 214–33. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.477.3560. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.97.2.214.

- Butler, S.; Marsh, H.; Sheppard, J. (1985). "Seven year longitudinal study of the early prediction of reading achievement". Journal of Educational Psychology. 77 (3): 349–61. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.77.3.349.

- Baltes, P.; Reinert, G. (1969). "Cohort effects in cognitive development in children as revealed by cross sectional sequences". Developmental Psychology. 1 (2): 169–77. doi:10.1037/h0026997.

- Richards, M.; Sacker, A. (2003). "Lifetime Antecedents of Cognitive Reserve". Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 25 (5): 614–24. doi:10.1076/jcen.25.5.614.14581. PMID 12815499.

- Swassing, R. H., Barbe, W. B., & Milone, M. N. (1979). The Swassing-Barbe Modality Index: Zaner-Bloser Modality Kit. Columbus, OH: Zaner-Bloser.

- "Dunn and Dunn". Learningstyles.net. Archived from the original on 3 February 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2009.

- "Biographer of Renzulli". Indiana.edu. Archived from the original on 7 September 2003. Retrieved 20 April 2009.

- Thomas Armstrong's website Archived 21 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine detailing Multiple Intelligences

- "Keirsey web-site". Keirsey.com. Retrieved 20 April 2009.

- "Type Delineator description". Algonquincollege.com. Archived from the original on 1 March 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2009.

- Barbe, W. B., & Swassing, R. H., with M. N. Milone. (1979). Teaching through modality strengths: Concepts and practices. Columbus, OH: Zaner-Bloser

- "Learning modality description from the Learning Curve website". Library.thinkquest.org. Archived from the original on 4 April 2008. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- "Guy Claxton speaking on What's The Point of School?". dystalk.com. Archived from the original on 21 May 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2009.

- J. Scott Armstrong (1983). "Learner Responsibility in Management Education, or Ventures into Forbidden Research (with Comments)" (PDF). Interfaces. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2010.

- Pashler, Harold; McDonald, Mark; Rohrer, Doug; Bjork, Robert (2009). "Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence" (PDF). Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 9 (3): 105–19. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6053.2009.01038.x. PMID 26162104.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ansari, D; Coch, D (2006). "Bridges over troubled waters: Education and cognitive neuroscience". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 10 (4): 146–51. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2006.02.007. PMID 16530462.

- Coch, D; Ansari, D (2008). "Thinking about mechanisms is crucial to connecting neuroscience and education". Cortex. 45 (4): 546–47. doi:10.1016/j.cortex.2008.06.001. PMID 18649878.

- Goswami, U (2006). "Neuroscience and education: from research to practice?". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 7 (5): 406–11. doi:10.1038/nrn1907. PMID 16607400.

- Meltzoff, AN; Kuhl, PK; Movellan, J; Sejnowski, TJ (2009). "Foundations for a New Science of Learning". Science. 325 (5938): 284–88. Bibcode:2009Sci...325..284M. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.165.1628. doi:10.1126/science.1175626. PMC 2776823. PMID 19608908.

- Ansari, D (2008). "Effects of development and enculturation on number representation in the brain". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 9 (4): 278–91. doi:10.1038/nrn2334. PMID 18334999.

- McCandliss, BD; Noble, KG (2003). "The development of reading impairment: a cognitive neuroscience model" (PDF). Mental Retardation and Developmental Disability Research Review. 9 (3): 196–204. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.587.4158. doi:10.1002/mrdd.10080. PMID 12953299. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- Gabrieli, JD (2009). "Dyslexia: a new synergy between education and cognitive neuroscience" (PDF). Science. 325 (5938): 280–83. Bibcode:2009Sci...325..280G. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.472.3997. doi:10.1126/science.1171999. PMID 19608907.

- Price, GR; Holloway, I; Räsänen, P; Vesterinen, M; Ansari, D (2007). "Impaired parietal magnitude processing in developmental dyscalculia". Current Biology. 17 (24): R1042–43. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.013. PMID 18088583.

- Noddings, Nel (1995). Philosophy of Education. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8133-8429-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Frankena, William K.; Raybeck, Nathan; Burbules, Nicholas (2002). "Philosophy of Education". In Guthrie, James W. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Education, 2nd edition. New York, NY: Macmillan Reference. ISBN 978-0-02-865594-9.

- Noddings 1995, pp. 1–6

- Clark, Christopher (6 September 2007). Iron Kingdom: The Rise and Downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-190402-3.

The emancipated citizens who emerged from every level of Humboldt's educational system were expected to take an active part in the political life of the Prussian state.

- Mommsen, Peter (Winter 2019). "The Community of Education". Plough Quarterly.

- Christopher Winch and John Gingell, Philosophy of Education: The Key Concepts (2nd edition). London:Routledge, 2008. pp. 10–11.

- Park, Hyunjoon; Shavit, Yossi, eds. (March 2016). "Special Issue: Education as a Positional Good". Research in Social Stratification and Mobility. 43 (supplement): 1–70. ISSN 0276-5624.

- "Examples of subjects". Curriculumonline.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 21 August 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2009.

- Winters, Marcus (2012). Teachers Matter: Rethinking How Public Schools Identify, Reward, and Retain Great Educators. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 160. ISBN 978-1-4422-1077-6.

- "How the world's best-performing school systems come out on top" (PDF). mckinsey.com. September 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011.

- Eric A. Hanushek (2005). Economic outcomes and school quality. International Institute for Educational Planning. ISBN 978-92-803-1279-9. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- Daron Acemoglu; Simon Johnson; James A. Robinson (2001). "The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation". American Economic Review. 91 (5): 1369–401. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.475.6366. doi:10.2139/ssrn.244582. JSTOR 2677930.

- Eric A. Hanushek; Ludger Woessmann (2008). "The role of cognitive skills in economic development" (PDF). Journal of Economic Literature. 46 (3): 607–08. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.507.5325. doi:10.1257/jel.46.3.607. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 January 2011.

- Jacob Mincer (1970). "The distribution of labor incomes: a survey with special reference to the human capital approach". Journal of Economic Literature. 8 (1): 1–26. JSTOR 2720384.

- David Card, "Causal effect of education on earnings," in Handbook of labor economics, Orley Ashenfelter and David Card (Eds). Amsterdam: North-Holland, 1999: pp. 1801–63

- James J. Heckman, Lance J. Lochner, and Petra E. Todd, "Earnings functions, rates of return and treatment effects: The Mincer equation and beyond," in Handbook of the Economics of Education, Eric A. Hanushek and Finis Welch (Eds). Amsterdam: North Holland, 2006: pp. 307–458.

- "Why a high IQ doesn't mean you're smart". Yale School of Management. 1 November 2009. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- Samuel Bowles; Herbert Gintis (2011). Schooling in Capitalist America: Educational Reform and the Contradictions of Economic Life. Haymarket Books. ISBN 978-1-60846-131-8.

- "Finnish National Agency for Education - Curricula 2014". www.oph.fi. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

- "For many people, flexibility at work can be a liberation".

- "Could compulsory education last a lifetime? - Sitra".

References

- Assmann, Jan (2003). The Mind of Egypt: History and Meaning in the Time of the Pharaohs. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01211-9.

- Blainey, Geoffrey (2004). A very short history of the world. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 0-7139-9822-9.

- Colin, Ernesto (2014). Indigenous Education through Dance and Ceremony: A Mexica Palimpsest. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-349-47094-5.

- León-Portilla, Miguel (2012). Aztec Thought and Culture: A Study of the Ancient Nahuatl Mind. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-0569-7.

- Lynch, John Patrick (1972). Aristotle's School; a Study of a Greek Educational Institution. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-02194-0.

- Reagan, Timothy (2005). Non-Western Educational Traditions: Alternative Approaches to Educational Thought and Practice. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8058-4857-1.

- Sanz, Nuria; Bergan, Sjur (1 January 2006). Le Patrimoine Des Universités Européennes [The Heritage of European Universities] (2nd ed.). Strasbourg: Council of Europe. ISBN 978-92-871-6121-5.

- Attribution

External links

- Education at the Encyclopædia Britannica

| Library resources about Education |

- Education at Curlie

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics: International comparable statistics on education systems

- World Bank Education

- Systems Approach for Better Education Results (SABER)

- Education Statistics (EdStats)

- OECD Education GPS: Statistics and policy analysis, interactive portal

- OECD Statistics

- IIEP Publications on Education Systems