Education in Bhutan

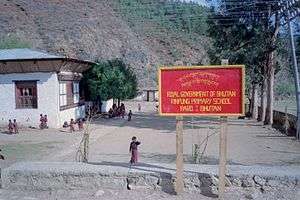

Western-style education was introduced to Bhutan during the reign of Ugyen Wangchuck (1907–26). Until the 1950s, the only formal education available to Bhutanese students, except for private schools in Ha and Bumthang, was through Buddhist monasteries. In the 1950s, several private secular schools were established without government support, and several others were established in major district towns with government backing. By the late 1950s, there were twenty-nine government and thirty private primary schools, but only about 2,500 children were enrolled. Secondary education was available only in India. Eventually, the private schools were taken under government supervision to raise the quality of education provided. Although some primary schools in remote areas had to be closed because of low attendance, the most significant modern developments in education came during the period of the First Development Plan (1961–66), when some 108 schools were operating and 15,000 students were enrolled (see Role of the Government, this ch.)

Five-Year Plans

The First Five-Year Plan provided for a central education authority—in the form of a director of education appointed in 1961—and an organized, modern school system with free and universal primary education. Since that time, following one year of preschool begun at age four, children attended school in the primary grades—one through five. Education continued with the equivalent of grades six through eight at the junior high level and grades nine through eleven at the high school level. The Department of Education administered the All-Bhutan Examinations nationwide to determine promotion from one level of schooling to the next. Examinations at the tenth-grade level were conducted by the Indian School Certificate Council. The Department of Education also was responsible for producing textbooks; preparing course syllabi and in-service training for teachers; arranging training and study abroad; organizing interschool tournaments; procuring foreign assistance for education programs; and recruiting, testing, and promoting teachers, among other duties.

The core curriculum set by the National Board of Secondary Education included English, mathematics, and Dzongkha. Although English was used as the language of instruction throughout the junior high and high school system, Dzongkha, and, in southern Bhutan until 1989, Nepali, were compulsory subjects. Students also studied English literature, social studies, history, geography, general science, biology, chemistry, physics, and religion. Curriculum development often has come from external forces, as was the case with historical studies. Most Bhutanese history is based on oral traditions rather than on written histories or administrative records. A project sponsored by UNESCO and the University of London developed a ten-module curriculum, which included four courses on Bhutanese history and culture and six courses on Indian and world history and political ideas. Subjects with an immediate practical application, such as elementary agriculture, animal husbandry, and forestry, also were taught.

Bhutan's coeducational school system in 1988 encompassed a reported 42,446 students and 1,513 teachers in 150 primary schools, 11,835 students and 447 teachers in 21 junior high schools, and 4,515 students and 248 teachers in 9 high schools. Males accounted for 63 percent of all primary and secondary students. Most teachers at these levels—70 percent—also were males. There also were 1,761 students and 150 teachers in technical, vocational, and special schools in 1988.

Despite increasing student enrollments, which went from 36,705 students in 1981 to 58,796 students in 1988, education was not compulsory. In 1988 only about 25 percent of primary-school-age children attended school, an extremely low percentage by all standards. Although the government set enrollment quotas for high schools, in no instance did they come close to being met in the 1980s. Only about 8 percent of junior high-school-age and less than 3 percent of high-school-age children were enrolled in 1988.

Bhutan's literacy rate in the early 1990s was estimated at 30 percent for males and 10 percent for females by the United Nations Development Programme, ranked lowest among all least developed countries. Other sources ranked the literacy rate as low as 12 to 18 percent. In 2015, the literacy rate was 59.5 percent.

.jpg)

Some primary schools and all junior high and high schools were boarding schools. The school year in the 1980s ran from March through December. Tuition, books, stationery, athletic equipment, and food were free for all boarding schools in the 1980s, and some high schools also provided clothing. With the assistance of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization's World Food Programme, free midday meals were provided in some primary schools.

Higher education was provided by Royal Bhutan Polytechnic just outside the village of Deothang, Samdrup Jongkhar District, and by Kharbandi Technical School in Kharbandi, Chhukha District. Founded in 1973, Royal Bhutan Polytechnic offered courses in civil, mechanical, and electrical engineering; surveying; and drafting. Kharbandi Technical School was established in the 1970s with UNDP and International Labour Organization assistance. Bhutan's only junior college--Sherubtse College in Kanglung, Trashigang District—was established in 1983 as a three-year degree-granting college affiliated with the University of Delhi. In the year it was established with UNDP assistance, the college enrolled 278 students, and seventeen faculty members taught courses in arts, sciences, and commerce leading to a bachelor's degree. Starting in 1990, junior college classes also were taught at the Yanchenphug High School in Thimphu and were to be extended to other high schools thereafter.

Education programs were given a boost in 1990 when the Asian Development Bank (see Glossary) granted a US$7.13 million loan for staff training and development, specialist services, equipment and furniture purchases, salaries and other recurrent costs, and facility rehabilitation and construction at Royal Bhutan Polytechnic. The Department of Education and its Technical and Vocational Education Division were given a US$750,000 Asian Development Bank grant for improving the technical, vocational, and training sectors. The New Approach to Primary Education, started in 1985, was extended to all primary and junior high schools in 1990 and stressed self-reliance and awareness of Bhutan's unique national culture and environment.

Most Bhutanese students being educated abroad received technical training in India, Singapore, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Britain, the Germany, and the United States. English-speaking countries attracted the majority of Bhutanese students. The vast majority returned to their homeland.

Women and education

The number of girls in Bhutan receiving an education is increasing however, women still fall behind men due to things such as early pregnancy and gender stereotypes.[1] Tertiary Education is a field in which Bhutanese women fall behind in, mainly due to high maternal mortality rates and early pregnancy.[1] However, the primary enrollment rate for girls attending school was 98.8%, compared to boys which was 97% in 2016.[2] This is due to the government increasing its investment in human capital in the last 30 years.[3]

Indian Teachers in Bhutan

Since the beginning of education in Bhutan, teachers from India, especially Kerala has served in some of the most remote villages of Bhutan. In honour to their service 43 retired teachers who served for long time in were invited to Thimphu, Bhutan during the teachers day celebrations in 2018 and individually thanked by His Majesty Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck. To celebrate 50 years of diplomatic relations between Bhutan and India, 80 teachers who served in Bhutan were honoured by the Education Minister Jai Bir Rai at a special ceremony organized at Kolkata, India on 6 January 2019.[4] Currently, there are 121 teachers from India placed in schools across Bhutan.

References

- "Bhutan Gains Ground on Gender Equality But Challenges Remain in Key Areas". The Asian Development Bank.

- Lhaden, Tenzin. "Moving towards Gender Equality in Bhutan".

- "Bhutan Gender Policy Note".

- http://www.bbs.bt/news/?p=109304

![]()