Walden

Walden (/ˈwɔːldən/; first published in 1854 as Walden; or, Life in the Woods) is a book by American transcendentalist writer Henry David Thoreau. The text is a reflection upon simple living in natural surroundings. The work is part personal declaration of independence, social experiment, voyage of spiritual discovery, satire, and—to some degree—a manual for self-reliance.[2]

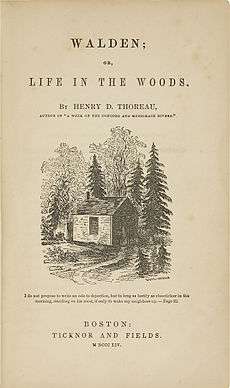

Original title page of Walden featuring a picture drawn by Thoreau's sister Sophia. | |

| Author | Henry David Thoreau |

|---|---|

| Original title | Walden; or, Life in the Woods |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Memoir |

| Published | August 9, 1854[1] (Ticknor and Fields: Boston) |

| Media type | |

Walden details Thoreau's experiences over the course of two years, two months, and two days in a cabin he built near Walden Pond amidst woodland owned by his friend and mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson, near Concord, Massachusetts. Thoreau used this time (July 4, 1845 – September 6, 1847) to write his first book, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849). The experience later inspired Walden, in which Thoreau compresses the time into a single calendar year and uses passages of four seasons to symbolize human development.

By immersing himself in nature, Thoreau hoped to gain a more objective understanding of society through personal introspection. Simple living and self-sufficiency were Thoreau's other goals, and the whole project was inspired by transcendentalist philosophy, a central theme of the American Romantic Period.

Thoreau makes precise scientific observations of nature as well as metaphorical and poetic uses of natural phenomena. He identifies many plants and animals by both their popular and scientific names, records in detail the color and clarity of different bodies of water, precisely dates and describes the freezing and thawing of the pond, and recounts his experiments to measure the depth and shape of the bottom of the supposedly "bottomless" Walden Pond.

Plot

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did I wish to practice resignation, unless it was quite necessary. I wanted to live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms, and, if it proved to be mean, why then to get the whole and genuine meanness of it, and publish its meanness to the world; or if it were sublime, to know it by experience, and be able to give a true account of it in my next excursion.

Part memoir and part spiritual quest, Walden opens with the announcement that Thoreau spent two years at Walden Pond living a simple life without support of any kind. Readers are reminded that at the time of publication, Thoreau is back to living among the civilized again. The book is separated into specific chapters, each of which focuses on specific themes:

Economy: In this first and longest chapter, Thoreau outlines his project: a two-year, two-month, and two-day stay at a cozy, "tightly shingled and plastered", English-style 10' × 15' cottage in the woods near Walden Pond.[4] He does this, he says, to illustrate the spiritual benefits of a simplified lifestyle. He easily supplies the four necessities of life (food, shelter, clothing, and fuel) with the help of family and friends, particularly his mother, his best friend, and Mr. and Mrs. Ralph Waldo Emerson. The latter provided Thoreau with a work exchange: he could build a small house and plant a garden if he cleared some land on the woodlot and did other chores while there.[4] Thoreau meticulously records his expenditures and earnings, demonstrating his understanding of "economy", as he builds his house and buys and grows food. For a home and freedom, he spent a mere $28.12½, in 1845 (about $934 in 2018 dollars). At the end of this chapter, Thoreau inserts a poem, "The Pretensions of Poverty", by seventeenth-century English poet Thomas Carew. The poem criticizes those who think that their poverty gives them unearned moral and intellectual superiority. Much attention is devoted to the skepticism and wonderment with which townspeople greeted both him and his project as he tries to protect his views from those of the townspeople who seem to view society as the only place to live. He recounts the reasons for his move to Walden Pond along with detailed steps back to the construction of his new home (methods, support, etc.).

Where I Lived, and What I Lived For: Thoreau recollects thoughts of places he stayed at before selecting Walden Pond, and quotes Roman Philosopher Cato's advice "consider buying a farm very carefully before signing the papers."[5] His possibilities included a nearby Hollowell farm (where the "wife" unexpectedly decided she wanted to keep the farm). Thoreau takes to the woods dreaming of an existence free of obligations and full of leisure. He announces that he resides far from social relationships that mail represents (post office) and the majority of the chapter focuses on his thoughts while constructing and living in his new home at Walden.[4]

Reading: Thoreau discusses the benefits of classical literature, preferably in the original Greek or Latin, and bemoans the lack of sophistication in Concord evident in the popularity of unsophisticated literature. He also loved to read books by world travelers.[6] He yearns for a time when each New England village supports "wise men" to educate and thereby ennoble the population.

Sounds: Thoreau encourages the reader to be "forever on the alert" and "looking always at what is to be seen."[5] Although truth can be found in literature, it can equally be found in nature. In addition to self-development, an advantage of developing one's perceptiveness is its tendency to alleviate boredom. Rather than "look abroad for amusement, to society and the theatre", Thoreau's own life, including supposedly dull pastimes like housework, becomes a source of amusement that "never ceases to be novel."[5] Likewise, he obtains pleasure in the sounds that ring around his cabin: church bells ringing, carriages rattling and rumbling, cows lowing, whip-poor-wills singing, owls hooting, frogs croaking, and cockerels crowing. "All sound heard at the greatest possible distance," he contends "produces one and the same effect."[5] Likening the train's cloud of steam to a comet tail and its commotion to "the scream of a hawk", the train becomes homologous with nature and Thoreau praises its associated commerce for its enterprise, bravery, and cosmopolitanism, proclaiming: "I watch the passage of the morning cars with the same feeling that I do the rising of the sun."[5]

Solitude: Thoreau reflects on the feeling of solitude. He explains how loneliness can occur even amid companions if one's heart is not open to them. Thoreau meditates on the pleasures of escaping society and the petty things that society entails (gossip, fights, etc.). He also reflects on his new companion, an old settler who arrives nearby and an old woman with great memory ("memory runs back farther than mythology").[7] Thoreau repeatedly reflects on the benefits of nature and of his deep communion with it and states that the only "medicine he needs is a draught of morning air".[5]

Visitors: Thoreau talks about how he enjoys companionship (despite his love for solitude) and always leaves three chairs ready for visitors. The entire chapter focuses on the coming and going of visitors, and how he has more comers in Walden than he did in the city. He receives visits from those living or working nearby and gives special attention to a French Canadian born woodsman named Alec Thérien. Unlike Thoreau, Thérien cannot read or write and is described as leading an "animal life". He compares Thérien to Walden Pond itself. Thoreau then reflects on the women and children who seem to enjoy the pond more than men, and how men are limited because their lives are taken up.

The Bean-Field: Reflection on Thoreau's planting and his enjoyment of this new job/hobby. He touches upon the joys of his environment, the sights and sounds of nature, but also on the military sounds nearby. The rest of the chapter focuses on his earnings and his cultivation of crops (including how he spends just under fifteen dollars on this).

The Village: The chapter focuses on Thoreau's reflections on the journeys he takes several times a week to Concord, where he gathers the latest gossip and meets with townsmen. On one of his journeys into Concord, Thoreau is detained and jailed for his refusal to pay a poll tax to the "state that buys and sells men, women, and children, like cattle at the door of its senate-house".[8]

The Ponds: In autumn, Thoreau discusses the countryside and writes down his observations about the geography of Walden Pond and its neighbors: Flint's Pond (or Sandy Pond), White Pond, and Goose Pond. Although Flint's is the largest, Thoreau's favorites are Walden and White ponds, which he describes as lovelier than diamonds.

Baker Farm: While on an afternoon ramble in the woods, Thoreau gets caught in a rainstorm and takes shelter in the dirty, dismal hut of John Field, a penniless but hard-working Irish farmhand, and his wife and children. Thoreau urges Field to live a simple but independent and fulfilling life in the woods, thereby freeing himself of employers and creditors. But the Irishman won't give up his aspirations of luxury and the quest for the American dream.

Higher Laws: Thoreau discusses whether hunting wild animals and eating meat is necessary. He concludes that the primitive, carnal sensuality of humans drives them to kill and eat animals, and that a person who transcends this propensity is superior to those who cannot. (Thoreau eats fish and occasionally salt pork and woodchuck.)[4] In addition to vegetarianism, he lauds chastity, work, and teetotalism. He also recognizes that Native Americans need to hunt and kill moose for survival in "The Maine Woods", and eats moose on a trip to Maine while he was living at Walden.[4] Here is a list of the laws that he mentions:

- One must love that of the wild just as much as one loves that of the good.

- What men already know instinctively is true humanity.

- The hunter is the greatest friend of the animal which is hunted.

- No human older than an adolescent would wantonly murder any creature which reveres its own life as much as the killer.

- If the day and the night make one joyful, one is successful.

- The highest form of self-restraint is when one can subsist not on other animals, but of plants and crops cultivated from the earth.

Brute Neighbors: is a simplified version of one of Thoreau's conversations with William Ellery Channing, who sometimes accompanied Thoreau on fishing trips when Channing had come up from Concord. The conversation is about a hermit (himself) and a poet (Channing) and how the poet is absorbed in the clouds while the hermit is occupied with the more practical task of getting fish for dinner and how in the end, the poet regrets his failure to catch fish. The chapter also mentions Thoreau's interaction with a mouse that he lives with, the scene in which an ant battles a smaller ant, and his frequent encounters with cats.

House-Warming: After picking November berries in the woods, Thoreau adds a chimney, and finally plasters the walls of his sturdy house to stave off the cold of the oncoming winter. He also lays in a good supply of firewood, and expresses affection for wood and fire.

Former Inhabitants; and Winter Visitors: Thoreau relates the stories of people who formerly lived in the vicinity of Walden Pond. Then he talks about a few of the visitors he receives during the winter: a farmer, a woodchopper, and his best friend, the poet Ellery Channing.

Winter Animals: Thoreau amuses himself by watching wildlife during the winter. He relates his observations of owls, hares, red squirrels, mice, and various birds as they hunt, sing, and eat the scraps and corn he put out for them. He also describes a fox hunt that passes by.

The Pond in Winter: Thoreau describes Walden Pond as it appears during the winter. He says he has sounded its depths and located an underground outlet. Then he recounts how 100 laborers came to cut great blocks of ice from the pond, the ice to be shipped to the Carolinas.

Spring: As spring arrives, Walden and the other ponds melt with powerful thundering and rumbling. Thoreau enjoys watching the thaw, and grows ecstatic as he witnesses the green rebirth of nature. He watches the geese winging their way north, and a hawk playing by itself in the sky. As nature is reborn, the narrator implies, so is he. He departs Walden on September 6, 1847.

Conclusion: This final chapter is more passionate and urgent than its predecessors. In it, he criticizes conformity: "If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music which he hears, however measured or far away", By doing so, men may find happiness and self-fulfillment.

I do not say that John or Jonathan will realize all this; but such is the character of that morrow which mere lapse of time can never make to dawn. The light which puts out our eyes is darkness to us. Only that day dawns to which we are awake. There is more day to dawn. The sun is but a morning star.[9]

Themes

Walden is a difficult book to read for three reasons: First, it was written in an older prose, which uses surgically precise language, extended, allegorical metaphors, long and complex paragraphs and sentences, and vivid, detailed, and insightful descriptions. Thoreau does not hesitate to use metaphors, allusions, understatement, hyperbole, personification, irony, satire, metonymy, synecdoche, and oxymorons, and he can shift from a scientific to a transcendental point of view in mid-sentence. Second, its logic is based on a different understanding of life, quite contrary to what most people would call common sense. Ironically, this logic is based on what most people say they believe. Thoreau, recognizing this, fills Walden with sarcasm, paradoxes, and double entendres. He likes to tease, challenge, and even fool his readers. And third, quite often any words would be inadequate at expressing many of Thoreau's non-verbal insights into truth. Thoreau must use non-literal language to express these notions, and the reader must reach out to understand.

Walden emphasizes the importance of solitude, contemplation, and closeness to nature in transcending the "desperate" existence that, he argues, is the lot of most people. The book is not a traditional autobiography, but combines autobiography with a social critique of contemporary Western culture's consumerist and materialist attitudes and its distance from and destruction of nature.[11] That the book is not simply a criticism of society, but also an attempt to engage creatively with the better aspects of contemporary culture, is suggested both by Thoreau's proximity to Concord society and by his admiration for classical literature. There are signs of ambiguity, or an attempt to see an alternative side of something common. Some of the major themes that are present within the text are:

- Self-reliance: Thoreau constantly refuses to be in "need" of the companionship of others. Though he realizes its significance and importance, he thinks it unnecessary to always be in search for it. Self-reliance, to him, is economic and social and is a principle that in terms of financial and interpersonal relations is more valuable than anything. To Thoreau, self-reliance can be both spiritual as well as economic. Connection to transcendentalism and to Emerson's essay.

- Simplicity: Simplicity seems to be Thoreau's model for life. Throughout the book, Thoreau constantly seeks to simplify his lifestyle: he patches his clothes rather than buy new ones, he minimizes his consumer activity, and relies on leisure time and on himself for everything.

- Progress: In a world where everyone and everything is eager to advance in terms of progress, Thoreau finds it stubborn and skeptical to think that any outward improvement of life can bring inner peace and contentment.

- The need for spiritual awakening: Spiritual awakening is the way to find and realize the truths of life which are often buried under the mounds of daily affairs. Thoreau holds the spiritual awakening to be a quintessential component of life. It is the source from which all of the other themes flow.

- Man as part of nature

- Nature and its reflection of human emotions

- The state as unjust and corrupt

- Meditation: Thoreau was an avid meditator and often spoke about the benefits of meditating.

Origins and publishing history

There has been much guessing as to why Thoreau went to the pond. E. B. White stated on this note, "Henry went forth to battle when he took to the woods, and Walden is the report of a man torn by two powerful and opposing drives—the desire to enjoy the world and the urge to set the world straight",[5] while Leo Marx noted that Thoreau's stay at Walden Pond was an experiment based on his teacher Emerson's "method of nature" and that it was a "report of an experiment in transcendental pastorialism".[5]

Likewise others have assumed Thoreau's intentions during his time at Walden Pond was "to conduct an experiment: Could he survive, possibly even thrive, by stripping away all superfluous luxuries, living a plain, simple life in radically reduced conditions?"[12] He thought of it as an experiment in "home economics". Although Thoreau went to Walden to escape what he considered, "over-civilization", and in search of the "raw" and "savage delight" of the wilderness, he also spent considerable amounts of his time reading and writing.

Thoreau spent nearly four times as long on the Walden manuscript as he actually spent at the cabin. Upon leaving Walden Pond and at Emerson's request, Thoreau returned to Emerson's house and spent the majority of his time paying debts. During those years Thoreau slowly edited and drafted what were originally 18 essays describing his "experiment" in basic living. After eight drafts over the course of ten years, Walden was published in 1854.[12]

After Walden's publication, Thoreau saw his time at Walden as nothing more than an experiment. He never took seriously "the idea that he could truly isolate himself from others".[13] Without resolution, Thoreau used "his retreat to the woods as a way of framing a reflection on both what ails men and women in their contemporary condition and what might provide relief".[14]

Reception

Walden enjoyed some success upon its release, but still took five years to sell 2,000 copies,[15] and then went out of print until Thoreau's death in 1862.[16] Despite its slow beginnings, later critics have praised it as an American classic that explores natural simplicity, harmony, and beauty. The American poet Robert Frost wrote of Thoreau, "In one book ... he surpasses everything we have had in America".[17]

It is often assumed that critics initially ignored Walden, and that those who reviewed the book were evenly split or slightly more negative than positive in their assessment of it. But researchers have shown that Walden actually was "more favorably and widely received by Thoreau's contemporaries than hitherto suspected."[18] Of the 66 initial reviews that have been found so far, 46 "were strongly favorable."[18] Some reviews were rather superficial, merely recommending the book or predicting its success with the public; others were more lengthy, detailed, and nuanced with both positive and negative comments. Positive comments included praise for Thoreau's independence, practicality, wisdom, "manly simplicity",[19] and fearlessness. Not surprisingly, less than three weeks after the book's publication, Thoreau's mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson proclaimed, "All American kind are delighted with Walden as far as they have dared to say."[20]

On the other hand, the terms "quaint" or "eccentric" appeared in over half of the book's initial reviews.[18] Other terms critical of Thoreau included selfish, strange, impractical, privileged (or "manor born"[21]), and misanthropic.[22] One review compared and contrasted Thoreau's form of living to communism, probably not in the sense of Marxism, but instead of communal living or religious communism. While valuing freedom from possessions, Thoreau was not communal in the sense of practicing sharing or of embracing community. So, communism "is better than our hermit's method of getting rid of encumbrance."[23]

In contrast to Thoreau's "manly simplicity", nearly twenty years after Thoreau's death Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson judged Thoreau's endorsement of living alone in natural simplicity, apart from modern society, to be a mark of effeminacy, calling it "womanish solicitude; for there is something unmanly, something almost dastardly" about the lifestyle.[24] Poet John Greenleaf Whittier criticized what he perceived as the message in Walden that man should lower himself to the level of a woodchuck and walk on four legs. He said: "Thoreau's Walden is a capital reading, but very wicked and heathenish ... After all, for me, I prefer walking on two legs".[25] Author Edward Abbey criticized Thoreau's ideas and experiences at Walden in detail throughout his response to Walden called "Down the River with Thoreau", written in 1980.[26]

Today, despite these criticisms, Walden stands as one of America's most celebrated works of literature. John Updike wrote of Walden, "A century and a half after its publication, Walden has become such a totem of the back-to-nature, preservationist, anti-business, civil-disobedience mindset, and Thoreau so vivid a protester, so perfect a crank and hermit saint, that the book risks being as revered and unread as the Bible."[27] The American psychologist B. F. Skinner wrote that he carried a copy of Walden with him in his youth,[28] and eventually wrote Walden Two in 1945, a fictional utopia about 1,000 members who live together in a Thoreau-inspired community.[29]

Kathryn Schulz has accused Thoreau of hypocrisy, misanthropy and being sanctimonious based on his writings in Walden,[30] although this criticism has been perceived as highly selective.[31][32]

Adaptations

Video games

The National Endowment for the Arts in 2012 bestowed Tracy Fullerton, game designer and professor at the University of Southern California's Game Innovation Lab with a $40,000 grant to create, based on the book, a first person, open world video game called Walden, a game,[33] in which players "inhabit an open, three-dimensional game world which will simulate the geography and environment of Walden Woods".[34] The game production was also supported by grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities and was part of the Sundance New Frontier Story Lab in 2014. The game was released to critical acclaim on July 4, 2017, celebrating both the day that Thoreau went down to the pond to begin his experiment and the 200th anniversary of Thoreau's birth. It was nominated for the Off-Broadway Award for Best Indie Game at the New York Game Awards 2018.[35]

Furthermore, Walden was adapted into an iOS app published by a third party developer. Walden: Life in the Woods is a quick play-through 2D game in which the player can, "explore the woods surrounding Walden Pond and play Thoreau inspired mini games."

Digitization and scholarship efforts

Digital Thoreau,[36] a collaboration among the State University of New York at Geneseo, the Thoreau Society, and the Walden Woods Project, has developed a fluid text edition of Walden[37] across the different versions of the work to help readers trace the evolution of Thoreau's classic work across seven stages of revision from 1846 to 1854. Within any chapter of Walden, readers can compare up to seven manuscript versions with each other, with the Princeton University Press edition,[38] and consult critical notes drawn from Thoreau scholars, including Ronald Clapper's dissertation The Development of Walden: A Genetic Text[39] (1967) and Walter Harding's Walden: An Annotated Edition[40] (1995). Ultimately, the project will provide a space for readers to discuss Thoreau in the margins of his texts.

Influence

Jean Craighead George's My Side of the Mountain trilogy draws heavily from themes expressed in Walden. Protagonist Sam Gribley is nicknamed "Thoreau" by an English teacher he befriends.

Shane Carruth's second film Upstream Color features Walden as a central item of its story, and draws heavily on the themes expressed by Thoreau.

The title of the gay men’s culture and news magazine Drum, which began publication in 1964, was inspired by a Walden quote that appeared in every edition: “If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears the beat of a different drummer.”[41]

The 1989 film Dead Poets Society heavily features an excerpt from Walden as a motif in the plot.

The Finnish symphonic metal band Nightwish makes several references to Walden on their eighth studio album Endless Forms Most Beautiful of 2015, including in the song titled "My Walden".

The investment research firm Morningstar, Inc. was named for the last sentence in Walden by founder and CEO Joe Mansueto, and the "O" in the company's logo is shaped like a rising sun.

In the 2015 video game Fallout 4, which takes place in Massachusetts, there exists a location called Walden Pond, where the player can listen to an automated tourist guide detail Thoreau's experience living in the wilderness. At the location there stands a small house which is said to be the same house Thoreau built and stayed in.

Phoebe Bridgers references the book in her song Smoke Signals.

In 2018, MC Lars and Mega Ran released a song called Walden where they discuss the book and its influence.

In the 1997 episode Weight Gain 4000 of South Park, Eric Cartman "writes" a prize-winning essay copied from Walden, replacing Thoreau's name with his own.

Notes

- Alfred, Randy (August 9, 2010). "Aug. 9, 1854: Thoreau Warns, 'The Railroad Rides on Us'". Wired News. Retrieved August 8, 2011.

- transcendentalism and social reform by Philip F. Gura], Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

- Grammardog Guide to Walden, by Henry David Thoreau, Grammardog LLC, ISBN 1-60857-084-3, p. 25

- Smith, Delivered at the Thoreau Society Annual Gathering, on July 14, 2007, Richard. "Thoreau's First Year at Walden in Fact & Fiction". Retrieved May 3, 2014.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Thoreau, Henry David. Walden Civil Disobedience and Other Writings. W.W. Norton & Company, 2008, p. 61.

- "The Maine Woods Henry David Thoreau Edited by Joseph J. Moldenhauer With a new introduction by Paul Theroux" (Press release). Princeton University. January 2004. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- Thoreau, Henry David. "Walden Civil Disobedience and Other Writings. W. W. Norton & Company, 2008, p. 96.

- "Walden Study Guide : Summary and Analysis of Chapters 1–3". GradeSaver. September 30, 2000. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- "Walden, and on the Duty of Civil Disobedience, by Henry David Thoreau". Gutenberg.org. January 26, 2013. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 18, 2006. Retrieved December 28, 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Johnson, Peter Anto (April 2018). "Perspectives of Civilization: New Beginnings After the End". Digital Literature Review. 5: 17–23.

- Levin, Jonathan (2003). Introduction. Walden and Civil Disobedience. Barnes and Noble Classics. ISBN 978-1-59308-208-6.

- Levin. p. 24

- Levin. p. 34

- "Henry David Thoreau (American writer): Works". Britannica.com. April 18, 2013. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- Dean, Bradley P.; Scharnhorst, Gary (1990). "The Contemporary Reception of Walden". Studies in the American Renaissance: 293–328.

- Frost, Robert. "Letter to Wade Van Dore", (June 24, 1922), in Twentieth Century Interpretations of Walden, ed. Richard Ruland. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, Inc. (1968), 8. LCCN 68-14480.

- Dean and Scharnhorst 293.

- Dean and Scharnhorst 302.

- Quoted in Dean and Scharnhorst 293, from Ralph L. Rusk (ed.), The Letters from Ralph Waldo Emerson (vol. 4), (New York: Columbia University Press, 1939) pp. 459–60.

- Dean and Scharnhorst 300.

- Dean and Scharnhorst 293–328.

- Dean and Scharnhorst 298.

- "Henry David Thoreau: His Character and Opinions". Cornhill Magazine. June 1880.

- Wagenknecht, Edward. John Greenleaf Whittier: A Portrait in Paradox. New York: Oxford University Press, 1967: 112.

- Abbey, Edward (1980). "Down the River with Thoreau". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - John Updike, "A Sage for all seasons", The Guardian, June 25, 2004

- Skinner, B. F. A Matter of Consequences. 1938

- Skinner, B. F. Walden 2. 1942

- Schulz, Kathryn (October 19, 2015). "Henry David Thoreau, Hypocrite". The New Yorker. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- Malesic, Jonathan (October 19, 2015). "Henry David Thoreau's Radical Optimism". New Republic. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- Hohn, Donovan (October 21, 2015). "Everybody Hates Henry". New Republic. Archived from the original on October 26, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- http://www.waldengame.com

- Flood, Alison (April 26, 2012). "Walden Woods video game will recreate the world of Thoreau". The Guardian. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- Whitney, Kayla (January 25, 2018). "Complete list of winners of the New York Game Awards 2018". AXS. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- "digitalthoreau.org". digitalthoreau.org. July 18, 2013. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- "Walden: a Fluid Text Edition".

- "Thoreau, H.D.; Shanley, J.L., ed.: The Writings of Henry David Thoreau: Walden. (Hardcover)". Press.princeton.edu. April 17, 2014. Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- The development of Walden: a genetic text. (Book, 1968). [WorldCat.org]. February 22, 1999. OCLC 1166552.

- Walden : an annotated edition (Book, 1995). [WorldCat.org]. May 8, 2012. OCLC 31709850.

- Streitmatter, Rodger (1995). Unspeakable: The Rise of the Gay and Lesbian Press in America. Boston, Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-19873-2, p. 60

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Walden. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Walden |

- Walden at Standard Ebooks

- Walden at Project Gutenberg

- Walden – Digitized copy of the first edition from the Internet Archive.

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- Walden: An Annotated Edition (hyperlinked TOC, footnotes and scholarly commentary). R. Lenat (ed.). Thoreau Society and Iowa State University project.