Right to education

The right to education has been recognized as a human right in a number of international conventions, including the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights which recognizes a right to free, compulsory primary education for all, an obligation to develop secondary education accessible to all, on particular by the progressive introduction of free secondary education, as well as an obligation to develop equitable access to higher education, ideally by the progressive introduction of free higher education. Today, almost 75 million children across the world are prevented from going to school each day.[1] As of 2015, 164 states were parties to the Covenant.[2]

| Education |

|---|

| Disciplines |

| Curricular domains |

|

| Methods |

The right to education also includes a responsibility to provide basic education for individuals who have not completed primary education from the school and college levels. In addition to these access to education provisions, the right to education encompasses the obligations of the students to avoid discrimination at all levels of the educational system, to set minimum standards of education and to improve the quality of education.

International legal basis

The right to education is reflected in international law in Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and Articles 13 and 14 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.[3][4][5] Article 26 states:

"Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory. Technical and professional education shall be made generally available and higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit. Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. It shall promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations, racial or religious groups, and shall further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace. Parents have a prior right to choose the kind of education that shall be given to their children."[6]

The right to education has been reaffirmed in the 1960 UNESCO Convention against Discrimination in Education, the 1981 Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women,[7] the 2006 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities,[8] and the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights.[9]

In Europe, Article 2 of the first Protocol of 20 March 1952 to the European Convention on Human Rights states that the right to education is recognized as a human right and is understood to establish an entitlement to education. According to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, the right to education includes the right to free, compulsory primary education for all, an obligation to develop secondary education accessible to all in particular by the progressive introduction of free secondary education, as well as an obligation to develop equitable access to higher education in particular by the progressive introduction of free higher education. The right to education also includes a responsibility to provide basic education for individuals who have not completed primary education. In addition to these access to education provisions, the right to education encompasses also the obligation to eliminate discrimination at all levels of the educational system, to set minimum standards, and to improve quality. The European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg has applied this norm for example in the Belgian linguistic case.[7] Article 10 of the European Social Charter guarantees the right to vocational education.[10]

Definition

Education consists of formal institutional instructions. Generally, international instruments use the term in this sense and the right to education, as protected by international human rights instruments, refers primarily to education in a narrow sense. The 1960 UNESCO Convention against Discrimination in Education defines education in Article 1(2) as: "all types and levels of education, (including such) access to education, the standard and quality of education, and the conditions under which it is given."[11]

In a wider sense education may describe "all activities by which a human group transmits to its descendants a body of knowledge and skills and a moral code which enable the group to subsist".[11] In this sense education refers to the transmission to a subsequent generation of those skills needed to perform tasks of daily living, and further passing on the social, cultural, spiritual and philosophical values of the particular community. The wider meaning of education has been recognised in Article 1(a) of UNESCO's 1974 Recommendation concerning Education for International Understanding, Co-operation and Peace and Education relating to Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms.[12]

"the entire process of social life by means of which individuals and social groups learn to develop consciously within, and for the benefit of, the national and international communities, the whole of their personal capabilities, attitudes, aptitudes and knowledge."[11]

The European Court of Human Rights has defined education in a narrow sense as "teaching or instructions... in particular to the transmission of knowledge and to intellectual development" and in a wider sense as "the whole process whereby, in any society, adults endeavour to transmit their beliefs, culture and other values to the young."[11]

The Abidjan principles were passed in early 2019 and provide comprehensive guiding principles on the intersection between private education and the right to education

Assessment of fulfilment

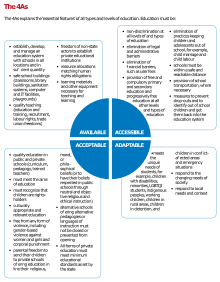

The fulfilment of the right to education can be assessed using the 4 As framework, which asserts that for education to be a meaningful right it must be available, accessible, acceptable and adaptable. The 4 As framework was developed by the former UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Education, Katarina Tomasevski, but is not necessarily the standard used in every international human rights instrument and hence not a generic guide to how the right to education is treated under national law.[13]

The 4 As framework proposes that governments, as the prime duty-bearers, have to respect, protect and fulfil the right to education by making education available, accessible, acceptable and adaptable. The framework also places duties on other stakeholders in the education process: the child, which as the privileged subject of the right to education has the duty to comply with compulsory education requirements, the parents as the ‘first educators’, and professional educators, namely teachers.[13]

The 4 As have been further elaborated as follows:[14]

- Availability – funded by governments, education is universal, free and compulsory. There should be proper infrastructure and facilities in place with adequate books and materials for students. Buildings should meet both safety and sanitation standards, such as having clean drinking water. Active recruitment, proper training and appropriate retention methods should ensure that enough qualified staff is available at each school.[15]

- Accessibility – all children should have equal access to school services, regardless of gender, race, religion, ethnicity or socio-economic status. Efforts should be made to ensure the inclusion of marginalized groups including children of refugees, the homeless or those with disabilities; in short there should be universal access to education i.e. access to all. Children who fall into[16] poverty should be granted the access of education because it enhances the growth of their mental and social state. There should be no forms of segregation or denial of access to any students. This includes ensuring that proper laws are in place against any child labour or exploitation to prevent children from obtaining primary or secondary education. Schools must be within a reasonable distance for children within the community, otherwise transportation should be provided to students, particularly those that might live in rural areas, to ensure ways to school are safe and convenient. Education should be affordable to all, with textbooks, supplies and uniforms provided to students at no additional costs.[17]

- Acceptability – the quality of education provided should be free of discrimination, relevant and culturally appropriate for all students. Students should not be expected to conform to any specific religious or ideological views. Methods of teaching should be objective and unbiased and material available should reflect a wide array of ideas and beliefs. Health and safety should be emphasized within schools including the elimination of any forms of corporal punishment. Professionalism of staff and teachers should be maintained.[18]

- Adaptability – educational programs should be flexible and able to adjust according to societal changes and the needs of the community. Observance of religious or cultural holidays should be respected by schools in order to accommodate students, along with providing adequate care to those students with disabilities.[19]

A number of international NGOs and charities work to realise the right to education using a rights-based approach to development.[1]

Historical development

In Europe, before the Enlightenment of the eighteenth and nineteenth century, education was the responsibility of parents and the church. With the French and American Revolution, education was established also as a public function. It was thought that the state, by assuming a more active role in the sphere of education, could help to make education available and accessible to all. Education had thus far been primarily available to the upper social classes and public education was perceived as a means of realising the egalitarian ideals underlining both revolutions.[20]

However, neither the American Declaration of Independence (1776) nor the French Declaration of the Rights of Man (1789) protected the right to education, as the liberal concepts of human rights in the nineteenth century envisaged that parents retained the primary duty for providing education to their children. It was the states obligation to ensure that parents complied with this duty, and many states enacted legislation making school attendance compulsory. Furthermore, child labour laws were enacted to limit the number of hours per day children could be employed, to ensure children would attend school. States also became involved in the legal regulation of curricula and established minimum educational standards.[21]

In On Liberty John Stuart Mill wrote that an "education established and controlled by the State should only exist, if it exists at all, as one among many competing experiments, carried on for the purpose of example and stimulus to keep the others up to a certain standard of excellence." Liberal thinkers of the nineteenth century pointed to the dangers to too much state involvement in the sphere of education, but relied on state intervention to reduce the dominance of the church, and to protect the right to education of children against their own parents. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, educational rights were included in domestic bills of rights.[21] The 1849 Paulskirchenverfassung, the constitution of the German Empire, strongly influenced subsequent European constitutions and devoted Article 152 to 158 of its bill of rights to education. The constitution recognised education as a function of the state, independent of the church. Remarkable at the time, the constitution proclaimed the right to free education for the poor, but the constitution did not explicitly require the state to set up educational institutions. Instead the constitution protected the rights of citizens to found and operate schools and to provide home education. The constitution also provided for freedom of science and teaching, and it guaranteed the right of everybody to choose a vocation and train for it.[22]

The nineteenth century also saw the development of socialist theory, which held that the primary task of the state was to ensure the economic and social well-being of the community through government intervention and regulation. Socialist theory recognised that individuals had claims to basic welfare services against the state and education was viewed as one of these welfare entitlements. This was in contrast to liberal theory at the time, which regarded non-state actors as the prime providers of education. Socialist ideals were enshrined in the 1936 Soviet Constitution, which was the first constitution to recognise the right to education with a corresponding obligation of the state to provide such education. The constitution guaranteed free and compulsory education at all levels, a system of state scholarships and vocational training in state enterprises. Subsequently, the right to education featured strongly in the constitutions of socialist states.[22] As a political goal, right to education was declared in F. D. Roosevelt's 1944 speech on the Second Bill of Rights.

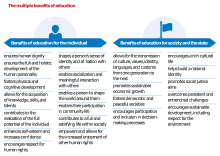

The role of education for individuals, the society and the state

Education in all its forms (informal, non-formal, and formal) is crucial to ensure human dignity of all individuals. The aims of education, as set out in the International human rights law (IHRL), are therefore all directed to the realization of the individual’s rights and dignity.[23] These include, among others, ensuring human dignity and the full and holistic development of the human personality; fostering physical and cognitive development; allowing for the acquisition of knowledge, skills, and talents; contributing to the realization of the full potential of the individual; enhancing self-esteem and increasing confidence; encouraging respect for human rights; shaping a person’s sense of identity and affiliation with others; enabling socialization and meaningful interaction with others; enabling a person to shape the world around them enables their participation in community life; contributing to a full and satisfying life within society; and empowering and allowing for the increased enjoyment of other human rights.[24]

Education is also transformative for the state and society. As one of the most important mechanisms by which social groups, in particular indigenous peoples and minorities are maintained from generation to generation, passing on language, culture, identity, values, and customs, education is also one of the key ways states can ensure their economic, social, political, and cultural interests.[24]

The main role of education within a society and the state is to:[24]

- Allow for the transmission of culture, values, identity, languages, and customs from one generation to the next;

- Promote sustainable economic growth;

- Foster democratic and peaceful societies;

- Encourage participation and inclusion in decision-making processes;

- Encourage a rich cultural life;

- Help build a national identity;

- Promote social justice aims;

- Overcome persistent and entrenched challenges;

- Encourage sustainable development, including respect for the environment.[24]

Implementation

International law does not protect the right to pre-primary education and international documents generally omit references to education at this level.[25] The Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that everyone has the right to education, hence the right applies to all individuals, although children are considered as the main beneficiaries.[26]

The rights to education are separated into three levels:

- Primary (Elemental or Fundamental) Education. This shall be compulsory and free for any child regardless of their nationality, gender, place of birth, or any other discrimination. Upon ratifying the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights States must provide free primary education within two years.

- Secondary (or Elementary, Technical and Professional in the UDHR) Education must be generally available and accessible.

- At the University Level, Education should be provided according to capacity. That is, anyone who meets the necessary education standards should be able to go to university.

Both secondary and higher education shall be made accessible "by every appropriate means, and in particular by the progressive introduction of free education".[27]

Compulsory education

The realization of the right to education on a national level may be achieved through compulsory education, or more specifically free compulsory primary education, as stated in both the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.[3][28]

Right to education for children

The rights of all children from early childhood stem from the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The declaration proclaimed in article 1: ‘All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights’. The declaration states that human rights begin at birth and that childhood is a period demanding special care and assistance [art. 25 (2)]. The 1959 Declaration of the Rights of the Child affirmed that: ‘mankind owes to the child the best it has to give’, including education. This was amplified by the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of 1966 which states that: ‘education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and the sense of its dignity, and shall strengthen the respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. [art. 13 (1)][29]

The World Declaration on Education for All (EFA) adopted in 1990 in Jomtien, Thailand, states in article 5 that: ‘Learning begins at birth [...] This calls for early childhood care and initial education.’ A decade later, the Dakar Framework for Action on EFA established six goals, the first of which was: ‘expanding and improving early childhood care and education, especially for the most vulnerable and disadvantaged children.’ Protection of children of all ages from exploitation and actions that would jeopardize their health, education and well-being has also been emphasized by the International Labour Organization in Conventions No. 138 on the Minimum Age of Employment (1973) and No. 182 on the Prohibition and Immediate Action for the Elimination of the Worst Forms of Child Labour (1999). The United Nations contributed to such endeavours by the Declaration of the Rights of the Child unanimously adopted by the General Assembly in 1959.[29]

The impact of privatization on the right to education

The privatization of education can have a positive impact for some social groups, in the form of increased availability of learning opportunities, greater parental choice and a wider range of curricula. However, it can also have negative effects resulting from insufficient or inadequate monitoring and regulation by the public authorities (schools without licences, hiring of untrained teachers and absence of quality assurance), with potential risks for social cohesion and solidarity. Of particular concern: "Marginalised groups fail to enjoy the bulk of positive impacts and also bear the disproportionate burden of the negative impacts of privatisation."[30] Furthermore, uncontrolled fees demanded by private providers could undermine universal access to education. More generally, this could have a negative impact on the enjoyment of the right to a good quality education and on the realization of equal educational opportunities.[31]

Supplemental private tutoring, or ‘shadow education’, which represents one specific dimension of the privatization of education, is also growing worldwide.[32] Often a symptom of badly functioning school systems,[33] private tutoring, much like other manifestations of private education, can have both positive and negative effects for learners and their teachers. On one hand, teaching can be tailored to the needs of slower learners and teachers can supplement their school salaries. On the other hand, fees for private tutoring may represent a sizeable share of household income, particularly among the poor, and can therefore create inequalities in learning opportunities. And the fact that some teachers may put more effort into private tutoring and neglect their regular duties can adversely affect the quality of teaching and learning at school.[34] The growth of shadow education, the financial resources mobilized by individuals and families, and the concerns regarding possible teacher misconduct and corruption are leading some ministries of education to attempt to regulate the phenomenon.[31][34]

See also

- Academic freedom

- Economic, social and cultural rights

- Education 2030 Agenda

- Educational equity

- Female education

- Free education

- Freedom of education

- History of childhood care and education

- Literacy

- Mobile learning for refugees

- Open educational resources

- Scholarship

- Universal access to education

- World Education Forum

Lawsuits

- Mohini Jain v. State of Karnataka (1992 AIR 1858) or (AIR 1992 SC 2100), in India.

References

- "What is HRBAP? | Human Rights-based Approach to Programming | UNICEF". UNICEF. Retrieved 2016-09-28.

- "UN Treaty Collection: International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights". UN. 3 January 1976. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- Article 26, Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- Article 13, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Archived 2012-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Article 14, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Archived 2012-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- "Article 26". claiminghumanrights.org. Retrieved 2016-10-05.

- A Human Rights-Based Approach to Education for All (PDF). UNESCO/UNICEF. 2007. p. 7.

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Article 24

- "African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights / Legal Instruments". achpr.org. Retrieved 2016-01-12.

- European Social Charter, Article 10

- Beiter, Klaus Dieter (2005). The Protection of the Right to Education by International Law. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. p. 19. ISBN 90-04-14704-7.

- Beiter, Klaus Dieter (2005). The Protection of the Right to Education by International Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 226–227. ISBN 9789004147041.

- "Right to education – What is it? Education and the 4 As". Right to Education project. Retrieved 2009-02-21.

- "Right to education – What is it? Primer on the right to education". Right to Education project. Archived from the original on 2009-03-02. Retrieved 2009-02-21.

- "Right to education – What is it? Availability". Right to Education project. Retrieved 2010-09-11.

- "Understanding education as a right". Right to Education Project. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- "Right to education – What is it? Accessibility". Right to Education project. Retrieved 2010-09-11.

- "Right to education – What is it? Acceptability". Right to Education project. Retrieved 2010-09-11.

- "Right to education – What is it? Adaptability". Right to Education project. Retrieved 2010-09-11.

- Beiter, Klaus Dieter (2005). The Protection of the Right to Education by International Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 21–22. ISBN 9789004147041.

- Beiter, Klaus Dieter (2005). The Protection of the Right to Education by International Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 22. ISBN 9789004147041.

- Beiter, Klaus Dieter (2005). The Protection of the Right to Education by International Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 23. ISBN 9789004147041.

- "General comment No. 1 (2001), Article 29 (1), The aims of education".

- "Right to education handbook". ISBN 978-92-3-100305-9.

- Beiter, Klaus Dieter (2005). The Protection of the Right to Education by International Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 19–20. ISBN 9789004147041.

- Beiter, Klaus Dieter (2005). The Protection of the Right to Education by International Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 20. ISBN 9789004147041.

- Article 13 (2) (a) to (c), International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

- Article 14, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights

- Marope, P.T.M.; Kaga, Y. (2015). Investing against Evidence: The Global State of Early Childhood Care and Education (PDF). Paris, UNESCO. pp. 38–39. ISBN 978-92-3-100113-0.

- Right to Education Project (2014). Privatisation of Education: Global Trends of Human Rights Impacts (PDF).

- Rethinking Education: Towards a global common good? (PDF). UNESCO. 2015. pp. 74–75. ISBN 978-92-3-100088-1.

- Confronting the shadow education system. What government policies for what private tutoring?. Paris, UNESCO-WEEPIE. 2009.

- UNESCO (2014). "Teaching and Learning: Achieving quality for all". EFA Global Monitoring Report 2013-2014. Paris, UNESCO.

- Bray, M.; Kuo, O. (2014). "Regulating Private Tutoring for Public Good. Policy options for supplementary education in Asia". CERC Monograph Series in Comparative and International Education and Development. Hong Kong, Comparative Education Research Center and UNESCO Bangkok Office. No. 10.

Sources

External links

- Right for Education in Africa

- Right to Education UNESCO

- UN Special Rapporteur on the right to education

- Refugee Education in an International Perspective, dossier by Education Worldwide, a portal of the German Education

- The Human Right to Education: Definition, Research and Annotated Bibliography Emory International Law Review, Vol. 34, No. 3, 2020.