Education in Haiti

The Haitian Educational System yields the lowest total rate in the education realm of the Western Hemisphere.[3] Haiti's literacy rate of about 61% (64.3% for males and 57.3% for females) is below the 90% average literacy rate for Latin American and Caribbean countries.[1] The country faces shortages in educational supplies and qualified teachers. The rural population is less educated than the urban.[3] The 2010 Haiti earthquake exacerbated the already constrained parameters on Haiti's educational system by destroying infrastructure and displacing 50–90% of the students, depending on locale.

| |

| Ministry of National Education | |

|---|---|

| Minister of National Education & Professional Training | Pierre Josué Agénor CADET |

| General details | |

| Primary languages | French, Creole |

| Literacy (2015) | |

| Total | 60.7% (est. 2015)[1] |

| Male | 64.3% |

| Female | 57.3% |

| Primary | 88%[2] |

| [1] | |

International private schools (run by Canada, France, or the United States) and church-run schools educate 90% of students.[3] Haiti has 15,200 primary schools, of which 90% are non-public and managed by communities, religious organizations or NGOs.[4] The enrollment rate for primary school is 88%.[2] Secondary schools enroll 20% of eligible-age children. Higher education is provided by universities and other public and private institutions.

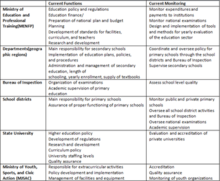

The educational sector is under the responsibility of the Ministre de l'Éducation Nationale et de la Formation Professionnelle (MENFP).[5] The Ministry provides very little funds to support public education. As a result, the private sector has become a substitute for governmental public investment in education as opposed to an addition.[6] The Ministry is limited in its ability to improve the quality of education in Haiti.[7]

Despite the deficiencies of the Haitian education sector, some Haitian leaders have attempted to make improving education a national goal. The country has attempted three major reform efforts, with a new one in progress as a response to the earthquake.[7][8]

History

Pre-independence

"African slaves were worked so hard by French plantation owners that half died within a few years; it was cheaper to import new slaves than to improve working conditions enough to increase survival. This attitude allowed no time or resources for the education of the enslaved.[9] Children of slaveholders were tutored in the early grades at home and then sent to France for further study. There were few schools in Saint Domingue. At the time of independence, years of war had demolished most infrastructure including any educational facilities.[9]

Independence through the 1800s

At the beginning of independence, King Christophe in the north of Haiti looked to Englishman William Wilberforce to build up the new nation's educational system.[9] King Christophe, though illiterate, understood the necessity of education. He was keen to show that formerly enslaved educated persons could hold their own with the educated of the world. Wilburforce encouraged Prince Saunders of Boston as well as four others to join their efforts at developing a Lancastrian model of education.[9] This is a Monitorial System where the teacher teaches the more advanced students who then in turn teach the less advanced. It is designed to educate a large number of students without benefit of a large number of professional teachers.

In the south of Haiti, President Alexandre Pétion turned to the French to guide his development of the educational system. He was personally familiar with it since he had studied ballistics in France.[9] His approach to the issue of inadequate numbers of teachers for the primary grades was to focus on secondary education in the Napoleonic approach to education.[10]

The first Constitution, promulgated in 1805 by King Christophe,[11] stated that "... education shall be free. Primary education shall be compulsory... State education shall be free at every level."[6] It guaranteed the right for everyone to teach –an "open-door policy" to private initiatives[12] which meant that every person would have the right to form private establishments for the education and instruction of youth.[8][13] The practice of providing accessible public education for all was established later when the Constitution was revised in 1807.[8]

In 1987, the declaration that education was a right for every citizen was added to the Constitution.[14] (These educational goals expressed in the Constitution have not been achieved. In the beginning, the government's primary focus was on building schools to serve the children of the political elite.[6] These schools were predominantly found in urban areas, and patterned after the French and British school models.[6] At the end of the 19th century, there were 350 public schools in the country. It rose to approximately 730 by the eve of the American Occupation of Haiti in 1917.[6])

The American Occupation of 1915–1934

At the beginning of the United States occupation of Haiti there was an effort by the U.S. military to improve the education but not to the degree to which they had in the previous countries that they had occupied such as Cuba or the Puerto Rico.[15] Their initial assessment of the Haitian educational system was similar to many that had been made before.[16] The solution of the military, as first understood – of broadening the type of education and opening it up to more of the population, was considered a positive change by many Haitians as well as a number of American editorial writers who were keeping an eye on Haiti.[17] The most basic issue was that the current educational system did not successfully educate the average Haitian who spoke only Haitian Creole. The Haitian education system was built on the idea of the superiority of the French language over any other language, and the profound inferiority of Haitian culture to that of the French culture. This concept of superiority were born in the minds of the elite during the years of slavery and were re-enforced when the French Catholic Church was allowed to return and begin establishing schools as a result of the Concordat of 1860. The classical education, more commonly called an "academic" education was meant to prepare the elite for further education in France. There was heavy emphasis on the literature of France and rhetoric and very little science or practical education such as engineering and the learning tended to be rote. The language of instruction was French which was further re-enforced at home, among friends and in their reading materials down to food labels in their pantries. Non-elite students did not have the benefit of speaking French at home. In the schools that served the non-elite, French was still the language of instruction but there was a good chance the teacher was not fluent and the teaching became even more rote. Further down the social ladder, the quality of the teacher's either Creole or French was even less certain.[18] To ensure universal education for all, it was clear that profound, deep, systemic changes would need to begin.[19]

The Occupation's solution, however, was different than prior attempts at repair in that there was to be a new and extreme emphasis on agricultural education over the traditional academic education that the elites received.[19] The decision process surrounding this move to agricultural education and its implementation caused a great deal of concern and controversy in Haiti as well as in the U.S. – particularly among black American leaders. To them it smacked of attempts in the southern United States to limit black citizens to simple agricultural training to keep them from moving up the social economic ladder and to keep them from moving into a profession or positions of leadership.[20] (Note that there was an ongoing debate in the United States among leaders of black people at the time about the best educational path for black Americans – see the discussions between Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Dubois [ whose father had been born in Haiti.][21] – however no black leader advocated for solely agricultural training.) US. black leaders discovered that the U.S. decision makers in Haiti were all white military men – the majority of whom were southerners raised with Jim Crow laws. Concerns were raised about systemic racism such that one such leader Rayford W. Logan – an American French speaking advocate of Pan-Africanism – went on a fact finding mission, traveling much of the country and examining documents published by the Occupational forces. While there was no systematic record- keeping for all the Occupation years or for all the other efforts in the occupied countries, he was able to see clear patterns of denial of funds and minimization of Haitian culture. He concluded that the occupation's educational efforts were failing due to issues related to racism – some subtle and some blatant.[17]

In the initial treaty with Haiti no mention was explicitly made of educational improvements or policy as had been done in the Philippines, Cuba and Puerto Rico.[22] Rayford considered this "an almost inexplicable omission".[23]

The Occupation budget for education in Haiti in 1920 paled in comparison to previous amounts allocated in other occupied countries. (Note that all monies for education came out of the Haitian treasury – there were no monies forthcoming from the United States.)[20][24]

- Haiti had $340,000.[25]

- Cuba had 20 times the budget ($7,000,000) for the same number of people.[25]

- Puerto Rico had 11 times the budget ($4,000,000) with half the people of Haiti.[25]

- Dominican Republic had 5 times the budget ($1,500,000) with a third of the people.[25]

While the U.S. was in the Dominican Republic, the salary of a teacher there had increased from $5 to $10 a month to $55 a month. Dominican rural schools had increased in number from 84 before the occupation to 489 in 1921. Logan attributed this disparity to racism, even though citizens of both countries were descended from African slaves.[17] The Dominican Republic citizens described themselves as white people or mulatto while Haitians described themselves as black or mulatto.[17]

In Haiti, the Occupation had essentially developed two school systems – one run by the U.S. – the agricultural sector called the Service Technique (or Technical Service) and the one run by the Haitian government – the academic from the elite lycee schools to the primary school in the mountain villages.

The implementation of the Service Techniques was highly problematic. The classes were taught by American teachers – few of whom spoke French let alone Haitian Creole. This required most classes to use translators which slowed down the teaching process considerably and added another cost.

Logan found that the salary differentials were such that Haitian primary school teachers were paid $72 a year while the American inspector of schools in that local area was paid between $1800 and $2400 a year. Academic schools were clearly deprived of funds while agricultural schools were generously funded. The Americans paid little attention to rural schools – home of the vast majority of Haitians.

After 13 years of Occupation there were only a third of the rural schools – 306 – as opposed to the 1074 required by the Haiti law of 1912.[26] There was also a dearth of government owned school buildings – Haiti had much more of a deficit in numbers of school buildings than other countries the U.S. had occupied. In the Philippines, the Occupation had built 1000 schools; in Cuba, 2600 schools with attendance jumping from 21,000 to 215,000.[27]

Given the concern about European influence in the Caribbean prior to World War I it is not surprising that Occupation forces wanted to diminish the influence of the Germans and French in Haitian life. Germans controlled important parts of the economy but it was the French who controlled the culture. It was much easier to replace the Germans with American businessmen but there was not an easy replacement for the French way of life. When the Haitian government asked that French Trappists (one of Catholicism's holy orders) be allowed to provide schooling, they were denied – even though this would have been a less expensive method of education. There was also a deep concern surrounding the separation of church and state among the Occupation leaders because it did not fit the model of American democracy. In the Americans' view the Catholic Church was intertwined with French influence and its reach into Haitian society needed to be reduced even though this would negatively affect academic education. At one point, two French professors were denied the ability to teach and the French Ambassador to the United States made an official complaint.[28] It was the hope of the Occupation to reduce cultural reliance on the French but the American military badly underestimated the intellectual, language and emotional ties to France among the elite.

There were some elite who at the beginning of the Occupation offered support for the Occupation's educational efforts but once it became it clear that there would not only be no support for the academic schools, that many of them would actually be closed – the elite became increasingly anti-American.[19]

While many in Haiti had a plethora of reasons to be frustrated with the Occupation it was actually students who instigated the final demonstrations against the Americans that finally forced them out. They had been promised scholarships to the Service Technique but did not receive them. It was the straw that broke the camel's back and began the revolt that ended the Occupation in 1934.[17][19][29][30]

Post Occupation (1931–1946)

Rural Education

Although the American Occupation officially ended in 1934 (with some aspects, such as finance and customs, actually continuing until 1947), the U.S. personnel running the Technical Service of Agriculture and Vocational Education (Service Technique de l'Agriculture et de l'Enseignement Professionnel) left in October 1931. Important changes in rural education began to be effected following their departure and the naming of Maurice Dartigue as Director of Rural Education (from 1931 to 1941). Significant innovations in urban education were made later when Dartigue was appointed Minister of Public Instruction, Agriculture and Labor, serving from 1941 to late 1945.

Initially, the Haitian Government was faced with a dilemma: where to house this service that the Occupation had created. The antiquated Department of Public Instruction was deemed unsuitable, as it had not been reorganized at any time in the past decade. As a result, the Technical Service was split in two, forming the National Service of Agricultural Production and Rural Education (Service National de la Production Agricole et de l'Enseignemnt Rural), under the Department of Agriculture, and the National Service of Vocational Education (Service National de l'Enseignement Professionnel), placed under the Department of Labor.

Since the Haitian educational system had been based wholly on a French curriculum, reflecting a classical approach, with courses in French, using French texts, the country now had the opportunity of a brand-new start that would make the education Haitian, modern, professional, and democratic.

The Haitianization of the system meant that Haitians would take the place of American teachers and administrators formerly in charge of the rural and vocational schools and that students would be presented with an approach to education that was relevant to their needs and to their milieu, a truly revolutionary concept for Haiti. This was augmented with books written specifically for Haitian children by rural-education specialists, including the ground-breaking Géographie locale (Local Geography) by Maurice Dartigue and André Liautaud, and in that same year (1931) Dartigue's civics textbook, Les Problèmes de la Communauté (The Problems of the Community), to help form good citizens.

This was also a chance to introduce a modern curriculum, one that combined a practical foundation in agriculture and manual trades with "book learning," i.e., the three Rs, elements of Haitian history and geography, social sciences, hygiene, and physical education – subjects that were of relevance to the children and their environment. It was also an opportunity to establish new teaching methods and for teachers to undergo proper training and, in many cases, retraining. Prior to 1931, the prevalent opinion had been that any individual with a certain amount of culture was capable of working in the various fields of education. This ignored the fact that education is both an art and a science that can only be organized and directed by competent specialists. The proper formation of teachers would also lead to the professionalization of education and to providing status and dignity for the profession.

The aim of the new education was to reach everyone. No longer would the system cater only to the 10% that had a mastery of French, while the other 90% — principally the country's rural citizens – remained largely illiterate. Education would finally be democratic and might lead to a democratic society. Children of all classes of society, all on an equal footing, would have the same opportunity for learning and for advancement in a land with a strict caste system that the peasantry could presently never escape.

Maurice Dartigue was a graduate of the Central School of Agriculture (which the Americans had established in 1924); had spent five years working for the Technical Service; and had earned a master's degree in rural education from Columbia University's Teachers College in New York. The reforms he undertook to revolutionize Haiti's rural educational system included many firsts.

The initial step was to conduct a comprehensive survey throughout the country, the statistical data from which was analyzed and used to evaluate the system's present and future needs and budgets. The survey revealed that conditions quoted in official reports and statements made by Haitian educators and intellectuals from 1884 to 1914 were still the same in 1931. As had been shown in 1892 (when the then-Minister of Public Instruction had indicated that most of the rural schools listed were in fact non-existent), any number of schools were still only on paper while quite a number consisted only of a rudimentary tonnelle (a shelter) with three or four benches. Very few, if any, had ever received supplies from the Department of Public Instruction. The exact location of many schools was unknown to the central office in Port-au-Prince and even to the district inspectors. In a number of cases, teachers stayed away from work for three, four or even six months a year. Those instructors who were found in their schools or could be reached during the survey were given a simple elementary test. Most of them were judged practically illiterate and unable to do basic arithmetic: they were absolutely incompetent.

The results of the survey demonstrated that it was not the fault of the peasants if they did not benefit from the rural schools allegedly established since 1860. The peasant was untutored not only in what we understand to be basic education (the three Rs) but also in the ways of the earth as to irrigation, fertilization, seed selection, crop rotation, terracing, reforestation, soil erosion, conservation, standardization for marketing, and the like, because up to this time no educational system had tried to give him the mental and technical equipment necessary to cope adequately with his problems. Meeting these problems head-on and solving them intelligently required a certain kind of instruction, a specific type of schooling, whereby economic proficiency was viewed as more important than literacy. The emphasis on economic competence needed to aim at creating earning power for the peasant. Schooling was also meant to develop in the peasantry reliability, responsibility, and leadership. In addition to imparting technical skills, it was necessary for the peasant's education to expose him to and provide training in the cultural, civic, and social aspects of his immediate world and the larger one of the Haitian nation. It was important to instill a unifying culture in the peasantry, to create a sense of the nation they belonged to, to have them embrace the values and qualities that could, with the middle and upper classes, join them into one society.

Rural education essentially meant primary schooling and was to cover a period of six years. Not only did it constitute the foundation of the educational system, but for the majority of rural students, it was all the education they were going to get because it was unlikely they would continue with further studies. It was therefore imperative that the pupils be given a minimum of knowledge.

Dartigue advocated a scientific approach to education and the application of the principles of pedagogy. For the first time, Haiti now had a rural educational system based on a philosophy of education and not on a blind imitation of foreign (i.e., French) programs. The education of girls was also deemed of great importance, for if there was to be improvement in peasant life, girls had to be schooled because progress, particularly social progress, is closely connected with the education of women. The number of schools for girls was increased, as were the number of mixed schools (girls and boys together), and more women were encouraged to enter the teaching profession.

Programs were undertaken to involve parents and the rest of the community in the idea of rural education as a way for adults to understand its purpose and value, not only for the children but for themselves as well. A vital bond needed to be established between the school and the community by centering as much as possible the life of the community around the rural schools so that they might exert an influence toward social and economic improvement of the community. This outreach was a new concept for Haiti. Recreational programs for children and parents were begun. Parent associations were formed and regular meetings held to discuss the problems of the school and the community. County agricultural agents explained newly enacted laws and regulations regarding agriculture and advised on the planting of crops, methods of cultivation, and marketing. They demonstrated good agricultural practices, and many seedlings and thousands of seeds were distributed free of charge. The peasants were also encouraged to bring their tools to be repaired in the school shop, and agricultural implements were sold at cost to the peasants of certain regions, while modern silos were built in different areas to conserve grain and stabilize prices throughout the year. Gradually, teachers and pupils, with the occasional aid of some of the adults, pursued projects in the community, such as drainage, cleaning water springs, and building latrines.

Civics was introduced into the rural-school curriculum to foster national pride in being part of the nation. To this end, the Haitian flag was placed in the courtyard of each school, and the students were led in singing the national anthem every morning at the start of the school day. The importance of creating a distinctive, authentic, original Haitian culture that sought to unify the disparate segments of society was stressed, and so Haitian folklore, music and art were added to the school day. Whereas Creole had been used in the lower elementary grades in the oral teaching of agriculture, health, manual arts, and elementary arithmetic, except in the last two most advanced grades, all written work had been done in French. The goal now was to increase literacy and facilitate schoolwork in general by having all the academic work, written and oral, in the first two or three grades of the rural schools conducted in Creole. This allowed the vast number of rural children, who were non-French speakers, to understand what they were being taught and to provide a comfortable and gradual bridge to their subsequent studies in French.

All the incompetent instructors were fired and replaced with those chosen through educational credentials or competitive exams. A cadre of civil-service specialists was created who would remain a constant in and carry on the work and progress of the Division of Rural Education, regardless of who was at the helm. This would be possible because one of Dartigue's most important reforms was to ban political patronage from the Division, allowing educators to obtain and maintain their positions through competence and experience. There was no question of reforming rural education on a scientific and practical basis without specialists in this field with a proper preparation not only in education and the science of education but in sociology and educational psychology. Grants for overseas study (mostly in the United States but also in Canada and Puerto Rico) were arranged to permit teachers, principals, directors, statisticians and the like to complete and perfect their education and training. A new type of teacher training (pre-service and in-service training, plus summer courses) was developed, and new methods in teaching a new curriculum were introduced that allowed for a practical education that would instruct rural students in the basics of agriculture and manual training, along with the three Rs.

Many of the schools were in very bad physical condition. The best accommodations that could be found in each community were rented to house the schools, based on suitability and not on favoritism as in the past. Others were repaired while some were built from scratch by teachers and students pitching in together. School furniture was made or repaired, mostly in the shops of the farm-schools, thus providing the teachers and pupils of these institutions with a chance to engage in practical and useful projects. Essential school materials (e.g., blackboards, pencils, chalk, books, paper) were distributed. Mobile teams were created to go into the countryside to assist teachers; refresh their knowledge, teaching methods and curriculum; and reinforce the feeling of being part of the Division of Rural Education from which they were geographically isolated. The teams also discussed local problems with the teachers and tried to help them arrive at solutions.

There was throughout Haitian society a strong stigma attached to manual labor which Dartigue sought to remove by encouraging the pursuit of vocational skills in trade schools and to develop an appreciation of the value of farming (given Haiti's largely agrarian society). Before 1932, the teaching of trades and agriculture was absolutely unknown in the rural schools. At the end of the academic year 1934–35, trades were practiced in all the rural schools at least some of the year. A special supervisor of manual trades and two supervisors of agriculture were sent to the various districts to help the local supervisors. Having a manual skill would be enriching to the peasant and would widen his horizons; it would also give him something with which to occupy himself in the dry season and would be a source of added revenue.

From 1936 on, there began in earnest a campaign of reforestation to counteract the indiscriminate felling of trees for charcoal (a truly catastrophic situation today) through the designation of an official Arbor Day that involved the planting of trees. Teachers attended courses in the subject, including the causes of deforestation, that they then transmitted to their students.

Beginning in 1931, major changes were made in the way rural education was structured. The National Service of Agricultural Production and Rural Education was divided in two, with one part being a reorganized Division of Rural Education (whose antecedent had come into being with the formation of the farm-schools under the Americans in the 1920s). The Central School of Agriculture, which had closed in 1930 on the heels of a student strike, was now re-opened, installed under the Division, and overhauled, with an agricultural section for the formation of agronomists and an agricultural-teaching section for the preparation of instructors for the farm-schools, the rural schools, and the vocational schools. New programs were devised for both areas and new theoretical and practical courses were added, especially in the agricultural-teaching section. The school's library was also reorganized, and a special section of Haitian literature by Haitians and of books about Haiti was created for the very first time. Not only was this the first time Haitians had an institution like the improved Central School, but it was also the first time they had a national library of such breadth.

At this time, there were three types of rural schools: the 74 farm-schools (under the Department of Agriculture), roughly 365 national rural schools (administered by the Department of Public Instruction), and 160 religious schools (nominally under the Department of Public Instruction, with 130 subsidized by the State) that had been set up in certain parishes per the Convention of 1913 between the Government and the Catholic bishops. The national rural schools were moved to the Division of Rural Education, which also oversaw the farm-schools. Finally, all of rural education could be found under one roof.

The farm-schools had been the first serious and successful attempt to devise a kind of rural school to meet the needs of the people of the rural communities. They emphasized not only literacy but social services and the study of adequate methods of agriculture and handicrafts. The schools were now enlarged and ameliorated, and they functioned far better than they had before. Each school – consisting of a good building of one, two, or three classrooms – had a garden plot and a shop room equipped with the necessary tools and implements. Teaching methods were improved, and incompetent instructors were gradually dismissed, replaced only by those who had studied at the Central School of Agriculture. Up until now, Haiti had never had a corps of indigenous teachers having a classical and professional preparation; presently, with the instructors of the farm-schools, it did.

The American Occupation had, in 1928, set up a small but important post-primary boarding school at Chatard in the north where outstanding pupils from the other farm-schools who had completed or were about to complete elementary schoolwork were sent. They remained at Chatard for three to four years and received advanced academic training as well as agricultural and manual training. Some of the boys did so well that, at the end of their studies at Chatard, they were able to go through the teacher-training division of the Central School of Agriculture. This was the very first attempt made to train rural leaders.

In 1935, one hundred twenty-six primary schools in 63 bourgs (small market towns on a rural economy) were transferred to the Division of Rural Education. Then, in 1938, some 100 communal schools (maintained by a certain number of municipalities) and 10 schools (five for boys and five for girls) in the five agricultural colonies (on the border of the Dominican Republic) were also added to the Division. All of these underwent thorough reorganization, with the hiring of more qualified teachers (again through competitive exams), finding better housing for schools, and providing proper furnishings and school materials.

In 1939, President Sténio Vincent created a special school in Cap Haïtien, the Children's Home of Vocational Education (a loose translation of La Maison Populaire de l'Education), a sort of primary technical school for less privileged boys, which was placed under the Division of Rural Education.

That same year, a girls' school modeled on the one for boys at Chatard was finally realized: Martissant was created outside Port-au-Prince, a post-primary domestic science school for 100 girls, with all expenses paid by the government. It was the first of its kind and a real achievement. It too was run by the Division.

Yet between 1935 and 1941, the annual government-allotted budget for rural education kept shrinking, which meant increasing creativity and careful management on the Division's part in utilizing available funds.

Between 1942 and 1945, the 4C Associations (standing for coeur, cerveau, corps, et conscience — that is, heart, mind, body, and conscience), begun a few years earlier and patterned after the American 4H Clubs, were taken over, reorganized, and developed into one of the most interesting features of the work in rural schools. They were gradually extended to a large number of schools, and by the end of 1944, there were more than 250 with 4C Associations. Their members were pupils who were enrolled in a given school and who adopted a yearly program of work consisting of a number of projects. Each group of projects was under the special care of a particular committee: agriculture, animal husbandry, health, manual arts, beekeeping, etc. It was felt that the habits and attitudes developed through these activities would be made more permanent if the initiative and the responsibility for the undertaking and carrying through of some of the projects were left to the pupils themselves under the guidance of the teachers. The agriculture committee, for example, was in charge of the upkeep of the grounds and gardens and supervised the agricultural projects launched in the community. The health committee took care of the cleanliness of the school premises and promoted extension work in the communities.

Some rural-school teachers held night classes to teach literacy among adults, but they were faced with a language problem. The peasant knew only Creole, whereas books and printed materials had been in French. In 1940, an Irish Methodist preacher, the Reverend H. Ormonde McConnell, had initiated in the Port-au-Prince area two or three centers experimenting with teaching reading in Creole. In 1943, Dr. Frank C. Laubach, a former American missionary who had developed alphabets and phonetic methods for writing various dialects and languages, came to Haiti and helped the Rev. McConnell improve his phonetic method. After a few demonstrations, the Department of Public Instruction appropriated a sum of money to continue the experiment on a wider scale under the direction of a Literacy Committee which was headed by the Director of Primary Education (in the Department of Public Instruction) and of which the Rev. McConnell was made a member. Two booklets, teaching materials, and a small weekly newspaper were published in Creole. (Each issue of the paper reached 5000 copies.) Literacy centers were established in a number of localities throughout the Republic with the help of volunteers. At the end of 1944, reports indicated that 4242 adults had attended the various centers and that 1946 had been taught to read.

Urban Education

Unlike rural education and vocational education, which had been under the Technical Service and the Department of Agriculture during the American Occupation, urban education had been administered by the Department of Public Instruction and had not seen any reform during the 1920s.

The urban primary schools were in two sections: elementary primary education, lasting six years, and higher (or superior) primary education, lasting an additional two to four years. Secondary education consisted of eight national lycées (high schools), three private religious academies, and six lay secondary schools, all for boys, as there was still no secondary school for girls. The curriculum ran for seven years.

The Minister of Public Instruction's report to then-president Sténio Vincent for the year 1932–1933 spoke of the stagnation of the urban schools, which was due principally to the absence of sufficient funding. Teachers' salaries were low, making it difficult to recruit new instructors, despite the burning need. Inspectors and deputy inspectors were unable to make the three annual tours of their districts as required by law. School buildings were unsatisfactory because of age, neglect or unsuitability for housing classrooms. Basic school furniture was in need of repair or replacement, and school supplies were often non-existent. Student attendance had not varied over the course of years, since the law governing compulsory education was not enforced. Moreover, students were turned away from some schools because there was no room for them or there weren't enough teachers. Promising plans for a normal (i.e., teacher-training) school for women instructors of primary education had not progressed very far, and the recently created normal school for male teachers, housed in the basement of the newly formed National Service for Vocational Education, had yet to be properly organized. Both the women's and men's facilities lacked a dormitory to lodge applicants from the provinces.

The shortcomings experienced at the primary level naturally affected the quality of urban education all the way up the line: insufficient formation in the lower grades left students less prepared for what they would encounter in high school. But the secondary level came in for its own criticism from The Report of the United States Commission on Education in Haiti overseen by Robert Russa Moton, principal of Tuskegee Institute, and issued in 1931, for failing to provide for the needs of the country by focusing on the literary at the expense of science, the social sciences, sociology, government, and economics.

The dozen urban vocational schools (nine for boys, three for girls) were also at a disadvantage because the men best qualified and trained in the field by the Americans unfortunately did not head the new National Service of Vocational Education, and the schools, with the exception of Elie Dubois, degenerated further, until they were reorganized once more, in 1943. However, around 1935, a modern trade school, well equipped with shops and a dormitory, was built in Port-au-Prince and placed under the direction of the Catholic Salesian Fathers (Salésiens de Don Bosco).

Also in 1935, Résia Vincent, the president's sister, brought from Italy five Salesian Sisters of St. John Bosco/Daughters of Mary Help of Christians (Soeurs Salésiennes de Don Bosco/Filles de Marie-Auxiliatrice) to run a boarding school that she opened in the poverty-stricken area of La Saline, just outside Port-au-Prince. It accommodated 100 very poor orphaned girls who were to be trained to become maids, cooks, housekeepers or seamstresses by learning, in addition to the three Rs, cooking, cleaning, laundry, sewing, and other household tasks. Ms. Vincent hoped to give girls a proper preparation, provide them with a trousseau upon leaving, and have them placed in families that would treat them well (which was not always the case with domestic help). As such, it was the first of its kind. Ms. Vincent then created a leisure club known as Thorland, outside the capital, whose dues and other income would support the school, and asked Esther Dartigue to be its director.

In 1938, a first attempt was made to reorganize the Department of Public Instruction. The system was split into two big divisions: Urban Education and Rural Education, while Vocational Education ceased to exist as a separate entity and was shifted from the Department of Labor to the Department of Public Instruction.

Urban Education had three sections: Administrative, under a Director-General; Pedagogic, with an Assistant Director of Classical Education, an Assistant Director of Vocational Education, and an Assistant Director of Girls' Education; and an Inspector Service. A Central Bureau of physical education was also created, consisting of a Commissioner of Sports, two monitors and a doctor. A dormitory was added to the Normal School for Girls for students from beyond the capital city, allowing for more young women to attend the school and for more trained staff to return to the provinces. In a certain number of provincial schools, incompetent teachers were replaced by students and graduates of the Normal School.

Although the new administrative and organizational set-up constituted a definite improvement over the old one, and the men in charge more experienced, nevertheless it did not meet the professional and administrative requirements of an institution qualified to be entrusted with varied and specialized functions. It lacked professional training and dynamic leadership at the top, as well as the trained personnel needed at the intermediate levels. By the end of 1939, the reorganization movement had lost its momentum, and subsequent to a change in the Cabinet, no further measures were taken.

In May 1941, a new government, headed by President Elie Lescot, undertook a thorough reorganization of urban education under Maurice Dartigue, the newly appointed Minister of Public Instruction, Agriculture and Labor. The changes made would become known among subsequent and present-day educators as la réforme Dartigue (the Dartigue reforms – see, for example, Charles Pierre-Jacques' From Haiti to Africa, Itinerary of Maurice Dartigue, a Visionary Educator, published in 2017). As in the earlier case of rural education, there would be many firsts in the urban field, and they would be preceded by a complete, objective and scientific survey of the Department, from the central office to the most remote school. The initial survey was of the primary schools, followed by one of the vocational schools and, lastly, one of the secondary schools. A full inventory of conditions in each school was made, and a questionnaire was filled out by as many teachers as could be found. From a knowledge of existing conditions, based on fact and statistical data, a reorganization and modernization of the urban school system could proceed.

The reorganization took place in three phases over the course of three years, inaugurating (a) a new administrative organization, (b) the training of personnel, and (c) the reorganization of the curriculum, improvement in methods of teaching, the editing of textbooks, organization of social welfare, and training in citizenship.

Administration and supervision were centered in the Division of Urban Education (Direction générale de l'enseignement urbain), which was reorganized and installed under a Director-General with the following specialized divisions: Primary and Normal Education, Vocational Education, Secondary and Higher Education, Physical Education, and the Central Administrative Division. This last was constituted as follows: a personnel section which housed records on all teachers and kept a check on appointments, transfers, promotions, and pension requests; a statistics section; an inventory and supply section; and an accounting and control (of all purchases) section. An engineer was placed in charge of the upkeep of school buildings. From 1942 to 1945, an annual report was regularly published, covering all phases of the work of the Department of Public Instruction, with statistics and a summary of expenditures properly classified.

Primary-school teachers who did not have the equivalent of nine years of primary education and had not obtained a passing grade in the examination given to them were dismissed. Candidates for teaching posts without a diploma from a normal school or a teacher-training course or without a certificate of completion of their secondary education were employed only if they passed a competitive examination. Short regional courses on the principles of education, methods and administration were inaugurated for all primary-school teachers in service. Summer courses for improving skills were introduced, held for one month at Damien (near Port-au-Prince), and were continued the next three years.

In 1942, as a pilot project, Creole began to be used in the first two years of urban primary schools, thus allowing teachers to better initiate into school life children lacking French before introducing French as the language of their education.

The vocational schools, which numbered 10 in 1942 (of which two were for girls) posed greater problems for their reform because these teachers needed to have an expertise in their field right from the start and could have only a certain number of students in class to make teaching effective. Vocational education also required materials that were expensive. A decision was made to close during a period of about 15 months those schools located in the provinces, while five principals and 10 teachers were sent to study in the United States and another group of instructors attended the vocational school of the Salesian Fathers in Port-au-Prince for a period of about seven months, where they received an intensive training. Those teachers who were truly incompetent were let go. It was also important to determine the needs of every community so that vocational schools could provide the appropriate courses to their students. The trades taught were cabinet-making, automobile mechanics, masonry, tinsmithing, tailoring, and shoemaking in the boys' schools; cooking, sewing, dressmaking, embroidery, and other needlework in the girls' schools. Not all the schools taught all the trades.

On the heels of the survey of vocational schools, it was realized that the value of the graduates of the four private commercial schools, consisting of 400 students and located in Port-au-Prince, where bookkeeping, shorthand, and typing were taught, did not fully answer the need for competent personnel for businesses. A close collaboration was now established between the Department of Public Instruction and the schools' directors that would allow the Division of Urban Education to organize and direct the schools' final exams.

In some of the larger cities, there were also part-time schools (écoles de demi-temps) established specially for young servants, allowing them to go to public school when they were not working (assuming households would permit their attendance).

As to the secondary schools, they too were in a woeful state. The comprehensive survey carried out by the Department had several aims. One was to professionalize education by hiring competent personnel through competitive exams or proper credentials. The other goal was to become aware in a detailed way of the functioning of the lycées; the method of recruiting staff and the efficiency of this staff; the state of the school premises, the furniture and materials; and generally how the schools were being run. It also became evident that there was a need to create a meaningful program of study and to modernize teaching methods.

Those instructors who did not have a certificate of completion of their secondary-school studies (representing about 10% of the teaching staff) were dismissed, and a prospective teacher who lacked training above the secondary-school level in the subject he was to teach could be employed only after passing a competitive exam. Furthermore, during three consecutive years, all the teachers of the nine public lycées of the Republic had to attend summer courses in Port-au-Prince. (Teachers of private secondary schools were invited to attend as well, and some accepted.) These courses, which were an all-important innovation, were taught by visiting professors from American, Canadian and French universities, as well as by Haitian academics. (Among the scholarly figures Maurice Dartigue attracted to Haiti to lecture or to teach specialized courses to Haitian instructors were the eminent W.E.B. Du Bois, civil rights activist and co-founder of the NAACP; Aimé Césaire, co-founder of the Négritude movement in Francophone literature and French National Assembly Député representing his native Martinique; Alain Locke, "Dean" of the Harlem Renaissance and philosophy department chair at Howard University; and Auguste Viatte, literature department chair at Laval University in Montreal and champion of the French language throughout the world. Dartigue was also one of the lecturers at the summer courses.) The Americans were sent by the Division of Cultural Relations of the U.S. State Department and the U.S. Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs. These departments also provided for a period of about three years a group of American teachers to teach English in the different lycées and to train a group of Haitian teachers of English. The supervisor of this group, former Howard University professor Dr. Mercer Cook, did an outstanding job. DeWitt Peters, another of the American teachers, opened, with the Department of Public Instruction's financial support, the Art Center (Centre d'Art) in Port-au-Prince, which had considerable success and launched Haitian art onto the world market.

Dorothy M. Kirby, yet another of these Americans, became the principal of the first public lycée for girls since the time of President Alexandre Pétion's secondary school for girls that had closed shortly after his death, in 1818. The opening of this new school in the fall of 1943 was a momentous event. Forty girls were admitted to the lycée which had the same curriculum as the boys' school, but with domestic science and child care added. Since then, hundreds of young women have become professionals, especially in the fields of medicine, education, law, architecture and engineering.

The Normal School for Girls was closed for five months, reorganized and re-opened in a new environment. In this project, the Department received the cooperation of the U.S. Inter-American Educational Foundation (part of the U.S. Institute of Inter-American Affairs). A teacher-training section for male teachers of urban schools was added to the Rural Normal School at Damien.

In addition to these reforms, Dartigue sought to address the matter of personnel. Laws were passed and regulations instituted establishing the qualifications for the different levels of instruction and the positions of the professional staff. Moreover, political patronage was banned, a decision of capital importance that applied to all branches of the Department, not just to teachers, and where promotion would be based on merit and seniority. This was a radical departure from prior administrations where the field of education had been viewed as fertile ground for politicians to exercise their muscle in getting jobs for friends and family, regardless of qualification. This was because government jobs were practically the only secure means of livelihood for a large part of the educated class, since industry was essentially non-existent, since almost all the agricultural production was in the hands of an illiterate peasantry, and since a large part of commerce was controlled by foreigners. The successful reorganization of urban education was dependent on the development of a professional and administrative staff that was independent of politics. And for four-and-a-half years, there was no deviation from these rules. For the first time since Independence, a Haitian government would have in a serious manner laid down the bases for the professionalization of urban education. This was a brand-new conception in the field, the most remarkable and important contribution the Government made to the Department, allowing for permanent cadres of education and administrative specialists capable of assuring not only the application of reforms but also their continuation into the future, for one of the leading causes of the inefficiency of the Department, aside from politics, had been the absence of a body of competent specialists capable of directing and controlling the diverse branches of education. Specialists in the science of education and in educational administration are necessary to resolve the different problems that arise at every level of schooling.

But where to find the first of these all-important specialists for the central office and for field supervision? The problem was solved using a few already experienced and professionally trained men from the Division of Rural Education and from the former National Service of Vocational Education, and then training others. Moreover, a number of men and women were selected from the Department of Public Instruction and sent abroad on grants for a period of training, varying from one to two years. In the first year alone (between June 1941 and October 1942), more than 80 students were dispatched to the United States, Puerto Rico, Canada and France, and the numbers only continued (more than 200) over the next three years. The majority went to the United States, to study education, especially the following branches: primary, secondary, vocational, physical education, administration, statistics, the teaching of English, and the teaching of music. The aim was to increase their competence and professionalism. About 95% of those receiving grants were chosen among teachers, supervisors, directors, principals, administrators and statisticians already in service, and some 15% attended Columbia University, which played an important role in educating Haitian students, helped and mentored by Mabel Carney, head of the rural education department. During this same period, about 150 other students traveled abroad, mostly to the U.S., to study in various other fields, including law, sanitary engineering, public health, military sciences, architecture, civil engineering, economics, agriculture, veterinary sciences, labor inspection, anthropology, social insurance, and various trades.

According to the facts revealed in the comprehensive survey, nearly 50% of school locations were in horrible condition, and the best rooms in these schools were often used not as classrooms but as residences for the school directors and teachers. Almost all the State school buildings were rehabilitated. Schools housed in rented buildings were moved to better quarters. Small schools in one town or in a section of a town were consolidated into larger and more efficient units, and there were some new buildings as well. The Standard Fruit and Steamship Co. generously undertook to erect a building to house the Lycée Saint-Marc, and O.J. Brandt, a British industrialist of Jamaican origin living in Port-au-Prince, also generously donated $10,000 for a laboratory building, inaugurated in 1945, at the Lycée Pétion; this was the first private-sector donation to the public sector. About four acres of land were purchased in the middle of the capital city for a new girls' lycée, and by the end of 1945, approximately $14,000 had been saved up to be put toward the construction cost.

The survey also indicated that special attention needed to be given to the appalling condition of school furniture. Consequently, old furniture was repaired, and new furniture such as desks and benches was added to all the schools. Almost all the blackboards had to be blackened. School materials (e.g., pencils, books, chalk, paper and blackboard erasers), which had often been non-existent, were now provided. New or repaired machines and tools were supplied to the vocational schools, which prior to this administration had had practically none.

A new curriculum and new methods of teaching were introduced. Students were encouraged to engage in reflection and real understanding of subjects taught, rather than in "brain cramming." Furthermore, they needed to embrace as quickly as possible the techniques and methods used in the technological civilization of the era. As a result, the teaching of natural sciences was improved and reinforced in the secondary schools, as was the teaching of social sciences and modern languages (English and Spanish). In fact, the reorganized study of English, which was made mandatory, was considered one of the Department's most important achievements. A course in Haitian literature was added. Programs in folklore, music and the arts were inaugurated, helping to develop and promote Haitian culture that would blend together the country's roots with elements of its French heritage and borrowings from its neighbors north and south, with which cultural exchanges were inaugurated, as well as a study of their geography. Calisthenics (which had been extra-curricular prior to October 1941) were now compulsory. Circulars were sent to teachers in all the urban schools showing them how they and their students were to do these exercises. Team sports and recreational games were made part of the school program. Civics was introduced into the curriculum of all primary, vocational and secondary schools to instill pride in being Haitian. For the first time since Independence, the nation's flag appeared outside each school, and the students sang the national anthem every morning. Arbor Day was also celebrated every May. A doctor was assigned to each school to inspect infirmaries and provide examinations of teachers and students. Libraries in the country's leading cities and towns were improved. This included placing the National Library (Bibliothèque nationale) in Port-au-Prince under the control of the Division of Urban Education and installing a new director. Moreover, a special section devoted to Haitian literature by Haitians was inaugurated. All these many changes allowed for order and discipline in the administration and functioning of the education system.

The establishment of a University of Haiti had been voted upon by the legislature as far back as 1920, but no plan had been put into motion. More than 20 years later, steps were finally taken towards its organization. The Law School became the Faculty of Law, and it was given a new director. The laws and rules of admission of students, exams, etc., were strictly observed. The library was organized on a serious basis, both in furnishings and in books and publications. A new Faculty of Sciences was formed, to which were annexed the School of Engineering and the School of Surveying. A new law was then passed inaugurating the University of Haiti, with Dartigue named as Acting Rector (in addition to all his ministerial responsibilities), and stating the general rules for its organization. The Faculty of Medicine and the School of Agriculture, which were not under the direct administration of the Department of Public Instruction, were "affiliated" with the University, and the Dean and Director of these respective institutions became members of the University Council of Deans (Conseil des Doyens). A cultural agreement was signed with the French Government providing for a French Institute (Institut français en Haïti) in Port-au-Prince, which would place a number of French professors at the disposal of the university without cost to the Haitian Government. (This followed the establishment in 1942 of the Haitian-American Institute to promote better relations between the two countries, a program of educational cooperation that would furnish American specialists to teach in Haiti and to improve the Haitian educational system. Furthermore, it provided grants for Haitians to study in the U.S. and Puerto Rico.) Plans were made to include in the university a teacher-training program for prospective secondary-school teachers. At the time of the enactment of this law, a site close to the Faculties of Law and Medicine was acquired at a cost of $9000, and an architectural contest was held to design a University Center with an administration building, library, auditorium, and small dormitory with a cafeteria. After the prizes had been given out for the contest, there was, in December 1945, about $15,000 on deposit for the project, more than necessary to cover the cost of the Administration Building. (Subsequent to Dartigue's exit from the government, the money was never spent for its intended purpose.)

Duvalier Era

Between 1960 and 1971, 158 new public schools were built. Private education represented 20% of school enrollment in 1959–60.[6] After his son Jean-Claude "Baby Doc" Duvalier took over in 1971, the public sector continued to stagnate, but the private sector accelerated partly due to a rule instituted by Baby Doc that religious missionaries were required to build an affiliated school with any new church.[31] By 1979–80 57% of enrollment in primary education, and 80% in secondary education was private.[6] During the Duvalier era a number of qualified teachers left the country to escape political repression.[6] During the 1980s, the average annual growth rates in private and public enrollment were 11% and 5%, respectively.[6]

Post Duvalier Era

The expansion of private schools increased further after the end of the Duvalier regime in 1986, as many religious communities established their own educational institutions. The years 1994–1999 were a peak period for school construction and the private sector has been growing exponentially since.[31]

Twenty-first century

Overview

Though the Constitution requires that a public education be offered free to all people,[32] the Haitian government has been unable to fulfill this obligation.[33] It spends about 10% of the federal budget on the country's elementary and secondary schools.[34] Out of the 67% enrollment rate for elementary school, 70% continue on to the third grade.[35] 21.5% of the population, age 5 and older, receive a secondary level education and 1.1% at the university level (1.4% for men compared to 0.7% for women).[36] Nearly 33% of children between the ages of 6 and 12 (500,000 children) do not attend school, and this percentage climbs to 40% for children ages 5 to 15 which accounts for approximately one million children.[36] The dropout rate is particularly high at 29% in the first basic cycle.[36] Close to 60% of children drop out of school before receiving their primary education certificate.[36] Of the two million children enrolled in the basic level, 56% are at the required age for the first cycle (ages 6 to 11).[36] While the mandated age for entering grade 1 is 6, the actual mean age is nearly 10, and students in grade 6 are on average almost 16, which is 5 years older than expected.[31] 83% of those ages 6–14 attended school in 2005. These rates are much lower for the poor.[31]

With the exception of higher education, private schools in Haiti account for 80% of total enrollments and serve the majority of Haitian students.[37] According to Wolff[37] there are three main types of schools that make up the private sector. The first and largest type of private schools are for-profit private schools run by entrepreneurs. These schools have very few, if any, books and unqualified teachers and school directors. They are popularly known as "écoles borlettes," which translates to "lottery schools," because "only by chance do the children learn anything."

The second type of private schools are those run by religious organizations such as Catholic and Evangelical churches, as well as some nonsectarian schools. The Ministry of National Education at the time of the 2010 earthquake reported that Christian missionaries provide about 2,000 primary schools educating 600,000 students – about a third of the population that is school age.[38] Some of these schools offer a better quality of education than for-profit schools do, but they often have risky conditions and staff with no professional capabilities.

The final type of private school composes of "community schools," which are financed by whatever funds the local community can mobilize. They tend to be of very poor quality, worse than for-profit schools, but they do charge very low fees.

A handful of private schools in Haiti, mostly clustered around the capital city, Port-au-Prince, and accessible to the rich (except for limited scholarship fund opportunities), offer education with relatively high quality standards.[37]

Furthermore, three-fourths of all private schools operate with no certification or license from the Ministry of National Education.[37] This literally means that anyone can open a school at any level of education, recruit students and hire teachers without having to meet any minimum standards.[37]

The majority of schools in Haiti do not have adequate facilities and are under-equipped. According to the 2003 school survey, 5% of schools were housed in a church or an open-air shaded area.[36] Some 58% do not have toilets and 23% have no running water.[36] 36% of schools have libraries.[36] The majority of workers, about 80% do not meet the existing criteria for the selection of training programs or are not accepted in these programs because of the lack of space in professional schools.[36] 6 out of every 1,000 workers in the labor market have a diploma or certificate in a technical or professional field.[36] In addition, 15% of teachers at the elementary level have basic teaching qualifications, including university degrees. Nearly 25% have not attended secondary school.[39] More than half of the teachers lack adequate teacher training or have had no training at all.[39] There is also a high attrition of teachers, as many teachers leave their profession for alternative better paying jobs. Sometimes they are not paid due to insufficient government funds.[40]

Current Issues

Structural violence

Anthropologist Paul Farmer states that an underlying problem, negatively affecting Haiti's education system, is structural violence.[41] He says that Haiti illustrates how prevailing societal factors, such as racism, pollution, poor housing, poverty, and varying forms of social disparity, structural violence limits the children of Haiti, particularly those living in rural areas or coming from lower social classes, from enrolling into school and receiving proper education.[42][43][44] Farmer has suggested that by addressing unfavorable social phenomena, such as poverty and social inequality, the negative impacts of structural violence on education can be reduced and that improvements to the nation's educational standards and literacy rates can be attained.[42]

Educational Disincentives

Education in Haiti is valued. Literacy is a mark of some prestige. Students wear their school uniforms with pride.[45]:5 When Haitians are able to devote any income for schooling, it tends to take a higher proportion of their income compared to most other countries.[45] There is a disjunction between the high opinion of education and educational attainment.[46]

Increasing a family's income would appear to solve the problem of insufficient family funds to pay for schooling.[45]:7In reality, though, there are a confluence of systems and actors in Haiti's educational sphere that need to be taken into consideration.

Locale needs to be considered – depending on whether or not the community is urban or rural.[45]

There are the different actors – students, families, schools, teachers, curriculum, the government, and NGOs. These are briefly some of the issues that affect the various actors:

Students may delay their entry to school. They may be obliged to repeat grades. Sometimes they drop out.[45]

Teachers may be under-qualified.[45]:15 They may be underpaid.[45]:16

There may be insufficient schools in an area. They may lack adequate facilities. The expense of attendance may exceed a families resources.[45] There are some families that spend 40% of their income on school expenses says Education Minister Nesmy Manigat.[47]

Curriculum mismatches may occur. For example, the language of instruction is typically in French. The vast majority of students speak only Creole. French instruction is useful in producing students who will be able to attend a university in a French-speaking country such as France or Canada. There is limited educational opportunities for students who do not want to attend university, or who want to attend but cannot afford it.[45]

The Government provides few public schools. They are vastly outnumbered by private schools. The government is unable to enforce its desired policies with respect to education.[45] This inability has a myriad of ramifications. For example, the Haitian educational system has two exams that the government requires for a student to be promoted to the next grade. These exams are taken at the end of the 5th and 7th grades.[45]:5 :22However, many schools require exams at the end of every school year. The successful result will allow a promotion to the next grade- this includes public as well as private schools.[45]:11

The students are required to pay a fee to take the exams.[45]:29 If the fee is not paid, the student does not pass to the next grade regardless of how well they did during the school year. In rural areas, family income is greatest at the beginning of the school year when the harvest is in. It is easier to have children start school than finish. For families whose children do not get promoted, school fees must still be paid for the grade that is being repeated. This doubles the cost per grade or even more if the exam fees are once more not paid at the end of the year.[45]:5 This scenario is more likely for lower income families who can least afford the increased cost.

A solution to this issue of less family funds at the end of the school year that Lunde proposes is a change in the banking system.[45]:27 She suggests that access to loans at the end of the year based on anticipated harvest of the next year may help in these instances. This is an example of digging deep through a system's issues and coming up with a possible solution that does not appear on the face of it to be connected to the problem.

Another solution to one of the key problems and the main bottleneck[45]:32 – teacher quality and quantity – is using the Diaspora. The World Bank estimates that 8 out of 10 college educated Haitians live outside the country.[45]:15 A way to attract them back to Haiti would be to offer dual citizenship.[45]:15

A number of schools are run by religious organizations but many more are run as a business to make a profit. "The consequence of the privatization of education is that private households are carrying the economic burden of both the real cost of education and the private actor’s profit"[45]:22 Haiti has the highest percentage of private schools than any other country.[45]:22

Repeating grades leads to a wider range of abilities in the classroom, making it that much more difficult teaching. This taxes an already unqualified teacher's abilities. Often teachers are only a few grades ahead of the students they are teaching.[45]:16 Public school teachers typically are more qualified than private school teachers.[45]:15There are no laws or regulations with respect to setting up a school so anyone can do it and begin teaching.

There is a lack of schools in Haiti – insufficient schools given the number of potential students.[45]:17 One of the results of this is that it can be a long walk to school in the countryside, in the dark – a walk one way of 2 hours is not uncommon.[45]:17Parents can be reluctant to send a 6-year-old that far on their own or even an older girl – there are safety concerns.[45]:19If the child does walk a long distance, they are often too tired to pay attention and may even fall asleep in class.[45]:18 The time getting to and from school also cuts into the time to help the family at home. If the parents are relying on the child's labor, this long walk can be a disincentive to enrollment.[45]:19 Delaying school enrollment leads to students starting school overaged which in turn has its own issues.

Schools can be selective about who they admit. A number of them will only admit children who read and write already.[45]:12 This has made a big demand for pre-schools and creates one more hurdle to education for the lower income families.[45]:12 The best preschools cost more than the best private primary schools.[48] Education Minister Nesmy Manigat has set a new policy that disallows preschool graduations - a practice that has been to raise revenue rather than academic standards.[49]

Families use different strategies to provide education despite the disincentives.[45] Parents may focus their educational funds on the one child who appears to be the most promising academically. Or in the interests of fairness, allow one child to go to school, alternating children each year until all have had their chance and then repeat the cycle as funds allow. Since it may take at least 4 years to learn to read and write, dropping out before the first cycle is complete, typically makes an almost total loss of the money spent on that child's education.[45]:29

Given the lack of schools for the number of children who want education, there is a high demand for seats even if a family has the money to pay for school fees.[45]:31 At this point, it becomes a case of who they know – personal connections become necessary. Having connections to a Marraine or Parraine (Godmother or Godfather) who can influence a school's decision to enroll your child is vital.[45]:31 There may actually be a number of influencers in chain – that all must be paid a fee – in order to secure a seat.[45]:31

Impact of 2010 earthquake

_-_Rebuilding_schools_after_the_2010_earthquake%2C_Port_au_Prince%2C_Haiti.jpg)

The 2010 Haiti earthquake that struck on 12 January 2010 has exacerbated the already constraining factors on Haiti's educational system.[31] It is estimated that approximately 1.3 million children and youth under 18 were directly or indirectly affected. Nearly 4,200 schools were destroyed affecting nearly 50% of Haiti's total school and university population, and 90% of students in Port-au-Prince.[50] Of this population, 700,000 were primary school-age children between the ages of 6 and 12 years old. The earthquake caused death and injury to thousands of students and hundreds of professors and school administrators, however the actual number of casualties is unknown.[51] Most schools, including those that were minimally or not structurally affected at all, were closed for many months following the earthquake.[8] More than a year since the earthquake occurred, many schools still remain closed and, in many cases, tents and other semi-permanent structures have become temporary replacements for damaged or closed schools.[52] By early 2011, more than one million people, approximately 380,000 of whom are children, remained in crowded internally displaced people camps.[53]

The Haitian Ministry of National Education estimates that the earthquake affected 4,992 (23%) of the nation's schools.[54] Higher education institutions were hit especially hard, with 87% gravely damaged or completely demolished.[51] In addition, the Ministry of National Education building was completely destroyed.[55] The cost of destruction and damage to establishments and equipment at all levels of the education system is estimated at 478.9 million USD.[56] Another residual effect has been the number of children disabled by resulting injuries from the earthquake. These children are now experiencing permanent disabilities, and many schools lack the resources to properly attend to them.[57]

Successful models

While the Haitian state continues to rebuild the nation's infrastructure following the 2010 earthquake, private institutions are successfully educating Haitians by following a model of solidarity and subsidiarity. The Catholic Church remains the largest provider of education in Haiti, running 15% of schools nationally.[58] The majority of the 2,315 Catholic schools are attached to a parish or congregation.

An example of a successful model is Louverture Cleary School (LCS), a Catholic, tuition-free, co-educational secondary boarding school supported by The Haitian Project, Inc. In 2017, the school achieved a 100% pass rate on Haiti's baccalauréat exam, adding to its historic pass rate of 98%. The school takes a holistic approach to educating talented student's from the poorest neighborhoods in Port-au-Prince and runs an Office for External Affairs to provide job training and support for its graduates. Additionally, the office runs one of Haiti's largest university scholarship programs, providing university support to well over 100 LCS graduates in any given year. As a result, over 90% of LCS alumni are either working or attending university in Haiti. They are sought after employees who earn an average of 15x the per-capita income of Haiti.[59]

Another success is the Haitian Education and Leadership Program (H.E.L.P. )[60] This is a scholarship program which enrolls 100 students per year in Haitian universities and has had significant success in guiding students through university and avoiding brain drain. The university graduate rate for Haiti is 40% but for H.E.L.P. it is 84%. The employment rate is 50% for Haiti but 98% for H.E.L.P. And though only 16% of Haitian university graduates remain in Haiti after graduation, 90% of H.E.L.P graduates remain in Haiti.

Educational system

Formal education in Haiti begins at preschool, which is followed by 9 years of Fundamental Education (first, second and third cycles). Secondary education comprises 4 years of schooling. Starting at the second cycle of Fundamental Education, students have the option of following vocational training programs. According to the Ministry of National Education and Vocational Training (MENFP) education statistics of 2013-2014, there were 3,843,433 students from preschool through the last grade of secondary school (which is called Philo).[61] Higher education follows completion of secondary education, and can be a wide range of years depending on program of study. The World Innovation Summit for Education (WISE) uses data from Haiti's 2002–2003 census administered by the Ministry of National Education and Vocational Training (MENFP),[62] the 2011 Presidential Commission on Education and Training (GTEF),[63] the Haitian Institute of Statistics and Information Technology[64] and the National Institute of Vocational Training (INFP)[65] to provide background information on the educational system in Haiti which is described below.[66]

Primary education

Although not compulsory, preschool is formally recognized for children between the ages of 3 and 5. Around 705,000 children below 6 years of age, representing 23% of the age group, have access to preschool education. The majority of preschools are in elementary schools, and most of these are private and concentrated in the West department. Tuition costs have increased significantly over the last decade for preschools, going from 1628 gourdes (roughly $41) in 2004, to 4675 gourdes (roughly $117) in 2007, a 187% increase in just 3 years.