Education in South Sudan

Education in South Sudan is modelled after the educational system of the Republic of Sudan. Primary education consists of eight years, followed by four years of secondary education, and then four years of university instruction; the 8 + 4 + 4 system, in place since 1990. The primary language at all levels is English, as compared to the Republic of Sudan, where the language of instruction is Arabic.[1] There is a severe shortage of English teachers and English-speaking teachers in the scientific and technical fields.

History

Pre-South Sudanese Civil War

Roots of the recent Civil War

The recent 2013 South Sudanese Civil War that resulted in a division of the state of Sudan dates back to Second Sudanese Civil War, which was a national conflict between the majority Muslim, Arab northern leadership administration and Christian, African South.[2] With the limited social services destroyed, hundreds displaced, and educational facilities closed, the implications for education increased significantly. These consequences extended to relief operations, as finding individuals with an adequate level of schooling and education to be trained as health relief workers became more difficult with time.[2] After 5 years, in 1998, a total of 900 schools emerged in rural areas owned by the Sudan People's Liberation Army in southern Sudan. These schools were facilitated by local communities and guided by relief wings in the Sudan Relief and Rehabilitation Association (SRRA) and the Relief Association of South Sudan (RASS).[2]

Creation of the Education Coordination Committee

There was very limited support given to schools in most areas of southern Sudan up to 1993. While some individual NGOs as well as UNICEF offered some training materials for classes, most of the external development efforts were decentralized. As a result, the Education Coordination Committee (ECC) of the Operation Lifeline Sudan (OLS) in southern Sudan was established to consolidate the diverse efforts not only to better education in the SPLA-held areas in southern Sudan but also to support existing education structures under the SRRA and RASS.[2] The priorities of the ECC were centered on teacher development and are summarized below:[2]

- Increasing the level of education received by teachers and further supplementing it with professional training. This contributed to a focus on teacher education rather than solely teacher training.

- Improving the quality of education and training. The desire to invest in this improvement stemmed from the realization that teachers who were properly trained in previous iterations were able to re-emerge and contribute even after geographic displacement and were better suited to the volatility of the region that threatened stability and consistency of education and even physical destruction.

- Bringing the attention of teachers toward important issues like health, female education, and psycho-social needs of students is significant for development post-conflict.

Impact of the Education Coordination Committee

The establishment of the above priorities directed the ECC's focus towards standardization of education and quality training for teachers. The ECC developed a modular teacher-education scheme that operated at five levels, each involving a two-to-three-week course in Sudan that covered both academic and vocational topics.[2]

In terms of content creation, the ECC's materials for distance education has been written by southern Sudanese educationists, or those who have a great deal of experience in the region.[2] Textbooks for the trainings have also been created for these teacher-education courses and have been written in English as well as in local languages.[2] After the creation of these books, the ECC held a workshop to introduce 60 senior educators to the course textbooks. These individuals are now coordinators who support other teachers at their schools.[2] Additional training about how to best address psycho-social needs has increased in attention over the years and is an integral part of addressing student needs.

Although schools have been established, they have been created at the local village level, introducing the variability of volunteerism and lack of higher leadership beyond village elders and Parent Teacher Councils.[2] To address this, the ECC has pursued avenues to garner more community accountability and support. Here are a few key ways the ECC has done this:[2]

- Providing seeds and tools for school gardens (600 were given in 1993 and 1994) in order to produce vegetables for teachers and children. Another goal of this initiative was to increase students agricultural awareness.

- Provisioning sewing materials and cloth for women's tailoring groups that can make school clothes for teachers and students. This excess cloth is often bartered, and upon receipt to UNICEF, more cloth is attainable to schools.

Relationship between Civil War, religion, and education

Prior to the recent South Sudanese Civil War, South Sudan was primarily viewed as an impediment to the spread of Islam to more southern African nations. The National Congress Party (NCP), which represented a very fundamentalist Islamic policy and imposed Islam as a dogma on both Muslim and non-Muslim groups, replaced the administrators and teachers from the Ministry of Education. With the NCP in power, the objectives of the national education system shifted to Islamic values.[3] The rejection of rapid Islamization and the shift towards a more Western and modernist educational approach contributed to a cultural dichotomy in the educational systems in North vs. South Sudan. One such example is exemplified in the decision of the Southern Sudanese Ministry of Education, Science and Technology to mandate English as the primary medium of instruction for the first three years of primary school, which has made the integration of Northern Sudanese very complex and introduced linguistic barriers.[3]

The civil war in Sudan was fueled in part by the systemic denial of education in South Sudan. Due to the stark religious differences in Sudan, with Islam being more prevalent in the North, students in South Sudan are disproportionately equipped to take the national examination after reaching the eighth grade.[3]

Education landscape

The educational landscape prior to the South Sudanese Civil War can be observed in these statistics from the Ministry of General Education and Instruction:[4]

Primary School:

- There were greater than one million eligible children who had not been enrolled in primary school.

- The primary school dropout rate hovered around 23 percent.

- Only 6 percent of all eligible 13-year-old girls completed primary school education. Along the line of pronounced gender inequalities that surfaced even in primary school education, it was noted that South Sudanese girls were twice as likely to pass away during childbirth than complete their primary school education.

Secondary School:

- Among teens who are eligible to enroll, total enrollment in secondary school is under 10 percent.

- The secondary school dropout rate was around 61 percent.

Women

According to UNESCO, as of 2017, the number of illiterate individuals older than 15 constitutes more than 70 percent of the population in South Sudan.[5] The challenges are particularly severe for female children. According to the 2010 South Sudan Household Health Survey, the nationwide literacy rate for women remains to be 13.4 percent.[4] According to UNICEF, fewer than one percent of girls complete primary education. One in four students is a girl and South Sudan maintains the highest female illiteracy rate in the world.[6] It is estimated that more than one million of children eligible for primary school are not enrolled, with secondary school enrollment being even lower than 10% among those eligible.[4]

Effects of the Civil War on education

Due to the longevity of the Sudanese Civil War conflict, which consisted of three sub-conflicts and spanned almost 50 years, only about 30% of 1.06 million eligible students were enrolled in primary schools in South Sudan.[3] According to the Ministry of General Education and Instruction, during the Civil War, educational and health facilities were incinerated and shut down, school teachers evacuated towns or were displaced, and the resulting lack of infrastructure contributed to a generational denial of education to children in the region.[4]

Significance

To enroll in higher education, Sudanese students are required to take a national examination in the eighth rate, and in the North about 78% of students took the examination and even more were enrolled, as opposed to the South.[3]

Considering the historical context of education in South Sudan is relevant because of the systemic denial of educational and economic opportunity for those fighting for independence during the war, as well as lack of viable financial options after the war to access education.[7] With more than 1.5 million persons and 90,000 in refugee camps, improved education is needed to pave the way for greater economic opportunities and reduce South Sudan's reliance on the main industry of oil production.[7]

Challenges

While a peace deal was signed in August 2015, South Sudan's recovering education system still faces a great deal of challenges, exacerbated by social conditions like famine and ongoing violence. Some main challenges are listed below:[8]

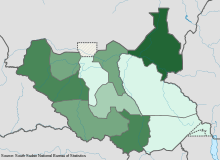

- There are huge location based disparities in education.[9]

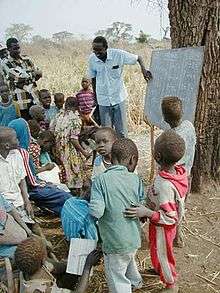

- Schools are under-equipped to accommodate such large numbers of returning IDPs and refugees, and temporary structures like tree covers are used as classrooms.[9]

- A great deal of teachers have not completed primary education themselves.[9]

- Much of the curriculum taught in South Sudan has been used in Uganda, Kenya, and Khartoum government, so there is little to no organic, unified curriculum developed in the region.[9]

- English is the primary language of instruction but as observed in the history of the region, most of the children have only been taught Arabic and thus understand very little English.[9]

- There are very few post-secondary schools and technical institutions that teach vocational skills.[9]

Teacher training and development in South Sudan

Post Civil War, education in South Sudan has largely had a focus on peace-building, from integration into early childhood programs to secondary school programs for students who are and are not formally enrolled in school.[4] Many school teachers have requested training and support to engage topics of anger management, guidance, counseling, peace education, and life skills with children afflicted by the war.[4]

The Ministry of Education, Science and Technology has supported these efforts, granting permission to administrative staff including 30 teachers with equal male and female representation from 15 schools in Juba, and faculty members from the University of Juba to attend peace-building courses in the area.[4] To meet the needs of the children they were teaching, the course programming encouraged curriculum development in a conflict-affected context.[4]

With the disruption in education due to cycles of war and political instability, the emotional effects on students extend beyond the classroom. In an interview conducted by Dr. Jan Stewart, a researcher of psychosocial support in education for children experiencing post-conflict in northern Uganda and South Sudan, a 16-year-old female student explains,

On my part as a student, the conflict affected me internally and also in my studies . . . the schools were not opened on the set month of February . . . our teachers . . . some got injured till now are in hospitals and others died so suddenly and sad . . . people moved to other countries so our population is very low and who will take care of this three-year old nation . . . I live in fear and sadness because anytime disagreements may occur and that really makes pain and sadness.[4]

Challenges with teacher training

After the conflict, many of the teachers who returned to schools faced a wide array of challenges: no pay, inadequate access to resources, overcrowded classrooms, deterioration of facilities, etc. Many of the teachers are also forced to assume the role of a caregiver to students who lost their parents in the war.[4] Without any kind of substantive post-trauma protocol embedded in the existing curriculum, teachers are tasked with attaining support from the Ministry of Education for appropriate renumeration, student-focused leadership, and consistency among different educational policies and practices to address both student needs and mental health issues for those working in this space.[4]

Primary education

As of 1980, South Sudan had approximately 800 primary schools. Many of these schools were established during the Southern Regional administration (1972–81). The Second Sudanese Civil War (1983–2005), destroyed many schools, although the SPLA operated schools in areas under its control. Nevertheless, many teachers and students were among the refugees fleeing the ravages of war in the country at that time. Today many of the schools operate outside in the open, or under trees, due to lack of classrooms. Primary education is free in public schools to South Sudanese citizens between the ages of six and thirteen years.

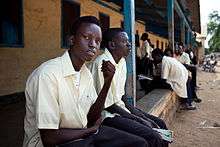

Secondary education

Secondary school has four grades: 9th, 10th, 11th and 12th. In secondary school, science subjects are introduced, including chemistry, biology, physics, geography and others. The students ages are about 14 to 18 years, while in secondary school. There is a particularly high drop-out rate in secondary school; due to truancy among boys and pregnancy among girls.[10]

Post secondary education

After graduation from secondary school, one can pursue further education in either a university or a vocational (technical school). There is a shortage of both, but more so less technical schools than the country needs. Like in most sub-Saharan countries, too much emphasis is placed on acquiring a university education and not enough on obtaining life-sustaining practical skills in a vocational or technical institution.

Environmental education

Relevant environmental issues

There are a number of environmental issues in South Sudan, the most notable being drought, exacerbated by famine and caused by desertification and losses in crops, vegetation, and livestock.[11] Drought has compounded into a host of other problems: failure of crops, decline in productivity, shrinking food reserves, and hunger and malnourishment. The effects of these problems have been disproportionally felt by women and children, and education has largely been viewed as a crucial element of the solution.[11]

Environmental education for women

To offset these impacts, Sudanese environmental adult education engages women in the process of selecting the most nutritious foods with local fruits, vegetables, and plants as well as informing a curriculum that teaches the causes and effects of environmental degradation in Sudan. This is driven by the idea that women have the ability to leverage their indigenous ecological knowledge and experiences to drive socio-environmental change.[11]

An example of this is the Joint Environment and Energy Programme (JEEP) in the neighboring nation of Uganda, in which women environmental adult educators assist other women in working with fuel wood conservation technologies including fuel-saving stoves, tree planting agroforestry, and the conservation of soil and water via organic farming.[11] Similarly, in South Sudan, the Ministry of Energy partners with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to create fuel-saving stoves.[11] Some benefits of this ecological literacy include women gaining skills in organic, marketing, and traditional farming as well as food production, thereby creating a "knowledge forest".[11] Such classes have not only equipped with South Sudanese women with the skills necessary to increase production and thus sales of food but also encouraged them to enter leadership roles in their respective communities and civic educators who have designed their own projects.[11]

Nutrition education

Nutrition education in the Ministry of Health is primarily delivered via the Nutrition Division, a division that educates mothers through health agencies as well as Maternal and Child Health centers.[12] The objective of the Nutrition Division is stated to prevent malnutrition in its clinical stage and treat it through rehabilitation and diet.[12]

The first of these nutrition centers in Sudan was established in Omdurman, and its primary objectives were to take care of children who are in the early or moderate stages of malnutrition and engage their mothers in the process.[12]

Vocational schooling

South Sudan is in desperate need of technical/vocational school graduates in order to build and maintain its infrastructure including: building roads, houses, water treatment systems and sewage plants as well as computer networks, telephone systems and electricity generating plants to power the entire infrastructure. Maintaining those facilities will also require a lot of trained manpower. As of late 2011, there are not enough technical institutions to train the needed manpower.

Universities

As of July 2011, South Sudan has twelve universities of which seven are public and five are private. Officials estimate that about twenty-five thousand students have registered at the five public universities. It remains to be seen how many students do report to campus, now that all of the countries universities are actually located in South Sudan, and not in Khartoum.

The government pays for food and provides housing for students. The former Minister for Higher Education, Joseph Ukel, said at the time finding enough space was one challenge the universities faced. Another issue is money. Ukel said the South Sudanese Government's proposed budget for 2011 did not include any money for the universities. Then there is the problem of teachers. Almost seventy-five percent of the lecturers are from Sudan. They are not likely to move to South Sudan to continue teaching in their former universities, now that South Sudan has seceded from Sudan.[13]

Recent efforts in the reconstruction period

UNICEF

A number of NGOs have been instrumental in increasing the number of educational services in the region, like UNICEF's "Go to School" campaign. After the brief respite in the civil war in 2005, the number of students attending southern Sudanese schools more than quadrupled, with 34 percent female.[3]

In response to the ECC's distribution of sewing materials for schools, in which two-thirds of the cloth is usually allocated to make school clothes for students and teachers, UNICEF provided more cloth upon the validation that the clothes have been made and received by individuals in that school.[2]

UNICEF has also supplied basic education materials that individuals are not able to purchase in South Sudan in the form of "Education Kits," which contain items such as chalk, pens, pencils, exercise books, and a football.[2]

The UNHCR has directed efforts to creating optimal conditions for the reintegration of Sudanese refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) by constructing and expanding schools and training centers and supplementing classes with educational materials.[14] In addition, the UNHCR has engaged in efforts to train teachers, promote female education, spread discourse about stigmatized topics like peace-building, HIV/AIDS, and gender-based violence (SGBV).[14] Their efforts have been bolstered by 11 physical office locations in key return areas.[14]

Recent education statistics

While the global awareness of education in South Sudan is growing slowly, the larger issue remains that there is an inequitable distribution of learning materials and minimal training for untrained instructors. In 2007, it was measured that there were only 16,000 teachers that taught an aggregate of approximately 600,000 students. Many of the classes occur under a tree, with students totaling more than 100 per class, and limited teaching materials for a majority of the untrained instructors.[3]

Education ministries

There are three cabinet positions in the Cabinet of South Sudan that impact education. Each is led by a full cabinet minister:[15]

- Ministry of Youth Sports & Recreation - Minister: Dr. Cirino Hiteng Ofuho

- Ministry of General Education and Instruction[16] - Minister: Joseph Ukel Abango

- Ministry of Higher Education, Science & Technology - Minister: Dr. Peter Adwok Nyaba

See also

- Educational inequalities in South Sudan

- Government of South Sudan

- List of universities in South Sudan

References

- In 2007 South Sudan Adopted English As the Official Language of Communication

- Joyner, Alison (February 1996). "Education in Emergencies: A Case Study from Southern Sudan". Development in Practice. 6: 70–74. doi:10.1080/0961452961000157614. JSTOR 4029359.

- Breidlid, Anders. "Sudanese Images of the Other: Education and Conflict in Sudan". Comparative Education Review. 54 (4): 555–575. JSTOR 10.1086/655150.

- Stewart, Jan (2017). "MEETING THE NEEDS OF CHILDREN AFFECTED BY CONFLICT: Teacher Training and Development in South Sudan". Children Affected by Armed Conflict: Theory, Method, and Practice: 296–318. JSTOR 10.7312/deno17472.20.

- Kiden, Viola (8 September 2017). "South Sudan still has highest illiteracy rate -UNESCO". Eye Radio.

- Brown, Tim. "South Sudan education emergency" (PDF). FRM Education.

- Radon, Jenik, and Sarah Logan (Fall 2014). "SOUTH SUDAN: GOVERNANCE ARRANGEMENTS, WAR, AND PEACE". Journal of International Affairs. 68 (1): 149–167. JSTOR 24461710.

- Walters, Quincy (20 March 2016). "In South Sudan, A Struggle To Get, And Keep, Kids in Schools". NPR.

- Brown, Tim. "South Sudan education emergency" (PDF). FRM Education.

- South Sudan Experiences High Drop-out Rates In Secondary School

- Tabiedi, Salwa (2004). "Women, Literacy, and Environmental Adult Education in Sudan". Counterpoints. 230: 71–84. JSTOR 42978362.

- Khattab, A.G.H (1974). "NUTRITION EDUCATION PROGRAMMES IN THE SUDAN: A REVIEW". Sudan Notes and Records. 55: 181–184. JSTOR 42677970.

- Doughty, Bob. "South Sudan Works to Rebuild Higher Education". VOA Special English Education Report.

- Brown, Tim. "South Sudan education emergency" (PDF). FRM Education.

- "Cabinet of South Sudan". Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Education in South Sudan. |