Cognitive psychology

Cognitive psychology is the scientific study of mental processes such as "attention, language use, memory, perception, problem solving, creativity, and thinking".[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Psychology |

|---|

|

|

The origin of cognitive psychology occurred in the 1960s in a break from behaviorism, which had held from the 1920s to 1950s that unobservable mental processes were outside of the realm of empirical science. This break came as researchers in linguistics and cybernetics as well as applied psychology used models of mental processing to explain human behavior. Such research became possible due to the advances in technology that allowed for the measurement of brain activity.

Much of the work derived from cognitive psychology has been integrated into other branches of psychology and various other modern disciplines such as cognitive science, linguistics, and economics.

The domain of cognitive psychology overlaps with that of cognitive science, which takes a more interdisciplinary approach and includes studies of non-human subjects and artificial intelligence.

History

Philosophically, ruminations of the human mind and its processes have been around since the times of the ancient Greeks. In 387 BCE, Plato is known to have suggested that the brain was the seat of the mental processes.[2] In 1637, René Descartes posited that humans are born with innate ideas, and forwarded the idea of mind-body dualism, which would come to be known as substance dualism (essentially the idea that the mind and the body are two separate substances).[3] From that time, major debates ensued through the 19th century regarding whether human thought was solely experiential (empiricism), or included innate knowledge (rationalism). Some of those involved in this debate included George Berkeley and John Locke on the side of empiricism, and Immanuel Kant on the side of nativism.[4]

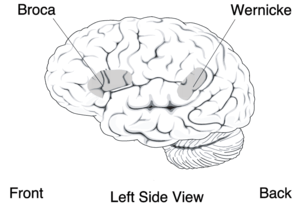

With the philosophical debate continuing, the mid to late 19th century was a critical time in the development of psychology as a scientific discipline. Two discoveries that would later play substantial roles in cognitive psychology were Paul Broca's discovery of the area of the brain largely responsible for language production,[3] and Carl Wernicke's discovery of an area thought to be mostly responsible for comprehension of language.[5] Both areas were subsequently formally named for their founders and disruptions of an individual's language production or comprehension due to trauma or malformation in these areas have come to commonly be known as Broca's aphasia and Wernicke's aphasia.

From the 1920s to the 1950s, the main approach to psychology was behaviorism. Initially, its adherents viewed mental events such as thoughts, ideas, attention, and consciousness as unobservables, hence outside the realm of a science of psychology. One pioneer of cognitive psychology, who worked outside the boundaries (both intellectual and geographical) of behaviorism was Jean Piaget. From 1926 to the 1950s and into the 1980s, he studied the thoughts, language, and intelligence of children and adults.[6]

In the mid-20th century, three main influences arose that would inspire and shape cognitive psychology as a formal school of thought:

- With the development of new warfare technology during WWII, the need for a greater understanding of human performance came to prominence. Problems such as how to best train soldiers to use new technology and how to deal with matters of attention while under duress became areas of need for military personnel. Behaviorism provided little if any insight into these matters and it was the work of Donald Broadbent, integrating concepts from human performance research and the recently developed information theory, that forged the way in this area.[4]

- Developments in computer science would lead to parallels being drawn between human thought and the computational functionality of computers, opening entirely new areas of psychological thought. Allen Newell and Herbert Simon spent years developing the concept of artificial intelligence (AI) and later worked with cognitive psychologists regarding the implications of AI. This encouraged a conceptualization of mental functions patterned on the way that computers handled such things as memory storage and retrieval,[4] and it opened an important doorway for cognitivism.

- Noam Chomsky's 1959 critique[7] of behaviorism, and empiricism more generally, initiated what would come to be known as the "cognitive revolution". Inside psychology, in criticism of behaviorism, J. S. Bruner, J. J. Goodnow & G. A. Austin wrote "a study of thinking" in 1956. In 1960, G. A. Miller, E. Galanter and K. Pribram wrote their famous "Plans and the Structure of Behavior". The same year, Bruner and Miller founded the Harvard Center for Cognitive Studies, which institutionalized the revolution and launched the field of cognitive science.

- Formal recognition of the field involved the establishment of research institutions such as George Mandler's Center for Human Information Processing in 1964. Mandler described the origins of cognitive psychology in a 2002 article in the Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences[8]

Ulric Neisser put the term "cognitive psychology" into common use through his book Cognitive Psychology, published in 1967.[9] Neisser's definition of "cognition" illustrates the then-progressive concept of cognitive processes:

The term "cognition" refers to all processes by which the sensory input is transformed, reduced, elaborated, stored, recovered, and used. It is concerned with these processes even when they operate in the absence of relevant stimulation, as in images and hallucinations. ... Given such a sweeping definition, it is apparent that cognition is involved in everything a human being might possibly do; that every psychological phenomenon is a cognitive phenomenon. But although cognitive psychology is concerned with all human activity rather than some fraction of it, the concern is from a particular point of view. Other viewpoints are equally legitimate and necessary. Dynamic psychology, which begins with motives rather than with sensory input, is a case in point. Instead of asking how a man's actions and experiences result from what he saw, remembered, or believed, the dynamic psychologist asks how they follow from the subject's goals, needs, or instincts.[9]

Cognitive processes

The main focus of cognitive psychologists is on the mental processes that affect behavior. Those processes include, but are not limited to, the following three stages of memory:

1-sensory memory storage: holds sensory information

2-short term memory storage: holds information temporarily for analysis and retrieves information from the Long term memory.

3- Long term memory: holds information over an extended period of time which receives information from the short term memory.

Attention

The psychological definition of attention is "a state of focused awareness on a subset of the available perceptual information".[10] A key function of attention is to identify irrelevant data and filter it out, enabling significant data to be distributed to the other mental processes.[4] For example, the human brain may simultaneously receive auditory, visual, olfactory, taste, and tactile information. The brain is able to consciously handle only a small subset of this information, and this is accomplished through the attentional processes.[4]

Attention can be divided into two major attentional systems: exogenous control and endogenous control.[11] Exogenous control works in a bottom-up manner and is responsible for orienting reflex, and pop-out effects.[11] Endogenous control works top-down and is the more deliberate attentional system, responsible for divided attention and conscious processing.[11]

One major focal point relating to attention within the field of cognitive psychology is the concept of divided attention. A number of early studies dealt with the ability of a person wearing headphones to discern meaningful conversation when presented with different messages into each ear; this is known as the dichotic listening task.[4] Key findings involved an increased understanding of the mind's ability to both focus on one message, while still being somewhat aware of information being taken in from the ear not being consciously attended to. E.g., participants (wearing earphones) may be told that they will be hearing separate messages in each ear and that they are expected to attend only to information related to basketball. When the experiment starts, the message about basketball will be presented to the left ear and non-relevant information will be presented to the right ear. At some point the message related to basketball will switch to the right ear and the non-relevant information to the left ear. When this happens, the listener is usually able to repeat the entire message at the end, having attended to the left or right ear only when it was appropriate.[4] The ability to attend to one conversation in the face of many is known as the cocktail party effect.

Other major findings include that participants can't comprehend both passages when shadowing one passage, they can't report the content of the unattended message, they can shadow a message better if the pitches in each ear are different.[12] However, while deep processing doesn't occur, early sensory processing does. Subjects did notice if the pitch of the unattended message changed or if it ceased altogether, and some even oriented to the unattended message if their name was mentioned.[12]

Memory

The two main types of memory are short-term memory and long-term memory; however, short-term memory has become better understood to be working memory. Cognitive psychologists often study memory in terms of working memory.

Working memory

Though working memory is often thought of as just short-term memory, it is more clearly defined as the ability to process and maintain temporary information in a wide range of everyday activities in the face of distraction. The famously known capacity of memory of 7 plus or minus 2 is a combination of both memories in working memory and long term memory.

One of the classic experiments is by Ebbinghaus, who found the serial position effect where information from the beginning and end of the list of random words were better recalled than those in the center.[13] This primacy and recency effect varies in intensity based on list length.[13] Its typical U-shaped curve can be disrupted by an attention-grabbing word; this is known as the Von Restorff effect.

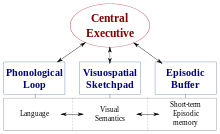

Many models of working memory have been made. One of the most regarded is the Baddeley and Hitch model of working memory. It takes into account both visual and auditory stimuli, long-term memory to use as a reference, and a central processor to combine and understand it all.

A large part of memory is forgetting, and there is a large debate among psychologists of decay theory versus interference theory.

Long-term memory

Modern conceptions of memory are usually about long-term memory and break it down into three main sub-classes. These three classes are somewhat hierarchical in nature, in terms of the level of conscious thought related to their use.[14]

- Procedural memory is memory for the performance of particular types of action. It is often activated on a subconscious level, or at most requires a minimal amount of conscious effort.[15] Procedural memory includes stimulus-response-type information, which is activated through association with particular tasks, routines, etc. A person is using procedural knowledge when they seemingly "automatically" respond in a particular manner to a particular situation or process.[14] An example is driving a car.

- Semantic memory is the encyclopedic knowledge that a person possesses. Knowledge like what the Eiffel Tower looks like, or the name of a friend from sixth grade, represent semantic memory. Access of semantic memory ranges from slightly to extremely effortful, depending on a number of variables including but not limited to recency of encoding of the information, number of associations it has to other information, frequency of access, and levels of meaning (how deeply it was processed when it was encoded).[14]

- Episodic memory is the memory of autobiographical events that can be explicitly stated. It contains all memories that are temporal in nature, such as when one last brushed one's teeth or where one was when one heard about a major news event. Episodic memory typically requires the deepest level of conscious thought, as it often pulls together semantic memory and temporal information to formulate the entire memory.[14]

Perception

Perception involves both the physical senses (sight, smell, hearing, taste, touch, and proprioception) as well as the cognitive processes involved in interpreting those senses. Essentially, it is how people come to understand the world around them through the interpretation of stimuli.[16] Early psychologists like Edward B. Titchener began to work with perception in their structuralist approach to psychology. Structuralism dealt heavily with trying to reduce human thought (or "consciousness," as Titchener would have called it) into its most basic elements by gaining an understanding of how an individual perceives particular stimuli.[17]

Current perspectives on perception within cognitive psychology tend to focus on particular ways in which the human mind interprets stimuli from the senses and how these interpretations affect behavior. An example of the way in which modern psychologists approach the study of perception is the research being done at the Center for Ecological Study of Perception and Action at the University of Connecticut (CESPA). One study at CESPA concerns ways in which individuals perceive their physical environment and how that influences their navigation through that environment.[18]

Language

Psychologists have had an interest in the cognitive processes involved with language that dates back to the 1870s, when Carl Wernicke proposed a model for the mental processing of language.[19] Current work on language within the field of cognitive psychology varies widely. Cognitive psychologists may study language acquisition,[20] individual components of language formation (like phonemes),[21] how language use is involved in mood, or numerous other related areas.

Significant work has been done recently with regard to understanding the timing of language acquisition and how it can be used to determine if a child has, or is at risk of, developing a learning disability. A study from 2012, showed that while this can be an effective strategy, it is important that those making evaluations include all relevant information when making their assessments. Factors such as individual variability, socioeconomic status, short-term and long-term memory capacity, and others must be included in order to make valid assessments.[20]

Metacognition

Metacognition, in a broad sense, is the thoughts that a person has about their own thoughts. More specifically, metacognition includes things like:

- How effective a person is at monitoring their own performance on a given task (self-regulation).

- A person's understanding of their capabilities on particular mental tasks.

- The ability to apply cognitive strategies.[22]

Much of the current study regarding metacognition within the field of cognitive psychology deals with its application within the area of education. Being able to increase a student's metacognitive abilities has been shown to have a significant impact on their learning and study habits.[23] One key aspect of this concept is the improvement of students' ability to set goals and self-regulate effectively to meet those goals. As a part of this process, it is also important to ensure that students are realistically evaluating their personal degree of knowledge and setting realistic goals (another metacognitive task).[24]

Common phenomena related to metacognition include:

- Déjà Vu: feeling of a repeated experience

- Cryptomnesia: generating thought believing it is unique but it is actually a memory of a past experience, aka unconscious plagiarism.

- False Fame Effect: non-famous names can be made to be famous

- Validity effect: statements seem more valid upon repeated exposure

- Imagination inflation: imagining an event that did not occur and having increased confidence that it did occur

Modern perspectives

Modern perspectives on cognitive psychology generally address cognition as a dual process theory, expounded upon by Daniel Kahneman in 2011.[25] Kahneman differentiated the two styles of processing more, calling them intuition and reasoning. Intuition (or system 1), similar to associative reasoning, was determined to be fast and automatic, usually with strong emotional bonds included in the reasoning process. Kahneman said that this kind of reasoning was based on formed habits and very difficult to change or manipulate. Reasoning (or system 2) was slower and much more volatile, being subject to conscious judgments and attitudes.[25]

Applications

Abnormal psychology

Following the cognitive revolution, and as a result of many of the principal discoveries to come out of the field of cognitive psychology, the discipline of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) evolved. Aaron T. Beck is generally regarded as the father of cognitive therapy, a particular type of CBT treatment.[26] His work in the areas of recognition and treatment of depression has gained worldwide recognition. In his 1987 book titled Cognitive Therapy of Depression, Beck puts forth three salient points with regard to his reasoning for the treatment of depression by means of therapy or therapy and antidepressants versus using a pharmacological-only approach:

1. Despite the prevalent use of antidepressants, the fact remains that not all patients respond to them. Beck cites (in 1987) that only 60 to 65% of patients respond to antidepressants, and recent meta-analyses (a statistical breakdown of multiple studies) show very similar numbers.[27]

2. Many of those who do respond to antidepressants end up not taking their medications, for various reasons. They may develop side-effects or have some form of personal objection to taking the drugs.

3. Beck posits that the use of psychotropic drugs may lead to an eventual breakdown in the individual's coping mechanisms. His theory is that the person essentially becomes reliant on the medication as a means of improving mood and fails to practice those coping techniques typically practiced by healthy individuals to alleviate the effects of depressive symptoms. By failing to do so, once the patient is weaned off of the antidepressants, they often are unable to cope with normal levels of depressed mood and feel driven to reinstate use of the antidepressants.[28]

Social psychology

Many facets of modern social psychology have roots in research done within the field of cognitive psychology.[29] Social cognition is a specific sub-set of social psychology that concentrates on processes that have been of particular focus within cognitive psychology, specifically applied to human interactions. Gordon B. Moskowitz defines social cognition as "... the study of the mental processes involved in perceiving, attending to, remembering, thinking about, and making sense of the people in our social world".[30]

The development of multiple social information processing (SIP) models has been influential in studies involving aggressive and anti-social behavior. Kenneth Dodge's SIP model is one of, if not the most, empirically supported models relating to aggression. Among his research, Dodge posits that children who possess a greater ability to process social information more often display higher levels of socially acceptable behavior. His model asserts that there are five steps that an individual proceeds through when evaluating interactions with other individuals and that how the person interprets cues is key to their reactionary process.[31]

Developmental psychology

Many of the prominent names in the field of developmental psychology base their understanding of development on cognitive models. One of the major paradigms of developmental psychology, the Theory of Mind (ToM), deals specifically with the ability of an individual to effectively understand and attribute cognition to those around them. This concept typically becomes fully apparent in children between the ages of 4 and 6. Essentially, before the child develops ToM, they are unable to understand that those around them can have different thoughts, ideas, or feelings than themselves. The development of ToM is a matter of metacognition, or thinking about one's thoughts. The child must be able to recognize that they have their own thoughts and in turn, that others possess thoughts of their own.[32]

One of the foremost minds with regard to developmental psychology, Jean Piaget, focused much of his attention on cognitive development from birth through adulthood. Though there have been considerable challenges to parts of his stages of cognitive development, they remain a staple in the realm of education. Piaget's concepts and ideas predated the cognitive revolution but inspired a wealth of research in the field of cognitive psychology and many of his principles have been blended with modern theory to synthesize the predominant views of today.[33]

Educational psychology

Modern theories of education have applied many concepts that are focal points of cognitive psychology. Some of the most prominent concepts include:

- Metacognition: Metacognition is a broad concept encompassing all manners of one's thoughts and knowledge about their own thinking. A key area of educational focus in this realm is related to self-monitoring, which relates highly to how well students are able to evaluate their personal knowledge and apply strategies to improve knowledge in areas in which they are lacking.[34]

- Declarative knowledge and procedural knowledge: Declarative knowledge is a persons 'encyclopedic' knowledge base, whereas procedural knowledge is specific knowledge relating to performing particular tasks. The application of these cognitive paradigms to education attempts to augment a student's ability to integrate declarative knowledge into newly learned procedures in an effort to facilitate accelerated learning.[34]

- Knowledge organization: Applications of cognitive psychology's understanding of how knowledge is organized in the brain has been a major focus within the field of education in recent years. The hierarchical method of organizing information and how that maps well onto the brain's memory are concepts that have proven extremely beneficial in classrooms.[34]

Personality psychology

Cognitive therapeutic approaches have received considerable attention in the treatment of personality disorders in recent years. The approach focuses on the formation of what it believes to be faulty schemata, centralized on judgmental biases and general cognitive errors.[35]

Cognitive psychology vs. cognitive science

The line between cognitive psychology and cognitive science can be blurry. Cognitive psychology is better understood as predominantly concerned with applied psychology and the understanding of psychological phenomena. Cognitive psychologists are often heavily involved in running psychological experiments involving human participants, with the goal of gathering information related to how the human mind takes in, processes, and acts upon inputs received from the outside world.[36] The information gained in this area is then often used in the applied field of clinical psychology.

Cognitive science is better understood as predominantly concerned with a much broader scope, with links to philosophy, linguistics, anthropology, neuroscience, and particularly with artificial intelligence. It could be said that cognitive science provides the corpus of information feeding the theories used by cognitive psychologists.[37] Cognitive scientists' research sometimes involves non-human subjects, allowing them to delve into areas which would come under ethical scrutiny if performed on human participants. I.e., they may do research implanting devices in the brains of rats to track the firing of neurons while the rat performs a particular task. Cognitive science is highly involved in the area of artificial intelligence and its application to the understanding of mental processes.

Criticisms

Lack of cohesion

Some observers have suggested that as cognitive psychology became a movement during the 1970s, the intricacies of the phenomena and processes it examined meant it also began to lose cohesion as a field of study. In Psychology: Pythagoras to Present, for example, John Malone writes: "Examinations of late twentieth-century textbooks dealing with "cognitive psychology", "human cognition", "cognitive science" and the like quickly reveal that there are many, many varieties of cognitive psychology and very little agreement about exactly what may be its domain."[3] This misfortune produced competing models that questioned information-processing approaches to cognitive functioning such as Decision Making and Behavioral Science.

Lack of empirical support

In the early years of cognitive psychology, behaviorist critics held that the empiricism it pursued was incompatible with the concept of internal mental states; but cognitive neuroscience continues to gather evidence of direct correlations between physiological brain activity and putative mental states, endorsing the basis for cognitive psychology.[38]

There is however disagreement between neuropsychologists and cognitive psychologists. Cognitive psychology has produced models of cognition which are not supported by modern brain science. It is often the case that the advocates of different cognitive models form a dialectic relationship with one another thus affecting empirical research, with researchers siding with their favourite theory. For example, advocates of mental model theory have attempted to find evidence that deductive reasoning is based on image thinking, while the advocates of mental logic theory have tried to prove that it is based on verbal thinking, leading to a disorderly picture of the findings from brain imaging and brain lesion studies. When theoretical claims are put aside, the evidence shows that interaction depends on the type of task tested, whether visuospatially or linguistically oriented; but that there is also an aspect of reasoning which is not covered by either theory.[39]

Similarly, neurolinguists have found that it is easier to make sense of brain imaging studies when the theories are left aside.[40][41] In the field of language cognition research, generative grammar has taken the position that language resides within its private cognitive module, while 'Cognitive Linguistics' goes to the opposite extreme by claiming that language is not an independent function, but operates on general cognitive capacities such as visual processing and motor skills. Consensus in neuropsychology however takes the middle position that, while language is a specialised function, it overlaps or interacts with visual processing.[39][42] Nonetheless, much of the research in language cognition continues to be divided along the lines of generative grammar and Cognitive Linguistics; and this, again, affects adjacent research fields including language development and language acquisition.[43]

Major research areas

- Induction and acquisition

- Judgement and classification

- Representation and structure

- Similarity

Knowledge representation

- Dual-coding theories

- Media psychology

- Mental imagery

- Numerical cognition

- Propositional encoding

- Language acquisition

- Language processing

- Aging and memory

- Autobiographical memory

- Childhood memory

- Constructive memory

- Emotion and memory

- Episodic memory

- Eyewitness memory

- False memories

- Flashbulb memory

- List of memory biases

- Long-term memory

- Semantic memory

- Short-term memory

- Source-monitoring error

- Spaced repetition

- Working memory

- Attention

- Object recognition

- Pattern recognition

- Perception

- Psychophysics

- Time sensation

- Choice (Glasser's theory)

- Concept formation

- Decision making

- Logic

- Psychology of reasoning

- Problem solving

Influential cognitive psychologists

- John R. Anderson

- Alan Baddeley

- David Ausubel

- Albert Bandura

- Frederic Bartlett

- Elizabeth Bates

- Aaron T. Beck

- Robert Bjork

- Gordon H. Bower

- Donald Broadbent

- Jerome Bruner

- Susan Carey

- Noam Chomsky

- Fergus Craik

- Antonio Damasio

- Hermann Ebbinghaus

- Albert Ellis

- William Estes

- Eugene Galanter

- Vittorio Gallese

- Michael Gazzaniga

- Dedre Gentner

- Vittorio Guidano

- Philip Johnson-Laird

- Daniel Kahneman

- Nancy Kanwisher

- Eric Lenneberg

- Alan Leslie

- Willem Levelt

- Elizabeth Loftus

- Alexander Luria

- Brian MacWhinney

- George Mandler

- Jean Matter Mandler

- Ellen Markman

- James McClelland

- George Armitage Miller

- Ulrich Neisser

- Allen Newell

- Allan Paivio

- Seymour Papert

- Jean Piaget

- Steven Pinker

- Michael Posner

- Karl H. Pribram

- Giacomo Rizzolatti

- Henry L. Roediger III

- Eleanor Rosch

- David Rumelhart

- Eleanor Saffran

- Daniel Schacter

- Otto Selz

- Roger Shepard

- Richard Shiffrin

- Herbert A. Simon

- George Sperling

- Robert Sternberg

- Larry Squire

- Saul Sternberg

- Anne Treisman

- Endel Tulving

- Amos Tversky

- Lev Vygotsky

See also

References

- "American Psychological Association (2013). Glossary of psychological terms". Apa.org. Retrieved 2014-08-13.

- "Mangels, J. History of neuroscience". Columbia.edu. Retrieved 2014-08-13.

- Malone, J.C. (2009). Psychology: Pythagoras to Present. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. (a pp. 143, b pp. 293, c pp. 491)

- Anderson, J.R. (2010). Cognitive Psychology and Its Implications. New York, NY: Worth Publishers.

- Eysenck, M.W. (1990). Cognitive Psychology: An International Review. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. (pp. 111)

- Smith, L. (2000). About Piaget. Retrieved from http://piaget.org/aboutPiaget.html

- Chomsky, N. A. (1959), A Review of Skinner's Verbal Behavior

- Mandler, G. (2002). Origins of the cognitive (r)evolution. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 38, 339–353.

- Neisser, U. (1967). Cognitive Psychology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Neisser's definition on page 4.

- "How does the APA define "psychology"?". Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- Chica, Ana B.; Bartolomeo, Paolo; Lupiáñez, Juan (2013). "Two cognitive and neural systems for endogenous and exogenous spatial attention". Behavioural Brain Research. 237: 107–123. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2012.09.027. PMID 23000534.

- Cherry, E. Colin (1953). "Some Experiments on the Recognition of Speech, with One and with Two Ears". The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 25 (5): 975–979. doi:10.1121/1.1907229. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-002A-F750-3.

- Ebbinghaus, Hermann (1913). On memory: A contribution to experimental psychology. New York: Teachers College.

- Balota, D.A. & Marsh, E.J. (2004). Cognitive Psychology: Key Readings. New York, NY: Psychology Press. (pp. 364–365)

- "Procedural Memory: Definition and Examples". Live Science. Retrieved 2018-09-06.

- Cherry, K. (2013). Perception and the perceptual process

- "Plucker, J. (2012). Edward Bradford Titchener". Indiana.edu. 2013-11-14. Archived from the original on 2014-07-17. Retrieved 2014-08-13.

- "University of Connecticut (N.D.). Center for the ecological study of perception". Ione.psy.uconn.edu. 2012-11-30. Archived from the original on 1997-04-12. Retrieved 2014-08-13.

- Temple, Christine M. (1990). "Developments and applications of cognitive neuropsychology." In M. W. Eysenck (Ed.)Cognitive Psychology: An International Review. West Sussex, England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. p. 110

- Conti-Ramsden, Gina; Durkin, Kevin (2012). "Language Development and Assessment in the Preschool Period". Neuropsychology Review. 22 (4): 384–401. doi:10.1007/s11065-012-9208-z. PMID 22707315.

- Välimaa-Blum, Riitta (2009). "The phoneme in cognitive phonology: Episodic memories of both meaningful and meaningless units?". Cognitextes (2). doi:10.4000/cognitextes.211.

- Martinez, M. E. (2006). "What is metacognition". The Phi Delta Kappan. 87 (9): 696–699. doi:10.1177/003172170608700916. JSTOR 20442131.

- "Cohen, A. (2010). The secret to learning more while studying". Blog.brainscape.com. Retrieved 2014-08-13.

- "Lovett, M. (2008). Teaching metacognition". Serc.carleton.edu. Retrieved 2014-08-13.

- Kahneman D. (2003) "A perspective on judgement and choice." American Psychologist. 58, 697–720.

- "University of Pennsylvania (N.D). Aaron T. Beck, M.D". Med.upenn.edu. 2013-10-23. Archived from the original on 2017-09-14. Retrieved 2014-08-13.

- Grohol, John M. (2009-02-03). "Grohol, J. (2009). Efficacy of Antidepressants". Psychcentral.com. Retrieved 2014-08-13.

- Beck, A.T. (1987). Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York, NY: Guilford Press

- Cartwright, Dorwin (March 1979). "Contemporary Social Psychology in Historical Perspective". Social Psychology Quarterly. 42 (1): 82–93. doi:10.2307/3033880. ISSN 0190-2725. JSTOR 3033880.

- Moskowitz, G.B. (2004). Social Cognition: Understanding Self and Others. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. (pp. 3)

- Fontaine, R.G. (2012). The Mind of the Criminal: The Role of Developmental Social Cognition in Criminal Defense Law. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. (p. 41)

- "Astington, J.W. & Edward, M.J. (2010). The development of theory of mind in early childhood. Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development, 2010:1–6" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-08-13.

- Brainerd, C.J. (1996). "Piaget: A centennial celebration." Psychological Science, 7(4), 191–194.

- Reif, F. (2008). Applying Cognitive Science to Education: Thinking and Learning in Scientific and Other Complex Domains. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. (a pp. 283–84, b pp. 38)

- Beck, A.T., Freeman, A., & Davis, D.D. (2004). Cognitive Therapy of Personality Disorders (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. (pp. 300).

- Baddeley, A. & Bernses, O.A. (1989). Cognitive Psychology: Research Directions In Cognitive Science: European Perspectives, Vol 1 (pp. 7). East Sussex, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Ltd. (pg. 7)

- "Thagard, P. (2010). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy". Plato.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2014-08-13.

- Gardner, Howard (2006). Changing Minds. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business School Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4221-0329-6.

- Goel, Vinod (2007). "Anatomy of deductive reasoning". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 11 (10): 435–441. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2007.09.003. Retrieved 2020-07-06.

- Kluender, R.; Kutas, M. (1993). "Subjacency as a processing phenomenon" (PDF). Language and Cognitive Processes. 8 (4): 573–633. doi:10.1080/01690969308407588. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- Barkley, C.; Kluender, R.; Kutas, M. (2015). "Referential processing in the human brain: An Event-Related Potential (ERP) study" (PDF). Brain Research. 1629: 143–159. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2015.09.017. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- Schwarz-Friesel, Monika (2012). "On the status of external evidence in the theories of cognitive linguistics". Language Sciences. 34 (6): 656–664. doi:10.1016/j.langsci.2012.04.007.

- Shatz, Marilyn (2007). "On the development of the field of language development". In Hoff and Schatz (ed.). Blackwell Handbook of Language Development. Wiley. pp. 1–15. ISBN 9780470757833.

Further reading

- Groeger, John A. (2002). "Trafficking in cognition: Applying cognitive psychology to driving". Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour. 5 (4): 235–248. doi:10.1016/S1369-8478(03)00006-8.

- Jacobs, A.M. (2001). "Literacy, Cognitive Psychology of". International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences. pp. 8971–8975. doi:10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/01556-4. ISBN 9780080430768.

- Mansell, Warren (2004). "Cognitive psychology and anxiety". Psychiatry. 3 (4): 6–10. doi:10.1383/psyt.3.4.6.32905. S2CID 27321969.

- Philip Quinlan, Philip T. Quinlan, Ben Dyson. 2008. Cognitive Psychology. Publisher-Pearson/Prentice Hall. ISBN 0131298100, 9780131298101

- Robert J. Sternberg, Jeff Mio, Jeffery Scott Mio. 2009. Publisher-Cengage Learning. ISBN 049550629X, 9780495506294

- Nick Braisby, Angus Gellatly. 2012. Cognitive Psychology. Publisher-Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199236992, 9780199236992

External links

| Library resources about Cognitive psychology |

- Cognitive psychology article in Scholarpedia

- Laboratory for Rational Decision Making

- Winston Sieck, 2013. What is Cognition and What Good is it?

- Terry Winograd. 1972. Understanding Natural Language

- Nachshon Meiran, Ziv Chorev, Ayelet Sapir. 2000. Component Processes in Task Switching