Education in Madagascar

Education in Madagascar has a long and distinguished history. Formal schooling began with medieval Arab seafarers, who established a handful of Islamic primary schools (kuttabs) and developed a transcription of the Malagasy language using Arabic script, known as sorabe. These schools were short-lived, and formal education was only to return under the 19th-century Kingdom of Madagascar when the support of successive kings and queens produced the most developed public school system in precolonial Sub-Saharan Africa. However, formal schools were largely limited to the central highlands around the capital of Antananarivo and were frequented by children of the noble class andriana. Among other segments of the island's population, traditional education predominated through the early 20th century. This informal transmission of communal knowledge, skills and norms was oriented toward preparing children to take their place in a social hierarchy dominated by community elders and particularly the ancestors (razana), who were believed to oversee and influence events on earth. . Since coming under French colonial authority in 1896, the education system in Madagascar has steadily expanded into more remote and rural communities while coming under increased control of the state. National education objectives have reflected changing government priorities over time. Colonial schooling taught basic skills and French language fluency to most children, while particularly strong students were selected to receive training for civil servant roles at the secondary level... Post-independence education in the First Republic (1960–1975) under President Philibert Tsiranana retained a strong French influence with textbooks and teachers of French origin. The post-colonial backlash that brought about the Second Republic (1975–1992) saw schools serve as vehicles for citizen indoctrination into Admiral Didier Ratsiraka's socialist ideology. The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 prompted a wave of democratization across Africa, launching the democratic Third Republic (1992–2010). Renewed international cooperation resulted in significant foreign aid for the education sector, which adopted numerous reforms promoted by United Nations organizations and other partners in the international development sector.

_Madagascar.jpg)

Education was prioritized under President Marc Ravalomanana (2001–2009), who sought to improve both access and quality of formal and non-formal education. A massive campaign of school renovation, expansion and construction has been coupled with the recruitment and training of tens of thousands more teachers. This initiative was supported with funds from intergovernmental organizations such as the World Bank and UNESCO, and bilateral grants from many countries, including France, the United States and Japan. A key pedagogical objective of these reforms included a shift from a traditional, didactic teaching style to a student-centered form of instruction involving frequent group work. As of 2009, Madagascar was on target to achieve the Education For All objective of universal enrollment at the primary level. Student achievement, teacher quality, widespread shortage of materials and access to secondary and tertiary schooling continue to be challenges, as are poverty-related obstacles such as high repetition and attrition rates and poor student health. The 2009 political crisis in Madagascar resulted in cessation of all but emergency aid to the country, further exacerbating poverty-related challenges and threatening to undo much recent progress in the education sector.

History of education in Madagascar

Before 1820

Traditionally, education in Madagascar was an informal affair consisting of the transmission of the social norms, practices and knowledge developed and handed down within the community over generations. The hierarchical structure of most traditional Malagasy communities placed elders, parents and other persons of esteem over younger or less distinguished members of the group, and over whom the ancestors (razana) exercised the greatest authority of all. In the context of such a stratified society, traditional education underscored the importance of maintaining one's proper place, trained people in the proper observance of ritual and innumerable fady (taboos) and, above all, taught respect for ancestors.[1]

(Children) learn to respect elders and the ray aman-dreny (authority figures) and to conform to their opinions, speak the appropriate words, follow the rules of traditional wisdom and fear the castigation they can expect in response to their antisocial actions.

— H. Raharijaona, Le droit de la famille à Madagasikara[2]

Learning one's place in traditional Malagasy society extended beyond the youth-adult-elder-ancestor hierarchy. Among many Malagasy ethnic groups, individuals were identified with particular castes; in traditional Merina society, for example, one of the three main castes had seven sub-castes. These divisions were overlaid by such additional factors as gender roles, with consequences for informal education: boys were expected to behave as befits one who would eventually become a ray aman-dreny, while girls were expected to demonstrate mastery of domestic skills and cultivate the qualities of a good wife and mother.[2]

The earliest formal schooling on Madagascar was introduced by Arab seafarers, whose influence on coastal communities extends at least as far back as the 11th century. These travelers attempted to propagate Islam by establishing a limited number of kuttab (Quranic schools that taught literacy and basic numeracy) and transcribed the Malagasy language using the Arabic alphabet in a script termed sorabe. These schools did not persist, and sorabe literacy passed into the realm of arcane knowledge reserved for astrologers, kings and other privileged elites.[3]

1820–1896

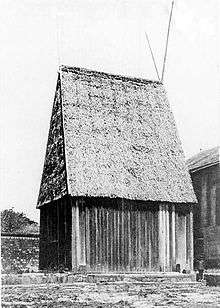

The first formal European-style school was established in 1818 on the east coast of Madagascar at Toamasina by members of the London Missionary Society (LMS). King Radama I (1810–1828), the first sovereign to bring about half the island of Madagascar under his rule, was interested in strengthening ties with European powers; to this end, he invited LMS missionaries to open a school in his capital at Antananarivo within the Rova palace compound to instruct the royal family in literacy, numeracy and basic education. This first school, known as the Palace School, was established by LMS missionary David Jones on December 8, 1820, within the Besakana, a building of great historic and cultural significance. Within months, due to the rapid increase in the number interested in studying there, classes were transferred to a larger, purpose-built structure on the Rova grounds.[4] By 1822, LMS missionaries had successfully transcribed the Merina dialect of the Malagasy language using the Latin alphabet. This dialect, spoken in the central highlands around Antananarivo, was declared the official version of the Malagasy language that year — a status that the highlands dialect has retained ever since.[5] The Bible, which was incrementally translated into this dialect and printed on a press (a process completed in 1835),[6] was the first book printed in the Malagasy language and became the standard text used to teach literacy, thereby spreading the tenets of Christianity in Imerina.[7]

Convinced that Western schooling was vital to developing Madagascar's political and economic strength, in 1825 Radama declared primary schooling to be compulsory for the andriana (nobles) throughout Imerina. Schools were constructed in larger towns throughout the central highlands and staffed with teachers from the LMS and other missionary organizations. By the end of Radama's reign in 1829, 38 schools were providing basic education to over 4,000 students in addition to the 300 students studying at the Palace School,[5] teaching dual messages of loyalty and obedience to Radama's rule and the fundamentals of Christian theology.[7] These schools also provided Radama with a ready pool of educated conscripts for his military activities; consequently, some andriana families sent slave children to spare their own offspring from the perils of military life, producing an educated minority among the lower classes of Merina society.[8] An additional 600 students received vocational training under Scottish missionary James Cameron. However, Radama's successor and widow, Queen Ranavalona I (1828–1861), grew increasingly wary of foreign influence on the island over the course of her 33-year reign. She forbade the education of slaves in 1834. The following year, all of Radama's schools were ordered closed and their missionary teachers were expelled from the country.[5]

Prime Minister Rainilaiarivony (1864–1895), who married Queens Rasoherina (1863–1868), Ranavalona II (1868–1883) and Ranavalona III (1883–1897) in succession, reopened and dramatically expanded the system of schools beginning in 1864. The policy of mandatory schooling among the andriana was reinstated in 1872; by 1881, schooling was declared compulsory for all Malagasy children regardless of ethnicity or class. Two years later, 1,155 mission schools were providing basic education to 133,695 students, establishing the Malagasy school system as the most developed in precolonial Sub-Saharan Africa.[9]

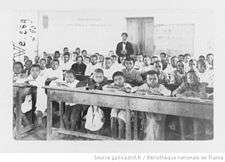

1896–1960

During the colonial period, the French established a system of public schools that was divided into two parts: elite schools, modeled after those of France and reserved for the children of French citizens (a status few Malagasy enjoyed); and indigenous schools for the Malagasy, which offered practical and vocational education but were not designed to train students for positions of leadership or responsibility. Within the first seven years of the colonial period 650 indigenous schools had been established, half of which were dispersed over coastal areas where the schools of the Kingdom of Madagascar had not reached. This initiative expanded the number of students in Madagascar by 50,000, who studied a curriculum focused primarily on French language acquisition and basic knowledge in such areas as hygiene and arithmetic.[10] The long-established mission schools continued to represent a viable education alternative until 1906, when French laws placed stringent restrictions on their operation, forcing thousands of students out of mission schools without adequate capacity to accommodate them within the public system.[11]

Middle-grade Malagasy civil servants and functionaries were trained at the écoles régionales (regional schools), the most important of which was the École le Myre de Villers in Antananarivo. Reforms of the public school system designed to give the Malagasy more education opportunities were initiated after World War II. At independence in 1960, the country had a system of education almost identical to that of France.[1]

Structure

Education is compulsory for children between the ages of six and fourteen. The current education system provides primary schooling for five years, from ages six to eleven. Secondary education lasts for seven years and is divided into two parts: a junior secondary level of four years from ages twelve to fifteen, and a senior secondary level of three years from ages sixteen to eighteen. At the end of the junior level, graduates receive a certificate, and at the end of the senior level, graduates receive the baccalauréat (the equivalent of a high school diploma). A vocational secondary school system, the collège professionelle (professional college), is the equivalent of the junior secondary level; the collège technique (technical college), which awards the baccalauréat technique (technical diploma), is the equivalent of the senior level.[1]

The University of Madagascar, established as an Institute for Advanced Studies in 1955 in Antananarivo and renamed in 1961, is the main institute of higher education. It maintains six separate, independent branches in Antananarivo, Antsiranana, Fianarantsoa, Toamasina, Toliara, and Mahajanga. (Before 1988, the latter five institutions were provincial extensions of the main university in Antananarivo.) The university system consists of several faculties, including law and economics, sciences, and letters and human sciences, and numerous schools that specialize in public administration, management, medicine, social welfare, public works, and agronomy. Official reports have criticized the excessive number of students at the six universities: a total of 40,000 in 1994, whereas the collective capacity is 26,000. Reform measures are underway to improve the success rate of students—only 10 percent complete their programs, and the average number of years required to obtain a given degree is eight to ten compared with five years for African countries. The baccalauréat is required for admission to the university.[1]

Performance

Descriptive statistics

Primary school enrollment is nearly universal, a significant increase from the lower figure of 65 percent enrollment in 1965 (Madagascar had 13,000 public primary schools in 1994); 36 percent of the relevant school-age population attends secondary school (there were 700 general education secondary schools and eighty lycées or classical secondary institutions) and 5 percent of the relevant school-age population attends institutions of higher learning. Despite these statistics, a 1993 UNICEF report considers the education system a "failure," pointing out that in contrast to the early 1980s when education represented approximately 33 percent of the national budget, in 1993 education constituted less than 20 percent of the budget, and 95 percent of this amount was devoted to salaries. The average number of years required for a student to complete primary school was twelve. Girls have equal access with boys to educational institutions.[1]

Outcomes

The gradual expansion of education opportunities has had an impressive impact on Malagasy society, most notably in raising the literacy level of the general population. Only 39 percent of the population could be considered literate in 1966, but the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) estimated that this number had risen to 50 percent at the beginning of the 1980s[1] and to 64 percent in 2010.[12]

Challenges

Access

The national education system often has been at the center of political debate. As is the case throughout Africa, education credentials provide one of the few opportunities to obtain employment in a country with a limited private sector, and the distribution of educational resources has continued to be an issue with explosive political ramifications.

Historically, the system has been characterized by an unequal distribution of education resources among the regions of the country. Because the central highlands had a long history of formal education beginning in the early nineteenth century, this region had more schools and higher educational standards than the coastal regions. The disparity continued to be a major divisive factor in national life in the years following independence. The Merina and the Betsileo peoples, having better access to schools, inevitably tended to be overrepresented in administration and the professions, both under French colonialism and after independence in 1960.

Adding to these geographical inequities is the continued lack of education opportunities for the poorest sectors of society. For example, the riots that led to the fall of the Tsiranana regime in 1972 were initiated by students protesting official education and language policies, including a decision to revoke the newly established competitive examination system that would have allowed access to public secondary schools on the basis of merit rather than the ability to pay. Yet when the Ratsiraka regime attempted in 1978 to correct historical inequalities and make standards for the baccalauréat lower in the disadvantaged provinces outside the capital region, Merina students led riots against what they perceived as an inherently unfair preferential treatment policy.[1]

See also

- Higher education in Madagascar

- Keelonga

References

- Metz, Helen Chapin (1994). "Library of Congress Country Studies: Madagascar (Education)". Archived from the original on February 2, 2011. Retrieved February 1, 2011.

- Raharijaona, H (1968), "Le droit de la famille à Madagasikara", Le droit de la famille en afrique noir et à Madagascar (in French), Paris: UNESCO, pp. 195–220, retrieved February 12, 2011

- Rafaralahy-Bemananjara, Zefaniasy (1983). Enseignement des Langues Maternelles dans les Ecoles Primaires à Madagascar: Division des structures, contenus, méthodes et techniques de l'éducation (PDF) (in French). Paris: UNESCO. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 2, 2011. Retrieved February 1, 2011.

- Ralibera, Daniel (1993), Madagascar et le christianisme (in French), Editions Karthala, p. 196, ISBN 9789290282112, retrieved January 7, 2011

- Koerner, Francis (1999), Histoire de l'Enseignement Privé et Officiel à Madagascar (1820–1995): les Implications Religieuses et Politiques dans la Formation d'un Peuple (in French), Paris: Harmattan, ISBN 978-2-7384-7416-2

- London Missionary Society (1877), "The Bible in Madagascar", The Sunday Magazine, London: Daldy, Isbister & Co, pp. 647–648, retrieved February 12, 2011

- Sharp, Leslie (2002), The Sacrificed Generation: Youth, History, and the Colonized Mind in Madagascar, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-22951-8, retrieved February 2, 2011

- Campbell, Gwyn (1988). "Slavery and fanompoana: The structure of forced labor in Imerina (Madagascar), 1790–1861". The Journal of African History. 29 (3): 463–486. doi:10.1017/s0021853700030589.

- Direction de l'enseignement (1931), L'Enseignement à Madagascar en 1931 (in French), Paris: Government of France

- Gallieni, Joseph-Simon (1908). Neuf ans à Madagascar (in French). Paris: Librairie Hachette. pp. 341–343. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- Goguel, A.M. (2006). Aux Origines du Mai Malgache: Désir d'Ecole et Compétition Sociale, 1951–1972 (in French). Antananarivo: Editions Karthala.

- Madagascar statistics. UNICEF global education statistics database, 2011.