Higher education in the United States

Higher education in the United States is an optional stage of formal learning following secondary education. Higher education, is also referred as post-secondary education, third-stage, third-level, or tertiary education. It covers stages 5 to 8 on the International ISCED 2011 scale. It is delivered at 4,360 Title IV degree-granting institutions, known as colleges or universities.[1] These may be public or private universities, liberal arts colleges, community colleges, or for-profit colleges. US higher education is loosely regulated by several third-party organizations.[2]

| Education in the United States |

|---|

|

|

|

.png)

According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) and National Student Clearinghouse, college enrollment has declined since a peak in 2010–2011 and is projected to continue declining or be stagnant for the next two decades. The US is unique in its investment in highly competitive NCAA sports, particularly in American football and basketball, with large sports stadiums and arenas.[3]

History

Colonial era to 19th century

.jpg)

_seen_from_the_southeast_with_the_Italian_Pavilion_in_the_foreground.jpg)

Religious denominations established early colleges in order to train ministers. Harvard College was founded by the colonial legislature in 1636. According to historian John Thelin, most instructors were lowly paid 'tutors'.[4] In Ebony and Ivy, Craig Steven Wilder documented the history of early higher education in the US, including the oppression of indigenous people and enslaved Africans at elite colleges.[5]

Protestants and Catholics opened over hundreds of small denominational colleges in the 19th century. In 1899 they enrolled 46 percent of all U.S. undergraduates. Many closed or merged but in 1905 there were over 500 in operation.[6][7] Catholics opened several women's colleges in the early 20th century. Schools were small, with a limited undergraduate curriculum based on the liberal arts. Students were drilled in Greek, Latin, geometry, ancient history, logic, ethics and rhetoric, with few discussions and no lab sessions. Originality and creativity were not prized, but exact repetition was rewarded. College presidents typically enforced strict discipline, and upperclassman enjoyed hazing freshman. Many students were younger than 17, and most colleges also operated a preparatory school. There were no organized sports, or Greek-letter fraternities, but literary societies were active. Tuition was low and scholarships were few. Many of their students were sons of clergymen; most planned professional careers as ministers, lawyers or teachers.[8]

The nation's small colleges helped young men make the transition from rural farms to complex urban occupations. These schools promoted upward mobility by preparing ministers and providing towns with a core of community leaders. Elite colleges became increasingly exclusive and contributed little upward social mobility. By concentrating on the offspring of wealthy families, and ministers, elite Eastern colleges such as Harvard, played a role in the formation of a Northeastern elite.[9]

Catholic colleges and universities

The Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities was founded in 1899 and continues to facilitate the exchange of information and methods.[10] Vigorous debate in recent decades has focused on how to balance Catholic and academic roles, with conservatives arguing that bishops should exert more control to guarantee orthodoxy.[11][12][13]

Timeline of key federal legislation

- Morrill Act (1862 and 1890)

- Smith–Hughes Act or National Vocational Education Act (1917)[14]

- Federal Student Aid Program (1934–1943)[15]

- G.I. Bill (1944)

- National Defense Education Act (1958)

- Higher Education Act (1965)

- Education Amendments (1972)

20th century

At the beginning of the 20th century, less than 1,000 colleges with 160,000 students existed in the US. The number of colleges skyrocketed in waves, during the early and mid 20th century. State universities grew from small institutions of fewer than 1,000 students to campuses with 40,000 more students, with networks of regional campuses around the state. In turn, regional campuses broke away and became separate universities.

To handle the explosive growth of K–12 education, every state set up a network of teachers' colleges, beginning with Massachusetts in the 1830s. After 1950, they became state colleges and then state universities with a broad curriculum.

Major new trends included the development of the junior colleges. They were usually set up by city school systems starting in the 1920s.[16] By the 1960s they were renamed as "community colleges."

Junior colleges grew from 20 in number In 1909, to 170 in 1919. By 1922, 37 states had set up 70 junior colleges, enrolling about 150 students each. Meanwhile, another 137 were privately operated, with about 60 students each. Rapid expansion continued in the 1920s, with 440 junior colleges in 1930 enrolling about 70,000 students. The peak year for private institutions came in 1949, when there were 322 junior colleges in all; 180 were affiliated with churches, 108 were independent non-profit, and 34 were private schools run for-profit.[17]

Many factors contributed to rapid growth of community colleges. Students parents and businessmen wanted nearby, low-cost schools to provide training for the growing white-collar labor force, as well as for more advanced technical jobs in the blue-collar sphere. Four-year colleges were also growing, albeit not as fast; however, many of them were located in rural or small-town areas away from the fast-growing metropolis. Community colleges continue as open-enrollment, low-cost institutions with a strong component of vocational education, as well as a low-cost preparation for transfer students into four-year schools. They appeal to a poorer, older, less prepared element.[18][19]

College students were involved in social movements long before the 20th century, but the most dramatic student movements rose in the 1960s. In the 1960s, students organized for civil rights and against the Vietnam War. In the 1970s, students led movements for women's rights and gay rights, as well as protests against South African apartheid.[20]

While for-profit colleges originated during Colonial times, growth in these schools was most apparent from the 1980s to about 2011. For-profit college enrollment, however, has declined significantly since 2011, after several federal investigations. For-profit colleges were criticized for predatory marketing and sales practices.[21] The failures of Corinthian Colleges and ITT Technical Institute were the most remarkable closings.[22] In 2018, the documentary Fail State chronicled the boom and bust of for-profit colleges, highlighting the abuses that led to their downfall.[23]

21st century

Changing technology, mergers and closings, and politics have resulted in dramatic changes in US higher education during the 21st century.

Online education and MOOCs

Online education has grown in the early 21st century. More than 6.3 million students in the U.S. took at least one online course in fall 2016.[24] While online attendance has increased, confidence among chief academic officers has decreased from 70.8 percent in 2015 to 63.3 percent in 2016.[25] In 2017, about 15% of all students attended exclusively online, and competition for online students has been increasing[26]

By 2018, more than one hundred short-term coding bootcamps existed in the US. Programs were available at Harvard University's extension school and the extension schools at Georgia Tech, University of Pennsylvania, Cal Berkeley, Northwestern, UCLA, University of North Carolina, University of Texas, George Washington, Vanderbilt University, and Rutgers through Trilogy Education Services.[27][28]

In 2019, researchers at George Mason University concluded that online education has "contributed to increasing gaps in educational success across socioeconomic groups while failing to improve affordability".[29][30][31]

A MOOC is a massive open online course aimed at unlimited participation and open access via the web. It became popular in 2010–14. In addition to traditional course materials such as filmed lectures, readings, and problem sets, many MOOCs provide interactive user forums to support community interactions between students, professors, and teaching assistants.[32] Robert Zemsky (2014), of the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education notes that they at first seemed to be an extremely inexpensive method of bringing top teachers at low cost directly to students. However, very few students—usually under 5%—were able to finish a MOOC course. He argues that they have passed their peak: "They came; they conquered very little; and now they face substantially diminished prospects."[33] In 2019, researchers at MIT found that MOOCs had completion rates of 3 percent and that the number of people taking these courses has been declining since 2012–13.[34]

Online programs for many universities are often managed by privately owned companies called OPMs. The OPMs include 2U, HotChalk and iDesign. Trace Urdan, managing director at Tyton Partners, "estimates that the market for OPMs and related services will be worth nearly $8 billion by 2020." [35]

Financial difficulties, mergers and downsizing

Hundreds of colleges are expected to close or merge, according to research from Ernst & Young.[36] The US Department of Education publishes a monthly list of campus and learning site closings. Typically there are 300 to 1000 closings per year.[37][38] Notable college closings include for-profit Corinthian Colleges (2015), ITT Technical Institute (2016), Brightwood College and Virginia College(2018).[39][40] Private college closings include Wheelock College (2018) and Green Mountain College (2019).[41]

In December 2017, Moody's credit rating agency downgraded the US higher education outlook from stable to negative, "citing financial strains at both public and private four-year institutions."[42] In June 2018, Moody's released data on declining college enrollments and constraints, noting that tuition pricing would suppress tuition revenue growth.[43]

Other businesses related to higher education have also had financial difficulties. In May 2019, two academic publishers, Cengage and McGraw Hill, merged.[44]

Protests and political clashes

Student protests and clashes between left and right appeared on several US campuses in 2017.[45][46][47][48][49] On August 11, 2017, white nationalists and members of the alt-right rallied at the University of Virginia, protesting the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee.[50] The following day, one person died during protests in Charlottesville.[51] Following this event, speaking engagements by Richard Spencer were canceled at Texas A&M University and the University of Florida.[52]

Functions

US higher education functions as an institution of knowledge but has several secondary functions. According to Marcus Ford, the primary function went through four phases in American history: preserving Christian civilization, advancing the national interest, research, and growing the global economy.[53] It has also served as a source for professional credentials, as a vehicle for social mobility, and as a social sorter.[54][55] The college functions as a 'status marker', "signaling membership in the educated class, and a place to meet spouses of similar status".[56]

In 2018, Universitas 21 (U21), the network of research-intensive universities, ranked the US first globally for overall higher education, but only 15th when GDP was factored into the equation. Accounting for GDP, the top 10 nations for higher education in 2018 were Finland, the United Kingdom, Serbia, Denmark, Sweden, Portugal, Switzerland, South Africa, Israel and New Zealand.[57]

Strong research funding helped 'elite American universities' dominate global rankings in the early 21st century, making them attractive to international students, professors and researchers.[58] Other countries, though, are offering incentives to compete for researchers[59] as funding is threatened in the US[60][61] and US dominance of international tables has lessened.[62][63] The system has also been blighted by fly-by-night schools, diploma mills, visa mills, and predatory for-profit colleges.[64][65][66][67] There have been some attempts to reform the system through federal policy such as gainful employment regulations, particularly through the Department of Education's College Scorecard, which enables students to see the socio-economic diversity, SAT/ACT scores, graduation rates, and average earnings and debt of graduates at all colleges.[68]

According to Pew Research Center and Gallup poll surveys, public opinion about colleges has been declining, especially among Republicans and the white working class.[69][70][71][72] The higher education industry has been criticized for being unnecessarily expensive, providing a difficult-to-measure service which is seen as vital but in which providers are paid for inputs instead of outputs, which is beset with federal regulations that drive up costs, and payments coming from third parties, not users.[73] In a 2018 Pew survey, 61 percent of those polled said that US higher education was headed in the wrong direction.[74] A 2019 Gallup survey found that, among graduates who strongly felt a purpose in life was important, "only 40 percent said they had found a meaningful career after college."[75]

Types of colleges and universities

US colleges and universities offer diverse educational venues: some emphasize a vocational, business, engineering, or technical curriculum (like polytechnic universities and land-grant universities) and others emphasize a liberal arts curriculum. Many combine some or all of the above, as comprehensive universities.

Terminology

The term "college" refers to one of three types of education institutions: stand-alone higher level education institutions that are not components of a university.

- community colleges

- liberal arts colleges

- a college within a university, mostly the undergraduate institution of a university.

Almost all colleges and universities are coeducational. A dramatic transition occurred in the 1970s, when most men's colleges started to accept women. Over 80% of the women's colleges of the 1960s have closed or merged, leaving fewer than 50. Over 100 historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) operate, both private and public.

Some U.S. states offer higher education at two year "colleges" formerly called "community colleges". The change requires cooperation between community colleges and local universities.

Four-year colleges often provide the bachelor's degree, most commonly the Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) or Bachelor of Science (B.S.). They are primarily either undergraduate only institutions (e.g. liberal arts colleges), or the undergraduate institution of a university (such as Harvard College and Yale College).

Higher education has led to the creation of accreditation organizations, independent of the government, to vouch for the quality of degrees. They rate institutions on academic quality, the quality of their libraries, the publishing records of their faculty, the degrees which their faculty hold, and their financial solvency. Accrediting agencies have been criticized for possible conflicts of interest that lead to favorable results.[76] Non-accredited institutions exist, but their students are not eligible for federal loans.

Universities

Universities are educational institutions with undergraduate and graduate programs. For historical reasons, some universities[77] have retained the term college instead of "university" for their name. Graduate programs grant a variety of master's degrees (like the Master of Arts (M.A.), Master of Science (M.S.), Master of Business Administration (M.B.A.) or Master of Fine Arts (M.F.A.) in addition to doctorates such as the Ph.D. The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education distinguishes among institutions on the basis of the prevalence of degrees they grant and considers the granting of master's degrees necessary, although not sufficient, for an institution to be classified as a university.[78]

Some universities have professional schools. Examples include journalism school, business school, medical schools, pharmacy schools (Pharm.D.), and dental schools. A common practice is to refer to these disparate faculties within universities as colleges or schools.

The American university system is largely decentralized. Public universities are administered by the individual states and territories, usually as part of a state university system. Except for the United States service academies and staff colleges, the federal government does not directly regulate universities. However, it can offer federal grants and any institution that receives federal funds must certify that it has adopted and implemented a drug prevention program that meets federal regulations.[79][80]

Each state supports at least one state university and several support several. At one extreme, California has three public higher education systems: the 10-campus University of California, the 23-campus California State University, and the 112-campus California Community Colleges System. In contrast, Wyoming supports a single state university. Public universities often have large student bodies, with introductory classes numbering in the hundreds, with some undergraduate classes taught by graduate students. Tribal colleges operated on Indian reservations by some federally recognized tribes are also public institutions.

Many private universities exist. Some are secular and others are involved in religious education. Some are non-denominational, and some are affiliated with a certain sect or church, such as Roman Catholicism (with different institutions often sponsored by particular religious institutes such as the Jesuits) or religions such as Lutheranism or Mormonism. Seminaries are private institutions for those preparing to become members of the clergy. Most private schools (like all public schools) are non-profit, although some are for-profit.

Community colleges

Community colleges are often two-year colleges. They have open admissions, usually with lower tuition fees than other state or private schools. Graduates earn associate degrees, such as an Associate of Arts (AA). Many students earn an AA at a two-year institution before transferring to a four-year institution to complete studies for a bachelor's degree.[81] Graduates of such programs, particularly in the engineering technologies, can earn more than $50,000 per year.[82]

According to National Student Clearinghouse data, community college enrollment has dropped by 1.6 million students since its peak year of 2010–11. In 2017, 88% of community colleges surveyed were facing declining enrollments.[83] A The New York Times report in 2017 suggested that of the nation's 18 million undergraduates, 40% were attending community college; of these students, 62% were attending community college full-time, 40% of them worked at least 30 hours a week or more, and more than half lived at home to save money.[84]

The College Promise program, which exists in several forms in 24 states, is an effort to encourage community college enrollment.[85]

Liberal arts colleges

Four-year institutions emphasizing the liberal arts are liberal arts colleges. They traditionally emphasize interactive instruction. They are known for being residential and for having smaller enrollment and lower student-to-faculty ratios than universities. Most are private, although there are public liberal arts colleges. Some offer experimental curricula, such as Hampshire College, Beloit College, Bard College at Simon's Rock, Pitzer College, Sarah Lawrence College, Grinnell College, Bennington College, New College of Florida, and Reed College.[86]

For-profit colleges

For-profit higher education (known as for-profit college or proprietary education) refers to higher education institutions operated by private, profit-seeking businesses. Students were "attracted to the programs for their ease of enrollment and help obtaining financial aid," but "disappointed with the poor quality of education...."[87][88] University of Phoenix has been the largest for-profit college in the US.[89] Since 2010, for-profit colleges have received greater scrutiny from the US government, state Attorneys General, the media, and scholars.[90] Notable business failures include Corinthian Colleges (2015), ITT Educational Services (2016), Education Management Corporation also known as EDMC (2017), and Education Corporation of America (2018).[91]

Funding of universities and colleges

Sources of funds

US colleges and universities receive their funds from many sources, including tuition, federal Title IV funds, state funds, and endowments.[92][93][94]

State government

The major source of funding for public institutions of higher education is direct support from the state. The levels of state support roughly correlate with the population of the state. For example, with a population nearly 40 million, the state of California allocates more than $15 billion on higher education. At the other extreme, Wyoming allocates $384 million for its 570,000 citizens.[95]

Institutional donors and endowments

Private giving supports both private and public institutions. Gifts come in two forms, current use and endowment. Both types of gifts are usually constrained according to a contract between the donor and the institution.

Private institutions tend to be more reliant on private giving.[96]

- Harvard University $40.9 billion

- University of Texas $30.88 billion

- Princeton University $25.9 billion

At the other extreme, the HBCU Fayetteville State University, has an endowment of $22 million.[96]

Private philanthropy can be controversial. At the University of Maryland, Northrop Grumman has funded a cybersecurity concentration, designs the curriculum in cybersecurity, provides computers and pays some cost of a new dorm. At Ohio State, IBM partnered to teach big data analytics. Murray State University's engineering program was supported by computer companies. The College of Nanoscale Science and Engineering at State University of New York in Albany, received billions of dollars in private sector investment.[97]

Student costs and funding

In 2016, average estimated annual student costs (excluding books) were $16,757 at public institutions, $43,065 at private nonprofit institutions, and $23,776 at private for-profit institutions. Between 2006 and 2016, prices at public colleges and universities rose 34 percent above inflation, and prices at private nonprofit institutions rose 26 percent above inflation.[98]

Students receive scholarships, student loans, or grants to offset costs out-of-pocket. Several states offer scholarships that allow students to attend free of tuition or at lower cost, for example the HOPE Scholarship in Georgia and the Bright Futures Scholarship Program in Florida. Some private colleges and universities offer full need-based financial aid, so that admitted students only have to pay as much as their families can afford (based on the university's assessment of their income).[99][100][101] In most cases, the barrier of entry for students who require financial aid is set higher, a practice called need-aware admissions. Universities with exceptionally large endowments may combine need-based financial aid with need-blind admission, in which students who require financial aid have equal chances to those who do not.

Financial assistance comes in two major forms: grant programs and loan programs. Grant programs consist of money the student receives to pay for higher education that does not need to be paid back; loan programs consist of money the student receives to pay for school that must be paid back. Public higher education institutions (which are partially funded through state government appropriation) and private higher education institutions (which are funded exclusively through tuition and private donations) offer grant and loan financial assistance programs. Grants to attend public schools are distributed through federal and state governments, and through the schools themselves; grants to attend private schools are distributed through the school itself (independent organizations, such as charities or corporations also offer grants that can be applied to both public and private higher education institutions).[102] Loans can be obtained publicly through government sponsored loan programs or privately through independent lending institutions.

Grants, scholarships, loans and work study programs

Grant programs and work study programs are divided into two major categories: Need-based financial awards and merit-based financial awards. Most state governments provide need-based scholarship programs, while a few also offer merit-based aid.[103] Several need-based grants are provided through the federal government based on information provided on a student's Free Application for Federal Student Aid or FAFSA.[104] The federal Pell Grant is a need-based grant available from the federal government. The federal government had two other grants that were a combination of need-based and merit-based: the Academic Competitiveness Grant, and the National SMART Grant, but the SMART grant was abolished in 2011 with the last grant awarded in June 2011. In order to receive one of these grants a student must be eligible for the Pell Grant, meet specific academic requirements, and be a US citizen.[102]

Eligibility for work study programs is also determined by information collected on the student's FAFSA.[102]

Many companies offer tuition reimbursement plans for their employees, to make benefits package more attractive, to upgrade the skill levels and to increase retention.[105]

In 2012, total student loans exceeded consumer credit card debt for the first time in history.[106] In late 2016, the total estimated US student loan debt exceeded $1.4 trillion.[107]

Student loans can be divided into two categories: federal student loans and private student loans. Federal student loans may be:

A student's eligibility for any of these loans, as well as the amount of the loan itself is determined by information on the student's FAFSA. The former Federal Perkins Loan program expired in 2017.[108]

Statistics

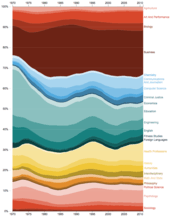

The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) and National Student Clearinghouse, show that college enrollment has declined since a peak in 2010–11 and is projected to continue declining or be stagnant for the next two decades.[109][110][111][112][113][114]

US educational statistics are provided by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), part of the Department of Education. The number of Title IV-eligible, degree-granting institutions peaked at 4,726 in 2012 with 3,026 4-year institutions and 1,700 2-year institutions: by 2016–17, the total had declined to 4,360 institutions with only 2832 4-year institutions and 1528 2-year institutions existing. [1] The enrollment at postsecondary institutions, participating in Title IV, peaked at just over 21.5 million students in 2010. l[115]

| Year | Fall enrollment[115] | Degree-granting institutions[1] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (all postsecondary) | (degree-granting) | (total) | (4-year) | (2-year) | |

| 2010–11 | 21,591,742 | 21,019,438 | 4,599 | 2,870 | 1,729 |

| 2011–12 | 21,573,798 | 21,010,590 | 4,706 | 2,968 | 1,738 |

| 2012–13 | 21,148,181 | 20,644,478 | 4,726 | 3,026 | 1,700 |

| 2013–14 | 20,848,050 | 20,376,677 | 4,724 | 3,039 | 1,685 |

| 2014–15 | 20,664,180 | 20,209,092 | 4,627 | 3,011 | 1,616 |

| 2015–16 | 20,400,164 | 19,988,204 | 4,583 | 3,004 | 1,579 |

| 2016–17 | 20,224,069 | 19,841,014 | 4,360 | 2,832 | 1,528 |

A US Department of Education longitudinal survey of 15,000 high school students in 2002 and 2012, found that 84% of the 27-year-old students had some college education, but only 34% achieved a bachelor's degree or higher; 79% owe some money for college and 55% owe more than $10,000; college dropouts were three times more likely to be unemployed than those who finished college; 40% spent some time unemployed and 23% were unemployed for six months or more; and 79% earned less than $40,000 per year.[116][117]

Declining enrollment, mergers, and campus closures

Falling birth rates result in fewer people graduating from high school. The number of high school graduates grew 30% from 1995 to 2013, then peaked at 3.5 million; projections show it holding at that level in the next decade.[118] Liberal arts programs have been declining for decades. From 1967 to 2018, college students majoring in the liberal arts declined from 20 percent to 5 percent.[119]

Since 2011, there has been a significant decline in the number of students enrolled in postsecondary education in the United States. That is more than 2 million people.[120] In the fall of 2019, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, enrollment declined 1.3% from 2018, approximately 231,000 less students.[121] Researchers hypothesize that the primary factors leading to this drop in enrollment are low birth rates over the last couple decades, a more successful economy, and the increasing cost of postsecondary education coupled with a decrease in financial aid and student debt.[120][122] Some potential students are also questioning the value of a postsecondary education and whether it is necessary to gain employment.[120][122] In 2018, the National Center for Education Statistics projected stagnant enrollment patterns until at least 2027.[111] Demographer Nathan Grawe projected that lower birth rates following the Great Recession of 2008 would result in a 15 percent enrollment loss, beginning in 2026.[109]

In 2019, the National Center for Education Statistics continued to project that higher education enrollment would remain stagnant, but white enrollment would drop 8 percent from 2016 to 2027. The report projected black enrollment to increase by 6 percent, Hispanic enrollment to increase 14 percent, Asian/Pacific Islander enrollment to increase 7 percent, and American Indian/Alaska Native enrollment to decrease 9 percent during the same period.[114] In March 2019, Moody's warned that enrollment declines could lead to more financial problems for the higher education industry.[123] In a 2019 survey by Inside Higher Ed, nearly one in seven college presidents said their campus could close or merge within five years.[124] In April 2019, Connecticut presented a plan to consolidate their community colleges with their accreditor.[125]

In "The Higher Education Apocalypse", U.S. News & World Report education reporter Lauren Camera speculated that recent closings of schools in New England might be the beginning of a rash of college closures.[126] An analysis of federal data from The Chronicle of Higher Education shows "about half a million students have been displaced by college closures, which together shuttered more than 1,200 campuses."[127]

Admission process

Students can apply to some colleges using the Common Application. With a few exceptions, most undergraduate colleges and universities maintain the policy that students are to be admitted to (or rejected from) the entire college, not to a particular department or major. (This is unlike college admissions in many European countries, as well as graduate admissions.) Some students, rather than being rejected, are "wait-listed" for a particular college and may be admitted if another student who was admitted decides not to attend the college or university. The five major parts of admission are ACT/SAT scores, grade point average, college application, essay, and letters of recommendation. The SAT's usefulness in the admissions process is controversial.[129][130]

Legacies and large donors

Admissions at elite schools include preferences to alumni and large investors.[131][132][133] Legislators have asked for transparency with donors and college admissions, but there are several groups that oppose it.[134] Inside Higher Ed's 2018 survey of college admissions directors found that 42 percent of private colleges and universities used legacy status as a factor in admissions decisions.[135]

International study and student exchange

In 2016–17, 332,727 US students studied abroad for credit. Most took place in Europe, with 40 percent of students studying in five countries: the United Kingdom, Italy, Spain, France, and Germany.[136] The US is the most popular country in the world for attracting students from other countries, according to UNESCO, with 16% of all international students going to the US (the next highest is the UK with 11%).[137] 671,616 foreign students enrolled in American colleges in 2008–09.[137][138] This figure rose to 723,277 in 2010–11. The largest number, 157,558, came from China.[139] According to Uni in the USA, despite "exorbitant" costs of US universities, higher education in America remains attractive to international students due to "generous subsidies and financial aid packages that enable students from even the most disadvantaged backgrounds to attend the college of their dreams".[140]

Government coordination

Coordination institutions

Every state has an entity designed to promote coordination and collaboration between higher education institutions. A few are listed: Alabama Commission on Higher Education, California Postsecondary Education Commission, Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, Washington State Higher Education Coordinating Board, The Georgia Department of Technical and Adult Education.

Academic labor and adjunctification

Until the mid-1970s, when federal expenditures for higher education fell, there were routinely more tenure-track jobs than Ph.D. graduates. In the 1980s and 1990s there were significant changes in the economics of academic life. Despite rising tuition rates and growing university revenues, professorial positions were replaced with poorly paid adjunct positions and graduate-student labor.[141]

With academic institutions producing Ph.D.s in greater numbers than the number of tenure-track positions they intended to create, administrators were cognizant of the economic effects of this arrangement. Sociologist Stanley Aronowitz wrote: "Basking in the plenitude of qualified and credentialed instructors, many university administrators see the time when they can once again make tenure a rare privilege, awarded only to the most faithful and to those whose services are in great demand".[142] Aggravating the problem, those few academics who do achieve tenure are often determined to stay put as long as possible, refusing lucrative incentives to retire early.[143]

In 2017, 17% of faculty were tenured. 89% of adjunct professors worked at more than one job. An adjunct was paid an average of $2,700 for a single course. While student-faculty ratios remained the same since 1975, administrator-student ratio went from 1–84 to 1–68.[144] In 2018, the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) reported that 73 percent of all faculty positions were filled by adjuncts.[145]

Adjunct organizations include the Coalition for Contingent (COCAL), the New Faculty Majority, and SEIU Faculty Forward.[146][147] The American Federation of Teachers and the International Brotherhood of Teamsters have also organized contingent academic labor.[148][149]

Athletics

_rushes_for_one_of_two_touchdowns_while_being_persued_by_Army_defenders_Cason_Shrode_(54)_and_Taylor_Justice_(42).jpg)

College athletics in the US is a two-tiered system. The first tier includes sports sanctioned by one of the collegiate sport governing bodies. Some of these collegiate sports governing organizations like the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) are umbrella non-profit organizations that govern multiple sports. Additionally, the first tier is characterized by selective participation, since only the elite programs in their sport are able to participate; some colleges offer athletic scholarships to intercollegiate sports competitors. The second tier includes intramural and recreational sports clubs, which are available to more of the student body. Competition between student clubs from different colleges, not organized by and therefore not representing the institutions or their faculties, may also be called "intercollegiate" athletics or simply college sports.[150]

The largest collegiate sport governing body in the first tier is the NCAA, which regulates athletes of 1,268 institutions across the US and Canada. The NCAA uses a three-division system of Division I, Division II, and Division III. Division I and Division II schools can offer scholarships to athletes for playing a sport, while Division III schools cannot offer any athletic scholarships.[151] Division I schools, which generally are larger than either Division II or III institutions, must further meet additional requirements: among them, they must field teams in at least seven sports for men and seven for women or six for men and eight for women, with at least two team sports for each gender.[152] Each division is then further divided into several conferences for regional league play. The names of these conferences, such as the Ivy League, are also metonyms for their respective schools.[153]

College sports are popular on regional and national scales, at times competing with professional championships for prime broadcast, print coverage. In most states, the person with the highest taxpayer-provided base salary is a public college football or basketball coach. This does not include coaches at private colleges.[154] The average university sponsors at least 20 different sports and offers a wide variety of intramural sports. There are approximately 400,000 men and women student-athletes that participate in sanctioned athletics each year.[155]

Issues confronting higher education in the United States

Entrance routes and procedures for choosing a college or university, their rankings and the financial value of degrees are being discussed. This leads to discussions on socioeconomic status and race ethnicity and gender. From the student perspective, issues include colleges failing to teach basic skills such as critical thinking,[156] the wide ranges of remuneration and underemployment among the various degrees,[157][158][159][160] rising tuition and increasing student loan debt,[161][162] austerity in state and local spending, the adjunctification of academic labor,[163][164] student poverty and hunger,[165] along with credentialism and educational inflation.[166]

See also

- Academic ranks in the United States

- Association of American Universities

- Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education

- College admissions in the United States

- Education in the United States

- G.I. American universities

- Hispanic-serving institution

- Historically black colleges and universities

- History of education in the United States

- History of education in the United States: Bibliography

- Land-grant university

- Liberal arts colleges in the United States

- List of Catholic universities and colleges in the United States

- Men's colleges in the United States

- Morrill Land-Grant Acts

- National Collegiate Athletic Association

- Pell Grant

- Transfer admissions in the United States

- Women's colleges in the United States

- Work college

References

- "Degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by control and level of institution: Selected years, 1949-50 through 2016-17". NCES. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- Nataša Bakić-Mirić; Davronzhon Erkinovich Gaipov (February 27, 2015). Current Trends and Issues in Higher Education: An International Dialogue. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 154–. ISBN 978-1-4438-7564-6.

- Vedder, Richard. "The Three Reasons College Sports Is An Ugly Business". Forbes.

- Thelin, John R. (April 2, 2019). A History of American Higher Education (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1421428833.

- Wilder, Craig David (September 2, 2014). Ebony and Ivy (1st ed.). Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781608194025.

- David B. Potts, "American colleges in the nineteenth century: From localism to denominationalism." History of Education Quarterly (1971): 363–380, data on pp. 373, 374. in JSTOR.

- David B. Potts, Baptist colleges in the development of American society, 1812–1861 (1988).

- Frederick Rudolph, The American College and University: A History (1991) pp. 3–22

- Michael Katz, "The Role of American Colleges in the Nineteenth Century", History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 2 (Summer, 1983), pp. 215–223 in JSTOR, summarizing Colin B. Burke, American Collegiate Populations: A Test of the Traditional View (New York University Press, 1982) and Peter Dobkin Hall, The Organization of American Culture: Private Institutions, Elites, and the Origins of American Nationality (New York University Press, 1982)

- LaBelle, Jeffrey (2011). Catholic Colleges in the 21st Century: A Road Map for Campus Ministry. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-1893757899.

- John Rodden, "Less 'Catholic,' More 'catholic'? American Catholic Universities Since Vatican II." Society (2013) 50#1 pp. 21–27.

- S.J. Currie, and L. Charles. "Pursuing Jesuit, Catholic identity and mission at US Jesuit colleges and universities." Catholic Education: A Journal of Inquiry and Practice (2011) 14#3 pp. 4ff online

- Matthew Thomas Larsen, The Duty and Right of the Diocesan Bishop to Watch Over the Preservation and Strengthening of the Catholic Character of Catholic Universities in His Diocese" (PhD dissertation Catholic University of America, 2012)

- Hillison, John (1995). "The Coaltion that Supported the Smith-Hughes Act or a Case for Strange Bedfellows" (PDF). Journal of Career and Technical Education. 11 (2): 4–11. doi:10.21061/jcte.v11i2.582. Retrieved June 22, 2019.

- Kelchen, Robert (2018). Higher Education Accountability. Batimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 42. ISBN 9781421424736. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- Leonard V. Koos, The Junior College Movement (1924).

- Cohen; Brawer (2003). The American Community College (4th ed.). pp. 13–14.

- Jesse P. Bogue, ed. American Junior Colleges (American Council on Education, 1948)

- Cohen; Brawer (2013). The American Community College (6th ed.).

- "11 Past and Present Social Movements Led By College Students". Freshu.io. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- Angulo, A. J. (January 27, 2016). Diploma Mills: How For-Profit Colleges Stiffed Students, Taxpayers, and the American Dream. JHU Press. ISBN 9781421420073 – via Google Books.

- Korn, Melissa (September 7, 2016). "ITT Technical Institute Shuts Down After Government Cut Off New Funding". Wsj.com. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- "'Fail State' Delves into the Shadowy World of For-Profit Colleges". The Texas Observer. October 27, 2017.

- Friedman, Jordan (January 11, 2018). "Study: More Students Are Enrolling in Online Courses". US News & World Report. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- "Report: One in Four Students Enrolled in Online Courses". OLC. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- "Reports finds rising competition in online education market". Insidehighered.com. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- "Harvard Offers First Coding Boot Camp - Inside Higher Ed". www.insidehighered.com.

- "Universities". Trilogy Education Services.

- "Online learning fails to deliver, finds report aimed at discouraging politicians from deregulating - Inside Higher Ed". www.insidehighered.com. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- Protopsaltis, Spiros; Baum, Sandy (January 2019). "Does Online Education Live Up to Its Promise? A Look at the Evidence and Implications for Federal Policy" (PDF).

- Hill, Phil (January 27, 2019). "Deeply Flawed GMU Report on Online Education Asks Good Questions But Provides Misguided Analysis". e-Literate.

- Bozkurt, Aras; Akgun-Ozbek, Ela; Yilmazel, Sibel; Erdogdu, Erdem; Ucar, Hasan; Guler, Emel; Sezgin, Sezan; Karadeniz, Abdulkadir; Sen-Ersoy, Nazife; Goksel-Canbek, Nil; Dincer, Gokhan Deniz; Ari, Suleyman; Aydin, Cengiz Hakan (January 20, 2015). "Trends in distance education research: A content analysis of journals 2009-2013". The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning. 16 (1). doi:10.19173/irrodl.v16i1.1953.

- Zemsky, Robert (2014). "With a MOOC MOOC here and a MOOC MOOC there, here a MOOC, there a MOOC, everywhere a MOOC MOOC". Journal of General Education. 63 (4): 237–243. doi:10.1353/jge.2014.0029. JSTOR 10.5325/jgeneeduc.63.4.0237.

- "Study offers data to show MOOCs didn't achieve their goals - Inside Higher Ed". www.insidehighered.com. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- Carey, Kevin (April 1, 2019). "The Creeping Capitalist Takeover of Higher Education". Huffpost. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- "Networked U.'s: This Is What Will Save Higher Ed". November 8, 2017.

- "PEPS Closed School Monthly Reports". www2.ed.gov. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- Stowe, Kristin; Komasara, David (July 2016). "An Analysis of Closed Colleges and Universities". Planning for Higher Education Journal. 44 (4). Retrieved April 2, 2019 – via ProQuest.

- cmaadmin (February 21, 2017). "Court Rules Against Accrediting Agency of ITT Tech, Corinthian Colleges". diverseeducation.com. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- Douglas-Gabriel, Danielle (December 6, 2018). "Virginia College and Brightwood College closing; for-profit operator cites dwindling enrollment". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- "Green Mountain College tried numerous strategies but is still closing". www.insidehighered.com. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- Harris, Adam (December 5, 2017). "Moody's Downgrades Higher Ed's Outlook From 'Stable' to 'Negative'". Retrieved January 27, 2019 – via The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- "Moody's: Declining Enrollment Is Squeezing Tuition Revenue - Inside Higher Ed". www.insidehighered.com. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

- Lombardo, Cara (May 1, 2019). "McGraw-Hill to Merge With Rival Textbook Publisher" – via www.wsj.com.

- "Behind Berkeley's Semester of Hate". Nytimes.com. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- "White supremacy is turning up on campus in speeches and leaflets". Insidehighered.com. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- "More Diversity Means More Demands". Nytimes.com. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- "Colleges brace for more violence in wake of Charlottesville rally". Cbsnews.com. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- "College students unmasked as 'Unite the Right' protesters". Insidehighered.com. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- Stripling, Jack; Gluckman, Nell (August 16, 2017). "UVa Employee Suffers a Stroke After Campus Clash With White Supremacists". The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- "Opinion – What U.Va. Students Saw in Charlottesville". Nytimes.com. August 13, 2017. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- "Public universities are on solid ground to cancel Richard Spencer events, legal experts say". Insidehighered.com. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- Ford, Marcus (May 2017). "The Functions of Higher Education". American Journal of Economics and Sociology. 76 (3): 559–578. doi:10.1111/ajes.12187.

- "The Dirty Little Secret of Credential Inflation". The Chronicle of Higher Education. September 27, 2002.

- Collins, Randall (December 1971). "Functional and Conflict Theories of Educational Stratification". American Sociological Review. 36 (6): 1002–19. doi:10.2307/2093761. JSTOR 2093761.

- Subprime college educations

- "U21 Ranking of National Higher Education Systems 2018 - Universitas 21". universitas21.com. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- Phil Baty (September 16, 2010). "The World University Rankings: Measure by measure: the US is the best of the best". TSL Education Ltd. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- "Several countries launch campaigns to recruit research talent from U.S. and elsewhere". Insidehighered.com. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- "Senate Appropriations Bill Cuts NSF Funding". Insidehighered.com. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- "Proposal on indirect costs would put research universities in an impossible situation (essay)". Insidehighered.com. Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- Erica Snow (September 26, 2018). "Oxford, Cambridge Top Global University Rankings: Long-dominant U.S. schools facing stiffer competition from overseas". Wall Street Journal.

- O’Malley, Brendan. "US suffers worst global ranking performance in 16 years". universityworldnews.com. Retrieved June 24, 2019.

- Davis Whitman (February 13, 2017). "Vietnam Vets and a New Student Loan Program Bring New College Scams". The Century Foundation.

- Liz Robbins (May 5, 2016). "Students at Fake University Say They Were Collateral Damage in Sting Operation". New York Times.

- Robert Shireman (May 20, 2019). "The Policies That Work—and Don't Work—to Stop Predatory For-Profit Colleges". The Century Foundation.

- Onion, Rebecca (July 27, 2016). "19th-Century For-Profit Colleges Spawned Trump University". Slate.

- "A First Try at ROI: Ranking 4,500 Colleges". Center on Education and the Workforce. Georgetown University. November 5, 2019. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- Turnage, Clara (July 10, 2017). "Most Republicans Think Colleges Are Bad for the Country. Why?". The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- "Republicans don't trust higher ed. That's a problem for liberal academics". Latimes.com. July 24, 2017. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- Hartle, Terry W. (July 19, 2017). "Why Most Republicans Don't Like Higher Education". The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- "New data explain Republican loss of confidence in higher education". Insidehighered.com. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- Mitch Daniels, February 6, 2018, Washington Post, Health care isn’t our only ludicrously expensive industry, Retrieved February 7, 2018, "... by evading accountability for quality, regulating it heavily, and opening a hydrant of public subsidies in the form of government grants and loans, we have constructed another system of guaranteed overruns ... pricing categories that have outpaced health care over recent decades are college tuition, room and board, and books...."

- "Survey: Most Americans think higher ed is headed in wrong direction". www.insidehighered.com.

- "Gallup, Bates report shows graduates want a sense of purpose in careers". www.insidehighered.com. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- "Not Impartial: Examining Accreditation Commissioners' Conflicts of Interest" (PDF). Economics21.org. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- e.g., Boston College, Dartmouth College, The College of William & Mary, and College of Charleston

- "Basic Classification Technical Details". Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. n.d. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- Yoder, Dezarae (February 25, 2013). "Marijuana illegal on campus despite Amendment 64". The Scribe.

- 34 C.F.R. 86; specifically 34 C.F.R. 86.100

- Beth Frerking, Community Colleges: For Achievers, a New Destination, The New York Times, April 22, 2007.

- Carnevale, Anthony (January 2020). "The Overlooked Value of Certificates and Associate's Degrees: What Students Need to Know Before They Go to College". Center on Education and the Workforce. Georgetown University. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

This report examines the labor-market value of associate’s degrees and certificate programs, finding that field of study especially influences future earnings for these programs since they are tightly linked with specific occupations.

- "Community colleges examining low and stagnant enrollments". Insidehighered.com. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- Gail O. Mellow, August 28, 2017, The New York Times, The Biggest Misconception About Today’s College Students, Retrieved August 28, 2017

- Kanter, Martha; Armstrong, Andra. "The College Promise: Transforming the Lives of Community College Students". League for Innovation in the Community College. Retrieved July 6, 2019.

- "Creative Curriculum". Hampshire College. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Unglesbee, Ben (April 1, 2019). "For-profit online students drawn by convenience but left 'disappointed'". EducationDive. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- Howarth, Robin; Stifler, Lisa (March 2019). "The Failings of Online For-profit Colleges: Findings from Student Borrower Focus Groups" (PDF). The Brookings Institution. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- Media, American Public. "The Story of the University of Phoenix". americanradioworks.publicradio.org.

- Armour, Stephanie; Zibel, Alan (January 13, 2014). "For-Profit College Probe Expands". Wsj.com. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- "Closure of Education Corporation of America raises questions about oversight and support for students". www.insidehighered.com.

- "A Lost Decade in Higher Education Funding". Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. August 22, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- "Federal and State Funding of Higher Education". pew.org. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- https://www.acenet.edu/news-room/Documents/Understanding-Endowments-White-Paper.pdf

- https://education.illinoisstate.edu/grapevine/tables/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "U.S. and Canadian Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year (FY) 2018 Endowment Market Value and Change* in Endowment Market Value from FY17 to FY18". 2018.

- Belkin, Douglas (April 7, 2014). "Corporate Cash Alters University Curricula". WSJ. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- "Digest of Education Statistics, 2016 - Introduction". Nces.ed.gov. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on March 12, 2015. Retrieved March 14, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 30, 2015. Retrieved August 29, 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Elite Colleges Struggle To Recruit Smart, Low-Income Kids January 9, 2013, Shankar Vedantam, NPR.org

- College Board (2007). "3". Meeting College Costs: A Workbook for Families. New York: College Board.

- Jennifer Levitz; Scott Thurm (December 20, 2012), "Shift to Merit Scholarships Stirs Debate", The Wall Street Journal, pp. A1, A16

- "Free Application for Federal Student Aid". FAFSA on the Web.

- Flaherty Manchester, Colleen (2012). "General human capital and employee mobility: How tuition reimbursement increases retention through sorting and participation". Industrial & Labor Relations Review. 65 (4): 951–974. doi:10.1177/001979391206500408.

- Kingkade, Tyler (January 9, 2013). "Paying Off $26,500 In Debt In Two Years: How Brian McBride Did It". HUFF POST. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- Berman, Jillian. "Watch America's student-loan debt grow $2,726 every second". Marketwatch.com. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- "Perkins Loan Program Expires After Extension Bill is Blocked". The Student Loan Report. October 3, 2017.

- "New book argues most colleges are about to face significant decline in prospective students - Inside Higher Ed". www.insidehighered.com.

- "Why Is Undergraduate College Enrollment Declining?". NPR.org.

- "The Condition of Education" (PDF). National Center for Education Studies. May 2018. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- "Intensive English Enrollments in U.S. Drop 20% - Inside Higher Ed". www.insidehighered.com.

- Blog, N. S. C. (December 13, 2018). "Fall 2018 Overall Postsecondary Enrollments Decreased 1.7 Percent from Last Fall". studentclearinghouse.org. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- "Projections of Education Statistics to 2027" (PDF). National Center for Education Studies. February 2019. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- "Total fall enrollment in all postsecondary institutions participating in Title IV programs and annual percentage change in enrollment, by degree-granting status and control of institution: 1995 through 2016". NCES. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- "Education Longitudinal Study of 2002 (ELS: 2002): A First Look at 2002 High School Sophomores 10 Years Later First Look" (PDF). NCES 2014-363. U.S. Department of Education. January 2014. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- Jordan Weissmann, Atlantic Monthly, January 14, 2014, Highly Educated, Highly Indebted: The Lives of Today's 27-Year-Olds, In Charts: A new study by the Department of Education offers up a statistical picture of young-adult life in the wake of the Great Recession, Accessed January 26, 2014

- see "Knocking at the College Door, 9th Edition: Projections of High School Graduates" Dec 6, 2016 .

- "Liberal arts face uncertain future at nation's universities". June 4, 2018.

- Nietzel, Michael T. (December 16, 2019). "College Enrollment Declines Again. It's Down More Than Two Million Students In This Decade". Forbes. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- "Current Term Enrollment Estimates - Fall 2019". National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. December 16, 2019. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- "Fewer Students Are Going To College. Here's Why That Matters". NPR.org. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- "Moody's: Slow enrollment gains raise colleges' financial risk". Education Dive. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- "2019 Survey of College and University Presidents - Inside Higher Ed". www.InsideHigherEd.com. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- "Connecticut community colleges faculty and administration at odds over proposed consolidation". www.InsideHigherEd.com. April 17, 2019. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- Camera, Lauren (March 22, 2019). "The Higher Education Apocalypse". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- "How America's College-Closure Crisis Leaves Families Devastated". The Chronicle of Higher Education. April 4, 2019. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- "Top 100 - Lowest Acceptance Rates". U.S. News. Archived from the original on February 23, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- Buckley, Jack; Letukas, Lynn; Wildavsky, Ben (2017), Measuring Success: Testing, Grades, and the Future of College Admissions, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 344, ISBN 9781421424965

- Coates, Ken; Morrison, Bill (2015), What to Consider If You're Considering College: New Rules for Education and Employment, Dundurn, p. 280, ISBN 978-1459723726

- Wong, Alia (March 12, 2019). "Why the College-Admissions Scandal Is So Absurd". The Atlantic. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- Golden, Daniel (March 12, 2019). "How the Rich Really Play, 'Who Wants To Be An Ivy Leaguer?'". ProPublica. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- Wermund, Benjamin. "Admissions scandal reveals why America's elite colleges are under fire". POLITICO. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- "Senator offers legislation to respond to admissions scandal | Inside Higher Ed". www.insidehighered.com. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- "Study shows significant impact of legacy status in admissions, and that the applicants have been strong - Inside Higher Ed". www.InsideHigherEd.com. April 22, 2019. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- "Trends in U.S. Study Abroad". NAFSA. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- "Global Flow of Tertiary-Level Students". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2013.

- Marklein, Mary Beth (November 16, 2009). "More U.S. students going abroad, and vice versa". USA Today. pp. 5D.

- Marklein, Mary Beth (November 14, 2010). "More foreign students in USA". Melbourne, Florida: Florida Today. pp. 4A.

- "Paying for US uni". UNI. in the USA and Beyond. 2012. Archived from the original on September 23, 2013. Retrieved October 7, 2013.

- Stainburn, Samantha (January 3, 2010). "The Case of the Vanishing Full-Time Professor". The New York Times. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- Aronowitz, Stanley. The Knowledge Factory: Dismantling the Corporate University and Creating True Higher Learning, p. 76. ISBN 0807031232.

- Marcus, Jon (October 9, 2015). "Aging faculty who won't leave thwart universities' attempts to cut costs". Hechinger Report. Teachers College at Columbia University. Retrieved May 4, 2018.

Protected by tenure that prevents them from being dismissed without cause, and with no mandatory retirement age, a significant proportion of university faculty isn’t going anywhere.

- Reynolds, Glenn Harlan (February 19, 2017). "President Trump should take pity on poor PhD". Florida Today. Melbourne, Florida. pp. 19A. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- "Data Snapshot: Contingent Faculty in US Higher Ed - AAUP". www.aaup.org.

- "COCAL". cocalinternational.org.

- "History - New Faculty Majority".

- AFTVoicesoncampus (April 16, 2018). "Why I'm ready to walk out: I can't afford to give students the attention they deserve". AFT Voices.

- "'Fed Up' Rutgers Faculty Protest Slow Contract Talks, Threaten to Strike - NJ Spotlight". www.njspotlight.com.

- Rosandich, Thomas (2002). Collegiate Sports Programs: A Comparative Analysis. Education. p. 476.

- "Bylaw 15.01.3 Institutional Financial Aid" (PDF). 2012–13 NCAA Division III Manual. NCAA. p. 107. Retrieved December 19, 2012.

- "The Official Web Site of the NCAA". NCAA.org. Archived from the original on January 17, 2012. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- "Princeton Campus Guide – Ivy League". Retrieved April 26, 2007.

- Rich, Bobby. "The 25 Highest-Paid College Coaches". The Quad.

We focus solely on what universities pay their coaches as their base salary, and do not include bonuses or any outside income.

- Rosandich, Thomas (2002). Collegiate Sports Programs: A Comparative Analysis. Education. p. 474.

- "Employers Judge Recent Graduates Ill-Prepared for Today's Workplace, Endorse Broad and Project-Based Learning as Best Preparation for Career Opportunity and Long-Term Success" (Press release). Washington, DC: Association of American Colleges and Universities. January 20, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- "Occupational Outlook Handbook". Bureau of Labor Statistics. Department of Labor.

- The Labor Market for Recent College Graduates, Federal Reserve Bank of New York

- Carnevale, Anthony; Cheah, Ban (2018), Five Rules of the College and Career Game, Georgetown University, retrieved May 16, 2018

- "Underemployment: Research on the Long-Term Impact on Careers". Burning Glass Technologies and the Strada Institute for the Future of Work. October 2018. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- Riley Griffin, "The Student Loan Debt Crisis Is About to Get Worse: The next generation of graduates will include more borrowers who may never be able to repay." Bloomberg October 17, 2018

- "More in U.S. see drug addiction, college affordability and sexism as 'very big' national problems". PewResearch.org. October 22, 2018. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- Jenkins, Rob (December 15, 2014). "Straight Talk About 'Adjunctification'". Retrieved April 17, 2019 – via The Chronicle of Higher Education.

- "Herb Childress discusses his new book, 'The Adjunct Underclass'". www.insidehighered.com. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- McKenna, Laura (January 14, 2016). "The Gravity of the Hunger Problem on College Campuses". The Atlantic.

- "The Curse of Credentialism". The NYU Dispatch. November 17, 2017. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

Credentialism, or degree inflation, as it is sometimes referred to, has been a growing problem globally for the better part of the last decade.

Further reading

- Cole, Jonathan R. (2016). Toward a More Perfect University. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1610392655.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Higher education in the United States. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Touring prestigious and notable universities in the U.S.. |