Education in Islam

Education has played a central role in Islam since early times, owing in part to the centrality of scripture and its study in the Islamic tradition. Before the modern era, education would begin at a young age with study of Arabic and the Quran. Some students would then proceed to training in tafsir (Quranic exegesis) and fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), which was seen as particularly important. For the first few centuries of Islam, educational settings were entirely informal, but beginning in the 11th and 12th centuries, the ruling elites began to establish institutions of higher religious learning known as madrasas in an effort to secure support and cooperation of the ulema (religious scholars). Madrasas soon multiplied throughout the Islamic world, which helped to spread Islamic learning beyond urban centers and to unite diverse Islamic communities in a shared cultural project.[1] Madrasas were devoted principally to study of Islamic law, but they also offered other subjects such as theology, medicine, and mathematics.[2] Muslims historically distinguished disciplines inherited from pre-Islamic civilizations, such as philosophy and medicine, which they called "sciences of the ancients" or "rational sciences", from Islamic religious sciences. Sciences of the former type flourished for several centuries, and their transmission formed part of the educational framework in classical and medieval Islam. In some cases, they were supported by institutions such as the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, but more often they were transmitted informally from teacher to student.[1] While formal studies in madrasas were open only to men, women of prominent urban families were commonly educated in private settings and many of them received and later issued ijazas (diplomas) in hadith studies, calligraphy and poetry recitation. Working women learned religious texts and practical skills primarily from each other, though they also received some instruction together with men in mosques and private homes.[3]

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

|

Etymology

In Arabic three terms are used for education. The most common is ta'līm, from the root 'alima, which means knowing, being aware, perceiving and learning. Another term is Tarbiyah from the root of raba, which means spiritual and moral growth based on the will of God. The third term is Ta'dīb from the root aduba which means to be cultured or refined in social behavior.[4]

Education in pre-modern Islam

The centrality of scripture and its study in the Islamic tradition helped to make education a central pillar of the religion in virtually all times and places in the history of Islam.[1] The importance of learning in the Islamic tradition is reflected in a number of hadiths attributed to Muhammad, including one that instructs the faithful to "seek knowledge, even in China".[1] This injunction was seen to apply particularly to scholars, but also to some extent to the wider Muslim public, as exemplified by the dictum of Al-Zarnuji, "learning is prescribed for us all".[1] While it is impossible to calculate literacy rates in pre-modern Islamic societies, it is almost certain that they were relatively high, at least in comparison to their European counterparts.[1]

_2006.jpg)

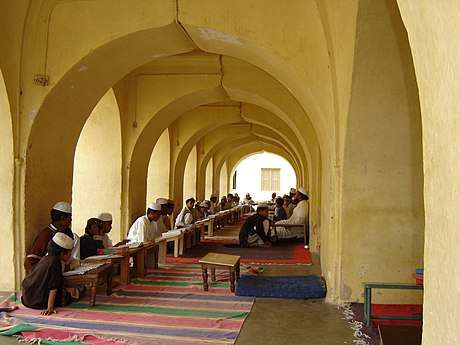

Education would begin at a young age with study of Arabic and the Quran, either at home or in a primary school, which was often attached to a mosque.[1] Some students would then proceed to training in tafsir (Quranic exegesis) and fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), which was seen as particularly important.[1] Education focused on memorization, but also trained the more advanced students to participate as readers and writers in the tradition of commentary on the studied texts.[1] It also involved a process of socialization of aspiring scholars, who came from virtually all social backgrounds, into the ranks of the ulema.[1]

For the first few centuries of Islam, educational settings were entirely informal, but beginning in the 11th and 12th centuries, the ruling elites began to establish institutions of higher religious learning known as madrasas in an effort to secure support and cooperation of the ulema.[1] Madrasas soon multiplied throughout the Islamic world, which helped to spread Islamic learning beyond urban centers and to unite diverse Islamic communities in a shared cultural project.[1] Nonetheless, instruction remained focused on individual relationships between students and their teacher.[1] The formal attestation of educational attainment, ijaza, was granted by a particular scholar rather than the institution, and it placed its holder within a genealogy of scholars, which was the only recognized hierarchy in the educational system.[1] While formal studies in madrasas were open only to men, women of prominent urban families were commonly educated in private settings and many of them received and later issued ijazas in hadith studies, calligraphy and poetry recitation.[3][5] Working women learned religious texts and practical skills primarily from each other, though they also received some instruction together with men in mosques and private homes.[3]

Madrasas were devoted principally to study of law, but they also offered other subjects such as theology, medicine, and mathematics.[2][6] The madrasa complex usually consisted of a mosque, boarding house, and a library.[2] It was maintained by a waqf (charitable endowment), which paid salaries of professors, stipends of students, and defrayed the costs of construction and maintenance.[2] The madrasa was unlike a modern college in that it lacked a standardized curriculum or institutionalized system of certification.[2]

Muslims distinguished disciplines inherited from pre-Islamic civilizations, such as philosophy and medicine, which they called "sciences of the ancients" or "rational sciences", from Islamic religious sciences.[1] Sciences of the former type flourished for several centuries, and their transmission formed part of the educational framework in classical and medieval Islam.[1] In some cases, they were supported by institutions such as the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, but more often they were transmitted informally from teacher to student.[1]

The University of Al Karaouine, founded in 859 AD, is listed in The Guinness Book Of Records as the world's oldest degree-granting university.[7] The Al-Azhar University was another early university (madrasa). The madrasa is one of the relics of the Fatimid caliphate. The Fatimids traced their descent to Muhammad's daughter Fatimah and named the institution using a variant of her honorific title Al-Zahra (the brilliant).[8] Organized instruction in the Al-Azhar Mosque began in 978.[9]

Ideas

Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas described the Islamic purpose of education as a balanced growth of the total personality through training the spirit, intellect, rational self, feelings and bodily senses such that faith is infused into the whole personality.[4]

Seyyed Hossein Nasr stated that, while education does prepare humankind for happiness in this life, "its ultimate goal is the abode of permanence and all education points to the permanent world of eternity".[4]

According to the Nahj al-Balagha, there are two kinds of knowledge: knowledge merely heard and that which is absorbed. The former has no benefit unless it is absorbed. The heard knowledge is gained from the outside and the other is absorbed knowledge means the knowledge that raised from nature and human disposition, referred to the power of innovation of a person.[10]

The Quran is the optimal source of knowledge.[11] For teaching Quranic traditions, the Maktab as elementary school emerged in mosques, private homes, shops, tents, and even outside.[12][4]

The Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) has organized five conferences on Islamic education: in Mecca (1977), Islamabad (1980), Dhaka (1981), Jakarta (1982), and Cairo (1987).[13]

Modern Education in Islam

In general, minority religious groups often have more education than a country's majority religious group, even more so when a large part of that minority are immigrants.[14] This trend applies to Islam: Muslims in North America and Europe have more formal years of formal education than Christians.[15] Furthermore, Christians have more formal years of education in many majority Muslim countries, such as in sub-Saharan Africa.[15] However, global averages of education are far lower for Muslims than Jews, Christians, Buddhists and people unaffiliated with a religion.[14] However, younger Muslims have made much larger gains in education than any of these other groups.[14]

There is a perception of a large gender gap in majority Islam countries, but this is not always the case.[16] In fact, the quality of female education is more closely related to economic factors than religious factors.[16] And, although the gender gap in education is real, it has been continuing to shrink in recent years.[17] Women in all religious groups have made much larger educational gains in recent generations than men.[14]

See also

References

- Jonathan Berkey (2004). "Education". In Richard C. Martin (ed.). Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World. MacMillan Reference USA.

- Lapidus, Ira M. (2014). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press (Kindle edition). p. 217. ISBN 978-0-521-51430-9.

- Lapidus, Ira M. (2014). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press (Kindle edition). p. 210. ISBN 978-0-521-51430-9.

- "Islam - History of Islamic Education, Aims and Objectives of Islamic Education". education.stateuniversity.

- Berkey, Jonathan Porter (2003). The Formation of Islam: Religion and Society in the Near East, 600–1800. Cambridge University Press. p. 227.

- Hallaq, Wael B. (2009). An Introduction to Islamic Law. Cambridge University Press. p. 50.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- The Guinness Book Of Records, Published 1998, ISBN 0-553-57895-2, p. 242

- Halm, Heinz. The Fatimids and their Traditions of Learning. London: The Institute of Ismaili Studies and I.B. Tauris. 1997.

- Donald Malcolm Reid (2009). "Al-Azhar". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195305135.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-530513-5.

- Mutahhari, Murtaza (2011-08-22). Training and Education in Islam. Islamic College for Advanced Studie. p. 5. ISBN 978-1904063445.

- Fathi, Malkawi; Abdul-Fattah, Hussein (1990). The Education Conference Book: Planning, Implementation Recommendations and Abstracts of Presented Papers. International Institute of Islamic Thought (IIIT). ISBN 978-1565644892.

- Edwards, Viv; Corson, David (1997). Encyclopedia of Language and Education. Kluwer Academic publication. ISBN 978-1565644892.

- "Education". oxfordislamicstudies.

- "Key findings on how world religions differ by education". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- "Muslim educational attainment around the world". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 2016-12-13. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- "Economics may limit Muslim women's education more than religion". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- "The Muslim gender gap in education is shrinking". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2019-11-10.