Balinese people

The Balinese people (Indonesian: Suku Bali) are an Austronesian ethnic group and nation native to the Indonesian island of Bali. The Balinese population of 4.2 million (1.7% of Indonesia's population) live mostly on the island of Bali, making up 89% of the island's population.[3] There are also significant populations on the island of Lombok and in the easternmost regions of Java (e.g. the regency of Banyuwangi).

A Balinese couple during their wedding with their friends. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3,946,416 (2010 census)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 3,946,416[2] | |

| | 3,336,065 |

| | 119,407 |

| | 115,812 |

| | 104,810 |

| | 49,411 |

| | 38,552 |

| | 27,330 |

| 5,700 | |

| 5,529 | |

| 200 | |

| Languages | |

| Balinese language, Sasak language, Indonesian language | |

| Religion | |

| Balinese Hinduism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Javanese, Bali Aga, Sasak, Tenggerese, Polynesians, and Austronesians | |

Origins

The Balinese originated from three periods of migration. The first waves of immigrants came from Java and Kalimantan in prehistoric times and were of proto-Malay stock.[4] The second wave of Balinese came slowly over the years from Java during the Hindu period. The third and final wave came from Java, between the 15th and 16th centuries, about the same time as the conversion to Islam in Java, causing aristocrats and peasants to flee to Bali after the collapse of the Javanese Hindu Majapahit Empire in order to escape Mataram's Islamic conversion. This in turn reshaped the Balinese culture into a syncretic form of classical Javanese culture mixed with many Balinese elements.[5]

A DNA study in 2005 by Karafet et al., found that 12% of Balinese Y-chromosomes are of likely Indian origin, while 84% are of likely Austronesian origin, and 2% of likely Melanesian origin.[6]

Culture

Balinese culture is a mix of Balinese Hindu-Buddhist religion and Balinese customs. It is perhaps most known for its dance, drama and sculpture. The island is also known for its Wayang kulit or Shadow play theatre. Even in rural and neglected villages, beautiful temples are a common sight; and so are skillful gamelan players and talented actors.[7] Even layered pieces of palm leaf and neat fruit arrangements made as offerings by Balinese women have an artistic side to them.[8] According to Mexican art historian José Miguel Covarrubias, works of art made by amateur Balinese artists are regarded as a form of spiritual offering, and therefore these artists do not care about recognition of their works.[9] Balinese artists are also skilled in duplicating art works such as carvings that resemble Chinese deities or decorating vehicles based on what is seen in foreign magazines.[10]

The culture is noted for its use of the gamelan in music and in various traditional events of Balinese society. Each type of music is designated for a specific type of event. For example, music for a piodalan (birthday celebration) is different from music used for a metatah (teeth grinding) ceremony, just as it is for weddings, Ngaben (cremation of the dead ceremony), Melasti (purification ritual) and so forth.[11] The diverse types of gamelan are also specified according to the different types of dance in Bali. According to Walter Spies, the art of dancing is an integral part of Balinese life as well as an endless critical element in a series of ceremonies or for personal interests.[12]

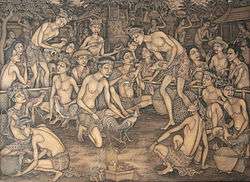

Traditionally, displaying female breasts is not considered immodest. Balinese women can often be seen with bared chests; however, a display of the thigh is considered immodest. In modern Bali these customs are normally not strictly observed, but visitors to Balinese temples are advised to cover their legs.

In the Balinese naming system, a person's rank of birth or caste is reflected in the name.[13]

Legong dance

Legong dance.jpg) Balinese gamelan

Balinese gamelan Balinese wood carver

Balinese wood carver Balinese painting

Balinese painting

Puputan

A puputan is an act of mass suicide through frontal assaults in battle, and was first noted by the Dutch during the colonization of Bali. The latest act of puputan was during the Indonesian war of Independence, with Lt. Colonel I Gusti Ngurah Rai as the leader in the battle of Margarana. The airport in Bali is named after him in commemoration.[14]

Religion

The vast majority of the Balinese believe in Agama Tirta, "holy-water religion". It is a Shivaite sect of Hinduism. Traveling Indian priests are said to have introduced the people to the sacred literature of Hinduism and Buddhism centuries ago. The people accepted it and combined it with their own pre-Hindu mythologies.[15] The Balinese from before the third wave of immigration, known as the Bali Aga, are mostly not followers of Agama Tirta, but retain their own animist traditions.

Festivals

Balinese people celebrate multiple festivals, including the Kuta Carnival, the Sanur Village Festival, and the Bali Kite Festival,[16] where participants fly fish-, bird-, and leaf-shaped kites while an orchestra plays traditional music.

See also

References

- Na'im, Akhsan; Syaputra, Hendry (2010). "Nationality, Ethnicity, Religion, and Languages of Indonesians" (PDF) (in Indonesian). Statistics Indonesia (BPS). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- Akhsan Na'im, Hendry Syaputra (2011). Kewarganegaraan, Suku Bangsa, Agama dan Bahasa Sehari-hari Penduduk Indonesia Hasil Sensus Penduduk 2010. Badan Pusat Statistik. ISBN 978-979-064-417-5.

- Bali faces population boom, now home to 4.2 million residents

- Shiv Shanker Tiwary & P.S. Choudhary (2009). Encyclopaedia Of Southeast Asia And Its Tribes (Set Of 3 Vols.). Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-261-3837-1.

- Andy Barski, Albert Beaucort and Bruce Carpenter (2007). Bali and Lombok. Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-0-7566-2878-9.

- Karafet, Tatiana M.; Lansing, J S.; Redd, Alan J.; and Reznikova, Svetlana (2005) "Balinese Y-Chromosome Perspective on the Peopling of Indonesia: Genetic Contributions from Pre-Neolithic Hunter- Gatherers, Austronesian Farmers, and Indian Traders," Human Biology: Vol. 77: Iss. 1, Article 8. Available at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol/vol77/iss1/8

- Adrian Vickers (2012). Bali Tempo Doeloe. Komunitas Bambu. p. 293. ISBN 978-602-9402-07-0.

- Adrian Vickers (2012). Bali Tempo Doeloe. Komunitas Bambu. p. 294. ISBN 978-602-9402-07-0.

- Adrian Vickers (2012). Bali Tempo Doeloe. Komunitas Bambu. p. 296. ISBN 978-602-9402-07-0.

- Adrian Vickers (2012). Bali Tempo Doeloe. Komunitas Bambu. p. 298. ISBN 978-602-9402-07-0.

- Beryl De Zoete, Arthur Waley & Walter Spies (1938). Dance and Drama in Bali. Faber and Faber. p. 298. OCLC 459249128.

- Beryl De Zoete, Arthur Waley & Walter Spies (1938). Dance and Drama in Bali. Faber and Faber. pp. 6–10. OCLC 459249128.

- Leo Howe (2001). Hinduism & Hierarchy In Bali. James Currey. p. 46. ISBN 1-930618-09-3.

- Helen Creese, I Nyoman Darma Putra & Henk Schulte Nordholt (2006). Seabad Puputan Badung: Perspektif Belanda Dan Bali. KITLV-Jakarta. ISBN 979-3790-12-1.

- J. Stephen Lansing (1983). The Three Worlds of Bali. Praeger. ISBN 978-0-03-063816-9.

- Tempo: Indonesia's Weekly News Magazine, Volume 7, Issues 9-16. Arsa Raya Perdana. 2006. p. 66.