Islam in Indonesia

Islam is the largest religion in Indonesia with most adherents, with 87.2% of Indonesian population identifying themselves as Muslim in a 2010 survey.[1][2] Indonesia has the largest Muslim population in the world, with approximately 225 million Muslims.

In terms of denomination, the overwhelming majority (99%) adheres to Sunni Islam, while there are around one million Shias (0.5%), who are concentrated around Jakarta,[3] and about 400,000 Ahmadi Muslims (0.2%).[4] In terms of Islamic schools of jurisprudence, based on demographic statistics, 99% of Indonesian Muslims mainly follow the Shafi'i school,[5][6] although when asked, 56% does not adhere to any specific school.[7] Trends of thought within Islam in Indonesia can be broadly categorized into two orientations; "modernism" which closely adheres to orthodox theology while embracing modern learning, and "traditionalism" which tends to follow the interpretations of local religious leaders and religious teachers at Islamic boarding schools (pesantren). There is also a historically important presence of a syncretic form of Islam known as kebatinan.

Islam in Indonesia is considered to have gradually spread through merchant activities by Arab Muslim traders, adoption by local rulers and the influence of mysticism since the 13th century.[8][9][10] During the late colonial era, it was adopted as a rallying banner against colonialism.[11] Today, although Indonesia has an overwhelming Muslim majority, it is not an Islamic state, but constitutionally a secular state whose government officially recognizes six formal religions.[lower-alpha 1]

Distribution

Muslims constitute a majority in most regions of Java, Sumatra, West Nusa Tenggara, Sulawesi, coastal areas of Kalimantan, and North Maluku. Muslims form distinct minorities in Papua, Bali, East Nusa Tenggara, parts of North Sumatra, most inland areas of Kalimantan, and North Sulawesi. Together, these non-Muslim areas originally constituted more than one third of Indonesia prior to the massive transmigration effort sponsored by the Suharto government and recent spontaneous internal migration.

Internal migration has altered the demographic makeup of the country over the past three decades. It has increased the percentage of Muslims in formerly predominantly Christian eastern parts of the country. By the early 1990s, Christians became a minority for the first time in some areas of the Maluku Islands. While government-sponsored transmigration from heavily populated Java and Madura to less populated areas contributed to the increase in the Muslim population in the resettlement areas, no evidence suggests that the government intended to create a Muslim majority in Christian areas, and most Muslim migration seemed spontaneous. Regardless of its intent, the economic and political consequences of the transmigration policy contributed to religious conflicts in Maluku, Central Sulawesi, and to a lesser extent in Papua.

Islam in Indonesia by region

Percentage of Muslims in Indonesia by region:

| Region | Percentage Of Muslims | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Aceh | 98.19 | Source |

| Bali | 13.37 | Source |

| Bangka Belitung Islands | 89.00 | Source |

| Banten | 91.64 | Source |

| Bengkulu | 97.29 | Source |

| Central Java | 96.74 | Source |

| Central Kalimantan | 74.31 | Source |

| Central Sulawesi | 77.72 | Source |

| East Java | 96.36 | Source |

| East Kalimantan | 85.38 | Source |

| East Nusa Tenggara | 5.05 | Source |

| Gorontalo | 96.66 | Source |

| Jakarta | 83.43 | Source |

| Jambi | 95.41 | Source |

| Lampung | 95.48 | Source |

| Maluku | 49.61 | Source |

| North Kalimantan | 65.75 | Source |

| North Maluku | 74.28 | Source |

| North Sulawesi | 30.90 | Source |

| North Sumatra | 60.39 | Source |

| Papua | 15.88 | Source |

| Riau | 87.98 | Source |

| Riau Islands | 77.51 | Source |

| South Kalimantan | 96.67 | Source |

| South Sulawesi | 89.62 | Source |

| South Sumatra | 96.00 | Source |

| Southeast Sulawesi | 95.23 | Source |

| West Java | 97.00 | Source |

| West Kalimantan | 59.22 | Source |

| West Nusa Tenggara | 96.47 | Source |

| West Papua | 38.40 | Source |

| West Sulawesi | 82.66 | Source |

| West Sumatra | 98.00 | Source |

| Yogyakarta | 91.94 | Source |

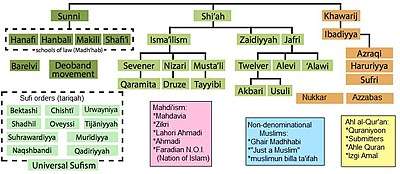

Branches

The Islamic schools and branches in Indonesia reflects the activity of Islamic doctrines and organizations operating in Indonesia. In terms of denomination, Indonesia is a majority Sunni country with minority of other sects such as Shia Islam and Ahmadiyya. In terms of Islamic schools of jursiprudence, Shafi'i school is dominant in Indonesia at large.[5] Proliferation of Shafi’i school is considered owing to the Arab merchants from the southern Arabian Peninsula following this school of jurisprudence.[14][15]

Division of Islam in Indonesia

Classical documentations divide Indonesian Muslims between "nominal" Muslims, or abangan, whose lifestyles are more oriented toward non-Islamic cultures, and "orthodox" Muslims, or santri, who adhere to the orthodox Islamic norms. Abangan was considered an indigenous blend of native and Hindu-Buddhist beliefs with Islamic practices sometimes also called Javanism, kejawen, agama Jawa, or kebatinan.[16] On Java, santri was not only referred to a person who was consciously and exclusively Muslim, but it also described persons who had removed themselves from the secular world to concentrate on devotional activities in Islamic schools called pesantren—literally "the place of the santri". The terms and precise nature of this differentiation were in dispute throughout the history, and today it is considered obsolete.[17]

In contemporary era, often the distinction is made between "traditionalism" and "modernism". Traditionalism, exemplified by the civil society organization Nahdlatul Ulama, is known as an ardent advocate of Islam Nusantara; a distinctive brand of Islam that has undergone interaction, contextualization, indigenization, interpretation and vernacularization in line with socio-cultural conditions in Indonesia.[18] Islam Nusantara promotes moderation, compassion, anti-radicalism, inclusiveness and tolerance.[19] On the other spectrum is modernism which is inspired heavily by Islamic Modernism, and the civil society organization Muhammadiyah is known as the ardent proponent.[20] Modernist Muslims advocate the reform of Islam in Indonesia, which is perceived as having deviated from the historical Islamic orthodoxy. They emphasize the authority of the Qur'an and the Hadiths, and oppose syncretism and taqlid to the ulema. This division however, also has been considered oversimplification in recent analysis.[17]

Kebatinan

There are also various other forms and adaptations of Islam influenced by local cultures which hold different norms and perceptions throughout the archipelago.[17] The principal example is a syncretic form of Islam known as kebatinan, which is an amalgam of animism, Hindu-Buddhist, and Islamic — especially Sufi — beliefs. This loosely organised current of thought and practice was legitimised in the 1945 constitution and, in 1973, when it was recognised as Kepercayaan kepada Tuhan Yang Maha Esa (Indonesian: Believer of One Supreme God) that somewhat gained the status as one of the agama, President Suharto counted himself as one of its adherents. The Kebatinan or Kepercayaan have no certain prophet, sacred book, nor distinct religious festivals and rituals; it has more to do with each adherent's internalised transcendental vision and beliefs in their relations with the supreme being. As the result there is an inclusiveness that the kebatinan believer could identify themselves with one of six officially recognised religions, at least in their identity card, and still maintain their kebatinan belief and way of life. Kebatinan is generally characterised as mystical, and some varieties were concerned with spiritual self-control. Although there were many varieties circulating in 1992, kebatinan often implies pantheistic worship because it encourages sacrifices and devotions to local and ancestral spirits. These spirits are believed to inhabit natural objects, human beings, artefacts, and grave sites of important wali (Muslim saints). Illness and other misfortunes are traced to such spirits, and if sacrifices or pilgrimages fail to placate angry deities, the advice of a dukun or healer is sought. Kebatinan, while it connotes a turning away from the militant universalism of orthodox Islam, moves toward a more internalised universalism. In this way, kebatinan moves toward eliminating the distinction between the universal and the local, the communal and the individual.

Other branches

More recent currents of Islamic thoughts that taken roots include Islamism. Today, the leading Islamic political party in Indonesia is Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) which is known for serving as a regional wing of Muslim Brotherhood movement in Indonesia.[21]:34 Salafism, an Islamic branch calling to understand the Qur'an and the Sunnah according to the first generations of Muslims, and to avoid later introduced matters in the religion, have seen expansion within Indonesian society especially since the 1990s.[22]

A small minority subscribe to the Shia Islam and Ahmadiyya. There are around one million Shia Muslims, or 0.5% of country's population, who are concentrated around Jakarta.[3] Historical Shia community is considered a descendant of the minority segment of Hadhrami immigrants, and it was spread from Aceh where originally a center of Shia Islam in Indonesia.[23] In the contemporary era, interests toward Shia Islam grew after the Iranian Islamic Revolution, since which a number of Shia publications were translated into Indonesian.[17] Another minority Islamic sect is Ahmadiyya. The Association of Religion Data Archives estimates that there are around 400,000 Ahmadi Muslims in Indonesia,[24] spread over 542 branches across the country. Ahmadiyya history in Indonesia began since the missionary activity during the 1920s, established the movement in Tapaktuan, Aceh.[25] Both Shia and Ahmadi Muslims have been facing increasing intolerance and persecutions by reactionary and radical Islamic groups.[26][27]

Organisations

In Indonesia, civil society organizations have historically held distinct and significant weight within the Muslim society, and these various institutions have contributed greatly in the both intellectual discourse and public sphere for the culmination of new thoughts and sources for communal movements.[28]:18–19 75% of 200 million Indonesian Muslims identify either as Nahdlatul Ulama or Muhammadiyah, making these organizations a 'steel frame' of Indonesian civil society.[29]

Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), the largest traditionalist organisation, focuses on many of the activities such as social, religious and education and indirectly operates a majority of the country's Islamic boarding schools. Claiming 40 to 60 million followers, NU is the country's largest organisation and perhaps the world's largest Islamic group.[29][30][31] Founded in 1926, NU has a nationwide presence but remains strongest in rural Java. It follows the ideology of Ahle Sunnah wal Jamaah with Sufism of Imam Ghazali and Junaid Bagdadi. Many NU followers give great deference to the views, interpretations, and instructions of senior NU religious figures, alternately called "Kyais" or "Ulama." The organisation has long advocated religious moderation and communal harmony. On the political level, NU, the progressive Consultative Council of Indonesian Muslims (Masyumi), and two other parties were forcibly streamlined into a single Islamic political party in 1973 — the United Development Party (PPP). Such cleavages may have weakened NU as an organised political entity, as demonstrated by the withdrawal of the NU from active political competition, but as a popular religious force NU showed signs of good health and a capacity to frame national debates.

The leading national modernist social organisation, Muhammadiyah, has branches throughout the country and approximately 29 million followers.[32] Founded in 1912, Muhammadiyah runs mosques, prayer houses, clinics, orphanages, poorhouses, schools, public libraries, and universities. On 9 February, Muhammadiyah's central board and provincial chiefs agreed to endorse the presidential campaign of a former Muhammadiyah chairman. This marked the organisation's first formal foray into partisan politics and generated controversy among members.

A number of smaller Islamic organisations cover a broad range of Islamic doctrinal orientations. At one end of the ideological spectrum lies the controversial Islam Liberal Network (JIL), which aims to promote a pluralist and more liberal interpretation of Islamic thinking.

Equally controversial are groups at the other end of this spectrum such as Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia (HTI), which advocates a pan-Islamic caliphate and the full implementation of shari'a,[33] the Indonesian Mujahedeen Council (MMI), which advocates implementation of shari'a as a precursor to an Islamic state, and the sometimes violent Islamic Defenders Front (FPI). Countless other small organisations fall between these poles. Another small organisation, the Indonesian Islamic Propagation Institute (LDII) continues to grow.[34]

History

Spread of Islam (1200–1600)

There are evidence of Arab Muslim traders entering Indonesia as early as the 8th century.[11][17] However, it was not until the end of the 13th century that the spread of Islam began.[11] At first, Islam was introduced through Arab Muslim traders, and then the missionary activity by scholars, and it was further aided by the adoption by the local rulers and the conversion of the elites.[17] The missionaries had originated from several countries and regions, initially from the South Asia such as Gujarat and other Southeast Asia such as Champa,[35] and later from the southern Arabian Peninsula such as the Hadhramaut.[17]

In the 13th century, Islamic polities began to emerge on the northern coast of Sumatra. Marco Polo, on his way home from China in 1292, reported at least one Muslim town.[36] The first evidence of a Muslim dynasty is the gravestone, dated AH 696 (AD 1297), of Sultan Malik al Saleh, the first Muslim ruler of Samudera Pasai Sultanate. By the end of the 13th century, Islam had been established in Northern Sumatra.

In general, local traders and the royalty of major kingdoms were the first to adopt the new religion. The spread of Islam among the ruling class was precipitated as Muslim traders married the local women, with some of the wealthier traders marrying into the families of the ruling elite.[8] Indonesian people as local rulers and royalty began to adopt it, and subsequently, their subjects mirrored their conversion. Although the spread was slow and gradual,[37] the limited evidence suggests that it accelerated in the 15th century, as the military power of Malacca Sultanate in the Malay Peninsula and other Islamic Sultanates dominated the region aided by episodes of Muslim coup such as in 1446, wars and superior control of maritime trading and ultimate markets.[37][38]

By the 14th century, Islam had been established in northeast Malaya, Brunei, the southwestern Philippines and among some courts of coastal East and Central Java; and the 15th in Malacca and other areas of the Malay Peninsula.[39] The 15th century saw the decline of Hindu Javanese Majapahit Empire, as Muslim traders from Arabia, India, Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula, and also China began to dominate the regional trade that once controlled by Javanese Majapahit traders. Chinese Ming dynasty provided systematic support to Malacca. Ming Chinese Zheng He's voyages (1405 to 1433) is credited for creating Chinese Muslim settlement in Palembang and north coast of Java.[40] Malacca actively encouraged the conversion to Islam in the region, while Ming fleet actively established Chinese-Malay Muslim community in northern coastal Java, thus created a permanent opposition to the Hindus of Java. By 1430, the expeditions had established Muslim Chinese, Arab and Malay communities in northern ports of Java such as Semarang, Demak, Tuban, and Ampel; thus Islam began to gain a foothold on the northern coast of Java. Malacca prospered under Chinese Ming protection, while the Majapahit were steadily pushed back.[41] Dominant Muslim kingdoms during this time included Samudera Pasai in northern Sumatra, Malacca Sultanate in eastern Sumatra, Demak Sultanate in central Java, Gowa Sultanate in southern Sulawesi, and the sultanates of Ternate and Tidore in the Maluku Islands to the east.

Indonesia's historical inhabitants were animists, Hindus, and Buddhists.[42] Through assimilation related to trade, royal conversion, and conquest, however, Islam had supplanted Hinduism and Buddhism as the dominant religion of Java and Sumatra by the end of the 16th century. During this process, "cultural influences from the Hindu-Buddhist era were mostly tolerated or incorporated into Islamic rituals."[11] Islam didn't obliterate the preexisting culture; rather, it incorporated and embedded the local customs and non-Islamic elements among rules and arts, and reframed them as the Islamic traditions.[17]

In part, the strong presence of Sufism has been considered a major enabler of this syncretism between Islam and other religions. Sufism retained strong influence especially among the Islamic scholars arrived during the early days of the spread of Islam in Indonesia, and many Sufi orders such as Naqshbandiyah and Qadiriyya have attracted newly Indonesian converts, proceeded to branch into different local divisions. Sufi mysticism which had proliferated during this course had shaped the syncretic, eclectic and pluralist nature of Islam in Indonesian during the time.[17] Prolific Sufis from the Indonesian archipelago were already known in Arabic sources as far back as the 13th Century.[43] One of the most important Indonesian Sufis from this time is Hamzah Fansuri, a poet, and writer from the 16th century.[28]:4 The preeminence of Sufism among Islam in Indonesian continued until the shift of external influence from the South Asia to the Arabian Peninsula, whose scholars brought more orthodox teachings and perceptions of Islam.[17]

The gradual adoption of Islam by Indonesians was perceived as a threat by some ruling powers. As port towns adopted Islam, it undermined the waning power of the east Javanese Hindu/Buddhist Majapahit kingdom in the 16th century. Javanese rulers eventually fled to Bali, where over 2.5 million Indonesians practiced their version of Hinduism. Unlike coastal Sumatra, where Islam was adopted by elites and masses alike, partly as a way to counter the economic and political power of the Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms, in the interior of Java the elites only gradually accepted Islam, and then only as a formal legal and religious context for Javanese spiritual culture. The eastern islands remained animist largely until adopting Islam and Christianity in the 17th and 18th centuries, whereas Bali still retains a Hindu majority.[44] By the late 15th century, the Majapahit Empire in Java had begun its decline. This last Hindu kingdom in Java fell under the rising power of the Islamized Sultanate of Demak in the 1520s; in 1527, the Muslim ruler renamed newly conquered Sunda Kelapa as Jayakarta meaning "precious victory" which was eventually contracted to Jakarta. Islam in Java then began to spread formally, building on the spiritual influences of the revered Sufi saints Wali Songo (or Nine Saints).

Despite being one of the most significant developments in Indonesian history, historical evidence is fragmentary and uninformative such that understandings of the coming of Islam to Indonesia are limited; there is considerable debate amongst scholars about what conclusions can be drawn about the conversion of Indonesian peoples.[45] The primary evidence, at least of the earlier stages of the process, are gravestones and a few travelers' accounts, but these can only show that indigenous Muslims were in a certain place at a certain time. This evidence is not sufficient to comprehensively explain more complicated matters such as how lifestyles were affected by the new religion or how deeply it affected societies.

Early modern period (1600–1945)

The Dutch entered the region in the 17th century due to its lucrative wealth established through the region's natural resources and trade.[46][lower-alpha 2] The entering of the Dutch resulted in a monopoly of the central trading ports. However, this helped the spread of Islam, as local Muslim traders relocated to the smaller and remoter ports, establishing Islam into the rural provinces.[46] Towards the beginning of the 20th century "Islam became a rallying banner to resist colonialism."[11]

During this time the introduction of steam-powered transportation and printing technology was facilitated by European expansion. As a result, the interaction between Indonesia and the rest of the Islamic world, in particular the Middle East, had significantly increased.[28]:2 In Mecca, the number of pilgrims grew exponentially to the point that Indonesians were markedly referred as "rice of the Hejaz." The exchange of scholars and students was also increased. Around two hundred Southeast Asian students, mostly Indonesian, were studying in Cairo during the mid-1920s, and around two thousand citizens of Saudi Arabia were Indonesian origin. Those who returned from the Middle East had become the backbone of religious training in pesantrens.[17]

Concurrently, numbers of newly founded religious thoughts and movements in the Islamic world had inspired the Islamic current in Indonesia as well. In particular, Islamic Modernism was inspired by the Islamic scholar Muhammad 'Abduh to return to the original scripture of the religion. The Modernist movement in Indonesia had criticized the syncretic nature of Islam in Indonesia and advocated for the reformism of Islam and the elimination of perceived un-Islamic elements within the traditions. The movement also aspired for incorporating the modernity into Islam, and for instance, they "built schools that combined an Islamic and secular curriculum" and was unique in that it trained women as preachers for women.[11] Through the activities of the reformers and the reactions of their opponents, Indonesian society became more firmly structured along communal (aliran) rather than class lines.[47]

Reformist movements had especially taken roots in the Minangkabau area of West Sumatra, where its ulema played an important role in the early reform movement.[48]:353 Renowned Minangkabau imam in Mecca, Ahmad Khatib al-Minangkabawi had contributed greatly to the reformist training. He was singlehandedly responsible for educating many of the essential Muslim figures during this time.[49] In 1906, Tahir bin Jalaluddin, a disciple of al-Minangkabawi, published al-Iman, the Malay newspaper in Singapore. Five years later followed publication of Al-Munir magazine by Abdullah Ahmad in Padang.[50] In the first 20th century, Muslim modernist school arose in West Sumatra, such as Adabiah (1909), Diniyah Putri (1911), and Sumatera Thawalib (1915). The movement had also attained its supporter base in Java. In Surakarta, leftist Muslim Haji Misbach published the monthly paper Medan Moeslimin and the periodical Islam Bergerak.[28] In Jogjakarta, Ahmad Dahlan, also a disciple of al-Minangkabawi, established Muhammadiyah in 1911, spearheading the creation of Islamic mass organization. Muhammadiyah rapidly expanded its influence across the archipelago, with Abdul Karim Amrullah establishing the West Sumatra chapter in 1925 for instance. Other modernist organizations include Al-Irshad Al-Islamiya (1914) and PERSIS (1923). Soon after, traditionalist Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) was founded in 1926 by Hasyim Asy'ari, another disciple of al-Minangkabawi, in response to the perceived growing threat of reformist waves.[48]:356 Other traditionalist organizations included the Islamic Education Association (Perti) (1930)[51] and Lombok-based Nahdlatul Wathan (1953).

A combination of reformist thoughts and the growing sense of sovereignty had led to the brief development of Islam as a vehicle for the political struggle against the Dutch colonialism. The earliest example is Padri movement from Minangkabau. Padri movement was inspired by Wahhabism during its inception, and aimed at purification of Islam in Indonesia reciprocally. The movement eventually turned into a struggle against Dutch colonialism during the Padri War (1803–1837).[52] One of the leaders, Tuanku Imam Bonjol, is declared a National Hero of Indonesia.[53][54] In the early 20th century, Sarekat Islam was developed as the first mass nationalist organization against colonialism.[55] Sarekat Islam championed Islam as a common identity among vast and diverse ethnic and cultural compositions throughout the archipelago, especially against the perceived enemy of the Christian masters. The educational institutions such as Jamiat Kheir also supported the development. In the process, Islam gave the sense of identity which contributed to the cultivation of Indonesian nationalism. Under this circumstance, early Indonesian nationalists were eager to reflect themselves as a part of the ummah (worldwide Islamic community). They also had interests in Islamic issues such as re-establishment of Caliphate and the movements such as pan-Islamism. For these reasons, Dutch colonial administration saw Islam as a potential threat and treated the returning pilgrims and students from the Middle East with particular suspicion.[17] Similar Islamic-nationalist organization Union of Indonesian Muslims (PERMI) faced severe crackdown by the Dutch colonial government, leading to the arrest of its members including Rasuna Said.[56]

Islam as a vehicle of Indonesian nationalism, however, had gradually waned in the face of the emergence of secular nationalism and more radical political thoughts such as communism. The inner struggle among Sarekat Islam between the reformists and the traditionalists had also contributed to its decline. This had created a vacuum within the Muslim community for the leadership role, which filled by civil society organizations such as Muhammadiyah, NU, more puritanical PERSIS and Al-Irshad Al-Islamiya. These organizations upheld non-political position and concentrated on the social reforms and proselytization. This trend persisted during the Japanese occupation as well, whose occupational administration took the ambivalent stance toward Islam. Islam was considered both as a potential friend against the Western imperialism and a potential foe against their vision of Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.[17]

Post-independence (since 1945)

When Indonesia declared independence in 1945, it became the second largest Muslim-majority state in the world. Following the separation of Bangladesh from Pakistan in 1971, it emerged as the most populous country with the Muslim majority in the world. Post-independence had seen the greatest upheaval of the Muslim society on various aspects of society. This owes to the independence, increased literacy and educational attainment of Muslims, funding from the Middle East and all the more accelerated exchange between other Muslim countries.[17]

Subsequent development of the Muslim society had brought Indonesia even closer to the center of Islamic intellectual activity. Numbers of scholars and writers have contributed to the development of Islamic interpretations within the Indonesian context, often through the intellectual exchange between the foreign contemporaries.[17] Abdul Malik Karim Amrullah (Hamka) was a modernist writer and religious leader who is credited for Tafsir al-Azhar. It was the first comprehensive Qur'anic exegesis (tafsir) written in the Indonesian, which attempted at construing Islamic principles within the Malay-Minangkabau culture.[57] Harun Nasution was a pioneering scholar adhered to the humanist and rationalist perspectives in Indonesian intellectual landscape, advocating for a position described as neo-Mutazilite.[58] Nurcholish Madjid (Cak Nur) was a highly influential scholar who is credited for cultivating the modernist and reformist discourse, influenced largely by Pakistani Islamic philosopher Fazlur Rahman. Abdurrahman Wahid (Gus Dur), later president of Indonesia, went through the Islamic education at the University of Baghdad, and later became the central figure of the liberal Islamic trend in Indonesia.[59] Quraish Shihab compiled Tafsir Al-Mishbah which is considered a standard of Indonesian Islamic interpretation among mainstream Indonesian Islamic intellectuals.[60]

Post-independence had also seen an expansion in the activity of Islamic organizations, especially regarding missionary activities (dawah) and Islamization of lifestyles. The Ministry of Religion reported that as late as the 1960s, only minority of Muslims were practicing daily prayers and almsgiving. This status had drastically changed through the course of endeavor by the organizations such as Indonesian Islamic Dawah Council (DDII) led by Mohammad Natsir, not to mention aforementioned Muhammadiyah, NU, and PERSIS.[17] Among Islamic clergy, Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) has been operating as an authority regarding the legislative and juridical issues of Islam, and responsible for guiding the general direction of Islamic life in Indonesia, primarily through the issuance of fatwa.[61] More recently, organizations such as DDII and LIPIA have been acting as instruments of the propagation of Salafism or Wahhabism with funding from Saudi Arabia and other Gulf monarchies,[62][63][64] that “has contributed to a more conservative, more intolerant atmosphere”[65] and eager to strip heritages of traditional Indonesian Islam of local customs containing elements of Hindu ritual and Sufi mysticism.[66] On the political arena, the coalition of Muhammadiyah and NU have established the Masyumi Party, which served as a mainstream Islamic political party until its dissolution in 1960. Meanwhile, militant Islamic organizations such as Darul Islam, Laskar Jihad, and Jemaah Islamiyah had also seen its growth, aided mostly by the foreign funding as well.[17]

Upon independence, there was significant controversy surrounding the role of Islam in politics, and this had caused enormous tensions. The contentions were mainly surrounding the position of Islam in the constitution of Indonesia. Islamic groups have aspired for the supreme status of Islam within the constitutional framework by the inclusion of the Jakarta Charter which obliges Muslim to abide by shari'a. This was denied by the Sukarno regime with the implementation of the more pluralist constitution heeding to the ideology of Pancasila, which deemed as non-Islamic.[17] Eventually, "Indonesia adopted a civil code instead of an Islamic one."[46] However, the struggle for the constitutional amendment continued. The hostility against the Sukarno regime was manifested on various other occasions. Most notably the anti-communist genocide perpetuated actively by Ansor Youth Movement, the youth wing of NU (which was initially supportive of the Sukarno regime) and other Islamic groups.[67] Muslims adhering to the syncretic form of Islam known as Abangan had also become the target of this mass killing.[68] Communism was considered hostile by Muslims due to perceived atheistic nature and the tendency of landowners being local Islamic chiefs.[17]

In the New Order years (the Suharto regime), there was an intensification of religious belief among Muslims.[69] The Suharto regime, initially hoped as the ally of Islamic groups, quickly became the antagonist following its attempt at reformation of educational and marital legislation to more secular-oriented code. This met strong opposition, with marriage law left as Islamic code as a result. Suharto had also attempted at consolidating Pancasila as the only state ideology, which was also turned down by the fierce resistance of Islamic groups.[17] Under the Suharto regime, containment of Islam as a political ideology had led to all the Islamic parties forcibly unite under one government-supervised Islamic party, the United Development Party (PPP).[11] Certain Islamic organizations were incorporated by the Suharto regime, most notably MUI, DDII, and Indonesian Association of Muslim Intellectuals (ICMI) in order to absorb the political Islam for the regime's gain.[70] With Suharto's resignation in 1998, "the structure that repressed religion and society collapsed."[11]

During the beginning of the Reformasi (reformation) era, the ascendance of Islamic political parties had led to the election of Abdurrahman Wahid, the leader of NU, as the fourth president of Indonesia, and the appointment of Amien Rais, the leader of Muhammadiyah, as the chairman of the People's Consultative Assembly. This era was briefly marked by the collapse of social order, erosion of central administrative control and the breakdown of law enforcement. They resulted in violent conflicts in which Islamic groups were involved, including separatism of Aceh where more conservative form of Islam is favored, and sectarian clashes between Muslims and Christians in Maluku and Poso. With the collapse of the establishment, MUI began distancing themselves from the government and attempted to exercise wider influence toward the Islamic civil society in Indonesia. This led to the issuance of controversial 2005 fatwa condemning the notion of liberalism, secularism and pluralism,[70] and subsequent criticism by progressive intellectuals.[71] Political transition from the authoritarianism to democracy, however, went relatively smoothly owing considerably to the commitment of tolerance by the mass organizations such as NU and Muhammadiyah. This made Muslim civil society a key part of Indonesia's democratic transition.[72][73]

Currently, Muslims are considered fully represented in the democratically elected parliament.[11] There are numbers of active Islamic political parties, namely Muhammadiyah-oriented National Mandate Party (PAN),[74] NU-oriented National Awakening Party (PKB),[75] and Islamist Prosperous Justice Party (PKS).[21] The democratization had resulted in diversification of religious influence as well,[21] with the relative decline in influence of established institutions such as NU and Muhammadiyah,[76] and rise of smaller scale organizations and individual preachers such as Abdullah Gymnastiar (Aa Gym) and Yusuf Mansur. During the early 2000s, the returning of Abu Bakar Bashir who was in exile during the Suharto era as a spiritual leader of Jihadism in Indonesia resulted in the series of bombing attacks,[lower-alpha 3] which have been largely contained recently.[77] Contemporary Islam in Indonesia is analyzed in various ways, with certain analysis consider it as becoming more conservative,[21][lower-alpha 4] while others deem it as "too big to fail" for the radicalization.[78][79] Conservative development has seen the emergence of vigilante group Islamic Defenders Front (FPI),[80] persecution against Ahmadiyya exemplified by MUI's fatwa,[21] and the nationwide protest in 2016 against the incumbent governor of Jakarta Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok) accused of blasphemy.[81] Liberal development has seen the emergence of groups such as Liberal Islamic Network (JIL), formation of Islam Nusantara as a collective identity of pluralist Islam,[82] and the declining support for the Islamist political parties.[83]

Culture

Arts

Several artistic traditions in Indonesia, many of which existed since the pre-Islamic era, have absorbed Islamic influence and evolved in the form of artistic expression and attachment of religious implications.

Batik

Indonesian dyeing art of Batik has incorporated Islamic influence, through the inclusion of motifs and designs revering the Islamic artistic traditions such as Islamic calligraphy and Islamic interlace patterns, and the religious codes prescribing the avoidance of the depictions of human images. Islamic influence of batik is especially pronounced in the batik tradition situated around the Javanese region of Cirebon which forms the part of coastal Javanese batik heritage, the Central Sumatran region of Jambi which had thriving trade relations with Javanese coastal cities, and the South Sumatran region of Bengkulu where the strong sense of Islamic identity was cultivated. Jambi batik influenced the formation of Malaysian batik tradition which also encompasses the Islamic characters such as the adoption of the plants, floral motifs and geometrical designs, and the avoidance of interpretation of human and animal images as idolatry.[84][85] Minangkabau batik tradition is known for batiak tanah liek (clay batik), which uses clay as a dye for the fabric, and embraces the animal and floral motifs.[86] Bengkulu batik tradition is known for batik besurek, which literary means "batik with letters" as they draw inspiration from Arabic calligraphy. Islamic batik tradition occasionally depicts Buraq as well, an Islamic mythical creature from the heavens which transported the Islamic prophet Muhammad from Mecca to Jerusalem and back during the Isra and Mi'raj.

Wayang

Indonesian performing art of Wayang has a variety known as Wayang sadat which has deployed Wayang for religious teachings of Islam.[87] There is also Wayang Menak which is derived from Javanese-Islamic literature Serat Menak which is a Javanese rendering of Malay Hikayat Amir Hamzah, which ultimately derived from Persian Hamzanama, tells the adventure of Amir Hamzah, the uncle of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.[88] In Lombok, vernacular Wayang Kulit is known as Wayang Sasak, which incorporates puppets similar to the Javanese ringgits and based on the adventures of Amir Hamzah as well.

When Islam began spreading in Indonesia, the display of God or gods in human form was prohibited, and thus this style of painting and shadow play was suppressed. King Raden Patah of Demak, Java, wanted to see the wayang in its traditional form but failed to obtain permission from Muslim religious leaders. Religious leaders attempted to skirt the Muslim prohibition by converting the wayang golek into wayang purwa made from leather and displayed only the shadow instead of the puppets themselves.

Dance

History of dance in Indonesia can be roughly divided into the Hindu-Buddhist period and Islamic period. During the Islamic period, the vernacular and dharmic dances continued to be popular and tolerated. Artists and performers were using the styles of Hindu-Buddhist era but incorporated stories with Islamic implications and more modest clothing that conformed to the Islamic teaching. This change is markedly seen in Tari Persembahan from Jambi, in which the dancers are still adorned with the intricate gold of the Hindu/Buddhist era but the clothing is more modest. Newer styles of dance were introduced in the Islamic period, including Zapin dances of the Malay people and Gayonese Saman dance in Aceh, which adopted dance styles and music typical of Arab and Persia, and combined them with indigenous styles to form a newer generation of dance in the era of Islam. Saman dance was initially performed during the Islamic missionary activity (dawah) or during the certain customary events such as the commemoration of the Islamic prophet Muhammad's birthday, and today more commonly performed during any official events. The adoption of Persian and Arab musical instruments, such as rebana, tambur, and gendang drums that has become the main instrument in Islamic dances, as well as the chant that often quotes Islamic chants.

Architecture

The architecture of Indonesia after the spread of Islam was prominently characterized by the religious structure with the combination of Islamic implications and Indonesian architectural traditions. Initial forms of the mosque, for example, were predominantly built in the vernacular Indonesian architectural style which employs Hindu, Buddhist or Chinese architectural elements, and notably didn't equip orthodox form of Islamic architectural elements such as dome and minaret. Vernacular style mosques in Java is distinguished by its tall timber multi-level roofs known as tajug, similar to the pagodas of Balinese Hindu temples and derived from Indian and Chinese architectural styles.[89] Another characteristic of Javanese style mosque is the usage of gamelan drum instrument bedug as a substitute of prayer call (adhan). Bedug is often installed in the roofed front porch attached to the building known as serambi. Bedug is commonly used for prayer call or the signal during Ramadan throughout the Javanese mosques up until today. Prominent examples of mosques with vernacular Javanese designs are Demak Mosque in Demak, built in 1474, and the Menara Kudus Mosque in Kudus, built in 1549,[90] whose minaret is thought to be the watchtower of an earlier Hindu temple. Vernacular style mosques in Minangkabau area is distinguished by its multi-layer roof made of fiber resembling Rumah Gadang, the Minangkabau residential building. Prominent examples of mosques with vernacular Minangkabau designs are Bingkudu Mosque,[91] founded in 1823 by the Padris, and Jami Mosque of Taluak, built in 1860. In West Sumatra, there is also a tradition of multi-purpose religious architecture known as surau which is often built in vernacular Minangkabau style as well, with three- or five-tiered roofs and woodcarvings engraved in the facade. Vernacular style mosques in Kalimantan is influenced by the Javanese counterparts, exemplified by the Banjar architecture which employs three- or five-tiered roof with the steep top roof, compared to the relatively low-angled roof of Javanese mosque, and the employment of stilts in some mosques, a separate roof on the mihrab. Prominent examples including Heritage Mosque of Banua Lawas and Jami Mosque of Datu Abulung, both in South Kalimantan.

It was only after the 19th century the mosques began incorporating more orthodox styles which were imported during the Dutch colonial era. Architectural style during this era is characterized by Indo-Islamic or Moorish Revival architectural elements, with onion-shaped dome and arched vault. Minaret was not introduced to full extent until the 19th century,[89] and its introduction was accompanied by the importation of architectural styles of Persian and Ottoman origin with the prominent usage of calligraphy and geometric patterns. During this time, many of the older mosques built in traditional style were renovated, and small domes were added to their square hipped roofs. Simultaneously, eclectic architecture integrating European and Chinese styles was introduced as well. Prominent examples of Indonesian Islamic architecture with foreign styles including Baiturrahman Grand Mosque in Banda Aceh, completed in 1881, designed in Indo-Saracenic Revival architecture, and Great Mosque of Palembang in Palembang, initially completed in 1798, and later expanded with integrating Chinese, Malay and European architectural styles harmonized together.

Clothing

The peci, songkok, or kopiah in Java,[92] is a velvet cap with generally black color worn by Muslim men. It is originated within the Malay culture and can be traced back to the Ottoman fez. It is worn during the formal occasions, including Islamic religious occasions such as Idul Fitr and Idul Adha, as well as congregational prayers when visiting mosques.[93]

The sarong is the popular garment worn mostly by Muslim men, notably in Java, Bali, Sumatra and Kalimantan. It is a large tube or length of fabric, often wrapped around the waist, and the fabric often has woven plaid or checkered patterns, or brightly colored by means of batik or ikat dyeing. Many modern sarongs have printed designs, often depicting animals or plants. It is mostly worn as a casual wear but often worn during the congregational prayers as well. The baju koko, also known as baju takwa, is a traditional Malay-Indonesian Muslim shirt for men, worn usually during the formal religious occasions, such as Idul Fitr festival or Friday prayers. It is often worn with the sarong and peci.

The kerudung is an Indonesian Muslim women's hijab, which is a loosely worn cloth over the head. Unlike completely covered counterpart of jilbab, parts of hairs and neck are still visible. The jilbab is a more conservative Muslim women's hijab, adopted from Middle Eastern style, and usually worn by more conservative Muslim women. Unlike kerudung, hair and neck are completely covered. Jilbab in Indonesian context means headscarf and does not designate the long overgarment as implied in the Muslim society in other countries.

Festival

Muslim holy days celebrated in Indonesia include the Isra and Mi'raj, Idul Fitr, Idul Adha, the Islamic New Year, and the Prophet's Birthday.

Hajj

The government has a monopoly on organising the hajj pilgrimage to Mecca, and in February 2010, following the latest Hajj, the Department of Religious Affairs drew sharp criticism for mismanaging the registration of approximately 30,000 prospective pilgrims after they had paid the required fees. The government unilaterally expanded the country's quota of 205,000 pilgrims, claiming it had informal approval from the Saudi Government, an assertion that proved incorrect. Members of the House of Representatives have sponsored a bill to set up an independent institution, thus ending the department's monopoly.

Tabuik

Tabuik is a Shia Islamic occasion in Minangkabau region, particularly in the city of Pariaman and it is a part of the Shia days of remembrance among the local community. Tabuik refers to the towering funeral biers carried during the commemoration. The event has been performed every year since the Day of Ashura in 1831, when the practice was introduced to the region by the Shia sepoy troops from India who were stationed—and later settled—there during the British Raj.[94] The festival enacts the Battle of Karbala and plays the tassa and dhol drums.

Society

Gender

To a significant degree, the striking variations in the practice and interpretation of Islam — in a much less austere form than that practiced in the Middle Eastern communities — reflect Indonesia's lifestyle.[95]

Indonesian Muslimah (female Muslims) do enjoy a significantly greater social, educational, and work-related freedom than their counterparts in countries such as Saudi Arabia or Iran. Thus, it is normal, socially acceptable, and safe for a female Muslim to go out, drive, work, or study in some mixed environments independently without any male relative chaperone. Women's higher employment rate is also an important difference between Indonesian and Middle Eastern cultures.

Gender segregation

Compared to their Middle Eastern counterparts, a majority of Muslims in Indonesia have a more relaxed view and a moderate outlook on social relations. Strict sex segregation is usually limited to religious settings, such as in mosques during prayer, and is not practiced in public spaces. In both public and Islamic schools, it is common for boys and girls to study together in their classroom. Some pesantren boarding schools, however, do practice sex segregation. Nevertheless, amid the recent advent of Wahabi and Salafi influences, a minority of Indonesian Muslims adhere to a more strict and orthodox vision which practices sex segregation in public places. This is done as far as avoiding contact between opposite sexes; for example, some women wearing hijab might refuse to shake hands or converse with men.

Politics

Although it has an overwhelming Muslim majority, the country is not an Islamic state. Article 29 of Indonesia's Constitution however affirms that “the state is based on the belief in the one supreme God.”[lower-alpha 5] Over the past 50 years, many Islamic groups have opposed this secular and pluralist direction, and sporadically have sought to establish an Islamic state. However, the country's mainstream Muslim community, including influential social organisations such as Muhammadiyah and NU, reject the idea. Proponents of an Islamic state argued unsuccessfully in 1945 and throughout the parliamentary democracy period of the 1950s for the inclusion of language (the "Jakarta Charter") in the Constitution's preamble making it obligatory for Muslims to follow shari'a.

.jpg)

An Islamist political movement aspired to form an Islamic state, established Darul Islam/Tentara Islam Indonesia (DI/TII) in 1949, which launched an armed rebellion against the Republic throughout the 1950s. The outbreak of Islamic state took place in multiple provinces, started in West Java led by Kartosoewirjo, the rebellion also spread to Central Java, South Sulawesi and Aceh. The Islamist armed rebellion was successfully cracked down in 1962. The movement has alarmed the Sukarno administration to the potential threat of political Islam against the Indonesian Republic.[96]

During the Suharto regime, the Government prohibited all advocacy of an Islamic state. With the loosening of restrictions on freedom of speech and religion that followed the fall of Suharto in 1998, proponents of the "Jakarta Charter" resumed advocacy efforts. This proved the case prior to the 2002 Annual Session of the People's Consultative Assembly (MPR), a body that has the power to change the Constitution. The nationalist political parties, regional representatives elected by provincial legislatures, and appointed police, military, and functional representatives, who together held a majority of seats in the MPR, rejected proposals to amend the Constitution to include shari'a, and the measure never came to a formal vote. The MPR approved changes to the Constitution that mandated that the Government increase "faith and piety" in education. This decision, seen as a compromise to satisfy Islamist parties, set the scene for a controversial education bill signed into law in July 2003.

On 9 May 2017, Indonesian politician Basuki Tjahaja Purnama has been sentenced to two years in prison by the North Jakarta District Court after being found guilty of committing a criminal act of blasphemy.[97]

Shari'a in Aceh

Shari'a generated debate and concern during 2004, and many of the issues raised touched on religious freedom. Aceh remained the only part of the country where the central Government specifically authorised shari'a. Law 18/2001 granted Aceh special autonomy and included authority for Aceh to establish a system of shari'a as an adjunct to, not a replacement for, national civil and criminal law. Before it could take effect, the law required the provincial legislature to approve local regulations ("qanun") incorporating shari'a precepts into the legal code. Law 18/2001 states that the shari'a courts would be "free from outside influence by any side." Article 25(3) states that the authority of the court will only apply to Muslims. Article 26(2) names the national Supreme Court as the court of appeal for Aceh's shari'a courts.

Aceh is the only province that has shari'a courts. Religious leaders responsible for drafting and implementing the shari'a regulations stated that they had no plans to apply criminal sanctions for violations of shari'a. Islamic law in Aceh, they said, would not provide for strict enforcement of fiqh or hudud, but rather would codify traditional Acehnese Islamic practice and values such as discipline, honesty, and proper behaviour. They claimed enforcement would not depend on the police but rather on public education and societal consensus.

Because Muslims make up the overwhelming majority of Aceh's population, the public largely accepted shari'a, which in most cases merely regularised common social practices. For example, a majority of women in Aceh already covered their heads in public. Provincial and district governments established shari'a bureaus to handle public education about the new system, and local Islamic leaders, especially in North Aceh and Pidie, called for greater government promotion of shari'a as a way to address mounting social ills. The imposition of martial law in Aceh in May 2003 had little impact on the implementation of shari'a. The Martial Law Administration actively promoted shari'a as a positive step toward social reconstruction and reconciliation. Some human rights and women's rights activists complained that implementation of shari'a focused on superficial issues, such as proper Islamic dress, while ignoring deep-seated moral and social problems, such as corruption.

Ahmadiyya

In 1980 the Indonesian Council of Ulamas (MUI) issued a "fatwa" (a legal opinion or decree issued by an Islamic religious leader) declaring that the Ahmadis are not a legitimate form of Islam. In the past, mosques and other facilities belonging to Ahmadis had been damaged by offended Muslims in Indonesia; more recently, rallies have been held demanding that the sect be banned and some religious clerics have demanded Ahmadis be killed.[98][99]

See also

Notes

- The government officially recognizes six religions: Islam, Protestantism, Roman Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Confucianism;[12] although the government also officially recognizes Indonesian indigenous religions.[13]

- The Maluku Islands in the Indonesian archipelago were known as the "spice islands". The country's natural spices, including nutmeg, pepper, clove, were highly prized. Other popular trade items of the area include sandalwood, rubber and teak.

- See 2002 Bali bombings, 2003 Marriott Hotel bombing

- “Conservatism” in this sense connotes the adherence toward the perceived orthodoxy of Islamic principles, rather than the commitment to the Indonesian cultural and societal traditions. Therefore under this framing, it may entail the proponents of conservatism advocating for the societal changes, while the proponents of liberalism opposing against them.

- The Indonesian Constitution provides "all persons the right to worship according to their own religion or belief" and states that "the nation is based upon belief in one supreme God." The Government generally respects these provisions; however, some restrictions exist on certain types of religious activity and on unrecognised religions. The Ministry of Religious Affairs recognizes official status of six faiths: Islam, Catholicism, Protestantism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Confucianism. Religious organisations other than the six recognised faiths can register with the Government, but only with the Ministry for Culture and Tourism and only as social organisations. This restricts certain religious activities. Unregistered religious groups cannot rent venues to hold services and must find alternative means to practice their faiths. Atheism and agnosticism are not explicitly outlawed but socially stigmatised.

References

- "Penduduk Menurut Wilayah dan Agama yang Dianut" [Population by Region and Religion]. Sensus Penduduk 2010. Jakarta, Indonesia: Badan Pusat Statistik. 15 May 2010. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

Religion is belief in Almighty God that must be possessed by every human being. Religion can be divided into Muslim, Christian (Protestant), Catholic, Hindu, Buddhist, Hu Khong Chu, and Other Religions.

Muslim 207,176,162 (87.18%), Christian (Protestant) 16,528,513 (6.96), Catholic 6,907,873 (2.91), Hindu 4,012,116 (1.69), Buddhist 1,703,254 (0.72), Confucianism 117,091 (0.05), Other 299,617 (0.13), Not Stated 139,582 (0.06), Not Asked 757,118 (0.32), Total 237,641,326 - "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- Reza, Imam. "Shia Muslims Around the World". Archived from the original on 22 May 2009. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

approximately 400,000 persons who subscribe to the Ahmadiyya

- "International Religious Freedom Report 2008". US Department of State. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- "Sunni and Shia Muslims". 27 January 2011.

- Religious clash in Indonesia kills up to six, Straits Times, 6 February 2011

- "Chapter 1: Religious Affiliation". The World’s Muslims: Unity and Diversity. Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 9 August 2012. Retrieved 6 September 2015.

- Rhoads Murphey (1992). A history of Asia. HarperCollins.

- Burhanudin, Jajat; Dijk, Kees van (31 January 2013). Islam in Indonesia: Contrasting Images and Interpretations. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789089644237 – via Google Books.

- Lamoureux, Florence (1 January 2003). Indonesia: A Global Studies Handbook. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576079133 – via Internet Archive.

- Martin, Richard C. (2004). Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World Vol. 2 M-Z. Macmillan.

- Yang, Heriyanto (August 2005). "The History and Legal Position of Confucianism in Post Independence Indonesia" (PDF). Marburg Journal of Religion. 10 (1): 8. Retrieved 2 October 2006.

- "Pemerintah Setuju Penghayat Kepercayaan Tertulis di Kolom Agama KTP". Detikcom. 8 May 2017. Retrieved 11 July 2017.

- Randall L. Pouwels (2002), Horn and Crescent: Cultural Change and Traditional Islam, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521523097, pp 88–159

- MN Pearson (2000), The Indian Ocean and the Red Sea, in The History of Islam in Africa (Ed: Nehemia Levtzion, Randall Pouwels), Ohio University Press, ISBN 978-0821412978, Chapter 2

- Clifford Geertz; Aswab Mahasin; Bur Rasuanto (1983). Abangan, santri, priyayi: dalam masyarakat Jawa, Issue 4 of Siri Pustaka Sarjana. Pustaka Jaya, original from the University of Michigan, digitized on 24 June 2009.

- Von Der Mehden, Fred R. (1995). "Indonesia.". In John L. Esposito. The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Modern Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- "Apa yang Dimaksud dengan Islam Nusantara?". Nahdlatul Ulama (in Indonesian). 22 April 2015.

- Heyder Affan (15 June 2015). "Polemik di balik istiIah 'Islam Nusantara'". BBC Indonesia (in Indonesian).

- Palmier, Leslie H. (September 1954). "Modern Islam in Indonesia: The Muhammadiyah After Independence". Pacific Affairs. 27 (3): 257. JSTOR 2753021.

- Bruinessen, Martin van, Contemporary Developments in Indonesian Islam Explaining the 'Conservative Turn' . ISEAS Publishing, 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- Hasan, Noorhaidi, The Salafi Movement in Indonesia. Project Muse, 2007. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- Reza, Imam. "Shia Muslims Around the World". Archived from the original on 22 May 2009. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- "Indonesia". The Association of Religious Data. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- Ahmad Najib Burhani (18 December 2013). "The Ahmadiyya and the Study of Comparative Religion in Indonesia: Controversies and Influences". Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations. 25. Taylor & Francis. pp. 143–144.

- Leonard Leo. International Religious Freedom (2010): Annual Report to Congress. DIANE Publishing. pp. 261–. ISBN 978-1-4379-4439-6.

- Fatima Zainab Rahman (2014). "State restrictions on the Ahmadiyya sect in Indonesia and Pakistan: Islam or political survival?". Australian Journal of Political Science. Routledge. 49 (3): 418–420.

- Feener, R. Michael. Muslim legal thought in modern Indonesia. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- Mujani, Saiful and Liddle, R. William. Politics, Islam and Public Opinion. (2004) Journal of Democracy, 15:1, p.109-123.

- Ranjan Ghosh (4 January 2013). Making Sense of the Secular: Critical Perspectives from Europe to Asia. Routledge. p. 202. ISBN 978-1-136-27721-4.

- "Nahdlatul Ulama (Muslim organization), Indonesia".

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 14 September 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Bruinessen, Martin van. "Islamic state or state Islam? Fifty years of state-Islam relations in Indonesia" Archived 27 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine in Ingrid Wessel (Hrsg.), Indonesien am Ende des 20. Jahrhunderts. Hamburg: Abera-Verlag, 1996, pp. 19–34.

- Wakhid Sugiyarto, Study of the 'Santrinisation' process Archived 19 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Negeri Champa, Jejak Wali Songo di Vietnam. detik travel. Retrieved 3 October 2017.

- Raden Abdulkadir Widjojoatmodjo (November 1942). "Islam in the Netherlands East Indies". The Far Eastern Quarterly. 2 (1): 48–57. doi:10.2307/2049278. JSTOR 2049278.

- Audrey Kahin (2015). Historical Dictionary of Indonesia. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-0-8108-7456-5.

- M.C. Ricklefs (2008). A History of Modern Indonesia Since C.1200. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 17–19, 22, 34–42. ISBN 978-1-137-05201-8.

- Juergensmeyer, Mark; Roof, Wade Clark (2012). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. SAGE. ISBN 978-0-7619-2729-7.

- AQSHA, DARUL (13 July 2010). "Zheng He and Islam in Southeast Asia". The Brunei Times. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- Sanjeev Sanyal (6 August 2016). "History of Indian Ocean shows how old rivalries can trigger rise of new forces". Times of India.

- Duff, Mark (25 October 2002). "Islam in Indonesia". BBC News.

- Feener, Michael R. and Laffan, Michael F. Sufi Scents across the Indian Ocean: Yemeni Hagiography and the Earliest History of Southeast Asian Islam. Archipel 70 (2005), p.185-208.

- Aquino, Michael. "An Overview of Balinese Culture". seasia.about.com. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- Ricklefs, M.C. (1991). A History of Modern Indonesia since c.1300, 2nd Edition. London: MacMillan. p. 3. ISBN 0-333-57689-6.

- Ehito Kimura (2002). "Indonesia and Islam Before and After 9/11".

- Ricklefs (1991), p. 285

- Ricklefs, M.C. (1991). A History of Modern Indonesia 1200–2004. London: MacMillan.

- Fred R. Von der Mehden, Two Worlds of Islam: Interaction Between Southeast Asia and the Middle East, 1993

- Ricklefs, M.C. (1991). A History of Modern Indonesia 1200–2004. London: MacMillan. pp. 353–356.

- Kementerian Penerangan Republik Indonesia (1951). Kepartaian di Indonesia (PDF). Jakarta: Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat Republik Indonesia. p. 72.

- Sjafnir Aboe Nain, 2004, Memorie Tuanku Imam Bonjol (MTIB), transl., Padang: PPIM.

- Indonesian State Secretariat, Daftar Nama Pahlawan (1).

- Mirnawati 2012, pp. 56–57.

- Holt, Peter Malcolm; Ann K. S. Lambton; Bernard Lewis (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam. Cambridge University Press. pp. 191–192. ISBN 0-521-29137-2.

- Hj. Rasuna Said. Pahlawan Center. Retrieved 29 November 2017.

- Wahid 1996, pp. 19–51.

- Saleh, Modern Trends in Islamic Theological Discourse in 20th Century Indonesia pp.230,233

- Barton (2002), Biografi Gus Dur, LKiS, p.102

- Abdullah Saeed, Approaches to the Qur'an in Contemporary Indonesia. Oxford University Press, 2005, p.78-79. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- Gillespie, P 2007, "Current Issues in Indonesian Islam: Analysing the 2005 Council of Indonesian Ulama Fatwa N0. 7" Journal of Islamic Studies Vol 18, No. 2 pp. 202–240.

- "Saudi Arabia Is Redefining Islam for the World's Largest Muslim Nation". 2 March 2017.

- "In Indonesia, Madrassas of Moderation". 10 February 2015.

- PERLEZ, JANE (5 July 2003). "Saudis Quietly Promote Strict Islam in Indonesia". New York Times. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- Shane, Scott (25 August 2016). "Saudis and Extremism: 'Both the Arsonists and the Firefighters'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- Scott, Margaret (27 October 2016). "Indonesia: The Saudis Are Coming [complete article behind paywall]". New York Review of Books. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- Ricklefs (1991), p. 287.

- R. B. Cribb; Audrey Kahin (2004). Historical Dictionary of Indonesia. Scarecrow Press. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-8108-4935-8.

- Ricklefs (1994), p. 285

- Kersten, Carool. Islam in Indonesia the Contest for Society, Ideas and Values. (2015) C. Hurst & Co.

- Moch Nur Ichwan, Towards a Puritanical Moderate Islam: The Majelis Ulama Indonesia and the Politics of Religious Orthodoxy. ISEAS Publishing. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- Hefner, Robert. Civil Islam: Muslims and Democratization in Indonesia. (2000) Princeton University Press, p.218.

- Menchik, Jeremy. Islam and Democracy in Indonesia Tolerance without Liberalism. (2017) Cambridge University Press, p.15.

- Relasi PAN-Muhammadiyah. Republika. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- Nahdlatul Ulama. Berkley Center for Religion, Peace & World Affairs. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- van Bruinessen, Martin. New Leadership, New Policies? The Nahdlatul Ulama Congress in Makassar. Inside Indonesia 101, July–September 2010. Online at <www.insideindonesia.org/>.

- McDonald, Hamish (30 June 2008). "Fighting terror with smart weaponry". Sydney Morning Herald. p. 17.

- Islam Indonesia Kelak Akan Kaku dan Keras? NU.or.id. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- Azra, Azyumardi. ‘Islam Nusantara Islam Indonesia (3)’. Republika, Thursday, 2 July 2015.

- M Andika Putra; Raja Eben Lumbanrau (17 January 2017). "Jejak FPI dan Status 'Napi' Rizieq Shihab". CNN Indonesia (in Indonesian).

- Conservative Islam Has Scored a Disquieting Victory in Indonesia's Normally Secular Politics. TIME. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- Islam Nusantara And Its Critics: The Rise Of NU’s Young Clerics – Analysis. Eurasia Review. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- Platzdasch, Bernhard. Islamism in Indonesia. ISEAS Publishing, (2009).

- National Geographic Traveller Indonesia, Vol 1, No 6, 2009, Jakarta, Indonesia, page 54

- "Figural Representation in Islamic Art". metmuseum.org.

- "Pesona Batik Jambi" (in Indonesian). Padang Ekspres. 16 November 2008. Archived from the original on 17 August 2013. Retrieved 24 October 2011.

- Poplawska, Marzanna (2004). "Wayang Wahyu as an Example of Christian Forms of Shadow Theatre". Asian Theatre Journal. Johns Hopkins University Press. 21 (2): 194–202. doi:10.1353/atj.2004.0024.

- "Amir Hamzah, uncle of the Prophet Muhammad, spreader of Islam, and hero of the Serat Menak". Asian Art Education.

- Gunawan Tjahjono (1998). Indonesian Heritage-Architecture. Singapore: Archipelago Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 981-3018-30-5.

- Turner, Peter (November 1995). Java. Melbourne: Lonely Planet. pp. 78–79. ISBN 0-86442-314-4.

- Dina Fatimah. "KAJIAN Arsitektur pada Masjid Bingkudu di Minangkabau dilihat dari Aspek Nilai dan Makna" (PDF).

- Abdullah Mubarok (21 February 2016). "PDIP: Kopiah Bagian Dari identitas Nasional" (in Indonesian). Inilah.com. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- Yasmin Ahmad Kamil (30 June 2015). "They know what you need for Raya". The Star. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- Bachyul Jb, Syofiardi (1 March 2006). "'Tabuik' festival: From a religious event to tourism". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 27 January 2007.

- Pringle, Robert (2010). Understanding Islam in Indonesia: Politics and Diversity. Editions Didier Millet. ISBN 9789814260091.

- Dijk, C. van (Cornelis) (1981). Rebellion under the banner of Islam : the Darul Islam in Indonesia. The Hague: M. Nijhoff. ISBN 9024761727.

- "Jakarta governor Ahok found guilty of blasphemy, jailed for two years". The Guardian. 9 May 2017.

- Ahmadiyya (Nearly) banned. Indonesia Matters

- "Indonesian Muslims rally for ban on Ahmadiyya sect". Reuters. 20 April 2008.

Further reading

- Ricklefs, M. C. (1991). A History of Modern Indonesia since c.1300, Second Edition. MacMillan. ISBN 0-333-57689-6.

- Gade, Anna M. Perfection Makes Practice: Learning, Emotion, and the Recited Qur’ân in Indonesia. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2004.