Junk (ship)

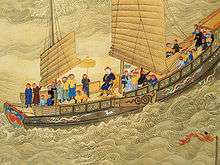

A junk is a type of Chinese sailing ship with fully battened sails. They were developed during the Song dynasty (960–1279) based on Austronesian ship designs, examples of which have been trading with the Eastern Han dynasty since the 2nd century AD.[1][2] They continued to evolve in the later dynasties, and were predominantly used by Chinese traders throughout Southeast Asia. They were found, and in lesser numbers are still found, throughout Southeast Asia and India, but primarily in China. Found more broadly today is a growing number of modern recreational junk-rigged sailboats. Chinese junks referred to many types of coastal or river ships. They were usually cargo ships, pleasure boats, or houseboats. They vary greatly in size and there are significant regional variations in the type of rig, however they all employ fully battened sails.

The term "junk" (Portuguese junco; Dutch jonk; and Spanish junco[3]) was also used in the colonial period to refer to any large to medium-sized ships of the Austronesian cultures in Island Southeast Asia, with or without the junk rig.[4] Examples include the Indonesian and Malaysian jong, the Philippine lanong, and the Maluku kora kora.[5]

Etymology

Views diverge on whether the origin of the word is from a dialect of Chinese, or from a Javanese word. The term may stem from the Chinese chuán (船, "boat; ship"), also based on and pronounced as [dzuːŋ] (Pe̍h-ōe-jī: chûn) in the Minnan variant of Chinese, or zhōu (舟), the old word for a sailing vessel. The modern Standard Chinese word for an ocean-going wooden cargo vessel is cáo (艚).[6]

Pierre-Yves Manguin and Zoetmulder, amongst others, points to an Old Javanese origin, in the form of "jong". The word can be traced from an Old Javanese inscription in the 9th century.[7][8] It entered the Malay and Chinese languages by 15th century, where a Chinese word list identifies it as Malay word for ship. The Malay Maritime Code, first drawn up in the late 15th century, uses jong frequently as the word for freight ships.[9] European writings from 1345 through 1601 use a variety of related terms, including jonque (French), ioncque (Italian), joanga or juanga (Spanish), junco (Portuguese), and jonk (Dutch).[10] These terms were applied to all large ships in Southeast Asia, not only to Chinese ships.[11]

The origin of the word "junk" in the English language, can be traced to the Potuguese word junco, which is rendered from the Arabic word j-n-k (جنك). This word comes from the fact that the Arabic script cannot represent the digraph "ng".[12]:37 The word was used to denote both Javanese/Malay ship (jong) and Chinese ship (chuán), even though the two were markedly different vessels. After the disappearance of jongs in the 17th century, the meaning of "junk" (and other similar words in European languages), which until then was used as a transcription of the word "jong" in Malay and Javanese, changed its meaning to exclusively Chinese ship (chuán) only.[13][14]:222

Construction

The historian Herbert Warington Smyth considered the junk as one of the most efficient ship designs, stating that "As an engine for carrying man and his commerce upon the high and stormy seas as well as on the vast inland waterways, it is doubtful if any class of vessel… is more suited or better adapted to its purpose than the Chinese or Indian junk, and it is certain that for flatness of sail and handiness, the Chinese rig is unsurpassed."[15]

Sails

The sail of Chinese junks is an adoption of the Malay junk sail, which used vegetable matting attached to bamboo battens, a practice originated from South East Asia.[16][17] The full-length battens keep the sail flatter than ideal in all wind conditions. Consequently, their ability to sail close to the wind is poorer than other fore-and-aft rigs.[18]

Hull

Classic junks were built of softwoods (although after the 17th century teak was used in Guangdong) with the outside shape built first. Then multiple internal compartment/bulkheads accessed by separate hatches and ladders, reminiscent of the interior structure of bamboo, were built in. Traditionally, the hull has a horseshoe-shaped stern supporting a high poop deck. The bottom is flat in a river junk with no keel (similar to a sampan), so that the boat relies on a daggerboard,[19] leeboard or very large rudder to prevent the boat from slipping sideways in the water.[20] Ocean-going junks have a curved hull in section with a large amount of tumblehome in the topsides. The planking is edge nailed on a diagonal. Iron nails or spikes have been recovered from a Canton dig dated to circa 221 BC. For caulking the Chinese used a mix of ground lime with Tung oil together with chopped hemp from old fishing nets which set hard in 18 hours, but usefully remained flexible. Junks have narrow waterlines which accounts for their potential speed in moderate conditions, although such voyage data as we have indicates that average speeds on voyage for junks were little different from average voyage speeds of almost all traditional sail, i.e. around 4–6 knots. The largest junks, the treasure ships commanded by Ming dynasty Admiral Zheng He, were built for world exploration in the 15th century, and according to some interpretations may have been over 120 metres (390 ft) in length. This conjecture was based on the size of a rudder post that was found and misinterpreted, using formulae applicable to modern engine powered ships. More careful analysis shows that the rudder post that was found is actually smaller than the rudder post shown for a 70' long Pechili Trader in Worcester's "Junks and Sampans of the Yangtze".

Another characteristic of junks, interior compartments or bulkheads, strengthened the ship and slowed flooding in case of holing. Ships built in this manner were written of in Zhu Yu's book Pingzhou Table Talks, published by 1119 during the Song dynasty.[21] Again, this type of construction for Chinese ship hulls was attested to by the Moroccan Muslim Berber traveler Ibn Battuta (1304–1377 AD), who described it in great detail (refer to Technology of the Song dynasty).[22] Although some historians have questioned whether the compartments were watertight, most believe that watertight compartments did exist in Chinese junks because although most of the time there were small passageways (known as limber holes) between compartments, these could be blocked with stoppers and such stoppers have been identified in wrecks. All wrecks discovered so far have limber holes; these are different from the free flooding holes that are located only in the foremost and aftermost compartments, but are at the base of the transverse bulkheads allowing water in each compartment to drain to the lowest compartment, thus facilitating pumping. It is believed from evidence in wrecks that the limber holes could be stopped either to allow the carriage of liquid cargoes or to isolate a compartment that had sprung a leak.

Benjamin Franklin wrote in a 1787 letter on the project of mail packets between the United States and France:

As these vessels are not to be laden with goods, their holds may without inconvenience be divided into separate apartments, after the Chinese manner, and each of these apartments caulked tight so as to keep out water.

— Benjamin Franklin, 1787[23]

In 1795, Sir Samuel Bentham, inspector of dockyards of the Royal Navy, and designer of six new sailing ships, argued for the adoption of "partitions contributing to strength, and securing the ship against foundering, as practiced by the Chinese of the present day". His idea was not adopted. Bentham had been in China in 1782, and he acknowledged that he had got the idea of watertight compartments by looking at Chinese junks there. Bentham was a friend of Isambard Brunel, so it is possible that he had some influence on Brunel's adoption of longitudinal, strengthening bulkheads in the lower deck of the SS Great Britain. Bentham had already by this time designed and had built a segmented barge for use on the Volga River, so the idea of transverse hull separation was evidently in his mind. Perhaps more to the point, there is a very large difference between the transverse bulkheads in Chinese construction, which offer no longitudinal strengthening, and the longitudinal members which Brunel adopted, almost certainly inspired by the iron bridge and boiler engineering in which he and his contemporaries in iron shipbuilding innovation were most versed.

Due to the numerous foreign primary sources that hint to the existence of true watertight compartments in junks, historians such as Joseph Needham proposed that the limber holes were stopped up as noted above in case of leakage. He addresses the quite separate issue of free-flooding compartments on pg 422 of Science and Civilisation in Ancient China:

Less well known is the interesting fact that in some types of Chinese craft the foremost (and less frequently also the aftermost) compartment is made free-flooding. Holes are purposely contrived in the planking. This is the case with the salt-boats which shoot the rapids down from Tzuliuching in Szechuan, the gondola-shaped boats of the Poyang Lake, and many sea going junks. The Szechuanese boatmen say that this reduces resistance to the water to a minimum, though such a claim makes absolutely no hydrodynamic sense, and the device is thought to cushion the shocks of pounding when the boat pitches heavily in the rapids, as it acquires and discharges water ballast rapidly supposedly just at the time when it is most desirable to counteract buffeting at stem and stern. As with too many such claims, there has been no empirical testing of them and it seems unlikely that the claims would stand up to such testing since the diameter or number of holes needed for such rapid flooding and discharging would be so great as to significantly weaken the vulnerable fore and aft parts of the vessel. The sailors say, as sailors all over the world are inclined to do when conjuring up answers to landlubbers' questions, that it stops junks flying up into the wind. It may be the reality at the bottom of the following story, related by Liu Ching-Shu of the +5th century, in his book I Yuan (Garden of Strange Things)

In Fu-Nan (Cambodia) gold is always used in transactions. Once there were (some people who) having hired a boat to go from east to west near and far, had not reached their destination when the time came for the payment of the pound (of gold) which had been agreed upon. They therefore wished to reduce the quantity (to be paid). The master of the ship then played a trick upon them. He made (as it were) a way for the water to enter the bottom of the boat, which seemed to be about to sink, and remained stationary, moving neither forward nor backward. All the passengers were very frightened and came to make offerings. The boat (afterwards) returned to its original state.

This, however, would seem to have involved openings which could be controlled, and the water pumped out afterwards. This was easily effected in China (still seen in Kuangtung and Hong Kong), but the practice was also known in England, where the compartment was called the 'wet-well', and the boat in which it was built, a 'well-smack'. If the tradition is right that such boats date in Europe from +1712 then it may well be that the Chinese bulkhead principle was introduced twice, first for small coastal fishing boats at the end of the seventeenth century, and then for large ships a century later. However, the wet well is probably a case of parallel invention since its manner of construction is quite different from that of Chinese junks, the wet well quite often not running the full width of the boat, but only occupying the central part of the hull either side of the keel.

More to the point[24] wet wells were apparent in Roman small craft of the 5th century CE.

Leeboards and centerboards

Leeboards and centerboards, used to stabilize the junk and to improve its capability to sail upwind, are documented from a 759 AD book by Li Chuan. The innovation was adopted by Portuguese and Dutch ships around 1570. Junks often employ a daggerboard that is forward on the hull which allows the center section of the hull to be free of the daggerboard trunk allowing larger cargo compartments. Because the daggerboard is located so far forward, the junk must use a balanced rudder to counteract the imbalance of lateral resistance.

Other innovations included the square-pallet bilge pump, which was adopted by the West during the 16th century for work ashore, the western chain pump, which was adopted for shipboard use, being of a different derivation. Junks also relied on the compass for navigational purposes. However, as with almost all vessels of any culture before the late 19th century, the accuracy of magnetic compasses aboard ship, whether from a failure to understand deviation (the magnetism of the ship's iron fastenings) or poor design of the compass card (the standard drypoint compasses were extremely unstable), meant that they did little to contribute to the accuracy of navigation by dead reckoning. Indeed, a review of the evidence shows that the Chinese embarked magnetic pointer was probably little used for navigation. The reasoning is simple. Chinese mariners were as able as any and, had they needed a compass to navigate, they would have been aware of the almost random directional qualities when used at sea of the water bowl compass they used. Yet that design remained unchanged for some half a millennium. Western sailors, coming upon a similar water bowl design (no evidence as to how has yet emerged) very rapidly adapted it in a series of significant changes such that within roughly a century the water bowl had given way to the dry pivot, a rotating compass card a century later, a lubberline a generation later and gimbals seventy or eighty years after that. These were necessary because in the more adverse climatic context of north western Europe, the compass was needed for navigation. Had similar needs been felt in China, Chinese mariners would also have come up with fixes. They didn't.[25]

Steering

Junks employed stern-mounted rudders centuries before their adoption in the West for the simple reason that Western hull forms, with their pointed sterns, obviated a centreline steering system until technical developments in Scandinavia created the first, iron mounted, pintle and gudgeon 'barn door' western examples in the early 12th century CE. A second reason for this slow development was that the side rudders in use were, contrary to a lot of very ill-informed opinion, extremely efficient.[26] Thus the junk rudder's origin, form and construction was completely different in that it was the development of a centrally mounted stern steering oar, examples of which can also be seen in Middle Kingdom (c.2050–1800 BCE) Egyptian river vessels. It was an innovation which permitted the steering of large ships and due to its design allowed height adjustment according to the depth of the water and to avoid serious damage should the junk ground. A sizable junk can have a rudder that needed up to twenty members of the crew to control in strong weather. In addition to using the sail plan to balance the junk and take the strain off the hard to operate and mechanically weakly attached rudder, some junks were also equipped with leeboards or dagger boards. The world's oldest known depiction of a stern-mounted rudder can be seen on a pottery model of a junk dating from before the 1st century AD,[27] though some scholars think this may be a steering oar; a possible interpretation given is that the model is of a river boat that was probably towed or poled.

From sometime in the 13th to 15th centuries, many junks began incorporating "fenestrated" rudders (rudders with large diamond-shaped holes in them), probably adopted to lessen the force needed to direct the steering of the rudder.

The rudder is reported to be the strongest part of the junk. In the Tiangong Kaiwu "Exploitation of the Works of Nature" (1637), Song Yingxing wrote, "The rudder-post is made of elm, or else of langmu or of zhumu." The Ming author also applauds the strength of the langmu wood as "if one could use a single silk thread to hoist a thousand jun or sustain the weight of a mountain landslide."

History

2nd century (Han dynasty)

However, large Austronesian trading ships docking in Chinese ports with as many as four sails were recorded by scholars as early as the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE). They called them the kunlun bo or kunlun po (崑崙舶, lit. "ship of the [dark-skinned] Kunlun people"). They were booked by Chinese Buddhist pilgrims for passage to Southern India and Sri Lanka.[28][29]

The 3rd century book "Strange Things of the South" (南州異物志) by Wan Chen (萬震) describes one of these Austronesian ships as being capable of carrying 700 people together with 260 tons of cargo ("more than 10,000 "斛"). He explains the ships' sail design as follows:

The four sails do not face directly forward, but are set obliquely, and so arranged that they can all be fixed in the same direction, to receive the wind and to spill it. Those sails which are behind the most windward one receiving the pressure of the wind, throw it from one to the other, so that they all profit from its force. If it is violent, (the sailors) diminish or augment the surface of the sails according to the conditions. This oblique rig, which permits the sails to receive from one another the breath of the wind, obviates the anxiety attendant upon having high masts. Thus these ships sail without avoiding strong winds and dashing waves, by the aid of which they can make great speed.

— Wan Chen, [30]

A 260 CE book by K'ang T'ai (康泰) described ships with seven sails called po for transporting horses that could travel as far as Syria. He also made reference to monsoon trade between the islands (or archipelago), which took a month and a few days in a large po.[31]

Southern Chinese junks were based on keelled and multi-planked Austronesian jong (known as po by the Chinese, from Javanese or Malay perahu - large ship).[32]:613[33]:193 Southern Chinese junks showed characteristics of Austronesian jong: V-shaped, double-ended hull with a keel, and using timbers of tropical origin. This is different from northern Chinese junks, which are developed from flat bottomed riverine boats.[11]:20–21 The northern Chinese junks had flat bottoms, no keel, no frames (only water-tight bulkheads), transom stern and stem, would have been built out of pine or fir wood, and would have its planks fastened with iron nails or clamps.[32]:613

10–13th century (Song dynasty)

The trading dynasty of the Song developed the first junks based on Southeast Asian ships. By this era they also have adopted the Malay junk sail.[17] The ships of the Song, both mercantile and military, became the backbone of the navy of the following Yuan dynasty. In particular the Mongol invasions of Japan (1274–84), as well as the Mongol invasion of Java (both failed), essentially relied on recently acquired Song naval capabilities. Worcester estimates that Yuan junks were 11 m (36 ft) in beam and over 30 m (100 ft) long. In general they had no keel, stempost, or sternpost. They did have centreboards, and watertight bulkhead to strengthen the hull, which added great weight. Further excavations showed that this type of vessel was common in the 13th century.[34] By using the ratio between number of soldiers and ships in both invasions, it can be concluded that each ship may carry 20-70 men.[35]

14th century (Yuan dynasty)

The enormous dimensions of the Chinese ships of the Medieval period are described in Chinese sources, and are confirmed by Western travelers to the East, such as Marco Polo, Ibn Battuta and Niccolò da Conti. According to Ibn Battuta, who visited China in 1347: {{quote|…We stopped in the port of Calicut, in which there were at the time thirteen Chinese vessels, and disembarked. On the China Sea traveling is done in Chinese ships only, so we shall describe their arrangements. The Chinese vessels are of three kinds; large ships called chunks (junks), middle sized ones called zaws (dhows) and the small ones kakams. The large ships have anything from twelve down to three sails, which are made of bamboo rods plaited into mats. They are never lowered, but turned according to the direction of the wind; at anchor they are left floating in the wind.

A ship carries a complement of a thousand men, six hundred of whom are sailors and four hundred men-at-arms, including archers, men with shields and crossbows, who throw naphtha. Three smaller ones, the "half", the "third" and the "quarter", accompany each large vessel. These vessels are built in the towns of Zaytun (a.k.a. Zaitun; today's Quanzhou; 刺桐) and Sin-Kalan. The vessel has four decks and contains rooms, cabins, and saloons for merchants; a cabin has chambers and a lavatory, and can be locked by its occupants.

This is the manner after which they are made; two (parallel) walls of very thick wooden (planking) are raised and across the space between them are placed very thick planks (the bulkheads) secured longitudinally and transversely by means of large nails, each three ells in length. When these walls have thus been built the lower deck is fitted in and the ship is launched before the upper works are finished.[36]|Ibn Battuta

15–17th century (Ming dynasty)

From the mid-15th to early 16th century, all Chinese maritime trading was banned under the Ming Dynasty. The shipping and ship-building knowledge acquired during the Song and Yuan dynasties gradually declined during this period.[37]

Expedition of Zheng He

The largest junks ever built were possibly those of Admiral Zheng He, for his expeditions in the Indian Ocean (1405 to 1433), although this is disputed as no contemporary records of the sizes of Zheng He's ships are known. Instead the dimensions are based on Sanbao Taijian Xia Xiyang Ji Tongsu Yanyi (1597), a romanticized version of the voyages written by Luo Maodeng nearly two centuries later [38]. Maodeng's novel describes Zheng He's ships as follows:

- Treasure ships, used by the commander of the fleet and his deputies (Nine-masted junks, claimed by the Ming Shi to be about 420 feet long and 180 feet wide).

- Horse ships, carrying tribute goods and repair material for the fleet (Eight-masted junks, about 340 feet long and 140 feet wide)

- Supply ships, containing food-staple for the crew (Seven-masted junks, about 260 feet long and 115 feet wide).

- Troop transports (Six-masted junks, about 220 feet long and 83 feet wide).

- Fuchuan warships (Five-masted junks, about 165 feet long).

- Patrol boats (Eight-oared, about 120 feet long).

- Water tankers, with 1 month's supply of fresh water.

Some recent research suggests that the actual length of the biggest treasure ships may have been between 390–408 feet (119–124 m) long and 160–166 feet (49–51 m) wide,[39] while others estimate them to be 200–250 feet (61–76 m) in length.[40]

Capture of Taiwan

In 1661, a naval fleet of 400 junks and 25,000 men led by the Ming loyalist Zheng Chenggong (Cheng Ch'eng-kung in Wade–Giles, known in the West as Koxinga), arrived in Taiwan to oust the Dutch from Zeelandia. Following a nine-month siege, Cheng captured the Dutch fortress Fort Zeelandia. A peace treaty between Koxinga and the Dutch Government was signed at Castle Zeelandia on February 1, 1662, and Taiwan became Koxinga's base for the Kingdom of Tungning.

Javanese

The physical description of Javanese junk differed from Chinese junk. It was made of very thick wood, and as the ship got old, it was fixed with new boards, with four closing boards, stacked together. The rope and the sail was made with woven rattan.[41][42] The jong was made using jaty/jati wood (teak) at the time of this report (1512), at that time Chinese junks are using softwood as the main material.[43] The jong's hull is formed by joining planks to the keel and then to each other by wooden dowels, without using either a frame (except for subsequent reinforcement), nor any iron bolts or nails. The planks are perforated by an auger and inserted with dowels, which remains inside the fastened planks, not seen from the outside.[44] On some of the smaller vessels parts may be lashed together with vegetable fibers.[45] The vessel was similarly pointed at both ends, and carried two oar-like rudders and lateen-rigged sails (actually tanja sail),[note 1] but it may also use junk sail, a sail of Malay origin.[16] It differed markedly from the Chinese vessel, which had its hull fastened by strakes and iron nails to a frame and to structurally essential bulkheads which divided the cargo space. The Chinese vessel had a single rudder on a transom stern, and (except in Fujian and Guangdong) they had flat bottoms without keels.[9]

Encounters with giant jongs were recorded by Western travelers. Giovanni da Empoli said that the junks of Java were no different in their strength than a castle, because the three and four boards, layered one above the other, could not be harmed with artillery. They sailed with their women, children, and families, with everyone mainly keeping to their respective rooms.[46] Portuguese recorded at least two encounters with large Djongs, one was encountered off the coast of Pacem (Samudera Pasai Sultanate) and the other was owned by Pati Unus, who went on to attack Malacca in 1513.[47]:62–64[48] Characteristics of the 2 ships were similar, both were larger than Portuguese ship, built with multiple plankings, resistant to cannon fire, and had two oar-like rudders on the side of the ship.[49] At least Pati Unus' jong was equipped with three layers of sheathing which the Portuguese said over one cruzado in thickness each.[43] The Chinese banned foreign ships from entering Guangzhou, fearing the Javanese or Malay junks would attack and capture the city, because it is said that one of these junk would rout twenty Chinese junks.[43]

Main production location of Djong was mainly constructed in two major shipbuilding centres around Java: north coastal Java, especially around Rembang-Demak (along the Muria strait) and Cirebon; and the south coast of Borneo (Banjarmasin) and adjacent islands. A common feature of these places was their accessibility to forests of teak, this wood was highly valued because of its resistance to shipworm, whereas Borneo itself would supply ironwood.[50] Pegu, which is a large shipbuilding port at the 16th century, also produced jong, built by Javanese who resided there.[43]

Accounts of medieval travellers

Niccolò da Conti in relating his travels in Asia between 1419 and 1444, describes huge junks of about 2,000 tons in weight:

They build some ships much larger than ours, capable of containing 2,000 tons in size, with five sails and as many masts. The lower part is constructed with of three planks, in order to withstand the force of the tempest to which they are much exposed. But some ships are built in compartments, that should one part is shattered, the other portion remaining intact to accomplish the voyage.[51]

- Other translations of the passage give the size as a 2000 butts[52], which would be around a 1000 tons, a butt being half a ton.[note 2]

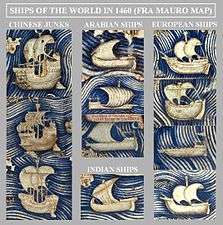

Also, in 1456, the Fra Mauro map described the presence of junks in the Indian Ocean as well as their construction:

The ships called junks (lit. "Zonchi") that navigate these seas carry four masts or more, some of which can be raised or lowered, and have 40 to 60 cabins for the merchants and only one tiller. They can navigate without a compass, because they have an astrologer, who stands on the side and, with an astrolabe in hand, gives orders to the navigator.

— Text from the Fra Mauro map, 09-P25, [53]

Fra Mauro further explains that one of these junks rounded the Cape of Good Hope and travelled far into the Atlantic Ocean, in 1420:

About the year of Our Lord 1420 a ship, what is called an Indian Zoncho, on a crossing of the Sea of India towards the "Isle of Men and Women", was diverted beyond the "Cape of Diab" (Shown as the Cape of Good Hope on the map), through the "Green Isles" (lit. "isole uerde", Cabo Verde Islands), out into the "Sea of Darkness" (Atlantic Ocean) on a way west and southwest. Nothing but air and water was seen for 40 days and by their reckoning they ran 2,000 miles and fortune deserted them. When the stress of the weather had subsided they made the return to the said "Cape of Diab" in 70 days and drawing near to the shore to supply their wants the sailors saw the egg of a bird called roc, which egg is as big as an amphora.

— Text from Fra Mauro map, 10-A13, [54]

Asian trade

Chinese junks were used extensively in Asian trade during the 16th and 17th century, especially to Southeast Asia and to Japan, where they competed with Japanese Red Seal Ships, Portuguese carracks and Dutch galleons. Richard Cocks, the head of the English trading factory in Hirado, Japan, recorded that 50 to 60 Chinese junks visited Nagasaki in 1612 alone.

These junks were usually three masted, and averaging between 200 and 800 tons in size, the largest ones having around 130 sailors, 130 traders and sometimes hundreds of passengers.

19th century (Qing dynasty)

Large, ocean-going junks played a key role in Asian trade until the 19th century. One of these junks, Keying, sailed from China around the Cape of Good Hope to the United States and England between 1846 and 1848. Many junks were fitted out with carronades and other weapons for naval or piratical uses. These vessels were typically called "war junks" or "armed junks" by Western navies which began entering the region more frequently in the 18th century. The British, Americans and French fought several naval battles with war junks in the 19th century, during the First Opium War, Second Opium War and in between.

At sea, junk sailors co-operated with their Western counterparts. For example, in 1870 survivors of the English barque Humberstone shipwrecked off Formosa, were rescued by a junk and landed safely in Macao.[55]

20th century

_en_Tek_Hwa_Seng_bij_Poeloe_Samboe_TMnr_10010680.jpg)

In 1938, E. Allen Petersen escaped the advancing Japanese armies by sailing a 36-foot (11 m) junk, Hummel Hummel, from Shanghai to California with his wife Tani and two White Russians (Tsar loyalists).[56] In 1939, Richard Halliburton was lost at sea with his crew while sailing a specially constructed junk, Sea Dragon, from Hong Kong to the World Exposition in San Francisco.

In 1955, six young men sailed a Ming dynasty-style junk from Taiwan to San Francisco. The four-month journey aboard the Free China was captured on film and their arrival into San Francisco made international front-page news. The five Chinese-born friends saw an advertisement for an international trans-Atlantic yacht race, and jumped at the opportunity for adventure. They were joined by the then US Vice-Consul to China, who was tasked with capturing the journey on film. Enduring typhoons and mishaps, the crew, having never sailed a century-old junk before, learned along the way. The crew included Reno Chen, Paul Chow, Loo-chi Hu, Benny Hsu, Calvin Mehlert and were led by skipper Marco Chung. After a journey of 6,000 miles (9,700 km), the Free China and her crew arrived in San Francisco Bay in fog on August 8, 1955. Shortly afterward the footage was featured on ABC television's Bold Journey travelogue. Hosted by John Stephenson and narrated by ship's navigator Paul Chow, the program highlighted the adventures and challenges of the junk's sailing across the Pacific, as well as some humorous moments aboard ship.[57]

In 1959 a group of Catalan men, led by Jose Maria Tey, sailed from Hong Kong to Barcelona on a junk named Rubia. After their successful journey this junk was anchored as a tourist attraction at one end of Barcelona harbor, close to where La Rambla meets the sea. Permanently moored along with it was a reproduction of Columbus' caravel Santa Maria during the 1960s and part of the 1970s.[58]

In 1981, Christoph Swoboda had a 65 feet (LoA) Bedar built by the boatyard of Che Ali bin Ngah on Duyong island in the estuary of the Terengganu river on the East coast of Malaysia. The Bedar is one of the two types of Malay junk schooners traditionally built there. He sailed this junk with his family and one friend to the Mediterranean and then continued with changing crew to finally finish a circumnavigation in 1998. He sold this vessel in 2000 and in 2004 he started to build a new junk in Duyong with the same craftsmen: the Pinas (or Pinis) Naga Pelangi, in order to help keep this ancient boat building tradition alive. This boat finished to be fitted out in 2010 and is working as a charter boat in the Andaman and the South China Sea.[59]

Notes

- Tanja sails, in the early European reports, are called lateen sail. Also, this type of sail may looked like triangular sail when sighted from afar.

- See definition of butt https://gizmodo.com/butt-is-an-actual-unit-of-measurement-1622427091. Until the 17th century, ton referred to both the unit of weight and the unit of volume - see https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/ton. A tun is 252 gallons, which weighs 2092 lbs, which is around a ton.

References

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle, Daniel R. Headrick, Steven W. Hirsch, Lyman L. Johnson, and David Northrup. "Song Dynasty." The Earth and Its Peoples. By Richard W. Bulliet. 4th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2008. 279–80. Print.

- Mudie, Rosemary; Mudie, Colin (1975), The history of the sailing ship, Arco Publishing Co., p. 152

- Real Academia Española (2020). "junco". «Diccionario de la lengua española» - Edición del Tricentenario (in Spanish). Retrieved 2020-04-13.

- Julia Jones The Salt-stained book, Golden Duck, 2011, p127

- Emma Helen Blair & James Alexander Robertson, ed. (1906). The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898.

- http://www.zdic.net/zd/zi/ZdicE8Zdic89Zdic9A.htm

- Manguin, Pierre-Yves (1993). "Trading Ships of the South China Sea. Shipbuilding Techniques and Their Role in the History of the Development of Asian Trade Networks". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 36 (3): 253–280.

- Zoetmulder, P. J. (1982). Old Javanese-English dictionary. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 9024761786.

- Reid, Anthony (2000). Charting the Shape of Early Modern Southeast Asia. Silkworm Books. ISBN 9747551063.

- "JONQUE : Etymologie de JONQUE". www.cnrtl.fr (in French). Retrieved 2018-03-30.

- Pham, Charlotte Minh-Hà L. (2012). "Unit 14: Asian Shipbuilding (Training Manual for the UNESCO Foundation Course on the protection and management of the Underwater Cultural Heritage)". Training Manual for the UNESCO Foundation Course on the Protection and Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage in Asia and the Pacificc. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-9223-414-0.

- Mahdi, Waruno (2007). Malay Words and Malay Things: Lexical Souvenirs from an Exotic Archipelago in German Publications Before 1700. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447054928.

- 'The Vanishing Jong: Insular Southeast Asian Fleets in Trade and War (Fifteenth to Seventeenth Centuries)', in Anthony Reid (ed.), Southeast Asia in the Early Modern Era (Ithaca: Cornell University Press), 197-213.

- Mahdi, Waruno (2007). Malay Words and Malay Things: Lexical Souvenirs from an Exotic Archipelago in German Publications Before 1700. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447054928.

- Smyth, Herbert W (1906). Mast and Sail in Europe and Asia. New York: E.P. Dutton. p. 397.

- Johnstone, Paul (1980). The Seacraft of Prehistory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 93–4. ISBN 978-0674795952.

- L. Pham, Charlotte Minh-Hà (2012). Asian Shipbuilding Technology. Bangkok: UNESCO Bangkok Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education. p. 20. ISBN 978-92-9223-413-3.

- Dix, President Dudley (2013-09-23). Shaped by Wind & Wave: Musings of a Boat Designer. Lulu Press, Inc. ISBN 9781105651120.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-12-01. Retrieved 2008-10-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) "The masts, hull and standing rigging" section, paragraph 2, retrieved 13 Aug 09.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-05-05. Retrieved 2009-08-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) "Materials and dimensions" section, paragraph 5, retrieved 13 Aug 09.

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 463.

- Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 469.

- Benjamin Franklin (1906). The writings of Benjamin Franklin. The Macmillan Company. pp. 148–149. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- The Oxford Handbook of Maritime Archaeology, p.185.

- Stephen Davies, On courses and course keeping in Ming Dynasty seafaring: probabilities and improbabilities, "Mapping Ming China's Maritime World", Hong Kong: Hong Kong Maritime Museum, 2015.

- Lawrence W. Mott, "The Development of the Rudder: A Technological Tale", College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1997.

- Konstam, Angus. 2007. Pirates: Predators of the Seas. 23-25

- Kang, Heejung (2015). "Kunlun and Kunlun Slaves as Buddhists in the Eyes of the Tang Chinese" (PDF). Kemanusiaan. 22 (1): 27–52.

- Dick-Read, Robert (2005). The Phantom Voyagers: Evidence of Indonesian Settlement in Africa in Ancient Times. Thurlton.

- "Strange Things of the South", Wan Chen, from Robert Temple

- Christie, Anthony (1957). "An Obscure Passage from the "Periplus: ΚΟΛΑΝΔΙΟϕΩΝΤΑ ΤΑ ΜΕΓΙΣΤΑ"". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 19: 345–353 – via JSTOR.

- Manguin, Pierre-Yves. 2012. “Asian ship-building traditions in the Indian Ocean at the dawn of European expansion”, in: Om Prakash and D. P. Chattopadhyaya (eds), History of science, philosophy, and culture in Indian Civilization, Volume III, part 7: The trading world of the Indian Ocean, 1500-1800, pp. 597-629. Delhi, Chennai, Chandigarh: Pearson.

- Rafiek, M. (December 2011). "Ships and Boats in the Story of King Banjar: Semantic Studies". Borneo Research Journal. 5: 187–200.

- Worcester, G. R. G. (1971). The Junks and Sampans of the Yangtze. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0870213350.

- Nugroho, Irawan Djoko (2011). Majapahit Peradaban Maritim. Jakarta: Suluh Nuswantara Bakti. ISBN 978-602-9346-00-8.

- https://books.google.ca/books?id=gUt7CgAAQBAJ&pg=PA238&dq=We+stopped+in+the+port+of+Calicut,+in+which+there+were+at+the+time+thirteen+Chinese+vessels,+and+disembarked.+On+the+China+Sea+traveling+is+done+in+Ch&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwic3aOBmpbrAhWFt54KHdCoD6MQuwUwAHoECAUQBw#v=onepage&q=We%20stopped%20in%20the%20port%20of%20Calicut%2C%20in%20which%20there%20were%20at%20the%20time%20thirteen%20Chinese%20vessels%2C%20and%20disembarked.%20On%20the%20China%20Sea%20traveling%20is%20done%20in%20Ch&f=false

- Heng, Derek (2019). "Ships, Shipwrecks, and Archaeological Recoveries as Sources of Southeast Asian History". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History: 1–29. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.97. ISBN 9780190277727.

- Dreyer 2007, p. 104.

- When China Ruled the Seas, Louise Levathes, p.80

- Sally K. Church: The Colossal Ships of Zheng He: Image or Reality ? (p.155-176) Zheng He; Images & Perceptions In: South China and Maritime Asia, Volume 15, Hrsg: Ptak, Roderich /Höllmann Thomas, O. Harrasowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden, (2005)

- Michel Munoz, Paul (2008). Early Kingdoms of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula. Continental Sales. pp. 396–397. ISBN 978-9814610117.

- Barbosa, Duarte (1866). A Description of the Coasts of East Africa and Malabar in the Beginning of the Sixteenth Century. The Hakluyt Society.

- Pires, Tome (1944). The Suma oriental of Tomé Pires : an account of the East, from the Red Sea to Japan, written in Malacca and India in 1512-1515 ; and, the book of Francisco Rodrigues, rutter of a voyage in the Red Sea, nautical rules, almanack and maps, written and drawn in the East before 1515. London: The Hakluyt Society. ISBN 9784000085052.

- Manguin, Pierre-Yves (September 1980). "The Southeast Asian Ship: An Historical Approach". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 11 (2): 266–276. doi:10.1017/S002246340000446X. JSTOR 20070359.

- Shaffer, Lynda Norene (1996). Maritime Southeast Asia to 1500. M.E. Sharpe.

- da Empoli, Giovanni (2010). Lettera di Giovanni da Empoli. California: Istituto Italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente.

- Albuquerque, Afonso de (1875). The Commentaries of the Great Afonso Dalboquerque, Second Viceroy of India, translated from the Portuguese edition of 1774. London: The Hakluyt society.

- Correia, Gaspar (1602). Lendas da Índia vol. 2. p. 219.

- Winstedt. A History of Malay. p. 70.

- Manguin, P.Y. (1980). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- R. H. Major, ed. (1857), "The travels of Niccolo Conti", India in the Fifteenth Century, Hakluyt Society, p. 27 Discussed in Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, p. 452

- Major, R. H., ed. (1857), "The travels of Niccolo Conti", India in the Fifteenth Century, Hakluyt Society, p. 27

- Fra Mauro map, 09-P25, original Italian: "Le naue ouer çonchi che nauegano questo mar portano quatro albori e, oltra de questi, do' che se può meter e leuar et ha da 40 in 60 camerele per i marchadanti e portano uno solo timon; le qual nauega sença bossolo, perché i portano uno astrologo el qual sta in alto e separato e con l'astrolabio in man dà ordene al nauegar" )

- Text from Fra Mauro map, 10-A13, original Italian: "Circa hi ani del Signor 1420 una naue ouer çoncho de india discorse per una trauersa per el mar de india a la uia de le isole de hi homeni e de le done de fuora dal cauo de diab e tra le isole uerde e le oscuritade a la uia de ponente e de garbin per 40 çornade, non trouando mai altro che aiere e aqua, e per suo arbitrio iscorse 2000 mia e declinata la fortuna i fece suo retorno in çorni 70 fina al sopradito cauo de diab. E acostandose la naue a le riue per suo bisogno, i marinari uedeno uno ouo de uno oselo nominato chrocho, el qual ouo era de la grandeça de una bota d'anfora."

- Robinson, Annie Maritime Maryport Dalesman 1978 p.31 ISBN 0852064802

- "E. Allen Petersen Dies at 84; Fled Japanese on Boat in '38". The New York Times. 14 June 1987.

- Charles W. Cushman Photograph Collection>> Results >> Details

- Jose Maria Tey, Hong Kong to Barcelona in the Junk "Rubia", George G. Harrap & Co. Ltd, London 1962

- 50 Years Malaysian-German Relations, Embassy of the Federal Republic of Germany, p132/133

Further reading

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China, Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Pirates and Junks in Late Imperial South China

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Junk (ship). |

- World of Boats (EISCA) Collection ~ Keying II Hong Kong Junk

- China Seas Voyaging Society

- The Free China, homepage of one of the last remaining 20th century junks, with video.

- The Junk and Advanced Cruising Rig Association, The JRA