Constitutional Assembly of Indonesia

The Constitutional Assembly (Indonesian: Konstituante) was a body elected in 1955 to draw up a permanent constitution for the Republic of Indonesia. It sat between 10 November 1956 and 2 July 1959. It was dissolved by then President Sukarno in a decree issued on 5 July 1959 which reimposed the 1945 Constitution.

Constitutional Assembly Konstituante | |

|---|---|

| Type | |

| Type | unicameral house |

| History | |

| Founded | 9 November 1956 |

| Disbanded | 5 July 1959 |

| Leadership | |

Chairman | |

Deputy Chairman | |

Deputy Chairman | |

Deputy Chairman | |

Deputy Chairman | |

Deputy Chairwoman | |

| Elections | |

First election | 15 December 1955 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Constitutional Assembly Building, Bandung | |

Background

On 17 August 1945, Sukarno proclaimed the independence of the Republic of Indonesia. The next day, a meeting of the Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence chaired by President Sukarno officially adopted the Constitution of Indonesia, which had been drawn up by the Investigating Committee for Preparatory Work for Independence in the months leading up to the Japanese surrender. In an speech, Sukarno stated that the constitution was "a temporary constitution...a lightning constitution", and that a more permanent version would be drawn up when circumstances permitted.[1]

It was not until 1949 that the Netherlands formally transferred sovereignty to Indonesia, and the United States of Indonesia was established. On 17 August the following year, this was dissolved and replaced by the unitary state of the Republic of Indonesia, with Sukarno at its head. Article 134 of the Provisional Constitution of 1950 stated, "The Constitutional Assembly together with the government shall enact as soon as possible the Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia which shall replace this Provisional Constitution."[2]

Organization

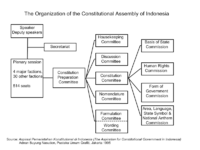

The supreme body within the assembly, with the authority to make decisions concerning the constitution and matters related to it was the plenary session. Other parts of the assembly were components of it and answered to it. It had to convene at least twice a year, and was obliged to meet if deemed necessary by the Constitution Preparation Committee at a written request from at least a tenth of the membership. Meetings had to be open to the public unless at least 20 members requested otherwise. There were 514 members, one per 150,000 Indonesian citizens. A two-thirds majority was required to approve a permanent constitution

The assembly was led by a speaker and five deputy speakers elected from the membership. The Constitution Preparation Committee represented all the groupings within the assembly, and was tasked with drawing up proposals for the constitution to be debated by the plenary session. Below this committee was the constitutional committee, which had the power to establish commissions made up of at least seven members according to need to discuss various aspects of the constitution, and other committees to discuss other specific issues.[2] [3]

Composition

Elections for the Constitutional Assembly were held in December 1955, but the assembly only convened in November 1956. There were a total of 514 members, with the composition broadly reflecting that of the People's Representative Council, the elections to which had produced very similar results. Like the legislature, no party had an overall majority, and the four largest parties were the Indonesian National Party (Partai Nasional Indonesia), the Masjumi, Nahdatul Ulama and the Indonesian Communist Party (Partai Komunis Indonesia). There were a total of 34 factions represented, divided into three blocs, according to the final form of the Indonesian state they wanted to see.[4]

| Faction | Seats |

|---|---|

| Pancasila Bloc (274 seats, 53.3%) | |

| Indonesian National Party (PNI) | 119 |

| Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) | 60 |

| Proclamation Republic | 20 |

| Indonesian Christian Party (Parkindo) | 16 |

| Catholic Party | 10 |

| Socialist Party of Indonesia (PSI) | 10 |

| League of Supporters of Indonesian Independence (IPKI) | 8 |

| Others | 31 |

| Islamic Bloc (230 seats, 44.8%) | |

| Masjumi | 112 |

| Nahdatul Ulama | 91 |

| Indonesian Islamic Union Party (PSII) | 16 |

| Islamic Educators Association (Perti) | 7 |

| Others | 4 |

| Socio-Economic Bloc (10 seats, 2.0%) | |

| Labour Party | 5 |

| Murba Party | 1 |

| Acoma Party | 1 |

| Total Seats | 514 |

Sessions

The Assembly met in the Gedung Merdeka in Bandung, which had been used for the 1955 Asian-African Conference. There were a total of four sessions.

10–26 November 1956

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Indonesia |

|

|

On 9 November 1956, the members elected to the Constitutional Assembly took their oaths of office, and the following day the Assembly was officially inaugurated by President Sukarno, who gave a speech a permanent constitution. Wilopo of the PNI was elected speaker, and Prawoto Manhkusasmito (Masjumi), with Fatchurahman Kafrawi (NU), Johannes Leimena (Parkindo), Sakirman (PKI) and Hidajat Ratu Aminah (IPKI) as deputy speakers.[3][5]

14 May – 7 December 1957

The session began with a discussion of procedures and regulations, then moved on to the material and system of constitution. However, the most important debate in this session was that on the basis of state. There were three proposals. Firstly, a state based on Pancasila, the philosophical basis for the state as formulated by Sukarno in a speech on 1 June 1945.[6] This was seen as a forum for all the different groups and beliefs in society that would be to the detriment of nobody. The second proposal was for a state based on Islam, and the third was for a socio-economic structure based on the family as set out in Article 33 of the 1945 Constitution. As none of the factions supporting these respective ideologies was able to command the necessary 2/3 of votes needed, this resulted in deadlock. Islamic parties accused the PKI of hypocrisy for supporting Pancasila with its commitment to belief in God rather than the socio-economic philosophy.[7]

Between 20 May and 13 June 1957, the Assembly discussed the material to be included in the debate over human rights. In contrast to the debate on the basis of the state, all sides were broadly in agreement over the importance of including provisions guaranteeing human rights in the new constitution, and this was subsequently agreed by acclamation.[8]

13 January – 11 September 1958

The most important business in the second session concerned human rights. From 28 January to 11 September 1958 there were 30 plenary sessions and a total of 133 speeches. Among the rights agreed on were freedom of religion, rights for women (including in marriage), the rights laid down in articles 16 and 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (the right to marriage and to raise a family, the right to health and prosperity and equal rights for children born outside marriage), the right to reasonable wage and freedom of the press.[9]

22 April – 2 June 1959

On 18 February 1959, the Constitution Preparation Committee decided the 1959 plenary session of the Assembly would begin on 29 April 1959 (subsequently brought forward a week) and would discuss the form of the state and government, the preamble to the constitution and the broad outlines of state policy. However, the following day, the cabinet decided to implement Sukarno's concept of Guided Democracy under the 1945 Constitution. Army Chief of Staff General Abdul Haris Nasution had first proposed a return to Indonesia's original constitution in August 1958. Although the PNI agreed to his proposal in early 1959, the NU leadership only did in the face of threats that pending corruption charges against party leaders would be taken to court, although the party membership was not consulted. The PKI followed suit once it realized the restoration of the constitution was inevitable. However Masjumi members were strongly opposed because of the potential to turn the nation into a dictatorship, as it would be very easy for the president to abuse his power. There were also calls for the human rights clauses agreed by the assembly to be included in the 1945 Constitution. Prime Minister Djuanda admitted there were shortcomings in the Constitution, but said that it could be amended at a later date. Meanwhile, the Army organized demonstrations in favor of the return to the 1945 Constitution. Sukarno left the country on a tour on 23 April, with the government confident of a two-thirds majority on the Assembly - sufficient to reintroduce the 1945 Constitution. However, the debate in the Assembly turned away from constitutional issues into the question of Islam, splitting the membership. The government tried to pressure the NU, but on 23 May, the proposal to include the Jakarta Charter was defeated in a plenary session of the Assembly and the NU turned against a return to the 1945 Constitution. At the first vote on 30 May, despite it being open to put pressure on NU members to follow the leadership's line, the vote was 269 in favor and 199 against - short of the two-thirds necessary. A secret ballot, allowing the NU members to change their votes without it being known, was held on 1 June, but also failed, as did a final open vote on 2 June, with just 56% in favor. The next day, 3 June 1959, the Assembly went into recess, never to meet again.[10][11][12]

The end of the Constitutional Assembly

Nasution wanted the Army to receive the credit for the restoration of the 1945 Constitution, and was behind the endeavor to find a mechanism to do so. A decree reimposing it could be justified by the current emergency situation, but the Constitutional Assembly also had to be removed from the scene. With the help of the League of Upholders of Indonesian Independence (IPKI), Nasution's solution was that if a majority of Assembly members refused to attend proceedings, it would automatically cease to exist. The IPKI therefore established a Front for the Defense of Pancasila, comprising 17 minor parties who would comply with this suggestion. The PKI and PNI subsequently said they would only attend to vote for the Assembly to be dissolved. On 15 June 1959, the Djuanda Cabinet contacted Sukarno overseas, advising him of possible plans of action, including issuing a decree. Two weeks later, Sukarno returned to Indonesia and decided to adopt this course of action. On 5 July 1959, two days after informing the cabinet of his decision, he issued a decree dissolving the Constituent Assembly and reimposing the 1945 Constitution.[13]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Constitutional Assembly of Indonesia. |

- Feith, Herbert (2007) The Decline of Constitutional Democracy in Indonesia Equinox Publishing (Asia) Pte Ltd, ISBN 978-979-3780-45-0

- Lev, Daniel S (2009) The Transition to Guided Democracy: Indonesian Politics 1957-1959 Equinox Publishing (Asia) Pte Ltd, ISBN 978-602-8397-40-7

- Nasution, Adnan Buyung (1995) Aspirasi Pemerintahan Konstitutional di Indonesia: Studi Sosio-Legal atas Konstituante 1956-1956 (Translation of The Aspiration for Constitutional Government in Indonesia: A Socio-Legal Study of the Indonesian Konstituante 1956-1959) Pustaka Utama Grafiti, Jakarta ISBN 979-444-384-4

- Republic of Indonesia Ministry of Information (1956) Provisional Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia Djakarta

- Ricklefs, M.C. (1991). A history of modern Indonesia since c.1200. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4480-7

- Saafroedin Bahar, Nannie Hudawati Sinaga, Ananda B.Kusuma et al. (Eds), (1992) Risalah Sidang Badan Penyelidik Usahah Persiapan Kemerdekaan Indonesian (BPUPKI) Panitia Persiapan Kemerdekaan Indonesia (PPKI) (Minutes of the Meetings of the Agency for Investigating Efforts for the Preparation of Indonesian Independence and the Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence), Sekretariat Negara Republik Indonesia, Jakarta ISBN 979-8300-00-9

Notes

- Saafroedin et al. (eds) (1992) p311-312

- Republic of Indonesia Ministry of Information (1956)

- Nasution (1995) pp. 37-39

- Nasution (1995) pp. 32-33,49

- Simorangkir & Mang Ray Sey (1958)

- Saafroedin et al. (eds) (1992) p63-69

- Nasution (1995) pp. 49-51

- Nasution (1995) pp. 134-135

- Nasution (1995) pp. 241-242

- Nasution (1995) pp. 318-402

- Ricklefs (1991) pp. 252-254

- Lev (2009) pp. 260-286

- Lev (2009) pp. 290-294