Kurdistan Region

The Kurdistan Region (KRI; Kurdish: هەرێمی كوردستان ,Herêma Kurdistanê,[12][13] Arabic: اقليم كوردستان[14]) is an autonomous region[15] in northern Iraq comprising the four Kurdish-majority populated governorates of Dohuk, Erbil, Halabja and Sulaymaniyah and bordering Iran, Syria and Turkey. The Kurdistan Region encompasses most of Iraqi Kurdistan but excludes the disputed territories of Northern Iraq, contested between the Kurdistan Regional Government and the central Iraqi government in Baghdad since Kurdish autonomy was realized in 1992 with the 1992 Iraqi Kurdistan parliamentary election in the aftermath of the Gulf War. The Kurdistan Region Parliament is situated in Erbil, but the constitution of the Kurdistan Region declares the disputed city of Kirkuk to be the capital of the Kurdistan Region. When the Iraqi Army withdrew from most of the disputed areas in mid-2014 because of the ISIL offensive in Northern Iraq, Kurdish Peshmerga entered the areas and held control there until October 2017.[16]

Kurdistan Region

| |

|---|---|

Coat of arms | |

| Anthem: "Ey Reqîb"[1] "Oh enemy" | |

.svg.png)

| |

| Autonomy founded | 19 May 1992[2] |

| Autonomy recognized | 15 October 2005[3] |

| Capital | Erbil (de facto), Kirkuk (de jure, under federal control)[2] 36°04′59″N 44°37′47″E |

| Official languages | Kurdish[2] |

| Administrative languages | Kurdish, Arabic[2] |

| Recognized languages | Arabic, Armenian, Assyrian Neo‑Aramaic, Turkmen[2][4] |

| Ethnic groups (2004[2]) | Recognized ethnicities: Kurds, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Arabs, Turkmens |

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) |

|

| Government | Parliamentary republic |

• President | Nechirvan Barzani |

• Prime Minister | Masrour Barzani |

• Deputy Prime Minister | Qubad Talabani |

| Legislature | 111-seat Kurdistan Parliament |

| Area | |

• Total | 41,220[8] km2 (15,920 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Estimate | 5,122,747 (2014)[9] |

| GDP (PPP) | 2015[10] estimate |

• Total | $26.5 billion[10] |

• Per capita | $7,000[10] |

| Gini (2012) | 32[11] medium |

| HDI | 0.750[11] high |

| Currency | Iraqi dinar |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (AST) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | 964 |

| Internet TLD | .krd |

The Kurds in Iraq oscillated between fighting for either autonomy or independence throughout the 20th century and experienced Arabization and genocide at the hands of Baathist Iraq.[17] However, the Iraqi no-fly zones over most of Iraqi Kurdistan after March 1991 gave the Kurds a chance to experiment with self-governance and the autonomous region was de facto established.[18] However, the Baghdad government only recognized the autonomy of the Kurdistan Region after the fall of Saddam Hussein, with a new Iraqi constitution in 2005.[19] A non-binding independence referendum was passed in September 2017, to mixed reactions internationally.

History

Early Kurdish struggle for autonomy (1923–1975)

Before Iraq became an independent state in 1923, the Kurds had already begun their independence struggle from the British Mandate of Iraq with the Mahmud Barzanji revolts which were subsequently crushed by the United Kingdom after a bombing campaign against Kurdish civilians by the Royal Air Force.[20][21] Nonetheless, the Kurdish struggle persisted and the Barzani tribe had by the early 1920s gained momentum for their nationalist beliefs and would become pivotal in the Kurdish-Iraqi wars throughout the 20th century. In 1943, the Barzani chief Mustafa Barzani began the Kurdish quest for autonomy[22] by raiding Iraqi police stations in Kurdistan which triggered Iraq to deploy 30,000 troops to the region and the Kurdish leadership had to flee to Iran in 1945. In Iran, Mustafa Barzani founded the Kurdistan Democratic Party and Iran and the Soviet Union began assisting the Kurdish rebels with arms.[23] Israel subsequently began assisting the Kurdish rebels by the early 1960s as well.[24]

From 1961 to 1970, the Kurds fought Iraq in the First Iraqi–Kurdish War which resulted in the Iraqi–Kurdish Autonomy Agreement but simultaneously with the promise of Kurdish autonomy, the Iraqi government began ethnic cleansing Kurdish populated areas to reduce the possible size of the autonomous entity which a census would determine.[17] This mistrust provoked the Second Iraqi–Kurdish War between 1974 and 1975 which ultimately resulted in a devastation for the Kurds (see Algiers Accord) and forced all rebels to flee to Iran.

Insurgency and first elections (1975–1992)

The more left-leaning Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) was founded in 1975 by Jalal Talabani and regenerated the Kurdish insurgency with guerrilla warfare tactics as the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) was slowly recovering from their defeat. However, the Kurdish insurgency became entangled in the Iran–Iraq War from 1980 onwards. During the first years of the war in the early 1980s, the Iraqi government tried to accommodate the Kurds in order to focus on the war against Iran. In 1983, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan agreed to cooperate with Baghdad, but the Kurdistan Democratic Party remained opposed.[29] In 1983, Saddam Hussein signed an autonomy agreement with Jalal Talabani of the PUK, though Saddam later reneged on the agreement.

By 1985, the PUK and KDP had joined forces, and Iraqi Kurdistan saw widespread guerrilla warfare up to the end of the war.[30] On 15 March 1988, PUK forces captured the town of Halabja near the Iranian border and inflicted heavy losses among Iraqi soldiers. The Iraqis retaliated the following day by chemically bombing the town, killing about 5,000 civilians.[31] This led the Americans and the Europeans to implement the Iraqi no-fly zones in March 1991 to protect the Kurds, thereby facilitating Kurdish autonomy amid the vacuum and the first Kurdish elections were consequently held in May 1992, wherein the Kurdistan Democratic Party secured 45.3% of the vote and a majority of seats.

Nascent autonomy, war and political turmoil (1992–2009)

The two parties agreed to form the first Kurdish cabinet led by PUK politician Fuad Masum as Prime Minister in July 1992 and the main focus of the new cabinet was to mitigate the effect of the American-led sanctions on Iraq and to prevent internal Kurdish skirmishes. Nonetheless, the cabinet broke down due to plagues of embattlement and technocracy which disenfranchised the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan and a new more partisan cabinet was formed and led by PUK politician Kosrat Rasul Ali in April 1993.[32] The KDP-PUK relations quickly deteriorated and the first clashes in the civil war took place in May 1994 when PUK captured the towns of Shaqlawa and Chamchamal from KDP, which in turn pushed PUK out of Salahaddin (near Erbil). In September 1998, the United States mediated a ceasefire and the two warring parties signed the Washington Agreement deal, where in it was stipulated that the two parties would agree on revenue-sharing, power-sharing and security arrangements.[33]

The anarchy in Kurdistan during the war created an opportunity for the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), which created bases in the northern mountainous areas of the Kurdistan Region,[34][35] which still plagues the Region in the 2010s with frequent calls for withdrawal.[36]

In advance of the Iraq war in 2003, the two parties united in the negotiations with the Arab opposition to Saddam Hussein and succeeded in harvesting political, economic, and security gains and the Arab opposition agreed to recognize Kurdish autonomy in the case that Saddam Hussein was removed from power.[37] America and Kurdistan also jointly rooted out the Islamist Ansar al-Islam group in Halabja area as Kurdistan hosted thousands of soldiers.[38][39] The Kurdish autonomy which had existed since 1992 was formally recognized by the new Iraqi government in 2005 in the new Iraqi constitution and the KDP- and PUK-administered areas reunified in 2006, making the Kurdistan Region into one single administration. This reunification prompted Kurdish leaders and the Kurdish President Masoud Barzani to focus on bringing the Kurdish areas outside of the Kurdistan Region into the region and building healthy institutions.[37]

In 2009, Kurdistan saw the birth of a new major party, the Gorran Movement, which was founded because of tensions in PUK and would subsequently weaken the party profoundly. The second most important political PUK figure, Nawshirwan Mustafa, was the founder of Gorran, who took advantage of sentiments among many PUK politicians critical of the cooperation with the KDP.[37] Gorran would subsequently win 25 seats (or 23.7% of the votes) in the 2009 parliamentary elections to the detriment of the Kurdistan List.[40] In the aftermath of the elections, Gorran failed at its attempts to persuade the Kurdistan Islamic Group and Kurdistan Islamic Union to leave the Kurdistan List, provoking both KDP and PUK. Gorran also attempted to create goodwill with the Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, which only aggravated the situation in Kurdistan, and the KDP and PUK chose to boycott Gorran from politics.[37]

ISIL and rapprochement with Iraq (after 2014)

In the period leading up to the ISIL invasion of Iraq in June 2014, the Iraqi-Kurdish relations were in a decline that the war against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) only worsened. When Iraqi forces withdrew from the Syrian-Iraqi border and away from the Disputed areas, the Kurdistan Region consequently had a 1,000 km front with ISIL, which put the region into an economic stalemate. However, Kurdistan did not compromise on their stance regarding financial independence from Baghdad.[41] Due to the Iraqi withdrawal, Kurdish Peshmerga took control of most disputed areas, including Kirkuk, Khanaqin, Jalawla, Bashiqa, Sinjar and Makhmur. The strategically important Mosul Dam was also captured by Kurdish forces.[16] However, the control was only temporary as Iraqi forces retook control over most of the disputed areas in October 2017, after the 2017 Kurdistan Region independence referendum.[42] As of 2019, the Kurdistan Region and the Federal Government in Baghdad are negotiating joint control over the disputed areas as their relations have become more cordial in the aftermath of ISIL's defeat.[43][44]

Government and politics

The Carnegie Middle East Center wrote in August 2015 that:[45]

The Kurdistan region of Iraq enjoys more stability, economic development, and political pluralism than the rest of the country. And public opinion under the Kurdistan Regional Government demands rule-of-law-based governance. But power is concentrated in the hands of the ruling parties and families, who perpetuate a nondemocratic, sultanistic system. These dynamics could foster instability in Kurdistan and its neighborhood, but could also provide a rare window of opportunity for democratization.

Administrative divisions

The Kurdistan Region is a democratic parliamentary republic and has a presidential system wherein the President is elected by Parliament for a five-year term.[2] The current President is Nechirvan Barzani who assumed office on 1 June 2019.[46] The Kurdistan Parliament has 111 seats and are held every fifth year.[2]

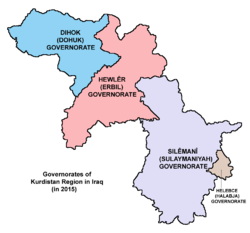

The Kurdistan Region is divided into four governorates: the governorates of Duhok, Erbil, Sulaymaniya and Halabja. Each of these governorates is divided into districts, for a total of 26 districts. Each district is also divided into sub-districts. Each governorate has a capital city, while districts and sub-districts have 'district centers'.[47]

Disputed areas

The Committee for implementing article 140 defines the disputed territories as those areas Arabised and whose border modified between 17 July 1968 and 9 April 2003. Those areas include parts of four governorates of pre-1968 borders.[48]

Disputed internal Kurdish–Iraqi boundaries have been a core concern for Arabs and Kurds, especially since US invasion and political restructuring in 2003. Kurds gained territory to the south of Iraqi Kurdistan after the US-led invasion in 2003 to regain what land they considered historically theirs.[49]

Foreign relations

Despite being landlocked, the Kurdistan Region pursues a proactive foreign policy, which includes strengthening diplomatic relations with Iran, Russia, United States and Turkey. 29 countries have a diplomatic presence in the Kurdistan Region, while the Kurdistan Region has representative offices in 14 countries.[50]

Economy

The Kurdistan Region has the lowest poverty rates in Iraq[52] and the stronger economy of the Kurdistan Region attracted around 20,000 workers from other parts of Iraq between 2003 and 2005.[53] The number of millionaires in the city of Sulaymaniyah grew from 12 to 2,000 in 2003, reflecting the economic growth.[54] According to some estimates, the debt of the Kurdish government reached $18 billion by January 2016.[55]

The economy of Kurdistan is dominated by the oil industry.[56] However, Kurdish officials have since the late 2010s attempted to diversify the economy to mitigate a new economic crisis like the one which hit the region during the fight against ISIL.[51] Major oil export partners include Israel, Italy, France and Greece.[57]

Petroleum and mineral resources

KRG-controlled parts of Iraqi Kurdistan contain 4 billion barrels of proven oil reserves. However, the KRG has estimated that the region contains around 45 billion barrels (7.2×109 m3) of unproven oil resource.[58][59][60][61] Extraction of these reserves began in 2007.

In November 2011, Exxon challenged the Iraqi central government's authority with the signing of oil and gas contracts for exploration rights to six parcels of land in Kurdistan, including one contract in the disputed territories, just east of the Kirkuk mega-field.[62] This act caused Baghdad to threaten to revoke Exxon's contract in its southern fields, most notably the West-Qurna Phase 1 project.[63] Exxon responded by announcing its intention to leave the West-Qurna project.[64]

As of July 2007, the Kurdish government solicited foreign companies to invest in 40 new oil sites, with the hope of increasing regional oil production over the following 5 years by a factor of five, to about 1 million barrels per day (160,000 m3/d).[65] Notable companies active in Kurdistan include Exxon, Total, Chevron, Talisman Energy, DNO, MOL Group, Genel Energy, Hunt Oil, Gulf Keystone Petroleum, and Marathon Oil.[66]

Other mineral resources that exist in significant quantities in the region include coal, copper, gold, iron, limestone (which is used to produce cement), marble, and zinc. The world's largest deposit of rock sulfur is located just southwest of Erbil.[67]

In July 2012, Turkey and the Kurdistan Regional Government signed an agreement by which Turkey will supply the KRG with refined petroleum products in exchange for crude oil. Crude deliveries are expected to occur on a regular basis.[68]

Demographics

Due to the absence of a proper census, the exact population and demographics of Kurdistan are unknown, but the Kurdistan has started to publish more detailed figures. The population of the region is notoriously difficult to ascertain, as the Iraqi government has historically sought to minimize the importance of the Kurdish minority while Kurdish groups have had a tendency to exaggerate the numbers.[69] Based on available data, Kurdistan has a young population with an estimated 36% of the population being under the age of 15.[70]

Ethnic data (1917–1947)

| Ethnic group |

British data 1917 | British data 1921 | British data 1930 | British data 1947 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Kurds | 401,000 | 54.4% | 454,720 | 57.9% | 393,000 | 55% | 804,240 | 63.1% |

| Arabs | – | – | 185,763 | 23.6% | – | – | – | – |

| Turkmens | – | – | 65,895 | 8.4% | – | – | – | – |

| Jews | – | – | 16,865 | 2.1% | – | – | – | – |

| Assyrians, Armenians | – | – | 62,225 | 7.9% | – | – | – | – |

| Other, unknown, not stated | 336,026 | 45.6% | – | – | 321,430 | 45% | 470,050 | 36.9% |

| Total | 737,026 | 785,468 | 714,430 | 1,274,290 | ||||

Religion

Kurdistan has a religiously diverse population. The dominant religion is Islam, which is professed by the majority of Kurdistan Region's inhabitants. These include Kurds, Iraqi Turkmen, and Arabs, belonging mostly to the Shafi'i school of Sunni Islam. There is also a small number of Shia Feyli Kurds,[72] as well as adherents of Sufi Islam.

In 2015, the Kurdistan Regional Government enacted a law to formally protect religious minorities. Christianity is professed by Assyrians and Armenians.

Yezidis make up a significant minority, with some 650,000 in 2005,[73] or 560,000 as of 2013,[72] The Shabaki and Yarsan (Ahl-e Haqq or Kakai) religions number around and 250,000 and 200,000 adherents respectively;[72] these, like Yezidism, are sometimes said to be related to the pre-Islamic indigenous religion of Kurdistan.[74]

The Zoroastrian religion have around 500 followers according to an official research from the religious affairs committee from the parliament.[75] Zoroastrians were seeking official recognition of their religion as of early 2016.[76] The first Zoroastrian temple was opened in the city of Sulaymaniyah (Silêmanî) in September 2016.[77]

A tiny ethno-religious community of Mandeans also exists within the semi-autonomous region. Kurdish Jews number some several hundred families in the autonomous region.[78]

Mudhafaria Minaret in the Minare Park, Erbil

Mudhafaria Minaret in the Minare Park, Erbil.jpg) Chaldean Catholic Mar Yousif Cathedral in Ankawa

Chaldean Catholic Mar Yousif Cathedral in Ankawa Jalil Al Khayat Mosque in Erbil

Jalil Al Khayat Mosque in Erbil Yazidi sites mark the tomb of Şêx Adî in Lalish

Yazidi sites mark the tomb of Şêx Adî in Lalish

Immigration

Widespread economic activity between Kurdistan and Turkey has given the opportunity for Kurds of Turkey to seek jobs in Kurdistan. A Kurdish newspaper based in the Kurdish capital estimates that around 50,000 Kurds from Turkey are now living in Kurdistan[79]

Refugees

The Kurdistan Region is hosting 1.2 million displaced Iraqis who have been displaced by the ISIS war, as of early December 2017. There were about 335,000 in the area prior to 2014 with the rest arriving in 2014 as a result of unrest in Syria and attacks by the Islamic State.[80]

Education

Before the establishment of the Kurdistan Regional Government, primary and secondary education was almost entirely taught in Arabic. Higher education was always taught in Arabic. This however changed with the establishment of the Kurdistan autonomous region. The first international school, the International School of Choueifat opened its branch in Kurdistan Region in 2006. Other international schools have opened and British International Schools in Kurdistan is the latest with a planned opening in Suleimaniah in September 2011.

Kurdistan Region's official universities are listed below, followed by their English acronym (if commonly used), internet domain, establishment date and latest data about the number of students.

| Institute | Internet domain | Established | Students |

|---|---|---|---|

| University of Sulaimani (UOS) | univsul.edu.iq | 1968 | 25,900 (2013) |

| Salahaddin University (SU) | www.su.edu.krd | 1970 | 20,000 (2013) |

| University of Dohuk | www.uod.ac | 1992 | 19,615 (2017)[81] |

| University of Zakho | www.uoz.edu.krd | 2010 | 2,600 (2011)[82] |

| University of Koya (KU) | www.koyauniversity.org | 2003 | 4260 (2014) |

| University of Kurdistan Hewler (UKH) | www.ukh.edu.krd | 2006 | 400 (2006) |

| The American University of Iraq – Sulaimani (AUIS) | www.auis.edu.krd | 2007 | 1100 (2014) |

| American University Duhok Kurdistan (AUDK) | www.audk.edu.krd | 2014 | |

| Hawler Medical University (HMU) | www.hmu.edu.krd | 2006 | (3400) (2018) |

| Business & Management University (BMU) | www.lfu.edu.krd/index.php | 2007 | |

| SABIS University | www.sabisuniversity.edu.iq | 2009 | |

| Cihan University | www.cihanuniversity.org | 2007 | |

| Komar University of Science and Technology (KUST) | www.komar.edu.iq | 2012 | |

| Hawler Private University for Science and Technology | hpust.com | ||

| Ishik University (IU) | www.ishik.edu.krd | 2008 | 1,700 (2012) |

| Soran University | www.soran.edu.iq | 2009 | 2200 (2011) |

| Newroz University | www.nawrozuniversity.com | 2004 | |

| University of Human Development (UHD/Qaradax) | www.uhd.edu.iq | 2008 | |

| Sulaimani Polytechnic University (SPU) | www.sulypun.org/sulypun | 1996 | 13000 (2013) |

Human rights

In 2010 Human Rights Watch reported that journalists in Kurdistan who criticize the regional government have faced substantial violence, threats, and lawsuits, and some have fled the country.[83] Some journalists faced trial and threats of imprisonment for their reports about corruption in the region.[83]

In 2009 Human Rights Watch found that some health providers in Iraqi Kurdistan had been involved in both performing and promoting misinformation about the practice of female genital mutilation. Girls and women receive conflicting and inaccurate messages from media campaigns and medical personnel on its consequences.[84] The Kurdistan parliament in 2008 passed a draft law outlawing the practice, but the ministerial decree necessary to implement it, expected in February 2009, was cancelled.[85] As reported to the Centre for Islamic Pluralism by the non-governmental organization, called as Stop FGM in Kurdistan, the Kurdistan Regional Government in northern Iraq, on 25 November, officially admitted the wide prevalence in the territory of female genital mutilation (FGM). Recognition by the KRG of the frequency of this custom among Kurds came during a conference program commemorating the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women.[86] On 27 November 2010, the Kurdish government officially admitted to violence against women in Kurdistan and began taking serious measures.[87] 21 June 2011 The Family Violence Bill was approved by the Kurdistan Parliament, it includes several provisions criminalizing the practice.[88] A 2011 Kurdish law criminalized FGM practice in Iraqi Kurdistan and law was accepted four years later.[89][90][91] The studies have shown that there is a trend of general decline of FGM.[92]

British lawmaker Robert Halfon sees Kurdistan as a more progressive Muslim region than the other Muslim countries in the Middle East.[93]

Although the Kurdish regional parliament has officially recognized ethnic minorities such as Assyrians, Turkmen, Arabs, Armenians, Mandeans, Shabaks and Yezidis, there have been accusations of Kurdish discrimination against those groups. The Assyrians have reported Kurdish officials' reluctance in rebuilding Assyrian villages in their region while constructing more settlements for the Kurds affected during the Anfal campaign.[94] After his visit to the region, the Dutch politician Joël Voordewind noted that the positions reserved for minorities in the Kurdish parliament were appointed by Kurds as the Assyrians for example had no possibility to nominate their own candidates.[95]

Assyrians have also accused the Kurdistan Regional Government of encouraging forced demographic change of villages that have been historically inhabited by native Assyrians.[96] This has been done through military land-grabs through the Peshmerga and financial incentives to encourage Kurdish citizens to inhabit those areas while encouraging Assyrians to flee. These land-grabs have led to a sharp decline in the Assyrian population of those areas, coincided with a drastic increase of the Kurdish population.[97][98][99][100]

The Kurdish regional government has also been accused of trying to Kurdify other regions such as the Nineveh plains and Kirkuk by providing financial support for Kurds who want to settle in those areas.[101][102] The KRG defend their actions as necessary compensation for the hundreds of thousands of Kurds that have been forced out of the same areas by previous Iraqi governments and during the Al-Anfal campaign.

In April 2016, Human Rights Watch wrote that the Kurdish security force of KRG, the Asayish, blocked the roads to Erbil to prevent Assyrians from holding a protest. According to demonstrators, the reason for the blocked protest was that Kurds in the Nahla Valley, mainly populated by Assyrians, encroached on land owned by Assyrians, without any action by courts or officials to remove the structures the Kurds built there.[103]

In February 2017, Human Rights Watch said Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) forces are detaining men and boys who have fled the fighting in Mosul even after they have passed security checks. Detainees were held for up to four months without any communication with their families. Relatives of these men and boys said that KRG and Iraqi forces didn't inform them of the places of their detained relatives and didn't facilitate any contact with them.[104]

Human Rights Watch reported that Kurdistan Regional Government security forces and local police detained 32 unarmed protesters in Erbil on March 4, 2017, at a peaceful demonstration against recent clashes in Sinjar. 23 of them were released at the same day and 3 more within four days, but 6, all foreign nationals, are still being held. A police chief ordered one protester who was released to permanently leave Erbil, where he was living. While in detention, protesters were not allowed to contact with anyone or have access to a lawyer.[105]

In 2017, Assyrian activists Juliana Taimoorazy and Matthew Joseph accused the Kurdistan Regional Government of issuing threats of violence against Assyrians living in the area who protested its independence referendum. These accusations were later confirmed when the KDP-controlled provincial council of Alqosh issued a statement warning residents that they would face consequences for protesting the referendum.[106]

In 2010, it was reported that passing of a new law in Iraqi Kurdistan, guaranteeing “gender equality”, has deeply outraged some local religious community, including the minister of endowments and religious affairs and prominent imams, who interpreted the phrase as "legitimizing homosexuality in Kurdistan".[107] Kamil Haji Ali, the minister of endowments and religious affairs, said in this regard that the new law would “spread immorality” and “distort” Kurdish society.[107] Following an outrage of religious movements, the KRG held a press conference, where the public were ensured that gender equality did not include giving marriage rights to homosexuals, whose existence is effectively invisible in Iraq due to restrictive traditional rules.[107]

In the disputed areas of Sinjar and the Nineveh Plains, the Kurdistan Regional Government has been accused by the native Assyrian[96][108] and Yazidi[109][110] inhabitants of forcefully disarming them with the guarantee of protection in order to justify the Peshmerga’s presence in those regions.[109] In 2014, when the Islamic State invaded Northern Iraq, the Peshmerga abandoned their posts in these areas without notifying the locals, who had been disarmed and guaranteed protection by them.[110] This contributed to the quick invasion of the area by ISIS and the massacre and displacement of the native Assyrians and Yazidis who were rendered defenseless by their forced disarmament.[111][109]

Infrastructure and transport

Infrastructure

Due to the devastation of the campaigns of the Iraqi army under Saddam Hussein and other former Iraqi regimes, the Kurdistan Region's infrastructure was never able to modernize. After the 1991 safe haven was established, the Kurdistan Regional Government began projects to reconstruct the Kurdistan Region. Since then, of all the 4,500 villages that were destroyed by Saddam Husseins' regime, 65% have been reconstructed by the KRG.[112]

Mobility

Iraqi Kurdistan can be reached by land and air. By land, Iraqi Kurdistan can be reached most easily by Turkey through the Habur Border Gate which is the only border gate between Iraqi Kurdistan and Turkey. This border gate can be reached by bus or taxi from airports in Turkey as close as the Mardin or Diyarbakir airports, as well as from Istanbul or Ankara. Iraqi Kurdistan has two border gates with Iran, the Haji Omaran border gate and the Bashmeg border gate near the city of Sulaymaniyah. Iraqi Kurdistan has also a border gate with Syria known as the Faysh Khabur border gate.[113] From within Iraq, the Kurdistan Region can be reached by land from multiple roads.

Iraqi Kurdistan has opened its doors to the world by opening two international airports. Erbil International Airport and Sulaimaniyah International Airport, which both operate flights to Middle Eastern and European destinations. The KRG spent millions of dollars on the airports to attract international carriers, and currently Turkish Airlines, Austrian Airlines, Lufthansa, Etihad, Royal Jordanian, Emirates, Gulf Air, Middle East Airlines, Atlas Jet, and Fly Dubai all service the region. There are at least 2 military airfields in Iraqi Kurdistan.[114]

References

- "Flag and National Anthem". Government of Kurdistan Region. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- "Kurdistan: Constitution of the Iraqi Kurdistan Region". 14 April 2004. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- Joseph R. Rudolph Jr. (2015). Encyclopedia of Modern Ethnic Conflicts, 2nd Edition. p. 275.

- "A Reading for the Law of Protecting Components in Kurdistan" (PDF). July 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for (2 September 2016). "Iraq: Information on the treatment of atheists and apostates by society and authorities in Erbil; state protection available (2013-September 2016)". Refworld. Canada: Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Kurdistan, the only government in Middle East that recognizes religious diversity". Kurdistan24. 10 April 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Country Information and Guidance Iraq: Religious minorities" (PDF). Government of the United Kingdom. August 2016: 13. Retrieved 31 August 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Almas Heshmati, Nabaz T. Khayyat (2012). Socio-Economic Impacts of Landmines in Southern Kurdistan. p. 27.

- "Demographic Survey - Kurdistan Region of Iraq" (PDF). Relief Web. July 2018. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- "Erbil International Fair" (PDF). aiti.org.ir. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- "Iraq Human Development Report 2014" (PDF). p. 29. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- "حکومەتی هەرێمی كوردستان" (in Kurdish). Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- "Şandeke Herêma Kurdistanê serdana Bexdayê dike". Rûdaw (in Kurdish). Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- "حكومة اقليم كوردستان" (in Arabic). Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- "Iraq's Constitution of 2005" (PDF). 2005. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Iraqi Kurds 'withdraw to 2014 lines'". 18 October 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Alex Danilovich (2016). Iraqi Kurdistan in Middle Eastern politics. p. 18. ISBN 978-1315468402.

- Peter J. Lambert (December 1997). The United States and the Kurds: case studies in United States engagement (PDF). Monterey, California: Calhoun - Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School. pp. 85–87. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Philip S. Hadji (September 2015). "Iraq Timeline: Since the 2003 War". United States Institute of Peace. 41 (2). Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Mari R. Rostami (2019). Kurdish Nationalism on Stage: Performance, Politics and Resistance in Iraq. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 67. ISBN 978-1788318709.

- E. O'Ballance (1995). The Kurdish Struggle, 1920-94. Palgrave. p. 20.

- Tareq Y. Ismael, Jacqueline S. Ismael (2005). Iraq in the Twenty-First Century: Regime Change and the Making of a Failed State. Routledge. p. 28. ISBN 1317567595.

- Gordon W. Rudd (2004). Humanitarian Intervention - Assisting the Iraqi Kurds in Operation PROVIDE COMFORT, 1991. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Army. p. 12.

- Arash Reisinezhad (2018). The Shah of Iran, the Iraqi Kurds, and the Lebanese Shia. p. 126. ISBN 978-3319899473.

- Rafaat, Aram (2018). Kurdistan in Iraq: The Evolution of a Quasi-State. Routledge. p. 170. ISBN 9781351188814.

- Howard, Michael (6 February 2008). "New Iraqi flag hailed as symbolic break with past". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- "Absence of Iraqi flag on Talabani's casket in ceremony was unintentional: PUK official". Kurdistan24. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- "Foreign Ministry of Jordan: put the flag of the Kurdistan region instead of the Iraqi flag during the reception of Barzani error protocol". Iraqi News Agency (in Arabic). Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- Katzman, Kenneth (1 October 2010). "The Kurds in Post-Saddam Iraq" (PDF). Congressional Research Service: 2. Retrieved 2 August 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Efraim Karsh (2002). The Iran-Iraq War, 1980-1988. Osprey Pub. ISBN 978-1-84176-371-2.

- David McDowall (2004). A modern history of the Kurds (3rd ed.). I.B. Tauris. p. 357. ISBN 9781850434160.

- Gareth R. V. Stansfield (2003). Iraqi Kurdistan - Political development and emergent democracy. pp. 146–152. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.465.8736. ISBN 0-415-30278-1.

- Alan Makovsky (29 September 1998). "Kurdish Agreement Signals New U.S. Commitment". Washington Institute. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Robert W. Olson (1996). The Kurdish nationalist movement in the 1990s: its impact on Turkey and the Middle East. p. 56.

- Kanan Makiya (1998). Republic of Fear: The Politics of Modern Iraq, Updated Edition. University of California Press. p. 321. ISBN 0520921240.

- "Barzani: PKK Rebels Should Leave Northern Iraq". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. 1 August 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Mohammed M. A. Ahmed (2012). Iraqi Kurds and nation-building (1st ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781137034076.

- Krajeski, Jenna (20 March 2013). "The Iraq War Was a Good Idea, If You Ask the Kurds". The Atlantic. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Appendix B – Statement of Reasons – Ansar al-Islam (formerly Ansar al-Sunna). Parliament of Australia. 15 June 2009. ISBN 978-0-642-79186-3.

- "Kurdish opposition makes strong showing in Iraq regional elections". Los Angeles Times. 27 July 2009. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Aram Rafaat (2018). Kurdistan in Iraq: The Evolution of a Quasi-State. Routledge. p. 187. ISBN 9780815393337.

- "Infographic: Control Over Iraq's Disputed Territories". Stratfor. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Kurdish leaders discuss disputed areas, Erbil-Baghdad ties with US delegation". Kurdistan24. 25 June 2019. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Exclusive: New Kurdish PM says priority is stronger Baghdad ties, rather than independence". Reuters. 10 July 2019. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Kurdistan's Politicized Society Confronts a Sultanistic System". Carnegie Middle East Center. 2015-08-18. Archived from the original on 2016-06-08. Retrieved 2016-06-08.

- "Nechirvan Barzani elected president of Kurdistan Region of Iraq". Reuters. 28 May 2019. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Map of area of Kurdistan Region & its Governorates". www.krso.net. Archived from the original on 2016-01-19. Retrieved 2016-01-17.

- "نبذة عن اللجنة". com140.com. p. ar. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Bartu, Peter (2010). "Wrestling With the Integrity of A Nation: The Disputed Internal Boundaries in Iraq". International Affairs. 6. 86 (6): 1329–1343. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2346.2010.00946.x.

- "Department of Foreign Relations Kurdistan Regional Government". dfr.gov.krd. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Pankaj, D.; Ramyar, R.A. (22 January 2019). "Diversification Of Economy–An Insight into Economic Development with Special Reference to Kurdistan" s Oil Economy and Agriculture Economy". Russian Journal of Agricultural and Socio-Economic Sciences. 85 (1): 395–404. doi:10.18551/rjoas.2019-01.48.

- "Nearly 25 percent of Iraqis live in poverty". NBC News. 2009-05-20. Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- Barkey, HJ; Laipson, E (2005). "Iraqi Kurds And Iraq's Future". Middle East Policy. 12 (4): 66–76 [68]. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4967.2005.00225.x.

- "Iraqi President Talabani's Letter to America". 22 September 2006. Archived from the original on 15 February 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Zaman, Amberin (20 January 2016). "Is the KRG heading for bankruptcy?". Al-Monitor. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "The Kurdish opening". The Economist. 2012-11-03. Archived from the original on 2017-09-23. Retrieved 2017-09-01.

- "Israel turns to Kurds for three-quarters of its oil supplies". Financial Times. 23 August 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- U.S. Energy Information Administration Archived 2014-12-23 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2014-12-23.

- Bloomberg Archived 2015-01-11 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2014-12-23.

- New oil pipeline boosts Iraqi Kurdistan Archived 2017-10-12 at the Wayback Machine, Washingtonpost. Retrieved 2014-12-23

- Will Kurds use oil to break free from Iraq? Archived 2014-09-14 at the Wayback Machine, CNN. Retrieved 2014-12-23

- "westernzagros.com Oil Map" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-09.

- "Exxon's Kurdistan". Zawya. 3 April 2012. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014.

- "Iraq says expects Exxon to finish West Qurna Sale by December". Reuters.

- "Iraqi Kurds open 40 new oil sites to foreign investors". Iraq Updates. 2007-07-09. Archived from the original on 2011-04-24. Retrieved 2011-05-13.

- "Kurdistan Oil and Gas Activity Map" (PDF). Western Zagros. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-09. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- Official statements on the oil and gas sector in the Kurdistan region Archived 2007-10-12 at the Wayback Machine, Kurdistan Development Corporation.

- "First Shipment of Kurdistan Crude Arrives in Turkey". BrightWire. Archived from the original on 2013-01-18.

- Gareth R. V. Stansfield; Jomo (29 August 2003). Iraqi Kurdistan: Political Development and Emergent Democracy. Routledge. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-1-134-41416-1. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- "The people of the Kurdistan Region". www.krg.org. Archived from the original on 2012-11-06. Retrieved 2012-11-19.

- Fuat Dundar (2012). "British Use of Statistics in the Iraqi Kurdish Question (1919–1932)" (PDF): 45. Retrieved 12 November 2019. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Minorities in Iraq: Memory, Identity and Challenges" (PDF). 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 1, 2014.

- "Iraq's Yezidis: A Religious and Ethnic Minority Group Faces Repression and Assimilation" (PDF). September 25, 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 9, 2006.

- Izady, Mehrdad R. (1992). The Kurds: a concise handbook, p. 170.

- "پەرلەمانی كوردستان ئەمڕۆ كۆدەبێتەوە". February 12, 2018. Archived from the original on February 13, 2018. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- "Zoroastrianism in Iraq seeks official recognition". Al-Monitor. 2016-02-17. Archived from the original on 2017-04-08. Retrieved 2016-05-16.

- "Hopes for Zoroastrianism revival in Kurdistan as first temple opens its doors". rudaw.net. 21 September 2016. Archived from the original on 7 February 2018. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- Sokol, Sam (18 October 2015). "Jew appointed to official position in Iraqi Kurdistan". Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- "An unusual new friendship". The Economist. February 19, 2009. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved May 25, 2009.

- "Urgent reconstruction needed for returning Iraqi refugees: IOM". Rudaw. February 22, 2018. Archived from the original on February 22, 2018. Retrieved February 22, 2018.

- "About The University of Dohuk". Archived from the original on 2017-11-17. Retrieved 2017-11-16.

- "Opening Ceremony of The 1st International Scientific Conference – UOZ 2013". Archived from the original on 2014-12-05. Retrieved 2014-11-27.

- "Iraqi Kurdistan: Journalists Under Threat". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 18 August 2014. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- "Abusing Patients | Human Rights Watch (Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) section)". Archived from the original on 2011-03-08. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- "Iraq". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 20 May 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- "IRAQ: Iraqi Kurdistan Confronts Female Genital Mutilation". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- Rudaw in English The Happening: Latest News and Multimedia about Kurdistan, Iraq and the World – Kurdistan Takes Measures Against Gender-Based Violence Archived 2011-09-02 at the Wayback Machine

- "Human Rights Watch lauds FGM law in Iraqi Kurdistan". Ekurd.net. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- "KRG looks to enhance protection of women, children". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- "Human Rights Watch lauds FGM law in Iraqi Kurdistan". Ekurd.net. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- Iraqi Kurdistan: Law Banning FGM Not Being Enforced Archived 2017-04-09 at the Wayback Machine Human Rights Watch, August 29, 2012

- "Stop FGM in Kurdistan". www.stopfgmkurdistan.org. Archived from the original on 2016-01-23. Retrieved 2016-01-25.

- "British MP hails Iraqi Kurdistan as regional leader in religioustolerance". Ekurd.net. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- Al-Ali, Nadje; Pratt, Nicola (2009). What kind of liberation?: women and the occupation of Iraq. University of California Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-520-25729-0. Archived from the original on 2016-01-07. Retrieved 2015-10-12.

- Voordewind, Joël (2008). Religious Cleansing in Iraq (PDF). nowords, ChristenUnie. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-04-11.

- Hanna, Reine (June 1, 2020). "Contested Control: The Future of Security in Iraq's Nineveh Plain" (PDF). Assyrian Policy Institute. p. 24. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- Davis, Taiyo (December 4, 2019). "Kurdish Tribes Stealing Assyrian Christian Lands". Foreign Policy Journal. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Benjamen, Alda (September 29, 2017). "Minorities and the Kurdish Referendum". University of Chicago Center for Middle Eastern Studies. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- In the shadow of the war on ISIS: Thefts & confiscations of Assyrian lands and villages by the KRG on YouTube

- Kurds taking over Assyrian lands with English subtitles on YouTube

- Hashim, Ahmed (2005). Insurgency and counter-insurgency in Iraq. Cornell University Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-8014-4452-4. Archived from the original on 2016-01-07. Retrieved 2015-10-12.

- Taneja, Preti (2007). Assimilation, exodus, eradication: Iraq's minority communities since 2003. Minority Rights Group International. p. 20. Archived from the original on 2016-01-07. Retrieved 2015-10-12.

- "Iraqi Kurdistan: Christian Demonstration Blocked". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- "Iraq/Kurdistan Region: Men, Boys Who Fled ISIS Detained". Human Rights Watch. 2017-02-26. Archived from the original on 2017-03-01. Retrieved 2017-02-28.

- "Kurdistan Region of Iraq: 32 Arrested at Peaceful Protest". Human Rights Watch. 2017-03-16. Archived from the original on 2017-03-24. Retrieved 2017-03-23.

- Smith, Jesserer (October 3, 2017). "Kurdish Referendum May Imperil Christian and Minority Safe Haven in Iraq". National Catholic Register. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- Homosexuality Fears Over Gender Equality in Iraqi Kurdistan Archived 2012-01-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Hanna, Reine (September 26, 2019). "Testimony for the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom Religious Minorities' Fight to Remain in Iraq" (PDF). United States Commission on International Religious Freedom. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ""They came to destroy": ISIS Crimes Against the Yazidis" (PDF). June 15, 2016. p. 6. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- van den Toorn, Christine (August 17, 2014). "How the U.S.-Favored Kurds Abandoned the Yazidis when ISIS Attacked". Institute of Regional & International Studies. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- Assyrians Disarmed and Abandoned to ISIS by Kurdish Peshmerga on YouTube

- "Kurdistan Regional Government". KRG. Archived from the original on 2014-04-05. Retrieved 2014-05-04.

- "Iraq federal, Kurd region oil chiefs informally agree on exports". UPI.com. Archived from the original on 2013-11-10. Retrieved 2010-12-28.

- "Military Comms Monitoring. HF VHF UHF". Milaircomms.com. Archived from the original on 2012-09-13. Retrieved 2010-12-28.