British nationality law and Hong Kong

British nationality law as it pertains to Hong Kong has been unusual ever since Hong Kong became a British colony in 1842. From its beginning as a sparsely populated trading port to today's cosmopolitan international financial centre and world city of over seven million people, the territory has attracted refugees, immigrants and expatriates alike searching for a new life.

| British citizenship and nationality law |

|---|

|

| Introduction |

| Nationality classes |

|

| See also |

| Relevant legislation |

Citizenship matters were complicated by the fact that British nationality law treated those born in Hong Kong as British subjects (although they did not enjoy full rights and citizenship), while the People's Republic of China did not recognise Hong Kongers with Chinese ancestry as British. The main legal rationale for the Chinese position was that recognising these people as British could be seen as tacit acceptance of a series of treaties which China considers "unequal" – including the ones which ceded the Hong Kong Island, the Kowloon Peninsula and the land between the Kowloon Peninsula and the Sham Chun River and neighbouring islands (i.e. the New Territories) to the UK. The main political reason was to prevent the vast majority of Hong Kong residents from having any recourse to British assistance (e.g. by claiming consular assistance or protection under an external treaty) after the handover of Hong Kong.

Early colonial era

English common law has the rationale of natural-born citizenship, following the principle of jus soli, in the theory that people born within the dominion of The Crown, which included self-governing dominions and Crown colonies, would have a "natural allegiance" to the Crown as a "debt of gratitude" to the Crown for protecting them through infancy. As the dominion of the British Empire expanded, British subjects included not only persons within the United Kingdom but also those throughout the rest of the British Empire.

By this definition, anyone born in Hong Kong after it became a British colony in 1842 was a British subject. The Naturalisation of Aliens Act 1847 expanded what had been covered in the Naturalisation Act 1844, which applied only to people within the United Kingdom, to all its dominions and colonies. The Act made provisions for naturalisation as well as allowing for acquisition of British subject status by marriage between a foreign woman and a man with British subject status.

British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act 1914

The British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act 1914 (now renamed as "Status of Aliens Act 1914") came into force on 1 January 1915, codifying for the first time the law relating to British nationality. No major change was introduced but it set into law how people associated with Hong Kong – as part of "His Majesty's dominions" – would acquire British subject status.

British Nationality Act 1948

The Commonwealth of Nations' heads of government decided in 1948 to embark on a major change in the law of nationality throughout the Commonwealth. It was decided at the conference that the United Kingdom and the self-governing dominions would each adopt separate national citizenship, but retain the common imperial status of British subject. The British Nationality Act 1948 provided for a new status of Citizen of the United Kingdom and Colonies (CUKC), consisting of British subjects who had a close relationship (either through birth or descent) with the United Kingdom and its remaining colonies. The Act also provided that British subjects could be known by the alternative title Commonwealth citizen.

The Act came into force on 1 January 1949 and stipulated that anyone born in "United Kingdom or a colony" on or after that date was a CUKC. Those who were British subjects on 31 December 1948 were entitled to acquire CUKC status by declaration. The deadline for this was originally 31 December 1949, but the deadline was extended to 31 December 1962 by the British Nationality Act 1958.

British Nationality Acts were passed in 1958, 1964 and 1965, which mainly fine-tuned special provisions about CUKC status acquisition.

Commonwealth Immigrants Acts

Until 1962, all Commonwealth citizens could enter and stay in the United Kingdom without any restriction. Anticipating immigration waves from former and current colonies in Africa and Asia with the decolonisation of the 1960s, the United Kingdom passed the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962 and Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1968 to tighten immigration control for CUKCs into the United Kingdom.

As such, CUKCs connected with Hong Kong were subject to immigration control after 1962.

Finally, under the Immigration Act 1971, the concept of patriality or right of abode was created. CUKCs and other Commonwealth citizens had the right of abode in the UK only if they, their husband (if female), their parents or their grandparents were connected with the United Kingdom. This placed the UK in the rare position of denying some of its nationals entry into their country of nationality. However, the concept of patriality was only a temporary solution to halt a sudden wave of migration. The British government later reformed the law, resulting in the British Nationality Act 1981.

These acts shaped an increasingly restrictive immigration policy into the UK for Hong Kong residents even before the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984.

British Nationality Act 1981 and British Dependent Territories Citizenship

The British Nationality Act 1981 created new categories of British nationality and renamed British colonial territories. After implementation, all British Crown colonies became British Dependent Territories. The Act abolished the status of CUKC, and replaced it with three new categories of nationality on 1 January 1983:

- British Citizen (for residents of the UK and the Crown dependencies)

- British Dependent Territories Citizen (BDTC) (for the Crown colonies), and

- British Overseas Citizen (BOC) (a class of non-inheritable nationality for those who are unable to become a British Citizen, a BDTC or a national of another country)

The law stated that those who have CUKC status by connection with Hong Kong and those born in Hong Kong on or after 1983 to a parent settled in Hong Kong are BDTCs. The law also stated that British Citizens or BDTCs by descent could not automatically pass on British nationality to a child born outside the United Kingdom or the dependent territories concerned unless a parent acquired citizenship otherwise than by descent.

After the Sino-British Joint Declaration

.svg.png)

Negotiation concerning the future of Hong Kong started in the late 1970s between Britain and China. With the signing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration on 19 December 1984, the future of Hong Kong was set, with China to assume sovereignty of the entire territory of Hong Kong on 1 July 1997.

At that time, there were some 3.5 million residents of Hong Kong with BDTC status by virtue of their connection with Hong Kong. Another 2 million were believed to have been eligible to apply to become BDTCs. After the handover, they would have lost this status and became solely Chinese nationals. At the time, Hong Kong was the largest of the remaining British dependent territories with over 5 million inhabitants.

Creation of the British National (Overseas) status

| Demographics and culture of Hong Kong |

|---|

| Demographics |

|

| Culture |

| Other Hong Kong topics |

The Hong Kong Act 1985 created an additional category of British nationality known as British National (Overseas) or BN(O). This new category was available only to Hong Kong BDTCs, and any Hong Kong BDTC who wished to do so would be able to acquire the status of BN(O). The status was non-transferable and available only by application, and the deadline to apply was 30 June 1997.

British Overseas Citizen status for those who are 'otherwise stateless'

Any Hong Kong BDTCs who failed to register as a BN(O) by 1 July 1997 and would thereby be rendered stateless (generally because they were a non-ethnic Chinese and therefore could not automatically acquire Chinese nationality), automatically became a British Overseas Citizen under the Hong Kong (British Nationality) Order 1986.[1]

British Nationality (Hong Kong) Act 1990: British citizenship for 50,000 Hong Kong families

After the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989, many people in Hong Kong began to fear for their future post-1997. Emigration was rampant and a brain-drain was beginning to affect the economy of Hong Kong. To stem the drain, people urged the British government to grant full British citizenship to all Hong Kong BDTCs – but this request was never accepted. However, the British did agree to creating the British Nationality Selection Scheme, which granted to a select 50,000 people and their families the ability to obtain full British citizenship without having to fulfill the ordinary requirements, under the British Nationality (Hong Kong) Act 1990.[2] Under the Act, the Home Secretary was required to register any person recommended by the Governor of Hong Kong (as well as the applicant's spouse and minor children) as a British Citizen. Any person who was registered under the act automatically ceased to be a BDTC upon registration as a British Citizen. No person could be registered under the act after 30 June 1997.

Hong Kong (War Wives and Widows) Act 1996: British citizenship for Hong Kong war wives and widows

Women who had received assurance from the Secretary of State that they would be eligible for settlement in the United Kingdom on the basis of their husband's war service in the defence of Hong Kong may be registered as British Citizens if they were resident in Hong Kong and had not remarried. There is no requirement for the woman to hold (or have held) any form of British nationality. Women registered as British Citizens under this act acquire British citizenship "otherwise than by descent" and thus also their children would be British Citizens.[3]

British Nationality (Hong Kong) Act 1997: British citizenship for British Nationals (Overseas) without Chinese ancestry

Another special group of solely Hong Kong British nationals were the non-Chinese ethnic minorities of Hong Kong. They are primarily immigrants or children of immigrants from Nepal, India and Pakistan. After the handover to China, they would not be accepted as inherently being citizens of the People's Republic. They would be left effectively stateless – they would have British nationality and permanent residency and right of abode in Hong Kong, but no right of abode in the UK, nor a right to claim Chinese nationality.

The ethnic minorities petitioned to be granted full British citizenship,[4] and were backed by several politicians Jack Straw, then the Shadow Home Secretary said [5] in a letter to the then Home Secretary Michael Howard dated 30 January 1997 that "common sense and common humanity demand that we give these people full British citizenship. The limbo in which they will find themselves in July arises directly from the agreements which Britain made with China". He further stated that a claim that BN(O) status amounts to British nationality "is pure sophistry".</ref> and media.[6] The subsequently enacted British Nationality (Hong Kong) Act 1997[7] gives them an entitlement to acquire full British citizenship by making an application to register for that status after 1 July 1997.

Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002: British Overseas Territories Citizen status is not applicable to Hong Kong

In light of the passing of the British Overseas Territories Act 2002, which made provision to substitute the wording of "British Dependent Territories" with "British Overseas Territories" in the British Nationality Act 1981 among other new provisions, further clarification was made even though this act did not even apply to Hong Kong. Section 14 of the subsequent Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 stated specifically that a person may not be registered as a British Overseas Territories Citizen (BOTC) by virtue of a connection with Hong Kong.

Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act 2009: British citizenship for British Nationals (Overseas) who do not have another nationality or citizenship

A small group of Hong Kong ethnic minorities had not been eligible for acquiring British citizenship under the British Nationality (Hong Kong) Act 1997 because they were not ordinarily resident in Hong Kong before 4 February 1997 or they were under 18 / 21 years of age, had dual nationality through their parents on or after 4 February 1997, but had lost it upon turning 18/21.[8] These BN(O)s lost their second nationality due to changes in the nationality laws of certain countries and had, therefore, become de facto stateless. They could register to become British citizens under section 4B of the British Nationality Act 1981 as amended by Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act 2009 to "remedy the limbo status of probably the last remaining group of solely British nationals who have no other nationality or citizenship, who have not recently and deliberately given up another nationality or citizenship".[9] To be eligible for registration, they must demonstrate that they had not lost, through action or inaction, any other nationality on and after 19 March 2009.[10] Registration under s4B confers British citizenship by descent.

Chinese view on nationality of Hong Kong residents

The Chinese government stated in its memorandum of the Sino-British Joint Declaration on December 19, 1984 that under the Chinese nationality law, "all Hong Kong Chinese compatriots, whether they are holders of the 'British Dependent Territories Citizens' Passport' or not, are Chinese nationals".[11] In 1990, when the Gulf War started, the Chinese embassy provided a proof of Chinese citizenship to a Hong Kong Chinese businessman in Kuwait holding a BDTC passport and helped him evacuate.[12] Chinese nationality law has applied in Hong Kong since the handover on 1 July 1997. Hong Kong BDTC status ceased to exist and cannot be regained. An interpretation for implementing Chinese nationality law for Hong Kong was presented at the Nineteenth Session of the Standing Committee of the Eighth National People's Congress on 15 May 1996, a year prior to the Hong Kong handover and came into effect on 1 July 1997. The explanations concerning the implementation of the nationality of Hong Kong citizens is that Hong Kong citizens of Chinese descent are Chinese nationals whether or not they have acquired other foreign citizenship(s). Where such Chinese nationals resident in Hong Kong undergo a change of citizenship (e.g. in accordance with Article 9 of the Nationality Law, which provides that a person who becomes settled in a foreign country and acquires foreign citizenship loses his or her Chinese citizenship - Hong Kong is not recognised as foreign territory, before or after 1 July 1997), this must be declared to immigration authorities to be recognised under Chinese nationality law. British nationality acquired in Hong Kong – including BN(O) and under the British Nationality Selection Scheme – are specifically not recognised as a change of nationality because they did not occur after the person became settled in a foreign country. Therefore, a Hong Kong resident who had acquired non-Chinese citizenship would still be recognised as a Chinese citizen after 1 July 1997 (effectively becoming a dual national), but if that person declares the change of nationality to immigration authorities, they would effectively cease to be a Chinese national.

This is reflected in the position the Hong Kong Immigration Department has on Hong Kong permanent residents of Chinese nationality who were Hong Kong permanent residents immediately before 1 July 1997 and hold non-Chinese nationality or citizenship. Those who were permanent residents before the Handover continue to enjoy right of abode in Hong Kong whether they have remained overseas for long time or hold foreign nationality. They however, will not enjoy foreign consular protection in Hong Kong as long as they do not declare a change of nationality to the Immigration Department.[13]

Recent groups eligible for a form of British nationality

British citizenship for non-ethnic Chinese which were wrongfully denied

In February 2006, in response to representations made by Lord Avebury and Tameem Ebrahim,[14] British authorities announced that six hundred British citizenship applications of ethnic minority children of Indian descent from Hong Kong were wrongly refused.[15] The applications dated from the period July 1997 onwards. Where the applicant in such cases confirms that he or she still wishes to receive British citizenship the decision will be reconsidered on request.

British Overseas Citizen status/British citizenship for certain ethnic Indians (new Indian law)

Recent changes to India's Citizenship Act, 1955 (see Indian nationality law) provide that Indian citizenship by descent can no longer be acquired automatically at the time of birth. This amendment will also allow some children of Indian origin born in Hong Kong after 3 December 2004 who have a BN(O) or BOC parent to automatically acquire BOC status at birth under the provisions for reducing statelessness in articles 6(2) and 6(3) of the Hong Kong (British Nationality) Order, 1986. If they have acquired no other nationality after birth, they will be entitled to register for full British citizenship.[16]

British Overseas Citizen status/British citizenship for certain ethnic Nepalese (reinterpretation of Nepalese law)

Recent clarification of Nepal citizenship law has meant a number of persons born in Hong Kong who failed to renounce their British nationality before the age of 21 and were previously thought to be citizens of Nepal are in fact solely British. The British Government has recently accepted that certain Nepalese passport holders born in Hong Kong before 30 June 1976 are BOCs,[17] and can register for British citizenship if they wish to do so.

British citizenship for British Nationals (Overseas) who are otherwise stateless

The passage of the Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act 2009 provides a path for British Nationals (Overseas) who had no other citizenship before 19 March 2009 to apply for British citizenship under s. 4B of the British Nationality Act 1981. To qualify, they must demonstrate that they had not lost or renounced any other nationalities, through action or inaction, on or after 19 March 2009.

Future of the British National (Overseas) status: Lord Goldsmith's citizenship review in 2008

Lord Goldsmith discussed the BN(O) issue in his citizenship review in 2008.[18] He regarded the BN(O) status as "anomalous" in the history of British nationality law, but saw no alternative to preserving this status.[19]

However, Goldsmith stated in February 2020:[20] “I want to make it clear: I never intended my report on citizenship to be a statement on any opinion by me that there would be a breach of the arrangements with China if the UK were to offer greater rights,” he said. “I do not see why the UK government would be in breach of any obligation undertaken in the joint declaration were it to resolve to extend full right of abode to BN(O) passport holders while continuing to honour their side of the Sino-British Joint Declaration.”

See also

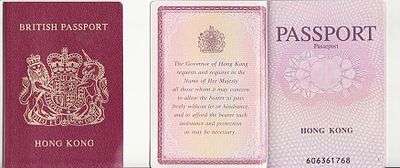

- British passport

- British National (Overseas) passport

- History of British nationality law

- Hong Kong Special Administrative Region passport

- Exit & Entry Permit – issued by the Republic of China (Taiwan) to Hong Kong and Macao residents for entry to Taiwan

- Right of abode in Hong Kong

Government documents

- Lord Goldsmith QC Citizenship Review Citizenship: Our Common Bond

- British citizenship information for persons from Hong Kong of Indian origin

- British citizenship information for persons from Hong Kong of Nepalese origin

- Home Office letter to Lord Avebury, confirming that more than 600 applications for British citizenship from Hong Kong were wrongly refused

- British government statement confirming which persons born in Hong Kong before 1949 acquired British nationality

- British government statement confirming which persons born in Hong Kong between 1949 and 1982 acquired British nationality

- British government statement confirming which persons born in Hong Kong between 1983 and 1997 acquired British nationality

- SUPPORTING BRITISH NATIONALS ABROAD: A GUIDE TO CONSULAR ASSISTANCE

- Reciprocity Schedule (United Kingdom), United States

- Reciprocity Schedule (Hong Kong), United States

- BN(O) passport TV advertisement in 1994

Legislations

Newspapers/Commentaries

- The Transition of Hong Kong People's Nationality after World War II by Michiko Ai

- Nationality of the Chief Executive of the SAR, Democratic Alliance for the Betterment of Hong Kong

- 數字話當年 450萬人持特區護照, Apple Daily

- BNO逐漸走進香港歷史, Wen Wei Po

- BNO護照≠英籍, Mingpao

- SUBMISSION TO LORD GOLDSMITH FOR THE CITIZENSHIP REVIEW: THE DIFFERENT CATEGORIES OF BRITISH NATIONALITY, Immigration Law Practitioners' Association

References

- "Article 6(1), Hong Kong (British Nationality) Order, 1986" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2005.

- Text of the British Nationality Act (Hong Kong) 1990 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk.

- Text of the Hong Kong (War Wives and Widows) Act 1996 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk.

- A Pasage to Nowhere Archived 10 September 2005 at the Wayback Machine (Prism Nov 1995) accessed 1 Aug 2010

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2005.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- The Economist also said that "the failure to offer citizenship to most of Hong Kong's residents was shameful", and "it was the height of cynicism to hand 6 million people over to a regime of proven brutality without allowing them any means to move elsewhere." The article also stated that the real reason that the new Labour government still refused to give full British citizenship to other BDTCs was because if the UK waited until Hong Kong had been disposed of it "would be seen as highly cynical", as The Baroness Symons of Vernham Dean, a Foreign Office minister, conceded. ("Britain's colonial obligations", 3 July 1997, The Economist)

- Text of the British Nationality (Hong Kong) Act 1997 as in force today (including any amendments) within the United Kingdom, from legislation.gov.uk.

- "Registration as a British citizen: British Nationality (Hong Kong) Act 1997". GOV.UK.

- Lord Avebury in the House of Lords

- "Registration as a British citizen: other British nationals". GOV.UK.

- "The Joint Declaration - Memoranda (Exchanged Between the Two Sides)". Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau, The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- Dong Likun, ed. (2016). 中國內地與香港地區法律的衝突與協調 [Conflict and Coordination of Laws of Mainland China and Hong Kong] (in Chinese). Chung Hwa Book Company (Hong Kong). pp. 181–182.

- "The Position of Residents (including Former Residents) of Chinese Nationality who were Permanent Residents Immediately Before 1 July 1997 and Hold Foreign Passports | Immigration Department". www.immd.gov.hk.

- "representations made by Lord Avebury and Tameem Ebrahim, 6 December 2004 (Accessed 1 Aug 2010)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2009.

- "British citizenship applications of ethnic minority children of Indian descent from Hong Kong wrongly refused" (PDF).

- https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld199900/ldhansrd/pdvn/lds04/text/41220w04.htm#column_WA123

- "Foreign & Commonwealth Office". GOV.UK.

- "Wayback Machine" (PDF). 5 April 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 April 2008.

- "Nonetheless to remove this status without putting something significant in its place would be seen as the British reneging on their promise to the people of Hong Kong. The only option which would be characterized as fair would be to offer existing BN(O) holders the right to gain full British citizenship. It is likely that many would not take this up as the prospects economic and fiscal of moving to the UK are not favourable to those well-established in Hong Kong. However, I am advised that this would be a breach of the commitments made between China and the UK in the 1984 Joint Declaration on the future of Hong Kong, an international treaty between the two countries; and that to secure Chinese agreement to vary the terms of that treaty would not be possible. On that basis, I see no alternative but to preserve this one anomalous category of citizenship": Chapter 4, paragraph 12.

- "Britain 'could give Hong Kong BN(O) passport holders' right of abode". South China Morning Post. 24 February 2020.

External links

- 張勇、陳玉田:《香港居民的國籍問題》(出版社:三聯書店(香港)) (Chinese) ISBN 9789620421747

- 《修改英國國籍法的深刻教訓》, Leung Chun Ying, Mingpao, 16 March 2007

- 《人心尚未回歸國人仍需努力》, Leung Chun Ying, Mingpao, 1 June 2007

- Ng Chi-sum, Jane C.Y. Lee and Qu Ayang, Nationality and Right of Abode of Hong Kong Residents – Continuity and Change before and after 1997, 1997, Centre of Asian Studies, Hong Kong University (吳志森, 李正儀, 曲阿陽. 香港居民的國籍和居留權 : 1997年前後的延續與轉變; book in Chinese) ISBN 9789628269037

- Britain's colonial obligations, The Economist, 3 July 1997

- The colonies—Leftovers, The Economist, 3 July 1997

- UK should give British nationality to Hong Kong citizens, Tugendhat says