Baghdad

Baghdad (/ˈbæɡdæd, bəɡˈdæd/; Arabic: بَغْدَاد [baɣˈdaːd] (![]()

Baghdad بَغْدَاد | |

|---|---|

| Mayoralty of Baghdad | |

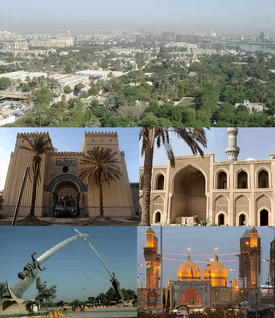

Clockwise from top: Aerial view of the Green Zone; Al-Mustansiriya University; Al-Kadhimiya Mosque; Swords of Qadisiyah monument; and the Iraq Museum | |

Seal | |

| Nickname(s): The City of Peace (مدينة السلام)[1] | |

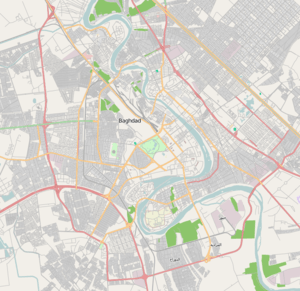

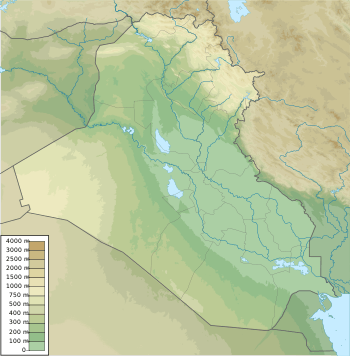

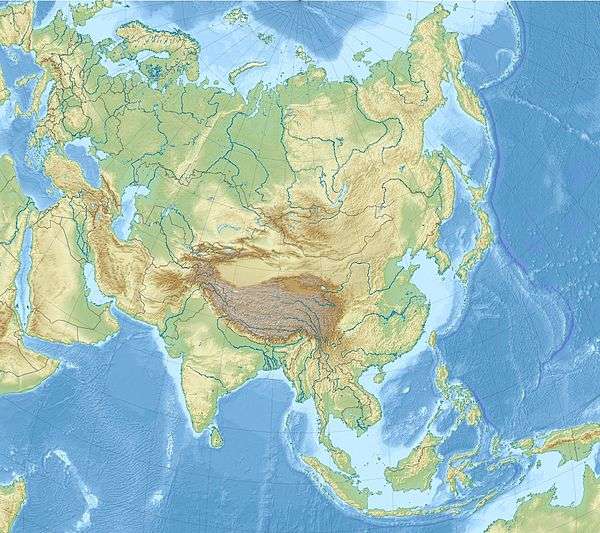

Baghdad Location of Baghdad within Iraq  Baghdad Baghdad (Iraq)  Baghdad Baghdad (Middle East)  Baghdad Baghdad (Asia) | |

| Coordinates: 33°20′N 44°23′E(33.333°N 44.383°E) | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | |

| Established | AD 762 |

| Founded by | Caliph al-Mansur |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Body | Baghdad City Advisory Council |

| • Mayor | Zekra Alwach |

| Area | |

| • Total | 673 km2 (260 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 34 m (112 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2020)[note 1] | 7,144,000 |

| • Rank | 1st |

| Demonym(s) | Baghdadi |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (Arabian Standard Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (No DST) |

| Postal code | 10001 to 10090 |

| Website | Mayoralty of Baghdad |

Baghdad was the largest city in the world for much of the Abbasid era during the Islamic Golden Age, peaking at a population of more than a million.[3] The city was largely destroyed at the hands of the Mongol Empire in 1258, resulting in a decline that would linger through many centuries due to frequent plagues and multiple successive empires. With the recognition of Iraq as an independent state (formerly the British Mandate of Mesopotamia) in 1932, Baghdad gradually regained some of its former prominence as a significant center of Arabic culture, with a population variously estimated at 6 or over 7 million.[note 1]

In contemporary times, the city has often faced severe infrastructural damage, most recently due to the United States-led 2003 invasion of Iraq, and the subsequent Iraq War that lasted until December 2011. In recent years, the city has been frequently subjected to insurgent attacks, resulting in a substantial loss of cultural heritage and historical artifacts as well. As of 2018, Baghdad was listed as one of the least hospitable places in the world to live, ranked by Mercer as the worst major city for quality of life in the world.[8]

Name

The name Baghdad is pre-Islamic, and its origin is disputed.[9] The site where the city of Baghdad developed has been populated for millennia. By the 8th century AD, several villages had developed there, including a Persian[10][11] hamlet called Baghdad, the name which would come to be used for the Abbasid metropolis.[12]

Arab authors, realizing the pre-Islamic origins of Baghdad's name, generally looked for its roots in Middle Persian.[9] They suggested various meanings, the most common of which was "bestowed by God".[9] Modern scholars generally tend to favor this etymology,[9] which views the word as a compound of bagh (![]()

![]()

A few authors have suggested older origins for the name, in particular the name Bagdadu or Hudadu that existed in Old Babylonian (spelled with a sign that can represent both bag and hu), and the Babylonian Talmudic name of a place called "Baghdatha".[9][19][20] Some scholars suggested Aramaic derivations.[9]

When the Abbasid caliph, Al-Mansur, founded a completely new city for his capital, he chose the name Madinat al-Salaam or City of Peace. This was the official name on coins, weights, and other official usage, although the common people continued to use the old name.[21][22] By the 11th century, "Baghdad" became almost the exclusive name for the world-renowned metropolis.

History

Foundation

_p008_View_of_Bagdad_on_the_Persian_side_of_the_Tigris.jpg)

After the fall of the Umayyads, the first Muslim dynasty, the victorious Abbasid rulers wanted their own capital from which they could rule. They chose a site north of the Sassanid capital of Ctesiphon (and also just north of where ancient Babylon had once stood), and on 30 July 762[23] the caliph Al-Mansur commissioned the construction of the city. It was built under the supervision of the Barmakids.[24] Mansur believed that Baghdad was the perfect city to be the capital of the Islamic empire under the Abbasids. Mansur loved the site so much he is quoted saying: "This is indeed the city that I am to found, where I am to live, and where my descendants will reign afterward".[25]

The city's growth was helped by its excellent location, based on at least two factors: it had control over strategic and trading routes along the Tigris, and it had an abundance of water in a dry climate. Water exists on both the north and south ends of the city, allowing all households to have a plentiful supply, which was very uncommon during this time. The city of Baghdad soon became so large that it had to be divided into three judicial districts: Madinat al-Mansur (the Round City), al-Sharqiyya (Karkh) and Askar al-Mahdi (on the West Bank).[26]

Baghdad eclipsed Ctesiphon, the capital of the Sassanians, which was located some 30 km (19 mi) to the southeast. Today, all that remains of Ctesiphon is the shrine town of Salman Pak, just to the south of Greater Baghdad. Ctesiphon itself had replaced and absorbed Seleucia, the first capital of the Seleucid Empire, which had earlier replaced the city of Babylon.

According to the traveler Ibn Battuta, Baghdad was one of the largest cities, not including the damage it has received. The residents are mostly Hanbal. Baghdad is also home to the grave of Abu Hanifa where there is a cell and a mosque above it. The Sultan of Baghdad, Abu Said Bahadur Khan, was a Tatar king who embraced Islam.[27]

In its early years, the city was known as a deliberate reminder of an expression in the Qur'an, when it refers to Paradise.[28] It took four years to build (764–768). Mansur assembled engineers, surveyors, and art constructionists from around the world to come together and draw up plans for the city. Over 100,000 construction workers came to survey the plans; many were distributed salaries to start the building of the city.[29] July was chosen as the starting time because two astrologers, Naubakht Ahvazi and Mashallah, believed that the city should be built under the sign of the lion, Leo.[30] Leo is associated with fire and symbolises productivity, pride, and expansion.

The bricks used to make the city were 18 inches (460 mm) on all four sides. Abu Hanifah was the counter of the bricks and he developed a canal, which brought water to the work site for both human consumption and the manufacture of the bricks. Marble was also used to make buildings throughout the city, and marble steps led down to the river's edge.

The basic framework of the city consists of two large semicircles about 19 km (12 mi) in diameter. The city was designed as a circle about 2 km (1.2 mi) in diameter, leading it to be known as the "Round City". The original design shows a single ring of residential and commercial structures along the inside of the city walls, but the final construction added another ring inside the first.[31] Within the city there were many parks, gardens, villas, and promenades.[32] In the center of the city lay the mosque, as well as headquarters for guards. The purpose or use of the remaining space in the center is unknown. The circular design of the city was a direct reflection of the traditional Persian Sasanian urban design. The Sasanian city of Gur in Fars, built 500 years before Baghdad, is nearly identical in its general circular design, radiating avenues, and the government buildings and temples at the centre of the city. This style of urban planning contrasted with Ancient Greek and Roman urban planning, in which cities are designed as squares or rectangles with streets intersecting each other at right angles.

- Surrounding walls

The four surrounding walls of Baghdad were named Kufa, Basra, Khurasan, and Syria; named because their gates pointed in the directions of these destinations. The distance between these gates was a little less than 2.4 km (1.5 mi). Each gate had double doors that were made of iron; the doors were so heavy it took several men to open and close them. The wall itself was about 44 m thick at the base and about 12 m thick at the top. Also, the wall was 30 m high, which included merlons, a solid part of an embattled parapet usually pierced by embrasures. This wall was surrounded by another wall with a thickness of 50 m. The second wall had towers and rounded merlons, which surrounded the towers. This outer wall was protected by a solid glacis, which is made out of bricks and quicklime. Beyond the outer wall was a water-filled moat.

- Golden Gate Palace

The Golden Gate Palace, the residence of the caliph and his family, was in the middle of Baghdad, in the central square. In the central part of the building, there was a green dome that was 39 m high. Surrounding the palace was an esplanade, a waterside building, in which only the caliph could come riding on horseback. In addition, the palace was near other mansions and officer's residences. Near the Gate of Syria, a building served as the home for the guards. It was made of brick and marble. The palace governor lived in the latter part of the building and the commander of the guards in the front. In 813, after the death of caliph Al-Amin, the palace was no longer used as the home for the caliph and his family.[33] The roundness points to the fact that it was based on Arabic script.[34][35] The two designers who were hired by Al-Mansur to plan the city's design were Naubakht, a Zoroastrian who also determined that the date of the foundation of the city would be astrologically auspicious, and Mashallah, a Jew from Khorasan, Iran.[36]

Center of learning (8th to 9th centuries)

.jpg)

Within a generation of its founding, Baghdad became a hub of learning and commerce. The city flourished into an unrivaled intellectual center of science, medicine, philosophy, and education, especially with the Abbasid Translation Movement began under the second caliph Al-Mansur and thrived under the seventh caliph Al-Ma'mun.[37] Baytul-Hikmah or the "House of Wisdom" was among the most well known academies,[38] and had the largest selection of books in the world by the middle of the 9th century. Notable scholars based in Baghdad during this time include translator Hunayn ibn Ishaq, mathematician al-Khwarizmi, and philosopher Al-Kindi.[38] Although Arabic was used as the international language of science, the scholarship involved not only Arabs, but also Persians, Syriacs,[39] Nestorians, Jews, Arab Christians,[40][41] and people from other ethnic and religious groups native to the region.[42][43][44][45][46] These are considered among the fundamental elements that contributed to the flourishing of scholarship in the Medieval Islamic world.[47][48][49] Baghdad was also a significant center of Islamic religious learning, with Al-Jahiz contributing to the formation of Mu'tazili theology, as well as Al-Tabari culminating the scholarship on the Quranic exegesis.[37] Baghdad was likely the largest city in the world from shortly after its foundation until the 930s, when it tied with Córdoba.[50] Several estimates suggest that the city contained over a million inhabitants at its peak.[51] Many of the One Thousand and One Nights tales, widely known as the Arabian Nights, are set in Baghdad during this period.

Among the notable features of Baghdad during this period were its exceptional libraries. Many of the Abbasid caliphs were patrons of learning and enjoyed collecting both ancient and contemporary literature. Although some of the princes of the previous Umayyad dynasty had begun to gather and translate Greek scientific literature, the Abbasids were the first to foster Greek learning on a large scale. Many of these libraries were private collections intended only for the use of the owners and their immediate friends, but the libraries of the caliphs and other officials soon took on a public or a semi-public character.[52] Four great libraries were established in Baghdad during this period. The earliest was that of the famous Al-Ma'mun, who was caliph from 813 to 833. Another was established by Sabur ibn Ardashir in 991 or 993 for the literary men and scholars who frequented his academy.[52] Unfortunately, this second library was plundered and burned by the Seljuks only seventy years after it was established. This was a good example of the sort of library built up out of the needs and interests of a literary society.[52] The last two were examples of madrasa or theological college libraries. The Nezamiyeh was founded by the Persian Nizam al-Mulk, who was vizier of two early Seljuk sultans.[52] It continued to operate even after the coming of the Mongols in 1258. The Mustansiriyah madrasa, which owned an exceedingly rich library, was founded by Al-Mustansir, the second last Abbasid caliph, who died in 1242.[52] This would prove to be the last great library built by the caliphs of Baghdad.

Stagnation and invasions (10th to 16th centuries)

By the 10th century, the city's population was between 1.2 million[53] and 2 million.[54] Baghdad's early meteoric growth eventually slowed due to troubles within the Caliphate, including relocations of the capital to Samarra (during 808–819 and 836–892), the loss of the western and easternmost provinces, and periods of political domination by the Iranian Buwayhids (945–1055) and Seljuk Turks (1055–1135).

The Seljuks were a clan of the Oghuz Turks from Central Asia that converted to the Sunni branch of Islam. In 1040, they destroyed the Ghaznavids, taking over their land and in 1055, Tughril Beg, the leader of the Seljuks, took over Baghdad. The Seljuks expelled the Buyid dynasty of Shiites that had ruled for some time and took over power and control of Baghdad. They ruled as Sultans in the name of the Abbasid caliphs (they saw themselves as being part of the Abbasid regime). Tughril Beg saw himself as the protector of the Abbasid Caliphs.[55]

Sieges and wars in which Baghdad was involved are listed below:

- Siege of Baghdad (812–813), Fourth Fitna (Caliphal Civil War)

- Siege of Baghdad (865), Abbasid Civil War (865–866)

- Battle of Baghdad (946), Buyid–Hamdanid War

- Siege of Baghdad (1157), Abbasid–Seljuq Wars

- Siege of Baghdad (1258), Mongol conquest of Baghdad

- Siege of Baghdad (1393), by Tamerlane

- Siege of Baghdad (1401), by Tamerlane

- Capture of Baghdad (1534), Ottoman–Safavid Wars

- Capture of Baghdad (1623), Ottoman–Safavid Wars

- Siege of Baghdad (1625), Ottoman–Safavid Wars

- Capture of Baghdad (1638), Ottoman–Safavid Wars

In 1058, Baghdad was captured by the Fatimids under the Turkish general Abu'l-Ḥārith Arslān al-Basasiri, an adherent of the Ismailis along with the 'Uqaylid Quraysh.[56] Not long before the arrival of the Saljuqs in Baghdad, al-Basasiri petitioned to the Fatimid Imam-Caliph al-Mustansir to support him in conquering Baghdad on the Ismaili Imam's behalf. It has recently come to light that the famed Fatimid da'i, al-Mu'ayyad al-Shirazi, had a direct role in supporting al-Basasiri and helped the general to succeed in taking Mawṣil, Wāsit and Kufa. Soon after,[57] by December 1058, a Shi'i adhān (call to prayer) was implemented in Baghdad and a khutbah (sermon) was delivered in the name of the Fatimid Imam-Caliph.[57] Despite his Shi'i inclinations, Al-Basasiri received support from Sunnis and Shi'is alike, for whom opposition to the Saljuq power was a common factor.[58]

On 10 February 1258, Baghdad was captured by the Mongols led by Hulegu, a grandson of Chingiz Khan (Genghis Khan), during the siege of Baghdad.[59] Many quarters were ruined by fire, siege, or looting. The Mongols massacred most of the city's inhabitants, including the caliph Al-Musta'sim, and destroyed large sections of the city. The canals and dykes forming the city's irrigation system were also destroyed. During this time, in Baghdad, Christians and Shia were tolerated, while Sunnis were treated as enemies.[60] The sack of Baghdad put an end to the Abbasid Caliphate.[61] It has been argued that this marked an end to the Islamic Golden Age and served a blow from which Islamic civilisation never fully recovered.[62]

At this point, Baghdad was ruled by the Ilkhanate, a breakaway state of the Mongol Empire, ruling from Iran. In August 1393, Baghdad was occupied by the Central Asian Turkic conqueror Timur ("Tamerlane"),[63] by marching there in only eight days from Shiraz. Sultan Ahmad Jalayir fled to Syria, where the Mamluk Sultan Barquq protected him and killed Timur's envoys. Timur left the Sarbadar prince Khwaja Mas'ud to govern Baghdad, but he was driven out when Ahmad Jalayir returned.

In 1401, Baghdad was again sacked, by Timur.[64] When his forces took Baghdad, he spared almost no one, and ordered that each of his soldiers bring back two severed human heads.[65] Baghdad became a provincial capital controlled by the Mongol Jalayirid (1400–1411), Turkic Kara Koyunlu (1411–1469), Turkic Ak Koyunlu (1469–1508), and the Iranian Safavid (1508–1534) dynasties.

Ottoman era (16th to 19th centuries)

In 1534, Baghdad was captured by the Ottoman Turks. Under the Ottomans, Baghdad continued into a period of decline, partially as a result of the enmity between its rulers and Iranian Safavids, which did not accept the Sunni control of the city. Between 1623 and 1638, it returned to Iranian rule before falling back into Ottoman hands. Baghdad has suffered severely from visitations of the plague and cholera,[66] and sometimes two-thirds of its population has been wiped out.[67]

For a time, Baghdad had been the largest city in the Middle East. The city saw relative revival in the latter part of the 18th century, under a Mamluk government. Direct Ottoman rule was reimposed by Ali Rıza Pasha in 1831. From 1851 to 1852 and from 1861 to 1867, Baghdad was governed, under the Ottoman Empire by Mehmed Namık Pasha.[68] The Nuttall Encyclopedia reports the 1907 population of Baghdad as 185,000.

.png) Baghdad Eyalet in 1609 CE.

Baghdad Eyalet in 1609 CE..png) Baghdad Vilayet in 1900 CE.

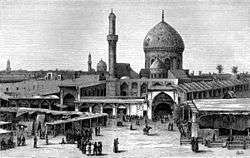

Baghdad Vilayet in 1900 CE. Souk in Baghdad, 1876 CE.

Souk in Baghdad, 1876 CE.

20th and 21st centuries

Baghdad and southern Iraq remained under Ottoman rule until 1917, when captured by the British during World War I. In 1920, Baghdad became the capital of the British Mandate of Mesopotamia with several architectural and planning projects commissioned to reinforce this administration.[69] After receiving independence in 1932, the capital of the Kingdom of Iraq. The city's population grew from an estimated 145,000 in 1900 to 580,000 in 1950. During the Mandate, Baghdad's substantial Jewish community comprised a quarter of the city's population.[70] On 1 April 1941, members of the "Golden Square" and Rashid Ali staged a coup in Baghdad. Rashid Ali installed a pro-German and pro-Italian government to replace the pro-British government of Regent Abdul Ilah. On 31 May, after the resulting Anglo-Iraqi War and after Rashid Ali and his government had fled, the Mayor of Baghdad surrendered to British and Commonwealth forces. On 14 July 1958, members of the Iraqi Army, under Abd al-Karim Qasim, staged a coup to topple the Kingdom of Iraq. King Faisal II, former Prime Minister Nuri as-Said, former Regent Prince 'Abd al-Ilah, members of the royal family, and others were brutally killed during the coup. Many of the victim's bodies were then dragged through the streets of Baghdad.

During the 1970s, Baghdad experienced a period of prosperity and growth because of a sharp increase in the price of petroleum, Iraq's main export. New infrastructure including modern sewerage, water, and highway facilities were built during this period. The masterplans of the city (1967, 1973) were delivered by the Polish planning office Miastoprojekt-Kraków, mediated by Polservice.[71] However, the Iran–Iraq War of the 1980s was a difficult time for the city, as money was diverted by Saddam Hussein to the army and thousands of residents were killed. Iran launched a number of missile attacks against Baghdad in retaliation for Saddam Hussein's continuous bombardments of Tehran's residential districts. In 1991 and 2003, the Gulf War and the 2003 invasion of Iraq caused significant damage to Baghdad's transportation, power, and sanitary infrastructure as the US-led coalition forces launched massive aerial assaults in the city in the two wars. Also in 2003, the minor riot in the city (which took place on 21 July) caused some disturbance in the population. The historic "Assyrian Quarter" of the city, Dora, which boasted a population of 150,000 Assyrians in 2003, made up over 3% of the capital's Assyrian population then. The community has been subject to kidnappings, death threats, vandalism, and house burnings by Al-Qaeda and other insurgent groups. As of the end of 2014, only 1,500 Assyrians remained in Dora.[72]

Main sights

.jpg)

Points of interest include the National Museum of Iraq whose collection of artifacts was looted during the 2003 invasion, and the iconic Hands of Victory arches. Multiple Iraqi parties are in discussions as to whether the arches should remain as historical monuments or be dismantled. Thousands of ancient manuscripts in the National Library were destroyed under Saddam's command.

Mutanabbi Street

Mutanabbi Street is located near the old quarter of Baghdad; at Al Rasheed Street. It is the historic center of Baghdadi book-selling, a street filled with bookstores and outdoor book stalls. It was named after the 10th-century classical Iraqi poet Al-Mutanabbi.[73] This street is well established for bookselling and has often been referred to as the heart and soul of the Baghdad literacy and intellectual community.

Baghdad Zoo

The zoological park used to be the largest in the Middle East. Within eight days following the 2003 invasion, however, only 35 of the 650 animals in the facility survived. This was a result of theft of some animals for human food, and starvation of caged animals that had no food. South African Lawrence Anthony and some of the zoo keepers cared for the animals and fed the carnivores with donkeys they had bought locally.[74][75] Eventually, Paul Bremer, Director of the Coalition Provisional Authority in Iraq from 11 May 2003 to 28 June 2004 ordered protection of the zoo and U.S. engineers helped to reopen the facility.[74]

Grand Festivities Square

Grand Festivities Square is the main square where public celebrations are held and is also the home to three important monuments commemorating Iraqi's fallen soldiers and victories in war; namely Al-Shaheed Monument, the Victory Arch and the Unknown Soldier's Monument.[76]

Al-Shaheed Monument

Al-Shaheed Monument, also known as the Martyr's Memorial, is a monument dedicated to the Iraqi soldiers who died in the Iran–Iraq War. However, now it is generally considered by Iraqis to be for all of the martyrs of Iraq, especially those allied with Iran and Syria fighting ISIS, not just of the Iran–Iraq War. The monument was opened in 1983, and was designed by the Iraqi architect Saman Kamal and the Iraqi sculptor and artist Ismail Fatah Al Turk. During the 1970s and 1980s, Saddam Hussein's government spent a lot of money on new monuments, which included the al-Shaheed Monument.[77]

- Al-Shaheed, (Martyr's Monument), Zawra Park, Baghdad

.jpg) The Victory Arch (officially known as the Swords of Qādisīyah

The Victory Arch (officially known as the Swords of Qādisīyah

Qushla

Qushla or Qishla is a public square and the historical complex located in Rusafa neighborhood at the riverbank of Tigris. Qushla and its surroundings is where the historical features and cultural capitals of Baghdad are concentrated, from the Mutanabbi Street, Abbasid-era palace and bridges, Ottoman-era mosques to the Mustansariyah Madrasa. The square developed during the Ottoman era as a military barracks. Today, it is a place where the citizens of Baghdad find leisure such as reading poetry in gazebos.[78] It is characterized by the iconic clock tower which was donated by George V. The entire area is submitted to the UNESCO World Heritage Site Tentative list.[79]

Mosques

- Masjid Al-Kadhimain is a shrine that is located in the Kādhimayn suburb of Baghdad. It contains the tombs of the seventh and ninth Twelver Shi'ite Imams, Musa al-Kadhim and Muhammad at-Taqi respectively, upon whom the title of Kāẓimayn ("Two who swallow their anger") was bestowed.[80][81][82] Many Shi'ites travel to the mosque from far away places to commemorate.

- A'dhamiyyah is a predominantly Sunni area with a Masjid that is associated with the Sunni Imam Abu Hanifah. The name of Al-Aʿẓamiyyah is derived from Abu Hanifah's title, al-Imām al-Aʿẓam (the Great Imam).[83][84]

Firdos Square

Firdos Square is a public open space in Baghdad and the location of two of the best-known hotels, the Palestine Hotel and the Sheraton Ishtar, which are both also the tallest buildings in Baghdad.[85] The square was the site of the statue of Saddam Hussein that was pulled down by U.S. coalition forces in a widely televised event during the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

Administrative divisions

Administratively, Baghdad Governorate is divided into districts which are further divided into sub-districts. Municipally, the governorate is divided into 9 municipalities, which have responsibility for local issues. Regional services, however, are coordinated and carried out by a mayor who oversees the municipalities. There is no single city council that singularly governs Baghdad at a municipal level. The governorate council is responsible for the governorate-wide policy. These official subdivisions of the city served as administrative centres for the delivery of municipal services but until 2003 had no political function. Beginning in April 2003, the U.S. controlled Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA) began the process of creating new functions for these. The process initially focused on the election of neighbourhood councils in the official neighbourhoods, elected by neighbourhood caucuses. The CPA convened a series of meetings in each neighbourhood to explain local government, to describe the caucus election process and to encourage participants to spread the word and bring friends, relatives and neighbours to subsequent meetings. Each neighbourhood process ultimately ended with a final meeting where candidates for the new neighbourhood councils identified themselves and asked their neighbours to vote for them. Once all 88 (later increased to 89) neighbourhood councils were in place, each neighbourhood council elected representatives from among their members to serve on one of the city's nine district councils. The number of neighbourhood representatives on a district council is based upon the neighbourhood's population. The next step was to have each of the nine district councils elect representatives from their membership to serve on the 37 member Baghdad City Council. This three tier system of local government connected the people of Baghdad to the central government through their representatives from the neighbourhood, through the district, and up to the city council. The same process was used to provide representative councils for the other communities in Baghdad Province outside of the city itself. There, local councils were elected from 20 neighbourhoods (Nahia) and these councils elected representatives from their members to serve on six district councils (Qada). As within the city, the district councils then elected representatives from among their members to serve on the 35 member Baghdad Regional Council. The first step in the establishment of the system of local government for Baghdad Province was the election of the Baghdad Provincial Council. As before, the representatives to the Provincial Council were elected by their peers from the lower councils in numbers proportional to the population of the districts they represent. The 41 member Provincial Council took office in February 2004 and served until national elections held in January 2005, when a new Provincial Council was elected. This system of 127 separate councils may seem overly cumbersome; however, Baghdad Province is home to approximately seven million people. At the lowest level, the neighbourhood councils, each council represents an average of 75,000 people. The nine District Advisory Councils (DAC) are as follows:[86]

- Adhamiyah

- Karkh (Green Zone)[87]

- Karrada[88][89]

- Kadhimiya[90]

- Mansour

- Sadr City (Thawra)[91]

- Al Rashid[92]

- Rusafa

- New Baghdad (Tisaa Nissan) (9 April)[93]

The nine districts are subdivided into 89 smaller neighborhoods which may make up sectors of any of the districts above. The following is a selection (rather than a complete list) of these neighborhoods:

- Al-Ghazaliya

- Al-A'amiriya

- Dora

- Karrada

- Al-Jadriya

- Al-Hebnaa

- Zayouna

- Al-Saydiya

- Al-Sa'adoon

- Al-Shu'ala

- Al-Mahmudiyah

- Bab Al-Moatham

- Al-Za'franiya

- Hayy Ur

- Sha'ab

- Hayy Al-Jami'a

- Al-Adel

- Al Khadhraa

- Hayy Al-Jihad

- Hayy Al-A'amel

- Hayy Aoor

- Al-Hurriya

- Hayy Al-Shurtta

- Yarmouk

- Jesr Diyala

- Abu Disher

- Raghiba Khatoun

- Arab Jibor

- Al-Fathel

- Al-Ubedy

- Al-Washash

- Al-Wazireya

Geography

The city is located on a vast plain bisected by the Tigris river. The Tigris splits Baghdad in half, with the eastern half being called "Risafa" and the Western half known as "Karkh". The land on which the city is built is almost entirely flat and low-lying, being of alluvial origin due to the periodic large floods which have occurred on the river.

Climate

Baghdad has a hot desert climate (Köppen BWh), featuring extremely hot, prolonged, dry summers and mild to cool, slightly wet, short winters. In the summer, from June through August, the average maximum temperature is as high as 44 °C (111 °F) and accompanied by sunshine. Rainfall has been recorded on fewer than half a dozen occasions at this time of year and has never exceeded 1 millimetre (0.04 in).[94] Even at night, temperatures in summer are seldom below 24 °C (75 °F). Baghdad's record highest temperature of 51.8 °C (125.2 °F) was reached on 28 July 2020.[95][96] The humidity is typically under 50% in summer due to Baghdad's distance from the marshy southern Iraq and the coasts of Persian Gulf, and dust storms from the deserts to the west are a normal occurrence during the summer.

Winter temperatures are typical of hot desert climates. From December through February, Baghdad has maximum temperatures averaging 16 to 19 °C (61 to 66 °F), though highs above 21 °C (70 °F) are not unheard of. Lows below freezing occur a couple of times per year on average.[97]

Annual rainfall, almost entirely confined to the period from November through March, averages approximately 150 mm (5.91 in), but has been as high as 338 mm (13.31 in) and as low as 37 mm (1.46 in).[98] On 11 January 2008, light snow fell across Baghdad for the first time in 100 years.[99] Snowfall was again reported on 11 February 2020, with accumulations across the city.[100]

| Climate data for Baghdad | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 15.5 (59.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

23.6 (74.5) |

29.9 (85.8) |

36.5 (97.7) |

41.3 (106.3) |

44.0 (111.2) |

43.5 (110.3) |

40.2 (104.4) |

33.4 (92.1) |

23.7 (74.7) |

17.2 (63.0) |

30.6 (87.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.7 (49.5) |

12 (54) |

16.6 (61.9) |

22.6 (72.7) |

28.3 (82.9) |

32.3 (90.1) |

34.8 (94.6) |

34 (93) |

30.5 (86.9) |

24.7 (76.5) |

16.5 (61.7) |

11.2 (52.2) |

22.8 (73.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.8 (38.8) |

5.5 (41.9) |

9.6 (49.3) |

15.2 (59.4) |

20.1 (68.2) |

23.3 (73.9) |

25.5 (77.9) |

24.5 (76.1) |

20.7 (69.3) |

15.9 (60.6) |

9.2 (48.6) |

5.1 (41.2) |

14.9 (58.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 26 (1.0) |

28 (1.1) |

28 (1.1) |

17 (0.7) |

7 (0.3) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

3 (0.1) |

21 (0.8) |

26 (1.0) |

156 (6.1) |

| Average rainy days | 5 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 34 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 71 | 61 | 53 | 43 | 30 | 21 | 22 | 22 | 26 | 34 | 54 | 71 | 42 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 192.2 | 203.4 | 244.9 | 255.0 | 300.7 | 348.0 | 347.2 | 353.4 | 315.0 | 272.8 | 213.0 | 195.3 | 3,240.9 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 3 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Source 1: World Meteorological Organization (UN)[101] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Climate & Temperature[102][103] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Baghdad's population was estimated at 7.22 million in 2015. The city historically had a predominantly Sunni population, but by the early 21st century around 82% of the city's population were Iraqi Shi'ites. At the beginning of the 21st century, some 1.5 million people migrated to Baghdad, most of them Shiites and a few Sunnis. Sunni Muslims make up 23% of Iraq's population and they are still a majority in west and north Iraq. As early as 2003, about 20 percent of the population of the city was the result of mixed marriages between Shi'ites and Sunnis: they are often referred to as "Sushis".[104] Following the sectarian violence in Iraq between the Sunni and Shia militia groups during the U.S. occupation of Iraq, the city's population became overwhelmingly Shia. Despite the government's promise to resettle Sunnis displaced by the violence, little has been done to bring this about. The Iraqi Civil War following ISIS' invasion in 2014 caused hundreds of thousands of Iraqi internally displaced people to flee to the city. The city has Sunni, Shia, Assyrian/Chaldean/Syriacs, Armenians and mixed neighborhoods. The city was also home to a large Jewish community and regularly visited by Sikh pilgrims.

Economy

Baghdad accounts for 22.2 per cent of Iraq's population and 40 per cent of the country's gross domestic product (PPP). Iraqi Airways, the national airline of Iraq, has its headquarters on the grounds of Baghdad International Airport in Baghdad.[105]

Reconstruction efforts

Most Iraqi reconstruction efforts have been devoted to the restoration and repair of badly damaged urban infrastructure. More visible efforts at reconstruction through private development, like architect and urban designer Hisham N. Ashkouri's Baghdad Renaissance Plan and the Sindbad Hotel Complex and Conference Center have also been made.[106] A plan was proposed by a Government agency to rebuild a tourist island in 2008.[107] In late 2009, a construction plan was proposed to rebuild the heart of Baghdad, but the plan was never realized because corruption was involved in it.[108]

The Baghdad Eye, a 198 m (650 ft) tall Ferris wheel, was proposed for Baghdad in August 2008. At that time, three possible locations had been identified, but no estimates of cost or completion date were given.[109][110][111][112] In October 2008, it was reported that Al-Zawraa Park was expected to be the site,[113] and a 55 m (180 ft) wheel was installed there in March 2011.[114]

Iraq's Tourism Board is also seeking investors to develop a "romantic" island on the River Tigris in Baghdad that was once a popular honeymoon spot for newlywed Iraqis. The project would include a six-star hotel, spa, an 18-hole golf course and a country club. In addition, the go-ahead has been given to build numerous architecturally unique skyscrapers along the Tigris that would develop the city's financial centre in Kadhehemiah.[109]

In October 2008, the Baghdad Metro resumed service. It connects the center to the southern neighborhood of Dora. In May 2010, a new residential and commercial project nicknamed Baghdad Gate was announced.[115] This project not only addresses the urgent need for new residential units in Baghdad but also acts as a real symbol of progress in the war torn city, as Baghdad has not seen projects of this scale for decades.[116]

Education

The Mustansiriya Madrasah was established in 1227 by the Abbasid Caliph al-Mustansir. The name was changed to Al-Mustansiriya University in 1963. The University of Baghdad is the largest university in Iraq and the second largest in the Arab world. Prior to the Gulf War, multiple international schools operated in Baghdad, including:

Culture

Baghdad has always played a significant role in the broader Arab cultural sphere, contributing several significant writers, musicians and visual artists. Famous Arab poets and singers such as Nizar Qabbani, Umm Kulthum, Fairuz, Salah Al-Hamdani, Ilham al-Madfai and others have performed for the city. The dialect of Arabic spoken in Baghdad today differs from that of other large urban centres in Iraq, having features more characteristic of nomadic Arabic dialects (Versteegh, The Arabic Language). It is possible that this was caused by the repopulating of the city with rural residents after the multiple sackings of the late Middle Ages. For poetry written about Baghdad, see Reuven Snir (ed.), Baghdad: The City in Verse (Harvard, 2013)[120] Baghdad joined the UNESCO Creative Cities Network as a City of Literature in December 2015.[121]

Institutions

Some of the important cultural institutions in the city include the National Theater, which was looted during the 2003 invasion of Iraq, but efforts are underway to restore the theatre.[122] The live theatre scene received a boost during the 1990s, when UN sanctions limited the import of foreign films. As many as 30 movie theatres were reported to have been converted to live stages, producing a wide range of comedies and dramatic productions.[123] Institutions offering cultural education in Baghdad include The Music and Ballet School of Baghdad and the Institute of Fine Arts Baghdad. The Iraqi National Symphony Orchestra is a government funded symphony orchestra in Baghdad. The INSO plays primarily classical European music, as well as original compositions based on Iraqi and Arab instruments and music. Baghdad is also home to a number of museums which housed artifacts and relics of ancient civilization; many of these were stolen, and the museums looted, during the widespread chaos immediately after United States forces entered the city.

During the 2003 occupation of Iraq, AFN Iraq ("Freedom Radio") broadcast news and entertainment within Baghdad, among other locations. There is also a private radio station called "Dijlah" (named after the Arabic word for the Tigris River) that was created in 2004 as Iraq's first independent talk radio station. Radio Dijlah offices, in the Jamia neighborhood of Baghdad, have been attacked on several occasions.[124]

Destruction of cultural heritage

Priceless collection of artifacts in the National Museum of Iraq was looted during the 2003 US-led invasion. Thousands of ancient manuscripts in the National Library were destroyed under Saddam's command and because of neglect by the occupying coalition forces.[125]

Sport

Baghdad is home to some of the most successful football (soccer) teams in Iraq, the biggest being Al-Shorta (Police), Al-Quwa Al-Jawiya (Airforce club), Al-Zawra'a, and Talaba (Students). The largest stadium in Baghdad is Al-Shaab Stadium, which was opened in 1966. The city has also had a strong tradition of horse racing ever since World War I, known to Baghdadis simply as 'Races'. There are reports of pressures by the Islamists to stop this tradition due to the associated gambling.

Major streets

- Haifa Street

- Salihiya Residential area - situated off Al Sinak bridge in central Baghdad, surrounded by Al- Mansur Hotel in the north and Al-Rasheed hotel in the south

- Hilla Road – Runs from the south into Baghdad via Yarmouk (Baghdad)

- Caliphs Street – site of historical mosques and churches

- Sadoun Street – stretching from Liberation Square to Masbah

- Mohammed Al-Qassim highway near Adhamiyah

- Abu Nuwas Street – runs along the Tigris from the Jumhouriya Bridge to 14 July Suspended Bridge

- Damascus Street – goes from Damascus Square to the Baghdad Airport Road

- Mutanabbi Street – A street with numerous bookshops, named after the 10th century Iraqi poet Al-Mutanabbi

- Rabia Street

- Arbataash Tamuz (14th July) Street (Mosul Road)

- Muthana al-Shaibani Street

- Bor Saeed (Port Said) Street

- Thawra Street

- Al Qanat Street – runs through Baghdad north-south

- Al Khat al Sare'a – Mohammed al Qasim (high speed lane) – runs through Baghdad, north–south

- Al Sinaa Street (Industry Street) runs by the University of Technology – centre of the computer trade in Baghdad

- Al Nidhal Street

- Al Rasheed Street – city centre Baghdad

- Al Jamhuriah Street – city centre Baghdad

- Falastin Street

- Tariq el Muaskar – (Al Rasheed Camp Road)

- Akhrot street

- Baghdad Airport Road [126]

Twin towns/Sister cities

See also

Notes

- Estimates of total population differ substantially. The CIA World Factbook estimated the 2020 population of Baghdad at 7,144,000[4] The Encyclopedia Britannica estimated the 2005 population at 5,904,000;[5] the 2006 Lancet Report states a population of 7,216,050;[6] Mongabay gives a figure of 6,492,200 as of 2002.[7]

References

- Petersen, Andrew (13 September 2011). "Baghdad (Madinat al-Salam)". Islamic Arts & Architecture. Archived from the original on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- Thomas A. Carlson; et al. (30 June 2014), "Baghdad — ܒܓܕܕ", The Syriac Gazetteer

- "Largest Cities Through History". Geography.about.com. 6 April 2011. Archived from the original on 27 May 2005. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- "Middle East :: Iraq". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- "Baghdad" Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 19 July 2019.

- Gilbert Burnham; Riyadh Lafta; Shannon Doocy; Les Roberts (11 October 2006). "Mortality after the 2003 invasion of Iraq: a cross-sectional cluster sample survey". The Lancet. 368 (9545): 1421–1428. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.88.4036. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69491-9. PMID 17055943. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2013. (110 KB)

- "Cities and urban areas in Iraq with population over 100,000" Archived 15 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Mongabay.com

- Vienna unbeatable as world's most liveable city, Baghdad still worst. Reuters. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- Duri, A.A. (2012). "Bag̲h̲dād". In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0084.

- "Baghdad, Foundation and early growth". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

[...] the site located between present-day Al-Kāẓimiyyah and Al-Karkh and occupied by a Persian village called Baghdad, was selected by al-Manṣūr, the second caliph of the Abbāsid dynasty, for his capital.

- Le Strange, G. (n.d.). [...] The Persian hamlet of Baghdad, on the Western bank of the Tigris, and just above where Sarat canal flowed in, was ultimately fixed upon [...]. In Baghdad during the Abbasid Caliphate (p. 9).

- E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam 1913-1936. 1987. ISBN 978-9004082656.

- Mackenzie, D. (1971). A concise Pahlavi Dictionary (p. 23, 16).

- "BAGHDAD i. Before the Mongol Invasion – Encyclopædia Iranica". Iranicaonline.org. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2013.

- Guy Le Strange, "Baghdad During the Abbasid Caliphate from Contemporary Arabic and Persian", pg 10

- Joneidi, F. (2007). متنهای پهلوی. In Pahlavi Script and Language (Arsacid and Sassanid) نامه پهلوانی: آموزش خط و زبان پهلوی اشکانی و ساسانی (second ed., p. 109). Tehran: Balkh (نشر بلخ).

- "Persimmons surviving winter in Bagdati, Georgia". Georgian Journal. 22 February 2016. Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- "Kutaisi". Archived from the original on 23 September 2016. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- John B. Friedman, Kristen M. Figg Trade, Travel, and Exploration in the Middle Ages, (Taylor & Francis, 2013)

- Brinkmann J. A. A political history of post-Kassite Babylonia, 1158-722 B.C.(Gregorian Biblical BookShop, 1968)

- "ما معنى اسم مدينة بغداد ومن سماه ؟". Seenjeem.maktoob.com. Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- "ما معنى (بغداد)؟ العراق العالم العربي الجغرافيا". Google Ejabat (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 29 December 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- Corzine, Phyllis (2005). The Islamic Empire. Thomson Gale. pp. 68–69.

- Times History of the World. London: Times Books. 2000.

- Wiet, Gastron (1971). Baghdad: Metropolis of the Abbasid Caliphate. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Tillier, Mathieu (2009). Les cadis d'Iraq et l'État Abbasside (132/750-334/945). Presses de l’Ifpo. ISBN 978-2-35159-028-7.

- Battuta, pg. 75

- Wiet 1971, p. 13.

- Corzine, Phyllis (2005). The Islamic Empire. Thomson Gale. p. 69.

- Wiet 1971, p. 12.

- "Abbasid Ceramics: Plan of Baghdad". Archived from the original on 25 March 2003. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- "Yakut: Baghdad under the Abbasids, c. 1000CE"

- Wiet 1971, p. 15.

- Hattstein, Markus; Peter Delius (2000). Islam Art and Architecture. Cologne: Könemann. p. 96. ISBN 978-3-8290-2558-4.

- Encyclopædia Iranica, Columbia University, p.413.

- Hill, Donald R. (1994). Islamic Science and Engineering. Edinburgh: Edinburgh Univ. Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7486-0457-9.

- Gordon, M.S. (2006). Baghdad. In Meri, J.W. ed. Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. New York: Routledge.

- When Baghdad was centre of the scientific world. The Guardian. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- "The population of Hira comprised its townspeople, the 'Ibad "devotees", who were Nestorian Christians using Syriac as their liturgical and cultural language, though Arabic was probably the language of daily intercourse." (1983). Yarshater, E. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran. doi:10.1017/chol9780521200929. ISBN 9781139054942.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- 1938-, Ohlig, Karl-Heinz, - The hidden origins of Islam: new research into its early history. Prometheus Books. p. 32. :"The 'Ibad are tribes made up of different Arabian families that became connected with Christianity in al-Hira." (2013). Early Islam. p. 32. ISBN 9781616148256. OCLC 914334282.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Beeston, A.F.L.; Shahîd, Irfan (2012). "al-ḤĪRA". In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_sim_2891.

- Meri, Josef (12 January 2018). Routledge Revivals: Medieval Islamic Civilization (2006). doi:10.4324/9781315162416. ISBN 9781315162416.

- "Sir Henry Lyons, F.R.S". Nature. 132 (3323): 55. July 1933. Bibcode:1933Natur.132S..55.. doi:10.1038/132055c0. ISSN 0028-0836.

- Pormann, Peter E. (2007). Medieval Islamic medicine. Savage-Smith, Emilie. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 9781589011601. OCLC 71581787.

- "syriacs during the islamic golden age - Google Search". www.google.com. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- HumWest (14 March 2015). "Baghdad in Its Golden Age (762-1300) | 25–26 April 2014". Humanities West. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- Falagas, Matthew E.; Zarkadoulia, Effie A.; Samonis, George (1 August 2006). "Arab science in the golden age (750–1258 C.E.) and today". The FASEB Journal. 20 (10): 1581–1586. doi:10.1096/fj.06-0803ufm. ISSN 0892-6638. PMID 16873881.

- Saliba, George (2007). Islamic Science and the Making of the European Renaissance. doi:10.7551/mitpress/3981.001.0001. ISBN 9780262282888.

- Lyons, Jonathan (2011). The House of Wisdom : How the Arabs Transformed Western Civilization. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 9781608191901. OCLC 1021808136.

- "Largest Cities Through History". Geography.about.com. 2 November 2009. Archived from the original on 27 May 2005. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- Matt T. Rosenberg, Largest Cities Through History. Archived 27 May 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- Mackensen, Ruth Stellhorn . (1932). Four Great Libraries of Medieval Baghdad. The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy, Vol. 2, No. 3 (July 1932), pp. 279-299. University of Chicago Press.

- George Modelski, World Cities: –3000 to 2000, Washington, D.C.: FAROS 2000, 2003. ISBN 978-0-9676230-1-6. See also Evolutionary World Politics Homepage Archived 20 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Trudy Ring; Robert M. Salkin; K. A. Berney; Paul E. Schellinger (1996). International dictionary of historic places, Volume 4: Middle East and Africa. Taylor and Francis. p. 116.

- Atlas of the Medieval World pg. 170

- Virani, Shafique N. The Ismailis in the Middle Ages: A History of Survival, A Search for Salvation, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 6.

- Daftary, Farhad. The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990, 205-206.

- Daftary, Farhad. The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990, 206.

- Central Asian world cities Archived 18 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, George Modelski

- Bosworth, C.E.; Donzel, E. van; Heinrichs, W.P.; Pellat, Ch., eds. (1998). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Volume VII (Mif-Naz). BRILL. p. 1032. ISBN 9789004094192.

- "Baghdad Sacked by the Mongols | History Today". www.historytoday.com. Archived from the original on 10 September 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- Cooper, William W.; Yue, Piyu (15 February 2008). Challenges of the Muslim World: Present, Future and Past. Emerald Group Publishing. ISBN 9780444532435. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- Michael R.T. Dumper; Bruce E. Stanley, eds. (2008), "Baghdad", Cities of the Middle East and North Africa, Santa Barbara, USA: ABC-CLIO

- Ian Frazier, Annals of history: Invaders: Destroying Baghdad Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, The New Yorker 25 April 2005. p.5

- New Book Looks at Old-Style Central Asian Despotism Archived 18 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine, EurasiaNet Civil Society, Elizabeth Kiem, 28 April 2006

- "The Fertile Crescent, 1800-1914: a documentary economic history". Charles Philip Issawi (1988). Oxford University Press US. p.99. ISBN 0-19-504951-9

- Suraiya Faroqhi, Halil İnalcık, Donald Quataert (1997). "An economic and social history of the Ottoman Empire". Cambridge University Press. p.651. ISBN 0-521-57455-2

- Cetinsaya, Gokhan. Ottoman Administration of Iraq, 1890–1908. London and New York: Routledge, 2006.

- Jackson, Iain (2 April 2016). "The architecture of the British Mandate in Iraq: nation-building and state creation". The Journal of Architecture. 21 (3): 375–417. doi:10.1080/13602365.2016.1179662. ISSN 1360-2365.

- Edmund A. Ghareeb; Beth Dougherty (18 March 2004). Historical Dictionary of Iraq. Scarecrow Press. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-8108-6568-6.

Jews represented 2.5 percent of 'Iraq's population and 25 percent of Baghdad's.

- Stanek, L., Miastoprojekt goes abroad: the transfer of architectural labour from socialist Poland to Iraq (1958–1989), The Journal of Architecture, Volume 17, Issue 3, 2012

- Spencer, Richard (22 December 2014). "Iraq crisis: The last Christians of Dora". Archived from the original on 13 April 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Owles, Eric (18 December 2008). "Then and Now: A New Chapter for Baghdad Book Market". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 December 2008. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- "The Choice, featuring Lawrence Anthony". BBC Radio 4. 4 September 2007. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2007.

- Anthony, Lawrence; Spence Grayham (3 June 2007). Babylon's Ark; The Incredible Wartime Rescue of the Baghdad Zoo. Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-0-312-35832-7.

- Makiya, K.; Al-Khalilm, S., The Monument: Art, Vulgarity, and Responsibility in Saddam Hussein's Iraq, p. 29

- "GlobalSecurity.org". Archived from the original on 25 December 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- Al-Qushla: Iraq's oasis of free expression. Archived 16 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine Al-Jazeera. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- 5880 Archived 4 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine. UNESCO. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- "تاریخچه حرم کاظمین" (in Persian). kazem.ommolketab.ir. Archived from the original on 10 March 2018. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- افتتاحية قبة الامام الجواد عليه السلام. www.aljawadain.org (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 13 August 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- البدء بإعمار وتذهيب قبة الإمام الكاظم عليه السلام. www.aljawadain.org (in Avestan). Archived from the original on 13 August 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2009.

- al-Aadhamy. History of the Great Imam mosque and al-Adhamiyah mosques 1. p. 29.

- Al Shakir, Osama S. (20 October 2013). "History of the Moof Abu Hanifa and its school". Abu Hanifa An-Nu'man Mosque. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 20 June 2017. (in Arabic)

- "Iraq: A Guide to the Green Zone". Newsweek. 17 December 2006. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- "New troops to move into Iraq". USA Today.

- "DefenseLink News Article: Soldier Helps to Form Democracy in Baghdad". Defenselink.mil. Archived from the original on 31 August 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- "Zafaraniya Residents Get Water Project Update - DefendAmerica News Article". Defendamerica.mil. Archived from the original on 28 December 2008. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- Frank, Thomas (26 March 2006). "Basics of democracy in Iraq include frustration". USA Today. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- "DefendAmerica News - Article". Defendamerica.mil. Archived from the original on 27 December 2008. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- "Democracy from scratch". csmonitor.com. 5 December 2003. Archived from the original on 3 April 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- "Leaders Highlight Successes of Baghdad Operation - DefendAmerica News Article". Defendamerica.mil. Archived from the original on 28 December 2008. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- "NBC 6 News - 1st Cav Headlines". Archived from the original on 12 December 2007.

- "Geert Jan van Oldenborgh @ KNMI". archive.is. 11 July 2012. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- "Climatologie mensuelle en juillet 2020 à Baghdad | climatologie depuis 1900 - Infoclimat". www.infoclimat.fr.

- Cappucci, Matthew; Salim, Mustafa (29 July 2020). "Baghdad Soars to 125 Blistering Degrees, Its Highest Temperature on Record". The Washington Post. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- "World Weather Information Service". worldweather.wmo.int. 26 October 2016. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- "Geert Jan van Oldenborgh @ KNMI". archive.is. 11 July 2012. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- (AFP) – 11 January 2008 (11 January 2008). "Afp.google.com, First snow for 100 years falls on Baghdad". Archived from the original on 29 September 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- "Ultra-rare snowfall carpets Baghdad". Bangkokpost.com. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- "World Weather Information Service - Baghdad". World Meteorological Organization. Archived from the original on 25 June 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2013.

- "Baghdad Climate Guide to the Average Weather & Temperatures, with Graphs Elucidating Sunshine and Rainfall Data & Information about Wind Speeds & Humidity". Climate & Temperature. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- "Monthly weather forecast and climate for Baghdad, Iraq". Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- Kamal, Nesrine (18 June 2016). "'Sushi' children defy Sunni-Shia divide". BBC News. Archived from the original on 10 October 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- "Iraqi Airways". Archived from the original on 18 May 2008. Retrieved 7 February 2016.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) Arab Air Carriers Organization. Retrieved on 19 October 2009.

- "ARCADD". Archived from the original on 20 December 2008.

- Goode, Erica; Mohammed, Riyadh (20 September 2008). "The New York Times". The New York Times. nytimes.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- Mohammed, Riyadh; Leland, John (29 December 2009). "The New York Times". The New York Times. nytimes.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- Yacoub, Sameer. "Baghdad plans to build giant Ferris wheel". NBC News. Retrieved 27 August 2008.

- "'Baghdad Eye' To Draw Tourists". Sky News. 28 August 2008. Archived from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2019.

- "Iraq plans giant Ferris wheel, hopes to lure tourists to Baghdad". Archived from the original on 1 December 2016. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- Wikinews: Iraq plans 'Baghdad Eye' to draw in tourists

- Jared Jacang Maher (October 2008). "Obama ad attacks McCain for Baghdad Ferris wheel project being built on land leased by a Democratic Party donor". Westword. Archived from the original on 14 January 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- AFP (21 March 2011). "New Ferris wheel attracts leisure-starved Iraqis". dawn.com. Archived from the original on 24 August 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- "Baghdad Gate". Iraqi News. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- "Baghdad Investment: Creating (1824) housing units in Baghdad". Baghdad Governorate Website. 2010. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- "Arrêté du 22 novembre 1990 complétant l'arrêté du 23 août 1990 fixant la liste des établissements d'enseignement prévue à l'article 1er du décret no 90-469 du 31 mai 1990" (Archive). Legislature of France. Retrieved on 12 March 2016.

- "Deutscher Bundestag 4. Wahlperiode Drucksache IV/3672" (Archive). Bundestag (West Germany). 23 June 1965. Retrieved on 12 March 2016. p. 35/51.

- "中近東の日本人学校一覧" (). National Education Center (国立教育会館) of Japan. 21 February 1999. Retrieved on 12 March 2016. "バクダッド 休 校 中 " (means "Baghdad School Closed")

- "Baghdad: The City in Verse, translated and edited by Reuven Snir". Harvard University Press. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Baghdad selected as new member of 'UNESCO Creative Cities Network'". Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- "Five women confront a new Iraq | csmonitor.com". Archived from the original on 28 August 2009.

- "In Baghdad, Art Thrives As War Hovers". Commondreams.org. 2 January 2003. Archived from the original on 27 June 2010. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- "Gunmen storm independent radio station in latest attack against media in Iraq". International Herald Tribune. 29 March 2009. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Occupation and international humanitarian law: Questions and answers - ICRC". 4 August 2004. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- "PowWeb" (PDF). dcswift.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- "Twinning the Cities". City of Beirut. Archived from the original on 21 February 2008. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- Corfield, Justin (2013). Historical Dictionary of Pyongyang. London: Anthem Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-85728-234-7.

Further reading

Articles

- By Desert Ways to Baghdad, by Louisa Jebb (Mrs. Roland Wilkins), 1908 (1909 ed) (a searchable facsimile at the University of Georgia Libraries; DjVu & "layered PDF" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2005. (11.3 MB) format)

- A Dweller in Mesopotamia, being the adventures of an official artist in the Garden of Eden, by Donald Maxwell, 1921 (a searchable facsimile at the University of Georgia Libraries; DjVu & "layered PDF" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2005. (7.53 MB) format)

- Miastoprojekt goes abroad: the transfer of architectural labour from socialist Poland to Iraq (1958–1989) by Lukasz Stanek, The Journal of Architecture, Volume 17, Issue 3, 2012

Books

- Pieri, Caecilia (2011). Baghdad Arts Deco: Architectural Brickwork, 1920-1950 (1st ed.). The American University in Cairo Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-9774163562.

- "Travels in Asia and Africa 1325-135" by Ibn Battuta

- "Gertrude Bell: the Arabian diaries,1913–1914." by Bell Gertrude Lowthian, and O'Brien, Rosemary.

- "Historic cities of the Islamic world."by Bosworth, Clifford Edmund.

- "Ottoman administration of Iraq, 1890–1908." by Cetinsaya, Gokhan.

- "Naked in Baghdad." by Garrels, Anne, and Lawrence, Vint.

- "A memoir of Major-General Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson." by Rawlinson, George.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baghdad. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Baghdad. |

| Look up Baghdad in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Bagdad (city). |

- Amanat/Mayoralty of Baghdad

- Map of Baghdad

- Iraq Image - Baghdad Satellite Observation

- National Commission for Investment in Iraq

- Interactive map

- Iraq - Urban Society

- - Baghdad government websites

- Envisioning Reconstruction In Iraq

- Description of the original layout of Baghdad

- Ethnic and sectarian map of Baghdad - Healingiraq

- UAE Investors Keen On Taking Part In Baghdad Renaissance Project

- Man With A Plan: Hisham Ashkouri

- Behind Baghdad's 9/11

- Iraq Inter-Agency Information & Analysis Unit Reports, maps and assessments of Iraq from the UN Inter-Agency Information & Analysis Unit

.jpg)