Mashallah ibn Athari

Mā Shā’ Allāh ibn Athari (Arabic: ما شاء الله إبن أثري)[1] (c.740–815 CE) was an eighth-century Persian Jewish[2] astrologer, astronomer, and mathematician. Originally from Khorasan[3] he lived in Basra (present day Iraq) during the reigns of al-Manṣūr and al-Ma’mūn, and was among those who introduced astrology and astronomy to Baghdād in the late 8th and early 9th century.[4] The bibliographer al-Nadim in his Fihrist, described him "as virtuous and in his time a leader in the science of jurisprudence, i.e. the science of judgments of the stars".[5] He served as a court astrologer for the Abbasid caliphate, and wrote numerous works on astrology in Arabic. Some Latin translations survive.

Masha'allah ibn Athari | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 740 |

| Died | 815 (aged 75) |

| Occupation | Astronomer |

The Arabic phrase ma sha`a allah indicates a believer's acceptance of God's ordainment of good or ill fortune. The name (Ma) Sha'a Allah is probably an Arabic rendering of Hebrew Sh'luh (Hebrew: שִׁילוה), which in is the name of the Messiah referenced in Genesis 49:10. Al-Nadim writes Mashallah's name 'Mīshā', means "yithro" (يثرو), which is probably the Hebrew name Jethro, from yithrā (“abundance”).[1] [6] Latin translators called him many variants such as Messahala, Messahalla, Messala, Macellama, Macelarma, Messahalah, etc. The crater Messala on the Moon is named after him.

Biography

| Astrology |

|---|

New millennium astrological chart |

| Background |

| Traditions |

| Branches |

As a young man he participated in the founding of Baghdad for Caliph al-Manṣūr in 762 by working with a group of astrologers led by Naubakht the Persian to pick an electional horoscope for the founding of the city[7] and building of an observatory.[8] Attributed the author of over twenty titles, predominantly on astrology, his authority was established over the centuries in the Middle East, and later in the West, when horoscopic astrology was transmitted to Europe from the 12th century. His writings include both what would be recognized as traditional horary astrology and an earlier type of astrology which casts consultation charts to divine the client's intention.[7] The strong influence of Hermes Trismegistus and Dorotheus is evident in his work.[9]

Works Listed in Kitab al-Fihrist

- The Big Book of Births (كتاب المواليد الكبير) (14vols); The Twenty-One On Conjunctions, Religions and Sects (الواحد والعشرين في قرانات والأديان والملل); The Projection of [Astrological] Rays (مطرح الشعاع); The Meaning (المعاني); Construction and Operation of Astrolabes (صنعة الإسطرلابات والعمل بها); The Armillary Sphere (ذات الحلق); Rains and Winds (الأمطار والرياح); The Two Arrows (السهمين); Book known as The Seventh & Decimal (Ch.1 - The Beginning of Actions (ابتداء الأعمال); Ch.2 - Averting What Is Predestined (على دفع التدبير); Ch.3 - On Questions (في المسائل); Ch.4 - Testimonies of the Stars (شهادات الكواكب); Ch.5 - Happenings (الحدوث); Ch.6 Movement and Indications of the Two Luminaries [sun & moon]) (تسيير النيرين وما يدلان عليه); The Letters (الحروف); The Sultan (السلطان); The Journey (السفر); Preceptions (الأسعار)[lower-alpha 1]; Nativities (المواليد); Revolution (Transfer) of the Years of Nativities (تحويل سني المواليد); Governments (Dynasties) and Sects (الدول والملل); Prediction (Judgement) Based on Conjunctions and Oppositions (الحكم على الاجتماعات والاستقبالات); The Sick (المرضى); Predictions (Judgements) Based On Constellations (Ṣūr)(الصور والحكم عليها);[1]

Mashallah's treatise De mercibus (On Prices) is the oldest known scientific work extant in Arabic [10] and the only work of his extant in its original Arabic.[11] Multiple translations into medieval Latin, [12] Byzantine Greek[13][14] and Hebrew were made.

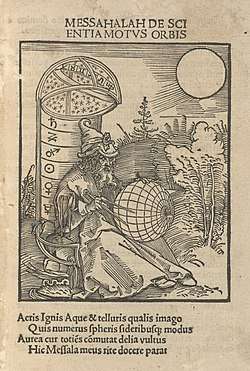

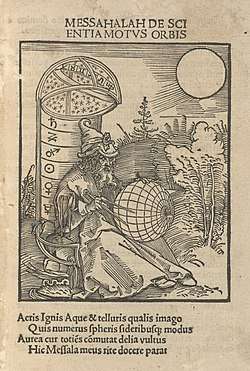

One of his most popular works in the Middle Ages was a cosmological treatise This comprehensive account of the cosmos along Aristotelian lines, covers many topics important to early cosmology. Postulating a ten-orb universe it strays from traditional cosmology. Mashallah aimed at the lay reader and illustrated his main ideas with comprehensible diagrams. Two versions of the manuscript were printed: a short version (27 chapters) De scientia motus orbis, and an expanded version (40 chapters) De elementis et orbibus.[5] The short version was translated by Gherardo Cremonese (Gerard of Cremona). Both were printed in Nuremberg, in 1504 and 1549, respectively. This work is commonly abbreviated to De orbe.

Chaucer's Source For Astrolabe Treatise

Mashallah's treatise on the astrolabe (p 10) is the first known of its kind.[9] Later translated from Arabic into Latin (De Astrolabii Compositione et Ultilitate). The exact source of Geoffrey Chaucer's Treatise on the Astrolabe (1391) in Middle English is undetermined but most of his ‘conclusions’ go back, directly or indirectly, to a Latin translation of Mashallah's work, called Compositio et Operatio Astrolabii. Chaucer's description of the instrument amplifies Mashallah’s, and his indebtedness was recognised by John Selden in 1613 [15] and established by Walter William Skeat. While Mark Harvey Liddell held that Chaucer drew on De Sphaera of John de Sacrobosco for the substantial part of his astronomical definitions and descriptions, the non-correspondence suggests his probable source was another compilation. Skeat's Treatise of the Astrolabe includes a collotype MS facsimile of the Latin version of the second part of Mashallah’s work, which parallels Chaucer's.[16] This is also found in R. T. Gunther's, Chaucer and Messahala on Astrology.[17] De elementis et orbibus was included in Gregor Reisch's Margarita phylosophica (ed. pr., Freiburg, 1503; Suter says the text is included in the Basel edition of 1583). Its contents primarily deal with the construction and usage of an astrolabe.

In 1981, Paul Kunitzsch argued that the treatise on the astrolabe long attributed to Mashallah is in fact written by Ibn al-Saffar.[18][19]

Texts & Translations

- On Conjunctions, Religions, and People was an astrological world history based on conjunctions of Jupiter and Saturn.[1] A few fragments are extant as quotations by the Christian astrologer Ibn Hibinta.[20]

- Liber Messahallaede revoltione liber annorum mundi, a work on revolutions, and De rebus eclipsium et de conjunctionibus planetarum in revolutionibus annorm mundi, a work on eclipses.

- Nativities under its Arabic title Kitab al - Mawalid, has been partially translated into English from a Latin translation of the Arabic[9]

- On Reception is available in English from the Latin edition by Joachim Heller of Nuremberg in 1549.[21]

Other astronomical and astrological writings are quoted by Suter and Steinschneider.

An Irish astronomical tract[22] appears based in part on a medieval Latin version of Mashallah. Two-thirds of tract are part-paraphrase part-translation.

The 12th-century scholar and astrologer Abraham ibn Ezra translated two of Mashallah's astrological treatises into Hebrew: She'elot and Ḳadrut (Steinschneider, "Hebr. Uebers." pp. 600–603).

Eleven modern translations of Mashallah's astrological treatises have been translated out of Latin into English.[7]

Philosophy

Mashallah postulated a ten-orb universe rather than the eight-orb model offered by Aristotle and the nine-orb model that was popular in his time. In all Mashallah's planetary model ascribes 26 orbs to the universe , which account for the relative positioning and motion of the seven planets. Of the ten orbs, the first seven contain the planets and the eighth contain the fixed stars. The ninth and tenth orbs were named by Mashallah the "Orb of Signs" and the "Great Orb", respectively. Both of these orbs are starless and move with the diurnal motion, but the tenth orb moves in the plane of the celestial equator while the ninth orb moves around poles that are inclined 24° with respect to the poles of the tenth orb. The ninth is also divided into twelve parts which are named after the zodiacal constellations that can be seen beneath them in the eighth orb. The eight and ninth orbs move around the same poles, but with different motion. The ninth orb moves with daily motion, so that the 12 signs are static with respect to the equinoxes, the eighth Orb of the Fixed Stars moves 1° in 100 years, so that the 12 zodiacal constellations are mobile with respect to the equinoxes.[5] The eight and ninth orbs moving around the same poles also guarantees that the 12 stationary signs and the 12 mobile zodiacal constellations overlap. By describing the universe in such a manner, Mashallah was attempting to demonstrate the natural reality of the 12 signs by stressing that the stars are located with respect to the signs and that fundamental natural phenomena, such as the beginning of the seasons, changes of weather, and the passage of the months, take place in the sublunar domain when the sun enters the signs of the ninth orb .[5]

Mashallah was an advocate of the idea that the conjunctions of Saturn and Jupiter dictate the timing of important events on Earth. These conjunctions, which occur about every twenty years, take place in the same triplicity for about two hundred years, and special significance is attached to a shift to another triplicity.[20]

Bibliography

- De cogitatione

- Epistola de rebus eclipsium et conjunctionibus planetarum (distinct from De magnis conjunctionibus by Abu Ma'shar al Balkhi ; Latin translation : John of Sevilla Hispalenis et Limiensis

- De revolutionibus annorum mundi

- De significationibus planetarum in nativitate

- Liber receptioni

- Works of Sahl and Masha'allah, trans. Benjamin Dykes, Cazimi Press, Golden Valley, MN, 2008.

- Masha'Allah, On Reception, trans. Robert Hand, ARHAT Publications, Reston, VA, 1998.

See also

- Liber de orbe

- Astrology in medieval Islam

- Jewish views of astrology

- List of Persian scientists and scholars

References

Footnotes

- Dodge notes that the Arabic word written al-as’ār (الأسعار) “prices”, should probably be al-ash’ār (الأشعار) “perceptions”: See Dodge, Bayard; The Fihrist of al

Citations

- Dodge, pp.650-651

- Syed, p.212

- Hill, p.10

- Pingree, pp.159–162.

- Sela, pp.101–134

- BEA, pp.740–1

- Dykes

- Dodge, p.653

- Lewis, pp.430–431

- Durant, p.403

- Pingree, pp.123–136

- Thorndike, pp.49–72

- Pingree, pp.231–243.

- Pingree, pp.3–37

- Selden, p.xliii

- Skeat, pp.88 ff.

- Gunther 1929

- Kunitzsch, Paul (1981). "On the authenticity of the treatise on the composition and use of the astrolabe ascribed to Messahalla". Archives Internationales d'Histoire des Sciences Oxford. 31 (106): 42–62.

- Selin, Helaine (2008-03-12). Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 1335. ISBN 978-1-4020-4559-2.

Paul Kunitzsch has recently established that the Latin treatise on the astrolabe long ascribed to Ma'sh'allah and translated by John of Seville is in fact by Ibn al-Saffar, a disciple of Maslama al-Majriti.

- Lorch, pp.438–439

- Hand

- Power

Bibliography

- Power, Afaula, ed. (1914), translated by Power, Afaula, "An Irish Astronomical Tract by Anon; Edited with Preface, Translation, and Glossary", Irish Texts Society, University College Cork, Ireland (Coláiste na hOllscoile Corcaigh), 14: 194

- Dodge, Bayard, ed. (1970), The Fihrist of Al-Nadim, A Tenth Century Survey of Muslim Culture, translated by Dodge, Bayard, New York & London: Columbia University Press, p. 650, 651, 655

- Drayton, Michael (1876), Hooper (ed.), John Seldon's Preface to Drayton's Polyolbion, 1 (Drayton’s Works ed.), London

- Durant, Will (1950), The Age of Faith: A History of Medieval Civilization – Christian, Islamic, and Judaic – from Constantine to Dante A.D. 325–1300, New York: Simon and Schuster

- Works of Sahl and Masha'allah, translated by Dykes, Benjamin N, Cazimi Press, 2008, archived from the original on 2009-11-14, retrieved 2015-05-14

- "The Encyclopedia of Heavenly Influences", The Astrology Book, Visible Ink Press, 2003

- Gunther, R T (1929), "Chaucer and Messahalla on the Astrolabe", Early Science in Oxford, Oxford, 5

- On Reception (by Masha'allah), translated by Hand, Robert, Archive for the Retrieval of Historical Astrological Texts, 1998, archived from the original on 2007-10-02, retrieved 2009-03-15

- Hill, Donald R (1994), "Islamic Science and Engineering", Dictionary of Scientific Biography, ISBN 0-7486-0457-X

- Hockey, Thomas; Belenkiy, Ari, eds. (2007), "Māshāʾallāh ibn Atharī (Sāriya)", The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers, New York: Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0

- Holden, James (1996), A History of Horoscopic Astrology, American Federation of Astrologers, Tempe, AZ., pp. 104–107, ISBN 0-86690-463-8

- Lorch, R.P. (September 2013), "The Astrological History of Māshā'allāh", The British Journal for the History of Science, Cambridge, Mass: Cambridge University Press, 6 (4), doi:10.1017/s0007087400012644

- "Mashallah", Letter 2052, Astronomy, Jewish Encyclopedia

- Pingree, David (1974), "Māshā'allāh", Dictionary of Scientific Biography, American Federation of Astrologers, Tempe, AZ., 9

- Pingree, David (1997), "Māshā'allāh: Greek, Pahlavī, Arabic, and Latin Astrology", Perspectives arabes et médiévales sur la tradition scientifique et philosophique grecque, Leuven-Paris: Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta, 79

- Pingree, David (2006), Magdalino, Paul; Mavroudi, Maria V (eds.), "The Byzantine Translations of Māshā'allāh on Interrogational Astrology", The Occult Sciences in Byzantium, Geneva

- Pingree, David (2001), "From Alexandria to Baghdād to Byzantium: The Transmission of Astrology", International Journal of the Classical Tradition, 8 (Summer): 3–37, doi:10.1007/BF02700227

- Qiftī (al-), Jamāl al-Dīn Abū al-Ḥasan ‘Alī ibn Yūsuf (1903), Lippert, Julius; Weicher, Theodor (eds.), Tarīkh al-Ḥukamā, Leipzig, p. 327

- Sarton, George (1927), Introduction to the History of Science, 1 (1948 ed.), Baltimore: The Carnegie Institution of Washington, Williams and Wilkins, p. 531

- Sela, Shlomo (2012), "Maimonides and Mashallah on the Ninth Orb of the Signs and Astrology", Historical Studies in Science and Judaism, Indiana University: Aleph, 12 (1): 101–134, doi:10.2979/aleph.12.1.101, retrieved 3 Nov 2013

- Skeat, Walter William (1872), Chaucer's A Treatise on the Astrolabe, Chaucer Society

- Suter, Hienrich (1892), "Die Mathematiker und Astronom der Araber und ihre Werke", Abhandlungen zur Geschichte der Mathematik, Leipzig: Teubner, VI, p. 27, 61

- Ibid., X, 1900, p. 3, 277

- Syed, M. H., Islam and Science, p. 212

- Thorndike, Lynn (1956), "The Latin Translations of Astrological Works by Messahala", Osiris, 12 (12): 49–72, doi:10.1086/368596

- Ṭūqān, Qudrī Ḥāfiẓ (1963), Turāth al-'Arab al-'Ilmī fī al-Riyāḍīyāt wa-al-Falak (Arab League Publication ed.), Cairo: Dār al-Qalam, p. 112, 135, ISBN 0-19-281157-6

External links

- Belenkiy, Ari (2007). "Māshāʾallāh ibn Atharī (Sāriya)". In Thomas Hockey; et al. (eds.). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 740–1. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0. (PDF version)

- Blog, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries Pseudo-Masha’Allah, On the Astrolabe, ed. Ron B. Thomson, version 1.0 (Toronto, 2012); A Critical Edition of the Latin Text with English Translation by Ron B. Thomson.