Uto-Aztecan languages

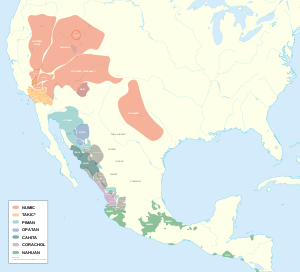

Uto-Aztecan or Uto-Aztekan /ˈjuːtoʊ.æzˈtɛkən/ is a family of indigenous languages of the Americas, consisting of over 30 languages. Uto-Aztecan languages are found almost entirely in the Western United States and Mexico. The name of the language family was created to show that it includes both the Ute language of Utah and the Nahuan languages (also known as Aztecan) of Mexico.

| Uto-Aztecan | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Western United States, Mexico |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families |

| Proto-language | Proto-Uto-Aztecan |

| Subdivisions | |

| ISO 639-5 | azc |

| Glottolog | utoa1244[1] |

Pre-contact distribution of Uto-Aztecan languages. | |

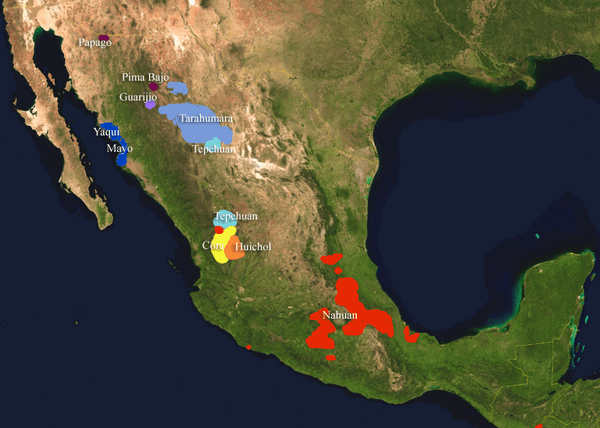

_map_(colors_adjusted).svg.png) Current extent of Uto-Aztecan languages in Mexico | |

The Uto-Aztecan language family is one of the largest linguistic families in the Americas in terms of number of speakers, number of languages, and geographic extension.[2] The northernmost Uto-Aztecan language is Shoshoni, which is spoken as far north as Salmon, Idaho, while the southernmost is the Pipil language of El Salvador. Ethnologue gives the total number of languages in the family as 61, and the total number of speakers as 1,900,412.[3] The roughly 1.7-1.9 million speakers of Nahuatl languages account for almost four-fifths (78.9%) of these.

The internal classification of the family often divides the family into two branches: a northern branch including all the languages of the US and a Southern branch including all the languages of Mexico, although it is still being discussed whether this is best understood as a genetic classification or as a geographical one. Below this level of classification the main branches are well accepted: Numic (including languages such as Comanche and Shoshoni) and the Californian languages (formerly known as the Takic group, including Cahuilla and Luiseño) account for most of the Northern languages. Hopi and Tübatulabal are languages outside those groups. The Southern languages are divided into the Tepiman languages (including O'odham and Tepehuán), the Tarahumaran languages (including Raramuri and Guarijio), the Cahitan languages (including Yaqui and Mayo), the Coracholan languages (including Cora and Huichol), and the Nahuan languages.

The homeland of the Uto-Aztecan languages is generally considered to have been in the Southwestern United States or possibly Northwestern Mexico. An alternative theory has proposed the possibility that the language family originated in southern Mexico, within the Mesoamerican language area, but this has not been generally considered convincing.

Geographic distribution

Uto-Aztecan languages are spoken in the North American mountain ranges and adjacent lowlands of the western United States (in the states of Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Utah, California, Nevada, Arizona) and of Mexico (states of Sonora, Chihuahua, Nayarit, Durango, Zacatecas, Jalisco, Michoacán, Guerrero, San Luis Potosí, Hidalgo, Puebla, Veracruz, Morelos, Estado de México, and Ciudad de México. Classical Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, and its modern relatives are part of the Uto-Aztecan family. The Pipil language, an offshoot of Nahuatl, spread to Central America by a wave of migration from Mexico, and formerly had many speakers there. Now it has gone extinct in Guatemala and Honduras, and it is nearly extinct in western El Salvador, all areas dominated by use of Spanish.

- Uto-Aztecan-speaking communities in and around Mexico

Classification

History of classification

Uto-Aztecan has been accepted by linguists as a language family since the early 1900s, and six subgroups are generally accepted as valid: Numic, Takic, Pimic, Taracahitic, Corachol, and Aztecan. That leaves two ungrouped languages: Tübatulabal and Hopi (sometimes termed "isolates within the family"). Some recent studies have begun to question the unity of Taracahitic and Takic and computer-assisted statistical studies have begun to question some of the long-held assumptions and consensuses. As to higher-level groupings, disagreement has persisted since the 19th century. Presently scholars also disagree as to where to draw language boundaries within the dialect continua.

The similarities among the Uto-Aztecan languages were noted as early as 1859 by J. C. E. Buschmann, but he failed to recognize the genetic affiliation between the Aztecan branch and the rest. He ascribed the similarities between the two groups to diffusion. Daniel Garrison Brinton added the Aztecan languages to the family in 1891 and coined the term Uto-Aztecan. John Wesley Powell, however, rejected the claim in his own classification of North American indigenous languages (also published in 1891). Powell recognized two language families: "Shoshonean" (encompassing Takic, Numic, Hopi, and Tübatulabal) and "Sonoran" (encompassing Pimic, Taracahitan, and Corachol). In the early 1900s Alfred L. Kroeber filled in the picture of the Shoshonean group,[4] while Edward Sapir proved the unity among Aztecan, "Sonoran", and "Shoshonean".[5][6][7] Sapir's applications of the comparative method to unwritten Native American languages are regarded as groundbreaking. Voegelin, Voegelin & Hale (1962) argued for a three-way division of Shoshonean, Sonoran and Aztecan, following Powell.[8]

As of about 2011, there is still debate about whether to accept the proposed basic split between "Northern Uto-Aztecan" and "Southern Uto-Aztecan" languages.[2] Northern Uto-Aztecan corresponds to Powell's "Shoshonean", and the latter is all the rest: Powell's "Sonoran" plus Aztecan. Northern Uto-Aztecan was proposed as a genetic grouping by Jeffrey Heath in Heath (1978) based on morphological evidence, and Alexis Manaster Ramer in Manaster Ramer (1992) adduced phonological evidence in the form of a sound law. Terrence Kaufman in Kaufman (1981) accepted the basic division into Northern and Southern branches as valid. Other scholars have rejected the genealogical unity of either both nodes or the Northern node alone.[9][10][11][12] Wick R. Miller's argument was statistical, arguing that Northern Uto-Aztecan languages displayed too few cognates to be considered a unit. On the other hands he found the number of cognates among Southern Uto-Aztecan languages to suggest a genetic relation.[11] This position was supported by subsequent lexicostatistic analyses by Cortina-Borja & Valiñas-Coalla (1989) and Cortina-Borja, Stuart-Smith & Valiñas-Coalla (2002). Reviewing the debate, Haugen (2008) considers the evidence in favor of the genetic unity of Northern Uto-Aztecan to be convincing, but remains agnostic on the validity of Southern Uto-Aztecan as a genetic grouping. Hill (2011) also considered the North/South split to be valid based on phonological evidence, confirming both groupings. Merrill (2013) adduced further evidence for the unity of Southern Uto-Aztecan as a valid grouping.

Hill (2011) also rejected the validity of the Takic grouping decomposing it into a Californian areal grouping together with Tubatulabal.

Some classifications have posited a genetic relation between Corachol and Nahuan (e.g. Merrill (2013)). Kaufman recognizes similarities between Corachol and Aztecan, but explains them by diffusion instead of genetic evolution.[13] Most scholars view the breakup of Proto-Uto-Aztecan as a case of the gradual disintegration of a dialect continuum.[14]

Present scheme

Below is a representation of the internal classification of the language family based on Shaul (2014). The classification reflects the decision to split up the previous Taracahitic and Takic groups, that are no longer considered to be valid genetic units. Whether the division between Northern and Southern languages is best understood as geographical or phylogenetic is under discussion. The table contains demographic information about number of speakers and their locations based on data from The Ethnologue. The table also contains links to a selected bibliography of grammars, dictionaries on many of the individual languages.(† = extinct)

| Genealogical classification of Uto-Aztecan languages | ||||||

| Family | Groups | Languages | Where spoken and approximate number of speakers | Works | ||

| Uto-Aztecan languages | Northern Uto-Aztecan (possibly an areal grouping) |

Numic | Western Numic | Paviotso, Bannock, Northern Paiute | 700 speakers in California, Oregon, Idaho and Nevada | Nichols (1973) |

| Mono | About 40 speakers in California | Lamb (1958) | ||||

| Central Numic | ||||||

| Shoshoni, Goshiute | 1000 fluent speakers and 1000 learners in Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, Idaho | McLaughlin (2012) | ||||

| Comanche | 100 speakers in Oklahoma | Robinson & Armagost (1990) | ||||

| Timbisha, Panamint | 20 speakers in California and Nevada | Dayley (1989) | ||||

| Southern Numic | Colorado River dialect chain: Ute, Southern Paiute, Chemehuevi | 920 speakers of all dialects, in Colorado, Nevada, California, Utah, Arizona | Givón (2011), Press (1979), Sapir (1992) | |||

| Kawaiisu | 5 speakers in California | Zigmond, Booth & Munro (1991) | ||||

| Californian language area | Serran | Serrano, Kitanemuk (†) | No native speakers | Hill (1967) | ||

| Cupan | Cahuilla, Cupeño | 35 speakers of Cahuilla, no native speakers of Cupeño | Seiler (1977), Hill (2005) | |||

| Luiseño-Juaneño | 5 speakers in Southern California | Kroeber & Grace (1960) | ||||

| Tongva (Gabrielino-Fernandeño) | Last native speakers died in early 1900s, in 21st century undergoing revival efforts, Southern California | Munro & Gabrielino/Tongva Language Committee (2008) | ||||

| Hopi | Hopi | 6,800 speakers in northeastern Arizona | Hopi Dictionary Project (1998), Jeanne (1978) | |||

| Tübatulabal | Tübatulabal | 5 speakers in Kern County, California | Voegelin (1935), Voegelin (1958) | |||

| Southern Uto-Aztecan (possibly an areal grouping) |

Tepiman | |||||

| Pimic | O'odham (Pima-Papago) | 14,000 speakers in southern Arizona, US and northern Sonora, Mexico | Zepeda (1983) | |||

| Pima Bajo (O'ob No'ok) | 650 speakers in Chihuahua and Sonora, Mexico | Estrada-Fernández (1998) | ||||

| Tepehuan | Northern Tepehuan | 6,200 speakers in Chihuahua, Mexico | Bascom (1982) | |||

| Southern Tepehuan | 10,600 speakers in Southeastern Durango | Willett (1991) | ||||

| Tepecano (†) | Extinct since approx. 1985, spoken in Northern Jalisco | Mason (1916) | ||||

| Tarahumaran | Tarahumara (several varieties) | 45,500 speakers of all varieties, all spoken in Chihuahua | Caballero (2008) | |||

| Upriver Guarijio, Downriver Guarijio | 2,840 speakers in Chihuahua and Sonora | Miller (1996) | ||||

| Tubar (†) | Spoken in Sinaloa and Sonora | Lionnet (1978) | ||||

| Cahita | Yaqui | 11,800 in Sonora and Arizona | Dedrick & Casad (1999) | |||

| Mayo | 33,000 in Sinaloa and Sonora | Freeze (1989) | ||||

| Opatan | Opata (†) | Extinct since approx. 1930. Spoken in Sonora. | Shaul (2001) | |||

| Eudeve (†) | Spoken in Sonora, but extinct since 1940 | Lionnet (1986) | ||||

| Corachol | Cora | 13,600 speakers in northern Nayarit | Casad (1984) | |||

| Huichol | 17,800 speakers in Nayarit and Jalisco | Iturrioz Leza & Ramírez de la Cruz (2001) | ||||

| Aztecan (Nahuan) | Pochutec (†) | Extinct since 1970s, spoken on the coast of Oaxaca | Boas (1917) | |||

| Core Nahuan | Pipil | 20-40 speakers in El Salvador | Campbell (1985) | |||

| Nahuatl | 1,500,000 speakers in Central Mexico | Launey (1986), Langacker (1979) | ||||

In addition to the above languages for which linguistic evidence exists, it is suspected that among dozens of now extinct, undocumented or poorly known languages of northern Mexico, many were Uto-Aztecan.[15]

Extinct languages

A large number of languages known only from brief mentions are thought to have been Uto-Aztecan languages that became extinct before being documented.[16]

Proto-Uto-Aztecan

| Proto-Uto-Aztecan | |

|---|---|

| PUA | |

| Reconstruction of | Uto-Aztecan languages |

| Region | Aridoamerica |

| Era | 3,000 BCE |

| Lower-order reconstructions | |

Proto-Uto-Aztecan is the hypothetical common ancestor of the Uto-Aztecan languages. Authorities on the history of the language group have usually placed the Proto-Uto-Aztecan homeland in the border region between the United States and Mexico, namely the upland regions of Arizona and New Mexico and the adjacent areas of the Mexican states of Sonora and Chihuahua, roughly corresponding to the Sonoran Desert and the western part of the Chihuahuan Desert. It would have been spoken by Mesolithic foragers in Aridoamerica, about 5,000 years ago.

References

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Uto-Aztecan". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Caballero 2011.

- Ethnologue (2014). "Summary by language family". SIL International. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- Kroeber 1907.

- Sapir 1913.

- Kroeber 1934.

- Whorf 1935.

- Steele 1979.

- Goddard 1996, p. 7.

- Miller 1983, p. 118.

- Miller 1984.

- Mithun 1999, p. 539-540.

- Kaufman 2001, .

- Mithun 1999.

- Campbell 1997.

- Campbell 1997, pp. 133–135.

Sources

- Brown, Cecil H. (2010). "Lack of linguistic support for Proto-Uto-Aztecan at 8900 BP (letter)". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107 (15): E34, author reply E35–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914859107. PMC 2841887. PMID 20231478.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Caballero, G. (2011). "Behind the Mexican Mountains: Recent Developments and New Directions in Research on Uto‐Aztecan Languages". Language and Linguistics Compass. 5 (7): 485–504. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818x.2011.00287.x.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Campbell, Lyle (1997). American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Campbell, Lyle (2003). "What drives linguistic diversification and language spread?". In Bellwood, Peter; Renfrew, Colin (eds.). Examining the farming/language dispersal hypothesis. Cambridge(U.K.): McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research. pp. 49–63.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Campbell, Lyle; Poser, William J. (2008). Language classification, history and method. Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cortina-Borja, M; Valiñas-Coalla, L (1989). "Some remarks on Uto-Aztecan Classification". International Journal of American Linguistics. 55 (2): 214–239. doi:10.1086/466114.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cortina-Borja, M.; Stuart-Smith, J.; Valiñas-Coalla, L. (2002). "Multivariate classification methods for lexical and phonological dissimilarities and their application to the Uto-Aztecan family". Journal of Quantitative Linguistics. 9 (2): 97–124. doi:10.1076/jqul.9.2.97.8485.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dakin, Karen (1996). "Long vowels and morpheme boundaries in Nahuatl and Uto-Aztecan: comments on historical developments" (PDF). Amerindia. 21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fowler, Catherine S. (1983). "Some lexical clues to Uto-Aztecan prehistory". International Journal of American Linguistics. 49 (3): 224–257. doi:10.1086/465789.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goddard, Ives (1996). "Introduction". In Goddard, Ives (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians. 17. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 1–16.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Haugen, J. D. (2008). Morphology at the interfaces: reduplication and noun incorporation in Uto-Aztecan. Vol. 117. John Benjamins Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heath, J. (1978). "Uto-Aztecan* na-class verbs". International Journal of American Linguistics. 44 (3): 211–222. doi:10.1086/465546.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hill, Jane H. (December 2001). "Proto-Uto-Aztecan". American Anthropologist. New Series. 103 (4): 913–934. doi:10.1525/aa.2001.103.4.913. JSTOR 684121.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hill, Jane H. (2010). "New evidence for a Mesoamerican homeland for Proto-Uto-Aztecan". PNAS. 107 (11): E33, author reply E35–6. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107E..33H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0914473107. PMC 2841890. PMID 20231477.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hill, J. H. (2011). "Subgrouping in Uto-Aztecan". Language Dynamics and Change. 1 (2): 241–278. doi:10.1163/221058212x643978.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Iannucci, David (1972). Numic historical phonology. Cornell University PhD dissertation.

- Kaufman, Terrence (2001). Nawa linguistic prehistory. Mesoamerican Language Documentation Project.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kaufman, Terrence (1981). Lyle Campbell (ed.). Comparative Uto-Aztecan Phonology. Unpublished manuscript.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kemp; González-Oliver; Malhi; Monroe; Schroeder; McDonough; Rhett; Resendéz; Peñalosa-Espinoza; Buentello-Malo; Gorodetsky; Smith (2010). "Evaluating the farming/language dispersal hypothesis with genetic variation exhibited by populations in the Southwest and Mesoamerica". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107 (15): 6759–6764. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.6759K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0905753107. PMC 2872417. PMID 20351276.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kroeber, Alfred Louis (1907). Shoshonean dialects of California. The University Press. Retrieved 24 August 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kroeber, Alfred Louis (1934). Uto-Aztecan Languages of Mexico. 8. University of California Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Langacker, Ronald W. (1970). "The Vowels of Proto Uto-Aztecan". International Journal of American Linguistics. 36 (3): 169–180. doi:10.1086/465108.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Langacker, R. W. (1977). An overview of Uto-Aztecan grammar. Summer Institute of Linguistics.

- Langacker, R. W. (1976). Non-distinct arguments in Uto-Aztecan. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Manaster Ramer, Alexis (1992). "A Northern Uto-Aztecan Sound Law: *-c- → -y-¹". International Journal of American Linguistics. 58 (3): 251–268. doi:10.1086/ijal.58.3.3519784. JSTOR 3519784.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Merrill, William L.; Hard, Robert J.; Mabry, Jonathan B.; Fritz; Adams; Roney; MacWilliams (2010). "Reply to Hill and Brown: Maize and Uto-Aztecan cultural history". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107 (11): E35–E36. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107E..35M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1000923107. PMC 2841871.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Merrill, W (2013). "The genetic unity of southern Uto-Aztecan". Language Dynamics and Change. 3: 68–104. doi:10.1163/22105832-13030102.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Merrill, William L. (2012). "The Historical Linguistics of Uto-Aztecan Agriculture". Anthropological Linguistics. 54 (3): 203–260. doi:10.1353/anl.2012.0017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miller, Wick R. (1986). "Numic Languages". In Warren L. d’Azevedo (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 11, Great Basin. Washington: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 98–106.

- Miller, Wick R. (1983). "A note on extinct languages of northwest Mexico of supposed Uto-Aztecan affiliation". International Journal of American Linguistics. 49 (3): 328–333. doi:10.1086/465793.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miller, Wick R. (1983). "Uto-Aztecan languages". In Ortiz, Alfonso (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians. 10. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 113–124.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miller, Wick R. (1984). "The classification of the Uto-Aztecan languages based on lexical evidence". International Journal of American Linguistics. 50 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1086/465813.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mithun, Marianne (1999). The languages of Native America. Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sapir, E. (1913). "Southern Paiute and Nahuatl, a study in Uto-Aztekan". Journal de la Société des Américanistes. 10 (2): 379–425. doi:10.3406/jsa.1913.2866.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shaul, David L. (2014). A Prehistory of Western North America: The Impact of Uto-Aztecan Languages. University of New Mexico Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shaul, David L.; Hill, Jane H. (1998). "Tepimans, Yumans, and other Hohokam". American Antiquity. 63 (3): 375–396. doi:10.2307/2694626. JSTOR 2694626.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Steele, Susan (1979). "Uto-Aztecan: An assessment for historical and comparative linguistics". In Campbell, Lyle; Mithun, Marianne (eds.). The Languages of Native America: Historical and Comparative Assessment. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 444–544.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Voegelin, C. F.; Voegelin, F.; Hale, K. (1962). Typological and Comparative Grammar of Uto-Aztecan: Phonology. Memoirs of the International Journal of American Linguistics. 17. Waverly Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whorf, B. L. (1935). "The Comparative Linguistics of Uto-Aztecan". American Anthropologist. 37 (4): 600–608. doi:10.1525/aa.1935.37.4.02a00050.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Individual languages

- Boas, Franz (1917). "El dialecto mexicano de Pochutla, Oaxaca". International Journal of American Linguistics (in Spanish). 1 (1): 9–44. doi:10.1086/463709. OCLC 56221629.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hopi Dictionary Project (1998). Hopi Dictionary: Hopìikwa Lavàytutuveni: A Hopi–English Dictionary of the Third Mesa Dialect With an English–Hopi Finder List and a Sketch of Hopi Grammar. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Campbell, Lyle (1985). The Pipil Language of El Salvador. Mouton Grammar Library, no. 1. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-010344-1. OCLC 13433705. Archived from the original on 2014-06-06. Retrieved 2014-06-06.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dayley, Jon P. (1989). "Tümpisa (Panamint) Shoshone Grammar". University of California Publications in Linguistics. 115.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Givón, Talmy (2011). Ute Reference Grammar. Culture and Language Use Volume 3. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jeanne, LaVerne Masayesva (1978). Aspects of Hopi grammar. MIT, dissertation.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Voegelin, Charles F. (1935). "Tübatulabal Grammar". University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology. 34: 55–190.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Voegelin, Charles F. (1958). "Working Dictionary of Tübatulabal". International Journal of American Linguistics. 24 (3): 221–228. doi:10.1086/464459.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robinson, Lila Wistrand; Armagost, James (1990). Comanche dictionary and grammar. publications in linguistics (No. 92). Dallas, Texas: The Summer Institute of Linguistics and The University of Texas at Arlington.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lamb, Sydney M (1958). A Grammar of Mono (PDF). PhD Dissertation, University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved July 8, 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zigmond, Maurice L.; Booth, Curtis G.; Munro, Pamela (1991). Pamela Munro (ed.). Kawaiisu, A Grammar and Dictionary with Texts. University of California Publications in Linguistics. Volume 119. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nichols, Michael (1973). Northern Paiute historical grammar. University of California, Berkeley PhD dissertation.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McLaughlin, John E. (2012). Shoshoni Grammar. Languages of the World/Meterials 488. Muenchen: LINCOM Europa.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Press, Margaret L. (1979). Chemehuevi, A Grammar and Lexicon. University of California Publications in Linguistics. Volume 92. Berkeley, California: University of California Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sapir, Edward (1992) [1930]. "Southern Paiute, a Shoshonean Language". In William Bright (ed.). The Collected Works of Edward Sapir, X, Southern Paiute and Ute Linguistics and Ethnography. Berlin: Mouton deGruyter.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Seiler, Hans-Jakob (1977). Cahuilla Grammar. Banning, California: Malki Museum Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hill, Kenneth C. (1967). A Grammar of the Serrano Language. University of California, Los Angeles, PhD dissertation.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hill, Jane H. (2005). A Grammar of Cupeño. University of California Publications in Linguistics. Berkeley: University of California Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Caballero, Gabriela (2008). Choguita Rarámuri (Tarahumara) Phonology and Morphology (PDF). PhD Dissertation: University of California at Berkeley.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thornes, Tim (2003). A Northern Paiute Grammar with Texts. PhD Dissertation: University of Oregon at Eugene.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kroeber, Alfred L.; Grace, George William (1960). The Sparkman Grammar of Luiseño. University of California Publications in Linguistics 16. Berkeley: The University of California Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zepeda, Ofelia (1983). A Tohono O'odham Grammar. Tucson, Arizona: The University of Arizona Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Willett, T. (1991). A reference grammar of southeastern Tepehuan (PDF). Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics and University of Texas at Arlington.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mason, J. Alden (1916). "Tepecano, A Piman language of western Mexico". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 25 (1): 309–416. Bibcode:1916NYASA..25..309M. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1916.tb55171.x. hdl:2027/uc1.c077921598.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miller, Wick R. (1996). La lengua guarijio: gramatica, vocabulario y textos. Mexico City: Instituto de Investigaciones Antropologicas, UNAM.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bascom, Burton W. (1982). "Northern Tepehuan". In Ronald W. Langacker (ed.). Studies in Uto-Aztecan Grammar, Volume 3, Uto-Aztecan Grammatical Sketches. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics and the University of Texas at Arlington. pp. 267–393.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lionnet, Andrés (1978). El idioma tubar y los tubares. Segun documentos ineditos de C. S. Lumholtz y C. V. Hartman. Mexico, D. F: Universidad Iberoamericana.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Casad, Eugene H. (1984). "Cora". In Ronald W. Langacker (ed.). Studies in Uto-Aztecan grammar 4: Southern Uto-Aztecan grammatical sketches. Summer Institute of Linguistics Publications in Linguistics 56. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics and the University of Texas at Arlington. pp. 153–149.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Iturrioz Leza, José Luis; Ramírez de la Cruz, Julio (2001). Gramática Didáctica del Huichol: Vol. I. Estructura Fonológica y Sistema de Escritura. Departamento de Estudios en Lenguas Indígenas–Universidad de Guadalajara – Secretaria de Educación Pública.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dedrick, John; Casad, Eugene H. (1999). Sonora Yaqui Language Structures. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 9780816519811.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Freeze, Ray A. (1989). Mayo de Los Capomos, Sinaloa. Archivo de Lenguas Indígenas del Estado de Oaxaca, 14. 14. 166. México, D.F.: Instituto de Investigación e Integración Social del Estado de Oaxaca.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lionnet, Andrés (1986). Un idioma extinto de sonora: El eudeve. México: UNAM. ISBN 978-968-837-915-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Estrada-Fernández, Zarina (1998). Pima bajo de Yepachi, Chihuahua. Archivo de Lenguas Indigenas de Mexico. Colegio de México.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Munro, Pamela; Gabrielino/Tongva Language Committee (2008). Yaara' Shiraaw'ax 'Eyooshiraaw'a. Now You're Speaking Our Language: Gabrielino/Tongva/Fernandeño. Lulu.com.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Launey, Michel (1986). Categories et operations dans la grammaire Nahuatl. Ph. D. dissertation, Paris IV.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Langacker, Ronald W. (ed.) (1979). Studies in Uto-Aztecan Grammar 2: Modern Aztec Grammatical Sketches. Summer Institute of Linguistics Publications in Linguistics, 56. Dallas, TX: Summer Institute of Linguistics and the University of Texas at Arlington. ISBN 978-0-88312-072-9.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shaul, D. L. (2001). The Opatan Languages, Plus Jova. Festschrift. INAH.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wiktionary has a list of reconstructed forms at Appendix:Proto-Uto-Aztecan reconstructions |

- Uto-Aztecan.org, a website devoted to the comparative study of the Uto-Aztecan language family

- Swadesh vocabulary lists for Uto-Aztecan languages (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

.svg.png)