Guanahatabey language

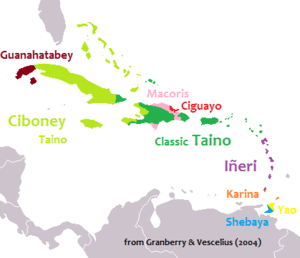

Guanahatabey (Guanajatabey) was the language of the Guanahatabey people, a hunter-gatherer society that lived in western Cuba until the 16th century. Very little is known of it, as the Guanahatabey died off early in the period of Spanish colonization before substantial information about them was recorded. Evidence suggests it was distinct from the Taíno language spoken in the rest of the island.[1][2]

| Guanahatabey | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Cuba |

| Region | Pinar del Río Province and Isla de la Juventud |

| Ethnicity | Guanahatabey |

| Extinct | 16th century |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

| Glottolog | None |

| |

Background

The Guanahatabey were hunter-gatherers that appear to have predated the agricultural Ciboney, the Taíno group that inhabited most of Cuba. By the contact period, the Guanahatabey lived primarily in far western Pinar del Río Province, which the Ciboney did not settle and was colonized by the Spanish relatively late. Spanish accounts indicate that Guanahatabey was distinct from and mutually unintelligible with the Taíno language spoken in the rest of Cuba and throughout the Caribbean.[1][3] Not a single word of the Guanahatabey language has been documented.

Toponyms

However, Julian Granberry and Gary Vescelius have identified five placenames that they consider non-Taíno, and which may thus derive from Guanahatabey. Granberry and Vescelius argue that the names have parallels in the Warao language, and further suggest a possible connection with the Macoris language of Hispaniola (see Waroid languages).[4]

| Name | Warao parallel | Warao meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Camujiro | ka-muhi-ru | 'palm-tree trunks' |

| Guara | wara | 'white heron' |

| Guaniguaníco (mountain range in western Cuba) | wani-wani-ku | 'hidden moon, moon-set' |

| Hanábona (a savannah) | hana-bana | 'sugarcane plumes' |

| Júcaro (three locations) | hu-karo | 'double pointed, tree crotch' |

Notes

- Rouse, pp. 20–21.

- Granberry and Vescelius, pp. 18–20.

- Granberry and Vescelius, pp. 15, 18–19.

- Granberry and Vescelius, pp. 75–77.

- Granberry and Vescelius, p. 76, Table 6

References

- Granberry, Julian; Vescelius, Gary (1992). Languages of the Pre-Columbian Antilles. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 081735123X.

- Rouse, Irving (1992). The Tainos. Yale University Press. p. 40. ISBN 0300051816.