Turanism

Turanism, also known as pan-Turanianism or pan-Turanism, is a nationalist cultural and political movement born in the 19th century to counter the effects of pan-nationalist ideologies such as pan-Germanism and pan-Slavism.[1] It proclaimed the need for close cooperation between or an alliance with culturally, linguistically or ethnically related peoples of Inner and Central Asian origin[2] like the Finns, Japanese,[3] Koreans,[4][5] Sami, Samoyeds, Hungarians, Turks, Mongols, Manchus[6] and other smaller ethnic groups as a means of securing and furthering shared interests and countering the threats posed by the policies of the great powers of Europe. The idea of a "Turanian brotherhood and collaboration" was borrowed from the pan-Slavic concept of "Slavic brotherhood and collaboration".[7]

The term itself originates from the name of a geographical area, the Turan Depression. The term Turan was widely used in scientific literature from the 18th century onwards to denote Central Asia. European scholars borrowed the term from the historical works of Abu al-Ghazi Bahadur; the annotated English translation of his Shajare-i Türk was published in 1729 and quickly became an oft used source for European scholars.

This political ideology originated in the work of the Finnish nationalist and linguist Matthias Alexander Castrén, who championed the ideology of pan-Turanism—the belief in the racial unity and the future greatness of the Ural-Altaic peoples. He concluded that the Finns originated in Central Asia (more specifically in the Altai Mountains) and far from being a small isolated people, they were part of a larger polity that included such peoples as the Magyars, Turks, Mongols and the like.[8] It implies not only the unity of all Turkic peoples (as in pan-Turkism), but also the alliance of a wider Turanian or Ural-Altaic family believed to include all peoples speaking "Turanian languages".

Although Turanism is a political movement for the union of all Uralo-Altaic peoples, there are different opinions about inclusiveness.[9] In the opinion of the famous Turanist Ziya Gökalp, Turanism is for Turkic peoples only as the other Turanian peoples (Finns, Hungarians, Mongolians and so on) are too different culturally, thus he narrowed Turanism into pan-Turkism.[10] According to the description given by Lothrop Stoddard at the time of World War I:

Right across northern Europe and Asia, from the Baltic to the Pacific and from the Mediterranean to the Arctic Ocean, there stretches a vast band of peoples to whom ethnologists have assigned the name of "Uralo-Altaic race", but who are more generally termed "Turanians". This group embraces the most widely scattered folk—the Ottoman Turks of Constantinople and Anatolia, the Turcomans of Central Asia and Persia, the Tatars of South Russia and Transcaucasia, the Magyars of Hungary, the Finns of Finland and the Baltic provinces, the aboriginal tribes of Siberia and even the distant Mongols and Manchus. Diverse though they are in culture, tradition, and even physical appearance, these peoples nevertheless possess certain well-marked traits in common. Their languages are all similar, and, what is of even more import, their physical and mental make-up displays undoubted affinities.[11]

Origins of pan-Turanianism

The concept of a Ural-Altaic ethnic and language family goes back to the linguistic theories of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz; in his opinion there was no better method for specifying the relationship and origin of the various peoples of the Earth, than the comparison of their languages. In his Brevis designatio meditationum de originibus gentium ductis potissimum ex indicio linguarum,[12] written in 1710, he originates every human language from one common ancestor language. Over time, this ancestor language split into two families: the Japhetic and the Aramaic. The Japhetic family split even further, into Scythian and Celtic branches. The members of the Scythian family were: the Greek language, the family of Sarmato-Slavic languages (Russian, Polish, Czech, Dalmatian, Bulgar, Slovene, Avar and Khazar), the family of Turkic languages (Turkish, Cuman, Kalmyk and Mongolian), the family of Finnic languages (Finnish, Saami, Hungarian, Estonian, Liv and Samoyed). Although his theory and grouping were far from perfect, it had a tremendous effect on the development of linguistic research, especially in German speaking countries.

Pan-Turanianism has its roots in the Finnish nationalist Fennophile and Fennoman movement, and in the works of linguist Matthias Alexander Castrén. The concept spread from here to the kindred peoples of the Finns.

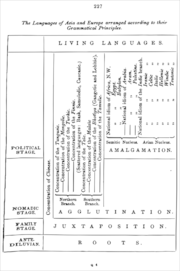

Friedrich Max Müller, the German Orientalist and philologist, published and proposed a new grouping of the non-Aryan and non-Semitic Asian languages in 1855. In his work The Languages of the Seat of War in the East, he called these languages "Turanian". Müller divided this group into two subgroups, the Southern Division, and the Northern Division.[13] In the long run, his evolutionist theory about languages' structural development, tying growing grammatical refinement to socio-economic development, and grouping languages into 'antediluvian', 'familial', 'nomadic', and 'political' developmental stages,[14] proved unsound, but his Northern Division was renamed and re-classed as the Ural-Altaic languages. Nonetheless, his terminology stuck, and the terms 'Turanian peoples' and 'Turanian languages' became parts of common parlance.

Like the term Aryan is used for Indo-European, Turanian is used chiefly as a linguistic term, synonymous with Ural-Altaic.[15]

Both Ural-Altaic and Altaic remain relevant—and still insufficiently understood—concepts of areal linguistics and typology even if in a genetic sense these terms might be considered as obsolete.[16]

Notable countries

Finland

Pan-Turanianism has its roots in the Finnish nationalist Fennophile and Fennoman movement, and in the works of Finnish nationalist and linguist Matthias Alexander Castrén. Castrén conducted more than seven years of fieldwork in western and southern Siberia between 1841 and 1849. His extensive field materials focus on Ob-Ugric, Samoyedic, Ketic, and Turkic languages. He collected valuable ethnographic information, especially on shamanism. Based on his research, he claimed that the Finnic, Ugric, Samoyed, Turkic, Mongolian and Tungusic languages were all of the same 'Altaic family'. He concluded that the Finns originated in Central Asia (in the Altai Mountains), and far from being a small, isolated people, they were part of a larger polity that included such peoples as the Magyars, Turks, Mongols, and so on. Based on his researches, he championed the ideology of pan-Turanism, the belief in the racial unity and the future greatness of the Ural-Altaic peoples. The concept spread from here to the kindred peoples of the Finns. As Castrén put it:

I am determined to show the Finnish nation that we are not a solitary people from the bog, living in isolation from the world and from universal history, but are in fact related to at least one-sixth of mankind. Writing grammars is not my main goal, but without the grammars that goal cannot be attained.[17]

Castrén was of the opinion that Russia was seeking systematically to prevent all development towards freer conditions in Finland, and concluded from this that the Finns must begin to prepare a revolt against Russia. According to him, it was to be linked with a favourable international crisis and would be realised as a general revolt against Russian rule, in which the non-Russian peoples from the Turks and Tatars to the Finns would take part. This political vision of his was shared by some other intellectuals.[18] Fennomans like Elias Lönnrot and Zachris Topelius shared this or an even bolder vision of coming greatness. As Topelius put it:

Two hundred years ago few would have believed that the Slavic tribe would attain the prominent (and constantly growing) position it enjoys nowadays in the history of culture. What if one day the Finnish tribe, which occupies a territory almost as vast, were to play a greater role on the world scene than one could expect nowadays? [...] Today people speak of Pan-Slavism; one day they may talk of Pan-Fennicism, or Pan-Suomism. Within such a Pan-Finnic community, the Finnish nation should hold the leading position because of its cultural seniority [...].[17]

Hungary

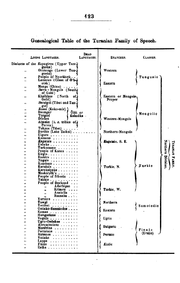

Hungarian Turanism (Hungarian: Turanizmus) was a Romantic nationalist cultural and political movement which was most active from the second half of the 19th century through the first half of the 20th century.[1] It was based on the age old and still living national tradition about the Asian origins of the Magyars. This tradition was preserved in medieval chronicles (such as Gesta Hungarorum[19] and Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum,[20] and the Chronicon Pictum) as early as the 13th century. This tradition served as the starting point for the scientific research about the ethnogenesis of the Hungarian people, which began in the 18th century, both in Hungary and abroad. Sándor Kőrösi Csoma (the writer of the first Tibetan-English dictionary) traveled to Asia in the strong belief that he could find the kindred of the Magyars in Turkestan, amongst the Uyghurs.[21] As a scientific movement, Turanism was concerned with the research about Asia and its culture in the context of Hungarian history and culture. Political Turanism was born in the 19th century, in response to the growing influence of Pan-Germanism and Pan-Slavism, which were seen by Hungarians as very dangerous to the state and nation of Hungary because the country had large ethnic German and Slavic populations.[1] Political Turanism was a romantic nationalist movement, which accentuated the importance of the common ancestry and the cultural affinity of the Hungarians with the peoples of the Caucasus, Inner and Central Asia, like the Turks, Mongols, Parsi and the like, and called for closer collaboration and political alliance with them, as a means to secure and further shared interests, and counter the imminent threats posed by the policies of Western powers like Germany, the British Empire, France and Russia.

The idea of a Hungarian Oriental Institute originated with Jenő Zichy.[22] This idea did not come true. Instead, a kind of lyceum was formed in 1910, called Turáni Társaság (Hungarian Turan Society, also called Hungarian Asiatic Society). The Turan society concentrated on Turan as geographic location where the ancestors of Hungarians might have lived.

The movement received impetus after Hungary's defeat in World War I. Under the terms of the Treaty of Trianon (1920), the new Hungarian state constituted only 32.7% of the territory of historic, pre-treaty Hungary, and it lost 58.4% of its total population. More than 3.2 million ethnic Hungarians (one-third of all Hungarians) resided outside the new boundaries of Hungary in the successor states under oppressive conditions.[23] Old Hungarian cities of great cultural importance like Pozsony (a former capital of the country), Kassa, and Kolozsvár (present-day Bratislava, Košice, and Cluj-Napoca respectively) were lost. Under these circumstances, no Hungarian government could survive without seeking justice for both the Magyars and Hungary. Reuniting the Magyars became a crucial point in public life and on the political agenda. Outrage led many to reject Europe and turn towards the East in search of new friends and allies in a bid to revise the unjust terms of the treaty and restore the integrity of Hungary.

Disappointment towards Europe caused by 'the betrayal of the West in Trianon', and the pessimistic feeling of loneliness, led different strata in society towards Turanism. They tried to look for friends, kindred peoples and allies in the East so that Hungary could break out of its isolation and regain its well deserved position among the nations. A more radical group of conservative, rightist people, sometimes even with an anti-Semitic hint propagated sharply anti-Western views and the superiority of Eastern culture, the necessity of a pro-Eastern policy, and development of the awareness of Turanic racialism among Hungarian people.[24]

The Magyar-Nippon Társaság (Hungarian Nippon Society) was founded by private persons on 1 June 1924 in order to strengthen Hungarian-Japanese cultural relations and exchanges.[25]

Turanism was never embraced officially because it was not in accord with the Christian conservatist ideological background of the regime, but it was used by the government as an informal tool to break the country's international isolation, and build alliances. Hungary signed treaties of friendship and collaboration with the Republic of Turkey in 1923,[26] with the Republic of Estonia in 1937,[27] with the Republic of Finland in 1937,[28] with Japan in 1938,[29] and with Bulgaria in 1941.[30]

After World War II, the Soviet Red Army occupied Hungary. The Hungarian government was placed under the direct control of the administration of the occupying forces. All Turanist organisations were disbanded by the government, and the majority of Turanist publications was banned and confiscated. In 1948, Hungary was converted into a communist one-party state. Turanism was portrayed and vilified as an exclusively fascist ideology although Turanism's role in the interwar development of far-right ideologies was negligible.[31] The official prohibition lasted until the collapse of the socialist regime in 1989.

Turkey

Traditional history cites its early origins amongst Ottoman officers and intelligentsia studying and residing in 1870s Imperial Germany. The fact that many Ottoman Turkish officials were becoming aware of their sense of "Turkishness" is beyond doubt of course, and the role of subsequent nationalists, such as Ziya Gökalp is fully established historically. As the Turkish historian Hasan Bülent Paksoy put it, an aspiration emerged that the Turkic peoples might "form a political entity stretching from the Altai Mountains in Eastern Asia to the Bosphorus".[32] During the late 19th century, the works of renowned Hungarian Orientalist and linguist Ármin Vámbéry contributed to the spreading of Turkish nationalism and Turanism. Vámbéry was employed by the British Foreign office as an advisor and agent. He was paid well for his accounts about his meetings with members of the Ottoman elite and Sultan Abdul Hamid II, and for his essays concerning Ottoman politics.[33] The Ottoman Empire fell into ever deepening decline during the 19th century. There were reform and modernization attempts as early as the 1830s (Tanzimat), but the country was lowered to an almost semi-colonial state at the turn of the century (the state accumulated an enormous amount of debt and state finances were placed under direct foreign control), and the great powers freely preyed on her, occupying or annexing parts of her territory at will (e.g. Cyprus). At the time, the Russian and British empires were antagonists in the so-called "Great Game" to cultivate influence in Persia and Central Asia (Turkestan). Russia and Britain systematically fanned the rivalling nationalisms of the multi-ethnic empire for their own ends,[34][35] and this led to the strengthening of Turkish nationalism as a result. The nationalist movement of the Young Turks aimed for a secularized nation-state, and constitutional government in a parliamentary democracy.

The political party of the Young Turks, the Committee of Union and Progress, embraced Turanism, and a glorification of Turkish ethnic identity, and was devoted to protecting the Turkic peoples living under foreign rule (most of them under Russian rule as a result of Russia's enormous territorial expansion during the 18th and 19th centuries), and to restoring the Ottoman Empire's shattered national pride.[36]

The Turkish version of pan-Turanianism was summed up by American politicians at the time of First World War as follows: "It has been shown above that the Turkish version of pan-Turanianism contains two general ideas: (a) To purify and strengthen the Turkish nationality within the Ottoman Empire, and (b) to link up the Ottoman Turks with the other Turks in the world. These objects were first pursued in the cultural sphere by a private group of 'Intellectuals', and promoted by peaceful propaganda. After 1913, they took on a political form and were incorporated in the programme of the C.U.P.",[37] but Ottoman defeat in World War I briefly undermined the notion of pan-Turanianism.[38]

After World War I, Turkish nationalists and Turanists joined the Basmachi movement of Turkic peoples, to help their struggle against Russians. The most prominent amongst them was Enver Pasha, the former Ottoman war minister.

Turanism forms an important aspect of the ideology of the modern Turkish Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), whose youth movement is informally known as the Grey Wolves. Grey Wolf (the mother wolf Asena) was the main symbol of the ancient Turkic peoples.

Japan

Japanese Turanism was based upon the same footing as its European counterparts. The Austrian German philologist Johann Anton Boller (1811–1869) was the first who systematically tried to prove the Ural-Altaic affiliation of the Japanese language.[39] The Japanese linguist Fujioka Katsuji (1872–1935) put forward a set of mainly typological characteristics linking Japanese to the Ural-Altaic family.[40] The concept of Japanese as a Ural-Altaic language was quite widely accepted prior to the second world war. At present, Japanese is one of the only major language in the world whose genetic affiliation to other languages or language families has not been adequately proven.

Japanese is now thought to be related to southeast asian languages (Austronesian or Austric languages) by linguists Alexander Vovin and Gerhard Jäger.[41][42]

In the 1920s and 30s Turanism got some backing in Japan, mostly amongst the military elite and intelligentsia. Japanese Turanists claimed that Japanese have an Inner Asian descent, and the progenitors of the Japanese people migrated from Central Asia to conquer the Japanese islands. Kitagawa Shikazō (1886–1943) asserted that the Japanese had descended from the Tungusic branch of the Turanian family, just like the Koreans and Manchus, whose origin had been in north-east China, Manchuria. And, since Japanese, Koreans and Manchus derived from a Tungusic origin, they also had a bond with other Turanian sub-ethnicities like Turks, Mongols, Samoyeds and Finno-Ugrians in terms of blood, language and culture.[3] The first-ever Japanese Turanist organization, the Turanian National Alliance – Tsuran Minzoku Domei (ツラン民族同盟), was established in Tokyo in 1921, by Juichiro Imaoka (1888–1973) and the Hungarian Orientalist and ethnographer Benedek Baráthosi Balogh (1870–1945).[3] Other organisations like the Turanian Society of Japan – Nippon Tsuran Kyoukai (early 1930s) and the Japanese-Hungarian Cultural Association – Nikko Bunka Kyoukai (1938) were founded too. A pro-Finnish activity was carried in Japan in the interwar period by some Japanese nationalists influenced by Turanism. It found theoretical expression in, for example, a book entitled Hann tsuranizumu to keizai burokku (Pan-Turanism and the Economic Bloc), written by an economist. The writer insists that the Japanese should leave the tragically small Japanese islands and resettle to the northern and western parts of the Asian continent, where their forefathers had once dwelt. For this purpose, they had to reconquer these ancestral lands from the Slavs by entering into alliance with the Turanian peoples. The Finns, one of those peoples, were to take a share of this great achievement.[43] Turanian kinship along with an anti-communist stance were seen as justification for Japan’s intervention in the Russian and Chinese Civil War, and for the creation of a Japanese sphere of interest, through the creation of new Japanese vassal states in North-East Asia. After the creation of Manchukuo and Mengjiang, Japan pushed for further expansion in the Mongolian People's Republic, but after the Nomonhan Incident gave up on those plans, and concluded the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact with the Soviet Union in 1941.

After Khalkin Gol, the Japanese turned towards South-East Asia and the Pacific under a pan-Asianist agenda.[44]

Most Turanist organisations were disbanded during the Pacific War by an imperial law promoting the Pan-Asian agenda.

Pseudoscientific theories

Turanism has been characterized by pseudoscientific theories.[45][46] According to these theories, "Turanians" include Bulgarians, Estonians, Mongols, Finns, Turks, and even Japanese people and Koreans, who are alleged to share Ural-Altaic origins.[45] Though universally discredited in serious scholarship, Turanism still has extensive support in certain Turkic-speaking countries. Referred to as Pseudo-Turkologists,[47] these scholars stamp all Eurasian nomads and major civilizations in history as being of Turkic or Turanian origin.[48] In such countries, Turanism has served as a form of national therapy, helping its proponents cope with the failures of the past.[49]

Key personalities

- Ali bey Huseynzade

- Ziya Gökalp

- Hüseyin Nihâl Atsız

- Zeki Velidi Togan

- Yusuf Akçura

- Ismail Gaspirali

- Nejdet Sançar

- Turar Ryskulov

- Matthias Alexander Castrén

- Abulfaz Elchibey

- Enver Paşa

- Ömer Seyfettin

- Mehmet Emin Yurdakul

- Munis Tekinalp

- Sadri Maksudi Arsal

- Rıza Nur

- Mirsäyet Soltanğäliev

- Hikmet Tanyu

- Dündar Taşer

- Alparslan Türkeş

- Ármin Vámbéry

- Alajos Paikert

- Torokul Dzhanuzakov

- Ethem Nejat

See also

- Altaic language

- Division of the Mongol Empire

- Gog and Magog

- Greater Finland

- Great Kurultáj

- Heimosodat

- Hungarian neopaganism

- Huns

- Inner Asia

- Japhetic theory

- Khazar theory

- Sun Language Theory

- Tartary

- Turan Group

- Turco-Mongols

- Turkic migration

References and notes

- "FARKAS Ildikó: A magyar turanizmus török kapcsolatai ("The Turkish connections of Hungarian Turanism")". www.valosagonline.hu [Valóság (2013 I.-IV)]. 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- "A „turáni népek” elnevezés már átment a köztudatba és azt kiváló angol, francia, amerikai, német és más tudósok is állandóan használják a tudományosabb, de hosszabb „ural-altai” elnevezés helyett, amellyel az teljesen egyértelmű. Mi turáni eredetű népek alatt Európában főleg a finneket, az észteket, a magyarokat, a bolgárokat és törököket értjük, Ázsiában pedig főleg az egész, nagyon elterjedt török (turk) népcsaládot, mely jelenleg Kis-Ázsia, a kaukázusi táj, Szibéria, Közép- és Kelet-Ázsia (jakutok) nagy részét foglalja magában, továbbá a mongol és mandzsu-tunguz csoportot, mely előbbihez főleg az északi kínaiak, utóbbiakhoz a japániak is tartoznak." _______ "The 'Turanian peoples' denomination has already became established, and it is frequently used by excellent English, French, American, German and other scholars, in place of the more scientific but longer term 'Ural-Altaic', with which it is completely identical. Under the Turanian peoples of Europe we mainly understand the Finns, the Estonians, the Hungarians, the Bulgarians and Turks, and in Asia the widely dispersed family of Turkic peoples who at present encompass large parts of Asia Minor, the Caucasus, Siberia, Central and East Asia (Yakuts), as well as the Mongol and Manchu-Tungusic groups, into the first of which mainly the northern Chinese belong to, and into the latter the Japanese too." ______ PAIKERT Alajos: A turáni népek világhivatása. In: Turán. Vol.XIX. No. 1-4. 1936. p. 19-22. http://real-j.mtak.hu/10683/1/MTA_Turan_1936.pdf

- LEVENT, Sinan: Common Asianist intellectual history in Turkey and Japan: Turanism. 2015. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280490550_Common_Asianist_intellectual_history_in_Turkey_and_Japan_Turanism#pf10

- AI Hyung Il: The Cultural Comparative Perspective in Torii Ryuzo's "Far East": The Search for Japan's Antiquity in Prehistoric Korea. p. 5. http://congress.aks.ac.kr/korean/files/2_1358749979.pdf

- "Many Japanese scholars expressed the idea of Nissen dōsoron (Theory of common ancestry between Japanese and Koreans), which maintained a common origin as well as inferior and superior positions of Koreans and Japanese. Other Japanese scholars concluded that Korea had been historically dominated by influences from the continent, particularly Manchuria." ALLEN, Chizuko: Ch'oe Namson at the Height of Japanese Imperialism. In: Sungkyun Journal of East Asian Studies. Vol. 5 No. 1. 2005. p. 27-49. http://sjeas.skku.edu/upload/201312/Chizuko%20T.PDF

- "圖地布分族民ンラツ Ethnographical Card of Turanians (Uralo-Atlaians)". www.raremaps.com.

- "Britannica.com".

- EB on Matthias Alexander Castrén. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/98799/Matthias-Alexander-Castren

- "Turancılık – (H. Nihal ATSIZ) - Ulu Türkçü Nihal ATSIZ Otağı - Türkçülük - Turancılık ve Hüseyin Nihal Atsız". www.nihal-atsiz.com.

- Türkçülüğün Esasları pg.25 (Gökalp, Ziya)

- STODDARD, T. Lothrop. "Pan-Turanism". The American Political Science Review. Vol. 11, No. 1. (1917) p.16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/1944138.pdf?acceptTC=true

- LEIBNIZ, Gottfried Wilhelm: Brevis designatio meditationum de originibus gentium ductis potissimum ex indicio linguarum. 1710. https://edoc.bbaw.de/files/956/Leibniz_Brevis.pdf

- MÜLLER, Friedrich Max. The languages of the seat of war in the East. With a survey of the three families of language, Semitic, Arian and Turanian. Williams and Norgate, London, 1855. https://archive.org/details/languagesseatwa00mlgoog

- MÜLLER, Friedrich Max: Letter to Chevalier Bunsen on the classification of the Turanian languages. 1854. https://archive.org/details/cu31924087972182

- M. Antoinette Czaplicka, The Turks of Central Asia in History and at the Present Day, Elibron, 2010, p. 19.

- BROWN, Keith and OGILVIE, Sarah eds.:Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. 2009. p. 722.

- SOMMER, Łukasz: Historical Linguistics Applied: Finno-Ugric Narratives in Finland and Estonia. in: The Hungarian Historical Review. Vol. 3. Issue 2. 2014. http://hunghist.org/images/volumes/Volume3_Issue_2/Lukasz.pdf

- PAASVIRTA, Juhani: Finland and Europe: The Period of Autonomy and the International Crises, 1808-1914 1981. p. 68.

- Anonymus: Gesta Hungarorum. http://mek.oszk.hu/02200/02245/02245.htm

- Kézai Simon mester Magyar krónikája. http://mek.oszk.hu/02200/02249/02249.htm

- Magyar Életrajzi Lexikon. http://mek.oszk.hu/00300/00355/html/index.html

- VINCZE Zoltán: Létay Balázs, a magyar asszirológia legszebb reménye http://www.muvelodes.ro/index.php/Cikk?id=155

- PORTIK Erzsébet-Edit: Erdélyi magyar kisebbségi sorskérdések a két világháború között. In: Iskolakultúra 2012/9. p. 60-66. http://epa.oszk.hu/00000/00011/00168/pdf/EPA00011_Iskolakultura_2012-9_060-066.pdf

- UHALLEY, Stephen and WU, Xiaoxin eds.: China and Christianity. Burdened Past, Hopeful Future. 2001. p. 219.

- FARKAS Ildikó: A Magyar-Nippon Társaság. In: Japanológiai körkép. 2007. http://real.mtak.hu/34745/1/Farkas_Magyar_Nippon_Tarsasag_u.pdf

- 1924. évi XVI. törvénycikk a Török Köztársasággal Konstantinápolyban 1923. évi december hó 18. napján kötött barátsági szerződés becikkelyezéséről. http://www.1000ev.hu/index.php?a=3¶m=7599

- 1938. évi XXIII. törvénycikk a szellemi együttműködés tárgyában Budapesten, 1937. évi október hó 13. napján kelt magyar-észt egyezmény becikkelyezéséről. http://www.1000ev.hu/index.php?a=3¶m=8078

- 1938. évi XXIX. törvénycikk a szellemi együttműködés tárgyában Budapesten, 1937. évi október hó 22. napján kelt magyar-finn egyezmény becikkelyezéséről. http://www.1000ev.hu/index.php?a=3¶m=8084

- 1940. évi I. törvénycikk a Budapesten, 1938. évi november hó 15. napján kelt magyar-japán barátsági és szellemi együttműködési egyezmény becikkelyezéséről. http://www.1000ev.hu/index.php?a=3¶m=8115

- 1941. évi XVI. törvénycikk a szellemi együttműködés tárgyában Szófiában az 1941. évi február hó 18. napján kelt magyar-bolgár egyezmény becikkelyezéséről. http://www.1000ev.hu/index.php?a=3¶m=8169

- "While Turanism was and remained little more than a fringe ideology of the Right, the second orientation of the national socialists, pan-Europaism, had a number of adherents, and was adopted as the platform of several national socialist groups." JANOS, Andrew C.: The Politics of Backwardness in Hungary, 1825-1945. 1982. p.275.

- Paksoy, H.B., ‘Basmachi’: TurkestanNational Liberation Movement 1916-1930s – Modern Encyclopedia of Religions in Russia and the Soviet Union, Florida: Academic International Press, 1991, Vol. 4

- CSIRKÉS Ferenc: Nemzeti tudomány és nemzetközi politika Vámbéry Ármin munkásságában. http://www.matud.iif.hu/2013/08/07.htm

- ERICKSON, Edward J.: Ottomans and Armenians. 2013.

- GORECZKY Tamás: Egy görög-török konfliktus története a 19. századból - az 1896-97-es krétai válság az osztrák-magyar diplomáciai iratok tükrében http://real.mtak.hu/19319/1/17-GoretzkyTamas.pdf

- Caravans to Oblivion: The Armenian Genocide, 1915 (Hardcover) by G. S. Graber

- President (1913–1921 : Wilson). The Inquiry. 1917-12/1918 (1917–1918). Records of the American Commission to Negotiate Peace, 1914 – 1931. Series: Special Reports and Studies, 1917 - 1918. Series: Special Reports and Studies, 1917 – 1918 Record Group 256: Records of the American Commission to Negotiate Peace, 1914 – 1931. p. 7.

- Current History. 11. New York City: New York Times Company. 1920. p. 335.

- BOLLER, Johann Anton: Nachweis, dass das Japanische zum ural-altaischen Stamme gehört. 1857. http://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/fs1/object/display/bsb10572378_00001.html

- SHIBATANI Masayoshi: The languages of Japan. 1990. p.96

- Alexander, Vovin. "Proto-Japanese beyond the accent system". Current Issues in Linguistic Theory: 141–156.

- Jäger, Gerhard (2015-10-13). "Support for linguistic macrofamilies from weighted sequence alignment". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (41): 12752–12757. doi:10.1073/pnas.1500331112. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4611657. PMID 26403857.

- MOMOSE Hiroshi: Japan's Relations with Finland 1919–1944, as Reflected by Japanese Source Materials. http://eprints.lib.hokudai.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/2115/5026/1/KJ00000112960.pdf

- “Many Japanese thinkers expressed themselves in pan-Asian terms, in terms of hegemony in East Asia. Obviously, Japan’s pride in her achievement within a relatively short period of sixty years meant that many Japanese thought of their country as the natural leader of East Asia. And the doctrines of the New Order in East Asia and later the Great East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere — imprecise as they were in many respects — were a natural development of this form of nationalism.” in: LEIFER, Michael ed.: Asian Nationalism. 2002. p. 85.

- Nagy, Zsolt (2017). Great Expectations and Interwar Realities: Hungarian Cultural Diplomacy, 1918-1941. Central European University Press. p. 98. ISBN 9633861942.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "The Flowering of Pseudo-Science In Orbán's Hungary". Hungarian Spectrum. August 13, 2018.

- Frankle, Elanor (1948). Word formation in the Turkic languages. Columbia University Press. p. 2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simonian, Hovann (2007). The Hemshin: History, Society and Identity in the Highlands of Northeast Turkey. Routledge. p. 354. ISBN 0230297323.

Thus, ethnic groups or populations of the past (Huns, Scythians, Sakas, Cimmerians, Parthians, Hittites, Avars and others) who have disappeared long ago, as well as non-Turkic ethnic groups living in present-day Turkey, have come to be labeled Turkish, Proto-Turkish or Turanian

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Sheiko, Konstantin; Brown, Stephen (2014). History as Therapy: Alternative History and Nationalist Imaginings in Russia. ibidem Press. pp. 61–62. ISBN 3838265653.

According to Adzhi, Huns, Alans, Goths, Burgundians, Saxons, Alemans, Angles, Langobards and many of the Russians were ethnic Turks.161 The list of non-Turks is relatively short and seems to comprise only Jews, Chinese, Armenians, Greeks, Persians, and Scandinavians... Mirfatykh Zakiev, a Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Tatar ASSR and professor of philology who has published hundreds of scientific works, argues that proto-Turkish is the starting point of the Indo-European languages. Zakiev and his colleagues claim to have discovered the Tatar roots of the Sumerian, ancient Greek and Icelandic languages and deciphered Etruscan and Minoan writings.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Arnakis, George G. (1960). "Turanism: An Aspect of Turkish Nationalism". Balkan Studies. 1: 19–32.

- Atabaki, Touraj (2000). Azerbaijan: Ethnicity and the Struggle for Power in Iran.

- Farrokh, Kaveh (2005) Pan-Turanianism takes aim at Azerbaijan: A geopolitical agenda.

- Landau, J.M. (1995). Pan-Turkism: From Irredentism to Cooperation. London: Hurst.

- Lewis, B. (1962). The Emergence of Modern Turkey. London: Oxford University Press.

- Lewis, B. (1998). The Multiple identities of the Middle East. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Paksoy, H.B. (1991). ‘Basmachi’: TurkestanNational Liberation Movement 1916-1930s. In Modern Encyclopedia of Religions in Russia and the Soviet Union (Vol 4). Florida: Academic International Press.

- Poulton, H. (1997). Top Hat, Grey Wolf, and Crescent: Turkish Nationalism and the Turkish Republic. London, England: Hurst.

- Richards, G. (1997). ‘Race’, Racism and Psychology: Towards a Reflexive History. Routledge.

- Richards Martin, Macaulay Vincent, Hickey Eileen, Vega Emilce, Sykes Bryan, Guida Valentina, Rengo Chiara, Sellitto Daniele, Cruciani Fulvio, Kivisild Toomas, Villerns Richard, Thomas Mark, Rychkov Serge, Rychkov Oksana, Rychkov Yuri, Golge Mukaddes, Dimitrov Dimitar, Hill Emmeline, Bradley Dan, Romano Valentino, Cail Francesco, Vona Giuseppe, Demaine Andrew, Papiha Surinder, Triantaphyllides Costas, Stefanescu Gheorghe, Hatina Jiri, Belledi Michele, Di Rienzo Anna, Novelletto Andrea, Oppenheim Ariella, Norby Soren, Al-Zaheri Nadia, Santachiara-Benerecetti Silvana, Scozzari Rosaria, Torroni Antonio, & Bandelt Hans Jurgen. (2000). Tracing European founder lineages in the Near Eastern mtDNA pool. American Journal of Human Genetics, 67, p. 1251–1276.

- Said, E. (1979). Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books.

- Searle-White, J. (2001). The Psychology of Nationalism. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Toynbee, A.J. (1917). Report on the Pan-Turanian Movement. London: Intelligence Bureau Department of Information, Admiralty, L/MIL/17/16/23.

- Stoddard, T. Lothrop. “Pan-Turanism”. The American Political Science Review. Vol. 11, No. 1. (1917): 12–23.

- Zenkovsky, Serge A. (1960). Pan-Turkism and Islam in Russia. Cambridge-Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Zeman, Zbynek & Scharlau, Winfried (1965), The merchant of revolution. The life of Alexander Israel Helphand (Parvus). London: Oxford University Press. See especially pages 125–144. ISBN 0-19-211162-0 ISBN 978-0192111623