Gagauzia

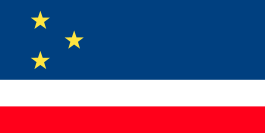

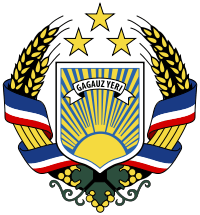

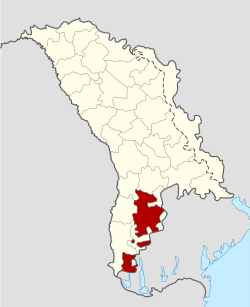

Gagauzia or Gagauz Yeri (Gagauz: Gagauz Yeri or Gagauziya; Romanian: Găgăuzia; Russian: Гагаузия, romanized: Gagauzija), officially the Autonomous Territorial Unit of Gagauzia (Gagauz: Avtonom Territorial Bölümlüü Gagauziya; Romanian: Unitatea Teritorială Autonomă Găgăuzia; Russian: Автономное территориальное образование Гагаузия, romanized: Avtonomnoje territoriaľnoje obrazovanije Gagauzija), is an autonomous region of Moldova. Its autonomy is ethnically motivated by the predominance of the Gagauz people, who are primarily Orthodox Turkic-speaking people.

Autonomous Territorial Unit of Gagauzia | |

|---|---|

Motto: "Long live Gagauzia!" ("Yaşasın Gagauziya!") | |

Autonomous Territorial Unit of Gagauzia

| |

| Capital and largest city | Comrat 46°19′N 28°40′E |

| Official languages | Gagauz, Romanian, Russian |

| Demonym(s) | Gagauz |

| Government | |

• Governor | Irina Vlah (since 15 April 2015) |

| Vladimir Kissa (2017–present) | |

| Legislature | People's Assembly |

| Autonomous region of Moldova | |

• Moldavian SSR founded | 2 August 1940 |

• Gagauz Republic declared | 19 August 1990 |

• Autonomy Agreement reached | 23 December 1994 |

• Autonomy established[1] | 14 January 1995 |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,832 km2 (707 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 0.36 |

| Population | |

| 134,535 | |

• Density | 73.43/km2 (190.2/sq mi) |

| Currency | Moldovan leu (MDL) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| UTC+3 (EEST) | |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +373 |

| Internet TLD | .md |

All of the territory of Gagauzia was part of the Kingdom of Romania in the early 20th century before being carved up into the Soviet Union in 1940 during World War II, incorporating the present day state into the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic. As the Soviet Union began into disintegrate, Gagauzia declared independence in 1990, but was integrated into Moldova in 1994.

Gagauz Yeri literally means "place of the Gagauz".

History

According to some theories, the Gagauz people descend from the Seljuq Turks who settled in Dobruja following the Anatolian Seljuq Sultan Izzeddin Keykavus II (1236–1276). They may be descended from Pechenegs, Uz (Oghuz) and Cuman (Kipchak) peoples.

More specifically, one clan of Oghuz Turks is known to have migrated to the Balkans during intertribal conflicts with other Turks. This Oghuz Turk clan converted from Islam to Orthodox Christianity after settling in medieval Bulgaria, and were called Gagauz Turks. A large group of the Gagauz later left Bulgaria and settled in southern Bessarabia, along with a group of ethnic Bulgarians.

According to other theories, Gagauz are descendants of Kutrigur Bulgarians.[3] In the official Gagauz museum, a plaque mentions that one of the two main theories is that they descend from the Bulgars.

Russian Empire

In 1812, Bessarabia, previously the eastern half of the Principality of Moldavia, was annexed by the Russian Empire following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in the Russo-Turkish War between 1806 and 1812 (see Treaty of Bucharest (1812)). Nogai tribes who inhabited several villages in south Bessarabia (or Budjak) were forced to leave. Between 1812 and 1846, the Russians relocated the Gagauz people from what is today eastern Bulgaria (which was then under the Ottoman Empire) to the orthodox Bessarabia, mainly in the settlements vacated by the Nogai tribes. They settled there together with Bessarabian Bulgarians in Avdarma, Comrat, Congaz, Tomai, Cișmichioi, and other former Nogai villages. Some Gagauz were also settled in the part of the Principality of Moldavia that did not come under Russian control in 1812. But, within several years, villagers moved to live with their own people in the compact area descendants inhabit in the 21st century in the south of Bessarabia.

With the exception of a five-day de facto independence in the winter of 1906, when a peasant uprising declared an autonomous Republic of Comrat, ethnic Gagauzians have been ruled by other dominant groups: the Russian Empire (1812–1917), Romania (1918–1940 and 1941–1944), the Soviet Union (1940–1941 and 1944–1991), and Moldova (1917–1918 and 1991 to date).

Soviet Union

Gagauz nationalism remained an intellectual movement during the 1980s, but strengthened by the end of the decade, as the Soviet Union began to embrace democratic ideals. In 1988, activists from the local intelligentsia aligned with other ethnic minorities to create a movement known as the "Gagauz People". A year later, the "Gagauz People" held its first assembly; they passed a resolution demanding the creation of an autonomous territory in southern Moldova, with the city of Comrat as its capital.

The Gagauzian national movement intensified when Moldavian (Romanian) was accepted as the official language of the Republic of Moldova in August 1989, replacing Russian, the official language of the USSR. A part of the multiethnic population of southern Moldova was concerned about the change in official languages. They had a lack of confidence in the central government in Chișinău. The Gagauz were also worried about the implications for them if Moldova reunited with Romania, as seemed likely at the time. In August 1990, Comrat declared itself an autonomous republic, but the Moldovan government annulled the declaration as unconstitutional. At that time, Stepan Topal emerged as the leader of the Gagauz national movement.

Independent Moldova

Support for the Soviet Union remained high in Gagauzia, with a referendum in March 1991 returning an almost unanimous vote in favour of remaining part of the USSR. Many Gagauz supported the Moscow coup attempt in August 1991, and Gagauzia declared itself an independent republic on 19 August 1991. In September Transnistria declared its independence, thus further straining relations with the government of Moldova. But, when the Moldovan parliament voted on independence on 27 August 1991, six of the 12 Gagauz deputies in the Moldovan parliament voted in favour, while the other six abstained. The Moldovan government began to pay more attention to minority rights.

In February 1994, President Mircea Snegur promised autonomy to the Gagauz, but opposed independence. He was also opposed to the suggestion that Moldova become a federal state made up of three republics: Moldova, Gagauzia, and Transnistria.

In 1994, the Parliament of Moldova awarded to "the people of Gagauzia" (through the adoption of the new Constitution of Moldova) the right of "external self-determination". On 23 December 1994, the Parliament of the Republic of Moldova accepted the "Law on the Special Legal Status of Gagauzia" (Gagauz: Gagauz Yeri), resolving the dispute peacefully. This date is now a Gagauz holiday. Gagauzia is now a "national-territorial autonomous unit" with three official languages: Romanian, Gagauz, and Russian.

Three cities and 23 communes were included in the Autonomous Gagauz Territory: all localities with more than 50% ethnic Gagauz in population, and those localities with between 40% and 50% Gagauz which expressed their desire by referendum to be included to determine Gagauzia's borders. In 1995, Gheorghe Tabunșcic was elected to serve as the Governor (Romanian: Guvernator, Gagauz: Başkan) of Gagauzia for a four-year term, as were the deputies of the local parliament, "The People's Assembly" (Gagauz: "Halk Topluşu"), with Petr Pașalî as chairman.

Dmitrii Croitor won the 1999 governor elections and began to assert the rights granted to the governor by the 1994 agreement. The central authorities of Moldova proved unwilling to accept the results, initiating a lengthy stand-off between the autonomy and Chișinău. Finally Croitor resigned in 2002 due to the pressure from the Moldovan government, which accused him of abuse of authority, relations with the separatist authorities of Transnistria and other charges.

The central electoral commission of Gagauzia did not register Croitor as a candidate for the post of the Governor in the subsequent elections, and Gheorgi Tabunshik was elected in what was described as unfair elections.[4][5] Mihail Formuzal served as the Governor of Gagauzia from 2006 until 2015. That year Irina Vlah was elected to the position, with 51% of the vote.[6]

On 2 February 2014, Gagauzia held a referendum. An overwhelming majority of voters opted for closer ties with Russia over EU integration. They also said they preferred the independence of Gagauzia if Moldova chooses to enter the EU.[7][8]

On 23 March 2015, Irina Vlah was elected as the new governor after a strongly pro-Russian campaign, dominated by the quest for closer ties with the Russian Federation.[9][10]

Geography

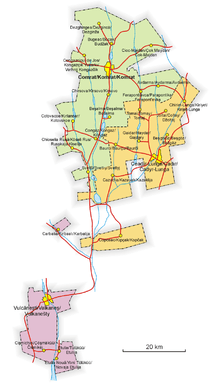

Gagauzia is divided into three districts. It is also split into four enclaves. The main, central enclave includes the cities Comrat and Ceadîr-Lunga and is divided into two districts with those cities serving as administrative centers. The second largest enclave is located around the city of Vulcănești, while two smaller enclaves are the villages of Copceac and Carbalia. The village of Carbalia falls under administration of Vulcănești, while Copceac is part of the Ceadir-Lunga district.

Administrative divisions

Gagauzia consists of one municipality, two cities, and 23 communes containing a total of 32 localities.[11]

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Politics

The autonomy of Gagauzia is guaranteed by the Moldovan constitution and regulated by the 1994 Gagauz Autonomy Act. If Moldova decided to unite with Romania, Gagauzia would have the right of self-determination.[12][13] The Gagauzian People's Assembly (Gagauz: Halk Topluşu; Romanian: Adunarea Populară) has a mandate for lawmaking powers within its own jurisdiction. This includes laws on education, culture, local development, budgetary and taxation issues, social security, and questions of territorial administration. The People's Assembly also has two special powers: it may participate in the formulation of Moldova's internal and foreign policy; and, should central regulations interfere with the jurisdiction of Gagauz-Yeri, it has the right of appeal to Moldova's Constitutional Court.

The highest official of Gagauzia, who heads the executive power structure, is the Governor of Gagauzia (Gagauz: Başkan;Romanian: Guvernatorul Găgăuziei). She/he is elected by popular suffrage for a four-year term, and has power over all public administrative bodies of Gagauzia. She/he is also a member of the Government of the Republic of Moldova. Eligibility for governorship requires fluency in the Gagauz language, Moldovan citizenship, and a minimum age of 35 years.

Permanent executive power in Gagauz Yeri is exercised by the Executive Committee (Bakannik Komiteti/Comitetul Executiv). Its members are appointed by the Governor, or by a simple majority vote in the Assembly at its first session. The Committee ensures the application of the laws of the Republic of Moldova and those of the Assembly of Gagauz-Yeri.

As part of its autonomy, Gagauzia has its own police force.[14]

Gagauz Halkı is a former Gagauz separatist political party, now outlawed.

Elections

Elections for the local governor and parliament as well as referendums take place in the autonomous region.

The population also votes in the national legislatives elections.

| Year | AEI | PCRM |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 23.44% 13,380 | 59.97% 34,224 |

| July 2009 | 11.32% 6,482 | 77.78% 44,549 |

| April 2009 | 2.43% 1,376 | 63.69% 36,094 |

Summary of 28 November 2010 Parliament of Moldova election results in Gagauzia

| Parties and coalitions | Votes | % | +/− | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova | 34,224 | 59.97 | −17.81 | |

| Democratic Party of Moldova | 9,115 | 15.97 | +10.09 | |

| Humanist Party of Moldova | 3,722 | 6.52 | +6.52 | |

| Social Democratic Party | 3,686 | 6.46 | -3.41 | |

| Liberal Democratic Party of Moldova | 3,581 | 6.27 | +4.99 | |

| Other Party | 2,770 | 4.81 | -0.38 | |

| Total (turnout 51.36%) | 57,596 | 100.00 | ||

Economy

The base of the Gagauzian economy is agriculture, particularly viticulture. The main export products are wine, sunflower oil, non-alcoholic beverages, wool, leather and textiles. There are 12 wineries, processing more than 400,000 tonnes annually. There are also two oil factories, two carpet factories, one meat factory, and one non-alcoholic beverage factory.

Transport

There are 451 kilometres (280 mi) of roads in Gagauzia, of which 82% are paved.

Demographics

According to the 2014 census, Gagauzia had a population of 134,132, of which 36.2% urban and 63.8% rural population.

- Births (2010): 2042 (12.7 per 1,000)

- Deaths (2010): 1868 (11.6 per 1,000)

- Growth Rate (2010): 174 (1.1 per 1,000)

Ethnic composition

According to the 2014 census results, the ethnic breakdown in Gagauzia was:[15]

| Ethnic group | Population | Percent of total |

|---|---|---|

| Gagauz | 112,403 | 83.8% |

| Bulgarians | 6,573 | 4.9% |

| Moldovans | 6,304 | 4.7% |

| Russians | 4,292 | 3.2% |

| Ukrainians | 3,353 | 2.5% |

| Others | 1,207 | 0.9% |

There is an ongoing identity controversy over whether Romanians and Moldovans are the same ethnic group. At the census, every citizen could only declare one nationality; consequently, one could not declare oneself both Moldovan and Romanian.

Religion

- Christians – 96.0%

- Orthodox Christians – 93.0%

- Protestant – 3.0%

- Baptists – 1.6%

- Seventh-day Adventists – 0.8%

- Evangelicals – 0.4%

- Pentecostals – 0.2%

- Other – 2.2%

- No Religion – 1.6%

- Atheists – 0.2%

Culture and education

Gagauzia has 55 schools, the Comrat Pedagogical College (high school plus two years over high school), and Comrat State University (Komrat Devlet Universiteti [16]). Turkey financed the creation of a Turkish cultural centre (Türk İşbirliği Ve Kalkınma İdaresi Başkanlığı) and a Turkish library (Atatürk Kütüphanesi). In the village of Beșalma, there is a Gagauz historical and ethnographical museum established by Dimitriy Kara Çöban.

Despite declaring Gagauz as the national language of the Autonomy, the local authorities do not provide any full Gagauz-teaching school, most of those are Russian-language as opposed to inner Moldovan full Romanian language education.[17] Although pupils are introduced to all of the usual school languages (Russian, Romanian, English or French, Gagauz), the local language continues to be the most popular language.[18]

See also

- Gagauz people

- Conflict in Transnistria and Gagauzia

- List of Chairmen of the Gagauzian People's Assembly

References

- "Results of Population and Housing Census in the Republic of Moldova in 2014". National Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Moldova. 2017. Retrieved 2017-05-01.

- Стойков, Руси. Селища и демографски облик в Североизточна България и Южна Добруджа, Известия на Варненското археологическо дружество, т. XV, 1964, с. 98.

- Information on previous elections of Governor of Gagauz ATU Archived 2018-06-20 at the Wayback Machine (in English, Russian, and Romanian))

- Moldova Strategic Conflict Assessment (SCA) Archived 2007-10-25 at the Wayback Machine, Stuart Hensel, Economist Intelligence Unit, Peace Building.

- "Moldova: Semi-Autonomous Region Elects Pro-Russian Leader", The Moscow Times

- Dumitru Minzarari: "The Gagauz Referendum in Moldova: A Russian Political Weapon?", in: Eurasia Daily Monitor, Volume: 11, Issue: 23.

- "Gagauzia Voters Reject Closer EU Ties For Moldova", RFE/RL, February 03, 2014.

- Elia, Danilo (27 March 2015). "E la Găgăuzia vota per Mosca". Osservatorio Balcani Caucaso (in Italian). Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- "Independent candidate Irina Vlakh elected head of Gagauzia". TASS – Russian News Agency. 23 March 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- (in Romanian) Organic Law No. 292-XIV (see Annex 4) Archived 2007-09-26 at the Wayback Machine, Republic of Moldova, 19 February 1999.

- East – West Working Group. Levente Benkö. Autonomy in Gagauzia: A Precedent for Central and Eastern Europe?

- "Opinion on the Law on Modification and Addition in the Constitution of the Republic of Moldova in Particular Concerning the Status of Gagauzia". Council of Europe. 2002. Archived from the original on 2007-12-11. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

- (in Romanian) Moldovan law on the special legal status of Gagauzia

- 2004 census results

- Comrat, street. Galațan, 17,

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-14. Retrieved 2010-03-27.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.gagauzi.ru/2009-09-22-17-54-41/65-panorama/75-2009-09-23-00-50-30%5B%5D

Further reading

- Shabashov A.V., 2002, Odessa, Astroprint, "Gagauzes: terms of kinship system and origin of the people", (Шабашов А.В., "Гагаузы: система терминов родства и происхождение народа")

- Chinn, Jeff; Steven D. Roper (March 1998). "Territorial autonomy in Gagauzia". Nationalities Papers. 26 (1): 87–101. doi:10.1080/00905999808408552.

- Delinski, Andrian; Kahl, Thede; Lozovanu, Dorin; Prishchepov, Aleksandr (ed.) 2014: Gagauziya (Gaguz Yeri). Avtonom Bölgesi Atlası. Atlas of ATU Gagauzia (Gagauz yeri). Chișinău: Proart. ISBN 9789975411653