Meskhetian Turks

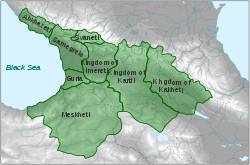

Meskhetian Turks (Turkish: Ahıska Türkleri,[10][11] Georgian: მესხეთის თურქები Meskhetis t'urk'ebi) are an ethnic subgroup of Turks formerly inhabiting the Meskheti region of Georgia, along the border with Turkey. The Turkish presence in Meskheti began with the Turkish military expedition of 1578,[12] although Turkic tribes had settled in the region as early as the eleventh and twelfth centuries.[12]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| est. 400,000 to 600,000[1][2] [3][4][5] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 1,500[6][7] | |

| 150,000-180,000[6][7] | |

| 90,000–110,000[6][7] | |

| 70,000–95,000[7][6] | |

| 42,000-50,000[6][7] | |

| 40,000-76,000[8][6] | |

| 15,000-38,000[8][6] | |

| 8,000-10,000[6][8] | |

| 9,000-16,000[8][6] | |

| 180[6] | |

| Languages | |

| Turkish Azerbaijani · Russian · Georgian · Kazakh | |

| Religion | |

| Islam[9] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Turks and Azerbaijanis (Qarapapaqs and Terekeme) | |

Today, the Meskhetian Turks are widely dispersed throughout the former Soviet Union (as well as in Turkey and the United States) due to forced deportations during World War II. At the time, the Soviet Union was preparing to launch a pressure campaign against Turkey and Joseph Stalin wanted to clear the strategic Turkish population in Meskheti who were likely to be hostile to Soviet intentions.[13] In 1944, the Meskhetian Turks were accused of smuggling, banditry and espionage in collaboration with their kin across the Turkish border. Expelled by Joseph Stalin from Georgia in 1944, they faced discrimination and human rights abuses before and after deportation.[14] Approximately 115,000 Meskhetian Turks were deported to Central Asia and subsequently only a few hundred have been able to return to Georgia. Those who migrated to Ukraine in 1990 settled in shanty towns, inhabited by seasonal workers.[14]

Origins and terms

The origin of the Meskhetian is still unexplored and highly controversial. But now it seems to emerge two main directions:

- The pro-Turkish direction: The Meskhetians were ethnic Turks, descending from Ottoman settlers, in which some Georgian were ethnic parts.[15]

- The pro-Georgian direction: Georgian historiography has traditionally argued that the Meskhetian Turks, who speak the Kars dialect of the Turkish language and belong to the Hanafi school of Sunni Islam, are simply Turkified Meskhetians (an ethnographic subgroup of Georgians) converted to Islam in the period between the sixteenth century and 1829 when the region of Samtskhe-Javakheti (Historical Meskheti) was under the rule of the Ottoman Empire.[16]

However, Anatoly Michailovich Khazanov has argued that "it is quite possible that the adherents of this view oversimplified the ethnic history of the group, particularly if one compares it with another Muslim Georgian group, the Adzhar, who in spite of their conversion to Islam have retained, not only the Georgian language, but to some extent also the Georgian tradition culture and self-identification. Contrary to this, the traditional culture of Meskhetian Turks, though it contained some Georgian elements, was similar to the Turkish one".[16] Kathryn Tomlinson has argued that in Soviet documents about the 1944 deportations of the Meskhetian Turks they were referred to simply as "Turks", and that it was after their second deportation from Uzbekistan that the term "Meskhetian Turks" was invented.[17] Furthermore, according to Ronald Wixman, the term "Meskhetian" only came into use in the late 1950s.[18] Indeed, majority of the Meskhetians call themselves simply as "Turks" or "Ahiskan Turks (Ahıska Türkleri)" referring to the region, meaning "Turks of Ahiska Region". The Meskhetians claim sometimes that the medieval Cumans-Kipchaks of Georgia (Kipchaks in Georgia) may have been one of their possible ancestors.[19]

History

Ottoman conquest

By the Peace of Amasya (1555), Meskheti was divided into two, with the Safavids keeping the eastern part and the Ottomans gaining the western part.[20] In 1578, the Ottomans attacked the Safavid possessions in Georgia, which initiated the Ottoman-Safavid War of 1578-1590, and by 1582 the Ottomans were in possession of the eastern (Safavid) part of Meskheti.[21] The Safavids regained control over the eastern part of Meskheti in the early 17th century.[21] However, by the Treaty of Zuhab (1639), all of Meskheti fell under Ottoman control, and it brought an end to Iranian attempts to retake the region.[22][21]

Soviet rule

1944 deportation from Georgia to Central Asia

On 15 November 1944, the then General Secretary of CPSU, Joseph Stalin, ordered the deportation of over 115,000 Meskhetian Turks from their homeland,[23] who were secretly driven from their homes and herded onto rail cars.[24] As many as 30,000 to 50,000 deportees died of hunger, thirst and cold and as a direct result of the deportations and the deprivations suffered in exile.[25][24] The Soviet guards dumped the Meskhetian Turks at rail sidings across a vast region, often without food, water, or shelter.

According to the 1989 Soviet Census, 106,000 Meskhetian Turks lived in Uzbekistan, 50,000 in Kazakhstan, and 21,000 in Kyrgyzstan.[23] As opposed to the other nationalities who had been deported during World War II, no reason was given for the deportation of the Meskhetian Turks, which remained secret until 1968.[13] It was only in 1968 that the Soviet government finally recognised that the Meskhetian Turks had been deported. The reason for the deportation of the Meskhetian Turks was because in 1944 the Soviet Union was preparing to launch a pressure campaign against Turkey.[13] In June 1945 Vyacheslav Molotov, who was then Minister of Foreign Affairs, presented a demand to the Turkish Ambassador in Moscow for the surrender of three Anatolia provinces (Kars, Ardahan and Artvin).[13] As Moscow was also preparing to support Armenian claims to several other Anatolian provinces, war against Turkey seemed possible, and Joseph Stalin wanted to clear the strategic Georgian-Turkish border where the Meskhetian Turks were settled and who were likely to be hostile to such Soviet intentions.[13]

Unlike the other deported Muslim groups, the Meskhetians have not been rehabilitated nor permitted to return to their homeland. In April 1970, the leaders of the Meskhetian Turkish national movement applied to the Turkish Embassy in Moscow for permission to emigrate to Turkey as Turkish citizens if the Soviet government persisted its refusal to allow them to resettle in Meskheti. However, the response of the Soviet government was to arrest the Meskhetian leaders.[26]

1989 deportation from Uzbekistan to other Soviet countries

In 1989, riots broke out between the Meskhetian Turks who had settled in Uzbekistan and the native Uzbeks.[23] Nationalist resentments against the Meskhetians who had competed with Uzbeks for resources in the overpopulated Fergana valley boiled over. Hundreds of Meskhetian Turks were killed or injured, nearly 1,000 properties were destroyed and thousands of Meskhetian Turks fled into exile.[23] The majority of Meskhetian Turks, about 70,000, went to Azerbaijan, whilst the remainder went to various regions of Russia (especially Krasnodar Krai), Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan[23][27] and Ukraine.

War in Donbass

Around 2,000 Meskhetian Turks have been forced to flee from their homes in Ukraine since May 2014 amid fighting between government forces and pro-Russian separatists. Meskhetian Turkish community representative in the eastern city of Donetsk, Nebican Basatov, said that those who have fled have sought refuge in Russia, Azerbaijan, Turkey and different parts of Ukraine.[14] Over 300 Meskhetian Turks from the Turkish-speaking minority in eastern Ukraine have arrived in eastern Turkey’s Erzincan province where they will live under the country's recently adopted asylum measures.[28]

Demographics

.jpg)

According to the 1989 Soviet Census, there were 207,502 Turks living in the Soviet Union.[1] However, Soviet authorities recorded many Meskhetian Turks as belonging to other nationalities such as "Azeri", "Kazakh", "Kyrgyz", and "Uzbek".[1] Hence, official censuses do not necessarily show a true reflection of the real population of the Meskhetian Turks; for example, according to the 2009 Azerbaijani census, there were 38,000 Turks living in the country; however, no distinction is made in the census between Meskhetian Turks and Turks from Turkey who have become Azerbaijani citizens, as both groups are classified in the official census as "Turks" or "Azerbaijani".[29] According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees report published in 1999, that 100,000 Meskhetian Turks lived in Azerbaijan and the defunct Baku Institute of Peace and Democracy stated, in 2001, that between 90,000 and 110,000 Meskhetian Turks lived in Azerbaijan,[30][31] similarly, academic estimates have also suggested that the Meskhetian Turkish community of Azerbaijan numbers 90,000 to 110,000.[30]

More recently, some Meskhetian Turks in Russia, especially those in Krasnodar, have faced hostility from the local population. The Krasnodar Meskhetian Turks have suffered significant human rights violations, including the deprivation of their citizenship. They are deprived of civil, political and social rights and are prohibited from owning property and employment.[32] Thus, since 2004, many Turks have left the Krasnodar region for the United States as refugees. A large number of them, comprising nearly 1300 individuals, is in Dayton, Ohio. They are still barred from full repatriation to Georgia.[33] However, in Georgia, racism against Meskheti Turks is still in popularity, due to difference in beliefs and ethnic tensions.[34]

Culture

Language

The Meskhetian Turks speak an Eastern Anatolian dialect of Turkish, which hails from the regions of Kars, Ardahan, and Artvin.[36] The Meskhetian Turkish dialect has also borrowed from other languages (including Azerbaijani, Georgian, Kazakh, Kyrgyz, Russian, and Uzbek) which the Meskhetian Turks have been in contact with during the Russian and Soviet rule.[36]

Wedding

Meskhetian Turks' weddings consist of a traditional proposal from the groom’s parents and if the bride’s parents accept the proposal, an engagement party, or Nişan, is done. Everyone at the Nişan is given a ceremonial sweet drink, called Sharbat. The actual wedding lasts for two days. On the first day the bride leaves her house and on the second day is when the marriage happens. Before the bride enters her husband's house she uses the heel on her shoe to break two plates with her foot and applies honey on the doorway. This tradition serves the purpose of wishing happiness upon the new bride and groom in their marriage. At the end of the wedding, a dance ensues with the men and women dancing separately. Finally, the newlyweds have their last dance which is called the ‘Waltz’ and that completes the wedding.[37]

See also

Notes

- Aydıngün et al. 2006, 1.

- Seferov & Akış 2011, 393.

- Today's Zaman (15 August 2011). "Historic Meskhetian Turk documents destroyed". Today's Zaman. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- Kanbolat, Hasan (7 April 2009). "Return of Meskhetian Turks to Georgia delayed". Today's Zaman. Archived from the original on 25 January 2011. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- Assembly of Turkish American Associations (5 February 2008). "ATAA and ATA-SC Visit Ahiska Turks in Los Angeles". Today's Zaman. Archived from the original on 12 December 2010. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- Al Jazeera (2014). "Ahıska Türklerinin 70 yıllık sürgünü". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2016-07-05.

- Aydıngün et al. 2006, 13.

- Aydıngün et al. 2006, 14.

- Aydıngün et al. 2006, 15.

- page78.

- ahiskalilar.org (turkish)

- Aydıngün et al. 2006, 4.

- Bennigsen & Broxup 1983, 30.

- "Clashes force 2,000 Meskhetian Turks to flee Ukraine - World Bulletin". World Bulletin. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- Helmut Glück: Metzler Lexikon Sprache, 2005, p. 774

- Khazanov 1995, 195.

- Tomlinson 2005, 111.

- Wixman 1984, 134.

- Yunusov, Arif. The Akhiska (Meskhetian Turks): Twice Deported People. "Central Asia and Caucasus" (Lulea, Sweden), 1999 # 1(2), p. 162-165.

- Mikaberidze 2015, p. xxxi.

- Floor 2001, p. 85.

- Tomlinson 2005, 110.

- UNHCR 1999b, 20.

- Minahan 2002, 1240.

- Polian 2004, 155.

- Bennigsen & Broxup 1983, 31.

- UNHCR 1999b, 21.

- "Turkey welcomes Meskhetian Turks from east Ukraine - World Bulletin". World Bulletin. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- The State Statistical Committee of the Republic of Azerbaijan. "Population by ethnic groups". Archived from the original on 2012-11-30. Retrieved 2012-01-16.

- UNHCR 1999a, 14.

- NATO Parliamentary Assembly. "Minorities in the South Caucasus: Factor of Instability?". Archived from the original on 2012-03-08. Retrieved 2012-01-16.

- Barton, Heffernan & Armstrong 2002, 9.

- Coşkun 2009, 5.

- "Meskhetian Turks - Minority Rights Group". Minority Rights Group. Retrieved 2017-07-25.

- An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires.

- Aydıngün et al. 2006, 23.

- Ranard, Donald, ed. (2006). Meskhetian Turks: An Introduction to their History, Culture and Resettlement Experiences. Washington, DC: the Center for Applied Linguistics. pp. 18–19.

Bibliography

- Aydıngün, Ayşegül; Harding, Çiğdem Balım; Hoover, Matthew; Kuznetsov, Igor; Swerdlow, Steve (2006), Meskhetian Turks: An Introduction to their History, Culture, and Resettelment Experiences (PDF), Cultural Orientation Resource (COR) Center

- Barton, Frederick D.; Heffernan, John; Armstrong, Andrea (2002), Being Recognised as Citizens (PDF), http://www.humansecurity-chs.org/: Commission on Human Security, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-17

- Bennigsen, Alexandre; Broxup, Marie (1983), The Islamic threat to the Soviet State, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-7099-0619-6.

- Blacklock, Denika (2005), Finding Durable Solutions for the Meskhetians (PDF), European Centre for Minority Issues, archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-02

- Coşkun, Ufuk (2009), Ahiska/Meskhetian Turks in Tucson: An Examination of Ethnic Identity (PDF), University of Arizona, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-11

- Cornell, Svante E. (2001), Small Nations and Great Powers: A Study of Ethnopolitical Conflict in the Caucasus, Routledge, ISBN 0-7007-1162-7.

- Council of Europe (2006), Documents: working papers, 2005 ordinary session (second part), 25–29 April 2005, Vol. 3: Documents 10407, 10449-10533, Council of Europe, ISBN 92-871-5754-5.

- Drobizheva, Leokadia; Gottemoeller, Rose; Kelleher, Catherine McArdle (1998), Ethnic Conflict in the Post-Soviet World: Case Studies and Analysis, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 1-56324-741-0.

- Elbaqidze, Marina (2005), "Multiculturalism in Georgia: Unclaimed Asset or Threat to the State?", in Czyzewski, Krzystof; Kulas, Joanna; Golubiewski, Mikolaj (eds.), A Handbook of Dialogue: Trust and Identity.

- Enwall, Joakim (2010), "Turkish texts in Georgian script: Sociolinguistic and ethno-linguistic aspects", in Boeschoten, Hendrik; Rentzsch, Julian (eds.), Turcology in Mainz, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3-447-06113-8.

- Floor, Willem (2001). Safavid Government Institutions. Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers. ISBN 978-1568591353.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Khazanov, Anatoly Michailovich (1995), "People with Nowhere To Go: The Plight of the Meskhetian Turks", After the USSR: Ethnicity, Nationalism and Politics in the Commonwealth of Independent States, University of Wisconsin Press, ISBN 0-299-14894-7.

- Kurbanov, Rafik Osman-Ogly; Kurbanov, Erjan Rafik-Ogly (1995), "Religion and Politics in the Caucasus", in Bourdeaux, Michael (ed.), The Politics of Religion in Russia and the New States of Eurasia, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 1-56324-357-1.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2015). Historical Dictionary of Georgia (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1442241466.

- Minahan, James (2002), Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: L-R, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-313-32111-6.

- Pepinov, Fuad (2008), "The Role of Political Caricature in the ultural Development of the Meskhetian (Ahiska) Turks", in Kellner-Heinkele, Barbara; Gierlichs, Joachim; Heuer, Brigitte (eds.), Islamic Art and Architecture in the European Periphery: Crimea, Caucasus, and the Volga-Ural Region, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 3-447-05753-X

- Polian, Pavel (2004), Against Their will: The History and Geography of Forced Migrations in the USSR, Central European University Press, ISBN 963-9241-68-7.

- Rasuly-Paleczek, Gabriele; Katschnig, Julia (2005), Central Asia on Display: Proceedings of the VIIth Conference of the European Society for Central Asian Studies, LIT Verlag Münster, ISBN 3-8258-8309-4.

- Rywkin, Michael (1994), Moscow's Lost Empire, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 1-56324-237-0.

- Seferov, Rehman; Akış, Ayhan (2011), Sovyet Döneminden Günümüze Ahıska Türklerinin Yasadıkları Cografyaya Göçlerle Birlikte Genel Bir Bakıs (PDF), Türkiyat Araştırmaları Dergisi, archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-27, retrieved 2012-03-02

- Tomlinson, Kathryn (2005), "Living Yesterday in Today and Tomorrow: Meskhetian Turks in Southern Russia", in Crossley, James G.; Karner, Christian (eds.), Writing History, Constructing Religion, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 0-7546-5183-5.

- UNHCR (1999a), Background Paper on Refugees and Asylum Seekers from Azerbaijan (PDF), United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

- UNHCR (1999b), Background Paper on Refugees and Asylum Seekers from Georgia (PDF), United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

- Wixman, Ronald (1984), The Peoples of the USSR: An Ethnographic Handbook, M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 0-87332-506-0.

References

- Robert Conquest, The Nation Killers: The Soviet Deportation of Nationalities (London: Macmillan, 1970) (ISBN 0-333-10575-3)

- S. Enders Wimbush and Ronald Wixman, "The Meskhetian Turks: A New Voice in Central Asia," Canadian Slavonic Papers 27, Nos. 2 and 3 (Summer and Fall, 1975): 320-340

- Alexander Nekrich, The Punished Peoples: The Deportation and Fate of Soviet Minorities at the End of the Second World War (New York: W. W. Norton, 1978) (ISBN 0-393-00068-0).

- Emma Kh. Panesh and L. B. Ermolov (Translated by Kevin Tuite). Meskhetians. World Culture Encyclopedia. Accessed on September 1, 2007.