Turks in Algeria

The Turks in Algeria, also commonly referred to as Algerian Turks,[3][4][5][6][7] Algerian-Turkish[8][9] Algero-Turkish[10] and Turkish-Algerians[11] (Arabic: أتراك الجزائر; French: Turcs d'Algérie; Turkish: Cezayir Türkleri[12]) are ethnic Turkish descendants who, alongside the Arabs and Berbers, constitute an admixture to Algeria's population.[13][14][15][16] During Ottoman rule, Turkish settlers began to migrate to the region predominately from Anatolia.[17][18] A significant number of Turks intermarried with the native population, and the male offspring of these marriages were referred to as Kouloughlis (Turkish: kuloğlu) due to their mixed Turkish and central Maghrebi heritage.[19][20] However, in general, intermarriage was discouraged, in order to preserve the "Turkishness" of the community.[21] Consequently, the terms "Turks" and "Kouloughlis" have traditionally been used to distinguish between those of full and partial Turkish ancestry.[22]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 5% of Algeria's population being of Turkish descent (2008 Oxford Business Group estimate)[1] 600,000 - 2,000,000 (2008 Turkish Embassy Report)[2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam (Hanafi school) |

In the late nineteenth century the French colonisers in North Africa classified the populations under their rule as "Arab" and "Berber", despite the fact that these countries had diverse populations, which were also composed of ethnic Turks and Kouloughlis.[23] According to the U.S. Department of State "Algeria's population, [is] a mixture of Arab, Berber, and Turkish in origin";[15] whilst Australia's Department of Foreign Affairs has reported that the demographics of Algeria (as well as that of Tunisia) includes a "strong Turkish admixture".[14]

Thus, today, numerous estimates suggest that Algerians of Turkish descent still represent 5%[1][24] to 25% (including partial Turkish origin)[12][25] of the country's population. Since the Ottoman era, the Turks settled mostly in the coastal regions of Algeria and Turkish descendants continue to live in the big cities today.[1] Moreover, Turkish descended families also continue to practice the Hanafi school of Islam (in contrast to the ethnic Arabs and Berbers who practice the Maliki school)[26] and many retain their Turkish-origin surnames—which mostly express a provenance or ethnic Turkish origin from Anatolia.[27][28] The Turkish minority have formed the Association des Turcs algériens (Association of Algerian Turks) to promote their culture.[27]

History

Ottoman era (1515–1830)

The foundation of Ottoman Algeria was directly linked to the establishment of the Ottoman province (beylerbeylik) of the Maghreb at the beginning of the 16th century.[29] At the time, fearing that their city would fall into Spanish hands, the inhabitants of Algiers called upon Ottoman corsairs for help.[29] Headed by Oruç Reis and his brother Hayreddin Barbarossa, they took over the rule of the city and started to expand their territory into the surrounding areas. Sultan Selim I (r. 1512-20) agreed to assume control of the Maghreb regions ruled by Hayreddin as a province, granting the rank of governor-general (beylerbey) to Hayreddin. In addition, the Sultan sent 2,000 janissaries, accompanied by about 4,000 volunteers to the newly established Ottoman province of the Maghreb, whose capital was to be the city of Algiers.[29] These Turks, mainly from Anatolia, called each other "yoldaş" (a Turkish word meaning "comrade") and called their sons born of unions with local women "Kuloğlu’s", implying that they considered their children's status as that of the Sultan's servants.[29] Likewise, to indicate in the registers that a certain person is an offspring of a Turk and a local woman, the note "ibn al-turki" (or "kuloglu") was added to his name.[30]

The exceptionally high number of Turks greatly affected the character of the city of Algiers, and that of the province at large. In 1587, the province was divided into three different provinces, which were established where the modern states of Algeria, Libya and Tunisia, were to emerge. Each of these provinces was headed by a Pasha sent from Constantinople for a three-year term. The division of the Maghreb launched the process that led eventually to the janissary corps' rule over the province.[31] From the end of the 16th century, Algiers's Ottoman elite chose to emphasize its Turkish identity and nurture its Turkish character to a point at which it became an ideology.[31] By so doing, the Algerian province took a different path from that of its neighboring provinces, where local-Ottoman elites were to emerge. The aim of nurturing the elite's Turkishness was twofold: it limited the number of the privileged group (the ocak) while demonstrating the group's loyalty to the Sultan.[31] By the 18th century there was 50,000 janissaries concentrated in the city of Algiers alone.[31]

The lifestyle, language, religion, and area of origin of the Ottoman elite's members created remarkable differences between the Algerian Ottoman elite and the indigenous population.[32] For example, members of the elite adhered to Hanafi law while the rest of the population subscribed to the Maliki school.[32] Most of the elites originated from non-Arab regions of the Empire. Furthermore, most members of the elite spoke Ottoman Turkish while the local population spoke Algerian Arabic and even differed from the rest of the population in their dress.[32]

Recruiting the military-administrative elite

From its establishment, the military-administrative elite worked to reinvigorate itself by enlisting volunteers from non-Arab regions of the Ottoman Empire, mainly from Anatolia.[30] Hence, local recruiting of Arabs was almost unheard of and during the 18th century a more or less permanent network of recruiting officers was kept in some coastal Anatolian cities and on some of the islands of the Aegean Sea.[33] The recruitment policy was therefore one of the means employed to perpetuate the Turkishness of the Ottoman elite and was practiced until the fall of the province in 1830.[33]

Marriages to local women and the Kuloğlus

During the 18th century, the militia practiced a restrictive policy on marriages between its members and local women. A married soldier would lose his right of residence in one of the city's eight barracks and the daily ration of bread to which he was entitled. He would also lose his right to purchase a variety of products at a preferential price.[33] Nonetheless, the militia's marriage policy made clear distinctions among holders of different ranks: the higher the rank, the more acceptable the marriage of its holder.[21] This policy can be understood as part of the Ottoman elite's effort to perpetuate its Turkishness and to maintain its segregation from the rest of the population.[21] Furthermore, the militia's marriage policy, in part, emerged from fear of an increase in the number of the kuloğlus.[35]

The kuloğlu's refers to the male offspring of members of the Ottoman elite and the local Algerian women.[35] Due to their link to the local Algerian population via his maternal family, the kuloğlus' loyalty to the Ottoman elite was suspected because of the fear that they might develop another loyalty; they were therefore considered a potential danger to the elite.[35] However, the son of a non-local woman, herself an "outsider" in the local population, represented no such danger to the Ottoman elite. Therefore, the Algerian Ottoman elite had a clear policy dictating the perpetuation of its character as a special social group separated from the local population.[35]

Nonetheless, John Douglas Ruedy points out that the kuloğlu's also sought to protect their Turkishness:

"Proud and distinctive appearing, Kouloughlis often pretended to speak only Turkish and insisted on worshipping in Hanafi [i.e. Ottoman-built] mosques with men of their own ethnic background. In times of emergency they were called upon to supplement the forces of the ojaq."[36]

In the neighbouring province of Tunisia, the maintenance of the Turkishness of the ruling group was not insisted upon, and the kuloğlus could reach the highest ranks of government. However, the janissary corps had lost its supremacy first to the Muradid dynasty (Murad Bey's son was appointed bey), and then to the Husainid Dynasty. The Tunisian situation partly explains the continuation of the Algerian janissary corps' recruitment policy and the manifest will to distance the kuloğlus from the real centres of power.[37] Nonetheless, high-ranking kuloğlus were in the service of the ocak, in military and in administrative capacities, occupying posts explicitly considered out of bounds for them; although there were no kuloğlus who was dey during the 18th century, this seems to be the only exception.[38]

French era (1830–1962)

.jpg)

Once Algeria came under French colonial rule in 1830, approximately 10,000 Turks were expelled and shipped off to Smyrna; moreover, many Turks (alongside other natives) fled to other regions of the Ottoman realms, particularly to Palestine, Syria, Arabia, and Egypt.[43] Nonetheless, by 1832, many Algerian-Turkish descended families, who had not left Algeria, joined a coalition with Emir Abdelkader in order to forge the beginning of a powerful resistance movement against French colonial rule.[8]

In 1926 Messali Hadj - an Algerian of Turkish origin - founded the first modern nationalist movement for Algerian independence.[39] Another prominent Algerian nationalist leader of Turkish origin was Ahmed Tewfik El Madani[42] who, as the leader of the Association of Algerian Muslim Ulema, continued to influence Algerian nationalism. Ahmed Tewfik was also a historian who argued that the Turkish era in Algeria was defamed by European historians and provided the French with convincing arguments to justify their colonial actions.[44] He maintained that the Ottoman Turks had unified Algeria's territory and saved the country from the grip of Christianity as well as from the fate of Muslim Spain. Furthermore, he stated that the Turks who settled in Algeria were "perfection and nobility itself" and emphasised their contributions to Algerian society, such as the establishment of religious endowments, mosques and waterworks.[45] By 1956 the Reformist Ulema, under the leadership of Ahmed Tewfik, joined the Algerian National Liberation Front to fight for Algerian independence.[46]

Algerian Republican era (1962–present)

In 2011 Algerian journalist Mustafa Dala reported in the "Echorouk El Yawmi" that Algerians of Turkish origin - particularly the youth - are seeking to revive the Turkish language in Algeria. In his investigation, Dala found that the Turkish minority are already distinguishable by their different customs, especially in regards to clothes and foods, as well as by their Turkish surnames. However, he states that the revival of the Turkish language is a sign of the minority restoring their identity and highlights the "new Ottomans" in Algeria.[47]

Common surnames used by the Turkish minority

.jpg)

By provenance

The following list are examples of Turkish origin surnames which express an ethnic and provenance origin from Eastern Thrace and Anatolia - regions which today form the modern borders of the Republic of Turkey:

| Surname used in Algeria | Turkish | English translation |

|---|---|---|

| Baghlali | Bağlılı | from Bağlı (in Çanakkale)[52] |

| Bayasli | Payaslı | from Payas[53] |

| Benkasdali Benkazdali | Ben Kazdağılı | I am from Kazdağı[54][55] |

| Benmarchali | Ben Maraşlı | I am from Maraş[56] |

| Benterki | Ben Türk | I am Turk/Turkish[57] |

| Bentiurki Benturki | Ben Türk | I am Turk/Turkish[57] |

| Ben Turkia Ben Turkiya | Ben Türkiye | I am [from] Turkey[57] |

| Bersali Borsali Borsari Borsla | Bursalı | from Bursa[57][58] |

| Boubiasli | Payaslı | from Payas[53] |

| Chatli | Çatlı | from Çat (in Erzurum)[59] |

| Chilali | Şileli | from Şileli (in Aydın)[60] |

| Cholli | Çullu | from Çullu (in Aydın)[60] |

| Coulourli | Kuloğlu | Kouloughli (mixed Turkish and Algerian origin)[61] |

| Dengezli Denizli Denzeli | Denizli | from Denizli[51] |

| Dernali | Edirneli | from Edirne[62] |

| Djabali | Cebali | from Cebali (a suburb in Istanbul)[63] |

| Djeghdali | Çağataylı | Chagatai (Turkic language)[64] |

| Djitli | Çitli | from Çit (in Adana or Bursa)[65] |

| Douali | Develi | from Develi (in Kayseri)[62] |

| Guellati | Galatalı | from Galata (in Istanbul)[64] |

| Kamen | Kaman | Kaman (in Nevşehir)[66] |

| Karabaghli | Karabağlı | from Karabağ (in Konya)[66] |

| Karadaniz | Karadeniz | from the Black Sea region[66] |

| Karaman | Karaman | from Karaman[66] |

| Kasdali Kasdarli | Kazdağılı | from Kazdağı[54] |

| Kaya Kayali | Kayalı | from Kaya (applies to the villages in Muğla and Artvin)[54] |

| Kebzili | Gebzeli | from Gebze (in Kocaeli)[54] |

| Keicerli | Kayserili | from Kayseri[55] |

| Kermeli | Kermeli | from the Gulf of Kerme (Gökova)[54] |

| Kezdali | Kazdağılı | from Kazdağı[55] |

| Kissarli Kisserli | Kayserili | from Kayseri[55] |

| Korghlu Korglu Koroghli Korogli | Kuloğlu | Kouloughli (mixed Turkish and Algerian origin)[67] |

| Koudjali Kouddjali | Kocaeli | from Kocaeli[55][61] |

| Koulali | Kulalı | from Kulalı (in Manisa)[61] |

| Kouloughli Koulougli Kouroughli Kouroughlou | Kuloğlu | A Kouloughli (mixed Turkish and Algerian origin)[61] |

| Kozlou | Kozlu | from Kozlu (in Zonguldak)[55] |

| Manamani Manemeni Manemenni | Menemenli | from Menemen (in Izmir)[68] |

| Mansali | Manisalı | from Manisa[68] |

| Meglali | Muğlalı | from Muğla[68] |

| Merchali Mersali | Maraşlı | from Maraş[68] |

| Osmane Othmani | Osman Osmanlı | Ottoman[69] |

| Ould Zemirli Ould Zmirli | İzmirli | from Izmir[70] |

| Rizeli | Rizeli | from Rize[71] |

| Romeili Roumili | Rumeli | from Rumelia[71] |

| Sanderli | Çandarli | from Çandarlı[71] |

| Sandjak Sangaq | Sancak | from [a] sanjak (an administrative unit of the Ottoman Empire)[59] |

| Satli | Çatlı | from Çat (in Erzurum)[59] |

| Sekelli | İskeleli | from Iskele (in Muğla, Seyhan, or the island of Cyprus)[59] |

| Sekli | Sekeli | from Seke (in Aydın)[59] |

| Skoudarli | Üsküdarlı | from Üsküdar (in Istanbul)[60] |

| Stamboul Stambouli | İstanbulu | from Istanbul[72] |

| Tchambaz | Cambaz | Cambaz (in Çanakkale)[73] |

| Takarli | Taraklı | from Taraklı (in Adapazarı)[60] |

| Tchanderli Tchenderli | Çandarlı | from Çandarlı[62][71] |

| Tekali | Tekeeli | from Tekeeli (a coastal area between Alanya and Antalya)[72] |

| Terki Terqui | Türki | Turkish (language)[74] |

| Terkman Terkmani | Türkmenli | Turkmen (from Anatolia/Mesopotamia)[74] |

| Torki | Türk | Turkish[74] |

| Tourki Tourquie Turki | Türk | Turk/Turkish[74] |

| Yarmali | Yarmalı | from Yarma (in Konya)[70] |

| Zemerli Zemirli Zmerli Zmirli | İzmirli | from Izmir[70][75] |

| Zemir Zmir | İzmir | Izmir[75] |

The following list are examples of Turkish origin surnames which express a provenance settlement of Turkish families in regions of Algeria:

| Surname used in Algeria | Turkish | Meaning in English |

|---|---|---|

| Tlemsanili Tilimsani | Tilimsanılı | from Tlemcen[74] |

The following list are examples of Turkish origin surnames traditionally used by Turkish families in Constantine:

Acheuk-Youcef,[76] Ali Khodja,[76] Bachtarzi,[76] Benabdallah Khodja,[76] Benelmadjat,[76] Bestandji,[76] Bendali Braham,[76] Bentchakar,[76] Bensakelbordj,[76] Bentchikou,[76] Khaznadar,[76] Salah Bey,[76] Tchanderli Braham.[76]

By occupation

The following list are examples of some Turkish origin surnames which express the traditional occupation of Turkish families which settled in Algeria:

| Surname used in Algeria | Turkish | English translation |

|---|---|---|

| Agha | ağa | agha[77] |

| Ahtchi | ahçı, aşçı | cook, keeper of restaurant[77] |

| Anberdji | ambarcı | storekeeper[77] |

| Aoulak | ulak | messenger, courier[52] |

| Arbadji | arabacı | driver[77] |

| Atchi | atçı | horse breeder[77] |

| Bacha | paşa | a pasha[49] |

| Bachagha | başağa | head agha[49] |

| Bachchaouch | başçavuş | sergeant major[49] |

| Bachesais | başseyis | head stableman[49] |

| Bachtaftar | başdefterdar | treasurer[49] |

| Bachtarzi | baş terzi | chief tailor[49] |

| Bachtoubdji | baştopçu | chief cannoneer, artilleryman[49] |

| Baldji | balcı | maker or seller of honey[49] |

| Bazarbacha Bazarbarchi | pazarbaşı | head of bazaar[53] |

| Benabadji | ben abacı | [I am a] maker or seller of garments[78] |

| Benchauch | ben çavuş | [I am a] sergeant[56] |

| Benchoubane | ben çoban | [I am a] shepherd[57] |

| Bendamardji | ben demirci | [I am a] metalworker[78][62] |

| Bendali | ben deli | [I am a] deli (Ottoman troops)[78] |

| Benlagha | ben ağa | [I am a] agha[56] |

| Benstaali | ben usta | [I am a] master, workman, craftsman[56] |

| Bentobdji | ben topçu | [I am a] cannoneer[57] |

| Bestandji Bostandji | bostancı | bostandji[58] |

| Bouchakdji | bıçakçı | cutler[73] |

| Boudjakdji | ocakçı | chimney sweep[73] |

| Boyagi | boyacı | painter[58] |

| Chalabi Challabi | çelebi | educated person, gentlemen[73] |

| Chaouche | çavuş | sergeant[59] |

| Chembaz Chembazi | cambaz | acrobat[60] |

| Damardji Damerdji | demirci | metalworker[78][62] |

| Debladji | tavlacı | stable boy or backgammon player[51] |

| Dey | dayı | officer or maternal uncle[51] |

| Djadouadji | kahveci | coffee maker or seller[79] |

| Djaidji | çaycı | tea seller[79] |

| Doumandji | dümenci | helmsman[79] |

| Doumardji | tımarcı | stableman[63] |

| Dumangi | dümenci | helmsman[79] |

| Dumargi | tımarcı | stableman[63] |

| Fenardji | fenerci | lighthouse keeper[63] |

| Fernakdji | fırıncı | baker[63] |

| Hazerchi | hazırcı | seller of ready-made clothing[65] |

| Kahouadji | kahveci | café owner or coffee maker/grower[65] |

| Kalaidji | kalaycı | tinner[66] |

| Kaouadji | kahveci | café owner or coffee maker/grower[65] |

| Kasbadji | kasapcı | butcher[54] |

| Kassab | Kasap | butcher[54] |

| Kaznadji | hazinedar | keeper of a treasury[54] |

| Kebabdji | kebapçı | kebab seller[80] |

| Kehouadji | kahveci | café owner or coffee maker/grower[54] |

| Ketrandji | katrancı | tar seller[55] |

| Khandji | hancı | innkeeper[65] |

| Khaznadar | hazinedar | keeper of a treasury[65] |

| Khaznadji | hazinedar | keeper of a treasury[80] |

| Khedmadji | hizmetçi | maid, helper[80] |

| Khodja Khoudja | hoca | teacher[80] |

| Louldji | lüleci | maker or seller of pipes[68] |

| Koumdadji | komando | commando[61] |

| Moumdji Moumedji | mumcu | candle maker[81] |

| Ouldchakmadji | çakmakçı | maker or seller of flints/ maker or repairer of flintlock guns[81] |

| Nefradji | nüfreci | prepares amulets[81] |

| Pacha | paşa | a pasha[81] |

| Rabadji | arabacı | driver[61] |

| Rais | reis | chief, leader[61] |

| Saboudji Saboundji | sabuncu | maker or seller of soap[71] |

| Selmadji | silmeci | cleaner or to measure[60] |

| Serkadji | sirkeci | maker or seller of vinegar[60] |

| Slahdji | silahçı | gunsmith[60] |

| Staali | usta | master, workman, craftsman[72] |

| Tchambaz | cambaz | acrobat[73] |

Other surnames

| Surname used in Algeria | Turkish | English translation |

|---|---|---|

| Arslan | aslan | a lion[77] |

| Arzouli | arzulu | desirous, ambitious[77] |

| Baba Babali | baba | a father[52] |

| Badji | bacı | elder sister[52] |

| Bektach | bektaş | member of the Bektashi Order[53] |

| Belbey | bey | mister, gentlemen[53] |

| Belbiaz | beyaz | white[53] |

| Benchicha | ben şişe | [I am] a bottle[56] |

| Benhadji | ben hacı | [I am] a Hadji[78] |

| Benkara | ben kara | [I am] dark[56] |

| Bensari | ben sarı | [I am] blonde[56] |

| Bentobal Bentobbal | ben topal | [I am] crippled[57] |

| Bermak | parmak | finger[57] |

| Beiram Biram | bayram | holiday, festival[58] |

| Beyaz | beyaz | white[57] |

| Bougara Boulkara | bu kara | [this is] dark[57][73] |

| Boukendjakdji | kancık | mean[73] |

| Caliqus | çalıkuşu | goldcrest[73] |

| Chalabi Challabi | çelebi | educated person, gentlemen[71] |

| Chelbi | çelebi | educated person, gentlemen[59] |

| Cherouk | çürük | rotten[60] |

| Dali Dalibey Dalisaus | deli | brave, crazy[62] |

| Damir | demir | metal[62] |

| Daouadji | davacı | litigant[62] |

| Deramchi | diremci | currency[51] |

| Djabali | çelebi | educated person, gentlemen[63] |

| Doumaz | duymaz | deaf[63] |

| Eski | eski | old[63] |

| Gaba | kaba | rough, heavy[63] |

| Goutchouk | küçük | small, little[65][67] |

| Gueddjali | gacal | domestic[64] |

| Guendez | gündüz | daytime[64] |

| Guermezli | görmezli | blind[65][67] |

| Guertali | kartal | eagle[65] |

| Hadji | hacı | Hadji[65] |

| Hidouk | haydut | bandit[80] |

| Ioldach | yoldaş | companion, comrade[81][81] |

| Kara | kara | dark[81] |

| Karabadji | kara bacı | dark sister[66] |

| Kardache | kardeş | brother[66] |

| Karkach | karakaş | dark eyebrows[81] |

| Kermaz | görmez | blind[65][67] |

| Kerroudji | kurucu | founder, builder, veteran[55] |

| Kertali | kartal | eagle[55] |

| Koutchouk | küçük | small, little[65][67] |

| Lalali Lalili | laleli | tulip[67] |

| Maldji | malcı | cattle producer[81] |

| Mestandji | mestan | drunk[81] |

| Oldach | yoldaş | companion, comrade[81][81] |

| Oualan | oğlan | boy[70] |

| Ouksel | yüksel | to succeed, achieve[70] |

| Ourak | orak | sickle[70] |

| Salakdji | salakça | silly[71] |

| Salaouatchi Salouatchi | salavatçaı | prayer[71] |

| Sari | sarı | yellow or blond[59] |

| Sarmachek | sarmaşık | vine[59] |

| Sersar Sersoub | serseri | layabout, vagrant[60] |

| Tache | taş | stone, pebble[73] |

| Tarakli | taraklı | having a comb, crested[73] |

| Tchalabi | çelebi | educated person, gentlemen[73] |

| Tchalikouche | çalıkuşu | goldcrest[73] |

| Tenbel | tembel | lazy[74] |

| Tobal Toubal | topal | cripple[74] |

| Yataghan Yataghen | yatağan | yatagan[70] |

| Yazli | yazılı | written[70] |

| Yekkachedji | yakışmak | to suit[75] |

| Yesli | yaslı | mourning[75] |

| Yoldas | yoldaş | companion, comrade[81][81] |

Culture

.jpg)

.jpg)

The Algerian Turks generally take pride in their Ottoman-Turkish heritage but also have integrated successfully into Algerian society. Their identity is based on their ethnic Turkish roots and links to mainland Turkey but also to the customs, language, and local culture of Algeria.[69] Due to the three centuries of Turkish rule in Algeria, today many cultural (particularly in regards to food, religion, and dress - and to a lesser extent language), architectural, as well as musical elements of Algeria are of Turkish origin or influence.[69]

Language

During the Ottoman era, the Ottoman Turkish language was the official governing language in the region, and the Turkish language was spoken mostly by the Algerian Turkish community.[32] However, today most Algerian Turks speak the Arabic language as their mother tongue. Nonetheless, the legacy of the Turkish language is still apparent and has influenced many words and vocabulary in Algeria. An estimated 634 Turkish words are still used in Algeria today.[83] Therefore, in Algerian Arabic it is possible for a single sentence to include an Arabic subject, a French verb, and for the predicate to be in Berber or Turkish.[84]

Moreover, families of Turkish origin have retained their Turkish family surnames; common names include Barbaros, Hayreddin, Osmanî, Stambouli, Torki, Turki, and Uluçali; job titles or functions have also become family names within the Algerian-Turkish community (such as Hazneci, Demirci, Başterzi, Silahtar).[69][85]

Religion

The Ottoman Turks brought the teaching of the Hanafi law of Sunni Islam to Algeria; consequently, their lifestyle created remarkable differences between the Ottoman Turks and the indigenous population because the ethnic Arabs and Berbers practiced the Maliki school.[32][86]

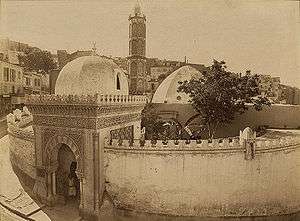

Today, the Hanafi school is still practiced among the Turkish descended families. Moreover, the Ottoman mosques in Algeria - which are still used by the Turkish minority - are distinguishable by their octagonal minarets which were built in accordance with the traditions of the Hanafi rite.[87][88]

Demographics

Population

The Turkish minority is estimated to form between 5%[1][24] to 25%[12][25] of Algeria's total population, the latter including those of partial Turkish origin.

In 1993 the Turkish scholar Prof. Dr. Metin Akar estimated that there was 1 million Turks living in Algeria.[90] By 2008 a country report of Algeria by the Oxford Business Group stated that 5% of Algeria's 34.8 million inhabitants were of Turkish descent (accounting to 1.74 million).[1] In the same year, a report by the Turkish Embassy in Algeria stated that there was between 600,000-700,000 people of Turkish origin living in Algeria; however, the Turkish Embassy report also stated that according to the French Embassy's records there was around 2 million Turks in Algeria.[2]

In recent years, several Turkish academics,[91] as well as Turkish official reports,[92] have reiterated that estimates of the Turkish population range between 600,000 and 2 million. However, a 2010 report published by the Directorate General for Strategy Development points out that these estimates are likely to be low because 1 million Turks migrated and settled in Algeria throughout the 315 years of Ottoman rule. Moreover, the report suggests that due to intermarriages with the local population, 30% of Algeria's population was of Turkish origin in the eighteenth century.[92] In 1953 the Turkish scholar Dr. Sabri Hizmetli claimed that people of Turkish origin still made up 25% of Algeria's population.[25]

By 2013 the American historian Dr. Niki Gamm argued that the total population of Turkish origin remains unclear and that estimates range between 5-10% of Algeria's population of 37 million (accounting to between 1.85 million and 3.7 million)[24] However, by 2015 the Russian government-controlled news agency Sputnik, citing the 2014 Algerian population statistics, reported that there are 760,000 people of full Turkish origin (i.e. 2% of Algeria's population), whilst those of full and partial Turkish origin account to 9.5 million of Algeria's 38 million inhabitants (i.e. 25% of Algeria's population).[12]

Areas of settlement

Since the Ottoman era, urban society in the coastal cities of Algeria evolved into an ethnic mix of Turks and Kouloughlis as well as other ethnic groups (Arabs, Berbers, Moors, and Jews).[94] Thus, the Turks settled mainly in the big cities of Algeria and formed their own Turkish quarters; remnants of these old Turkish quarters are still visible today,[95] such as in Algiers (particularly in the Casbah)[96][97] Annaba,[98] Biskra,[99] Bouïra,[100] Médéa,[101][102] Mostaganem,[102] and Oran (such as in La Moune[97] and the areas near the Hassan Basha Mosque[103]). Indeed, today, the descendants of Ottoman-Turkish settlers continue to live in the big cities.[1] In particular, the Turks have traditionally had a strong presence in the Tlemcen Province; alongside the Moors, they continue to make up a significant portion of Tlemcen's population and live within their own sectors of the city.[104][93]

The Turkish minority have traditionally also had notable populations in various other cities and towns; there is an established Turkish community in Arzew,[105] Bougie,[106] Berrouaghia, Cherchell,[107] Constantine,[106] Djidjelli,[106] Mascara, Mazagran[105] Oued Zitoun,[108] and Tebessa.[106] There is also an established community in Kabylie (such as Tizi Ouzou[109] and Zammora).

Moreover, several suburbs, towns and cities, which have been inhabited by the Turks for centuries, have been named after Ottoman rulers, Turkish families or the Turks in general, including: the Aïn El Turk district (literally "Fountain of the Turks") in Oran, the town of Aïn Torki in the Aïn Defla Province, the Aïn Turk commune in Bouïra, the town of Bir Kasdali and the Bir Kasd Ali District in the Bordj Bou Arréridj Province,[110][54] the town of Bougara and the Bougara District located in Blida Province,[57] the suburb of Hussein Dey and the Hussein Dey District in the Algiers Province, as well as the town of Salah Bey and the Salah Bey District in the Sétif Province.[76]

.jpg)

Diaspora

There are many Algerian Turks who have emigrated to other countries and hence make up part of Algeria's diaspora. Initially, the first wave of migration occurred in 1830 when many Turks were forced to leave the region once the French took control over Algeria; approximately 10,000 were shipped off to Turkey whilst many others migrated to other regions of the Ottoman Empire, including Palestine, Syria, Arabia, and Egypt.[43] Furthermore, some Turkish/Kouloughli families also settled in Morocco (such as in Tangier and Tétouan).[112]

In regards to modern migration, there is a noticeable Algerian community of Turkish descent living in England.[12][113] Many Algerians attend the Suleymaniye Mosque which is owned by the British-Turkish community.[114] There is also thousands of Algerian Turks living in France.[12] Furthermore, some Algerian Turks have also migrated to other European countries;[12] in particular, Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, as well as Canada in North America, are top receiving countries of Algerian citizens.[115]

Organizations and associations

- The Association of Algerian Turks (Association des Turcs algériens)[69]

Notable people

- Patrick Abada, French pole vaulter and Olympian[120]

- Mustapha Adane, painter[121]

- Ghemati Abdelkrim, politician[122]

- Ali Khodja Ali (fr), painter[121]

- Mahieddine Bachtarzi, actor and singer[48]

- Benaouda Hadj Hacène Bachterzi, politician and publicist[123]

- Hacène Benaboura, artist[124]

- Mohamed Bencheneb, writer[125]

- Lakhdar Ben Cherif, poet[128]

- Dr Mohammed Saleh Bendjelloul, politician[129]

- Slimane Bengui, director of the first French-language Algerian newspaper "El Hack"[130]

- Djelloul Benkalfate educator and socialist[131]

- Benyoucef Benkhedda, politician[132]

- Mustapha Benkhemmar, musician

- Larbi Bensari (fr), musician

- Abdelhalim Bensmaia, scholar[133]

- Abdelhalim Ben Smaya, scholar[134]

- Lakhdar Ben-Tobbal, resistance fighter[135]

- Ahmed Ben-Triki ("Ben Zengli"), poet[136]

- Abderrahmane Berrouane, politician[137]

- Ahmed Chaouch, caïd[138]

- Ahmed Bey, the last Bey of Constantine[139]

- Abdelaziz Bouteflika, the President of Algeria[140]

- Leïla Chellabi, writer[141]

- Abdelkrim Dali (fr), musician[142]

- Mustapha Haciane, poet[111]

- Ahmed Ben Messali Hadj, politician[41][143]

- Djanina Messali-Benkelfat, writer[144]

- Salim Halali, singer[116][117]

- Mourad Kaouah, Deputy of Algiers (1958 to 1962), French politician, and football player[145]

- Ahmed Kara-Ahmed (fr), painter

- Hamdan Khodja, scholar and merchant[146]

- Mohamed-Réda Benabdallah Khodja, artist[147]

- Mustapha Khodja (fr), lieutenant of the National Liberation Army

- Dr. Ben Lerbey, possibly the first Algerian doctor[148]

- Ahmed Tewfik El Madani, politician[149]

- Ahmed Magdy, Algerian-Egyptian actor[150]

- Ibn Hamza al-Maghribi, Ottoman mathematician

- Abdelmalek Mohieddine, officer[151]

- Mustapha Nador (fr), musician[152]

- Hasan Pasha (son of Barbarossa), three-times Beylerbey of the Regency of Algiers

- Mohammed Racim, artist[118]

- Omar Racim, artist and writer[118]

- Omar Benmahmoud Ali Raïs, sportsman[153]

- Hadj Sameer, archaeologist and artist[154]

- Kaddour Sator (fr), politician and lawyer[155]

- Leïla Sebbar, writer[50]

- Mohamed Sfinja, musician[156]

- Chérif Sid-Cara, Doctor and French politician[157]

- Nafissa Sid-Cara, French politician[157]

- Mustapha Skandrani, musician[158]

- Benjamin Stambouli, football player

- Henri Stambouli, football player

- Mustapha Stambouli, politician[159]

- Athmane Tartag (fr), General[140]

- Wassyla Tamzali, writer[119]

- Boualem Titiche (fr), musician[160]

- Mohammed Zmirli (fr), painter

- Malek Bennabi (fr), thinker [161]

- Mahboub Bati (fr), songwriter

- Djamel Chanderli (fr), filmmaker

- Benali Boudghène dit Colonel Lotfi (fr), resistance fighter

See also

Notes

^ a: "Kouloughlis" refers to the offspring (or descendants) of Turkish fathers and Algerian mothers.[36]

References

- Oxford Business Group (2008), The Report: Algeria 2008, Oxford Business Group, p. 10, ISBN 978-1-902339-09-2,

...the Algerian population reached 34.8 million in January 2006...Algerians of Turkish descent still represent 5% of the population and live mainly in the big cities [accounting to 1.74 million]

- Turkish Embassy in Algeria (2008), Cezayir Ülke Raporu 2008, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, p. 4, archived from the original on 29 September 2013,

Bunun dışında, büyük bir bölümü Tlemcen şehri civarında bulunan ve Osmanlı döneminde buraya gelip yerleşen 600-700 bin Türk kökenli kişinin yaşadığı bilinmektedir. Fransız Büyükelçiliği, kendi kayıtlarına göre bu rakamın 2 milyon civarında olduğunu açıklamaktadır.

- de Tocqueville, Alexis (2001), "Second Letter on Algeria", Writings on Empire and Slavery, Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 15, ISBN 0801865093

- Garcés, María Antonia (2005), Cervantes in Algiers: A Captive's Tale, Vanderbilt University Press, p. 122, ISBN 0826514707

- Jaques, Tony (2007), Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A-E, Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 32, ISBN 978-0313335372

- Fumerton, Patricia (2006), Unsettled: The Culture of Mobility and the Working Poor in Early Modern England, University of Chicago Press, p. 85, ISBN 0226269558

- Today's Zaman. "Turks in northern Africa yearn for Ottoman ancestors". Archived from the original on 2011-03-13. Retrieved 2012-03-18.

- Knauss, Peter R. (1987), The Persistence of Patriarchy: Class, Gender, and Ideology in Twentieth Century Algeria, Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 19, ISBN 0275926923

- Killian, Caitlin (2006), North African Women in France: Gender, Culture, and Identity, Stanford University Press, p. 145, ISBN 0804754209

- Murray, Roger; Wengraf, Tom (1963), "The Algerian Revolution (Part 1)", New Left Review, 1 (22): 41

- McMurray, David Andrew (1992), "The Contemporary Culture of Nador, Morocco, and the Impact of International Labor Migration", University of Texas: 390

- Cezayir Türkleri: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nun etkili mirası, Sputnik (news agency), 2015,

2014 nüfus sayımlarında çıkan 38 milyon kişilik sonuç baz alındığında, 760 bin ile 9,5 milyon arasında bir Türk azınlıktan söz etmek mümkün. 760 bin rakamı, saf Türkleri işaret ediyorken, diğer kaynakların rakamı ise farklı halklarla ‘karışmış' Cezayir Türkleri'ne ait olabilir. Bunların yanında, özellikle İngiltere ve Fransa'da olmak üzere, Avrupa ülkelerinde de binlerce Cezayir Türkü bulunduğunu belirtmek gerekiyor.

- UNESCO (2009), Diversité et interculturalité en Algérie (PDF), UNESCO, p. 9, archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-07-25.

- Current Notes on International Affairs, 25, Department of Foreign Affairs (Australia), 1954, p. 613,

In Algeria and Tunisia, however, the Arab and Berber elements have become thoroughly mixed, with an added strong Turkish admixture.

- Algeria: Post Report, Foreign Service Series 256, U.S. Department of State (9209), 1984, p. 1,

Algeria's population, a mixture of Arab, Berber, and Turkish in origin, numbers nearly 21 million and is almost totally Moslem.

- Rajewski, Brian (1998), Africa, Volume 1: Cities of the World: A Compilation of Current Information on Cultural, Geographical, and Political Conditions in the Countries and Cities of Six Continents, Gale Research International, p. 10, ISBN 081037692X,

Algeria's population, a mixture of Arab, Berber, and Turkish in origin, numbered approximately 29 million in 1995, and is almost totally Muslim.

- Ruedy, John Douglas (2005), Modern Algeria: The Origins and Development of a Nation, Indiana University Press, p. 22, ISBN 0-253-21782-2,

Renewed through the generations by continuous recruitment of Anatolian Turks...

- Roberts, Hugh (2014), Berber Government: The Kabyle Polity in Pre-colonial Algeria, I.B.Tauris, p. 198, ISBN 978-0857736895,

Most sources stress the Anatolian origins of the core of the janissaries in Algeria....it was Kheireddine who proposed and got the Ottoman Sultan to agree that any Turk who was not a janissary or a son of a Christian but who wished to emigrate from Anatolia to Algiers would be entitled to belong to the corps of the janissaries and enjoy all the rights and privileges of this status.

- Stone, Martin (1997), The Agony of Algeria, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, p. 29, ISBN 1-85065-177-9.

- Milli Gazete. "Levanten Türkler". Archived from the original on 2010-02-23. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- Shuval 2000, 330.

- Miltoun, Francis (1985), The spell of Algeria and Tunisia, Darf Publishers, p. 129, ISBN 1850770603,

Throughout North Africa, from Oran to Tunis, one encounters everywhere, in the town as in the country, the distinct traits which mark the seven races which make up the native population: the Moors, the Berbers, the Arabs, the Negreos, the Jews, the Turks and the Kouloughlis… descendants of Turks and Arab women.

- Goodman, Jane E. (2005), Berber Culture on the World Stage: From Village to Video, Indiana University Press, p. 7, ISBN 0253111455,

From early on, the French viewed North Africa through a Manichean lens. Arab and Berber became the primary ethnic categories through which the French classified the population (Lorcin 1995: 2). This occurred despite the fact that a diverse and fragmented populace comprised not only various Arab and Berber tribal groups but also Turks, Andalusians (descended from Moors exiled from Spain during the Crusades), Kouloughlis (offspring of Turkish men and North African women), blacks (mostly slaves or gormer slaves), and Jews.

- Gamm, Niki (2013), The Keys to Oran, Hürriyet Daily News,

How many there are in today’s population is unclear. Estimates range from five percent to ten percent out of a total population of around 37 million

- Hizmetli, Sabri (1953), "Osmanlı Yönetimi Döneminde Tunus ve Cezayir'in Eğitim ve Kültür Tarihine Genel Bir Bakış" (PDF), Ankara Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi, Ankara University, 32: 10,

Bunun açık belgelerinden birisi, aradan birbuçuk yüzyıllık sömürgecilik döneminin geçmiş olmasına rağmen, Cezayirli ve Tunusluların 25 %'nin Türk asıllı olduğunu övünerek söylemesi, sosyal ve kültürel hayatta Türk kültürünün varlığını hissettirmeye devam etmesi, halk dilinde binlerce Türkçe kelimenin yaşamasıdir.

- Ferchiche, Nassima (2016), "Religious Freedom in the Constitutions of the Maghreb", in Durham, W. Cole; Ferrari, Silvio; Cianitto, Cristiana; Thayer, Donlu (eds.), Law, Religion, Constitution: Freedom of Religion, Equal Treatment, and the Law, Routledge, p. 186, ISBN 978-1317107385,

The majority of Algerians observe the Sunni Malekite rite. There are also "Amerites" (Sunnis of Turkish origin), Ibadists (neither Sunni nor Shia) in M'Zab, and brotherhoods mostly in the South.

- Amari, Chawki (2012), Que reste-t-il des Turcs et des Français en Algérie?, Slate Afrique,

Les Turcs ou leurs descendants en Algérie sont bien considérés, ont même une association (Association des Turcs algériens), sont souvent des lettrés se fondant naturellement dans la société...Les Kouloughlis (kulughlis en Turc) sont des descendants de Turcs ayant épousé des autochtones pendant la colonisation (la régence) au XVIème et XVIIème siècle...Ce qu'il reste des Turcs en Algérie? De nombreux éléments culturels, culinaires ou architecturaux, de la musique,... Des mots et du vocabulaire, des noms patronymiques comme Othmani ou Osmane (de l'empire Ottoman), Stambouli (d'Istambul), Torki (Turc) ou des noms de métiers ou de fonctions, qui sont devenus des noms de famille avec le temps.

- Parzymies, Anna (1985), Anthroponymie Algérienne: Noms de Famille Modernes d'origine Turque, Éditions scientifiques de Pologne, p. 109, ISBN 83-01-03434-3,

Parmi les noms de famille d'origine turque, les plus nombreux sont ceux qui expriment une provenance ou une origine ethnique, c.-à-d., les noms qui sont dérivés de toponymes ou d'ethnonymes turcs.

- Shuval, Tal (2000), "The Ottoman Algerian Elite and Its Ideology", International Journal of Middle East Studies, Cambridge University Press, 32 (3): 325, doi:10.1017/S0020743800021127.

- Shuval 2000, 328.

- Shuval 2000, 326.

- Shuval 2000, 327.

- Shuval 2000, 329.

- Alexis Tocqueville, Second Letter on Algeria (August 22, 1837), Bronner, Stephen Eric; Thompson, Michael (eds.), The Logos Reader: Rational Radicalism and the Future of Politics, (University of Kentucky Press, 2006), 205;"This bey, contrary to all custom, was coulougli, meaning the son of a Turkish father and an Arab mother."

- Shuval 2000, 331.

- Ruedy 2005, 35.

- Shuval 2000, 332.

- Shuval 2000, 333.

- Ness, Immanuel; Cope, Zak (2016), The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Imperialism and Anti-Imperialism, Springer, p. 634, ISBN 978-0230392786,

Messali, an Algerian of Turkish origin who resided in Paris, founded in 1926 the first modern movement for Algerian independence

- Jacques, Simon (2007), Algérie: le passé, l'Algérie française, la révolution, 1954-1958, L'Harmattan, p. 140, ISBN 978-2296028586,

Messali Hadj est né le 16 mai 1898 à Tlemcen. Sa famille d'origine koulouglie (père turc et mère algérienne) et affiliée à la confrérie des derquaouas vivait des revenus modestes d'une petite ferme située à Saf-Saf

- Adamson, Fiona (2006), The Constitutive Power of Political Ideology: Nationalism and the Emergence of Corporate Agency in World Politics, University College London, p. 25.

- McDougall, James (2006), History and the Culture of Nationalism in Algeria, Cambridge University Press, p. 158, ISBN 0521843731.

- Kateb, Kamel (2001), Européens: "Indigènes" et juifs en Algérie (1830-1962) : Représentations et Réalités des Populations, INED, pp. 50–53, ISBN 273320145X

- Shinar, Pessah (2004), "The Historical Approach of the Reformist 'Ulama' in the Contemporary Maghrib", Modern Islam in the Maghrib, Max Schloessinger Memorial Foundation, p. 204, ISBN 9657258022

- Pessah 2004, 205.

- Singh, K.R (2013), "North Africa", in Ayoob, Mohammed (ed.), The Politics of Islamic Reassertion, Routledge, p. 63, ISBN 978-1134611102

- Dala, Mustafa (2011). "جزايرس : عائلات جزائرية ترغب في إحياء هويتها التركية". Echorouk El Yawmi. Retrieved 2017-04-11.

- Bencheneb, Rachid (1971), "Les mémoires de Mahieddine Bachtarzi ou vingt ans de théâtre algérien", Revue de l'Occident musulman et de la Méditerranée, 9 (9): 15, doi:10.3406/remmm.1971.1098,

...Mahieddine Bachtarzi, après une longue carrière de ténor, de comédien, d'auteur dramatique et de directeur de troupe, vient de publier la première partie de ses Mémoires1, qui s'étend de 1919 à la veille de la seconde guerre mondiale. A quinze ans, ce fils de bourgeois, d'origine turque...

. - Parzymies 1985, 43.

- Sebbar, Leïla (2010), Voyage en Algéries autour de ma chambre, Suite 15, retrieved 16 July 2017,

mon père et lui sont cousins germains par leurs mères, des sœurs Déramchi, vieilles familles citadines du Vieux Ténès d’origine turque

- Parzymies 1985, 51.

- Parzymies 1985, 42.

- Parzymies 1985, 44.

- Parzymies 1985, 61.

- Parzymies 1985, 62.

- Parzymies 1985, 46.

- Parzymies 1985, 47.

- Parzymies 1985, 48.

- Parzymies 1985, 65.

- Parzymies 1985, 66.

- Parzymies 1985, 63.

- Parzymies 1985, 50.

- Parzymies 1985, 52.

- Parzymies 1985, 54.

- Parzymies 1985, 55.

- Parzymies 1985, 60.

- Parzymies 1985, 57.

- Parzymies 1985, 58.

- Slate Afrique. "Que reste-t-il des Turcs et des Français en Algérie?". Retrieved 2013-09-08.

- Parzymies 1985, 69.

- Parzymies 1985, 64.

- Parzymies 1985, 67.

- Parzymies 1985, 49.

- Parzymies 1985, 68.

- Parzymies 1985, 70.

- Zemouli, Yasmina (2004), "Le nom patronymique d'après l'état civil en Algérie", in Qashshī, Fāṭimah al-Zahrāʼ (ed.), Constantine: une ville, des heritages, Média-plus, p. 87, ISBN 996192214X

- Parzymies 1985, 41.

- Parzymies 1985, 45.

- Parzymies 1985, 53.

- Parzymies 1985, 56.

- Parzymies 1985, 59.

- Yenişehirlioğlu, Filiz (1989), Ottoman architectural works outside Turkey, T.C. Dışişleri Bakanlığı, p. 34, ISBN 9759550105

- Benrabah, Mohamed (2007), "The Language Planning Situation in Algeria", Language Planning and Policy in Africa, Vol 2, Multilingual Matters, p. 49, ISBN 978-1847690111

- Algerian patois delights and disturbs, Al Jazeera, 2006

- Al Turkiyya. "Cezayir deki Türkiye". Archived from the original on 2013-09-27. Retrieved 2013-09-17.

- Gordon, Louis A.; Oxnevad, Ian (2016), Middle East Politics for the New Millennium: A Constructivist Approach, Lexington Books, p. 72, ISBN 978-0739196984,

An Ottoman military class that separated itself from the general Algerian population through language, dress and religious affiliation... Unlike the Maliki Algerian masses, the Ottoman-Algerians remained affiliated with the Hanafi school of Islamic jurisprudence, and went to great lengths to replenish their ranks with Ottoman Turks from Anatolia...

- Cantone, Cleo (2002), Making and Remaking Mosques in Senegal, BRILL, p. 174, ISBN 9004203370,

Octagonal minarets are generally an anomaly in the Maliki world associated with the square tower. Algeria, on other hand had Ottoman influence...

- Migeon, Gaston; Saladin, Henri (2012), Art of Islam, Parkstone International, p. 28, ISBN 978-1780429939,

It was not until the 16th century, when the protectorate of the Grand Master appointed Turkish governors to the regencies of Algiers and Tunis, that some of them constructed mosques according to the Hanefit example. The resulting structures had octagonal minarets...

- Oakes, Jonathan (2008), Bradt Travel Guide: Algeria, Bradt Travel Guides, p. 23, ISBN 978-1841622323.

- Akar, Metin (1993), "Fas Arapçasında Osmanlı Türkçesinden Alınmış Kelimeler", Türklük Araştırmaları Dergisi, 7: 94–95,

Günümüzde, Arap dünyasında hâlâ Türk asıllı aileler mevcuttur. Bunların nüfusu Irak'ta 2 milyon, Suriye'de 3.5 milyon, Mısır'da 1.5, Cezayir'de 1 milyon, Tunus'ta 500 bin, Suudî Arabistan'da 150 bin, Libya'da 50 bin, Ürdün'de 60 bin olmak üzere 8.760.000 civarındadır. Bu ailelerin varlığı da Arap lehçelerindeki Türkçe ödünçleşmeleri belki artırmış olabilir.

- Özkan, Fadime (2015), Deneme Bir İki, Okur Kitaplığı, p. 475, ISBN 978-6054877942,

Cezayir'de Türk rakamlarına göre 600 bin, Fransız rakamlarına göre 2 milyon Türk asıllı Cezayirlinin yaşadığını...

. - Strateji Geliştirme Daire Başkanlığı (2010), "Sosyo-Ekonomik Açıdan Cezayir" (PDF), Gümrük Ve Ticaret Bülteni, Strateji Geliştirme Daire Başkanlığı (3): 35,

Bu sistem ile Osmanlı İmparatorluğunun bu topraklarda hüküm sürdüğü yaklaşık üç yüzyıllık sürede, bir milyon Türk genci Cezayir’e gönderilmiştir. Birçoğu çatışmalar ve savaşlar esnasında ölen bu gençlerden bir bölümünün sağ kalarak soylarını sürdürmekte olduğu düşünülmektedir. Cezayir resmi kaynaklarınca 600-700 bin, Fransız Büyükelçiliği’nce 2 milyon olarak açıklanan Cezayir’deki Türk asıllı vatandaş sayısı, kanaatime göre çok daha fazladır. Zira, Osmanlı İmparatorluğu döneminde gönderilen bir milyon Yeniçeri içerisinden ticaretle uğraşan ve oralardaki bayanlarla evlenerek soyunu devam ettiren çok sayıda gencin mevcut olduğu, bunların da yaklaşık 500 yıl içerisinde çoğaldıkları tahmin edilmektedir. 18. yüzyılda toplam nüfusun içerisinde % 30’luk paya sahip olan Türklerin, günümüzde % 0,2’lik (binde iki) bir paya sahip olması pek açıklayıcı görünmemektedir.

- Britannica (2012), Tlemcen, Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- Stone, Martin (1997), The Agony of Algeria, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, p. 29, ISBN 1-85065-177-9.

- Oakes 2008, 5.

- Oakes 2008, 5 and 61.

- Shrader, Charles R. (1999), The First Helicopter War: Logistics and Mobility in Algeria, 1954-1962, Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 23, ISBN 0275963888

- Oakes 2008, 179.

- Oakes 2008, 170.

- Oakes 2008, 114.

- Les Enfants de Médéa et du Titteri. "Médéa". Retrieved 2012-04-13.

- Bosworth, C.E; Donzel, E. Van; Lewis, B.; Pellat, C.H., eds. (1980), "Kul-Oghlu", The Encyclopaedia of Islam, 5, Brill, p. 366

- Huebner, Jeff (2014), "Oran", in Ring, Trudy (ed.), Middle East and Africa: International Dictionary of Historic Places, Routledge, p. 560, ISBN 978-1134259861

- Appiah, Anthony; Gates, Henry Louis (2010), Encyclopedia of Africa, Volume 1, Oxford University Press, p. 475, ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9.

- Institut des hautes-études marocaines (1931). Hespéris: archives berbères et bulletin de l'Institut des hautes-études marocaines. 13. Emile Larose. Retrieved 2015-04-01.

- Garvin, James Louis (1926), Encyclopædia Britannica, 1 (13 ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica, p. 94

- Vogelsang-Eastwood, Gillian (2016), "Embroidery from Algerria", Encyclopedia of Embroidery from the Arab World, Bloomsbury Publishing, p. 226, ISBN 978-0857853974.

- Rozet, Claude (1850), Algérie, Firmin-Didot, p. 107.

- Ameur, Kamel Nait (2007), "Histoire de Tizi Ouzou : L'indélébile présence turque", Racines-Izuran, 17 (5)

- Cheriguen, Foudil (1993), Toponymie algérienne des lieux habités (les noms composés), Épigraphe, pp. 82–83.

- Déjeux, Jean (1984), Dictionnaire des Auteurs Maghrébins de Langue Française, KARTHALA Editions, p. 121, ISBN 2-86537-085-2,

HACIANE, Mustapha Né en 1935 à Rouiba dans une famille d'origine turque. A 17 ans, il écrit au lycée des poèmes engagés...Réside à Paris.

. - Koroghli, Ammar (2010), EL DJAZAÎR : De la Régence à l'Istiqlal, Sétif Info.

- Communities and Local Government (2009), The Algerian Muslim Community in England: Understanding Muslim Ethnic Communities (PDF), Communities and Local Government, p. 34, ISBN 978-1-4098-1169-5, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-20.

- Communities and Local Government 2009, 53.

- Communities and Local Government 2009, 22.

- Ameskane, Mohamed (2005). "Décès du troubadour de l'amour: Salim Halali". La Gazette du Maroc.

Son père est d'origine turque et sa mère (Chalbia) une judéo-berbère d'Algèrie.

- VH magazine (2010). "Salim Halali: Le roi des nuits Csablancaises" (PDF). p. 66. Retrieved 2013-03-27.

Salim Hilali, est né un 30 juillet 1920 à Bône (Annaba), à la frontière algéro-tunisienne. Il est issu d’une famille de Souk Ahras, berceau des plus grandes tribus Chaouia, les Hilali, descendants de la Kahéna la magnifique, la prêtresse aurésienne qui régna sur l’Ifriquia (actuel Maghreb) avant la conquête arabe. Son père est d’origine turque et sa mère (Chalbia) une judéo-berbère d’Algérie.

- Benjamin, Roger (2004), "Orientalism, modernism and indigenous identity", in Edwards, Steve; Wood, Paul (eds.), Art of the Avant-Gardes, Yale University Press, p. 100, ISBN 0-300-10230-5,

Mohammed Racim...was born into an Algerine family of artisans of Turkish origin... Like his older brother, Omar, he was schooled to enter the family workshop...

. - "France Culture à l'heure algérienne". Télérama. 2012. Retrieved 2017-05-03.

Ecouter la parole libre de Wassyla Tamzali, c'est approcher de près toute ... Née dans une famille d'origine turque et espagnole

- Afrique-Asie, Issues 178-190: Sports, Société d'Éditions Afrique, Asie, Amérique Latine, 1979, p. 414,

Les Jeux méditerranéens vont s'ouvrir à Alger, quand on apprend que le perchiste français Patrick Abada a émis le souhait de ... La vérité est pourtant toute simple : Abada est d'une vieille famille algéroise (d'origine turque) dont de ...

. - Tahri, Hamid (2020), La saga familiale des artistes peintres algérois passeurs de messages, El Watan.

- Denaud, Patrick (1998), Algerie: Le Fis: Sa direction parle, L'Harmattan, p. 30, ISBN 2296355137,

Ghemati Abdelkrim Né à Cherchell en 1961, d'une famille sans doute d'origine turque,...

. - Benkada, Saddek (1999), "Elites émergentes et mobilisation de masse L'affaire du cimetière musulman d'Oran (février-mai 1934)", Emeutes et mouvements sociaux au Maghreb: perspective comparée, KARTHALA Editions, p. 80, ISBN 2865379981,

Benaouda Hadj Hacène Bachterzi, né et décédé à Oran (1894-1958). Homme politique et publiciste, il appartenait à l'une des plus anciennes familles algéro-turques.

. - Vidal-Bué, Marion (2000), Alger et ses peintres, 1830-1960, Paris-Méditerranée, p. 249, ISBN 2842720954,

BENABOURA HACÈNE Alger 1898 - Alger 1961 Descendant d'une famille de notables d'origine turque demeurant à Alger depuis les frères Barbe- rousse, Benaboura est peintre en carrosserie avant de se livrer à sa passion pour la peinture.

. - Cheurfi, Achour (2001), La Classe Politique Algérienne (de 1900 à nos jours): Dictionnaire Biographique, University of Michigan, p. 73, ISBN 9961-64-292-9,

BENCHENEB Mohamed (1869-1929)... Mohamed ben Larbi ben Mohamed Bencheneb est né le 26 octobre 1869 à Ain Dheheb (Takbov, Médéa) au sein d'une famille dont les ancêtres, originaires de Brousse (Turquie)...

. - Tahri, Hamid (2012), Mohamed Bencheneb raconté par son fils, El Watan,

Bencheneb est père de 4 filles et 5 garçons, Saâdedine (1907), Larbi (1912), Rachid (1915), Abdelatif (1917) et le dernier Djaffar.

. - ALI BENCHENEB (2003-2007), Réseau Canopé,

Ali Bencheneb est né le 13 juin 1947 à Alger dans une famille d'universitaires (son grand-père, Mohamed Bencheneb, a été un enseignant et un humaniste reconnu au début du XXe siècle).

. - Cheurfi, Achour (2004), Écrivains algériens: dictionnaire biographique, Casbah éditions, p. 77, ISBN 9961643984,

BEN CHERIF Lakhdar (1899-1967). - Poète populaire. Lakhdar B. Cherif Al Imam B. Ibrahim B. Ahmed naquit à El-Oued. Sa mère, d'origine turque, s'appelait Mériem bent Salah Khiari.

. - Benbelgacem, Ali (2015), L'émergence de l'Algérie moderne, La Nouvelle République, retrieved 6 August 2017,

le parti politique du Docteur Bendjelloul (d'origine turque mais natif de Constantine)

. - Maison "Dar Bengui", La Nouvelle République, 2017,

Selon nos sources, cette maison d'époque ottomane appartenait à El Haj Omar Bengui, suite à son mariage avec la fille de Mostefa Ben Karim. Cette dernière était une notable de la famille Bey Kara Ali une famile d'origine Turque, proche du Bey Brahim El Greitli (l'avant dernier Bey de Constantine de l'Empire Ottoman). Leur fils, Slimane Bengui, était manufacturier de tabac, au coeur de la médina. En 1893, Slimane Bengui devient directeur du premier journal algérien de langue française, « El Hack » (« La Vérité », en arabe),

. - Gallissot, René; Bouayed, Anissa (2006), Algérie: engagements sociaux et question nationale : de la colonisation à l'indépendance de 1830 à 1962, Volume 8, Éditions de l'Atelier, p. 73, ISBN 2708238655,

Né le 23 octobre 1903 à Tlemcen, Djelloul Benkalfat est issu d'une vieille famille dite turque qui a donné beaucoup d'artisans d'art à la ville.

. - Aggarwal, Jatendra M., ed. (1962), "Profile. PREMIER. REN. KHEDDA, Ben Youcef Ben Khedda", Indian Foreign Affairs, 5: 4,

Turkish by origin, journalist by circumstances, Ben Khedda was the "most wanted man" when General Jacques Massu was confronted to deal with the terrorist activities of the F.L.N, in Algiers.

. - Cheurfi, Achour (2001), La Classe Politique Algérienne (de 1900 à nos jours): Dictionnaire Biographique, University of Michigan, p. 96, ISBN 9961-64-292-9,

BENSMANIA Abdelhalim (1866-1933) Né à Alger dans une famille d'origine turque, son père Ali Ben Abderrahmane Khodja, dernier muphti malékite d'Alger, attacha une grande importance à son éducation morale et religieuse.

. - Conférence sur cheikh Abderrahmane El Djillali. : Un niveau d'érudition élevé, El Watan, 2015, retrieved 5 August 2017,

Abdelhalim Ben Smaya, Algérois d'origine turque, un des prestigieux notables et érudits d' Alger...

. - Meynier, Gilbert (2001), "Le FLN/ALN dans les six wilayas: etude comparee", Militaires et guérilla dans la guerre d'Algérie, Editions Complexe, p. 156, ISBN 2870278535,

Dans d'autres régions d'Algérie, cela a existé : par exemple, le Kouloughli Ben Tobbal dans le Nord-Constanti- nois, ...

. - Dib, Souhel (2007), Pour une poétique du dialectal maghrébin: expression arabe, Editions ANEP, p. 99, ISBN 978-9947213186,

BEN-TRIKI Ahmad (A) Né en 1650 à Tlemcen, Turc d'origine par son père, il meurt, centenaire...

. - Kadi, Nadir (2015), Histoire / Mémoire / Edition: Abderrahmane Berrouane raconte le MALG chez Barzakh, Reporters,

né à Relizane en juin 1929 d’une mère « d’origine arabo-turque »

. - Establet, Colette (1992), "Les Gaba, les Chaouch, deux dynasties de caïds dans l'Algérie coloniale, de 1851 à 1912 (Cercle de Tébessa)", Cahiers de la Méditerranée, 45 (1): 52, doi:10.3406/camed.1992.1076,

Ahmed Chaouch... est Kouloughli, descendant des Turcs ; on sait que son père et sa famille ont servi sous les Turcs.

. - Tocqueville, Alexis de (2006), "Second Letter on Algeria (August 22, 1837)", in Bronner, Stephen Eric; Thompson, Michael (eds.), The Logos Reader: Rational Radicalism and the Future of Politics, University Press of Kentucky, p. 205, ISBN 0813191483.

- Cezayir Türkleri: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nun etkili mirası, Sputnik (news agency), 2015,

Türklerin üst düzey görevlerde bulunması, yaşanan gelişmelerin sebeplerinden biri. Bu isimler arasında, farklı gruplarda olmalarına rağmen, Cezayir ordusunun gizli servisi DRS'nin başında Muhammed Meden, halef Atman Tartag ve Devlet Başkanı Abdülaziz Buteflika yer alıyor.

- Chellabi, Leïla (2008), Autoscan: Autobiographie d'une intériorité, LCD Médiation, p. 237, ISBN 978-2909539751,

Mon père, né Algérien d'origine turque, a quitté l'Algérie pour le Maroc où il a fait sa vie après être devenu, par choix, français. Mais à chaque démarche on le croit d'abord marocain puis on sait qu'il est d'origine algérienne et turque, cela se complique.

. - Elwatan (2009). "Cheikh Abdelkrim Dali . Monument de la musique algérienne : Le rossignol passeur". Retrieved 2012-03-23.

- Ruedy 2005, 137.

- Daughter of Messali Hadj (who is paternally of Turkish origin)

- Spiaggia, Josette (2012), J'ai six ans: et je ne veux avoir que six ans, Editions du Félibre Laforêt, p. 104, ISBN 978-2953100990,

Mourad Kaoua (par la suite député d'Alger de 1958 à 1962) d'origine turque...

. - Panzac, Daniel (2005), Barbary Corsairs: The End of a Legend, 1800-1820, BRILL, p. 224, ISBN 90-04-12594-9.

- S, Fodil (2016), Une initiative qui mérite des encouragements Création d'une fonderie d'art à Jijel, El Watan, retrieved 5 August 2017,

C'est dans cette coquette ville côtière de Jijel qu'est né en 1951 Mohamed-Réda Benabdallah Khodja, deux ans après l'installation de sa famille constantinoise d'origine turque, dans ce plaisant littoral méditerranéen.

. - Carlier, Omar (2007), "'émergence de la culture moderne de l'image dans l'Algérie musulmane contemporaine", Sociétés & Représentations, 2 (24): 340,

le Dr Ben Lerbey, issu d’une vieille famille turque d’Alger, peut-être le premier médecin algérien

. - McDougall, James (2006), History and the Culture of Nationalism in Algeria, Cambridge University Press, p. 158, ISBN 0-521-84373-1.

- Ouaglal, Djamel (2009), InfoSoir s'invite chez les Magdy, L'exemple de réussite d'une famille mixte, Info Soir, retrieved 5 August 2017,

Ahmed Magdy semble très fier, même s'il se sent beaucoup plus Egyptien. «Je trouve que c'est un privilège d'être doté d'une double nationalité. Il faut savoir que ce n'est pas un fait nouveau chez nous. Ma grand-mère paternelle est d'origine turque et mon grand-père est Egyptien, alors que mes grands- parents du côté maternel ont des origines arabe et berbère.

. - Kauffer, Rémi (2015), Histoire Mondiale des Services Secrets, Librairie Académique Perrin, ISBN 978-2262064570,

La second objectif de Lang s'appelle Abdelmalek Ben Mohieddine. Bien que sujet algérien, cet officier se réclame de la Turquie. Fils de l'émir Abdelkader, il appartient en effet au clan de celui qui fut l'âme de la résistance algérienne à la colonisation française.

. - Kitchell, Liza Parker (1998), The development of Kabyle song during the twentieth century, University of Wisconsin, p. 52,

Cheikh Nador was born in Algiers in 1874 and was of Turkish origins

. - Bey, A Salah (2010), L'exclusivité "Les splendeurs du Mouloudia, 1921 -1956", Info Soir, retrieved 5 August 2017,

sachant que d'autres avant lui avaient mis l'ancrage à l'image de Benmahmoud Omar Ali Raïs, d'origine turque, considéré comme le père du sport algérien à travers l'Avant-Garde d' Alger en 1895.

. - Gilles, Alexandre (2019), AU MAROC, ATLAS ELECTRONIC TISSE UN LIEN ENTRE PATRIMOINE MILLÉNAIRE ET MUSIQUE DU FUTUR, Mixmag,

Hadj Sameer... Français d’origine algéro-turque

. - Rahal, Malika (2010), Ali Boumendjel, 1919-1957: une affaire française, une histoire algérienne, Vol 5, Belles lettres, p. 97, ISBN 978-2251900056,

Maître Kaddour Sator est, comme lui, très proche de Ferhat Abbas au sein de l'UDMA : il écrit dans La République algérienne mais appartient plutôt à la génération d'Ahmed, et est issu d'une des grandes familles algéroise d'origine turque.

. - Diff, Fazilet (2013), Mohamed Sfinja (1844-1908), maître Andalou : l'ange gardien, El Watan, retrieved 5 August 2017,

Au lendemain de la prise d'Alger, le recensement des familles d'Alger compta les Sfindja, d'origine turque, parmi les plus riches de la ville.

- Forzy, Guy (2002), Ça aussi -- c'était De Gaulle, Volume 2, Muller édition, p. 134, ISBN 2904255494,

La secrétaire d'Etat musulmane Nafissa Sidkara, d'une vieille famille d'origine turque établie en Algérie, et caution involontaire, comme son frère le Docteur Sid Cara lui aussi membre du gouvernement français...

. - "L'artiste aux doigts d'or". La Nouvelle République. 2007.

Mustapha Skandrani a vu le jour le 17 novembre 1920, à la Casbah d’Alger. Selon lui, ses origines seraient d’Iskander, ville turque.

- Benzerga, Mohamed. "Hommage à cheikh Mustapha Stambouli : l'imam qui n'aimait pas les spéculateurs!". Djazairess. Retrieved 2017-04-27.

cheikh Mustapha Stambouli appartenait à une famille de lettrés d'origine turque et de rite hanafite

- Mokhtari, Rachid (2002), Cheikh El Hasnaoui: La voix de l'errance: Essai, Chihab, p. 24, ISBN 9961634608.

- لقب بن نبي انقرض من الجزائر ومفكر العصر شجرة بلا غصون. جريدة الشروق. 5 أغسطس 2016

Bibliography

- Adamson, Fiona (2006), The Constitutive Power of Political Ideology: Nationalism and the Emergence of Corporate Agency in World Politics, University College London

- Adem, Ismail (2004), Küçük ve Orta Ölçekli İşletmeleri Geliştirme ve Destekleme Başkanlığı Cezayir Ülke Raporu (PDF), KOSGEB, archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-11-21.

- Appiah, Anthony; Gates, Henry Louis (2010), Encyclopedia of Africa, Volume 1, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9.

- Bencheneb, Rachid (1971), "Les mémoires de Mahieddine Bachtarzi ou vingt ans de théâtre algérien", Revue de l'Occident musulman et de la Méditerranée, 9 (9): 15–20, doi:10.3406/remmm.1971.1098

- Benjamin, Roger (2004), "Orientalism, modernism and indigenous identity", in Edwards, Steve; Wood, Paul (eds.), Art of the Avant-Gardes, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-10230-5.

- Boyer, Pierre (1970), "Le problème Kouloughli dans la régence d'Alger", Revue de l'Occident musulman et de la Méditerranée, 8: 77–94, doi:10.3406/remmm.1970.1033

- Cheurfi, Achour (2001), La Classe Politique Algérienne (de 1900 à nos jours): Dictionnaire Biographique, University of Michigan, ISBN 9961-64-292-9.

- Communities and Local Government (2009), The Algerian Muslim Community in England: Understanding Muslim Ethnic Communities (PDF), Communities and Local Government, ISBN 978-1-4098-1169-5, archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-20.

- Déjeux, Jean (1984), Dictionnaire des Auteurs Maghrébins de Langue Française, KARTHALA Editions, ISBN 2-86537-085-2.

- Dokali, Rachid (1974), Les mosquées de la période Turque à Alger, University of Michigan: SNED, ASIN B0000EA150.

- Hizmetli, Sabri (1953), "Osmanlı Yönetimi Döneminde Tunus ve Cezayir'in Eğitim ve Kültür Tarihine Genel Bir Bakış" (PDF), Ankara Üniversitesi İlahiyat Fakültesi Dergisi, 32: 1–12

- McDougall, James (2006), History and the Culture of Nationalism in Algeria, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-84373-1.

- Oakes, Jonathan (2008), Bradt Travel Guide: Algeria, Bradt Travel Guides, ISBN 978-1841622323

- Oxford Business Group (2008), The Report: Algeria 2008, Oxford Business Group, ISBN 978-1-902339-09-2.

- Panzac, Daniel (2005), Barbary Corsairs: The End of a Legend, 1800-1820, BRILL, ISBN 90-04-12594-9.

- Parzymies, Anna (1985), Anthroponymie Algérienne: Noms de Famille Modernes d'origine Turque, Éditions scientifiques de Pologne, ISBN 83-01-03434-3.

- Rozet, Claude (1850), Algérie, Firmin-Didot.

- Ruedy, John Douglas (2005), Modern Algeria: The Origins and Development of a Nation, Indiana University Press, ISBN 0-253-21782-2.

- Saoud, R. (2004), The Impact of Islam on Urban Development in North Africa (PDF), Foundation for Science Technology and Cilisation.

- Shuval, Tal (2000), "The Ottoman Algerian Elite and Its Ideology", International Journal of Middle East Studies, Cambridge University Press, 32 (3): 323–344, doi:10.1017/s0020743800021127

- Shuval, Tal (2002), "Remettre l'Algérie à l'heure ottomane. Questions d'historiographie", Revue du monde musulman et de la Méditerranée (95–98): 423–448, doi:10.4000/remmm.244

- Stone, Martin (1997), The Agony of Algeria, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, ISBN 1-85065-177-9.

- Tocqueville, Alexis de (2006), "Second Letter on Algeria (August 22, 1837)", in Bronner, Stephen Eric; Thompson, Michael (eds.), The Logos Reader: Rational Radicalism and the Future of Politics, University Press of Kentucky, ISBN 0813191483.

- Toussaint-Samat, Maguelonne (2009), "Coffee and Politics", A History of Food, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-1-4443-0514-2.

- Turkish Embassy in Algeria (2008), Cezayir Ülke Raporu 2008, Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- UNESCO (2009), Diversité et interculturalité en Algérie (PDF), UNESCO, archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-07-25.