Khalaj people

The Khalaj (Bactrian Xalaso; Pashto: خلجیان, romanized: Khalajyān; Persian: خلجها, romanized: Xalajhâ) are classified as a Turkic tribe.[1] Medieval Muslim scholars considered the tribe to be one of the earliest to cross the Amu Darya from Central Asia into present-day Afghanistan. The Khalaj were described as sheep-grazing nomads in Ghazni, Qalati Ghilji, and the surrounding districts, who had a habit of wandering through seasonal pastures.

In Iran, they still speak Khalaj language, which is classified as Turkic, although most of them are Persianized.[2] In Afghanistan, the Ghilji tribe of Pashtuns may have descended from the Khalaj people.[3][4][5][6]

Etymology

According to linguist Gerhard Doerfer, Mahmud al-Kashgari was the first person mentioning the Khalaj people in his Dīwān Lughāt al-Turk:

- "The twenty twos call them "Kal aç" in Turkic languages. This means "Stay hungry". Later, they were called "Xalac"."[7]

- "Oguzs and Kipchaks translate "x" to k". They are a group of "Xalac". They say "xızım", whereas Turks say "kızım" (my daughter). And again other Turks say "kande erdinğ", whereas they say "xanda erdinğ", this means "where were you?" [8]

Turkologist Yury Zuev stated that *Qalač resulted from *Halač, owing to the sound-change of prothetic *h- to *q-, typical in many medieval Turkic dialects, and traced Halač's etymology back to ala, alach, alacha "motley, piebald".[9]

However, according to historian V. Minorsky, the ancient Turkic form of the name was indeed Qalaj (or Qalach), but the Turkic /q/ changed to /kh/ in Arabic sources (Qalaj > Khalaj). Minorsky added: "Qalaj could have a parallel form *Ghalaj." This word yielded Ghəljī in Pashto, which was used for the Pashtun Ghilji tribe centered around Ghazni and Qalati Ghilji.[4]

Origin

Ilhanate's statesman and historian Rashid-al-Din Hamadani mentions the Khalaj tribe in his Jami' al-tawarikh as part of the Oghuz (Turkmen) people:

"Over time, these peoples were divided into numerous clans, [and indeed] in every era [new] subdivisions arose from each division, and each for a specific reason and occasion received its name and nickname, like the Oghuz, who are now generally called the Turkmens [Turkman], they are also divided into Kipchaks, Kalach, Kanly, Karluk and other tribes related to them ".[10]

However, some historians, including 20th-century Josef Markwart and 10th-century al-Khwarizmi, consider the Khalaj to be remnants of the Hephthalite confederacy, therefore originally Iranians.[11][12][13][14]

The Khalaj might have later been incorporated into the Western Turkic khaganate, as Hèluóshī (賀羅施), mentioned besides Türgesh (Tūqíshī 突騎施),[15] before regaining independence after the collapses of the Western Turkic and the Türgesh khaganates. Groups of the Khalaj people migrated into Persia beginning with the invasions of the Seljuq Turks, during the 11th century. From there, a branch of them migrated to the Azerbaijan region, where they supposedly picked up greater Turkic influence in their language. However, the Khalaj are very few in Iranian Azerbaijanis today. Sometime shortly prior to the time of Timur (1336-1405), a branch of Khalaj migrated to the area southwest of Saveh in the Markazi Province, which is where a large branch of the Khalaj are located today.[1] However, today, the Khalaj people also identify as Persians despite still speaking their local Turkic language. This is due to undergoing processes of Persianization starting in the mid 20th century.[2]

Discussing their relationship with Karluks, Minorsky and Golden noted that the Khalaj and Karluks were often confused by medieval Muslim authors, as their names were transcribed almost similarly in Arabic.[16] Even so, Kitāb al-Masālik w’al- Mamālik's author Ibn Khordadbeh distinguished Khalajs from Karluks, though he mentioned that both groups lived beyond the Syr Darya of the Talas; Muhammad ibn Najib Bakran wrote in his Jihān-nāma (c. 1200-20) that "by mistake (in writing) the people called the Khallukh Khalaj."[17]

History

Medieval Muslim scholars, including 9th-10th century geographers Ibn Khordadbeh and Istakhri, narrated that the Khalaj were one of the earliest tribes to have crossed the Amu Darya from Central Asia and settled in parts of present-day Afghanistan, especially in the Ghazni, Qalati Ghilji (also known as Qalati Khalji), and Zabulistan regions. Mid-10th-century book Hudud al-'Alam described the Khalaj as sheep-grazing nomads in Ghazni and the surrounding districts, who had a habit of wandering through seasonal pastures.

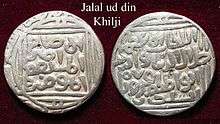

11th-century book Tarikh Yamini, written by al-Utbi, stated that when the Ghaznavid Emir Sabuktigin defeated the Hindu Shahi ruler Jayapala in 988, the Khalaj and Pashtuns (Afghans) between Laghman and Peshawar, the territory he conquered, surrendered and agreed to serve him. Al-Utbi further stated that Khalaj and Pashtun tribesmen were recruited in significant numbers by the Ghaznavid Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni (999–1030) to take part in his military conquests, including his expedition to Tokharistan.[18] The Khalaj later revolted against Mahmud's son Sultan Mas'ud I of Ghazni (1030–1040), who sent a punitive expedition to obtain their submission. In 1197, Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji, a Khalaj general from Garmsir, Helmand in the army of the Ghurid Sultan Muhammad of Ghor, captured Bihar in India, and then became the ruler of Bengal, beginning the Khalji dynasty of Bengal (1204-1227). During the time of the Mongol invasion of Khwarezmia, many Khalaj and Turkmens gathered in Peshawar and joined the army of Saif al-Din Ighraq, who was likely a Khalaj himself. This army defeated the petty king of Ghazni, Radhi al-Mulk. The last Khwarazmian ruler, Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu, was forced by the Mongols to flee towards the Hindu Kush. Ighraq's army, as well as many other Khalaj and other tribesmen, joined the Khwarazmian force of Jalal ad-Din and inflicted a crushing defeat on the Mongols at the 1221 Battle of Parwan. However, after the victory, the Khalaj, Turkmens, and Ghoris in the army quarreled with the Khwarazmians over the booty, and finally left, soon after which Jalal ad-Din was defeated by Genghis Khan at the Battle of the Indus and forced to flee to India. Ighraq returned to Peshawar, but later Mongol detachments defeated the 20,000–30,000 strong Khalaj, Turkmen, and Ghori tribesmen who had abandoned Jalal ad-Din. Some of these tribesmen escaped to Multan and were recruited into the army of the Delhi Sultanate.[19] Jalal-ud-din Khalji (1290-1296), who belonged to the Khalaj tribe from Qalati Khalji, founded the Khalji dynasty, which replaced the Mamluks and became the second dynasty to rule the Delhi Sultanate. 13th-century Tarikh-i Jahangushay, written by historian Ata-Malik Juvayni, narrated that a levy comprising the "Khalaj of Ghazni" and Pashtuns were mobilized by the Mongols to take part in a punitive expedition sent to Merv in present-day Turkmenistan.[4]

Transformation of the Afghan Khalaj

The Khalaj were sometimes mentioned alongside Pashtun tribes in the armies of several local dynasties, including the Ghaznavids (977–1186).[20] Many of the Khalaj of the Ghazni and Qalati Ghilji region became assimilated into the local Pashto-speaking population and they likely formed the core of the Pashtun Ghilji tribe.[3] They intermarried with the local Pashtuns and adopted their manners, culture, customs, and practices, also bringing their customs and culture to India where they established the Khalji dynasty of Bengal (1204–1227) and the Khalji dynasty of Delhi (1290–1320).[21] Minorsky noted: "In fact, there is absolutely nothing astonishing in a tribe of nomad habits changing its language. This happened with the Mongols settled among Turks and probably with some Turks living among Kurds."[4] Because of their language shift and Pashtunization, the Khalaj were treated as Pashtuns (Afghans) by the Turkic nobles of the Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526).[22][23][24]

Just before the Mongol invasion, Najib Bakran's geography Jahān Nāma (c. 1200-1220) described the transformation that the Khalaj tribe was going through:

The Khalaj are a tribe of Turks who from the Khallukh limits migrated to Zabulistan. Among the districts of Ghazni there is a steppe where they reside. Then, on account of the heat of the air, their complexion has changed and tended towards blackness; the tongue too has undergone alterations and become a different language.

— Najib Bakran, Jahān Nāma

Notable people from the Khalaj tribe

- Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji, founder of the Khalji dynasty of Bengal (1204–1227)

- Jalal-ud-din Khalji, founder of the Khalji dynasty of Delhi

- Alauddin Khalji, most powerful emperor of the Khalji dynasty of Delhi

See also

References

- "ḴALAJ i. TRIBE" - Encyclopaedia Iranica, December 15, 2010 (Pierre Oberling)

- "ḴALAJ ii. Ḵalaji Language" - Encyclopaedia Iranica, September 15, 2010 (Michael Knüppel)

- Pierre Oberling (15 December 2010). "ḴALAJ i. TRIBE". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 4 July 2020.

Indeed, it seems very likely that [the Khalaj] formed the core of the Pashto-speaking Ghilji tribe, the name [Ghilji] being derived from Khalaj.

- The Khalaj West of the Oxus, by V. Minorsky: Khyber.ORG. Archived June 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine; excerpts from "The Turkish Dialect of the Khalaj", Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, Vol 10, No 2, pp 417-437 (retrieved 10 January 2007).

- Sunil Kumar (1994). "When Slaves were Nobles: The Shamsi Bandagan in the Early Delhi Sultanate". Studies in History. 10 (1): 23–52. doi:10.1177/025764309401000102.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Peter Jackson (2003). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-521-54329-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Divanü Lügat-it – Türk, translation by Atalay Besim, TDK Press 523, Ankara, 1992, Volume III, page 415

- Divanü Lügat-it – Türk, translation by Atalay Besim, TDK Press 523, Ankara, 1992, Volume III, page 218

- Zuev, Yu. A. (2002) Early Türks: Sketches of history and ideology, Almaty. p. 144

- Hamadani, Rashid-al-Din (1952). "Джами ат-Таварих (Jami' al-tawarikh)". USSR Academy of Sciences.

-

- Denis Sinor (1990). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, volume 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521243049. Retrieved 2017-08-19.

"The relative abundance of data norwithstanding, we have but a very fragmentary picture of Hephthalite civilization.There is no consensus con- cerning the Hephthalite language, though most scholars seem to think that it was Iranian.The Pei shih at least clearly states that the language of the Hephthalites differs from those of the High Chariots, of the Juan-juan and of the "various Hu a rather vague term which, in this context, probably refers to some Iranian peoples... According to the Liang shu the Hephthalites worshiped Heaven and also fire a clear reference to Zoroastrianism."

- University of Indiana (1954). "Asia Major, volume 4, part 1". Institute of History and Philology of the Academia Sinica. Retrieved 2017-08-19.

"Concerning the Hephthalites, Enoki Kazuo stresses that their place of origin was to the north of the Hindu Kush mountain range and that they were of Iranian stock he rejects the view that they were of Altaic origin, with Turkish connections."

- Robert L. Canfield (2002). Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press P. 272.pp.49. ISBN 9780521522915. Retrieved 2017-08-19.

"One cannot go into details here about that dark period of Central Asian history from the time of the Kushans down the coming of the Arabs, but one may suggest that the beginning of this period saw the last waves of Iranian-speaking nomads moving to the south, to be replaced by the Turkic-speaking nomads beginning in the late fourth century.... but our information about them, known in Classical and Islamic sources as the Chionites and Hephthalites, is so meager that much confusion has reigned regarding their origins and nature.Just as later nomadic empires were confederations of many peoples, we may tentatively propose that the ruling groups of these were, or at least included, Turkic-speaking tribesmen from the east and north, although most probably the bulk of the people in the confederation ofChionites and then Hephthalites spoke an Iranian language.In this case, as normal, the nomads adopted the written language, institutions, and culture of the settled folk.To call them "Iranian Huns" as Gobl has done is not infelicitous, for surely the bulk of the population ruled by the Chionites and Hephthalites was lranian (Gobl 1967:ix). But this was the last time in the history ofCentral Asia that Iranian-speaking nomads played any role; hereafter all nomads would speak Turkic languages and the millennium-old division between settled Tajik and nomadic Turk would obtain."

- Denis Sinor (1990). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, volume 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521243049. Retrieved 2017-08-19.

- M. A. Shaban, "Khurasan at the Time of the Arab Conquest", in Iran and Islam, in memory of Vlademir Minorsky, Edinburgh University Press, (1971), p481; ISBN 0-85224-200-X.

- "The White Huns – The Hephthalites", Silk Road

- Enoki Kazuo, "On the nationality of White Huns", 1955

- Stark, Sören. "Türgesh Khaganate, in: Encyclopedia of Empire, ed. John M. McKenzie et al. (Wiley Blackwell: Chichester/Hoboken 2016)". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Golden, Peter B. (1992). An Introduction to the History of the Turkic People. Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden. p. 387

- Minorsky, V. "Commentary" on "§15. The Khallukh" and "§24. Khorasian Marches" in Ḥudūd al'Ālam. Translated and Explained by V. Minorsky. pp. 286, 347-348

- R. Khanam, Encyclopaedic ethnography of Middle-East and Central Asia: P-Z, Volume 3 - Page 18

- Chormaqan Noyan: The First Mongol Military Governor in the Middle East by Timothy May

- The Pearl of Pearls: The Abdālī-Durrānī Confederacy and Its Transformation under Aḥmad Shāh, Durr-i Durrān by Sajjad Nejatie. https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/80750.

- Marshall Cavendish (2006). World and Its Peoples: The Middle East, Western Asia, and Northern Africa. Marshall Cavendish. p. 320. ISBN 0-7614-7571-0:"The members of the new dynasty, although they were also Turkic, had settled in Afghanistan and brought a new set of customs and culture to Delhi."CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ashirbadi Lal Srivastava (1966). The History of India, 1000 A.D.-1707 A.D. (Second ed.). Shiva Lal Agarwala. p. 98. OCLC 575452554:"His ancestors, after having migrated from Turkistan, had lived for over 200 years in the Helmand valley and Lamghan, parts of Afghanistan called Garmasir or the hot region, and had adopted Afghan manners and customs. They were, therefore, wrongly looked upon as Afghans by the Turkish nobles in India as they had intermarried with local Afghans and adopted their customs and manners. They were looked down as non Turks by Turks."CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Abraham Eraly (2015). The Age of Wrath: A History of the Delhi Sultanate. Penguin Books. p. 126. ISBN 978-93-5118-658-8:"The prejudice of Turks was however misplaced in this case, for Khaljis were actually ethnic Turks. But they had settled in Afghanistan long before the Turkish rule was established there, and had over the centuries adopted Afghan customs and practices, intermarried with the local people, and were therefore looked down on as non-Turks by pure-bred Turks."CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Radhey Shyam Chaurasia (2002). History of medieval India: from 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. Atlantic. p. 28. ISBN 81-269-0123-3:"The Khaljis were a Turkish tribe but having been long domiciled in Afghanistan, had adopted some Afghan habits and customs. They were treated as Afghans in Delhi Court. They were regarded as barbarians. The Turkish nobles had opposed the ascent of Jalal-ud-din to the throne of Delhi."CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)