Labor policy in the Philippines

The Labor policy in the Philippines is specified mainly by the country's Labor Code of the Philippines and through other labor laws. They cover 38 million Filipinos who belong to the labor force and to some extent, as well as overseas workers. They aim to address Filipino workers’ legal rights and their limitations with regard to the hiring process, working conditions, benefits, policymaking on labor within the company, activities, and relations with employees.

The Labor Code and other legislated labor laws are implemented primarily by government agencies, namely, Department of Labor and Employment and Philippine Overseas Employment Agency. Non-government entities, such as the trade unions and employers, also play a role in the country's labor.

Labor force

The Philippines is a country that has one of the biggest available pools of qualified workers (aged 15–64) in the world in absolute terms which ranks 13th largest in the world behind countries like Vietnam, Japan, and Mexico. In 2010 its people qualified for work had reached 55.5M.[1] On its working age group's ratio to the country's total population, it ranks 147th[2] at 61%, bordering the middle and bottom third of the world ranking, by virtue of its relatively large population of elderly and children combined.

With this large pool of available workers, the Philippines has more than 38M people that belong to the labor force which is one of the largest in the world almost making it to the top ten notwithstanding a relatively mediocre participation rate of 64.5%.[3] The labor force has consistently grown by an average 2% for the past three years. This labor force is dominated by people that have an educational attainment below the tertiary level which make up 71%.[3]

Employment

Out of this labor force 36.2M[4] Filipinos are employed and this number has been increasing by an average of more than 2% in the last three years. This proportion of employed working people in the Philippines constitutes 59%[3] of the population, a relatively large percentage that belongs to the upper-third in the world ranking. The Philippines ranks relatively low in its employed worker-to-GDP ratio with only $8,260[5] which hints about the country's productivity issues. Nevertheless, this GDP per employed worker has been growing by an average of 3% over the last decade.

Most of these employed workers are in the field of Services (50%), followed by Agriculture (34%) and Industry (15%) with the lowest share.[4] There has been a considerable employment growth in each of the Services and Industry sector of about 4% since 2009 while employment in the Agricultural sector has been fluctuating. A large portion of these employed workers are salary/wage workers and then followed by self-employed.

Unemployment and under-employment

Meanwhile, there are about 2.7M Filipinos[4][6] that are unemployed which constitutes about 7.4% of the labor force. This is the lowest rate the Philippines enjoys since 1996, before the country suffered from the Asian Financial Crisis. After unemployment rate peaked in 2000,[7] it has been on a steep decline by an average of 8.5% each year through to 2010. Out of this unemployed group of workers, 88% is roughly split between people who at least had a high school or a college education.[4][6]

A large proportion of college graduates are nursing graduates whose numbers now sum up to about 200,000 according to a report by Philippine Nurses Association.[8] As of 2011, it is estimated that about 7M are underemployed . It went back up after it fell in 2010 at 6.5M. Visibly underemployed people, people working less than 40 hours per week, cover 57% while the rest is made up by Invisible underemployed people, those who work over 40 hours per week but wants more hours.[4][6]

Labor issues

Output growth and employment

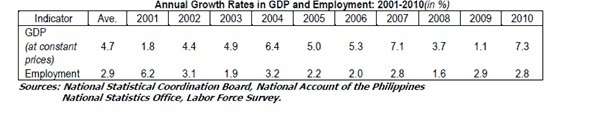

The GDP of the Philippines grew steadily from 2001 to 2004. Though there was a slowdown in 2005–2006, there was high growth again in 2006 which was interrupted only by the onset of the global financial crisis of 2008-2009.[9] During these periods of growth, there was a slower pace of growth in employment. This "lagging" may be due to the extreme weather disturbances the country experienced. Considering that a large part of the labor force is employed in agriculture, this is valid. Another reason is the difference between GDP and employment with respect to their sectoral structures. Agriculture, forestry and fishing sector contribute only less than one-fifth (16.8%) in the country's GDP in 2010 considering that one third (33.2%) of the total employed is working in this sector. This lagging could also be viewed with distinction to full-time and part-time employment. "In 2009 for instance, employment grew by 2.9% despite the slowdown in GDP to 1.1%. But the growth in employment occurred almost entirely among part-time workers (8.4%) while full-time employment actually fell (−0.5%).".[10]

Labor productivity

Total factor productivity (TFP), the efficiency in use of both labor and capital, is important because labor income depends on labor productivity growth. This growth is the average product of labor which correlates with labor's contribution to enterprise revenue and profits. Improvements in workers’ real wages and earnings is related to labor productivity growth and not exactly to employment growth. Improvements in real wages, improves the poverty incidence of the people thus helping in poverty reduction. Canlas, Aldaba, Esguerra argues that policymakers should have a good understanding of the sources of TFP because sustainable growth comes from rising TFP growth. "One key factor is educated labor, which has the capacity to invent, innovate, and master new techniques." At the long run, it is important to educate the population and invest in human development and research and development to improve TFP. But there should be care in this issue as there is the so-called job mismatch which will be discussed later. Canlas, Aldaba, Esguerra advise that to raise TFP growth, monetary policy and fiscal policy should stabilize a predictable environment for the private sector.[11]

Underemployment, overseas employment

With the declining earnings, people are looking for additional hours of work (underemployed), or going abroad (overseas employment) or choose to be self-employed. This also shows how they are not content with the quality of employment. The self-employed are actually indifferent between the wage employment and self-employment that they decided to be on their own.[11] This makes them, together with the unpaid family workers, part of the vulnerable employment and its earnings is weak compared to the wage one. On the other hand, they can be overseas Filipino workers. In 2009, it was reported that 1.423 million Filipinos were deployed overseas.[12] This mitigates the unemployment problem but also poses moral hazard problems, reducing labor force participation in the family.[11]

Youth unemployment, job and skill mismatch, educated unemployed

In 2010, half of the 2.9 million unemployed Filipinos were age 15–24.[12] More than half of the unemployed youth are stuck due to lack of job opportunities, lack of skills and the competition with older ones. This lack of training and skills and incompetence may be due to poor education, which shows that indeed, education must be improved.[11] On the other hand, there is the job and skill mismatch. Even with the high unemployment rate, there are actually jobs that are not filled because there are no applicants who have the right qualifications.[12] The improvement of education must be well-thought so that it corresponds with what the labor market needs. There must be attention given to the technical and vocational education of labor. The government should cooperate with the private sector for better information regarding the labor demand.[11] From this job mismatch problem also arises the educated unemployed. In 2010, the unemployment rate among the college educated is about 11%. Some have difficulty in finding an appropriate job for the degree they have. Others, on the other hand, have higher reservation wages and can afford to wait for better opportunities.[12]

Balance between workers' welfare and employment generation

In the past decades, the Philippines experienced that having policies that are biased on workers’ welfare and protection may hinder employment creation. Sound policies that improves the condition of employment and workers’ welfare without resulting into too much increase in labor costs would be better. The consequences of a rigid labor market due to undue intervention may result in lower investments and thus, slower growth.[11]

Labor Code of the Philippines

The Labor Code of the Philippines governs employment practices and labor relations in the Philippines. It also identifies the rules and standards regarding employment such as pre-employment policies, labor conditions, wage rate, work hours, employee benefits, termination of employees, and so on. Under the regime of the President [Ferdinand Marcos], it was promulgated in May 1. 1974 and took effect November 1, 1974, six months after its promulgation.[13]

Pre-employment policies

Minimum employable age

The minimum age for employment is 18 years old and below that age is not allowed. Persons of age 15 to 18 can be employed given that they work in non-hazardous environments.[14]

Overseas employment

As for overseas employment of Filipinos, foreign employers are not allowed to directly hire Philippine nationals except through board and entities authorized by the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration. Travel agencies also cannot transact or help in any transactions for the employment or placement of Filipino workers abroad.

Regulation on conditions of employment

Minimum wage rate

Minimum wage rates in the Philippines vary from region to region, with boards established for each region to monitor economic activity and adjust minimum wages based on growth rates, unemployment rates, and other factors.[15] The minimum wage rate for Non-Agriculture employees, in Manila region, established under Wage Order No. NCR 15 is P404 per day, but on May 9, 2011, a (cost of living allowance) of P22 per day was added to P404 wage, making the minimum wage P426. COLA was also added to the previous P367 minimum wage for the following sectors: Agriculture, Private Hospitals (with bed capacity of 100 or less), and manufacturing establishments (with less than 10 workers), leaving the sectors with P389 as minimum wage.[16] The 426 combined rate is locally referred to in the Philippines as "Manila Rate" due to this regional disparity.[15]

Regular work hours and rest periods

Normal hours of work. – The normal hours of work of any employee shall not exceed eight (8) hours a day.

Health personnel in cities and municipalities with a population of at least one million (1,000,000) or in hospitals and clinics with a bed capacity of at least one hundred (100) shall hold regular office hours for eight (8) hours a day, for five (5) days a week, exclusive of time for meals, except where the exigencies of the service require that such personnel work for six (6) days or forty-eight (48) hours, in which case, they shall be entitled to an additional compensation of at least thirty percent (30%) of their regular wage for work on the sixth day. For purposes of this Article, "health personnel" shall include resident physicians, nurses, nutritionists, dietitians, pharmacists, social workers, laboratory technicians, paramedical technicians, psychologists, midwives, attendants and all other hospital or clinic personnel.

Meal periods. – Subject to such regulations as the Secretary of Labor may prescribe, it shall be the duty of every employer to give his employees not less than sixty (60) minutes time-off for their regular meals.

Rest days

All employee have the right to have a 24 consecutive hours of rest day after every 6 days of work. Employers are responsible for determining and scheduling the rest day of employees except only if the employee prefers a different day based on religious grounds. However, the employer may require an employee to work during his/her rest day in cases of emergencies, special circumstances at work in which employees are seriously needed, to prevent losses or damage to any goods or to the employer, and other cases that have reasonable grounds.[14]

Nightshift differential and overtime

Employees are also given additional wages for working in night shifts. The night shift starts from 10 o’clock in the evening until 6 o’clock in the morning, and employees will receive 10% more of his/her regular wage rate. Overtime work for employees (beyond 8 hours) are allowed and workers shall be paid with his/her regular wage plus an additional 25% of the regular wage per hour worked or 30% during holidays or rest days.[14]

Household helpers

Household helpers, or maids, are common in the Philippines. Household helpers deliver services at the employer's home, attending to the employer's instructions and convenience. The minimum wage of household helpers is P800 per month for some cities in Metro Manila, while a lower wage is paid to those outside of Metro Manila,. However, most household helpers receive more than the minimum wage; employers usually give wages ranging from P2,500 and above per month. On top of that, employers are required to provide food, sanitary lodging, and just treatment to the household helper.[14]

Post-employment

Termination by employer

The employer has the right to terminate an employee due to the following reasons: serious misconduct or disobedience to the employer, neglect of duties or commission of a crime by the employee, and such gives the employer a just case to terminate the services of the employee.[14]

Retirement

The retirement age for an employee depends on the employment contract. Upon retirement, the retired employee should be given his/her benefits according to the agreement or contract between the employer and the employee. However, if there is no existing retirement plan or agreement for the employee, he/she may retire at the age of 60, given that he/she has served the employer for 5 years, and shall be given a retirement pay of at least half a month's salary for every year of service (6 months of work given is considered as 1 whole year for the retirement pay).[14]

Labor market institutions

Government

The Philippine government greatly affects the labor market through its policies and interventions. It plays a role in job creation through generating a formidable environment for investment; in ensuring the workers’ welfare through policies like the Labor Code; in improving the education of the labor; in informing regarding the jobs available to match the skills of the people; in implementing expansionary fiscal and monetary policies to reduce unemployment rate. Though, there must be care in using fiscal and monetary policies because it may result in high inflation rate in the long-run.[11] Below are some government agencies concerned with the labor market.

Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE)

Founded on December 8, 1933, DOLE is the government agency overseeing the labor market of the Philippines. It is tasked to implement the Labor Code and other labor and employment-related policies of the government. They have different programs for job generation, skills training for workers, job fairs and placements, for overseas workers, and others that helps enhance the labor market of the Philippines.[17]

Bureau of Labor and Employment Statistics (BLES)

Under the DOLE, BLES gathers data and research regarding the labor market. These statistics are important in making sound policies (Aldaba, Canlas,Esguerra). One example of data is that regarding job vacancies. One reason of vacancies in spite of unemployment is that people do not know where to look for the right job. BLES gather information on vacancies and applicants and submit this to DOLE for dissemination.[18]

Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA)

The Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA), under the supervision of DOLE, is the government agency mandated to oversee the development of technical education and skills development (TESD) of the labor force of the Philippines. TESDA aims to train skilled workers especially on technical and vocational services in which our country is lacking.[19]

Philippine Overseas Employment Agency (POEA)

The POEA is DOLE's arm that administers to the overseas employment of Filipino workers. It aims to ensure and protect the migrant workers' rights and welfare. It is also tasked to promote, develop and supervise the government's overseas employment program.[20]

Labor unions

Trade or Labor unions in the Philippines are organizations sanctioned by Labor Code of the Philippines as an acknowledgment of Filipino workers' freedom to self-organize. Trade unions aim to promote enlightenment among Filipino workers concerning their wages, hour of work, and other legal rights.[14] They aim to raise awareness on their obligations as union members and employees, as well. Moreover, they serve as legitimate entities that negotiate with employers in policy-making with regard to terms and conditions of employment. These negotiations formally take place in the process of Collective Bargaining Agreement.

Trade unions are granted with a right to go on a strike,[14] a temporary stoppage of work by the employees when there is a labor dispute. Labor disputes are defined as situation when there are controversies surrounding negotiations and arranging of the terms and condition of employment. The union, however, must file a notice of strike or the employer must file a notice of lockout to the Department of Labor and Employment. But when a strike or lockout is deemed to compromise national interests or interests of the Filipino public (for instance, the case of health workers), the Secretary of Labor and Employment has the authority to prohibit it and deliberately enforce resumption of regular operations.

In the Philippines, TUCP (Trade Union Congress of the Philippines) is the largest union and confederation of 30 labor federations in the country which come from a wide range of sectors.[21] As of 2009, there are a total of 34,320 unions with consist of members summing up to 2.6 million.[22]

Other labor unions in the philippines is Kilusang Mayo Uno, or May First Labor Movement.

Employers' confederation

In the Philippines, there is also an employers' confederation in order to lobby the protection of firm owners; this confederation represents the business sector and employers in the country. The most known of which is the Employers' Confederation of the Philippines. ECOP is leading in being the voice of the employers' in labor management and socioeconomic development.[23] Last September 27, 2011, ECOP had a dialogue with Labor secretary, Rosalinda Baldoz regarding different issues on labor like the Pregnant Women Workers Act, impact of too many holidays on business, wages, ongoing review of DOLE Department Order No. 18-02, and employment and competitiveness. ECOP stressed that DOLE should consider the business community when issuing policies.[24]

See also

References

- "Population ages 15–64 (% of total)". World Bank. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- "People Statistics". Nationmaster. Rapid Intelligence. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- "Labor force participation rate, total (% of total population ages 15+)". The World Bank. World Bank. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- "Labstat Updates" (PDF). Bureau of Labor and Employment Statistics. Department of Labor and Employment. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- "GDP per person employed (constant 2011 PPP $)". The World Bank. World Bank. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- "The 2014 Employment Situation" (PDF). Labstat updates. Philippine Statistics Authority. 19/1. January 2015. ISSN 0118-8747.

- "Unemployment, total (% of total labor force)". The World Bank. World Bank. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- "More and more Filipino nurses are still unemployed in the Philippines". FilipinoNursesNews.com. Retrieved September 15, 2011.

- The Philippine Labor and Employment Plan 2011–2016 (PDF) (Report). Department of Labor and Employment. April 2011. p. 3. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- The Philippine Labor and Employment Plan 2011–2016 (PDF) (Report). Department of Labor and Employment. April 2011. p. 4,5. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- Aldaba, Fernando; Canlas, Dante; Esguerra, Emmanuel. Growth, Employment Creation, and Poverty Reduction in the Philippines (Report).

- The Philippine Labor and Employment Plan 2011–2016 (PDF) (Report). Department of Labor and Employment. April 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- Jimenez, Josephus (January–December 2004). "The Philippine Labor Code's Overhaul: Its Philosophy and Scope" (PDF). UST Law Review. XLVII: 191–208. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- Philippines (1990). Labor Code of the Philippines : as amended with implementing rules and regulations. Manila: Department of Labor and Employment. Archived from the original on January 17, 2012.

- "Daily Minimum Wage Rates". National Wages and Productivity Commission. Department of Labor and Employment. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- "About DOLE". Department of Labor and Employment. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- "Brief History". Bureau of Labor and Employment Statistics. Department of Labor and Employment. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- "Mission, Vision, Value and Quality Statement". Technical Education and Skills Development Authority. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- "About POEA". POEA. Department of Labor and Employment. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- "About Us". Trade Union Congress of the Philippines. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- Crisostomo, Sheila (September 27, 2009). "362 new labor unions seek registration – DOLE". The Philippine Star. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- "About ECOP". Employers' Confederation of the Philippines. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- "ECOP Dialogue with Labor Secretary". September 27, 2011. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

External links

- Philippine Development Plan 2011–2016

- Firm Characteristics as Determinants of Views on the Minimum Wage Policy

- Job Creation: What’s Labor Policy Got to Do With It?

- Spotlighting on High Economic Growth,Employment of the Poor, and Poverty Reduction: A Three‐Pronged Strategy

- DEPARTMENT ORDER NO. 18 – 02

- Workers’ Protection in a New Employment Relationship

- Labor and Employment

- New Rules on night work