USS McCulloch (1897)

USS McCulloch, previously USRC McCulloch and USCGC McCulloch, was a ship that served as a United States Revenue Cutter Service cutter from 1897 to 1915, as a United States Coast Guard Cutter from 1915 to 1917, and as a United States Navy patrol vessel in 1917. She saw combat during the Spanish–American War during the Battle of Manila Bay and patrolled off the United States West Coast during World War I. In peacetime, she saw extensive service in the waters off the U.S. West Coast. She sank in 1917 after colliding with another steamer.

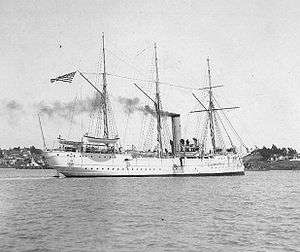

USRC McCulloch, ca. 1900. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | USRC McCulloch |

| Namesake: | Hugh McCulloch |

| Builder: | William Cramp & Sons, Philadelphia |

| Cost: | $196,500[1] |

| Yard number: | 288 |

| Launched: | 1896 |

| Commissioned: | 12 December 1897 |

| Fate: | Became part of U.S. Coast Guard fleet, 28 January 1915 |

| Name: | USCGC McCulloch |

| Namesake: | Previous name retained |

| Acquired: | 28 January 1915 |

| Fate: | Transferred to U.S. Navy, 6 April 1917 |

| Name: | USS McCulloch |

| Namesake: | Previous name retained |

| Commissioned: | 6 April 1917 |

| Fate: | Sunk in collision 13 June 1917 |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement: | 1,280[1] or 1,432 tons (sources differ) |

| Length: | 219 ft (67 m) |

| Beam: | 32 ft 6 in (9.91 m) or 33.4 ft (10.2 m)[1][2] (sources differ) |

| Draft: | 16 ft (4.9 m) |

| Depth: | 17.1 ft (5.2 m) or 19 ft (5.8 m)[2] (sources differ) |

| Propulsion: | One triple-expansion steam engine, 21½-inch-, 34½-inch-, and 56½-inch-diameter (546-mm-, 876-mm-, and 1,435-mm-diameter) x 30-inch (762-mm) stroke; 2,400 ihp (1,790 Kw); 2 boilers, 200 psi (1,379 kPa)[1][2] |

| Sail plan: |

|

| Speed: | 17 knots (on trials)[1] |

| Complement: | 130 (wartime)[1] |

| Armament: |

|

Construction and commissioning

William Cramp & Sons built McCulloch at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as a three-masted cruising cutter for the United States Revenue Cutter Service at a cost of $196,500[1] and launched her in 1896. She was of composite construction, with a hull made of wood planks mounted on a steel frame. She had a single triple-expansion steam engine and a barkentine rig that allowed her to extend her range by operating under sail power. Her four 3-inch (76 mm) guns were mounted in sponsons on her forward and aft quarters, and her single 15-inch (381 mm) torpedo tube was molded into her bow stem. At the time, she was the largest cutter ever built for the Revenue Cutter Service, and she remained the largest cutter in the Revenue Cutter Service – and later the United States Coast Guard – fleet throughout her service life.[2][3][4]

The ship was commissioned into service with the Revenue Cutter Service as USRC McCulloch on 12 December 1897. Captain D. B. Hodgsdon, USRCS, was her first commanding officer, who later commanded McCulloch at the Battle of Manila Bay.

Namesake

McCulloch was named for Hugh McCulloch (1808–1895), an American statesman who served as the 27th United States Secretary of the Treasury under Presidents Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson from 9 March 1865 to 3 March 1869 and as the 36th U.S. Secretary of the Treasury under Presidents Chester A. Arthur and Grover Cleveland from 31 October 1884 to 7 March 1885.[1] She was the third Revenue Cutter Service ship to bear the name McCulloch or Hugh McCulloch.

Operational history

Spanish–American War

As the Spanish–American War was about to commence in early 1898, McCulloch was on her shakedown cruise, a voyage from Philadelphia via the Suez Canal and the Far East to her first duty station at San Francisco, California. Upon her arrival at Singapore on 8 April 1898, two full weeks before the United States declared war on Spain, McCulloch received orders directing her to report for duty with the United States Navy′s Asiatic Squadron under the command of Commodore George Dewey.

Dewey's squadron was composed of the protected cruisers USS Olympia, USS Boston, USS Baltimore, and USS Raleigh, the gunboats USS Concord and USS Petrel, the store ships USS Nanshan and USS Zafiro, and McCulloch. The squadron stood out of Mirs Bay, China, on 27 April 1898, and entered Manila Bay off Luzon in the Philippines on the evening of 30 April 1898. By midnight Olympia had passed stealthily into the harbor. Successive ships followed in close order.

Just as McCulloch brought El Fraile Rock abaft the starboard beam, soot in her funnel caught fire and sent up a column of fire like a signal light, breaking the black stillness. Immediately thereafter, a Spanish battery on El Fraile took McCulloch under fire. Boston, in column just ahead of McCulloch, answered the battery, as did McCulloch with her starboard guns,[2] and the Spanish gun emplacement was silenced. McCulloch's chief engineer, Frank B. Randall, died of overexertion and heat exhaustion while trying to extinguish the soot fire in the funnel.[4]

As the rock fell astern, Dewey reduced speed to four knots (7.4 km/h; 4.6 mph) so as to reach the head of Manila Bay in time to join action with the Spanish Navy squadron off Cavite at daybreak on 1 May 1898. His orders required McCulloch to guard the two store ships from Spanish gunboats. She was also to protect the ships in the line of battle from surprise attack, tow any disabled ship out of range of Spanish gunfire, and take her place in the line.

In the ensuing Battle of Manila Bay, Dewey′ ships made five firing runs at close range, wreaking devastation on the Spanish squadron. MccCulloch. under fire, guarded the store ships and made ready a 9-inch (23 cm) hawser with which to assist any U.S. ship that ran aground, although that turned out to be unnecessary; at one point, in between firing passes by the U.S. squadron, she intercepted the British mail steamer Esmeralda to convey to the British steamer Dewey's orders for Esmeralda's movements in the vicinity of the battle. The battle, which began at 05:40, was over in seven hours. All of the Spanish warships were destroyed, and 381 Spanish seamen were killed. No American warship was seriously damaged, and only eight American sailors were wounded. Randall was the only American to die during the battle.[4][5]

After the battle, because of her speed, McCulloch was dispatched to the closest cable facility, that at Hong Kong, bearing the first dispatches of the great U.S. naval victory. On 17 May 1898, McCulloch left Hong Kong with Emilio Aguinaldo – the Philippine revolutionary who would later lead the Philippine forces in the Philippine–American War – aboard, arriving at Cavite in Manila Bay on 19 May.[6]

In a 12 June 1898[2] message to United States Secretary of the Navy John D. Long, Dewey commended Captain Hogsdon for the efficiency and readiness of McCulloch during the Battle of Manila Bay. Dewey presented McCulloch with four of the six 1-pounder revolving Hotchkiss guns taken from the wreck of the Spanish flagship, the cruiser Reina Cristina.[7] These four guns, each of which has five revolving 37 mm (1.5 in) barrels, are displayed in pairs to either side of the front of Hamilton Hall facing the parade ground at the United States Coast Guard Academy in New London, Connecticut.[8]

Later career

McCulloch arrived at San Francisco, California, on 10 January 1899 and operated on patrol out of that port along the United States West Coast, cruising from the Mexican border to Cape Blanco, Oregon, on law enforcement and lifesaving duties.[1][2][3] After the 1,160-gross register ton, 258.2-foot (78.7 m) steamer Cleveland was wrecked on Cape Rodney (64°39′N 165°24′W) on the west-central coast of the Territory of Alaska in a snowstorm and sank with the loss of one life on 23 October 1900, McCulloch rescued her 38 survivors from the beach.[9] McCulloch helped maintain order in the San Francisco area after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake struck on 18 April 1906.[2]

Tasked on 9 August 1906 with the enforcement of fur seal regulations, McCulloch operated in the vicinity of the Pribilof Islands until 1912. During these years of service on the Bering Sea Patrol, she was especially well known because of her services as a floating court to towns along the coast of the Territory of Alaska. Upon her return to San Francisco in 1912, McCulloch resumed patrol operations in her regular cruising district along the U.S. West Coast, with occasional deployments to Alaska. In 1914, she underwent an overhaul at Mare Island Navy Yard in Vallejo, California, in which her boilers were replaced, fuel tanks were installed, her mainmast was removed, and her bowsprit was shortened.[2][3] Her barkentine rig also was removed, and she emerged from the overhaul with two military masts instead.[1][2] On 24 November 1914, she came to the aid of the steam passenger schooner Hanalei, which had run aground on Duxbury Reef in the Pacific Ocean off California with the loss of 18 lives.[2][10]

When the Revenue Cutter Service merged with the United States Life-Saving Service on 28 January 1915 to form the United States Coast Guard, McCulloch became a United States Coast Guard Cutter as USCGC McCulloch. In January 1917, she came to the assistance of the U.S. Navy armored cruiser USS Milwaukee, which had run aground at Samoa, California, on 13 January. In March 1917, McCulloch underwent another overhaul at Mare Island in which her hull was recaulked and 800 pounds (360 kg) of copper sheathing were removed.[3]

On 6 April 1917 – the same day that the United States entered World War I – McCulloch was transferred to the U.S. Navy for wartime service as a patrol vessel, serving as USS McCulloch, the first U.S. Navy ship to bear the name. She continued patrol operations in the Pacific Ocean along the U.S. West Coast.[3]

Sinking

On 13 June 1917, McCulloch was steaming with 90 U.S. Coast Guard and U.S. Navy personnel on board from San Pedro, California, to Mare Island Navy Yard, where she was to be fitted with larger guns for her wartime Navy service. She was proceeding cautiously in heavy fog about four nautical miles (7.4 km) west-northwest of Point Conception, California, at 07:30 when her crew heard the fog signal of the Pacific Steamship Company passenger steamer Governor, which was southbound from San Francisco to San Pedro with 429 passengers and crew aboard. Governor's crew also heard McCulloch's fog signal, and Governor's captain ordered full speed astern and ordered Governor′s whistle to blow three times to indicate that her engines were at full speed astern. McCulloch was off Governor's port bow when Governor struck her on the starboard side just aft of the pilot house at 07:33, tearing a hole in McCulloch's hull and seriously injuring one of McCulloch's crewmen in his bunk. Governor, which suffered no casualties among her passengers and crew, took aboard all of McCulloch's crew, and McCulloch sank 35 minutes after the collision three nautical miles northwest of Point Conception. Her injured crewman died on 16 June 1917 in a hospital in San Pedro.[2][3]

The sinking of McCulloch was headline news across the United States because of her involvement in the Battle of Manila Bay 19 years before.[2] An inquiry into the collision found Governor at fault for disobeying the "rules of the road." Governor's owners agreed to a settlement payment of $167,500 to the United States Government in December 1923.[4]

Discovery of wreck

In October 2016, when the U.S. Coast Guard and the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) conducted a routine hydrographic survey as a joint remotely operated vehicle (ROV) training expedition off Point Conception, surveyors noted a congregation of fish – which can indicate the presence of a wreck – three nautical miles off Point Conception at a depth of 300 feet (91 m). During seven dives by a NOAA VideoRay Mission Specialist ROV operating from the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary′s research vessel RV Shearwater, researchers found a wreck at the site and took images that identified it as that of McCulloch. Key identifying features of the wreck included the 15-inch torpedo tube molded into McCulloch's bow stem, a 3-inch 6-pounder gun still mounted on its sponson on the starboard bow, and the top of a bronze 11-foot (3.4 m) propeller blade. Researchers also photographed the ship's wheel from McCulloch's flying bridge, her steam engine, and a sounding machine. White sea anemones of the genus Metridium were noted living on many portions of the wreck. The Coast Guard cutters USCGC Blacktip and USCGC Halibut supported the operations.[4][11][12][13]

On 13 June 2017 – the 100th anniversary of McCulloch's sinking – the U.S. Coast Guard held a media event to announce the discovery of the wreck. Officials also announced a decision to leave all remains of the cutter on the ocean floor because strong currents and a build-up of sediment at the wreck site and the fragility of the wreck made recovery of parts of the wreck impractical.[11][12]

In a statement marking the discovery, Rear Admiral Todd Sokalzuk, the commander of Coast Guard District 11, said:

McCulloch and her crew were fine examples of the Coast Guard's long-standing multi-mission success from a pivotal naval battle with Commodore Dewey, to safety patrols off the coast of California, to protecting fur seals in the Pribilof Islands in Alaska. The men and women who crew our newest cutters are inspired by the exploits of great ships and courageous crews like the McCulloch."[12]

Awards

References

- U.S. Coast Guard History Program: McCulloch, 1897

- sanctuaries.noaa.gov USCG McCulloch Timeline Poster

- sanctuaries.noaa.gov U.S. Coast Guard Cutter McCulloch

- sanctuaries.noaa.gov U.S. Coast Guard Cutter McCulloch

- history.navy.mil Naval Battle of Manila Bay, May 1, 1898, Ship Action Reports: U.S. Steamer 'McCulloch

- Agoncillo, Teodor A. (1990). History of the Filipino people ([8th ed.]. ed.). Quezon City: Garotech. p. 157. ISBN 978-9718711064.

- , spanamwar.com Dewey's recognition of McCulloch's efficient service.

- , 37mm guns at US Coast Guard Academy.

- alaskashipwreck.com Alaska Shipwrecks (C)

- "Casualty reports". The Times (40708). London. 26 November 1914. col E, p. 15.

- Wang, Linda (13 June 2017). "Coast Guard ship will linger in century-old watery grave". ABC News. Associated Press. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- Moore, Kirk, "Wreck of storied Coast Guard cutter McCulloch identified off California ," workboat.com, June 13, 2017.

- sanctuaries.noaa.gov U.S. Coast Guard Cutter McCulloch Factsheet

Sources

- Zolandez, Thomas (2010). "Question 29/44: Battle of Manila Bay". Warship International. XLVII (3): 218–219. ISSN 0043-0374.

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.