Mi último adiós

"Mi último adiós" (English; “My Last Farewell”) is a poem written by Filipino propagandist and writer Dr. José Rizal before his execution by firing squad on December 30, 1896. The piece was one of the last notes he wrote before his death. Another that he had written was found in his shoe, but because the text was illegible, its contents remain a mystery.

| by José Rizal | |

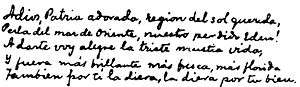

The autographed first stanza of "Mi último adiós" | |

| Written | 1896 |

|---|---|

| Country | Philippines |

| Language | Spanish |

Rizal did not ascribe a title to his poem. Mariano Ponce, his friend and fellow reformist, titled it "Mi último pensamiento" ("My Last Thought") in the copies he distributed, but this did not catch on. Also, the "coconut oil" containing the poem was not delivered to the Rizal's family until after the execution as it was required to light the cell.

Background

"On the afternoon of Dec. 29, 1896, a day before his execution, Dr. José Rizal was visited by his mother, Teodora Alonzo; sisters Lucia, Josefa, Trinidád, Maria and Narcisa; and two nephews. When they took their leave, Rizal told Trinidád in English that there was something in the small alcohol stove (cocinilla), as opposed to saying coconut oil (lamparilla), which was intended provide cover for the transportation of the text. The stove was given to Narcisa by the guard when the party was about to board their carriage in the courtyard. At home, the Rizal ladies recovered a folded paper from the stove. On it was written an unsigned, untitled and undated poem of 14 five-line stanzas. The Rizals reproduced copies of the poem and sent them to Rizal's friends in the country and abroad. In 1897, Mariano Ponce in Hong Kong had the poem printed with the title "Mí último pensamiento". Fr. Mariano Dacanay, who received a copy of the poem while a prisoner in Bilibid (jail), published it in the first issue of La Independencia on September 25, 1898 with the title 'Ultimo Adios'."[1]

Political impact

After it was annexed by the United States as a result of the Spanish–American War, the Philippines was perceived as a community of "barbarians" incapable of self-government.[2][3] U.S. Representative Henry A. Cooper, lobbying for management of Philippine affairs, recited the poem before the United States Congress. Realising the nobility of the piece's author, his fellow congressmen enacted the Philippine Bill of 1902 enabling self-government (later known as the Philippine Organic Act of 1902), despite the fact that the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act was still in effect and African Americans had yet to be granted equal rights as US citizens.[4] It created the Philippine Assembly, appointed two Filipino delegates to the American Congress, extended the US Bill of Rights to Filipinos, and laid the foundation for an autonomous government. The colony was on its way to independence. Although relatively complete autonomy would not be granted until 4 July 1946 by the Treaty of Manila.

Indonesian nationalism

The poem was translated into Bahasa Indonesia by Rosihan Anwar and was recited by Indonesian soldiers before going into battle during their struggle for independence.[5]

Anwar recalled the circumstances of the translation:

- “The situation was favorable to promote nationalism. [On 7 September 1944, Prime Minister Koiso of Japan declared that the ‘East Indies’ would become independent soon, an announcement that was received enthusiastically throughout the islands, and got ecstatic treatment in Asia Raja the following day.] In that context, I thought it would be good that I could disseminate this story about Jose Rizal among our younger people at that time. It was quite natural; I thought it would be good to tell the story of Jose Rizal, this rebel against the Spanish. And of course the climax, when he was already sentenced to death and then hauled off to face firing squad, and he wrote that [poem] ….”

- “I translated it from the English. Because I do not know Spanish. I know French, I know German, but not Spanish. Then, according to the custom at that time, everything you want to say over the radio station or anything you wanted to publish in a newspaper … everything must go first to the censorship. I sent it to [the] censor, no objection, it’s okay. Okay. Then I made an arrangement, with my friend, [an] Indonesian friend, who worked at the radio station, where everything was supposed to be supervised by the Japanese. He gave me a chance to read it, which I did …”[6]

He read "Mi último adiós" over radio in Jakarta on Saturday, 30 December 1944–Rizal’s 48th death anniversary. That same day, the paper Asia Raja devoted almost half of its back page to a feature and poem on Rizal written by Anwar, accompanied by Anwar’s translation.

Poem

| Spanish | English | Tagalog |

|---|---|---|

|

"Mi último adiós" |

"My Last Farewell" |

"Pahimakas ni Dr. José Rizal" |

Translations

"Mi último adiós" is interpreted into 46 Philippine languages, including Filipino Sign Language,[7] and as of 2005 at least 35 English translations known and published (in print). The most popular English iteration is the 1911 translation of Charles Derbyshire and is inscribed on bronze. Also on bronze at the Rizal Park in Manila, but less known, is the 1944 one of novelist Nick Joaquin. The latest translation is in Czech by former Czech ambassador to the Republic of the Philippines, H.E. Jaroslav Ludva,[8] and addressed at the session of the Senát. In 1927, Luis G. Dato translated the poem, from Spanish to English, in rhymes. Dato called it "Mí último pensamiento".[9] Dato was the first Filipino to translate the poem.[10]

Aside from those mentioned above, the poem has been translated into at least 30 other languages:

- Amharic

- Arabic

- Balinese

- Belarusian

- Bengali

- Bulgarian

- Burmese

- Catalan

- Chinese

- Croatian

- Danish

- Dutch

- Estonian

- Fijian

- Finnish

- French

- German

- Greek

- Hausa

- Hawaiian

- Hebrew

- Hindi

- Hungarian

- Igbo

- Italian

- Japanese

- Javanese

- Kannada

- Korean

- Latin

- Latvian

- Lao

- Lithuanian

- Malayalam

- Māori

- Marathi

- Norwegian

- Oromo

- Polish

- Portuguese

- Punjabi

- Romanian

- Russian[11]

- Samoan

- Sanskrit

- Sinhalese[12]

- Slovene

- Slovak

- Somali

- Swedish

- Tahitian

- Tamil

- Telugu

- Thai

- Tigrinya

- Tongan

- Turkish

- Urdu

- Ukrainian

- Vietnamese

- Wolof

- Yoruba

See also

References

- Philippine Daily Inquirer, dated 30 December 2002

- Susan Brewer (2013). "Selling Empire: American Propaganda and War in the Philippines". The Asia-Pacific Journal. 11 (40).

- Fatima Lasay (2003). "The United States Takes Up the White Man's Burden". Cleveland Heights-University Heights City School District Library. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- Pacis, Vicente Albano. "Rizal in the American Congress, December 27, 1952". The Philippines Free Press. Archived from the original on 4 May 2006. Retrieved 28 December 2005.

- "Writer's Bio: Jose Rizal". PALH Books. Archived from the original on 2011-08-28.

- Nery, John. "Column: Aquino and "the troublemaker"". Blog. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- "First Ever Filipino Sign Language Interpretation". Deaf TV Channel. 31 August 2011. Archived from the original on 2013-01-21. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- Středa, L., Zima, T. (2011). José Ritzal, osobnost historie medicíny a národní hrdina Filipín (in Czech).CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Laslo, Pablo (1934). German-English Anthology of Filipino Poets. Carriedo, Manila: Libreria Manila Filatelica. p. 22.

- Talla, Stephen Cenon Dato (2020-07-01). "Rizal's Mi Ultimo Adios English Versions". Makuapo ni Luis G. Dato. Retrieved 2020-07-10.

- "ФЭБ: Макаренко. Филиппинская литература [второй половины XIX в.]. — 1991 (текст)". feb-web.ru.

- http://www.boondi.lk/CTRLPannel/BoondiArticles.php?ArtCat=SOOK&ArtID=1533

- Mauro Garcia (1961). 'Translations of Mi Ultimo Adios,' in Historical Bulletin Manila. Philippine Historical Association.

- Hilario, Frank A (2005). indios bravos! Jose Rizal as Messiah of the Redemption. Lumos Publishing House.

- Jaroslav Ludva (2006). Mi último adiós - Poslední rozloučení. Embassy of the Czech Republic in Manila.

- Multiple Authorship (1990). Mi Ultimo Adios in Foreign and Local Translations (2 vol). National Historical Institute.

- Sung by various Artists of Spanish language as a Tribute (more information needed!)

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mi último adiós. |