Military history of the Philippines

The military history of the Philippines is characterized by wars between Philippine kingdoms and its neighbors in the precolonial era and then a period of struggle against colonial powers such as Spain and the United States, occupation by the Empire of Japan during World War II and participation in Asian conflicts post-World War II such as the Korean War and the Vietnam War. The Philippines has also battled a communist insurgency and a secessionist movement by Muslims in the southern portion of the country.

Prehistoric tribal warfares

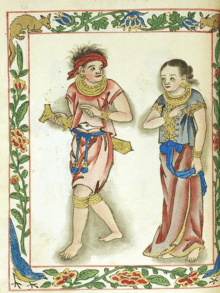

Archaeological findings dating from prehistoric eras have discovered a variety of stone and metal weaponry, such as axes, arrows and spearheads. Usually used for hunting, they also allowed tribes to battle with each other. Some more elaborate bronze pieces, such as axes and swords, were also part of the native weaponry. The making of swords involved elaborate rituals that were based mainly on the auspicious conjunctions of planets. The passage of the sword from the maker entailed a mystical ceremony that was coupled with tribal beliefs.[1] The lowlanders of Luzon use the kampilan, bararao and panabas, while the Moros and animists of the South still continue the tradition of making kris.

For example, of tribal wars are can be found at the Igorot Society, it was unified after the long clan wars between the Clans and tribes of Ifugao and Kalinga Headhunting warlords because of land resources. This unification established the culturally homogeneous society which led to the building of the Banaue Rice Terraces.[2]

Pre-colonial period (900 AD to 1565)

Champa-Sulu War

The Chams who migrated to Sulu were called Orang Dampuan.[3] [4] The Champa Civilization and the port-kingdom of Sulu engaged in commerce with each other which resulted in merchant Chams settling in Sulu where they were known as Orang Dampuan from the 10th–13th centuries. The Orang Dampuan were slaughtered by envious native Sulu Buranuns due to the wealth of the Orang Dampuan.[5] The Buranun were then subjected to retaliatory slaughter by the Orang Dampuan. Harmonious commerce between Sulu and the Orang Dampuan was later restored.[6] The Yakans were descendants of the Taguima-based Orang Dampuan who came to Sulu from Champa.[7] Sulu received civilization in its Indic form from the Orang Dampuan.[8]

Visayan Raids against China

Antecedent to this raids, sometime between A.D. 1174 and 1190, a traveling Chinese government bureaucrat Chau Ju-Kua reported that a certain group of "ferocious raiders of China's Fukien coast" which he called the "Pi-sho-ye", believed to have lived on the southern part of Formosa.[9]

In A.D. 1273, another work written by Ma Tuan Lin, which came to the knowledge of non-Chinese readers through a translation made by the Marquis D’Hervey de Saint-Denys, gave reference to the Pi-sho-ye raiders, thought to have originated from the southern portion of Formosa. However, the author observed that these raiders spoke a different language and had an entirely different appearance (presumably when compared to the inhabitants of Formosa). Some scholars have put forth the theory that the Pi-sho-ye were actually people from the Visayas islands.[9] Furthermore, Boholano oral legends say that people from the Kedatuan of Dapitan were the ones that lead the raids on China.[10]

Resistance movements by Madja-as

According to legend, the Kedatuan of Madja-as (c. 1200–1569) was founded following a civil war in collapsing Srivijaya, wherein loyalists of the Malay datus of Srivijaya defied the invading Chola dynasty and its puppet-Rajah, called Makatunao, and set up a remnant state in the islands of the Visayas. Its founding datu, Puti, had purchased land for his new realms from the aboriginal Ati hero, Marikudo.[11] Madja-as was founded on Panay island (named after the destroyed state of Pannai and settled by its descendants. Pannai was a constituent state of Srivijaya which was located in Sumatra and Pannai housed a Buddhist Monastic-Army that successfully defended the Strait of Malacca, the world's busiest maritime trading choke-point, which was surrounded by 3 most populous nations in the world then; China, India and Indonesia, yet they held the territory against all odds for 727 years). The people of Madja-as, descendants of loyalist Visayans from Pannai and Borneo who rebelled against a Chola occupation and Majapahit invasion then conducted resistance movements against the Hindu and Islamic invaders that arrived from the west from their new home-base in the Visayas islands.[12]

War between Sulu and Majapahit

In the mid 14th century, the Majapahit empire mentioned in its manuscript Nagarakretagama Canto 14, written by Prapanca in 1365, that the area of Solot (Sulu) was part of the empire.[13][14] Nagarakretagama was composed as a eulogy for their emperor Hayam Wuruk.[15] However, Chinese sources then report that in 1369, the Sulus regained independence and in vengeance, assaulted Majapahit and its province, Po-ni (Brunei), looting it of treasure and gold. A fleet from the Majapahit capital succeeded in driving away the Sulus, but Po-ni was left weaker after the attack. The Majapahit Empire, attempted to reconquer the kingdoms of Sulu and Manila but they were permanently repulsed.[16]

War between the Maguindanao and Cebu

During the early 1400s, Rajamuda Sri Lumay, a Chola dynasty prince who rebelled against the Cholas and sided with his Malay subjects established an independent Tamil-Malay Indianized kingdom in Cebu called the Rajahnate of Cebu, he established his country by waging scorched earth tactics against raiders from Mindanao mainly against the Sultanate of Maguindanao. War between Maguindanao and Cebu lasted until the Spanish era.[17]

Ming Fleet Repulsed at Luzon

The Battle of Manila in 1405 (Filipino: Labanan sa Maynila) is a battle for the whole Luzon island including Manila, which was attacked by Ming-dynasty Admiral, Zheng He who wanted to incorporate Luzon into the Ming Empire. The Chinese attacked and completely devastated Manila but they were repulsed there by an alliance of local kingdoms. They were forced to settle in Pangasinan were they made the kingdom of Caboloan a vassal-state, and a colony of the Ming dynasty.[18]

Brunei invasion of Tondo and incorporation of Sulu

The Battle of Manila (1500s) was fought in Manila between citizens of the Kingdom of Tondo led by their Lakan, Sukwu and the soldiers of the Sultanate of Brunei led by Sultan Bolkiah the singing captain. The aftermath of the battle was the formation of an alliance between the newly established Kingdom of Maynila (Selurong) and the Sultanate of Brunei, to crush the power of the Kingdom of Tondo and the subsequent installation of the Pro-Islamic Rajah Sulaiman into power. Furthermore, Sultan Bolkiah's victory over Sulu and Seludong (modern day Manila),[19] as well as his marriages to Laila Mecanai the daughter of Sulu Sultan Amir Ul-Ombra (an uncle of Sharifa Mahandun married to Nakhoda Angging or Maharaja Anddin of Sulu), and to the daughter of Datu Kemin, widened Brunei's influence in the Philippines.[20]

Territorial conflict between Manila and Tondo

According to the account of Rajah Matanda as recalled by Magellan expedition members Gines de Mafra, Rodrigo de Aganduru Moriz, and expedition scribe Antonio Pigafetta, Maynila had a territorial conflict with Tondo in the years before 1521.

At the time, Rajah Matanda's mother (whose name was not mentioned in the accounts) served as the paramount ruler of the Maynila polity, taking over from Rajah Matanda's father (also unnamed in the accounts), who had died when Rajah Matanda was still very young. Rajah Matanda, then simply known as the "Young Prince" Ache, was raised alongside his cousin, who was ruler of Tondo – presumed by some to be a young Bunao Lakandula, although not specifically named in the accounts.

During this time, Ache realized that his cousin, who was ruler of the Tondo polity, was "slyly" taking advantage of Ache's mother by taking over territory belonging to Maynila. When Ache asked his mother for permission to address the matter, his mother refused, encouraging the young prince to keep his peace instead. Prince Ache could not accept this and thus left Maynila with some of his father's trusted men, to go to his "grandfather", the Sultan of Brunei, to ask for assistance. The Sultan responded by giving Ache a position as commander of his naval force.

In 1521, Prince Ache was coming fresh from a military victory at the helm of the Bruneian navy and was supposedly on his way back to Maynila with the intent of confronting his cousin when he came upon and attacked the remnants of the Magellan expedition, then under the command of Sebastian Elcano. Some historians[21] suggest that Ache's decision to attack must have been influenced by a desire to expand his fleet even further as he made his way back to Lusong and Maynila, where he could use the size of his fleet as leverage against his cousin, the ruler of Tondo.

Battle of Mactan

The Battle of Mactan on April 27, 1521, is celebrated as the earliest reported resistance of the natives in the Philippines against western invaders. Lapu-Lapu, a Chieftain of Mactan Island, defeated Christian European explorers led by the Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan.[22][23]

On March 16, 1521, the island of Samar was sighted. The following morning, March 17, Magellan landed on the island of Homonhon.[24][25] He parleyed with Rajah Calambu of Limasawa, who guided him to Cebu Island on April 7. With the aid of Magellan's Malay interpreter, Enrique, Rajah Humabon of Cebu and his subjects converted to Christianity and became allies. Suitably impressed by Spanish firearms and artillery, Rajah Humabon suggested that Magellan project power to cow Lapu-Lapu, who was being belligerent against his authority.

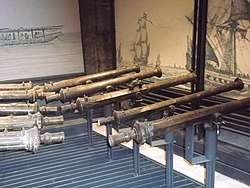

Magellan deployed 49 armored men, less than half his crew, with crossbows and guns, but could not anchor near land because the island is surrounded by shallow coral bottoms and thus unsuitable for the Spanish galleons to get close to shore. His crew had to wade through the surf to make a landing and the ship was too far to support them with artillery. Antonio Pigafetta, a supernumerary on the voyage who later returned to Seville, Spain, records that Lapu-Lapu had at least 1500 warriors in the battle. During the battle, Magellan was wounded in the leg, while still in the surf. As the crew were fleeing to the boats, Pigafetta recorded that Magellan covered their retreat, turning at them on several occasions to make sure they were getting away, and was finally surrounded by a multitude of warriors and killed. The total toll was of eight crewmen killed on Magellan's side against an unknown number of casualties from the Mactan natives.

The Kedatuan of Dapitan vs the Ternate and Lanao Sultanates

By 1563, before the full Spanish colonization agenda came to Bohol, the Kedatuan of Dapitan was at war with the Sultanate of Ternate, a Papuan speaking Muslim state in the Moluccas, which was also raiding the Rajahnate of Butuan. At the time, Dapitan was ruled by two brothers named Dalisan and Pagbuaya. The Ternateans at the time were allied to the Portuguese. Dapitan was destroyed by Ternateans and Datu Dalisan was killed in battle. His brother, Datu Pagbuaya, together with his people fled to Mindanao and established a new Dapitan in the northern coast of the Zamboanga peninsula and displaced its Muslim natives. In the process, waging war against the Sultanate of Lanao and conquering territories from the Sultanate.[10]

Lucoes Mercenary Activity

Due to the conflict-ridden nature of the Philippine archipelago, warriors were forged in the many wars in the islands, thus the islands acquired a reputation for its capable mercenaries, which were soon employed all across Southeast Asia. Lucoes (warriors from Luzon) aided the Burmese king in his invasion of Siam in 1547 AD. At the same time, Lusung warriors fought alongside the Siamese king and faced the same elephant army of the Burmese king in the defence of the Siamese capital at Ayuthaya.[26] The former sultan of Malacca decided to retake his city from the Portuguese with a fleet of ships from Lusung in 1525 AD.[lower-alpha 1]

Pinto noted that there were a number of them in the Islamic fleets that went to battle with the Portuguese in the Philippines during the 16th century. The Sultan of Aceh gave one of them (Sapetu Diraja) the task of holding Aru (northeast Sumatra) in 1540. Pinto also says one was named leader of the Malays remaining in the Moluccas Islands after the Portuguese conquest in 1511.[28] Pigafetta notes that one of them was in command of the Brunei fleet in 1521.[26] One famous Lucoes is Regimo de Raja, who was appointed by the Portuguese at Malacca as Temenggung (Jawi: تمڠݢوڠ [29]) or Supreme Governor and Chief General.

Spanish colonial period (1565–1898)

Major Revolts (1567–1872)

- Dagami Revolt (1567)

- Manila Revolt (1574)

- Conspiracy of the Maharlikas (1587–1588)

- Dingras Revolt (1589)

- Cagayan Revolt (1589)

- Magalat Revolt (1596)

- Igorot Revolt (1601)

- Irraya or Gaddang Revolt (1621)

- Sumuroy Revolt (1649–1650)

- Palaris Revolt (1762–1765)

- Cavite Mutiny (1872)

Moro campaign (1569–1898)

- Battle of Cebu (1569)

- Spanish-Moro Incident (1570)

- Jolo Jihad (1578–1580)

- Cotabato Revolt (1597)

- Spanish-Moro Incident (1602)

- Basilan Revolt (1614)

- Kudarat Revolt (1625)

- Battle of Jolo (1628)

- Sulu Revolt (1628)

- Lanao Lamitan Revolt (1637)

- Battle of Punta Flechas (1638)

- Sultan Bungsu Revolt (1638)

- Mindanao Revolt (1638)

- Lanao Revolt (1639)

- Sultan Salibansa Revolt (1639)

- Corralat Revolt (1649)

- Spanish-Moro Incident (1876)

Limahong campaign (1574–1576)

Castilian War (1578)

Cambodian-Spanish War (1593–1597)

Eighty Years' War (1568–1648)

Chinese insurrections (1603–1640)

Seven Years' War (1756–1763)

Wars in the Americas (1812–1821)

- Overseas Filipinos living in Louisiana served under Jean Lafayette in the Battle of New Orleans during the closing stages of the War of 1812.[30]

- "Manilamen" recruited from San Blas join the Argentinian of French descent, Hypolite Bouchard in the assault of Spanish California during the Argentinian War of Independence.[31][32]

- Filipinos in Mexico serving under the Filipino-Mexican General Isidoro Montes de Oca assisted Vicente Guerrero in the Mexican war of independence against Spain.[33]

Cochinchina Campaign (1858–1862)

- Siege of Đà Nẵng[34]

- Siege of Saigon (1859–1861)[34]

- Battle of Kỳ Hòa

- Capture of Biên Hòa

Taiping Rebellion (1850–1864)

- Filipinos were recruited to fight in the Ever Victorious Army against the Taiping rebels[35]

Philippine Revolution and Declaration of Independence (1896–1898)

Philippine Revolution (1896–1898)

The Philippine Revolution began in August 1896, upon the discovery of the anti-colonial secret organization Katipunan by the Spanish authorities. The Katipunan, led by Andrés Bonifacio, was a secessionist movement and shadow government spread throughout much of the islands whose goal was independence from Spain through armed revolt. In a mass gathering in Caloocan, the Katipunan leaders organized themselves into a revolutionary government and openly declared a nationwide armed revolution. Bonifacio called for a simultaneous coordinated attack on the capital Manila. This attack failed, but the surrounding provinces also rose up in revolt. In particular, rebels in Cavite led by Emilio Aguinaldo won early victories. A power struggle among the revolutionaries led to Bonifacio's execution in 1897, with command shifting to Aguinaldo who led his own revolutionary government. That year, a truce was officially reached with the Pact of Biak-na-Bato and Aguinaldo was exiled to Hong Kong, though hostilities between rebels and the Spanish government never actually ceased.[36][37]

- Battle of Alapan

- Battle of Binakayan

- Battle of Dalahican

- Battle of Julian Bridge

- Battle of San Juan del Norte

- Cry of Pugad Lawin

- Negros Revolution

Spanish–American War (1898)

The first battle in the Philippine theater was in Manila Bay, where, on May 1, 1898, Commodore George Dewey, commanding the United States Asiatic Squadron aboard the USS Olympia, in a matter of hours, defeated the Spanish squadron, under Admiral Patricio Montojo y Pasarón. Dewey's force sustaining only a single casualty — a heart attack aboard one of his vessels.

After the battle, Dewey blockaded Manila and provided transport for Emilio Aguinaldo to return to the Philippines from exile in Hong Kong. Aguinaldo arrived on May 19 and, after assuming command of Filipino forces on May 24, initiated land campaigns against the Spanish. After the Battle of Manila on the morning of August 13, 1898 (a mock battle between U.S. and Spanish forces), the Spanish governor, Fermin Jaudenes, surrendered Manila to U.S. forces under Dewey.

On June 12, 1898, with the country still under Spanish sovereignty, Aguinaldo proclaimed Philippine independence from Spain, under a dictatorial government then being established. The Act of the Declaration of Independence was prepared and written in Spanish by Ambrosio Rianzares Bautista, who read it at the proclamation ceremony. The Declaration was signed by ninety-eight persons, among them an American army officer who witnessed the proclamation. The insurgent dictatorial government was replaced on June 23 by an insurgent revolutionary government headed by Aguinaldo as president. The government included a Department of War and Public Works under which was placed the Army of Liberation of the Philippines, a volunteer army to be organized as soon as possible.[38]

The Spanish–American War was formally concluded on December 10, 1898 by the Treaty of Paris between the United States and Spain. In that treaty, Spain ceded the Philippine Archipelago to the United States, and the United States agreed to pay US$20,000,000 to the Spanish government.[39] The United States then exercised sovereignty over the Philippines. The insurgent First Philippine Republic was formally established with the proclamation of the Malolos Constitution on January 23, 1899.

American colonial period (1899–1941) and Japanese occupation (1942–1945)

Philippine–American War (1899–1913)

The Philippine–American War[lower-alpha 2] was a conflict between the United States and the First Philippine Republic from 1899 through at least 1902, when the Filipino leadership generally accepted American rule. A Philippine Constabulary organized in 1901 to deal with the remnants of the insurgent movement and gradually assumed the responsibilities of the United States Army. Skirmishes between government troops and armed groups lasted until 1913, and some historians consider these unofficial extensions part of the war.[40]

World War I (1914–1918)

In 1917 the Philippine Assembly created the Philippine National Guard with the intent to join the American Expeditionary Force. By the time it was absorbed into the National Army it had grown to 25,000 soldiers. However, these units did not see action. The first Filipino to die in World War I was Private Tomas Mateo Claudio who served with the U.S. Army as part of the American Expeditionary Forces to Europe. He died in the Battle of Chateau Thierry in France on June 29, 1918.[41][42] The Tomas Claudio Memorial College in Morong Rizal, Philippines, which was founded in 1950, was named in his honor.[43]

World War II (1939–1945)

The first Filipino military casualty during the Second World War was serving as an aviator with British forces. First Officer Isidro Juan Paredes of the Air Transport Auxiliary was killed on November 7, 1941, when his aircraft overshot a runway and crashed at RAF Burtonwood. He was buried at Great Sankey (St Mary) Churchyard Extension, but later repatriated to the Philippines.[44] Paredes Air Station in Ilocos Norte, was named in his honor.

- Battle of Agusan

- Battle of Balantang

- Battle of Balete Pass

- Battle of Bataan

- Battle of Bataan (1945)

- Battle of Batangas (1942)

- Battle of Batangas (1945)

- Battle of Bessang Pass

- Battle of Bicol Peninsula

- Battle of Bohol (1942)

- Battle of Bohol (1945)

- Battle of Bukidnon

- Battle of Cebu (1942)

- Battle of Cebu (1945)

- Battle of Corregidor

- Battle of Corregidor (1945)

- Battle of Cotabato

- Battle of Dalton Pass

- Battle of Davao

- Battle of Guila-Guila

- Battle of Ising

- Battle of Jaro

- Battle of Kirang Pass

- Battle of Lanao

- Battle of Leyte

- Battle of Leyte Gulf

- Battle of Samar (1942)

- Battle of Samar (1945)

- Battle off Samar

- Battle of Luzon

- Battle of Manila (1945)

- Battle of Maguindanao

- Battle of Marinduque

- Battle of Mayoyao Ridge

- Battle of Mindanao (1942)

- Battle of Mindanao (1945)

- Battle of Mindoro

- Battle of Misamis

- Battle of Negros

- Battle of Panay

- Battle of Romblon

- Battle of Ormoc Bay

- Battle of Simara

- Battle of Surigao

- Battle of Tayug

- Battle of the Visayas

- Battle of Zamboanga

- Bicol Campaign

- Central Luzon Campaign

- Invasion of Lingayen Gulf

- Invasion of Palawan

- Northern Luzon Campaign

- Philippines Campaign (1941–42)

- Philippines Campaign (1944–45)

- Raid at Los Baños

- Raid at Cabanatuan

- Raid at Capas

- Southern Luzon Campaign

World War II Veterans are members of the following:

- U.S. Army Forces Far East (USAFFE)

- United States Army Forces in the Philippines – Northern Luzon (USAFIP-NL)

- Philippine Scouts (PS)

- Philippine Constabulary (PC)

- Philippine Commonwealth Army (PCA) also known as the Commonwealth Army of the Philippines (CAP)

- Recognized Guerrilla Units (Philippine Commonwealth)

Related articles:

Korean War (1950–1953)

The Philippines joined the Korean War in August 1950. The Philippines sent an expeditionary force of around 7,500 combat troops. This was known as the Philippine Expeditionary Forces To Korea, or PEFTOK. It was the 4th largest force under the United Nations Command then under the command of US General Douglas MacArthur that were sent to defend South Korea from a communist invasion by North Korea which was then supported by Mao Zedong's China and the Soviet Union. The PEFTOK took part in decisive battles such as the Battle of Yultong Bridge and the Battle of Hill Eerie. This expeditionary force operated with the United States 1st Cavalry Division, 3rd Infantry Division, 25th Infantry Division, and 45th Infantry Division.[45]

- Operation Tomahawk

- Battle of Bloody Ridge

- Battle of the Imjin River

- Battle of Yultong Bridge

- Battle of Heartbreak Ridge

- Battle of Hill Eerie

Vietnam War (1964–1969)

The Philippines was involved in the Vietnam War, supporting civil and medical operations. Initial deployment in 1964 amounted to 28 military personnel, including nurses, and 6 civilians. The number of Filipino troops who served in Vietnam swelled to 182 officers and 1,882 enlisted personnel during the period 1966–1968. This force was known as the Philippine Civic Action Group-Vietnam or PHILCAG-V. Filipino troops withdrew from Vietnam on December 12, 1969.[46][47][48]

EDSA Revolution (February 22–25, 1986)

On February 22, 1986, former Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile and Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) Vice Chief of Staff and chief of the Philippine Constabulary (PC) (now the Philippine National Police) Lt. Gen. Fidel V. Ramos withdrew their support for President Ferdinand Marcos and led the EDSA Revolution by Corazon Aquino (Ninoy's widow). On February 25, 1986, Corazon Aquino was sworm in as the 11th President of the Philippines. Marcos and his family were ousted from power by a combination of the military, people and church members to end the 20-year dictatorship of Marcos.

Persian Gulf War (1990–1991)

The Philippines sent 200 medical personnel to assist coalition forces in the liberation of Kuwait from the stranglehold of Iraq then led by Saddam Hussein.

Iraq War (2003–2004)

The Philippines sent 60 medics, engineers and other troops to assist in the invasion of Iraq. The troops were withdrawn on the 14th of July, 2004, in response to the kidnapping of Angelo dela Cruz, a Filipino truck driver. When insurgent demands were met (Filipino troops out of Iraq), the hostage was released. While in Iraq, the troops were under Polish command (Central South Iraq). During that time, several Filipino soldiers were wounded in an insurgent attack, although none died.

Communist insurgent groups in the Philippines

Early 1950s to present

- Hukbalahap

- New People's Army

- National Democratic Front

Islamic insurgency in the Philippines

Late 1960s to present

- Moro National Liberation Front

- Moro Islamic Liberation Front

- Abu Sayyaf Conflict

- The Burnham Hostage Crisis

- The Maundy Thursday Rescue

- Rajah Sulaiman movement

- Maute Group (ISIS)

International Peace Support and Humanitarian Relief Operations

- UN Command in Korea (UNC), 1950–55

- Philippine Expeditionary Force to Korea (PEFTOK)

- 10th Battalion Combat Team (BCT)

- 20th BCT

- 19th BCT

- 14th BCT

- 2nd BCT

- Philippine Expeditionary Force to Korea (PEFTOK)

- UN Operation in the Congo (ONUC, or l'Operation des Nations Unies au Congo), 1963

- Philippine Air Force Contingent (PAFCON) featuring the Limbas Squadron

- ONUC Fighter Wing Commander Lieutenant Colonel Jose L Rancudo, leading pilots and air crew from Iran, the Philippines, and Sweden

- Philippine Medical Mercy Mission to Indonesia, 1963

- "More Flags"/Free World Assistance Program in Vietnam, 1964–71

- Philippine Contingent, Vietnam (PHILCONV)

- Philippine Civic Action Group, Republic of Vietnam I (First PHILCAGV)

- Philippine Civic Action Group, Republic of Vietnam (Second PHILCAGV)

- Philippine Contingent, Vietnam (PHILCAGV rear party)

- UN Guards Contingent in Iraq (UNGCI), 1991–92

- First Philippine-UN Guards Contingent in Iraq (PUNGCI-1)

- Second PUNGCI (PUNGCI-2)

- Third PUNGCI (PUNGCI-3)

- Fourth PUNGCI (PUNGCI-4)

- Fifth PUNGCI (PUNGCI-5, -5A, -5B, -5C)

- Sixth PUNGCI (PUNGCI-6A, -6B, -6C, -6D)

- Seventh PUNGCI (PUNGCI-7A, -7B)

- Eighth PUNGCI (PUNGCI-8A, -8B)

- Ninth PUNGCI (PUNGCI-9A, -9B, -9C)

- Tenth PUNGCI (PUNGCI-10A)

- UN Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC), 1992–93

- First Republic of the Philippines Contingent to UNTAC (1RP-UNTAC)

- Second RP-UNTAC (2RP-UNTAC)

- UNTAC Military Experts on Mission

- International Force East Timor (INTERFET), 1999

- Philippine Humanitarian Support for East Timor (PhilHSMET)

- UN Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET), 1999–2002

- Philippine Battalion (PhilBatt)

- UNTAET Force Headquarters Support Unit (FHSU)/Philippine Contingent to East Timor (PhilCET)

- UNTAET Peacekeeping Force Staff

- UNTAET Military Experts on Mission

- UNTAET Peacekeeping Force Supreme Commander Jaime S de los Santos, leading 8,500 personnel from 19 Troop-Contributing Countries

- Henri Dunant Centre for Humanitarian Dialogue Aceh Monitoring Movement (HAMM), 2002–03

- AFP Contingent to the HAMM International Monitoring Team

- UN Mission of Support in East Timor (UNMISET), 2002–05

- UNMISET Force Headquarters Support Unit (FHSU)/Philippine Contingent to East Timor (PhilCET)

- UNMISET Peacekeeping Force Staff

- UNMISET Military Experts on Mission

- Philippine Humanitarian Contingent to Iraq, 2003–04

- UN Mission in Liberia (UNMIL), 2003–2014

- First Philippine Contingent to Liberia (1PCL)

- Second PCL (2PCL)

- Third PCL (3PCL)

- Fourth PCL (4PCL)

- Fifth PCL (5PCL)

- Sixth PCL (6PCL)

- Seventh PCL (7PCL)

- Eighth PCL (8PCL)

- Ninth PCL (9PCL)

- Tenth PCL (10PCL)

- Eleventh PCL (11PCL)

- Twelfth PCL (12PCL)

- Thirteenth PCL (13PCL)

- Fourteenth PCL (14PCL)

- Fifteenth PCL (15PCL)

- Sixteenth PCL (16PCL)

- Seventeenth PCL (17PCL)

- Eighteenth PCL (18PCL)

- UNMIL Peacekeeping Force Staff / Military Staff Officers

- UNMIL Military Experts on Mission

- UN Mission in Côte d'Ivoire (MINUCI, or la Mission des Nations Unies en Côte d'Ivoire), 2004

- MINUCI Military Experts on Mission

- UN Operation in Côte d'Ivoire (ONUCI, or l'Operation des Nations Unies en Côte d'Ivoire), 2004–2015

- ONUCI Peacekeeping Force Staff / Military Staff Officers

- ONUCI Military Experts on Mission

- UN Mission in Burundi (ONUB, or l'Operation des Nations Unies au Burundi), 2004–06

- ONUB Military Experts on Mission

- UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH, or l'Operation des Nations Unies pour la Stabilisation en Haiti), 2004–present

- First Philippine Contingent to Haiti (1PCH)

- Second PCH (2PCH)

- Third PCH (3PCH)

- Fourth PCH (4PCH)

- Fifth PCH (5PCH)

- Sixth PCH (6PCH)

- Seventh PCH (7PCH)

- Eighth PCH (8PCH)

- Ninth PCH (9PCH)

- Tenth PCH (10PCH)

- Eleventh PCH (11PCH)

- Twelfth PCH (12PCH)

- Thirteenth PCH (13PCH)

- Fourteenth PCH (14PCH)

- Fifteenth PCH (15PCH)

- Sixteenth PCH (16PCH)

- Seventeenth PCH (17PCH)

- MINUSTAH Peacekeeping Force Staff / Military Staff Officers

- UN Office in Timor-Leste (UNOTIL), 2005–06

- UNOTIL Military Experts on Mission

- European Union Aceh Monitoring Mission, 2005–06

- AMM Peace Monitors

- UN Mission in the Sudan (UNMIS), 2005–11

- UNMIS Military Experts on Mission

- UN Integrated Mission in Timor-Leste (UNMIT), 2006–12

- UNMIT Military Experts on Mission

- Philippine Humanitarian Mission and Aid for Myanmar, 2008

- UN Military Observer Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP), 2009–present

- UNMOGIP Military Experts on Mission

- UN Disengagement Force (UNDOF) in the Golan Heights, 2009–14

- Philippine Battalion – First Philippine Contingent to the Golan Heights (1PCGH)

- Philippine Battalion – Second PCGH (2PCGH)

- Philippine Battalion – Third PCGH (3PCGH)

- Philippine Battalion – Fourth PCGH (4PCGH)

- Philippine Battalion – Fifth PCGH (5PCGH)

- Philippine Battalion – Sixth PCGH (6PCGH)

- Philippine Battalion – Seventh PCGH (7PCGH)

- UNDOF Peacekeeping Force Staff / Military Staff Officers

- UNDOF Commander and Head of Mission Major General Natalio C Ecarma III, leading 800 personnel from 10 Troop-Contributing Countries

- UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS), 2011–12

- UNMISS Military Experts on Mission

- UN Interim Security Force for Abyei (UNISFA), 2011–12

- UNISFA Military Experts on Mission

- UN Supervision Mission in Syria (UNSMIS), 2012

- UNSMIS Military Experts on Mission

List of coups d'état

- People Power Revolution

- 1986–1987 Philippine coup attempts

- 1989 Philippine coup attempt

- EDSA Revolution of 2001

- Attempted coups against Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo

- EDSA III

- Oakwood Mutiny – The Oakwood Mutiny refers to a short-lived event which occurred on 27 July 2003 when members of the Philippine Marine Corps and Army took hold of the Glorietta Mall and the Oakwood Premier Condominium in Makati City. See Oakwood Mutiny

- 2006 state of emergency in the Philippines

- Manila Peninsula Mutiny

List of treaties

- Treaty of Paris (1763) (minor role)

- Treaty of Paris (1898)

- The National Defense Act of 1935 – In 1935 The National Defense Act of 1935 was enacted. President-elect Manuel L. Quezon convinced Chief of Staff of the United States Army General Douglas MacArthur to act as the military adviser to the Commonwealth of the Philippines. MacArthur was given the title "Military Advisor to the Commonwealth Government" and tasked with establishing a system of national defense, for the Philippines, by 1946. For a time, MacArthur would also act as the Field Marshal of the Philippine Army.

- Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) (dissolved)

- Mutual Defense Treaty between the Republic of the Philippines and the United States of America (1951)

- RP-US Visiting Forces Agreement

- BALIKATAN – "Shoulder to Shoulder" Joint US-Philippines Military Exercises

- Framework Agreement on the Bangsamoro

- Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement

List of awards

- Philippine Legion of Honor

- Philippine Medal of Valor

- Philippine Distinguished Service Cross

- Asiatic Pacific Campaign Medal

- World War II Victory Medal

- Philippine Liberation Medal

- Philippine Defense Medal

- Philippine Independence Medal

- Philippine Presidential Unit Citation

List of wars involving the Philippines

- Philippine Revolution

- Spanish–American War

- Philippine–American War

- World War I

- World War II

- Japanese occupation of the Philippines

- Philippines campaign (1941–42)

- Philippines campaign (1944–45)

- Cold War

- Korean War

- Vietnam War

- Communist Insurgencies

- War on Terror

- Islamic Insurgencies

- Operation Iraqi Freedom

See also

- Armed Forces of the Philippines

- Philippine Air Force

- Philippine Navy

- Philippine Marine Corps

- Philippine Army

- Philippine Constabulary

- Military History of the Philippines During World War II

- History of the Philippines

- Presidential Security Group / Presidential Security Command

- Filipino Special Forces

- General Alfredo M. Santos – the first four-star general of the Philippine Army and the Armed Forces of the Philippines (1963)

- Philippine National Police

- Reform the Armed Forces Movement

- Reserve Officers' Training Corps (Philippines)

- Katipunan

- Philippine Revolutionary Army

- Armed Forces of the Philippines

- Military History of the Philippines

- Philippine Commonwealth Army

- Luna sharpshooter

- List of conflicts in the Philippines

- List of wars involving the Philippines

Notes

- The former sultan of Malacca decided to retake his city from the Portuguese with a fleet of ships from Lusung in 1525 AD.[27]

- This conflict is also known as the 'Philippine Insurrection'. This name was historically the most commonly used in the U.S., but Filipinos and some American historians refer to these hostilities as the Philippine–American War, and, in 1999, the U.S. Library of Congress reclassified its references to use this term.

References

- Carol R. Ember & Melvin Ember (2003). Encyclopedia of sex and gender: men and women in the world's cultures, Volume 1. Springer. p. 498. ISBN 978-0-306-47770-6.

- History of the Philippines. Chapter 3: Our Early Ancestors.

- UNDERSTANDING HISTORY.

- The Filipino Moving Onward 5' 2007 Ed. Rex Bookstore, Inc. pp. 3–. ISBN 978-971-23-4154-0.

- Philippine History Module-based Learning I' 2002 Ed. Rex Bookstore, Inc. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-971-23-3449-8.

- Philippine History. Rex Bookstore, Inc. 2004. pp. 46–. ISBN 978-971-23-3934-9.

- Study Skills in English for a Changing World' 2001 Ed. Rex Bookstore, Inc. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-971-23-3225-8.

- Jobers Bersales, Raiding China at Inquirer.net

- History of the Kingdom of Dapitan. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- G. Nye Steiger, H. Otley Beyer, Conrado Benitez, A History of the Orient, Oxford: 1929, Ginn and Company, p. 121.

- Najeeb Mitry Saleeby (1908). The History of Sulu. Ethnological Survey for Philippine Islands (Illustrated ed.). Bureau of Printing, Harvard University. pp. 152–153. OCLC 3550427. Retrieved 20 June 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- "A Complete Transcription of Majapahit Royal Manuscript of Nagarakertagama". Jejak Nusantara (in Indonesian).

- Day, Tony & Reynolds, Craig J. (2000). "Cosmologies, Truth Regimes, and the State in Southeast Asia". Modern Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 34 (1): 1–55. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00003589. JSTOR 313111.

- History for Brunei Darussalam: Sharing our Past. Curriculum Development Department, Ministry of Education. 2009. p. 44. ISBN 978-99917-2-372-3.

- Celestino C. Macachor (2011). "Searching for Kali in the Indigenous Chronicles of Jovito Abellana". Rapid Journal. 10 (2). Archived from the original on 2012-07-03.

- Globalita: "China's Colonization of the Philippines".

- History for Brunei Darussalam 2009, p. 41.

- "Brunei". CIA World Factbook. 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Jose Rizal, as cited by Dery, 2001

- Halili, M.c. (2004). Philippine history. Rex Bookstore, Inc. pp. 74. ISBN 978-971-23-3934-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ongsotto (2002). Philippine History Module-based Learning I' 2002 Ed. Rex Bookstore, Inc. pp. 63. ISBN 978-971-23-3449-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Halili 2004, p. 72

- Ongsotto 2002, p. 62

- Pigafetta, Antonio (1969) [1524]. "First voyage round the world". Translated by J. A. Robertson. Manila: Filipiniana Book Guild. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Barros, Joao de, Decada terciera de Asia de Ioano de Barros dos feitos que os Portugueses fezarao no descubrimiento dos mares e terras de Oriente [1628], Lisbon, 1777, courtesy of William Henry Scott, Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society, Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1994, page 194.

- Pinto, Fernao Mendes (1989) [1578]. "The travels of Mendes Pinto". Translated by Rebecca Catz. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Turnbull, C.M. (1977). A History of Singapore: 1819–1975. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-580354-X.

- Williams, Rudi (3 June 2005). "DoD's Personnel Chief Gives Asian-Pacific American History Lesson". American Forces Press Service. U.S. Department of Defense. Archived from the original on June 15, 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2009.

- Delgado de Cantú, Gloria M. (2006). Historia de México. México, D. F.: Pearson Educación.

- Mercene, Manila men, p. 52.

- Filipinos in Nueva España Filipino-Mexican Relations, Mestizaje, and Identity in Colonial and Contemporary Mexico by Rudy P. Guevarra Jr. "According to Ricardo Pinzon, these two Filipino soldiers—Francisco Mongoy and Isidoro Montes de Oca—were so distinguished in battle that they are regarded as folk heroes in Mexico. General Vicente Guerrero later became the first president of Mexico of African descent. See Floro L. Mercene, “Central America: Filipinos in Mexican History,” "(https://muse.jhu.edu/article/456194/pdf)

- Nigel Gooding, Filipino Involvement in the French-Spanish Campaign in Indochina, retrieved 2008-07-04

- Caleb Carr, The devil soldier: the story of Frederick Townsend Ward, New York: Random House, 1992, p. 91.

- Guererro, Milagros; Encarnacion, Emmanuel; Villegas, Ramon (1996), "Andres Bonifacio and the 1896 Revolution", Sulyap Kultura, National Commission for Culture and the Arts, 1 (2): 3–12, archived from the original on 2010-11-15.

- Guerrero 1998.

- The Philippine Army, 1935–1942. Ateneo University Press. 1992. pp. 10, 231 (note 4 attributes this title to documentary evidence consulted by Onofre D. Corpuz). ISBN 978-971-550-081-4.

- Treaty of Peace Between the United States and Spain Archived 2007-11-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Constantino, Renato (1975). The Philippines: A Past Revisited. ISBN 971-8958-00-2.

- Zena Sultana-Babao, America's Thanksgiving and the Philippines’ National Heroes Day: Two Holidays Rooted in History and Tradition, Asian Journal, archived from the original on 2009-01-11, retrieved 2008-01-12

- Source: Philippine Military Academy

- "Schools, colleges and Universities: Tomas Claudio Memorial College". Manila Bulletin Online. Archived from the original on 2007-07-07. Retrieved 2007-07-04.

- "Tomas Claudio Memorial College". www.tcmc.edu.ph. Archived from the original on 2007-06-30. Retrieved 2007-07-04. - Casualty Details: Paredes, Isidro Juan, Commonwealth War Graves Commission, retrieved 2008-01-12 His death was registered at the Maidenhead Register of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, where his nationality is recorded as "United Kingdom".

- Art Villasanta, The Philippines in the Korean War, archived from the original on October 22, 2009, retrieved 2008-07-04

- http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/philippine-soldiers-depart-south-vietnam

- Fidel V. Ramos (August 1, 2008), A brotherhood FORGED IN HARDSHIP, asianbiztimes.com, archived from the original on October 6, 2011, retrieved 2009-01-04

- historynet.com, The Philippines: Allies During The Vietnam War, retrieved 2008-07-04

- Balao, Colonel Dante D and Annanette B Cruz-Salazar. Global Kawal. Quezon City, The Philippines: Armed Forces of the Philippines. 2008. ISBN 978-971-92556-3-5

- Ancan, Colonel Roberto T and Annanette B Cruz. Global Kawal: The Filipino Soldier in the United Nations Blue Beret (Second Edition). Quezon City, The Philippines: Armed Forces of the Philippines. 2015. ISBN 978-971-92556-4-2

- Alejandrino, Charlemagne S and Annanette B Cruz-Salazar. National Pride, World Peace. City of Pasig, The Philippines: Makabayan Publishing House. 2010. ISBN 978-971-94613-0-2

External links

- Philippine Presidential Security Group

- AFP Armaments Upgrade Forum

- Armed Forces of the Philippines Forum

- Comparative Analysis of the Use of Foreign Military Sales (FMS) and Direct Commercial Sales (DCS) in the Procurement of US Defense Articles by the Philippine Government for the Use of the Armed Forces of the Philippines

- Philippine Peacekeepers: Instruments of World Peace, Sources of National Pride