Simón Bolívar

Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios Ponte-Andrade y Blanco[1] (24 July 1783 – 17 December 1830), generally known as Simón Bolívar (Spanish: [siˈmom boˈliβaɾ] (![]()

Simón Bolívar | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st President of Gran Colombia | |

| In office 24 February 1819 – 4 May 1830 | |

| Vice President | Francisco de Paula Santander |

| Preceded by | Office Established |

| Succeeded by | Domingo Caycedo |

| 1st President of Bolivia | |

| In office 12 August 1825 – 29 December 1825 | |

| Preceded by | Office Established |

| Succeeded by | Antonio José de Sucre |

| 6th President of Peru | |

| In office 10 February 1824 – 28 January 1827 | |

| Preceded by | José Bernardo de Tagle, Marquis of Torre-Tagle |

| Succeeded by | Andrés de Santa Cruz |

| President of the Third Republic of Venezuela | |

| In office October 1817 – 24 February 1819 | |

| Preceded by | Himself |

| Succeeded by | José Antonio Páez (President of Venezuela) |

| President of the Second Republic of Venezuela | |

| In office 1813 – 16 July 1814 | |

| Preceded by | Francisco de Miranda (As President of the First Republic of Venezuela) |

| Succeeded by | Himself |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 24 July 1783 Caracas, Captaincy General of Venezuela (Kingdom of Venezuela), Spanish Empire |

| Died | 17 December 1830 (aged 47) Santa Marta, Gran Colombia (now in Colombia) |

| Cause of death | Tuberculosis |

| Nationality | Spanish (until 1810) Colombian (1810-1830) Venezuelan (1813-1819) |

| Spouse(s) | María Teresa Rodríguez del Toro y Alaiza |

| Domestic partner | Doña Manuela Sáenz y Aizpuru |

| Signature |  |

Bolívar was born into a wealthy family and as was common for the heirs of upper-class families in his day, was sent to be educated abroad at a young age, arriving in Spain when he was 16 and later moving to France. While in Europe he was introduced to the ideas of the Enlightenment, which later motivated him to overthrow the reigning Spanish in colonial South America. Taking advantage of the disorder in Spain prompted by the Peninsular War, Bolívar began his campaign for independence in 1808.[5] The campaign for the independence of New Granada was consolidated with the victory at the Battle of Boyacá on 7 August 1819. He established an organized national congress within three years. Despite a number of hindrances, including the arrival of an unprecedentedly large Spanish expeditionary force, the revolutionaries eventually prevailed, culminating in the patriot victory at the Battle of Carabobo in 1821, which effectively made Venezuela an independent country.

Following this triumph over the Spanish monarchy, Bolívar participated in the foundation of the first union of independent nations in Latin America, Gran Colombia, of which he was president from 1819 to 1830. Through further military campaigns, he ousted Spanish rulers from Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, the last of which was named after him. He was simultaneously president of Gran Colombia (present-day Venezuela, Colombia, Panama and Ecuador), Peru, and Bolivia, but soon after, his second-in-command, Antonio José de Sucre, was appointed president of Bolivia. Bolívar aimed at a strong and united Spanish America able to cope not only with the threats emanating from Spain and the European Holy Alliance but also with the emerging power of the United States. At the peak of his power, Bolívar ruled over a vast territory from the Argentine border to the Caribbean Sea.

Bolívar fought 100 battles, of which 79 were important ones, and during his campaigns rode on horseback 70,000 kilometers, which is 10 times more than Hannibal, three times more than Napoleon, and twice as much as Alexander the Great.[6] Bolívar is viewed as a national icon in much of modern South America, and is considered one of the great heroes of the Hispanic independence movements of the early 19th century, along with José Miguel Carrera, José de San Martín, Francisco de Miranda and others. Towards the end of his life, Bolívar despaired of the situation in his native region, with the famous quote "all who served the revolution have plowed the sea".[7]:450 In an address to the Constituent Congress of the Republic of Colombia, Bolívar stated "Fellow citizens! I blush to say this: Independence is the only benefit we have acquired, to the detriment of all the rest."[8]

Family history

Origin of Bolívar surname

The surname Bolívar originated with aristocrats from La Puebla de Bolívar, a small village in the Basque Country of Spain.[9] Bolívar's father came from the female line of the Ardanza family.[10][11] His maternal grandmother was descended from families from the Canary Islands.[lower-alpha 2]

16th century

The Bolívars settled in Venezuela in the 16th century. Bolívar's first South American ancestor was Simón de Bolívar (or Simon de Bolibar; the spelling was not standardized until the 19th century), who lived and worked from 1559 to 1560 in Santo Domingo (present-day Dominican Republic) where his son Simón de Bolívar y Castro was born. When the governor was reassigned to Venezuela by the Spanish Crown in 1569, Simón de Bolívar went with him. As an early settler in Spain's Venezuela Province he became prominent in the local society, and he and his descendants were granted estates, encomiendas, and positions in the local cabildo.[12]

When Caracas Cathedral was built in 1569, the Bolívar family had one of the first dedicated side chapels. The majority of the wealth of Simón de Bolívar's descendants came from their estates. The most important was a sugar plantation with an encomienda that provided the labor needed to run the estate.[13] Another portion of the Bolívars' wealth came from silver, gold, and copper mines. Small gold deposits were first mined in Venezuela in 1669, leading to the discovery of much more extensive copper deposits. From his mother's side (the Palacios family), Bolívar inherited the Aroa copper mines at Cocorote. Native American and African slaves provided the majority of the labor in these mines.[14]

17th century

Toward the end of the 17th century, copper mining became so prominent in Venezuela that the metal became known as cobre Caracas ("Caracas copper"). Many of the mines became the property of the Bolívar family. Bolívar's grandfather, Juan de Bolívar y Martínez de Villegas, paid 22,000 ducats to the monastery at Santa Maria de Montserrat in 1728 for a title of nobility that had been granted by King Philip V of Spain for its maintenance. The crown never issued the patent of nobility, and so the purchase became the subject of lawsuits that were still in progress during Bolívar's lifetime, when independence from Spain made the point moot. (If the lawsuits had been successful, Bolívar's older brother, Juan Vicente, would have become the Marquess of San Luis and Viscount of Cocorote.) Bolívar ultimately devoted his personal fortune to the revolution. Having been one of the wealthiest persons within the Spanish American world at the beginning of the revolution, he died in poverty.[7]

Early life

Childhood

Simón Bolívar was born in a house in Caracas, Captaincy General of Venezuela, on 24 July 1783.[7]:6 He was baptized as Simón José Antonio de la Santísima Trinidad Bolívar y Palacios. His mother was María de la Concepción Palacios y Blanco, and his father was Colonel Don Juan Vicente Bolívar y Ponte. He had two older sisters and a brother: María Antonia, Juana, and Juan Vicente. Another sister, María del Carmen, died at birth.[1]

When Bolívar was an infant, he was cared for by Doña Ines Manceba de Miyares and the family's slave, Hipólita. A couple of years later, he returned to the care of his parents, but this experience would have a major effect on his life. His father died before Bolívar's third birthday to tuberculosis,[1] and his mother died when he was almost nine.

After his mother's death, Bolívar was placed in the custody of an instructor, Miguel José Sanz, but this relationship did not work out and he was sent back home. He went on to receive private lessons from the renowned professors Andrés Bello, Guillermo Pelgrón, Jose Antonio Negrete, Fernando Vides, Father Andújar, and Don Simón Rodríguez, formerly known as Simón Carreño. Don Simón Rodríguez became Bolívar's teacher, friend and mentor. He taught him how to swim and ride horses, as well as about liberty, human rights, politics, history, and sociology.[15] Later in life, Rodríguez was pivotal in Bolívar's decision to start the revolution, instilling in him the ideas of liberty, enlightenment, and freedom.[15] In the meantime, Bolívar was mostly cared for by his nurse, the slave Hipólita, whom he later called "the only mother I have known".[16]

Youth

When Bolívar was fourteen, Don Simón Rodríguez was forced to leave the country after being accused of involvement in a conspiracy against the Spanish government in Caracas. Bolívar then entered the military academy of the Milicias de Aragua.[15] In 1800, he was sent to Spain to follow his military studies in Madrid, where he remained until 1802. Back in Europe in 1804, he lived in France and traveled to different countries. While in Milan, Bolívar witnessed the coronation of Napoleon as King of Italy (a kingdom in personal union with France in modern northern Italy), an event that left a profound impression on him. Even if he disagreed with the crowning, he was highly sensitive to the popular veneration inspired by the hero.[15]

Political and military career

Venezuela and New Granada, 1807–1821

Prelude, 1807–1810

Bolívar returned to Venezuela in 1807. After a coup on 19 April 1810, Venezuela achieved de facto independence when the Supreme Junta of Caracas was established and the colonial administrators deposed. The Supreme Junta sent a delegation to Great Britain to get British recognition and aid. This delegation presided by Bolívar also included two future Venezuelan notables Andrés Bello and Luis López Méndez. The trio met with Francisco de Miranda and persuaded him to return to his native land.

First Republic of Venezuela, 1811–1812

In 1811, a delegation from the Supreme Junta, also including Bolívar, and a crowd of commoners enthusiastically received Miranda in La Guaira.[17] During the insurgence war conducted by Miranda, Bolívar was promoted to colonel and was made commandant of Puerto Cabello the following year, 1812. As Royalist Frigate Captain Domingo de Monteverde was advancing into republican territory from the west, Bolívar lost control of San Felipe Castle along with its ammunition stores on 30 June 1812. Bolívar then retreated to his estate in San Mateo.

Miranda saw the republican cause as lost and signed a capitulation agreement with Monteverde on 25 July, an action that Bolívar and other revolutionary officers deemed treasonous. In one of Bolívar's most morally dubious acts, he and others arrested Miranda and handed him over to the Spanish Royal Army at the port of La Guaira.[18] For his apparent services to the Royalist cause, Monteverde granted Bolívar a passport, and Bolívar left for Curaçao on 27 August.[19] It must be said, though, that Bolívar protested to the Spanish authorities about the reasons why he handled Miranda, insisting that he was not lending a service to the Crown but punishing a defector. In 1813, he was given a military command in Tunja, New Granada (modern-day Colombia), under the direction of the Congress of United Provinces of New Granada, which had formed out of the juntas established in 1810.

Second Republic of Venezuela (1813–1814) and exile

This was the beginning of the Admirable Campaign. On 24 May, Bolívar entered Mérida, where he was proclaimed El Libertador ("The Liberator").[20] This was followed by the occupation of Trujillo on 9 June. Six days later, and as a result of Spanish massacres on independence supporters, Bolívar dictated his famous "Decree of War to the Death", allowing the killing of any Spaniard not actively supporting independence. Caracas was retaken on 6 August 1813, and Bolívar was ratified as El Libertador, establishing the Second Republic of Venezuela. The following year, because of the rebellion of José Tomás Boves and the fall of the republic, Bolívar returned to New Granada, where he commanded a force for the United Provinces.

His forces entered Bogotá in 1814 and recaptured the city from the dissenting republican forces of Cundinamarca. Bolívar intended to march into Cartagena and enlist the aid of local forces in order to capture the Royalist town of Santa Marta. In 1815, however, after a number of political and military disputes with the government of Cartagena, Bolívar fled to Jamaica, where he was denied support. After an assassination attempt in Jamaica,[21] he fled to Haiti, where he was granted protection. He befriended Alexandre Pétion, the president of the recently independent southern republic (as opposed to the Kingdom of Haiti in the north), and petitioned him for aid.[20] He provided the South American leader with a multitude of provisions consisting of ships, men and weapons; only demanding in return that Bolívar promise to abolish slavery in any of the lands he took back from Spain. The pledge would indeed be upheld, and the abolition of slavery in the liberated territories would be regarded as one Bolívar's main achievements.[22]

Campaigns in Venezuela, 1816–1818

In 1816, with Haitian soldiers and vital material support, Bolívar landed in Venezuela and fulfilled his promise to Pétion to free Spanish America's slaves on 2 June 1816.[7]:186

The Expedition of the Keys was led by Bolivar and fought for Venezuela in the east, while the Guyana Campaign started in the west and was led by Manuel Piar.

In July 1817, on a second expedition, he captured Angostura after defeating the counter-attack of Miguel de la Torre.[7]:192–201 However, Venezuela remained a captaincy of Spain after the victory in 1818 by Pablo Morillo in the Second Battle of La Puerta (es).[7]:212

After capturing Angostura, and an unexpected victory in New Granada, Bolivar set up a temporary government in Venezuela. This was the start of the Third Republic of Venezuela. With this Bolivar created the Congress of Angostura which following the wars would establish Gran Colombia, a state which includes today's territories of Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, and Venezuela.

To honor Bolivar's efforts to help Venezuela during its independence movement, the city of Angostura was renamed to Ciudad Bolivar in 1846.

Liberation of New Granada and Venezuela, 1819–1821

On 15 February 1819, Bolívar was able to open the Venezuelan Second National Congress in Angostura, in which he was elected president and Francisco Antonio Zea was elected vice president.[7]:222–25 Bolívar then decided that he would first fight for the independence of New Granada, to gain resources of the viceroyalty, intending later to consolidate the independence of Venezuela.[25]

The campaign for the independence of New Granada, which included the crossing of the Andes mountain range, one of history's great military feats, was consolidated with the victory at the Battle of Boyacá on 7 August 1819.[7]:233 Bolívar returned to Angostura, when congress passed a law forming a greater Republic of Colombia on 17 December, making Bolívar president and Zea vice president, with Francisco de Paula Santander vice president on the New Granada side, and Juan Germán Roscio vice president on the Venezuela side.[7]:246–47

Morillo was left in control of Caracas and the coastal highlands.[7]:248 After the restoration of the Cádiz Constitution, Morillo ratified two treaties with Bolívar on 25 November 1820, calling for a six-month armistice and recognizing Bolívar as president of the republic.[7]:254–55 Bolívar and Morillo met in San Fernando de Apure on 27 November, after which Morillo left Venezuela for Spain, leaving La Torre in command.[7]:255–57

From his newly consolidated base of power, Bolívar launched outright independence campaigns in Venezuela and Ecuador. These campaigns concluded with the victory at the Battle of Carabobo, after which Bolívar triumphantly entered Caracas on 29 June 1821.[7]:267 On 7 September 1821, Gran Colombia (a state covering much of modern Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, and Venezuela) was created, with Bolívar as president and Santander as vice president.

Ecuador and Peru, 1822–1825

Bolívar followed with the Battle of Bombona and the Battle of Pichincha, after which he entered Quito on 16 June 1822.[7]:287 On 26 and 27 July 1822, Bolívar held the Guayaquil Conference with the Argentine General José de San Martín, who had received the title of "Protector of Peruvian Freedom" in August 1821 after partially liberating Peru from the Spanish.[7]:295 Thereafter, Bolívar took over the task of fully liberating Peru.

The Peruvian congress named him dictator of Peru on 10 February 1824, which allowed Bolívar to reorganize completely the political and military administration. Assisted by Antonio José de Sucre, Bolívar decisively defeated the Spanish cavalry at the Battle of Junín on 6 August 1824. Sucre destroyed the still numerically superior remnants of the Spanish forces at Ayacucho on 9 December 1824.

According to British historian Robert Harvey:

Bolívar's achievements in Peru had been as staggering as any in his career of a year, from holding a strip of the country's north coast while himself nearly moribund, he and Sucre had taken on and defeated an army of 18,000 men and secured a country the size of nearly all of Western Europe...the investment of personal energy, the distances covered and the four army expeditions across supposedly impassable mountain ranges had qualified him for superhuman status...His stamina and military achievements put him at the forefront of the global heroes of history.[26]

Writing to United States Secretary of State John Quincy Adams in 1824, United States Consul in Peru William Tudor stated:

Unfortunately for Peru, the invaders who came to proclaim liberty and independence were cruel, rapacious, unprincipled and incapable. Their mismanagement, their profligacy, and their thirst for plunder soon alienated the affections of the inhabitants.[27]

Even though Bolívar condemned the corrupt practices of the Spanish, he ordered some churches stripped of their decorations.[28] On 19 March 1824, José Gabriel Pérez wrote to Antonio José de Sucre about the orders given to him by Bolívar;[29] Pérez talked about "all the ordinary and extraordinary means" that should be applied to assure the subsistence of the patriot army. Indeed, Pérez said that Bolívar issued instructions to take from churches "all golden and silver jewels" in order to coin them and pay war expenditures. Days later, Bolívar himself said to Sucre that there would be a complete lack of resources unless severe actions were taken against "the jewels of the churches, everywhere".[30]

Consolidation of independence, 1825–1830

Republic of Bolivia

On 6 August 1825, at the Congress of Upper Peru, the "Republic of Bolivia" was created.[7]:346 Bolívar is thus one of the few people to have a country named after him. Bolívar returned to Caracas on 12 January 1827, and then back to Bogotá.[7]:369, 378, 408

Bolívar had great difficulties maintaining control of the vast Gran Colombia. In 1826, internal divisions sparked dissent throughout the nation, and regional uprisings erupted in Venezuela. The new South American union had revealed its fragility and appeared to be on the verge of collapse. To preserve the union, an amnesty was declared and an arrangement was reached with the Venezuelan rebels, but this increased the political dissent in neighboring New Granada. In an attempt to keep the nation together as a single entity, Bolívar called for a constitutional convention at Ocaña in March 1828.[31]

Struggles inside Gran Colombia

_1860_000.jpg)

Bolívar thought that a federation like the one founded in the United States was unworkable in the Spanish America.[7]:106, 166 For this reason, and to prevent a break-up, Bolívar sought to implement a more centralist model of government in Gran Colombia, including some or all of the elements of the Bolivian constitution he had written, which included a lifetime presidency with the ability to select a successor (although this presidency was to be held in check by an intricate system of balances).[7]:351

This move was considered controversial in New Granada and was one of the reasons for the deliberations, which met from 9 April to 10 June 1828. The convention almost ended up drafting a document which would have implemented a radically federalist form of government, which would have greatly reduced the powers of a central administration. The federalist faction was able to command a majority for the draft of a new constitution which has definite federal characteristics despite its ostensibly centralist outline. Unhappy with what would be the ensuing result, pro-Bolívar delegates withdrew from the convention, leaving it moribund.[32]

Two months after the failure of this congress to write a new constitution, Bolívar was declared president-liberator in Colombia's "Organic Decree".[7]:394 He considered this a temporary measure, as a means to reestablish his authority and save the republic, although it increased dissatisfaction and anger among his political opponents.[7]:408 An assassination attempt on 25 September 1828 failed (in Spanish it is indeed known as the Noche Septembrina), thanks to the help of his lover, Manuela Sáenz.[7]:399–405 Bolívar afterward described Manuela as "Liberatrix of the Liberator".[7]:403 Dissent continued, and uprisings occurred in New Granada, Venezuela, and Ecuador during the next two years.[32]

Bolivar initially tried to forgive those who were considered conspirators, members of the "Santander" faction. Eventually it was decided to submit them to martial justice, after which those accused of being directly involved were executed, some without having their guilt fully established. Santander, who had known in advance of the conspiracy and had not directly opposed it because of his differences with Bolivar, was condemned to death. Bolivar, though, commuted the sentence.

After the facts, Bolivar continued to govern in a rarefied environment, cornered by fractional disputes. Uprisings occurred in New Granada, Venezuela, and Ecuador during the following two years. The separatists accused him of betraying republican principles and of wanting to establish a permanent dictatorship.[32] Gran Colombia declared war against Peru when president General La Mar invaded Guayaquil. He was later defeated by Marshall Antonio José de Sucre in the Battle of the Portete de Tarqui, 27 February 1829. Sucre was killed on 4 June 1830.[33] General Juan José Flores wanted to separate the southern departments (Quito, Guayaquil, and Azuay), known as the District of Ecuador, from Gran Colombia to form an independent country and become its first President. Venezuela was proclaimed independent on 13 January 1830 and José Antonio Páez maintained the presidency of that country, banishing Bolivar.

Dissolution of Gran Colombia

For Bolívar, Hispanic America was the fatherland. He dreamed of a united Spanish America and in the pursuit of that purpose he not only created Gran Colombia but also the Confederation of the Andes whose aim was to unite the aforementioned with Peru and Bolivia. Moreover, he promoted a network of treaties keeping the newly liberated South American countries together. Nonetheless, he was unable to control the centrifugal process which pushed outwards in all directions.

On 20 January 1830, as his dream fell apart, Bolívar delivered his final address to the nation, announcing that he would be stepping down from the presidency of Gran Colombia. In his speech, a distraught Bolívar urged the people to maintain the union and to be wary of the intentions of those who advocated for separation. (At the time, "Colombians" referred to the people of Gran Colombia (Venezuela, New Granada, and Ecuador), not modern-day Colombia):

Bogotá, 20 January 1830.

Simón Bolívar

Colombians! Today I cease to govern you. I have served you for twenty years as soldier and leader. During this long period we have taken back our country, liberated three republics, fomented many civil wars, and four times I have returned to the people their omnipotence, convening personally four constitutional congresses. These services were inspired by your virtues, your courage, and your patriotism; mine is the great privilege of having governed you.

The constitutional congress convened on this day is charged by Providence with the task of giving the nation the institutions she desires, following the course of circumstances and the nature of things.

Fearing that I may be regarded as an obstacle to establishing the Republic on the true base of its happiness, I personally have cast myself down from the supreme position of leadership to which your generosity had elevated me.

Colombians! I have been the victim of ignominious suspicions, with no possible way to defend the purity of my principles. The same persons who aspire to the supreme command have conspired to tear your hearts from me, attributing to me their own motives, making me seem to be the instigator of projects they themselves have conceived, representing me, finally, as aspiring to a crown which they themselves have offered on more than one occasion and which I have rejected with the indignation of the fiercest republican. Never, never, I swear to you, has it crossed my mind to aspire to a kingship that my enemies have fabricated in order to ruin me in your regard.

Do not be deceived, Colombians! My only desire has been to contribute to your freedom and to be the preservation of your peace of mind. If for this I am held guilty, I deserve your censure more than any man. Do not listen, I beg you, to the vile slander and the tawdry envy stirring up discord on all sides. Will you allow yourself to be deceived by the false accusations of my detractors? Please don't be foolish!

Colombians! Gather around the constitutional congress. It represents the wisdom of the nation, the legitimate hope of the people, and the final point of reunion of the patriots. Its sovereign decrees will determine our lives, the happiness of the Republic, and the glory of Colombia. If dire circumstances should cause you to abandon it, there will be no health for the country, and you will drown in the ocean of anarchy, leaving as your children's legacy nothing but crime, blood, and death.

Fellow Countrymen! Hear my final plea as I end my political career; in the name of Colombia I ask you, beg you, to remain united, lest you become the assassins of the country and your own executioners.

Bolívar[34]

Bolívar ultimately failed in his attempt to prevent the collapse of the union. Gran Colombia was dissolved later that year and was replaced by the republics of Venezuela, New Granada, and Ecuador. Ironically, these countries were established as centralist nations, and would be governed for decades this way by leaders who, during Bolívar's last years, had accused him of betraying republican principles and of wanting to establish a permanent dictatorship. These separatists, among them José Antonio Páez and Francisco de Paula Santander, had justified their opposition to Bolívar for this reason and publicly denounced him as a monarch. Some of them had in the past been accused of plotting against Bolívar's life (Santander, who governed the second centralist government of New Granada, was associated with the September Conspiracy).

José María Obando, the first President of the Republic of New Granada (that succeeded the Gran Colombia), had been directly linked to the assassination of Antonio José de Sucre in 1830. Sucre was regarded by some as a political threat because of his popularity after he led a resounding patriot victory at the Battle of Ayacucho, ending the war against the Spanish Empire in South America. Bolívar also considered him his direct successor and had attempted to make him vice president of Gran Colombia after Francisco de Paula Santander was exiled in 1828.[35]

Aftermath

For the rest of the 19th century and into the early 20th century, the political environment of Latin America was fraught with civil wars and characterized by a sociopolitical phenomenon known as caudillismo, which became very common in Venezuela, especially after 1830.[36]

Indeed, such struggles already existed shortly after the patriot victory over the loyalists because the former Spanish colonies created new nations that proclaimed their own autonomous states, which produced military confrontations with political conspirations that sent some of the former independence heroes into exile.[37] Moreover, there were attempts by the Spanish monarchy to reconquer their former settlements in the Americas through expeditions that would help the remaining loyalist forces and advocates. However, the attempts generally failed in Venezuela, Perú and Mexico; thus, the loyalist resistance forces against the republic were finally defeated.[38]

The main characteristic of caudillismo was the arrival of authoritarian but charismatic political figures who would typically rise to power in an unconventional way, often legitimizing their right to govern through undemocratic processes. These caudillos maintained their control primarily on the basis of their personalities, as well as skewed interpretations of their popularity and what constituted a majority among the masses. On his deathbed, Bolívar envisaged the emergence of countless caudillos competing for the pieces of the great nation he once dreamed about.

Final months and death

Saying that "all who served the revolution have plowed the sea",[7]:450 Bolívar finally resigned the presidency on 27 April 1830, intending to leave the country for exile in Europe.[7]:435 He had already sent several crates containing his belongings and writings ahead of him to Europe,[39] but he died before setting sail from Cartagena.

It is said that before Simón Bolívar had passed away, he had declared that "America is ungovernable." Bolívar was a man who had seen the negative in things. This negativity had grown from the distances that had separated the large continent or from the differences in the cultures, languages, ethnicities and the races of the people. Another factor could have been from the lack of political unity, but it is unclear what had led him to being pessimistic. These factors had caused Bolívar to put his hope on hold of uniting the sovereign territory. Old colonial cities had been separated and new trading centers had been separated by great geographical features such as mountains, high deserts and arid plains. These were all factors in which played a role and were responsible for the broken states during a time where wars of independence had risen.[40]

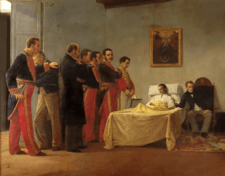

On 17 December 1830, at the age of 47, Simón Bolívar died of tuberculosis[41] in the Quinta de San Pedro Alejandrino in Santa Marta, Gran Colombia (now Colombia). On his deathbed, Bolívar asked his aide-de-camp, General Daniel F. O'Leary, to burn the remaining extensive archive of his writings, letters, and speeches. O'Leary disobeyed the order and his writings survived, providing historians with a wealth of information about Bolívar's liberal philosophy and thought, as well as details of his personal life, such as his long love affair with Manuela Sáenz. Shortly before her own death in 1856, Sáenz augmented this collection by giving O'Leary her own letters from Bolívar.[39]

Bolívar's remains were buried in the cathedral of Santa Marta. Twelve years later, in 1842, at the request of President José Antonio Páez, they were moved from Santa Marta to Caracas, where they were buried in the cathedral of Caracas together with the remains of his wife and parents. In 1876, he was moved to a monument set up for his interment at the National Pantheon of Venezuela. The Quinta near Santa Marta has been preserved as a museum with numerous references to his life. In 2010, symbolic remains of Bolívar's later-years lover, Manuela Sáenz, were also interred in Venezuela's National Pantheon.[42]

In January 2008, then-President of Venezuela Hugo Chávez set up a commission[43] to investigate theories that Bolívar was the victim of an assassination. On several occasions, Chávez has claimed that Bolívar was in fact poisoned by "New Granada traitors".[44] In April 2010, infectious diseases specialist Paul Auwaerter studied records of Bolívar's symptoms and concluded that he might have suffered from chronic arsenic poisoning, but that both acute poisoning and murder were unlikely.[45][46] In July 2010, Bolívar's body was ordered to be exhumed to advance the investigations.[47] In July 2011, international forensics experts released their report, claiming there was no proof of poisoning or any other unnatural cause of death.[48]

Private life

Marriage

In 1799, following the early deaths of his father Juan Vicente (dead since 1786) and his mother Concepción (who died in 1792), Bolívar traveled to Mexico, France, and Spain, at the age of 16 years, to complete his education. While in Madrid during 1802 and after a two-year courtship, he married María Teresa Rodríguez del Toro y Alaiza, who was to be his only wife. She was related to the aristocratic families of the marquis del Toro of Caracas and the marquis de Inicio of Madrid.[15]

Eight months after returning to Venezuela with him, she died from yellow fever on 22 January 1803. Bolívar was so devastated by this loss that his relatives feared for his life. He swore never to marry again, a promise he kept. Many years later Bolívar would refer to the death of his wife as the turning point of his life. Indeed, in 1828, he told Luis Perú de Lacroix the following words:

You then [...] got married at the age of 45; [...] I was not even 18 years old when I did the same, and I was not even nearly 19 years old when I was widowed; I loved my wife dearly, and her death made me swear not to get married again, and I kept my word. Look the way things are: if I were not widowed, my life would have maybe been different; I would not be the General Bolívar nor the Libertador, though I agree that my temper is not suitable for being the landlord of San Mateo.[49]

Not surprisingly, Spanish historian Salvador de Madariaga refers to the death of Bolivar's wife as one of the key moments in Hispanic America's history.[50] In 1804, he traveled again to Europe in an attempt to ease his pain and began falling into a dissolute life. It was then that he met again with his old teacher Simón Rodríguez in Paris, who little by little was able to transform his acute depression into a sense of commitment towards a greater cause: the independence of Venezuela. He lived in Napoleonic France for a while and undertook the Grand Tour.[51] During this time in Europe, Bolívar met the intellectual explorer, Alexander von Humboldt in Rome. Humboldt later wrote: "I was wrong back then, when I judged him a puerile man, incapable of realizing so grand an ambition."[7]:64

Affairs and lovers

Bolívar had several love affairs. Most of them were ephemeral and did not last long. Historians, scholars and biographers often agree with the names of the most prominent women who stood with Bolívar, such as Josefina "Pepita" Machado, Fanny du Villars and Manuela Sáenz.

Manuela Sáenz was the most important of those women. She was more than a lover in Bolívar's later life; she became a trustworthy confidant and advisor. Moreover, Manuela saved Bolívar's life during the September Conspiracy of 1828 in which Bolívar was about to be killed. During this assassination attempt, Manuela diverted the assassins and thus gave Bolívar enough time to escape from his room.[52]

Bolívar and Manuela met in Quito on 22 June 1822 and they began a long-term affair. The relationship was controversial at the time, because Manuela was already married to James Thorne, but they became estranged in 1822 due to irreconcilable differences.[53] The emotional ties between Manuela and Bolívar were strong, and Manuela attempted suicide when she received the news of Bolívar's death.

Despite sometimes living in the same South American cities (such as Bogotá, Quito and Lima), Bolívar and Manuela did not always have a face-to-face relationship. This romance was clear in their letters, but few of them have survived. Most of her letters were destroyed after Manuela's death.[54][55] Contrary to the arguments exposed by Heinz Dieterich, Carlos Álvarez Saá, and a book edited by Fundación Editorial El Perro y la Rana publishing house in 2007, several letters attributed to both Bolívar and Manuela are intentional forgeries.[56]

Descriptions of Bolívar

Ducoudray Holstein

In his Memoirs of Simón Bolívar, Henri La Fayette Villaume Ducoudray Holstein (who himself has been called a "not-always-reliable and never impartial witness"[57]) described the young Bolívar as he was attempting to seize power in Venezuela and New Granada in 1814–1816. Ducoudray Holstein joined Bolívar and served on his staff as an officer during this period.

He describes Bolívar as a coward who repeatedly abandoned his military commission in front of the enemy, and also as a great lover of women, being accompanied at all times by two or more of his mistresses during the military operations. He would not hesitate to stop the fleet transporting the whole army and bound for Margarita Island during two days in order to wait for his mistress to join his ship. According to Ducoudray Holstein, Bolívar behaved essentially as an opportunist preferring intrigues and secret manipulation to an open fight. He was also deemed incompetent in military matters, systematically avoiding any risks and permanently anxious for his own safety.

In the Diario de Bucaramanga, Bolívar's opinion of Ducoudray is presented when Louis Peru de Lacroix asked who had been Bolívar's aides-de-camp since he had been general; he mentioned Charles Eloi Demarquet and Ducoudray. Bolívar confirmed the first but denied the second, saying that he had met him in 1815 and accepted his services, even admitting him to his General Staff, but "I never trusted him enough to make him my aide-de-camp; to the contrary, I had a very unfavorable idea of his person and his services", and that Ducoudray's departure after only a brief stay had been a "real pleasure."[58]

Relatives

Bolívar had no children, possibly because of infertility caused by having contracted measles and mumps as a child. His closest living relatives descend from his sisters and brother. One of his sisters died in infancy. His sister Juana Bolívar y Palacios married their maternal uncle, Dionisio Palacios y Blanco, and had two children, Guillermo and Benigna. Guillermo Palacios died fighting alongside his uncle Simón in the battle of La Hogaza on 2 December 1817. Benigna had two marriages, the first to Pedro Briceño Méndez and the second to Pedro Amestoy.[59] Their great-grandchildren, Bolívar's closest living relatives, Pedro, and Eduardo Mendoza Goiticoa lived in Caracas as of 2009.

His eldest sister, María Antonia, married Pablo Clemente Francia and had four children: Josefa, Anacleto, Valentina, and Pablo. María Antonia became Bolívar's agent to deal with his properties while he served as president of Gran Colombia and she was an executrix of his will. She retired to Bolívar's estate in Macarao, which she inherited from him.[60]

His older brother, Juan Vicente, who died in 1811 on a diplomatic mission to the United States, had three children born out of wedlock whom he recognized: Juan, Fernando Simón, and Felicia Bolívar Tinoco. Bolívar provided for the children and their mother after his brother's death. Bolívar was especially close to Fernando and in 1822 sent him to study in the United States, where he attended the University of Virginia. In his long life, Fernando had minor participation in some of the major political events of Venezuelan history and also traveled and lived extensively throughout Europe. He had three children, Benjamín Bolívar Gauthier, Santiago Hernández Bolívar, and Claudio Bolívar Taraja. Fernando died in 1898 at the age of 88.[61]

Bolivar's Personal Beliefs

Politics

Simón Bolívar was an admirer of both the U.S. and French Revolutions.[7]:35, 52–53 Bolívar even enrolled his nephew, Fernando Bolívar, in a private school in Philadelphia, Germantown Academy, and paid for his education, including attendance at Thomas Jefferson's University of Virginia.[7]:71–72, 369 While he was an admirer of U.S. independence, he did not believe that its governmental system could work in Latin America.[62] Thus, he claimed that the governance of heterogeneous societies like Venezuela "will require a firm hand".[63]

Bolívar felt that the U.S. had been established in land especially fertile for democracy. By contrast, he referred to Spanish America as having been subject to the "triple yoke of ignorance, tyranny, and vice".[7]:224 If a republic could be established in such a land, in his mind, it would have to make some concessions in terms of liberty. This is shown when Bolívar blamed the fall of the first republic on his subordinates trying to imitate "some ethereal republic" and in the process, not paying attention to the gritty political reality of South America.[64]

Among the books accompanying him as he traveled were Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations, Voltaire's Letters and, when he was writing the Bolivian constitution, Montesquieu's The Spirit of the Laws.[65] His Bolivian constitution placed him within the camp of what would become Latin American conservatism in the later nineteenth century. The Bolivian constitution intended to establish a lifelong presidency and a hereditary senate, essentially recreating the British unwritten constitution, as it existed at the time.

According to Carlos Fuentes:

How to govern ourselves after winning independence. It can be said that the Liberator exhausted his soul trying to find an answer to that question...Bolívar tried to avoid the extremes that would overwhelm Spanish America all along the nineteenth century and part of the twentieth. Tyranny or anarchy? 'Do not aim at what is impossible to attain, because in the quest for liberty we may fall into tyranny. Absolute liberty always leads to absolute power and among these two extremes is social liberty'. In order to find this equilibrium, Bolívar proposed a 'clever despotism', a strong executive power able to impose equality there where racial inequality prevailed. Bolívar warned against an 'aristocracy of rank, employment and fortune' that while 'referring to liberty and guarantee' it would just be for themselves but not for levelling with members of lower classes'...He is the disciple of Montesquieu in his insistence that institutions have to be adapted to culture.

— El Espejo Enterrado, México, Fondo de Cultura Económica (1992), p. 272

Freemasonry

Similarly to some others in the history of American Independence (George Washington, Miguel Hidalgo, José de San Martín, Bernardo O'Higgins, Francisco de Paula Santander, Antonio Nariño, and Francisco de Miranda), Simón Bolívar was a Freemason. He was initiated in 1803 in the Masonic Lodge Lautaro, which operated in Cádiz, Spain,.[66][67] It was in this lodge that he first met some of his revolutionary peers, such as José de San Martín. In May 1806 he was conferred the rank of Master Mason in the "Scottish Mother of St. Alexander of Scotland" in Paris. During his time in London, he frequented "The Great American Reunion" lodge in London, founded by Francisco de Miranda. In April 1824, Simón Bolívar was given the 33rd degree of Inspector General Honorary.[68]

He founded the Masonic Lodge No. 2 of Peru, named "Order and Liberty".[69][70]

Legacy

Political legacy

Due to the historical relevance of Bolívar as a key element during the process of independence in Hispanic America, his memory has been strongly attached to sentiments of nationalism and patriotism, being a recurrent theme of rhetoric in politics. Since the image of Bolívar became an important part to the national identities of Venezuela, Colombia, Panama, Ecuador, Peru and Bolivia, his mantle is often claimed by Hispanic American politicians all across the political spectrum.

In Venezuela, Bolívar left behind a militarist legacy[71] with multiple governments utilizing the memory, image and written legacy of Bolívar as important parts of their political messages and propaganda.[72] Bolívar disapproved of the excesses of "party spirit" and "factions", which led to an anti-political environment in Venezuela.[73] For much of the 1800s, Venezuela was ruled by caudillos, with six rebellions occurring to take control of Venezuela between 1892 and 1900 alone.[73] The militarist legacy was then used by the nationalist dictatorship of Marcos Pérez Jiménez[72] and more recently the socialist political movement led by Hugo Chávez.[74]

Monuments and physical legacy

The nations of Bolivia and the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, and their respective currencies (the Bolivian boliviano and the Venezuelan bolívar), are all named after Bolívar. Additionally, most cities and towns in Colombia and Venezuela are built around a main square known as Plaza Bolívar, as is the case with Bogotá.[75] In this example, most governmental buildings and public structures are located on or around the plaza, including the National Capitol and the Palace of Justice. Besides Quito and Caracas, there are monuments to Bolívar in the Latin American capitals of Lima,[76] Buenos Aires,[77] Havana,[78] Mexico City,[79] Panama City,[80] Paramaribo,[81] San José,[82] Santo Domingo[83] and Sucre.[84] In Bogotá, the Simón Bolívar Park has hosted many concerts.[85]

Outside of Latin America, the variety of monuments to Simón Bolívar are a continuing testament to his legacy. These include statues in many capitals around the world, including Algiers,[86] Ankara, Bucharest,[87] London,[88] Minsk,[89] Moscow,[90] New Delhi,[91] Ottawa,[92] Paris,[93] Prague,[94] Port-au-Prince,[95] Rome,[96] Sofia,[97] Tehran,[98] Vienna[99] and Washington, D.C..[100] Several cities in Spain, especially in the Basque Country, have constructed monuments to Bolívar, including a large monument in Bilbao[101] and a comprehensive Venezuelan government-funded museum in Cenarruza-Puebla de Bolívar,[102] his ancestral hometown. In the US, an imposing bronze equestrian statue of Simón Bolívar stands at the southern entrance to Central Park at the Avenue of the Americas in New York City which also celebrates Bolívar's contributions to Latin America.[103] The Bolivar Peninsula in Texas, Bolivar County, Mississippi, Bolivar, New York, Bolivar, West Virginia and Bolivar, Tennessee are also named in his honor.

Monuments to Bolívar's military legacy also comprise one of Venezuelan Navy's sail training barques, which is named after him, and the USS Simon Bolivar, a Benjamin Franklin-class fleet ballistic missile submarine which served with the U.S. Navy between 1965 and 1995.

Minor planet 712 Boliviana discovered by Max Wolf is named in his honor. The name was suggested by Camille Flammarion.[104] The first Venezuelan satellite, Venesat-1, was given the alternative name Simón Bolívar after him.

His birthday is a public holiday in Venezuela and Bolivia.

- Monuments

Simón Bolívar Memorial Monument, standing in Santa Marta (Colombia) at the Quinta de San Pedro Alejandrino

Simón Bolívar Memorial Monument, standing in Santa Marta (Colombia) at the Quinta de San Pedro Alejandrino Statue of Bolívar in Plaza Bolívar in Caracas by Adamo Tadolini

Statue of Bolívar in Plaza Bolívar in Caracas by Adamo Tadolini Simón Bolívar's statue in Paris

Simón Bolívar's statue in Paris Statue of Simón Bolívar in Lisbon, Portugal.

Statue of Simón Bolívar in Lisbon, Portugal._01.jpg) Statue of Simón Bolívar in Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain.

Statue of Simón Bolívar in Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain.

In popular culture

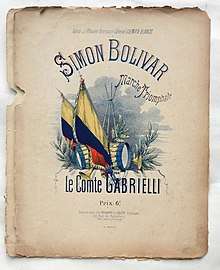

Bolívar has been depicted in opera, literature, film, and other media, and continues to be a part of the popular culture in many countries. In 1883, to celebrate 100 years since his birth, the Italian musician Nicolò Gabrielli composed the triumphal march Simón Bolívar and dedicated it to then president of Venezuela Antonio Guzmán Blanco. In 1943 Darius Milhaud composed the opera Bolívar. He is also the central character in Gabriel García Márquez's 1989 novel The General in His Labyrinth, in which he is portrayed in a less heroic but more humane manner than in most other parts of his legacy. In 1969 Maximilian Schell played the role of Simón Bolívar in the film of the same name by director Alessandro Blasetti, which also featured actress Rosanna Schiaffino. Bolívar's life was also the basis of the 2013 film Libertador, starring Édgar Ramírez and directed by Alberto Arvelo. In an episode of the Spanish TV series The Ministry of Time, "Tiempo de ilustrados (Time of the Enlightened)", the time agents help him win the heart of his future wife, as this was considered fundamental for Bolívar to fulfil his destiny. Later in the second season of the series the time agents will find him again in 1828 (two years before his death) to avoid his murder, planned by Santander's followers. As of 2019, a Netflix series has been released depicting Bolívar's life and the major events surrounding it. The Netflix series is a Colombian production with Spanish as the main language.

Simón Bolívar leads Gran Colombia in the video game Civilization VI. Gran Colombia was added to the game as part of the New Frontier Pass.[105]

See also

- Bolivarian Revolution

- Bolivarianism

- General Louis Peru de Lacroix, a biographer of Bolívar who served as one of his generals

- The General in His Labyrinth (1989) by Gabriel García Márquez, a fictionalized account of Bolívar's last days

- Toussaint Louverture

- Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla

- Francisco de Miranda

- José de San Martín

- Alexandre Pétion

- Statue of Simón Bolívar (Houston)

Notes

- In isolation, Simón is pronounced as Spanish [siˈmon], and that is the pronunciation in the recording.

- "Por las venas del libertador corría sangre guanche, en efecto, su abuela materna, doña Francisca Blanco de Herrera, descendía de san martines, era nieta de Juana Gutiérrez, de "nación guanche", y procedía además de otras familias canarias establecidas en Venezuela, tales como las de Blanco, Ponte, Herrera, Saavedra, Peraza, Ascanio y Guerra" ("Through the Liberator's veins ran Guanche blood. In fact his maternal grandmother, Francisca Blanco de Herrera, was a descendant of the original Canarian people, as she was the granddaughter of Juana Gutiérrez, of "the Guanche nation", and also came from other Canarian families established in Venezuela, such as Blanco, Ponte, Herrera, Saavedra, Peraza, Ascanio and Guerra. "). Hernández García, Julio: Book "Canarias – América: El orgullo de ser canario en América" (Canarias – America: The pride of being a Canario in America). First edition, 1989. Historia Popular de Canarias (Popular History of the Canary Islands).

References

- Arismendi Posada 1983, p. 9.

- "Bolívar". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "Bolivar, Simon". Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English. Longman. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- El Libertador: Writings of Simón Bolívar, ed. David Bushnell. New York: Oxford University Press 2003.

- ed, Thomas Riggs (2013). The literature of propaganda. Detroit [u.a.]: St. James Press. pp. 153–55. ISBN 978-1-55862-859-5.

- Toro Hardy, Alfredo, Understanding Latin America (2017), World Scientific, New Jersey, p. 47

- Arana, M., 2013, Bolivar, New York: Simon & Schuster, ISBN 978-1-4391-1019-5

- quoted in Jeremy Adelman, "Independence in Latin America" in The Oxford Handbook of Latin American History, José C. Moya, ed. New York: Oxford University Press 2011, p. 153.

- Museo Simon Bolivar, Cenarruza-Puebla de Bolívar, Spain.

- "Simón Bolívar". geneall.net.

- "LatinAmericanHistory.about.com". LatinAmericanHistory.about.com. 14 February 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- Slatta & de Grummond 2003, pp. 10–11.

- Masur 1969, pp. 21–22.

- Thornton 1998, p. 277.

- Arismendi Posada 1983, p. 10.

- Lynch 2007, p. 16.

- Crow (1992:431).

- Masur (1969), 98–102; and Lynch, Bolívar: A Life, 60–63.

- "Octagon Museum – Curaçao Art".

- Bushnell, David. The Liberator, Simón Bolívar. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1970. Print.

- Simón Bolívar has been indirectly saved by his French friend Benoît Chassériau who 10 December 1815 a few hours before the assassination attempt, visited him and gave him money to seek alternative accommodation. Thus, the Liberator left the room where José Antonio Páez had slept for several nights and depended on the guesthouse Rafael Pisce at the corner of Prince and White streets. The same night, Pio the servant of Bolivar and Paez plunged his murderous knife into the neck of Captain Felix Amestoy, thinking it was the Liberator. References: 1) in ‘Bolívar y los emigrados patriotas en el Caribe (Trinidad, Curazao, San Thomas, Jamaica, Haití)’ – By Paul Verna – Edition INCE, 1983; 2) in ‘Simón Bolívar: Ensayo de interpretación biográfica a través de sus documentos’ – By Tomás Polanco Alcántara – Edition Academia Nacional de la Historia, 1994. p. 505; 3) in ‘Petión y Bolívar: una etapa decisiva en la emancipación de Hispanoamérica, 1790–1830’ – Colección Bicentenario – By Paul Verna – Ediciones de la Presidencia de la República, 1980. pp. 131–34) in ‘L'ami des Colombiens, Benoît Chassériau (1780–1844)’ by Jean-Baptiste Nouvion, Patrick Puigmal (postface), LAC Editions, Paris, 2018. pp. 70–73. (ISBN 978-2-9565297-0-5

- Meade, Teresa (2016). A History of Modern Latin America 1800 To The Present. John Wiley & Sons, inc. p. 78.

- Robert, Pascal, ed. (1982). "U.S. Owes Haitian Gratitude, Not Abuse". The Crisis. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- Allen, Alexander, ed. (9 July 2013). "The Importance of Haiti". Huffington Post. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- Batallas de Venezuela: 1810–1824. p. 124. Edgar Esteves González

- Romantic Revolutionary; Simón Bolívar and the Struggle for Independence in Latin America (2011), London, Constable, pp. 318-319

- Quiroz, Alfonso W. (2008). Corrupt Circles: A History of Unbound Graft in Peru (1 ed.). Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press. pp. 88–91. ISBN 978-0-8018-9128-1.

- Rumazo González (2006), p. 151.

- Letter from José Gabriel Pérez to Antonio José de Sucre. Trujillo, 19 March 1824. Archivo del Libertador, Document 9135. Archived 14 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Letter from Simón Bolívar to Antonio José de Sucre. Trujillo, 21 March 1824. Archivo del Libertador, Document 9151. Archived 14 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Petre 1910, p. 381–82.

- Bushnell, David (1954) The Santander Regime in Gran Colombia

- Monroy, Ramón Rocha (5 June 2009). "Ultimas cartas de Sucre" (in Spanish). Bolpress. Archived from the original on 13 July 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- Fornoff, Frederick. El Libertador: Writings of Simon Bolivar. Oxford University Press, 2003, p. 143. "Writings of Simon Bolivar"

- Harvey, Robert. "Bolivar: The Liberator of Latin America". Skyhorse, 2013, Ch. 24 "Bolivar: The Liberator of Latin America"

- Cardoza Sáez, Ebert (2015). "El caudillismo y militarismo en Venezuela. Orígenes, conceptualización y consecuencias". Procesos Históricos (28). ISSN 1690-4818.

- "Triunfo de la Independencia". pares.mcu.es (in Spanish). 4 December 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "Resistencias e intentos de reconquista". pares.mcu.es (in Spanish). 4 December 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- Bolívar, Simón (1983). Hope of the universe (print ed.). Paris: UNESCO.

- Meade, Teresa (2016). A History of Modern Latin America 1800 To The Present. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 84.

- Arismendi Posada 1983, p. 19.

- BBC, Grant & 5 July 2010.

- Forero, Juan (23 February 2008). "Chávez, Assailed on Many Fronts, Is Riveted by 19th-Century Idol". The Washington Post. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- "Bolivar and Chavez a Worthy Comparison". Council on Hemispheric Affairs. 11 August 2011. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- "Doctors Reconsider Health and Death of 'El Libertador,' General Who Freed South America". Science Daily. 29 April 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- Allen, Nick (7 May 2010). "Simon Bolivar died of arsenic poisoning". The Telegraph. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- James, Ian (16 July 2010). "Venezuela opens Bolivar's tomb to examine remains". MSNBC. Archived from the original on 20 July 2010. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- Gupta, Girish (26 July 2011). "Venezuela unable to determine cause of Bolivar's death. And that's how the story ends". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- Lacroix (2009), p. 73.

- de Madariaga, Salvador (1959). Bolívar (in Spanish) (3.ª ed.). Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana. OCLC 803116575.

- Lynch 2006.

- Lecuna, Vicente (1951). Selected Writings of Bolívar. New York: The Colonial Press Inc. p. 707.

- Masur (1948), pp. 430–33.

- Hagen, Victor W. von (1952). The Four Seasons of Manuela. A Biography. The Love Story of Manuela Sáenz and Simón Bolívar. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce. pp. 302.

- Rumazo González (2007), p. 237.

- Lovera De-Sola, R.J. (2 July 2011). "Manuelita Sáenz Apócrifa". www.arteenlared.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- Slatta, Richard W. Simón Bolívar's Quest for Glory. Texas A&M University Press, 2003. Print.

- Peru de Lacroix, Luis (2009). Diario de Bucaramanga (PDF) (print ed.). Caracas: Ministry of Popular Power for Communication and Information. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 15 August 2014.

- De-Sola Ricardo, Irma, "Bolívar Palacios, Juana" in Diccionario de Historia de Venezuela, Vol. 1. Caracas: Fundación Polar, 1999. ISBN 978-980-6397-37-8 also reproduced in Simón Bolívar.org, Biografías Familiares de Simón Bolívar Archived 8 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine at Simón Bolívar, el hombre.

- De-Sola Ricardo, Irma, "Bolívar Palacios, María Antonia" in Diccionario de Historia de Venezuela, Vol. 1. [reproduced] "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 March 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2005.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link).

- Fuentes Carvallo, Rafael, "Bolívar, Fernando Simón" in Diccionario de Historia de Venezuela, Vol. 1. reproduced in Archived 4 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- Bushnell & Langley 2008.

- Bushnell & Langley 2008, p. 100.

- Bushnell & Langley 2008, p. 136.

- Lynch 2006, p. 33.

- Martinez, Carlos Antonio Jr. "Simon Bolivar, Liberator & Freemason". Masons of California. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- "Famous Freemasons in the course of history". Unmerged Lodge St. John's No. 11 F.A.A.M., Washington D.C. Archived from the original on 16 November 2015.

- Goldschein, Robert Johnson, Eric. "The Most Powerful Freemasons Ever". Business Insider. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- "List of notable freemasons". Archived from the original on 26 September 2018.

- "17 Of The Most Influential Freemasons Ever". businessinsider.com. 20 March 2014. Archived from the original on 22 November 2015. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- Uzcategui, Rafael (2012). Venezuela: Revolution as Spectacle. See Sharp Press. pp. 142–49. ISBN 978-1-937276-16-4.

- Carrera Damas, Germán (2006). Mitos políticos en las sociedades andinas: Orígenes, invenciones, ficciones. Miranda: Equinoccio. p. 398. ISBN 978-980-237-241-6.

- Block, Elena (2015). Political Communication and Leadership: Mimetisation, Hugo Chavez and the Construction of Power and Identity. Routledge. pp. 74–91. ISBN 978-1-317-43957-8.

- Martin, Stephen (5 October 2009). "Hugo Chavez presents Simon Bolivar". VenezuelAnalysis. Retrieved 9 April 2012. Halvorssen, Thor (25 July 2010). "Behind exhumation of Simon Bolivar is Hugo Chávez's warped obsession". The Washington Post.

- Solar, Igor I. (6 May 2013). "History and tragedy at Bolívar Square in Bogotá, Colombia". www.digitaljournal.com. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- Pino, David (10 October 2010). "El Monumento a Simón Bolívar". Lima la Única. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Equestrian statue of Simon Bolivar in Buenos Aires Argentina". Equestrian statues. 3 November 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Statue of Simón Bolívar | Havana, Cuba Attractions". www.lonelyplanet.com. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- Dixon, Seth (12 August 2010). "Making Mexico More "Latin": National Identity, Statuary and Heritage in Mexico City's Monument to Independence". Journal of Latin American Geography. 9 (2): 119–138. doi:10.1353/lag.2010.0005. ISSN 1548-5811.

- "Simón Bolívar Monument in Casco Viejo, Panama City, Panama". Encircle Photos. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- Suriname. "Suriname - Paramaribo". www.suriname.nu (in Dutch). Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Monument Zu Simon Bolivar In San Jose, Costa Rica Redaktionelles Foto - Bild von ernstlich, hauptsächlich: 67414231". de.dreamstime.com (in German). Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- Hora, Diario La. "Simón Bolívar, un sueño cumplido - La Hora". La Hora Noticias de Ecuador, sus provincias y el mundo (in Spanish). Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Simon Bolivar Monument In Casa De Libertad, Sucre Editorial Stock Photo - Image of building, bolivar: 109958888". www.dreamstime.com. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "10 Events You Can't Miss While Working in Colombia". Bogotá Business English. 27 September 2017. Archived from the original on 18 February 2019. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Alger - Bab El Oued - Buste de Simon Bolivar - Algérie". Routard.com (in French). Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Ambasada Venezuelei la Bucureşti aduce onoruri Eliberatorului Simón Bolívar şi oferă un discurs despre Venezuela ca punte de legătură între Alba şi Mercosur". Ambasada Republicii Bolivariene Venezuela în România. 17 December 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Simon Bolivar statue". London Remembers. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Mir Castle As Gift And Bust Of Bolivar - 5 Highlights Of Venezuela President's Visit To Belarus". BelarusFeed. 6 October 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- Press statement following Russian-Venezuelan talks // Kremlin.ru. 2010. 15 october

- "Newest square in Delhi honours revolutionary Simon Bolivar". The Hindu. 20 April 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Simon Bolivar - Ottawa, Ontario - Statues of Historic Figures on Waymarking.com". www.waymarking.com. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Au Cours la Reine, des statues glorifiant des personnages illustres : Simon Bolivar, le Marquis de La Fayette, Albert 1er des Belges". Histoires de Paris (in French). 24 July 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Simón Bolívar, Interbrigade square, Prague, Czech Republic - Statues of Historic Figures on Waymarking.com". www.waymarking.com. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- Clammer, Paul (2012). Haiti. Chalfont St Peter and Guilford, CN: Bradt Travel Guides. p. 120. ISBN 9781841624150.

- "Equestrian statue of Simon Bolivar in Rome Italy". Equestrian statues. 6 April 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Venezuela Opens Monument of Simon Bolivar in Bulgaria's Sofia - Novinite.com - Sofia News Agency". www.novinite.com. 19 April 2010. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Statue of Venezuela's founding father unveiled in Tehran in presence of Chavez". Payvand. 28 November 2004. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- "Simon Bolivar, der Befreier. Denkmal im Donaupark". meinbezirk.at (in German). 24 September 2015. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "National Mall and Memorial Parks---American Latino Heritage: A Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "El Monumento De Simon Bolivar En La Plaza Venezuela En Bilbao, España Foto de archivo - Imagen de configuración, día: 122645546". es.dreamstime.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Ziortza-Bolibar, el origen de Simón Bolívar - Ziortza-Bolibar, el pueblo en el que se forjo el inicio de la historia del "Libertador de las Américas"". Turismo País Vasco (in Spanish). 29 December 2016. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Central Park Monuments – Simon Bolivar Monument : NYC Parks". Nycgovparks.org. Retrieved 5 February 2014.

- "(712) Boliviana". (712) Boliviana In: Dictionary of Minor Planet Names. Springer. 2003. p. 69. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-29925-7_713. ISBN 978-3-540-29925-7.

- "Civilization VI - First Look: Gran Colombia | Civilization VI - New Frontier Pass". YouTube.

Cited sources

- Arismendi Posada, Ignacio (1983). Gobernantes Colombianos [Colombian Presidents] (second ed.). Bogotá, Colombia: Interprint Editors Ltd.; Italgraf.

- Bushnell, David; Langley, Lester D. (2008). Simón Bolívar: Essays on the Life and Legacy of the Liberator. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-5619-5.

- Grant, Will (5 July 2010). "Venezuela honors Simón Bolívar's lover Manuela Saenz". BBC. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- Lynch, John (2006). Simón Bolívar: A Life. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11062-3.

- Lynch, John (5 July 2007). Simón Bolívar: A Life. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12604-4.

- Masur, Gerhard (1969). Simón Bolívar (Revised ed.). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Petre, Francis Loraine (1910). Simon Bolivar "El libertador": a life of the chief leader in the revolt against Spain in Venezuela, New Granada & Peru. J. Lane.

- Rumazo González, Alfonso (2006). Antonio José de Sucre, Gran Mariscal de Ayacucho (Biografía). Ediciones de la Presidencia de la República. ISBN 978-980-03-0363-4.

- Rumazo González, Alfonso (2007). Manuela Sáenz. La Libertadora del Libertador (Biografía). Ediciones de la Presidencia de la República. ISBN 978-980-03-0369-6.

- Slatta, Richard W.; de Grummond, Jane Lucas (2003). Simón Bolívar's Quest for Glory. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-239-3.

- Thornton, John Kelly (28 April 1998). Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62724-5. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

Further reading

- Arana, Marie. Bolivar: American Liberator. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013.

- Bushnell, David. The Liberator, Simón Bolívar. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1970.

- Bushnell, David (ed.) and Fornoff, Fred (tr.), El Libertador: Writings of Simón Bolívar, Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-19-514481-9

- Bushnell, David and Macaulay, Neill. The Emergence of Latin America in the Nineteenth Century (Second edition). Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0-19-508402-3

- Ducoudray Holstein, H.L.V. Memoirs of Simón Bolívar. Boston: Goodrich, 1829.

- Gómez Martínez, José Luis. "La encrucijada del cambio: Simón Bolívar entre dos paradigmas (una reflexión ante la encrucijada postindustrial)". Cuadernos Americanos 104 (2004): 11–32.

- Harvey, Robert. "Liberators: Latin America's Struggle For Independence, 1810–1830". John Murray, London (2000). ISBN 978-0-7195-5566-4

- Higgins, James (editor). The Emancipation of Peru: British Eyewitness Accounts, 2014. Online at https://sites.google.com/site/jhemanperu

- Lacroix, Luis Perú de. Diario de Bucaramanga. Caracas: Ministerio del Poder Popular para la Comunicación y la Información, 2009.

- Ludwig, Emil. "Bolivar: The Life of an Idealist," Alliance Book Corporation, New York, 1942; popular biography

- Lynch, John. Simon Bolivar: A Life Paperback (Yale UP, 2007), a standard scholarly biography

- Lynch, John. Simón Bolívar and the Age of Revolution. London: University of London Institute of Latin American Studies, 1983. ISBN 978-0-901145-54-3

- Lynch, John. The Spanish American Revolutions, 1808–1826 (Second edition). New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1986. ISBN 978-0-393-95537-8

- Madariaga, Salvador de. Bolívar. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1952. ISBN 978-0-313-22029-6

- Masur, Gerhard (1948). Simón Bolívar (Second edition, translation by Pedro Martín de la Cámara). Bogotá: Fundación para la Investigación y la Cultura, 2008.

- Marx, Karl. "Bolívar y Ponte" in The New American Cyclopaedia: A Popular Dictionary of General Knowledge, Vol. III. New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1858.

- O'Leary, Daniel Florencio. Bolívar and the War of Independence/Memorias del General Daniel Florencio O'Leary: Narración (Abridged version). Austin: University of Texas, [1888] 1970. ISBN 978-0-292-70047-5

- Racine, Karen. "Simón Bolívar and friends: Recent biographies of independence figures in Colombia and Venezuela" History Compass 18#3 (Feb 2020) https://doi.org/10.1111/hic3.12608

External links

| Spanish Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Archivo del Libertador (In Spanish) –12,000+ transcribed documents of the Libertador, from 1799 to 1830.

- Simón Bolívar on In Our Time at the BBC

- The Life of Simón Bolívar

- The Louverture Project: Simón Bolívar – Information about the support Bolívar received from Haiti.

- In Profile: Simón Bolívar – The Liberator

- Biography of Simón Bolívar

- (in Spanish) Glrbv.org: Biography

- "Building a New History by Exhuming Bolívar" Simon Romero, The New York Times, 3 August 2010

- "Bolivar: American Liberator" on YouTube Lecture by Marie Arana, The John W. Kluge Center, The Library of Congress, 6 June 2013

- Simón Bolívar at Find a Grave

- Newspaper clippings about Simón Bolívar in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW