Pangasinan

Pangasinan (Pangasinan: Luyag na Panggasinan, [paŋɡasiˈnan];[4] Tagalog: Lalawigan ng Pangasinan) is a province in the Philippines located in the Ilocos Region of Luzon. Its capital is Lingayen. Pangasinan is on the western area of the island of Luzon along the Lingayen Gulf and West Philippine Sea. It has a total land area of 5,451.01 square kilometres (2,104.65 sq mi).[2] According to the 2015 census, it has a population of 2,956,726 people.[3] The official number of registered voters in Pangasinan is 1,651,814.[5] The western portion of the province is part of the homeland of the Sambal people, while the central and eastern portions are the homeland of the Pangasinan people. Due to ethnic migration, Ilocano people have settled in some areas of the province (ex.Rosales, Villasis, Urdaneta City).

Pangasinan | |

|---|---|

| Province of Pangasinan[1] | |

(2018-02-25).jpg) Pangasinan Provincial Capitol in Lingayen | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Etymology: Pang-asin-an, lit. Place where salt is made | |

| Anthem: Luyag Ko Tan Yaman | |

Location in the Philippines | |

| Coordinates: 15°55′N 120°20′E | |

| Country | Philippines |

| Region | Ilocos Region (Region I) |

| Founded | April 5, 1580 |

| Capital | Lingayen |

| Government | |

| • Type | Sangguniang Panlalawigan |

| • Governor | Amado Espino III |

| • Vice Governor | Mark Ronald D. Lambino |

| Area | |

| • Total | 5,451.01 km2 (2,104.65 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 15th out of 81 |

| Highest elevation (Mount Malico) | 1,675 m (5,495 ft) |

| Population (2015 census)[3] | |

| • Total | 2,956,726 |

| • Rank | 6th out of 81 |

| • Density rank | 11th out of 81 |

| including independent cities | |

| Demonym(s) | Pangasinense |

| Divisions | |

| • Independent cities | 1

|

| • Component cities | |

| • Municipalities | 44

|

| • Barangays |

|

| • Districts | 1st to 6th districts of Pangasinan (shared with Dagupan City) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (PST) |

| ZIP code | 2400–2447 |

| IDD : area code | +63 (0)75 |

| ISO 3166 code | PH-PAN |

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Languages |

|

| Website | www |

Pangasinan is the name for the province, the people, and the language spoken in the province. Indigenous Pangasinan speakers are estimated to number at least 2 million. The Pangasinan language, which is official in the province, is one of the officially recognized regional languages in the Philippines. In Pangasinan, there were several ethnic groups who enriched the cultural fabric of the province. Almost all of the people are Pangasinans and the rest are descendants of Bolinao and Ilocano, who settled the eastern and western parts of the province.[6] Pangasinan is spoken as a second-language by many of the ethnic minorities in Pangasinan. The secondary ethnic groups are the Bolinao-speaking Zambals and Ilocanos.

The name Pangasinan means "place of salt" or "place of salt-making"; it is derived from the prefix pang, meaning "for", the root word asin, meaning "salt”, and suffix an, signifying "location". The Spanish form of the province's name, Pangasinán, remains predominant, albeit without diacritics, and so does its pronunciation: [paŋɡasiˈnan]. The province is a major producer of salt in the Philippines. Its major products include bagoong ("salted-krill") and alamang ("shrimp-paste").

Pangasinan was first founded by Austronesian peoples who called themselves Anakbanwa by at least 2500 BC. A kingdom called Luyag na Caboloan, which expanded to incorporate much of northwestern Luzon, existed in Pangasinan before the Spanish conquest that began in the 16th century.[7] The Kingdom of Luyag na Kaboloan was known as the Wangdom of Pangasinan in Chinese records. The ancient Pangasinan people were skilled navigators and the maritime trade network that once flourished in ancient Luzon connected Pangasinan with other peoples of Southeast Asia, India, China, Japan and the rest of the Pacific. The ancient kingdom of Luyag na Caboloan was in fact mentioned in Chinese and Indian records as being an important kingdom on ancient trade routes.[7]

Popular tourist attractions in Pangasinan include the Hundred Islands National Park in Alaminos and the white-sand beaches of Bolinao and Dasol. Dagupan City is known for its Bangus Festival ("Milkfish Festival"). Pangasinan is also known for its delicious mangoes and ceramic oven-baked Calasiao puto ("native rice cake"). Pangasinan occupies a strategic geo-political position in the central plain of Luzon. Pangasinan has been described as a gateway to northern Luzon.

History

Ancient history

The Pangasinan people, like most of the people in the Malay Archipelago, are descendants of the Austronesian-speakers who settled in Southeast Asia since prehistoric times. Comparative genetics, linguistics and archaeological studies locate the origin of the Austronesian languages in Sundaland, which was populated as early as 50,000 years ago by modern humans.[8][9][10] The Pangasinan language is one of many languages that belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian languages branch of the Austronesian languages family.

Southeast Asian maritime trade network

A vast maritime trade network connected the distant Austronesian settlements in Southeast Asia, the Pacific and the Indian Ocean. The Pangasinan people were part of this ancient Austronesian civilization.

The ancient Austronesian-speakers were expert navigators. Their outrigger canoes and sailboats were capable of crossing the distant seas. The Malagasy sailed from the Malay archipelago to Madagascar, an island across the Indian Ocean, and probably reached Africa. As the possible predecessors of the Polynesians, large seagoing canoes called "bangka" ("vaka" in several Polynesian dialects and "waka" in Maori) were first developed by Austronesians in the Philippine archipelago which were then used to settle and establish long-distance trade networks with distant Pacific islands from the Micronesian island nations of Guam and Palau as far away as Hawaii and Easter Island and probably reached the Pacific coastline of the Americas. Proof of these trade exchanges are the prevalence of "kumara" or sweet potato in the Pacific Islands which is endemic to South America, and the abundance of chicken bones in ancient South American archaeological dig sites whose closest genetic relatives are those of chickens from Asia. At least three hundred years before the arrival of Europeans, the Makasar and the Bugis from Sulawesi, in what is now Indonesia, as well as the Sama-Bajaus of the Malay Archipelago, carried out long-distance commerce with their prau or paraw ("sailboat") and established settlements in north Australia, which they called Marege.[11]

Pangasinan was founded by Austronesian peoples who called themselves Anakbanwa during the Austronesian expansion from Taiwan and Southern China in about 5000–2500 BC or the Austronesian dispersal from Sundaland at least 7,000 years ago after the last Ice Age. Anakbanwa means “child of banwa.” Banwa (also spelled banua or vanua) is an Austronesian concept that could mean territory, homeland, habitat, society, civilization or cosmos. The Pangasinan people identified or associated banwa with the sun, which was their symbol for their banwa. The Pangasinan people are closely related to the Ibaloi in the neighboring province of Benguet and other peoples of Luzon. The Anakbanwa established their settlements in the banks of the Agno River and the coasts of Lingayen Gulf. The coastal area came to be known as Pangasinan, and the interior area came to be known as Kaboloan. Eventually, the whole region, its people and the used language came to be known as Pangasinan. Archaeological evidence and early Chinese and Indian records show that the inhabitants of Pangasinan traded with India, Arabia, China and Japan as early as the 8th century A.D.

Wangdom of Pangasinan (Luyag na Caboloan)

The Wangdom of Pangasinan (as known in Chinese records) and locally known as the ancient kingdom or state called Luyag na Caboloan (also spelled Kaboloan), with Binalatongan as its capital, existed in the fertile Agno River valley. Around the same period, the Srivijaya and Majapahit empires arose in Indonesia that extended their influence to much of the Malay Archipelago. Urduja/Udaya, a legendary woman warrior who Ibn Battuta called a rival of the Mongol Empire, is believed to have ruled in Pangasinan around the 14th century. The Luyag na Caboloan expanded the territory and influence of Pangasinan to what are now the neighboring provinces of Tarlac, La Union, Zambales, Nueva Ecija and Benguet. Pangasinan enjoyed full independence until the Spanish conquest.

Anito and mana beliefs and practices

The ancient Pangasinan people, like other Austronesian peoples, practiced anito worship. An anito was believed to be the spirit or divine power of an ancestor or the god or divine power in nature or natural phenomena. They believed in mana, an Austronesian concept which can be described as the divine power or vital or spiritual essence of every being and everything that exists. To the Pangasinan people, mana can be transferred, inherited or acquired, like from an ancestor, nature, or natural phenomena. Their belief or practice is similar to Shamanist or animist beliefs and rituals. They worshipped a pantheon of anito ("spirit" or "deity"). Their temples or altars were dedicated to a chief anito called Ama Kaoley or Ama-Gaolay[12] (“Supreme Father”), who communicated through mediums or priests called manag-anito. These manag-anito wore special costumes when serving an anito and they made offerings of oils, ointments, essences, and perfumes in exquisite vessels. In contrast, the Sambal people of the west also revered their own pantheon of deities, headed by the supreme god, Malayari.[13]

Spanish accounts of pre-Hispanic Pangasinan

In the sixteenth-century Pangasinan was called the "Port of Japan" by the Spanish. The locals wore native apparel typical of other maritime Southeast Asian ethnic groups in addition to Japanese and Chinese silks. Even common people were clad in Chinese and Japanese cotton garments. They blackened their teeth and were disgusted by the white teeth of foreigners, which were likened to that of animals. They used porcelain jars typical of Japanese and Chinese households. Japanese-style gunpowder weapons were encountered in naval battles in the area.[14] In exchange for these goods, traders from all over Asia would come to trade primarily for gold and slaves, but also for deerskins, civet and other local products. Other than a notably more extensive trade network with Japan and China, they were culturally similar to other Luzon groups to the south.

Pangasinans were also described as a warlike people who were long known for their resistance to Spanish conquest. Bishop Domingo Salazar described them as really the worst people, the fiercest and cruelest in the land. There was evidence of Christian influence even before Spanish colonization; they used vintage wine in small quantities for their sacramental practices. The church bragged that they won the northern part of the Philippines for Spain not Spanish military. They were unusually strict against adulterers, with the punishment being death for both parties. Pangasinans were known to take defeated Zambal (Aeta) and Negrito warriors to sell as slaves to Chinese traders.[15]

Christianity

In 1324, Odoric of Pordenone, a Franciscan missionary from Friuli, Italy, is believed by some to have celebrated a Catholic Mass and baptized natives at Bolinao, Pangasinan. In July 2007, memorial markers were set up in Bolinao to commemorate Odoric's journey based on a publication by Luigi Malamocco, an Italian priest from Friuli, Italy, who claimed that Odoric of Perdenone held the first Catholic Mass in the Philippines in Bolinao, Pangasinan. That 1324 mass would have predated the mass held in 1521 by Ferdinand Magellan, which is generally regarded as the first mass in the Philippines, by some 197 years. However, historian William Henry Scott concluded after examining Oderic's writings about his travels that he likely never set foot on Philippine soil and, if he did, there is no reason to think that he celebrated mass.[16]

Spanish colonization

On April 27, 1565, the Spanish conquistador Miguel López de Legazpi arrived in the Philippine islands with about 500 soldiers to establish a Spanish settlement and begin the conquest of the archipelago. On May 24, 1570, the Spanish forces defeated Rajah Sulayman and other rulers of Manila and later declared Manila as the new capital of the Spanish East Indies. After securing Manila, the Spanish forces continued to conquer the rest of the island of Luzon, including Pangasinan.

Provincia de Pangasinán

In 1571, the Spanish conquest of Pangasinan began with an expedition by the Spanish conquistador Martín de Goiti, who came from the Spanish settlement in Manila through Pampanga. About a year later, another Spanish conquistador, Juan de Salcedo, sailed to Lingayen Gulf and landed at the mouth of the Agno River. Limahong, a Chinese pirate, fled to Pangasinan after his fleet was driven away from Manila in 1574. Limahong failed to establish a colony in Pangasinan, as an army led by Juan de Salcedo chased him out of Pangasinan after a seven-month siege.

Pangasinan as a province dates its actual beginnings as an administrative and judicial district, with Lingayen as the capital, to as early as 1580, but its territorial boundaries were first delineated in 1611. Lingayen has remained the capital of the province except for a brief period during the revolutionary Era when San Carlos served as temporary administrative headquarters, and during the slightly longer Japanese Occupation when Dagupan was the capital.[17]

The province of Pangasinan was formerly classified as an alcaldía mayor de término, or first class civil province, during the Spanish regime and has, in fact, remained a first class-A province up to the present. Its territorial jurisdiction once included the entire province of Zambales and portions of what are now Tarlac and La Union provinces.[17]

Rebellion against the Spanish rule

Malong liberation

Andres Malong, a native chief of the town of Binalatongan (now named San Carlos City), liberated the province from Spanish rule in December 1660. The people of Pangasinan proclaimed Andres Malong Ari na Pangasinan ("King of Pangasinan"). Pangasinan armies attempted to liberate the neighboring provinces of Pampanga and Ilocos, but were repelled by a Spanish-led coalition of loyalist tribal warriors and mercenaries. In February 1661, the newly independent Kingdom of Pangasinan fell to the Spanish.

Palaris liberation

On November 3, 1762, the people of Pangasinan proclaimed independence from Spain after a rebellion led by Juan de la Cruz Palaris overthrew Spanish rule in Pangasinan. The Pangasinan revolt was sparked by news of the fall of Manila to the British on October 6, 1762. However, after the Treaty of Paris on March 1, 1763 that closed the Seven Years' War between Britain, France and Spain, the Spanish colonial forces made a counter-attack. On January 16, 1765, Juan de la Cruz Palaris was captured and Pangasinan independence was again lost.

Philippine revolution against Spain

The Katipunan, a nationalist secret society, was founded on July 7, 1892 with the aim of uniting the peoples of the Philippines and fighting for independence and religious freedom. The Philippine Revolution began on August 26, 1896 and was led by Andres Bonifacio, the leader of the Katipunan. On November 18, 1897, a Katipunan council was formed in western Pangasinan with Roman Manalang as Presidente Generalisimo and Mauro Ortiz as General. General Emilio Aguinaldo proclaimed Philippine independence on June 12, 1898. Dagupan City, the major commercial center of Pangasinan, was surrounded by Katipunan forces by July 18, 1898. The Battle of Dagupan lasted from July 18 to July 23 of that year with the surrender of 1,500 soldiers of the Spanish forces under Commander Federico J. Ceballos and Governor Joaquin de Orengochea.

The Battle of Dagupan, fought fiercely by local Katipuneros under the overall command of General Francisco Makabulos, chief of the Central and Directive Committee of Central and Northern Luzon, and the last remnants of the once mighty Spanish Army under General Francisco Ceballos, led to the liberation of Pangasinan from the Spaniards. The five-day battle was joined by three local heroes: Don Daniel Maramba from Santa Barbara, Don Vicente Prado from San Jacinto and Don Juan Quezada from Dagupan. Their armies massed in Dagupan to lay siege on the Spanish forces, making a last stand at the brick-walled Catholic Church.

Maramba led the liberation of the town of Santa Barbara on March 7, 1898 following a signal for simultaneous attack from Makabulos. Hearing that Santa Barbara fell into rebel hands, the Spanish forces in Dagupan attempted to retake the town, but were repulsed by Maramba's forces. Thus, after the setback, the Spaniards decided to concentrate their forces in Lingayen to protect the provincial capital. This enabled Maramba to expand his operations to Malasiqui, Urdaneta and Mapandan, taking them one after the other. He took one more town, Mangaldan, before proceeding to Dagupan to lay siege on the last Spanish garrison. Also on March 7, 1898, the rebels under the command of Prado and Quesada attacked convents in a number of towns in Zambales province, located west of Lingayen, which now constitute the western parts of Pangasinan.

Attacked and brought under Filipino control were Alaminos, Agno, Anda, Alos, Bani, Balincaguin, Bolinao, Dasol, Eguia and Potot. The revolt then spread to Labrador, Sual, Salasa and many other towns in the west. The towns of Sual, Labrador, Lingayen, Salasa and Bayambang were occupied first by the forces of Prado and Quesada before they proceeded to attack Dagupan.

At an assembly convened to organize a central governing body for Central and Northern Luzon on April 17, 1898, General Makabulos appointed Prado as politico-military governor of Pangasinan, with Quesada as his second in command. His appointment came a few days before the return of General Emilio Aguinaldo in May 1898 from his exile in Hong Kong following the signing of the Pact of Biac-na-Bato in December 1897. Aguinaldo's return gave fresh impetus to the renewal of the flame of the revolution. Thus, on June 3, 1898, General Makabulos entered Tarlac and from that day on, the fires of revolution spread.

So successful were the Filipinos in their many pitched battles against the Spaniards that on June 30, 1898, Spanish authorities decided to evacuate all their forces to Dagupan where a last stand against the rebels was to be made. They were ordered to go to Dagupan were all civilian and military personnel, including members of the volunteer locales of towns not yet in rebel hands. Those who heeded this order were the volunteer forces of Mangaldan, San Jacinto, Pozorrubio, Manaoag, and Villasis. Among the items brought to Dagupan was the image of the Most Holy Rosary of the Virgin of Manaoag, which was already the patron saint of Pangasinan.

When the forces of Maramba from the east and Prado from the west converged in Dagupan on July 18, 1898, the siege began. The arrival of General Makabulos strengthened the rebel forces until the Spaniards, holed up inside the Catholic Church, waved the flag of surrender five days later. Armed poorly, the Filipinos were no match at the very start with Spanish soldiers holed inside the Church. They just became mere sitting ducks to Spanish soldiers shooting with their rifles from a distance. But the tempo of battle changed when the attackers, under Don Vicente Prado, devised a crude means of protection to shield them from Spanish fire while advancing. This happened when they rolled trunks of bananas, bundled up in sawali, that enabled them to inch their way to the Church.

Northern Zambales ceded to Pangasinan

On November 30, 1903, several municipalities of northern Zambales, namely, Alaminos, Anda, Bani, Bolinao, Burgos, Dasol, Infanta and Mabini, were ceded to Pangasinan by the American colonial government in a bid for gerrymandering. These municipalities were traditional homelands of the Sambal people, who wanted to remain part of Zambales province, their ethnic province. This 1903 colonial decision has yet to be reverted.[18]

American colonization and the Philippine Commonwealth regime

Pangasinan and other parts of the Spanish East Indies were ceded to the Americans after the Treaty of Paris that closed the Spanish–American War. During the Philippine–American War, Lieutenant Col. Jose Torres Bugallon from the town of Salasa fought together with Gen. Antonio Luna to defend the First Philippine Republic against American colonization of Northern Luzon. Bugallon was killed in battle on February 5, 1899. The First Philippine Republic was abolished in 1901. In 1907, the Philippine Assembly was established and for the first time, five residents of Pangasinan were elected as its district representatives. In 1921, Mauro Navarro, representing Pangasinan in the Philippine Assembly, sponsored a law to rename the town of Salasa to Bugallon in order to honor General Bugallon.

During the Philippine Commonwealth regime, Manuel L. Quezon was inaugurated as the first president of the Commonwealth of the Philippines under the collaboration from the United States of America on November 15, 1935.

The 21st Infantry Division, Philippine Commonwealth Army, USAFFE was found military establishment and built of the general headquarters was active on July 26, 1941 to June 30, 1946 and they stationed in Pangasinan during the pre-World War II era. From the conflict engagements of the Anti-Japanese Imperial military operations included the fall of Bataan and Corregidor and aiding the USAFFE ground force from January to May 1942 and the Japanese Insurgencies and Allied Liberation in Pangasinan from 1942 to 1945 and some parts in North-Central Luzon and helps local guerrillas and American forces against the Japanese.

Philippine Republic

National

1946–1986

After the declaration of Independence in Manila on July 4, 1946, Eugenio Perez, a Liberal Party congressman representing the fourth district of Pangasinan, was elected Speaker of the lower Legislative House. He led the House until 1953, when the Nacionalista Party became the dominant party.

Pangasinan, which is historically and geographically part of the Central Luzon Region, is made politically part of the Ilocos Region (Region I) in the gerrymandering of the Philippines by Ferdinand Marcos, despite the fact that Pangasinan has its distinct primary language, which is Pangasinan. The political classification of Pangasinan as part of the Ilocos Region has generated confusion among some Filipinos that the residents of Pangasinan are Ilocanos, even though Ilocanos only constitute a significant minority in the province. Pangasinan has a distinct primary language, ethnic group and culture, its economy is bigger than the predominantly Ilocano provinces of Ilocos Norte, Ilocos Sur and La Union and its population is more than 50 percent of the population of Region 1.

1986–present

In February 1986, Vice Chief of Staff General Fidel V. Ramos, head of the Philippine Integrated National Police and a native of Lingayen, Pangasinan, became one of the instrumental figures of the EDSA people power revolution that led to the overthrow of President Ferdinand Marcos.

After the downfall of Marcos, all local government unit executives in the Philippines were ordered by President Corazon Aquino to vacate their posts. Some local executives were ordered to return to their seats as in the case of Mayor Ludovico Espinosa of Dasol, where he claims he joined the UNIDO, Mrs. Aquino's party during the height of the EDSA Revolution. Fidel Ramos was appointed as AFP Chief of Staff and later as Defense Secretary replacing Juan Ponce Enrile. Oscar Orbos, a congressman from Bani, Pangasinan, was appointed by Aquino as head of the Department of Transportation and Communications and later as Executive Secretary.

On May 11, 1992, Fidel V. Ramos ran for the position of President. He was elected and became the first Pangasinan President of the Philippines. Through his leadership, the Philippines recovered from a severe economy after the oil and power crisis of 1991. His influence also sparked the economic growth of Pangasinan when it hosted the 1995 Palarong Pambansa (Philippine National Games).

Jose de Venecia, who represented the same district as Eugenio Perez, was the second Pangasinan to be Speaker of the House of Representatives in 1992. He was reelected for the same position in 1995. De Venecia was selected by the Ramos' administration party Lakas NUCD to be its presidential candidate in 1998. De Venecia ran but lost to Vice President Joseph Estrada. Oscar Orbos, who served as Pangasinan governor from 1995, ran for Vice President, but lost to Senator Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, whose mother, former First Lady Evangelina Macaraeg-Macapagal, hails from Binalonan, Pangasinan.

Arroyo later ascended to the presidency after the second EDSA Revolution when President Joseph Estrada was overthrown.

In May 2004, actor-turned-politician Fernando Poe, Jr., whose family is from San Carlos City, Pangasinan, ran for President against incumbent Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo during the Philippine general election in 2004. The Pangasinan vote was almost evenly split by the two presidential candidates who both have Pangasinan roots. Arroyo was elected President, but her victory was tainted by charges of electoral fraud and vote-buying.

Geography

Physical

Pangasinan is located on the west central area of the island of Luzon in the Philippines. It is bordered by La Union to the north, Benguet and Nueva Vizcaya to the northeast, Nueva Ecija to the southeast, and Zambales and Tarlac to the south. To the west of Pangasinan is the South China Sea. The province also encloses the Lingayen Gulf.

The province has a land area of 5,451.01 square kilometres (2,104.65 sq mi).[19] It is 170 kilometres (110 mi) north of Manila, 50 kilometres (31 mi) south of Baguio, 115 kilometres (71 mi) north of Subic International Airport and Seaport, and 80 square kilometres (31 sq mi) north of Clark International Airport. At the coast of Alaminos, the Hundred islands have become a famous tourist spot.

The terrain of the province, as part of the Central Luzon plains, is typically flat, with a few parts being hilly and/or mountainous. The northeastern municipalities of San Manuel, San Nicolas, Natividad, San Quintin and Umingan have hilly to mountainous areas, situated at the tip of the Cordillera mountains. The Zambales mountains extend to the province's western towns of Labrador, Mabini, Bugallon, Aguilar, Mangatarem, Dasol, and Infanta forming the mountainous portions of those towns.

The Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS) reported several inactive volcanoes in the province: Amorong, Balungao, Cabaluyan, Cahelietan, Candong, and Malabobo. PHIVOLCS reported no active or potentially active volcanoes in Pangasinan. A caldera-like landform is located between the towns of Malasiqui and Villasis with a center at about 15° 55′ N and 120° 30′ E near the Cabaruan Hills.

Several rivers traverse the province. The longest is the Agno River, which originates from the Cordillera Mountains of Benguet, eventually emptying its waters into the Lingayen Gulf. Other major rivers include the Bued River, Angalacan River, Sinocalan River, Patalan River and the Cayanga River.

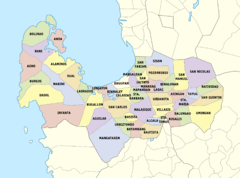

Administrative divisions

The province of Pangasinan is subdivided into 44 municipalities, 4 cities, and 1,364 barangay (which means "village" or "community"). There are six congressional districts in the province.

The capital of the province is Lingayen. In ancient times, the capital of Pangasinan was Binalatongan, now San Carlos.

Cities

- Alaminos

- Dagupan (independent)

- San Carlos

- Urdaneta

Municipalities

- Agno

- Aguilar

- Alcala

- Anda

- Asingan

- Balungao

- Bani

- Basista

- Bautista

- Bayambang

- Binalonan

- Binmaley

- Bolinao

- Bugallon

- Burgos

- Calasiao

- Dasol

- Infanta

- Labrador

- Laoac

- Lingayen

- Mabini

- Malasiqui

- Manaoag

- Mangaldan

- Mangatarem

- Mapandan

- Natividad

- Pozorrubio

- Rosales

- San Fabian

- San Jacinto

- San Manuel

- San Nicolas

- San Quintin

- Santa Barbara

- Santa Maria

- Santo Tomas

- Sison

- Sual

- Tayug

- Umingan

- Urbiztondo

- Villasis

Barangays

Pangasinan has 1,364 barangays comprising its 44 municipalities and 4 cities, ranking the province at 3rd with the most number of barangays in a Philippine province, only behind the Visayan provinces of Leyte and Iloilo.

The most populous barangay in the province is Bonuan Gueset in Dagupan City, with a population of 22,042 in 2010. If cities are excluded, Poblacion in the municipality of Lingayen has the highest population at 12,642. Iton in Bayambang has the lowest with only 99 in the census of 2010.[20]

Demographics

Population

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1903 | 442,521 | — |

| 1918 | 565,922 | +1.65% |

| 1939 | 742,475 | +1.30% |

| 1948 | 920,491 | +2.42% |

| 1960 | 1,124,144 | +1.68% |

| 1970 | 1,386,143 | +2.11% |

| 1975 | 1,520,085 | +1.87% |

| 1980 | 1,636,057 | +1.48% |

| 1990 | 2,020,273 | +2.13% |

| 1995 | 2,178,412 | +1.42% |

| 2000 | 2,434,086 | +2.41% |

| 2007 | 2,645,395 | +1.15% |

| 2010 | 2,779,862 | +1.82% |

| 2015 | 2,956,726 | +1.18% |

| Source: Philippine Statistics Authority [3][20][21][22] | ||

The population of Pangasinan in the 2015 census was 2,956,726 people,[3] with a density of 540 inhabitants per square kilometre or 1,400 inhabitants per square mile.

The Pangasinan people (Totoon Pangasinan) are called Pangasinan or the Hispanicized name Pangasinense, or simply taga-Pangasinan, which means "from Pangasinan". Pangasinan people were known as traders, businesspeople, farmers and fishers. Pangasinan is the third most-populated province in the Philippines. The estimated population of the indigenous speakers of the Pangasinan language in the province of Pangasinan is almost 2 million and is projected to double in about 30 years. According to the 2000 census, 47 percent of the population are native Pangasinan and 44 percent are Ilocano settlers. Indigenous Sambal people predominate in the westernmost municipalities of Bolinao and Anda. The Pangasinan people are closely related to the Austronesian-speaking peoples of the other parts of the Philippines, as well as Indonesia and Malaysia.

Languages

The Pangasinan language is an agglutinative language. It belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian languages branch of the Austronesian language family and is the primary language of the province of Pangasinan, as well as northern Tarlac and southwestern La Union. The Pangasinan language is similar to the other Malayo-Polynesian languages of the Philippines, as well as Indonesia and Malaysia. It is closely related to the Ibaloi language spoken in the neighboring province of Benguet, located northwest of Pangasinan. The Pangasinan language along with Ibaloi are classified under the Pangasinic group of languages. The other Pangasinic languages are:

- Karao

- Iwaak

- Keley-I

- I-Kallahan

Aside from their native language, some educated Pangasinans are highly proficient in Ilocano, English and Filipino. Pangasinan is mostly spoken in the central part of the province in the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and is the second language in other parts of Pangasinan. Ilocano is widely spoken in the westernmost and easternmost parts of Pangasinan in the 1st, 5th and 6th districts, and is the second language in other parts of Pangasinan. Ilocanos and Pangasinans speak Ilocano with a Pangasinan accent, as descendants of Ilocanos from first generation who lived within Pangasinan population learned Pangasinan language. Bolinao, a Sambalic language is widely spoken in the western tip of the province in the towns of Bolinao and Anda.

Religion

The religion of the people of Pangasinan is predominantly Christianity with Roman Catholicism as the overwhelming majority at 80% affiliation in the population. The second major denomination in the province is the Aglipayan Church with at least 15% of the population. Other religious denominations are divided with other Christian groups such as Members Church of God International, Iglesia Ni Cristo, Baptist, Methodist, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormon), Jehovah's Witnesses and Seventh-day Adventist. Few are strict believers and continue to practice their indigenous anito beliefs and rituals, like most of the people of the Philippines.

Spanish and American missionaries introduced Christianity to Pangasinan. Prior to the Spanish conquest in 1571, the predominant religion of the people of Pangasinan was similar to the indigenous religion of the highland Igorot or the inhabitants of the Cordillera Administrative Region on the island of Luzon, who mostly retained their indigenous culture and religion. A translation of the New Testament (excluding Revelation) in the Pangasinan language by Fr. Nicolas Manrique Alonzo Lallave, a Spanish Dominican friar assigned in Urdaneta, was the first ever translation of a complete portion of the Bible in a Philippine language. Pangasinan was also influenced by Hinduism, Buddhism and Islam to a lesser extent, before the introduction of Christianity. Some Pangasinense people have reverted to their indigenous religion headed by their supreme deity, Ama Kaoley or Ama-Gaolay,[12] while some Sambal people of the west have also reverted to their indigenous religion, headed by the supreme god, Malayari.[13]

Economy

The province's economy is mainly agricultural due to its vast fertile plains. More than 44 percent of its agricultural area is devoted to crop production. Aside from being one of the Philippine's rice granaries, Pangasinan is also a major producer of coconut, mango and eggplant, Pangasinan is the richest province in Ilocos Region of the Philippines.[24]

Energy

The 1200 megawatt Sual coal-fired power plant, and 345 megawatt San Roque multi-purpose dam, in the municipalities of Sual and San Manuel respectively, are the primary sources of energy of the province.

Marine

Pangasinan is a major fish supplier in Luzon, and a major producer of salt in the Philippines. It has extensive fishponds, mostly for raising bangus or "milkfish", along the coasts of the Lingayen Gulf and the South China Sea. Pangasinan's aquaculture includes oyster and sea urchin farms.

Salt is also a major industry. In salt evaporation ponds seawater is mixed with sodium bicarbonate until the water evaporates and the salt remains. This is their ancient tradition inspired from Egypt.

Agriculture

The major crops in Pangasinan are rice, mangoes, corn, and sugar cane. Pangasinan has a land area of 536,819 hectares, and 44 percent of the total land area of Pangasinan is devoted to agricultural production.

Financial

Pangasinan has 593 banking and financing institutions.

Labor

Pangasinan has a labor force of about 1.52 million, and 87 percent of the labor force are gainfully employed.

Health and education

There are thousands of public schools and hundreds of private schools across the province for primary and secondary education. Many Pangasinans go to Metro Manila, Baguio City, and the United States for tertiary and higher education.

Pangasinan has 51 hospitals and clinics and 68 rural health units (as of July 2002). Although some residents go to other parts of the Philippines, Metro Manila, Europe and the United States for extensive medical tests and treatment, almost all Pangasinans go to the major medical centers in the cities of Dagupan, San Carlos and Urdaneta.

Culture

The culture of Pangasinan is a blend of the indigenous Malayo-Polynesian and western Hispanic culture, with some Indian and Chinese influences and minor American influences. Today, Pangasinan is very much westernized, yet retains a strong, native Austronesian background.

The main centers of Pangasinan culture are Dagupan City, Lingayen, Manaoag, Calasiao, and San Carlos City.

Government

The current governor of Pangasinan is Amado "Pogi" Espino, III, son of former governor Amado T. Espino, Jr., and the current vice governor is Mark Ronald Lamibino, son of Cagayan Economic Zone Authority (CEZA) and Presidential Adviser for Northern Luzon Raul Lambino. Among those who served as Governor of Pangasinan include Francisco Duque Jr., former Secretary of Department of Health (Philippines), Conrado Estrella, secretary of Department of Agrarian Reform during the presidency of Ferdinand Marcos, Tito Primicias, Vicente Millora and Daniel Maramba.

Here are the other newly-elected officials to be sworn in effective June 30, 2019:

District Representatives (2019–2022)

- 1st District: Arnold F. Celeste

- 2nd District: Jumel Anthony I. Espino

- 3rd District: Rosemarie J. Arenas

- 4th District: Christopher George P. De Venecia

- 5th District: Ramon V. Guico III

- 6th District: Tyrone D. Agabas

Provincial Board Members (2019–2022)

- 1st District: Donabel N. Fontelera and Margielou Orange H. Versoza

- 2nd District: Nestor D. Reyes and Von Mark R. Mendoza

- 3rd District: Vici M. Ventanilla and Angel M. Baniqued, Jr.

- 4th District: Jeremy Agerico B. Rosario and Liberato Z. Villegas

- 5th District: Rosary Gracia P. Perez- Tababa and Nicholi Jan Louie Q. Sison

- 6th District: Noel C. Bince and Salvador S. Perez Jr.

- Liga ng mga Barangay Provincial President: Jose G. Peralta Jr.

- PCL Pangasinan President: Shiela Marie S. Perez-Galicia

- Sangguniang Kabataan Provincial President: Jerome Vic O. Espino

Notable people

Notable people either born or residing in Pangasinan include:

- James Reid ABS-CBN Actor, singer and model, whose mother is from Bolinao.

- Fernando Poe Sr., former action star, from San Carlos City.

- Eva Macapagal, First Lady of the Philippines in 1961–1965 and mother of Former President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, was from Binalonan.

- President Fidel V. Ramos, who was born in Lingayen and hails from Asingan.

- Senator Leticia Ramos-Shahani (Senator of the Philippines, 1987–1998), born in Lingayen and hails from Asingan.

- Speaker Eugenio Perez (1896–1996), first Speaker of the House of Representatives (Philippines) from Pangasinan and born in Basista.

- Dr. Francisco Duque III, current Secretary of Department of Health (Philippines) (2017–present)

- Retired Gen. Isidro Lapena, former commissioner of Bureau of Customs and former director of Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA). Present Secretary-General of Technical Education and Skills Development Authority

- Francisco Baraan III, former Senior Board Member of Pangasinan (1995-1998; 1998-2001); former Justice Undersecretary of the Philippines (2012-2016; under Benigno Aquino II)

- Manuel Moran, former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, who was born in Binalonan.

- Gabriel C. Singson, the former governor of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, is from Lingayen.

- Carlos Bulosan, internationally known writer from Binalonan.

- Francisco Sionil José, internationally known writer from Rosales.

- Victorio Edades, a Filipino modernist and a recognized National Artist, was from Dagupan City.

- Jacqueline Aquino Siapno, a professor from Dagupan City, is the interim first lady of East Timor.

- Geronima Tomelden-Pecson, the first female senator of the Philippines, was a native of Lingayen.

- Julius Babao, ABS-CBN news anchor, TV/Radio host, born in Dagupan City.

- Cheryl Cosim, TV5 news anchor, TV/Radio host is from Dagupan City.

- Mitoy Yonting, first winner of The Voice of the Philippines, lead singer Draybers., from Calasiao.

- Danny Ildefonso, two-time PBA Season MVP, five-time Best Player of the Conference, three-time Finals MVP, All-Star Game MVP, Rookie of the Year, Comeback Player of the Year, eight-time PBA Champion and one of the 40 Greatest Players in PBA History, from Urdaneta City.

- Marc Pingris, two-time Finals MVP, three-time Defensive Player of the Year, All-Star Game MVP, Most Improved Player, eight-time PBA Champion and one of the 40 Greatest Players in PBA History, from Pozorrubio

- Marlou Aquino, Rookie of the Year, Best Player of the Conference, Defensive Player of the Year, three-time PBA Champion and one of the 40 Greatest Players in PBA History, from Santa Barbara.

- Lordy Tugade, Finals MVP and PBA Champion, from Alaminos.

- Ana "The Hurricane" Julaton, a native of Pozorrubio, World Boxing Champion

- Oscar Orbos, a native of Bani, a former governor and TV host.

- Thomas Orbos, current undersecretary of Department of Transportation (Philippines), brother of former Governor Oscar Orbos, natives from the town of Bani.

- Gloria Romero, a veteran actress, hails from Mabini.

- Nova Villa, GMA veteran actress, from Mangatarem

- Maki Pulido, GMA news anchor, hails from Anda.

- Narciso Ramos, a journalist, lawyer, assemblyman and ambassador, and the father of former president Fidel V. Ramos., born in Asingan.

- Barbara Perez, veteran actress, born in Urdaneta City.

- Lolita Rodriguez, actress, born in Urdaneta City.

- Carmen Rosales, former actress, born in Rosales.

- Hermogenes Esperon Jr., Former AFP Chief of Staff and current adviser of National Security Council (Philippines), born in Asingan.

- Papa Jack, TV Radio Broadcaster and DJ, from Alcala.

- Mocha Uson, Assistant Secretary of Presidential Communications Operations Office (PCOO), born in Dagupan City.

- Jhong Hilario, ABS-CBN dancer and actor, born in Asingan.

- Jane Oineza, ABS-CBN Teen Actress from Bani.

- Anne Curtis, ABS-CBN Actress and fashion model, whose mother is from Bolinao.

- Liza Soberano, ABS-CBN Actress, fashion model and singer, whose father is from Asingan.

- Romeo de la Cruz, former Solicitor General of the Philippines from Urdaneta City.

See also

- Pangasinan literature

- Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Lingayen-Dagupan

- Roman Catholic Diocese of Alaminos

- Roman Catholic Diocese of Urdaneta

References

- (Pangasinan: Luyag na Pangasinan; Tagalog: Lalawigan ng Pangasinan; Ilocano: Probinsia ti Pangasinan)

- "List of Provinces". PSGC Interactive. Makati City, Philippines: National Statistical Coordination Board. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- Census of Population (2015). "Region I (Ilocos Region)". Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. PSA. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- Benton, Richard A. (1971). Pangasinan Reference Grammar. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8248-7910-5.

- ""Pangasinan voters already 1,651,814," Sunday Punch. December 10, 2012". Archived from the original on 2013-05-17. Retrieved 2012-12-26.

- Minahan, James (10 June 2014). Ethnic Groups of South Asia and the Pacific. ABC-CLIO. p. 34. ISBN 978-1598846607. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- New DNA evidence overturns population migration theory in Island Southeast Asia – University of Oxford Archived 2011-10-28 at the Wayback Machine

- New research forces U-turn in population migration theory

- Mark Donohue; Tim Denham (2010). "Farming and language in Island Southeast Asia: Reframing Austronesian history". Current Anthropology. 51 (2): 223–256. doi:10.1086/650991.

- PLoS ONE: The History of Makassan Trepang Fishing and Trade

- https://ncca.gov.ph/about-ncca-3/subcommissions/subcommission-on-cultural-communities-and-traditional-arts-sccta/northern-cultural-communities/the-lowland-cultural-community-of-pangasinan/

- https://www.aswangproject.com/sambal-mythology-pantheon-of-deities-and-beings/

- Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay. Manila Philippines: Ateneo de Manila University Press. p. 187.

- Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay. Manila Philippines: Ateneo de Manila University Press. pp. 248–249.

- Scott, William Henry (1984). Prehispanic source materials for the study of Philippine history. New Day Publishers. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-971-10-0226-8.

- "History of Pangasinan". Archived from the original on 5 September 2014. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- Bautista, Joseph. "Agno Rustic Pangasinan 0". The Manila Times. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- "Province: Pangasinan". PSGC Interactive. Quezon City, Philippines: Philippine Statistics Authority. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- Census of Population and Housing (2010). "Region I (Ilocos Region)". Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay. NSO. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- Censuses of Population (1903–2007). "Region I (Ilocos Region)". Table 1. Population Enumerated in Various Censuses by Province/Highly Urbanized City: 1903 to 2007. NSO.

- "Province of Pangasinan". Municipality Population Data. Local Water Utilities Administration Research Division. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- Table 10. Household Population by Country of Citizenship and Sex: 2010

- http://www.coa.gov.ph/index.php/local-government-units-lgus/category/6072-2015?download=28070:annual-financial-report-for-local-government-volume-i

- Bibliography

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A. History of the Filipino People. (Quezon City: Garotech Publishing, Eighth Edition, 1990).

- Cortes, Rosario Mendoza. Pangasinan, 1572–1800. (Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press, 1974; New Day Publishers, 1975).

- Cortes, Rosario Mendoza. Pangasinan, 1801–1900: The Beginnings of Modernization. (Cellar Book Shop, April 1991).

- Cortes, Rosario Mendoza. Pangasinan, 1901–1986: A Political, Socioeconomic, and Cultural History. (Cellar Book Shop, April 1991).

- Cortes, Rosario Mendoza. The Filipino Saga: History as Social Change. (Quezon City: New Day Publishers, 2000).

- Craig, Austin. "Lineage Life and Labors of Jose Rizal". (Manila: Philippine Education Company, 1913).

- Mafiles, Victoria Veloria; Nava, Erlinda Tomelden. The English Translations of Pangasinan Folk Literature. (Dagupan City, Philippines: Five Ed Printing Press, 2004).

- Quintos, Felipe Quintos. Sipi Awaray Gelew Diad Pilipinas (Revolucion Filipina). (Lingayen, Pangasinan: Gumawid Press, 1926).

- Samson-Nelmida, Perla. Pangasinan Folk Literature, A Doctoral Dissertation. (University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City: May 1982).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pangasinan. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Pangasinan. |

- Official Tourism Website of Pangasinan

- Official Website of the Provincial Government of Pangasinan

- Provincial Profile at the National Competitiveness Council of the Philippines

- Local Governance Performance Management System

- Pangasinan Wikipedia

- Salt production in Pangasinan

- Philippine Standard Geographic Code

- Philippine Census Information