Congress of the Philippines

Congress of the Philippines (Filipino: Kongreso ng Pilipinas) is the national legislature of the Philippines. It is a bicameral body consisting of the Senate (upper chamber), and the House of Representatives (lower chamber),[1] although colloquially, the term "Congress" commonly refers to just the latter.

Congress of the Philippines Kongreso ng Pilipinas | |

|---|---|

| 18th Congress of the Philippines | |

Seals of the Senate (left) and of the House of Representatives (right) | |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Houses | Senate House of Representatives |

| Leadership | |

| Structure | |

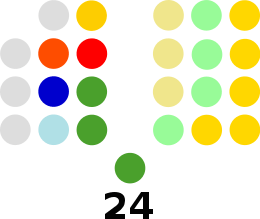

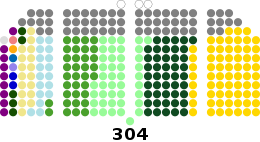

| Seats | 328 (see list) 24 senators 304 representatives |

| |

Senate political groups | Majority bloc (20):

Minority bloc (4): |

| |

House of Representatives political groups | Majority bloc (271)

Minority bloc (30)

Independent minority bloc (2)

Vacancy (2)

|

Joint committees | Joint committees are chaired by senators |

| Authority | Article VI, Constitution of the Philippines |

| Elections | |

| Multiple non-transferable vote | |

| Parallel voting (Party-list proportional representation and first-past-the-post) | |

Senate last election | May 13, 2019 |

House of Representatives last election | May 13, 2019 |

Senate next election | May 9, 2022 |

House of Representatives next election | May 9, 2022 |

| Meeting place | |

| Senate: Government Service Insurance System Building, Pasay House of Representatives:  Batasang Pambansa Complex, Quezon City | |

| Website | |

| Senate of the Philippines House of Representatives of the Philippines | |

The Senate is composed of 24 senators[2] half of which are elected every three years. Each senator, therefore, serves a total of six years. The senators are elected by the whole electorate and do not represent any geographical district.

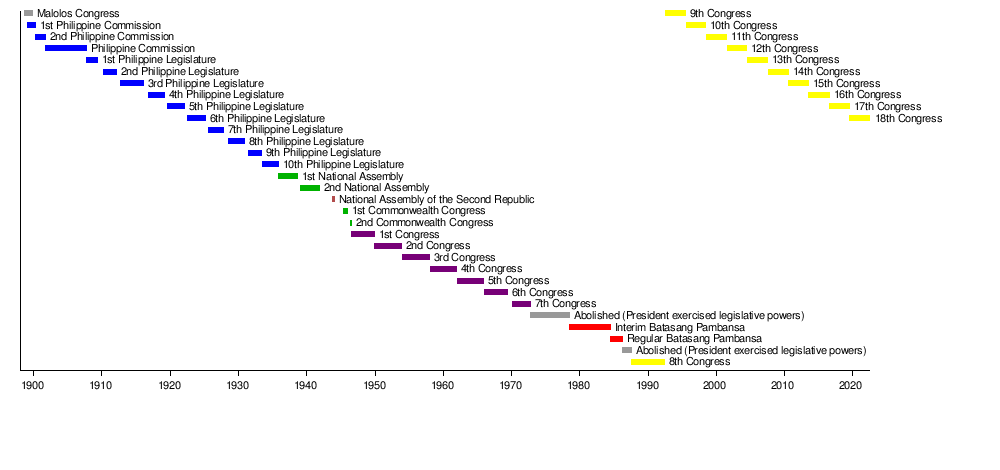

In the ongoing 18th Congress, there are 304 seats in the House of Representatives. The Constitution states that the House "shall be composed of not more than 250 members, unless otherwise fixed by law," and that at least 20% of it shall be sectoral representatives. There are two types of congressmen: the district and the sectoral representatives. At the time of the ratification of the constitution, there were 200 districts, leaving 50 seats for sectoral representatives.

The district congressmen represent a particular congressional district of the country. All provinces in the country are composed of at least one congressional district. Several cities also have their own congressional districts, with some having two or more representatives.[1] From 200 districts in 1987, the number of districts have increased to 243. Every new Congress has seen an increase in the number of districts.

The party-list congressmen represent the minority sectors of the population. This enables these minority groups to be represented in the Congress, when they would otherwise not be represented properly through district representation. Also known as party-list representatives, sectoral congressmen represent labor unions, rights groups, and other organizations.[1] With the increase of districts also means that the seats for party-list representatives increase as well, as the 1:4 ratio has to be respected.

The Constitution provides that Congress shall convene for its regular session every year beginning on the 4th Monday of July. A regular session can last until thirty days before the opening of its next regular session in the succeeding year. The President may, however, call special sessions which are usually held between regular legislative sessions to handle emergencies or urgent matters.[1]

History

Spanish era

During the Spanish colonization of the Philippines, municipal governments, or Cabildos were established. One such example was the Cabildo in Manila, established in 1571.[3]

When the Philippines was under colonial rule as part of the Spanish East Indies, the colony was not given representation to the Spanish Cortes. It was only in 1809 where the colony was made an integral part of Spain and was given representation in the Cortes. While colonies such as the Philippines were selecting its delegates, substitutes were named so that the Cortes can convene. The substitutes, and first delegates for the Philippines were Pedro Pérez de Tagle and José Manuel Couto. Both had no connections to the colony.[4]

By July 1810, Governor General Manuel González de Aguilar received the instruction to hold an election. As only the Manila Municipal Council qualified to elect a representative, it was tasked to select a delegate. Three of its representatives, the governor-general and the Archbishop of Manila selected Ventura de los Reyes as Manila's delegate to the Cortes. De los Reyes arrived in Cadiz in December 1811.[4]

However, with Napoleon I's defeat at the Battle of Waterloo, his brother Joseph Bonaparte was removed from the Spanish throne, and the Cádiz Constitution was replaced by the Cortes on May 24, 1816 with a more conservative constitution that removed Philippine representation on the Cortes, among other things. Restoration of Philippine representation to the Cortes was one of the grievances by the Ilustrados, the educated class during the late 19th century.[2]

Revolutionary era

The Illustrados' campaign transformed into the Philippine Revolution that aimed to overthrow Spanish rule. Proclaiming independence on June 12, 1898, President Emilio Aguinaldo then ordered the convening of a revolutionary congress at Malolos. The Malolos Congress, among other things, approved the Malolos Constitution. With the approval of the Treaty of Paris, the Spanish ceded the Philippines to the United States. The revolutionaries, attempting to prevent American conquest, launched the Philippine–American War, but were defeated when Aguinaldo was captured in 1901.[2]

American era

When the Philippines was under American colonial rule, the legislative body was the Philippine Commission which existed from 1900 to 1907. The President of the United States appointed the members of the Philippine Commission. Furthermore, two Filipinos served as Resident Commissioners to the House of Representatives of the United States from 1907 to 1935, then only one from 1935 to 1946. The Resident Commissioners had a voice in the House, but did not have voting rights.[2]

The Philippine Bill of 1902 mandated the creation of a bicameral or a two-chamber Philippine Legislature with the Philippine Commission as the Upper House and the Philippine Assembly as the Lower House. This bicameral legislature was inaugurated in 1907. Through the leadership of then Speaker Sergio Osmeña and then-Floor Leader Manuel L. Quezon, the Rules of the 59th United States Congress were substantially adopted as the Rules of the Philippine Legislature.[2]

In 1916, the Jones Law changed the legislative system. The Philippine Commission was abolished, and a new bicameral Philippine Legislature consisting of a House of Representatives and a Senate was established.[2]

Commonwealth and Second Republic era

The legislative system was changed again in 1935. The 1935 Constitution, aside from instituting the Commonwealth which gave the Filipinos more role in government, established a unicameral National Assembly. But in 1940, through an amendment to the 1935 Constitution, a bicameral Congress of the Philippines consisting of a House of Representatives and a Senate was created. Those elected in 1941 would not serve until 1945, as World War II erupted. The invading Japanese set up the Second Philippine Republic and convened its own National Assembly. With the Japanese defeat in 1945, the Commonwealth and its Congress was restored. The same setup continued until the Americans granted independence on July 4, 1946.[2]

Independent era

Upon the inauguration of the Republic of the Philippines on July 4, 1946, Republic Act No. 6 was enacted providing that on the date of the proclamation of the Republic of the Philippines, the existing Congress would be known as the First Congress of the Republic. Successive Congresses were elected until President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law on September 23, 1972. Marcos then ruled by decree.[2]

As early as 1970, Marcos had convened a constitutional convention to revise the 1935 constitution; in 1973, the Constitution was approved. It abolished the bicameral Congress and created a unicameral National Assembly, which would ultimately be known as the Batasang Pambansa in a semi-presidential system of government. The batasan elected a prime minister. The Batasang Pambansa first convened in 1978. [2]

Marcos was overthrown after the 1986 People Power Revolution; President Corazon Aquino then ruled by decree. Later that year she appointed a constitutional commission that drafted a new constitution. The Constitution was approved in a plebiscite the next year; it restored the presidential system of government together with a bicameral Congress of the Philippines. It first convened in 1987.[2]

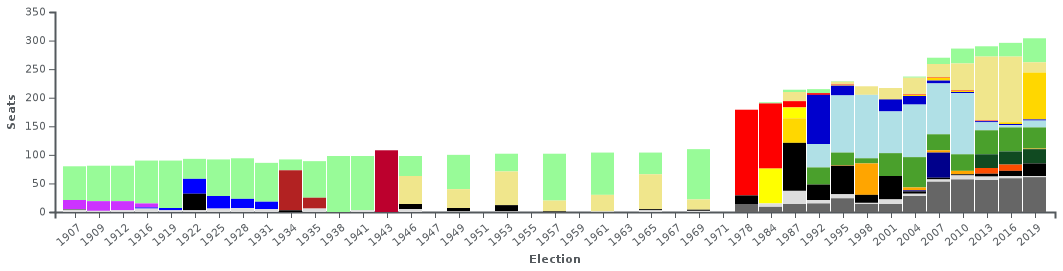

List

Timeline

- Legend

The winners of the 1941 election first took office in 1945. See 1st Congress of the Commonwealth of the Philippines for details.

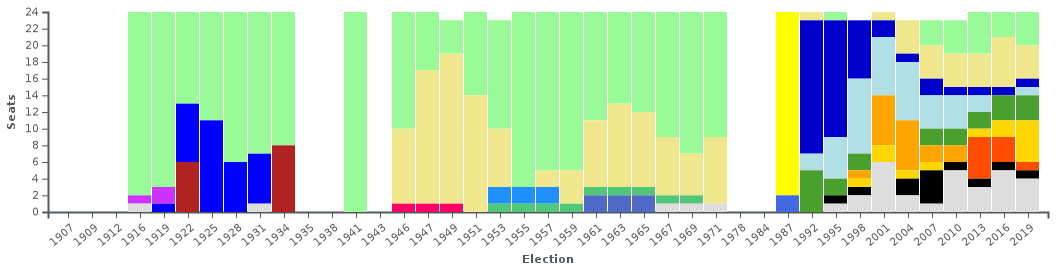

Senate

House of Representatives

Chronological

Seat

In what could be a unique setup, the two houses of Congress meet at different places in Metro Manila, the seat of government: the Senate meets at the GSIS Building, the main office of the Government Service Insurance System (GSIS) at Pasay, while the House of Representatives sits at the Batasang Pambansa Complex in Quezon City. The two are around 25 kilometers (16 mi) apart.

The Barasoain Church in Malolos, Bulacan served as a meeting place of unicameral congress of the First Philippine Republic.

After the Americans defeated the First Republic, the US-instituted Philippine Legislature convened at the Ayuntamiento in Intramuros, Manila from 1907 to 1926, when it transferred to the Legislative Building just outside Intramuros. In the Legislative Building, the Senate occupied the upper floors while the House of Representatives used the lower floors.

Destroyed during the Battle of Manila of 1945, the Commonwealth Congress convened at the Old Japanese Schoolhouse at Sampaloc. Congress met at the school auditorium, with the Senate convening on evenings and the House of Representatives meeting every morning. Congress would return to the Legislative Building, which will be renamed as the Congress Building, in 1949 up to 1973 when President Marcos ruled by decree. Marcos built a new seat of a unicameral parliament at Quezon City, which would eventually be the Batasang Pambansa Complex. The parliament that will eventually be named as the Batasang Pambansa (National Legislature), first met at the Batasang Pambansa Complex in 1978.

With the overthrow of Marcos after the People Power Revolution, the bicameral Congress was restored. The House of Representatives inherited the Batasang Pambansa Complex, while the Senate returned to the Congress Building. In May 1997, the Senate moved to the newly constructed building owned by the GSIS on land reclaimed from Manila Bay at Pasay; the Congress Building was eventually transformed into the National Museum of Fine Arts.

Powers

_%2C_Republic_of_the_Philippines.svg.png)

_%2C_Congress_of_the_Philippines.svg.png)

The powers of the Congress of the Philippines may be classified as:

| General Legislative

It consists of the enactment of laws intended as a rule of conduct to govern the relation between individuals (i.e., civil laws, commercial laws, etc.) or between individuals and the state (i.e., criminal law, political law, etc.)[2] |

Implied Powers

It is essential to the effective exercise of other powers expressly granted to the assembly. |

Inherent Powers

These are the powers which though not expressly given are nevertheless exercised by the Congress as they are necessary for its existence such as:

|

Specific Legislative

It has reference to powers which the Constitution expressly and specifically directs to perform or execute. Powers enjoyed by the Congress classifiable under this category are:

|

| Executive

Powers of the Congress that are executive in nature are:

|

Supervisory

The Congress of the Philippines exercises considerable control and supervision over the administrative branch - e.g.:

|

Electoral

Considered as electoral power of the Congress of the Philippines are the Congress' power to:

|

Judicial

Constitutionally, each house has judicial powers:

|

| Miscellaneous

The other powers of Congress mandated by the Constitution are as follows:

| |||

Lawmaking

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the Philippines |

|

|

|

Constitutional commissions |

|

Related topics |

|

|

- Preparation of the bill

- The Member or the Bill Drafting Division of the Reference and Research Bureau prepares and drafts the bill upon the Member's request.

- First reading

- The bill is filed with the Bills and Index Service and the same is numbered and reproduced.

- Three days after its filing, the same is included in the Order of Business for First Reading.

- On First Reading, the Secretary General reads the title and number of the bill. The Speaker refers the bill to the appropriate Committee/s.

- Committee consideration / action

- The Committee where the bill was referred to evaluates it to determine the necessity of conducting public hearings.

- If the Committee finds it necessary to conduct public hearings, it schedules the time thereof, issues public notices and invites resource persons from the public and private sectors, the academe, and experts on the proposed legislation.

- If the Committee determines that public hearing is not needed, it schedules the bill for Committee discussion/s.

- Based on the result of the public hearings or Committee discussions, the Committee may introduce amendments, consolidate bills on the same subject matter, or propose a substitute bill. It then prepares the corresponding committee report.

- The Committee approves the Committee Report and formally transmits the same to the Plenary Affairs Bureau.

- Second reading

- The Committee Report is registered and numbered by the Bills and Index Service. It is included in the Order of Business and referred to the Committee on Rules.

- The Committee on Rules schedules the bill for consideration on Second Reading.

- On Second Reading, the Secretary General reads the number, title and text of the bill and the following takes place:

- Period of Sponsorship and Debate

- Period of Amendments

- Voting, which may be by

- viva voce

- count by tellers

- division of the House

- nominal voting

- Third reading

- The amendments, if any, are engrossed and printed copies of the bill are reproduced for Third Reading.

- The engrossed bill is included in the Calendar of Bills for Third Reading and copies of the same are distributed to all the Members three days before its Third Reading.

- On Third Reading, the Secretary General reads only the number and title of the bill.

- A roll call or nominal voting is called and a Member, if he desires, is given three minutes to explain his vote. No amendment on the bill is allowed at this stage.

- The bill is approved by an affirmative vote of a majority of the Members present.

- If the bill is disapproved, the same is transmitted to the Archives.

- Transmittal of the approved bill to the Senate

- The approved bill is transmitted to the Senate for its concurrence.

- Senate action on approved bill of the House

- The bill undergoes the same legislative process in the Senate.

- Conference committee

- A Conference Committee is constituted and is composed of Members from each House of Congress to settle, reconcile or thresh out differences or disagreements on any provision of the bill.

- The conferees are not limited to reconciling the differences in the bill but may introduce new provisions germane to the subject matter or may report out an entirely new bill on the subject.

- The Conference Committee prepares a report to be signed by all the conferees and the chairman.

- The Conference Committee Report is submitted for consideration/approval of both Houses. No amendment is allowed.

- Transmittal of the bill to the President

- Copies of the bill, signed by the Senate President and the Speaker of the House of Representatives and certified by both the Secretary of the Senate and the Secretary General of the House, are transmitted to the President.

- Presidential action on the bill

- If the bill is approved by the President, it is assigned an RA number and transmitted to the House where it originated.

- Action on approved bill

- The bill is reproduced and copies are sent to the Official Gazette Office for publication and distribution to the implementing agencies. It is then included in the annual compilation of Acts and Resolutions.

- Action on vetoed bill

- The message is included in the Order of Business. If the Congress decides to override the veto, the House and the Senate shall proceed separately to reconsider the bill or the vetoed items of the bill. If the bill or its vetoed items is passed by a vote of two-thirds of the Members of each House, such bill or items shall become a law.

Composition

Senate

|

House of Representatives

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Voting requirements

The vote requirements in the Congress of the Philippines are as follows:

| Requirement | Senate | House of Representatives | Joint session | All members |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-fifth |

|

N/A | N/A | |

| One-third | N/A |

|

N/A | N/A |

| Majority (50% +1 member) |

|

|

|

|

| ||||

| Two-thirds |

|

|

| |

|

N/A | |||

| Three-fourths | N/A | N/A | N/A |

|

In most cases, such as the approval of bills, only a majority of members present is needed; on some cases such as the election of presiding officers, a majority of all members, including vacant seats, is needed.

Latest elections

Senate

In the Philippines, the most common way to illustrate the result in a Senate election is via a tally of candidates in descending order of votes. The twelve candidates with the highest number of votes are elected.

| # | Candidate | Coalition | Party | Votes | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Cynthia Villar | HNP | Nacionalista | 25,283,727 | 53.46% | ||

| 2. | Grace Poe | Independent | 22,029,788 | 46.58% | |||

| 3. | Bong Go | HNP | PDP–Laban | 20,657,702 | 42.35% | ||

| 4. | Pia Cayetano | HNP | Nacionalista | 19,789,019 | 41.84% | ||

| 5. | Ronald dela Rosa | HNP | PDP–Laban | 19,004,225 | 40.18% | ||

| 6. | Sonny Angara | HNP | LDP | 18,161,862 | 38.40% | ||

| 7. | Lito Lapid | NPC | 16,965,464 | 35.87% | |||

| 8. | Imee Marcos | HNP | Nacionalista | 15,882,628 | 33.58% | ||

| 9. | Francis Tolentino | HNP | PDP–Laban | 15,510,026 | 32.79% | ||

| 10. | Koko Pimentel | HNP | PDP–Laban | 14,668,665 | 31.01% | ||

| 11. | Bong Revilla | HNP | Lakas | 14,624,445 | 30.92% | ||

| 12. | Nancy Binay | UNA | UNA | 14,504,936 | 30.67% | ||

| 13. | JV Ejercito | HNP | NPC | 14,313,727 | 30.26% | ||

| 14. | Bam Aquino | Otso Diretso | Liberal | 14,144,923 | 29.91% | ||

| 15. | Jinggoy Estrada | HNP | PMP | 11,359,305 | 24.02% | ||

| 16. | Mar Roxas | Otso Diretso | Liberal | 9,843,288 | 20.81% | ||

| 17. | Serge Osmeña | Independent | 9,455,202 | 19.99% | |||

| 18. | Willie Ong | Lakas | 7,616,265 | 16.12% | |||

| 19. | Dong Mangudadatu | HNP | PDP–Laban | 7,499,604 | 15.86% | ||

| 20. | Jiggy Manicad | HNP | Independent | 6,896,889 | 14.58% | ||

| 21. | Chel Diokno | Otso Diretso | Liberal | 6,342,939 | 13.41% | ||

| 22. | Juan Ponce Enrile | PMP | 5,319,298 | 11.25% | |||

| 23. | Gary Alejano | Otso Diretso | Liberal | 4,726,652 | 9.99% | ||

| 24. | Neri Colmenares | Labor Win | Makabayan | 4,683,942 | 9.90% | ||

| 25. | Samira Gutoc | Otso Diretso | Liberal | 4,345,252 | 9.19% | ||

| 26. | Romulo Macalintal | Otso Diretso | Independent | 4,007,339 | 8.47% | ||

| 27. | Erin Tañada | Otso Diretso | Liberal | 3,870,529 | 8.18% | ||

| 28. | Larry Gadon | KBL | 3,487,780 | 7.37% | |||

| 29. | Florin Hilbay | Otso Diretso | Aksyon | 2,757,879 | 5.83% | ||

| 30. | Freddie Aguilar | Independent | 2,580,230 | 5.46% | |||

| 31. | Glenn Chong | KDP | 2,534,335 | 5.36% | |||

| 32. | Raffy Alunan | Bagumbayan | 2,059,359 | 4.35% | |||

| 33. | Faisal Mangondato | KKK | Independent | 1,988,719 | 4.20% | ||

| 34. | Agnes Escudero | KKK | Independent | 1,545,985 | 3.27% | ||

| 35. | Dado Padilla | PFP | 1,095,337 | 2.32% | |||

| 36. | Ernesto Arellano | KKK, Labor Win | Independent | 937,713 | 2.30% | ||

| 37. | Allan Montaño | Labor Win | Independent | 923,419 | 2.25% | ||

| 38. | Leody de Guzman | Labor Win | PLM | 893,506 | 2.17% | ||

| 39. | Melchor Chavez | PMM | 764,473 | 2.06% | |||

| 40. | Vanjie Abejo | KKK | Independent | 656,006 | 2.00% | ||

| 41. | Toti Casiño | KDP | 580,853 | 1.97% | |||

| 42. | Abner Afuang | PMM | 559,001 | 1.92% | |||

| 43. | Shariff Albani | PMM | 496,855 | 1.87% | |||

| 44. | Dan Roleda | UNA | UNA | 469,840 | 1.80% | ||

| 45. | Ding Generoso | KKK | Independent | 449,785 | 1.75% | ||

| 46. | Lady Ann Sahidulla | KDP | 444,096 | 1.68% | |||

| 47. | Abraham Jangao | Independent | 434,697 | 1.65% | |||

| 48. | Marcelino Arias | PMM | 404,513 | 1.59% | |||

| 49. | Richard Alfajora | KKK | Independent | 404,513 | 1.57% | ||

| 50. | Sonny Matula | Labor Win | PMM | 400,339 | 1.50% | ||

| 51. | Elmer Francisco | PFP | 395,427 | 1.45% | |||

| 52. | Joan Sheelah Nalliw | KKK | Independent | 390,165 | 1.38% | ||

| 53. | Gerald Arcega | PMM | 383,749 | 1.30% | |||

| 54. | Butch Valdes | KDP | 367,851 | 1.20% | |||

| 55. | Jesus Caceres | KKK | Independent | 358,472 | 0.90% | ||

| 56. | Bernard Austria | PDSP | 347,013 | 0.70% | |||

| 57. | Jonathan Baldevarona | Independent | 310,411 | 0.67% | |||

| 58. | Emily Mallillin | KKK | Independent | 304,215 | 0.64% | ||

| 59. | Charlie Gaddi | KKK | Independent | 286,361 | 0.50% | ||

| 60. | RJ Javellana | KDP | 258,538 | 0.47% | |||

| 61. | Junbert Guigayuma | PMM | 240,306 | 0.40% | |||

| 62. | Luther Meniano | PMM | 159,774 | 0.30% | |||

| Total turnout | 47,296,442 | 74.31% | |||||

| Total votes | 361,551,157 | N/A | |||||

| Registered voters | 63,643,263 | 100.0% | |||||

| Reference: Commission on Elections sitting as the National Board of Canvassers. | |||||||

House of Representatives

A voter has two votes in the House of Representatives: one vote for a representative elected in the voter's congressional district (first-past-the-post), and one vote for a party in the party-list system (closed list), the so-called sectoral representatives; sectoral representatives shall comprise not more than 20% of the House of Representatives.

To determine the winning parties in the party-list election, a party must surpass the 2% election threshold of the national vote; usually, the party with the largest number of votes wins the maximum three seats, the rest two seats. If the number of seats of the parties that surpassed the 2% threshold is less than 20% of the total seats, the parties that won less than 2% of the vote gets one seat each until the 20% requirement is met.

| ||||||||||||||

| Party | Popular vote | Seats | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % | Swing | Entered | Up | Won[6] | % | +/− | |||||||

| PDP–Laban (Philippine Democratic Party–People's Power) | 12,653,960 | 31.23% | 127 | 94 | 82 | 26.97% | ||||||||

| Nacionalista (Nationalist Party) | 6,524,100 | 16.10% | 69 | 37 | 42 | 13.82% | ||||||||

| NPC (Nationalist People's Coalition) | 5,797,543 | 14.31% | 61 | 33 | 37 | 12.17% | ||||||||

| NUP (National Unity Party) | 3,852,909 | 9.51% | 42 | 28 | 25 | 8.22% | ||||||||

| Liberal (Liberal Party) | 2,321,759 | 5.73% | 26 | 18 | 18 | 5.92% | ||||||||

| Lakas (People Power–Christian Muslim Democrats) | 2,069,871 | 5.11% | 29 | 5 | 12 | 3.95% | ||||||||

| PFP (Federal Party of the Philippines) | 965,048 | 2.38% | 32 | 2 | 5 | 1.64% | ||||||||

| HNP (Faction of Change) | 652,318 | 1.61% | 6 | 3 | 3 | 0.99% | ||||||||

| Aksyon (Democratic Action) | 398,616 | 0.98% | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0.33% | ||||||||

| PMP (Force of the Filipino Masses) | 396,614 | 0.98% | 9 | 1 | 1 | 0.33% | ||||||||

| Bukidnon Paglaum (Hope for Bukidnon) | 335,628 | 0.83% | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0.66% | ||||||||

| PDDS (Noble Blood Association of Federalists) | 259,423 | 0.64% | 31 | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | ||||||||

| LDP (Struggle of Democratic Filipinos) | 252,806 | 0.62% | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0.66% | ||||||||

| UNA (United Nationalist Alliance) | 232,657 | 0.57% | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | ||||||||

| HTL (Party of the People of the City) | 197,024 | 0.49% | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.33% | ||||||||

| PPP (Palawan's Party of Change) | 185,810 | 0.46% | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.66% | ||||||||

| Bileg (Ilocano Power) | 158,523 | 0.39% | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.33% | ||||||||

| PRP (People's Reform Party) | 138,014 | 0.34% | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0.33% | ||||||||

| Unang Sigaw (First Cry of Nueva Ecija) | 120,674 | 0.30% | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | ||||||||

| KDP (Union of Democratic Filipinos) | 116,453 | 0.29% | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | ||||||||

| Asenso Abrenio (Progress for Abrenians) | 115,865 | 0.29% | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.33% | ||||||||

| Kambilan (Shield and Fellowship of Kapampangans) | 107,078 | 0.26% | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | ||||||||

| Padayon Pilipino (Onward Filipinos) | 98,450 | 0.24% | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | ||||||||

| Asenso Manileño (Progress for Manilans) | 84,656 | 0.21% | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0.66% | ||||||||

| Kusog Bicolandia (Force of Bicol) | 82,832 | 0.20% | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | ||||||||

| CDP (Centrist Democratic Party of the Philippines) | 81,741 | 0.20% | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.33% | ||||||||

| Navoteño (Navotas Party) | 80,265 | 0.20% | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.33% | ||||||||

| KABAKA (Partner of the Nation for Progress) | 65,836 | 0.16% | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.33% | ||||||||

| PDSP (Philippine Social Democratic Party) | 56,223 | 0.14% | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | ||||||||

| Bagumbayan (New Nation-Volunteers for a New Philippines) | 33,731 | 0.08% | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | ||||||||

| KBL (New Society Movement) | 33,594 | 0.08% | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | ||||||||

| AZAP (Forward Zamboanga Party) | 28,605 | 0.07% | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | ||||||||

| WPP (Labor Party Philippines) | 9,718 | 0.02% | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | ||||||||

| DPP (Democratic Party of the Philippines) | 1,110 | 0.00% | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | ||||||||

| HSS (Surigao Sur Party) | 816 | 0.00% | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | ||||||||

| PGRP (Philippine Green Republican Party) | 701 | 0.00% | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | ||||||||

| Independent | 2,014,211 | 4.97% | 143 | 1 | 2 | 0.66% | ||||||||

| TotalA | 40,524,366 | 100% | N/A | 627 | 238 | 243 | 79.9% | |||||||

| Valid votes | 40,524,366 | 86.90% | ||||||||||||

| Invalid votes | 6,106,908 | 13.10% | ||||||||||||

| Turnout | 46,631,274 | 75.40% | ||||||||||||

| Registered voters (without overseas voters) | 61,843,771 | 100% | ||||||||||||

Notes:

^ The congressional districts for General Santos and both Southern Leyte's districts were supposedly done later in 2019, as these were approved after the ballots were printed. Elections for South Cotabato as two districts, where General Santos is included in the 1st district, and Southern Leyte's lone district, still proceeded, but all votes were declared as stray. However, the Supreme Court ruled that the result of the election for South Cotabato's 1st district, stood, ordering the commission to proclaim Shirlyn L. Bañas-Nograles as the winner.[7] The commission then decided that the winner in Southern Leyte's congressional election, Roger Mercado, be proclaimed as well.[8]

See also

Notes

- These are 3 parties that have 1 to 3 members each.

- These include 51 parties that have 1 to 3 members each.

References

- "Article VI: THE LEGISLATIVE DEPARTMENT". Philippines Official Gazette. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- "The Legislative Branch". Philippines Official Gazette. Philippines Official Gazette. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- "The City Council of Manila". Manila Standard. June 24, 2002. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- Elizalde, María Dolores (September 2013). "The Philippines at the Cortes de Cádiz". Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints. 61 (3): 331–361.

- Commission on Elections

- "Number of Elected Candidates by Party Affiliation Per Elective Position, by Sex" (PDF). COMELEC.gov.ph. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- Supreme Court en Banc (September 10, 2019). "G.R. No. 246328 - Vice Mayor Shirlyn L. Bañas-Nograles, et al. Vs. Commission on Elections". Supreme Court of the Philippines. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- Arnaiz, Jani (December 17, 2019). "Rep. Mercado proclaimed as Congressman for lone District of Southern Leyte". The Reporter. Archived from the original on December 25, 2019. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

Sources

- Ramirez, Efren V. and Lee, Jr., German G., The New Philippine Constitution. Cebu City: 1987: pp. 142–173.

- Article VI of the 1987 Philippine Constitution

- How a Bill becomes a Law

- Legislative History

- Your Legislature