Armed Forces of the Philippines

The Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP; Filipino: Sandatahang Lakas ng Pilipinas; Spanish: Fuerzas Armadas de Filipinas) are the military forces of the Philippines. It consists of the three main service branches; the Army, the Navy (including the Marine Corps) and the Air Force. The President of the Philippines is the Commander-in-Chief of the AFP and forms military policy with the Department of National Defense, an executive department acting as the principal organ by which military policy is carried out, while the Chief of Staff is the overall commander and the highest-ranking officer in the AFP. The Philippine Coast Guard also serves as an attached service of the AFP in wartime. Military service is entirely voluntary.[5]

| Armed Forces of the Philippines | |

|---|---|

| Sandatahang Lakas ng Pilipinas Fuerzas Armadas de Filipinas | |

Marks of the AFP's service branches | |

Emblem of the Armed Forces of the Philippines | |

| Founded | December 21, 1935 |

| Service branches | |

| Headquarters | Camp Aguinaldo, Quezon City, National Capital Region |

| Website | www |

| Leadership | |

| Commander-in-Chief | |

| Secretary of National Defense | |

| Chairman of the Joint Chiefs | |

| Manpower | |

| Military age | 18–56 years old |

| Conscription | None enforced, optional through ROTC |

| Available for military service | 25,614,135 (2010 est.)[1] males, age 18–56, 25,035,061 (2010 est.)[1] females, age 18–56 |

| Fit for military service | 20,142,940 (2010 est.)[2] males, age 18–56, 21,427,792 (2010 est.)[2] females, age 18–56 |

| Active personnel | 125,000 (2019)[3] |

| Reserve personnel | 180,000 (2019)[3] |

| Expenditures | |

| Budget | ₱186 billion (2020)[4] (US$3.69 billion) |

| Percent of GDP | 0.9% |

| Industry | |

| Domestic suppliers | Government Arsenal Steelcraft Industrial and Development Corp. Ferfrans Armscor Joavi Philippines Corp. |

| Foreign suppliers | |

| Related articles | |

| History |

|

| Ranks | Military ranks of the Philippines |

Leadership

.svg.png)

AFP Chain of Command

| Position | Photograph | Name | Service |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chief of Staff |  | General Gilbert I. Gapay [6] | Philippine Army |

| Vice Chief of Staff |  | Vice Admiral Gaudencio C. Collado Jr.[7][8] | Philippine Navy |

| Deputy Chief of Staff | Lieutenant General Antonio Ramon A. Lim | Philippine Air Force | |

| Commanding General of the Philippine Army | Lieutenant General Cirilito E. Sobejana | Philippine Army | |

| Flag Officer in-Command |  | Vice Admiral Giovanni Carlo J. Bacordo [9] | Philippine Navy |

| Commanding General of the Philippine Air Force |  | Lieutenant General Allen T. Paredes [12][13][14] | Philippine Air Force |

| Commandant of the Philippine Marine Corps (CMDT-PMC) | Major General Nathaniel Y. Casem [15] | Philippine Marine Corps | |

| Sergeant Major of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (SMAFP) | First chief master sergeant Lito A. Tompayogan [16] | Philippine Army |

History

Pre-Hispanic Philippines maintained local militia groups under the barangay system. Reporting to the datu, these groups, aside from maintaining order in their communities, also served as their defense forces. With the arrival of Islam, the system of defense forces in the Mindanao region's sultanates under Muslim control mirrored those other existing sultanates in the region. These local warriors who were in the service of the Sultan were also responsible to qualified male citizens appointed by him.

During the Spanish colonial period, the Spanish Army was responsible for the defense and general order of the archipelago in the land, while the Spanish Navy conducts maritime policing in the seas as well as providing naval logistics to the Army. The Guardia Civil took police duties and maintaining public order in villages and towns. In the early years of Spanish colonial era, most of the formations of the army were composed of conquistadors backed with native auxiliaries. By the 18th and 19th Centuries, line infantry and cavalry formations were created composed of mixed Spanish and Filipino personnel, as well as volunteer battalions composed of all-Filipino volunteers during the later half of the 19th Century. Units from other colonies were also levied to augment the existing formations in the Philippines. Almost all of the formations of the Spanish Army in the archipelago participated in the local religious uprisings between 17th and 19th Centuries, and in the Philippine Revolution in 1896 fighting against the revolutionary forces. At the peak of the revolution, some Filipinos and a few Spaniards in the Spanish Army, Guardia Civil, and Navy defected to the Philippine Revolutionary Army.

The Spanish cession of the Philippines in the 1898 Treaty of Paris put the independence of the newly declared Southeast Asian republic in grave danger. The revolutionaries were fighting desperately as the American forces already landed in other islands and had taken over towns and villages. The Americans established the Philippine Constabulary in 1901 manned by Filipino fighters and used against Gen. Aguinaldo who was later captured.

On April 9, 2002, Philippine President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo proclaimed that the Philippine–American War had ended on April 16, 1902 with the surrender of General Miguel Malvar.[17]

Since the beginning of American rule in the Philippines, the United States Army had taken the responsibility for the defense of the country in the land, and the United States Navy in the seas until the passage of the National Defense Act of 1935 which called for a separate defense force for the Philippines.

Creation and World War II

In accordance with the National Defense Act of 1935, the Armed Forces of the Philippines was officially established on December 21, 1935, when the act entered into force.[18] Retired U.S. General Douglas MacArthur was asked to supervise its foundation and training. MacArthur accepted the offer and became a Field Marshal of the Philippines, a rank no other person has since held.[19] Jean MacArthur, his wife, found the situation amusing and remarked that her husband had gone from holding the highest rank in the United States Army to holding the highest rank in a non-existent army. President Quezon officially conferred the title of Field Marshal on MacArthur in a ceremony at Malacañan Palace on August 24, 1936 when he appeared with a gold marshal's baton and a unique uniform.[20]

The Army of the Philippines included naval and air assets directly reporting to Army headquarters, and the Philippine Constabulary, later part of the ground forces proper as a division. In 1938 the Constabulary Division was separated from the army and reorganized into a national police force.[21][22]

MacArthur expanded the Army of the Philippines with the revival of the Navy in 1940 and the formation of the Philippine Army Air Corps (formerly the Philippine Constabulary Air Corps), but they were not ready for combat at the start of the Pacific War in December 1941 and unable to defeat the 1941–42 Japanese invasion of the Philippines.

In 1940–41, most soldiers of the Philippine military were incorporated in the U.S. Army Forces Far East (USAFFE), with MacArthur appointed as its commander. USAFFE made its last stand on Corregidor Island, after which Japanese forces were able to force all remaining Filipino and American troops to surrender. The establishment of the general headquarters of the Philippine Commonwealth Army are military station went to the province during occupation. Those who survived the invasion but escaped from the Japanese formed the basis of recognized guerrilla units and ongoing local military force of the Philippine Commonwealth Army that continued the fighting against the enemy all over the islands. The Philippine Constabulary went on active service under the Armed Forces of the Philippines during liberation. After Japan was defeated in World War II, the Philippines gained its independence in 1946. (This was its second independence after the Philippine Declaration of Independence in 1898). In 1947 the modern AFP first emerged with the upgrade of the PAAC to the Philippine Air Force.

After independence

During the Korean War from 1951 to 1953, the Philippines sent various AFP battalions, known as the Philippine Expeditionary Forces to Korea (PEFTOK) to fight as part of the US-led United Nations Command in liberating South Korea from the invading North Korean troops. At the same time the armed forces, including the established Marine company under the PN, fought against Communist elements of the Hukbalahap (by then the Bagong Hukbong Bayan, the Philippine counterpart of the PLA) in Central Luzon, two Southern Tagalog provinces and several Visayan provinces, with great successes.

In 1966, an AFP battalion was also sent into South Vietnam during the Vietnam War to ameliorate the economic and social conditions of its people there. AFP units were also sent at the same time to the Spratly Islands.

1963 would see the first women join the ranks of the armed forces with the raising of the Women's Auxiliary Corps.

Upon the declaration of Martial Law in 1972, then-President Ferdinand Marcos used the AFP, through the regime's secret police force, the National Intelligence and Security Authority, to arrest, and to contain his political opponents. However, Marcos – as Commander in Chief – did modernization efforts for the AFP by instituting a series of self-reliance programs to enable it to construct its own weapons, warplanes, tanks, ships and aircraft locally instead of buying from foreign sources. A missile development program known as the "Sta. Barbara project" was initiated by the AFP and missiles were successfully tested, but the project was discontinued after the Marcos administration.[23]

In 1981, when Marcos' trusted military officer, General Fabian Ver became the AFP chief of staff, favoritism was believed to be attached to the military organization due to the fact that the general only placed his favorites in most sensitive positions, it did not dismay qualified officers. Marcos would like to make sure who is fit for the job. Ver and Marcos also extended the tour of duty of those military officers who should have been effectively retired, to the dismay also of the younger officers. Consequently, discontent in the AFP ensued.

The AFP also at that time, waged a military campaign against the secessionist Moro National Liberation Front in the island of Mindanao and New People's Army units under the Communist Party of the Philippines nationwide, growing to a 200,000 strong force.

In 1986, a faction of AFP headed by then Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile and AFP vice-chief of staff Lt. General Fidel V. Ramos took a stand against Marcos, ushering in the bloodless People Power Revolution that removed Marcos from power and installed Corazon Aquino as the new president of the Philippines.

During Aquino's term, most of the military units remained loyal to her as she dealt with various coup attempts against her by other military factions that remained loyal to the former dictator and those military officers who helped her to assume power. The 1989 coup attempt, the bloodiest of all coup attempts against her was crushed with US help. The AFP, during her term also launched a massive campaign against the CPP-NPA after a brief hiatus and also against the MNLF in the south.

In 1991, the major services of the AFP was reduced from four to three, when the Philippine Constabulary or PC, an AFP major service tasked to enforce the law and to curb criminality, was formally merged with the country's Integrated National Police, a national police force on the cities and municipalities in the country attached to the PC to become the Philippine National Police, thus removing it from AFP control and it was civilianized by a law passed by Congress, therefore becoming under the Department of the Interior and Local Government as a result.

In 2000, then President Joseph Estrada ordered the AFP to launch an "All-Out war" against the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, a breakaway group of the MNLF that wants to proclaim Mindanao an independent state.

In 2001, Estrada was removed from power in the two-day Edsa Dos People Power revolt, in which the AFP played a key role. The revolution installed then Vice-President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo as president.

Since 2001, the Armed Forces of the Philippines has been active in supporting the War on terror and has been attacking terrorist groups in Mindanao ever since. In 2012, the AFP Chief of Staff said that there had been no increase in the number of soldiers over a long period, and that the military aimed to hire 30,000 troops in three years.[24]

In 2013, the AFP managed to stall the attacks of the Moro National Liberation Front in the Zamboanga City crisis as they launch an attack to proclaim the independence of the Bangsamoro Republik. In 2016, the AFP clashed with the Maute group on Butig on February and on November of 2016. In 2017, The AFP also clashed with ISIS Militants in Marawi, calling President Duterte to declare Martial Law under Proclamation No. 216.

Modernization

Republic Act No. 7898, approved on February 23, 1995, declared it the policy of the State to modernize the AFP to a level where it can effectively and fully perform its constitutional mandate to uphold the sovereignty and preserve the patrimony of the Republic of the Philippines, and mandated specific actions to be taken to achieve this end.[25] Republic Act No. 10349, approved on December 11, 2012, amended RA7898 to establish a revised AFP modernization program.[26] The act include new provision for the acquisition of equipment for all the branches of AFP.

Organization and branches

The 1987 Philippine Constitution placed the AFP under the control of a civilian, the President of the Philippines, who acts as its Commander-in-Chief. All of its branches are part of the Department of National Defense, which is headed by the Secretary of National Defense.

The AFP has three major services:[27]

These three major services are unified under a Chairman of the Joint Chiefs who normally holds the rank of General/Admiral. He is assisted by:

- The Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs

- The Chief of the Joint Staff

Both normally holding the rank of Lieutenant General/Vice Admiral.

Each of the three major branches are headed by an officer with the following titles:

- Chief of the Army (Lieutenant General)

- Chief of the Navy (Vice Admiral)

- Chief of the Air Force (Lieutenant General)

- AFP Inspector General (Lieutenant General/Vice Admiral)

- Joint Forces Commander, Unified Command (Lieutenant General/Vice Admiral)

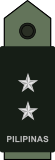

Meanwhile, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs is also assisted by the following office holders carry the rank of Major General/Rear Admiral:

- The Commandant of the Philippine Marine Corps

- The Deputy Chief of Joint Staff for Personnel

- The Deputy Chief of Joint Staff for Intelligence

- The Deputy Chief of Joint Staff for Operations, Organization & Training

- The Deputy Chief of Joint Staff for Logistics

- The Deputy Chief of Joint Staff for Plans

- The Deputy Chief of Joint Staff for Communications, Electronics and Information Systems Service

- The Deputy Chief of Joint Staff for Civil-Military Operations

- The Deputy Chief of Joint Staff for Education and Training

- The Deputy Chief of Joint Staff for Retirees and Reservists Affairs

- Army Division Commanders

- Naval Command Commanders

- Air Command Commanders

In June 19, 2020, under the DND Order no. 174, the AFP had major changes in renaming its positions in high ranking officials, such as: [28]

- Chief of Staff of the AFP - Chairman of the Joint Chiefs

- Vice Chief of Staff of the AFP - Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs

- Deputy Chief of Staff of the AFP - Chief of the Joint Staff

- Commander, Unified Command - Joint Forces Commander, Unified Command

- Deputy Chief of Staff for (functional area) (J-staff) - Deputy Chief of Joint Staff for (functional area)

- Commanding General of the Philippine Army - Chief of the Army

- Flag Officer in-Command - Chief of the Navy

- Commanding General of the Philippine Air Force - Chief of the Air Force

Former branches

The Philippine Constabulary (PC) was a gendarmerie type para-military police force of the Philippines established in 1901 by the United States-appointed administrative authority, replacing the Guardia Civil of the Spanish colonial regime. On December 13, 1990, Republic Act No. 6975 was approved, organizing the Philippine National Police (PNP) consisting of the members of the Integrated National Police (INP) and the officers and enlisted personnel of the PC. Upon the effectivity of that Act, the PC ceased to be a major service of the Armed Forces of the Philippines and the INP ceased to be the national police and civil defense force.[29] On January 29, 1991, the PC and the INP were formally retired and the PNP was activated in their place.[30]

Unified commands

Units from these three services may be assigned to one of six "Unified Commands" led by each Joint Forces Commander, Unified Command; consisting of different branches from the three branches of the AFP, which are multi-service, regional entities:[31]

Former Unified & Wide Support Commands

- National Capital Region Command (NCRCOM)

- National Development Support Command (NADESCOM)

- Southern Command (SOUTHCOM)

- National Capital Region Defense Command (NCRDC)

- Central Luzon Command (CELCOM)

- Home Defense Command (HDC)

- Internal Defense Command

AFP-wide service support and separate units

Several service-wide support services and separate units report directly to the AFP General Headquarters (AFP GHQ), these include:

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

- AFP Education, Training, and Doctrine Command under which is the

- Armed Forces of the Philippines Reserve Command (AFPRESCOM)

- Intelligence Service, Armed Forces of the Philippines (ISAFP)

- AFP Health Service Command under which is the

- Armed Forces of the Philippines Commissary and Exchange Service (AFPCES)

- Communications, Electronics and Information System Service, Armed Forces of the Philippines (CEISSAFP)

- Civil Relations Service, Armed Forces of the Philippines (CRSAFP)

- AFP Joint Task Force-National Capital Region (AFP JTF-NCR) – Replaced the deactivated NCR Commands

- AFP Doctrine Development Center (AFPDDC)

Philippine Defense Reform

In October 1999, the Joint Defense Assessment (JDA) began as a policy level discussion between the Philippine Secretary of National Defense and the US Secretary of Defense. An initial JDA report in 2001 provided an objective evaluation of Philippine defense capability. During a May 2003 state visit to Washington DC, President Arroyo requested U.S. assistance in conducting a strategic assessment of the Philippine defense system. This led to a follow-up JDA and formulation of recommendations addressing deficiencies found in the Philippine defense structure.[32]

The results of the 2003 JDA were devastating. The JDA findings revealed that the AFP was only partially capable of performing its most critical missions. Moreover, the results pointed overwhelmingly toward institutional and strategic deficiencies as being the root cause of most of the shortcomings. A common thread in all: the lack of strategy-based planning that would focus DND/AFP on addressing priority threats and link capability requirements with the acquisition process.

Specifically, the 2003 JDA revealed critical deficiencies in the following specific areas:[33]

- Systemic approach to policy planning

- Personnel management and leadership

- Defense expenditures and budgeting

- Acquisition

- Supply and maintenance

- Quality assurance for existing industrial base

- Infrastructure support

During a reciprocal visit to the Philippines in October 2003 by U.S. President Bush, he and President Arroyo issued a joint statement expressing their commitment to embark upon a multi-year plan to implement the JDA recommendations. The Philippine Defense Reform (PDR) Program is the result of that agreement.

The JDA specifically identified 65 key areas and 207 ancillary areas of concern. These were reduced to ten broad-based and inter-related recommendations that later became the basis for what became known as the PDR Priority Programs. The ten are:[34] 1. Multi-Year Defense Planning System (MYDPS) 2. Improve Intelligence, Operations, and Training Capacities 3. Improve Logistics Capacity 4. Professional Development Program 5. Improve Personnel Management System 6. Multi-year Capabilities Upgrade Program (CUP) 7. Optimization of Defense Budget and Improvement of Management Controls 8. Centrally Managed Defense Acquisition System Manned by a Professional Workforce 9. Development of Strategic Communication Capability 10. Information Management Development Program

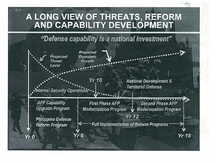

From the perspective of the Philippine Department of National Defense (DND), the framework for reforms is based on an environment of increasing economic prowess and a gradually decreasing threat level over time, and seeks to make the following improvements:[35] 1. Address AFP capability gaps to enable the AFP to effectively fulfill its mission. 2. Implement capability for seamless interoperability by developing proficiency in the conduct of joint operations, eliminating crisis handling by individual major services as done previously. 3. improve effectiveness of internal security operations. 4. Enhance capability to counter terrorism and other transnational threats. 5. Provide sustainment and/or long-term viability of acquired capabilities. 6. Improve cost-effectiveness of operations. 7. Improve accountability and transparency in the DND. 8. Increase professionalism in the AFP through reforms in areas such as promotions, assignments, and training. 9. Increase involvement of AFP in the peace process.

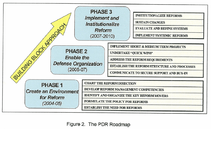

According to the goals stated in the Philippines Defense Reform Handbook: "The PDR serves as the overall framework to re-engineer our systems and re-tool our personnel."[36] The Philippine Defense Reform follows a three-step implementation plan:[37] 1. Creating the environment for reform (2004–2005); 2. Enabling the defense establishment (2005–2007); 3. Implementing and institutionalizing reform (2007–2010).

On September 23, 2003, President Arroyo issued Executive Order 240, streamlining procedures for defense contracts for the expeditious implementation of defense projects and the speedy response to security threats while promoting transparency, impartiality, and accountability in government transactions. Executive Order 240, creating the Office of the Undersecretary of Internal Control in the DND, mandated in part to institutionalize reforms in the procurement and fund disbursement systems in the AFP and the DND.[38] On November 30, 2005, the Secretary of National Defense issued Department Order No. 82 (DO 82), creating the PDR Board and formalizing the reform organizational set-up between the DND and the AFP and defining workflow and decision-making processes.[39]

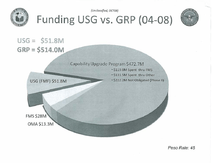

The PDR is jointly funded by the U.S. and R.P. governments. from 2004 to 2008, funding amounted to $51.8 million from the U.S. and $514.0 million from the RP.[40] Initial planning assumptioned that the 18-year span of reform would encompass a period of steady rise in economic growth coupled with equally steady decline in the military threat from terrorists and separatists. Neither of these projections have proven accurate. As of 2010, at the six-year mark of PDR, the Philippine economy was internally strong, but suffering during a period of recession that crippled Philippine purchasing power. Worse, the threat situation in the Philippines had not improved significantly, or as in the case of the Sulu Archipelago, was deteriorating.[41]

During the Arroyo presidency, deliberate 'Rolodexing' of senior leadership within the DND and AFP constantly put U.S. PDR advocates in a position of re-winning previously won points and positions, and gave U.S. observers a 'two steps forward, one step back' impression of the program. As of 2010, U.S. observers were uncertain whether Arroyo's successor, Benigno Aquino III, chosen in Philippine Presidential elections on May 10, 2010, will continue the tradition of rapid turnover of senior leadership.[42]

U.S. observers have reported that overall progress of the PDR is unmistakable and has clearly struck a wider swath of the Philippine defense establishment than originally hoped. However, they see some troubling signs that the depth of the PDR's impact may not be as significant as originally desired. For example, the Philippine legislature continues to significantly underfund the DND and AFP, currently at.9 percent of GDP, compared to an average of 2 percent worldwide, and a 4 percent outlay by the U.S. Even with full implementation of all the PDR's programs and recommendations, the defense establishment would not be able to sustain itself at current funding levels. While this can be made up by future outlays, as of 2010 observers see no outward sign the legislature is planning to do so.[42] One U.S. observer likened PDR process to the progress of a Jeepney on a busy Manila avenue—explaining, "a Jeepney moves at its own pace, stops unexpectedly, frequently changes passengers, moves inexplicably and abruptly right and left in traffic, but eventually arrives safely."[43] President Aquino has promised to implement the PDR program.[44] As of 9 March 2011, a major Philippine news organization tracking performance on his promises evaluated that one as "To Be Determined."[45]

The Mutual Defense Treaty between the Philippines and the United States has not been updated since its signing in 1951. As of 2013, discussions were underway for a formal U.S.-Philippine Framework Agreement detail how U.S. forces would be able to "operate on Philippine military bases and in Philippine territorial waters to help build Philippine military capacity in maritime security and maritime domain awareness."[46] In particular, this Framework Agreement would which would increase rotational presence of American forces in the Philippines.[47]

Longstanding treaties, such as the aforementioned 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) of 1982,[48] are of great importance to the Philippines in supporting maritime security in particular; respectively, their legally binding nature provides long-term effectiveness for mutual defense cooperation and for the development of the Philippine maritime and archipelagic domain.

Philippine defense operations are supported in part through U.S. Section 1206 ($102.3 million) and 1207 ($16.02 million) funds. These funds are aimed at carrying out security, counterterrorism training and rule of law programs.[49] Overall, the United States is increasing U.S. funding for military education and training programs in Southeast Asia. The most recent U.S. Department of Defense budget for the region includes $90 million for programs, which is a 50 percent increased from four years ago.[50]

Handling threats

In 2007, The Jamestown Foundation, a US-based think tank, reported that the AFP was one of the weakest military forces in Southeast Asia, saying that as the country's primary security threats are land-based, the Army has received priority funding, and that the operational effectiveness of the Philippine Navy (PN) and Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) has suffered accordingly, leaving the country's sea lanes largely unprotected.[51] In 2008, The Irrawaddy reported a statement by General Alexander B. Yano, then Chief of Staff of the AFP, that the Philippine military cannot fully defend the country from external threats due to a lack of weapons and a preoccupation with crushing the long-running communist and Muslim insurgencies. Yano went on to say that a more ambitious modernization of the ill-equipped navy and air force to better guard the country from external threats will have to wait, saying, "To be very frank with you, our capability as far as these aspects are concerned is a little deficient," and "We cannot really defend all these areas because of a lack of equipment."

Corruption within the higher ranks are believed to be one of the main reasons why modernization of the armed forces has remained stagnant for decades.[52]

As reported by The Philippine Star in an op-ed piece, the Commission on Audit said in its 2010 audit report for the Philippine Air Force (PAF) that with only 31 aging airplanes and 54 helicopters, the PAF "virtually has a non-existent air deterrent capability" and is "ill-equipped to be operationally responsive to national security and development."[53]

Since 1951, a Mutual Defense Treaty has been in effect between the Republic of the Philippines and the United States.[52][54]

The country is prone to transnational crime, maritime territorial disputes, environmental degradation and disasters. Transnational crimes include international terrorism, drug trafficking, small arms trafficking. Environmental degradation consists of marine resource exploitation and pollution. Disasters include typhoons and floods.

The Philippines faces technical and geospatial challenges in handling threats to maritime surveillance operations and external defense. Having the eighth longest coastline (36,000 km) in the world,[55] the country is subject to porous borders and coastlines, which place constraints on the acquisition of long-range radar systems, which require multilateral assistance due to limited defense funds. Additionally, the production, development, procurement and servicing of satellite technology is deemed as cost prohibitive.

National policies

Recent national policies have shifted the strategic direction of the AFP towards external, territorial defense as opposed to previous, internal foci. Some of the challenges with this change in strategic direction include the uneven distribution of maritime security resources among territorial, transnational, environmental, and humanitarian assistance and disaster response (HADR) conflicts.[56] For example, Philippine Executive Order 57, signed in 2011 by President Benigno Aquino III, established a central inter-agency mechanism for enhancing governance in the country's maritime domain.[57] Between 1995 and 2019, the AFP Reserve Manpower in the Philippines totaled 741,937 and 4,384,936 ROTC Cadets.[58] Out of the 700,00+ reservists; 93,062 are (ready reserve) and 610,586 are (standby reserve).[59] There are a total of 20,451 with the affiliated reserve units.[59]

Conflicts over responsibility for maritime surveillance between armed forces continue to underscore the numerous challenges that the TBA faces. For example, following the expulsion of Ferdinand Marcos from the Philippines in 1986, the Philippine Coast Guard separated from the Philippine Navy, resulting in an uneven distribution of resources and jurisdictional confusion.[60]

Recognition and achievements

The Philippine Army shooting team was the overall champion in a two-week competition held in Australia, 2013.[61] The Philippine Army shooting team won 14 gold medals, 50 silver medals and two bronze medals in Australian Army Skills at the Arms Meeting (AASAM) 2014.[62] The 7th Philippine Contingent peacekeepers to the Golan Heights were awarded the prestigious United Nations Service Medal for the performance of their mission.[63]

Ranks

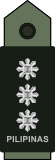

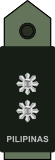

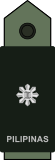

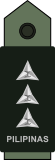

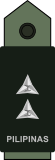

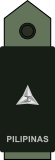

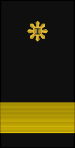

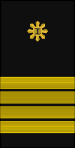

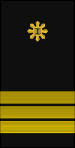

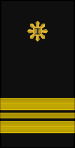

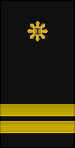

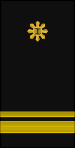

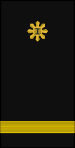

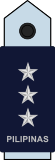

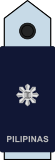

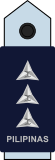

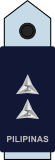

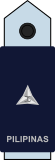

The officer ranks are as follows:[64][65]

| Equivalent NATO code | OF-10 | OF-9 | OF-8 | OF-7 | OF-6 | OF-5 | OF-4 | OF-3 | OF-2 | OF-1 | OF(D) and student officer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(Edit) |

No equivalent |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Unknown | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

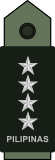

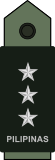

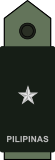

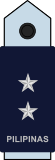

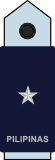

| General | Lieutenant General |

Major General |

Brigadier General |

Colonel | Lieutenant Colonel |

Major | Captain | First Lieutenant |

Second Lieutenant | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

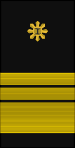

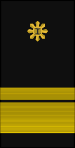

(Edit) |

No equivalent |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No equivalent | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

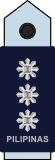

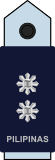

| Admiral | Vice Admiral | Rear Admiral | Commodore | Captain | Commander | Lieutenant Commander | Lieutenant | Lieutenant (junior grade) | Ensign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(Edit) |

No equivalent |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General | Lieutenant General | Major General | Brigadier General | Colonel | Lieutenant Colonel | Major | Captain | First Lieutenant | Second Lieutenant | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Equivalent NATO code | OF-10 | OF-9 | OF-8 | OF-7 | OF-6 | OF-5 | OF-4 | OF-3 | OF-2 | OF-1 | OF(D) and student officer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

These ranks, heavily inspired by those of the United States Armed Forces, are officially used in the Philippine Army, Air Force and Marine Corps. The ranks are more frequently referred and addressed in English rather than in Spanish or Tagalog/Filipino, since English is the working language within the Armed Forces.

The ranks in the Philippine Navy are similar to the US Navy ranks, the only difference is the rank of Commodore in the Philippine Navy is equivalent to the Lower Half Rear Admiral of the US Navy.

The alternative style of address for the ranks of lieutenant junior grade, lieutenant senior grade, second lieutenant, and first lieutenant are simply lieutenant in English, or tenyente or teniente in Tagalog and Spanish, respectively.

The ranks of enlisted personnel in Filipino are the same as their U.S. counterparts, with some differences. Except in the Marine Corps, never used are the ranks of specialist, sergeant first class, and first sergeant. Lance corporal, gunnery sergeant, and master gunnery sergeant are also never used by the Philippine Marine Corps, whose ranks are the same as the Army's. Additionally, sergeant majors in the AFP are only appointments for senior ranked non-commissioned officers (NCOs) rather than ranks, examples of such appointments being the Command Sergeant Major, AFP (held by a first chief master sergeant or a first master chief petty officer) and the Command Master Chief Petty Officer, Philippine Navy (held by an either MCPO or CMS or a SCPO or SMS).

In the Philippine Navy, they also use enlisted ranks which come from the U.S. Navy with their specialization, e.g. "Master Chief and Boatswain's mate Juan Dela Cruz, PN" (Philippine Navy).

In effect, the AFP uses the pre-1955 US military enlisted ranks, with several changes, especially in the Navy and in the senior NCO ranks.

There are no warrant officers in between officer ranks and enlisted ranks.

The uniqueness of Philippine military ranks can be seen in the current highest ranks of first chief master sergeant (for the Army, Marine Corps and Air Force) and first master chief petty officer (for the Navy), both created in 2004, and since then have become the highest enlisted rank of precedence. Prior, first chief sergeant and master chief petty officer were the highest enlisted ranks and rates, the former being the highest rank of precedence for Army, Air Force and Marine NCOs. Today only the rank of first master chief petty officer is unused, but the rank of first chief master sergeant is now being applied.

Five-star rank

_in_full_Battle_Dress_Uniform_(BDU).jpg)

President Ferdinand Marcos, who acted also as national defense secretary (from 1965–1967 and 1971–1972), issued an order conferring the five-star officer rank to the President of the Philippines, making himself as its first rank holder. Since then, the rank of five-star general/admiral became an honorary rank of the commander-in-chief of the armed forces whenever a new president assumes office for a six-year term, thus making the President the most senior military official.[66]

The only career military officer who reached the rank of five-star general/admiral de jure is President Fidel V. Ramos (USMA 1950) (president from 1992–1998) who rose from second lieutenant up to commander-in-chief of the armed forces.[67]

General of the Army Douglas MacArthur was also made Field Marshal of the Philippine Army with five-star rank in 1938, the only person to hold that rank. Emilio Aguinaldo, the first President of the Philippines, holds an equivalent of five-star general under the title Generalissimo and Minister/Field Marshal as the first commander-in-chief of the AFP.

The position is honorary and may be granted to any military officer, especially generals or admirals who had significant contributions and showed heroism, only in times of war and national defense concerns and emergencies. The highest peacetime rank is that of four-star general which is being held only by the AFP Chief of Staff. However, no law specifically establishes the rank of five-star general in the Armed Forces of the Philippines unlike in the United States and other countries.

Rank insignia

The AFP, like the military forces of Singapore and Indonesia, uses unitary rank insignia for enlisted personnel, in the form of raised chevrons increasing by seniority, save for the Philippine Air Force which uses inverted chevrons from Airman 2nd Class onward only since recently.[68] In the Philippine Navy these are supplemented by rating insignia by specialty, similar to the United States Navy. Like the British and Spanish armed services, however, senior ranked NCOs (especially in the Philippine Navy) also wear shoulder rank insignia only on the mess, semi-dress and dress uniforms, and in some cases even collar insignia. Like the US military all NCOs wear sleeve stripes to denote years of service in the enlisted ranks. Sleeve insignia for enlisted personnel in the Army and the Navy are similar but are different from those used in the US while those in the Marine Corps mirror its US counterpart but with special symbols from Master Sergeants onward (adopted in the early 2000s).

Officer ranks in the AFP are inspired by revolutionary insignia used by the Philippine Army after the 1898 declaration of independence. These are unitary rank insignia used in the every day, combat, duty and technical uniforms both on shoulders and collars (the latter in the khaki uniforms of the Navy), but in the semi-dress, dress and mess uniforms are different: The Army, Air Force and Marine Corps use unitary rank insignia on the shoulder board but the Navy uses the very same rank insignia format as in the US Navy except for the star (for Ensigns to Captains) in almost all officer uniforms and all general officer and flag officer shoulder boards in the full dress uniform are in gold colored backgrounds with the rank insignia and the AFP seal (the star arrangement is the same in the Army, Air Force and Marines but is different in the Navy). The Navy uses sleeve insignia only on its dress blue uniforms. Lieutenants and Captains wear 1 to 3 triangles (and Navy Ensigns and Lieutenants (junior and senior grades) in their working, duty and combat uniforms) while Majors, Lieutenant Colonels and Colonels wear 1, 2, and 3 suns (both triangles and suns have the ancient baybayin letter ka (K) in the center) as well as Navy superior officers (Lieutenant Commanders, Commanders and Captains) in their working, duty and combat uniforms respectively.

Gallery

- Armed Forces of the Philippines

Philippine Navy rigid hull inflatable boats perform a maritime interdiction operation exercise in Manila Bay.

Philippine Navy rigid hull inflatable boats perform a maritime interdiction operation exercise in Manila Bay. Philippine Marine Corps push forward after splashing ashore in an amphibious assault vehicle during an exercise.

Philippine Marine Corps push forward after splashing ashore in an amphibious assault vehicle during an exercise. A NAVSOG unit climbs a caving ladder aboard the BRP Dagupan City during a maritime interdiction exercise.

A NAVSOG unit climbs a caving ladder aboard the BRP Dagupan City during a maritime interdiction exercise. Philippine Army Staff Sgt. Manolo Martin demonstrates the proper way to hold a king cobra during survival course training.

Philippine Army Staff Sgt. Manolo Martin demonstrates the proper way to hold a king cobra during survival course training. Airmen of the 710th Special Operations Wing prepare to jump from a KC-130 during Parachute Operations training.

Airmen of the 710th Special Operations Wing prepare to jump from a KC-130 during Parachute Operations training. A Philippine Army M113A2 FSV equipped with a UT30 25mm RCWS, being offloaded from BRP Tarlac (LD-601) in Iligan City during the Battle of Marawi.

A Philippine Army M113A2 FSV equipped with a UT30 25mm RCWS, being offloaded from BRP Tarlac (LD-601) in Iligan City during the Battle of Marawi.- The Northrop F-5 was the primary multi-role aircraft of the Philippine Air Force from 1967-2005.

BRP Gregorio del Pilar steam in formation together with BRP Edsa Dos during the sea phase of CARAT Philippines 2013.

BRP Gregorio del Pilar steam in formation together with BRP Edsa Dos during the sea phase of CARAT Philippines 2013. Philippine Air Force W-3A Sokol in combat helicopter paint scheme before transferring to search and rescue role.

Philippine Air Force W-3A Sokol in combat helicopter paint scheme before transferring to search and rescue role..jpg) Two FA-50 Jets of the Philippine Air Force.

Two FA-50 Jets of the Philippine Air Force. Two Del Pilar-class OPVs at Subic Bay Port

Two Del Pilar-class OPVs at Subic Bay Port The BRP Artemio Ricarte during the 2008 Balikatan exercise

The BRP Artemio Ricarte during the 2008 Balikatan exercise.jpg) The BRP Jose Rizal, the first purpose-built vessel of the Philippine Navy

The BRP Jose Rizal, the first purpose-built vessel of the Philippine Navy

- AFP Service Patches

Battledress identification patch of the Armed Forces of the Philippines

Philippine Army battledress patch

Philippine Air Force battledress patch  Philippine Marine Corps battledress pocket patch

Philippine Marine Corps battledress pocket patch

Philippine Navy battledress patch

(for NAVSOG Personnel in battledress uniform)

- AFP emblems and patches in the Commonwealth Era

Emblem of the Philippine Commonwealth Armed Forces, 1935-1946

Shoulder patch of the AFP General Staff, 1946-1965

See also

- AFP Modernization Act

- Awards and decorations of the Armed Forces of the Philippines

- List of AFP Chiefs of Staff

- Women in the Philippine military

- Philippine Constabulary

- Philippine Revolutionary Army

- Military History of the Philippines

- History of the Philippine Army

- List of conflicts in the Philippines

- List of wars involving the Philippines

References

- "Philippines Manpower available for military service".

- "Philippines Manpower fit for military service". IndexMundi.

- "2019 Philippines Military Strength". globalfirepower.com.

- Aika Rey (January 8, 2020). "Where will the money go?". Rappler. Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Central Intelligence Agency. "The World Factbook: Military Service Age and Obligation". Retrieved February 28, 2016.

17–23 years of age (officers 20–24) for voluntary military service; no conscription; applicants must be single male or female Philippine citizens with either 72 college credit hours (enlisted) or a baccalaureate degree (officers) (2013)

- "New AFP chief's 'top priority': Enforcing the Anti-Terror Law". Rappler. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- "AFP vice chief-of-staff Mison retires". www.pna.gov.ph.

- "AFP's second highest-ranking officer bows out from military service". Manila Bulletin News.

- Gotinga, J. C. "Philippine Fleet commander Giovanni Carlo Bacordo is new Navy chief". Rappler. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- Aguilar, Krissy. "Duterte names Allen Paredes as new Air Force chief". newsinfo.inquirer.net. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- "New PAF chief willing to be father, friend to Air Force members". www.pna.gov.ph. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- "DND, AFP welcome new Air Force chief". Manila Bulletin News. Retrieved January 17, 2020.

- "Casem takes over as Marines commandant". GMA News Online. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 1, 2019. Retrieved January 31, 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Speech of President Arroyo during the Commemoration of the Centennial Celebration of the end of the Philippine-American War April 16, 2002". Official Gazette. Government of the Philippines.

- "Commonwealth Act No. 1".

- See for example Manchester, William (1978). American Caesar: Douglas MacArthur 1880–1964. Boston: Little, Brown. ISBN 0-440-30424-5. OCLC 3844481.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- James, D. Clayton (1970). Volume 1, 1880–1941. The Years of MacArthur. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 505. ISBN 0-395-10948-5. OCLC 60070186.

- "Commonwealth Act No. 343 AN ACT TO ABOLISH THE STATE POLICE FORCE, TO REORGANIZE THE PHILIPPINE CONSTABULARY INTO A NATIONAL POLICE FORCE AND PROVIDING FUNDS THEREFOR". June 23, 1938.

- "Executive Ordef No. 153 s. 1938 Reorganizing the Philippine Constabulary into a National Police Force". June 23, 1938.

- "Santa Barbara Project – The Classified Missile Project of the Philippines". kbl.org.ph.

- "AFP hopes to recruit 20,000 soldiers in 3 years". ANC News. January 15, 2014. Archived from the original on March 2, 2014. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- "Republic Act No. 7898 : AFP Modernization Act" (PDF). Government of the Philippines. February 23, 1995.

- "REPUBLIC ACT NO. 10349 : AN ACT AMENDING REPUBLIC ACT NO. 7898, ESTABLISHING THE REVISED AFP MODERNIZATION PROGRAM AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES". Government of the Philippines. December 11, 2012.

- AFP Organization, [AFP website].

- https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1306237/ph-military-adopting-new-titles-chief-of-staff-now-joint-chiefs-chair/amp

- Republic Act No. 6975 (approved December 13, 1990), Chan Robles Law Library.

- Philippine National Police 19th Anniversary (January 28, 2010), Manila Bulletin (archived from the original Archived June 14, 2012, at the Wayback Machine on June 14, 2012).

- "AFP Organization". Archived from the original on April 19, 2008. Retrieved February 3, 2008.

- Comer 2010, pp. 6–7

- Comer 2010, p. 7

- Comer 2010, p. 8, Philippine Defense Reform (PDR), globalsecurity.org, DND and AFP: Transforming while Performing, Armed forces of the Philippines. (archived from the original Archived January 28, 2006, at the Wayback Machine on January 28, 2006)

- Comer 2010, pp. 12–14

- Comer 2010, p. 14, citing Philippine Defense Reform Handbook, Revised January 31, 2008.

- Comer 2010, p. 16

- Comer 2010, p. 21, Executive Order No. 240, Philippine Supreme Court E-Library. (archived from the original Archived August 15, 2011, at the Wayback Machine on April 29, 2012)

- Comer 2010, p. 18

- Comer 2010, p. 27

- Comer 2010, p. 34

- Comer 2010, p. 35

- Comer 2010, p. 36

- Promise 62: Implement the Defense Reform Program Archived March 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, ABS-CBN News.

- Aquino Promises Archived March 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, ABS-CBN News.

- "Defense.gov News Article: Hagel Praises 'Unbreakable' U.S.-Philippine Alliance".

- "PHL, US inch closer to deal on increased rotational presence of US troops". GMA News Online.

- Department of Environment and Natural Resources/United Nations Development Programme/Marine Environment and Resources Foundation, Inc. (2004) ArcDev: A Framework for Sustainable Archipelagic Development.

- Serafino, N. (2013). Security Assistance Reform: "Section 1206" Background and Issues for Congress. CRS Report for Congress. Accessed from: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/RS22855.pdf

- Voice of America (August 26, 2013). U.S. Significantly Boosts Military Funding for SE Asia. Voice of America. Accessed from: http://www.voanews.com/content/hagel-se-asia-corrected/1737438.html

- "The Triborder Sea Area: Maritime Southeast Asia's Ungoverned Space". Terrorism Monitor. The Jamestown Foundation. 5 (19). October 24, 2007.

- Jim Gomez (AP, Manila) (June 4, 2008). "Philippine Military Chief Says Armed Forces Not Strong Enough". The Irrawaddy. Archived from the original on January 20, 2011. Retrieved October 16, 2009.

- "EDITORIAL – Deadly weakness". The Philippine Star. September 17, 2011.

- "MUTUAL DEFENSE TREATY BETWEEN RP & USA – CHAN ROBLES VIRTUAL LAW LIBRARY".

- World Resources Institute (2012). Coastal and Marine Ecosystems – Marine Jurisdictions: Coastline Length. Accessed from: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 19, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) of_coastline

- Maritime Research Information Center (2013). Overview of the MRIC. Naval Station Francisco. Philippine Navy. Taguig City, Philippines. Accessed from: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 18, 2011. Retrieved June 12, 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- Executive Order No. 57 by the President of the Philippines. September 6, 2011. Accessed from: "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 25, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- https://pia.gov.ph/news/articles/1027673

- https://www.senate.gov.ph/press_release/2018/1004_gatchalian1.asp

- Comer, C. (2010). The Parting of the Sulawesi Sea: U.S. Strategy and Transforming the Terrorist Transit Triangle. United States Army Combined Arms Center. Accessed from: http://usacac.army.mil/cac2/call/docs/11-23/ch_13.asp

- "PA shooting team wins Asian Armies Skills at Arms Meet in Australia". balita.ph – Online Filipino News.

- "Philippine Army shooters among the best in the world – The Manila Times Online".

- "Pinoy peacekeepers in Golan Heights conferred prestigious UN medal". GMA News Online.

- Shoulder Ranks (Officers), The Philippine Army.(archived from the original Archived August 1, 2009, at the Wayback Machine on July 1, 2012)

- Philippine Military Rank Insignia, Globalsecurity.org.

- "Ferdinand E. Marcos". Archived from the original on August 4, 2008. Retrieved September 30, 2013., Malacañang Museum.

- "Fidel V. Ramos". Archived from the original on April 30, 2008. Retrieved April 30, 2008., Malacañang Museum.

- Rank insignia of the Philippine armed forces, scribd.com.

- 53rd PC Anniversary Yearbook, 1954 Edition

- Charles 'Ken' Comer, Philippine Defense Reform; Are we there yet?, Asia / South Pacific / India. Russian Military Security Watch, November 2010, U.S. Army Foreign Military Studies Office.

.svg.png)