Mexican Americans

Mexican Americans (Spanish: mexicano-estadounidenses or estadounidenses de origen mexicano) are Americans of full or partial Mexican descent. As of July 2018, Mexican Americans made up 11.3% of the United States' population, as 37.0 million U.S. residents identified as being of full or partial Mexican ancestry.[1] As of July 2018, Mexican Americans comprised 61.9% of all Latinos in Americans in the United States.[1] Many Mexican Americans reside in the American Southwest; over 60% of all Mexican Americans reside in the states of California and Texas.[9] As of 2016, Mexicans made up 53% of the total population of Latino foreign-born Americans. Mexicans are also the largest foreign-born population, accounting for 25% of the total foreign-born population, as of 2017.[10]

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 36,986,661 11.3% of total U.S. population, 2018[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

(also emerging populations in | |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholic[8] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Spanish Americans, Native Americans in the United States, other Hispanic and Latino Americans |

| Hispanic and Latino Americans |

|---|

|

National origin groups

|

|

Political movements

|

|

Organizations

|

|

Ethnic groups |

|

Lists

|

The United States is home to the second-largest Mexican community in the world, second only to Mexico itself, and comprising more than 24% of the entire Mexican-origin population of the world.[11] Mexican American families of indigenous heritage have been in the country for at least 15,000 years, and mestizo Mexican American history spans more than 400 years, since the 1598 founding of Spanish New Mexico. Spanish subjects of New Spain in the Southwest included New Mexican Hispanos and Pueblo Indians and Genizaros, Tejanos, Californios and Mission Indians have existed since the area was part of New Spain. The majority of these historically primarily Hispanophone populations eventually adopted English as their first language as part of their overall Americanization. Approximately ten percent of the current Mexican-American population are descended from the early colonial settlers who became U.S. citizens in 1848 via the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo which ended the Mexican–American War.[12]

Although most of the original Mexican American population were officially deemed white citizens by the treaty, they have faced and continue to face discrimination in the form of Anti-Mexican sentiment and Hispanophobia, historically rooted in the idea that Mexicans were "too Indian" to be citizens;[13] Indigenous Mexican Americans, such as Pueblo, were not granted citizenship until the 1920s. Despite assurances to the contrary, the property rights of formerly Mexican citizens were often not honored by the U.S. in accordance with modifications to and interpretations of the Treaty.[14][15][16] Continuous large-scale migration, particularly after the 1910 Mexican Revolution, added to this original population. During the Great Depression, Mexican Americans were scapegoated and subjected to an ethnic cleansing campaign of mass deportation, which affected an estimated 500,000 to two million people.[17][18][19][20] In violation of immigration law, the federal government allowed state and local governments to unilaterally deport citizens without due process. An estimated 85% of those ethnically cleansed were United States citizens, with 60% being birthright citizens.[20] The remaining population became more homogeneous and politically active during the New Deal — which largely excluded Mexican Americans — and the World War II era, which brought about the guest-worker Bracero Program.

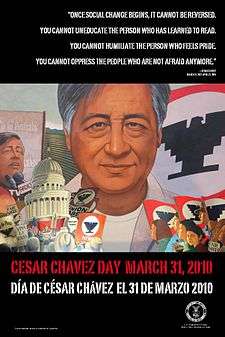

The 1965 Delano grape strike, sparked by mostly Filipino American farmworkers, became an intersectional struggle when labor leaders and voting rights and civil rights activists Dolores Huerta, founder of the National Farm Workers Association, and her co-leader César Chávez united with the strikers to form the United Farm Workers. Huerta's slogan "Sí, se puede" (Spanish for "Yes we can"), was popularized by Chávez's fast and became a rallying cry for the Chicano Movement, or Mexican American civil rights movement. The Chicano movement aimed for a variety of civil rights reforms, and was inspired by the civil rights movement; demands ranged from the restoration of land grants to farm workers' rights, to enhanced education, to voting and political rights, as well as emerging awareness of collective history. The Chicano walkouts of antiwar students is traditionally seen as the start of the more radical phase of the Chicano movement.[21][22]

Immigration from Mexico greatly increased in the 1980s and 1990s, peaking in the mid-2000s. In 2008, "Yes We Can" (in Spanish: "Sí, se puede") was adopted as the 2008 campaign slogan of Barack Obama, whose election and reelection as the first African American president underlined the growing importance of the Mexican American vote. The Great Recession led to a severe loss in Mexican-American wealth, and immigration from Mexico decreased.[23] The failure of both parties' presidents to properly enact immigration reform in the United States led to an increased polarization of how to handle an increasingly diverse population as Mexican Americans spread out from traditional centers in the Southwest and Chicago. In 2015, the United States admitted 157,227 Mexican immigrants,[24] and as of November 2016, 1.31 million Mexicans were on the waiting list to immigrate to the United States through legal means.[25]

History of Mexican Americans

In 1900, there were slightly more than 500,000 Hispanics of Mexican descent living in New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Colorado, California and Texas.[26] Most were Mexican Americans of Spanish descent and other Hispanicized European settlers who settled in the Southwest during Spanish colonial times, as well as local and Mexican Indians.

As early as 1813, some of the Tejanos who colonized Texas in the Spanish Colonial Period established a government in Texas that desired independence from Spanish-ruled Mexico. In those days, there was no concept of identity as Mexican. Many Mexicans were more loyal to their states/provinces than to their country as a whole, which was a colony of Spain. This was particularly true in frontier regions such as Zacatecas, Texas, Yucatán, Oaxaca, New Mexico, etc.[27]

As shown by the writings of colonial Tejanos such as Antonio Menchaca, the Texas Revolution was initially a colonial Tejano cause. Mexico encouraged immigration from the United States to settle east Texas and, by 1831, English-speaking settlers outnumbered Tejanos ten to one in the region. Both groups were settled mostly in the eastern part of the territory.[28] The Mexican government became concerned about the increasing volume of Anglo-American immigration and restricted the number of settlers from the United States allowed to enter Texas. Consistent with its abolition of slavery, the Mexican government banned slavery within the state, which angered American slave owners.[29] The American settlers, along with many of the Tejano, rebelled against the centralized authority of Mexico City and the Santa Anna regime, while other Tejano remained loyal to Mexico, and still others were neutral.[30][31]

Author John P. Schmal wrote of the effect Texas independence had on the Tejano community:

A native of San Antonio, Juan Seguín is probably the most famous Tejano to be involved in the War of Texas Independence. His story is complex because he joined the Anglo rebels and helped defeat the Mexican forces of Santa Anna. But later on, as Mayor of San Antonio, he and other Tejanos felt the hostile encroachments of the growing Anglo power against them. After receiving a series of death threats, Seguín relocated his family in Mexico, where he was coerced into military service and fought against the US in 1846–1848 Mexican–American War.[32]

Although the events of 1836 led to independence for the people of Texas, the Hispanic population of the state was very quickly disenfranchised, to the extent that their political representation in the Texas State Legislature disappeared entirely for several decades.

As a Spanish colony, the territory of California also had an established population of colonial settlers. Californios is the term for the Spanish-speaking residents of modern-day California; they were the original Mexicans (regardless of race) and local Hispanicized Indians in the region (Alta California) before the United States acquired it as a territory. In the mid-19th century, more settlers from the United States began to enter the territory.

In California, Spanish settlement began in 1769 with the establishment of the Presidio and Catholic mission of San Diego. 20 more missions were established along the California coast by 1823, along with military Presidios and civilian communities. Settlers in California tended to stay close to the coast and outside of the California interior. The California economy was based on agriculture and livestock. In contrast to central New Spain, coastal colonists found little mineral wealth. Some became farmers or ranchers, working for themselves on their own land or for other colonists. Government officials, priests, soldiers, and artisans settled in towns, missions, and presidios.[33]

One of the most important events in the history of Mexican settlers in California occurred in 1833, when the Mexican Government secularized the missions. In effect this meant that the government took control of large and vast areas of land. These lands were eventually distributed among the population in the form of Ranchos, which soon became the basic socio-economic units of the province.[33]

Relations between Californios and English-speaking settlers were relatively good until 1846, when military officer John C. Fremont arrived in Alta California with a United States force of 60 men on an exploratory expedition. Fremont made an agreement with Comandante Castro that he would stay in the San Joaquin Valley only for the winter, then move north to Oregon. However, Fremont remained in the Santa Clara Valley then headed towards Monterey. When Castro demanded that Fremont leave Alta California, Fremont rode to Gavilan Peak, raised a US flag and vowed to fight to the last man to defend it. After three days of tension, Fremont retreated to Oregon without a shot being fired.

With relations between Californios and Americans quickly souring, Fremont returned to Alta California, where he encouraged European-American settlers to seize a group of Castro's soldiers and their horses. Another group seized the Presidio of Sonoma and captured Mariano Vallejo.

The Americans chose William B. Ide as chosen Commander in Chief and on July 5, he proclaimed the creation of the Bear Flag Republic. On July 9, US military forces reached Sonoma; they lowered the Bear Flag Republic's flag, replacing it with a US flag. Californios organized an army to defend themselves from invading American forces after the Mexican army retreated from Alta California to defend other parts of Mexico.

The Californios defeated an American force in Los Angeles on September 30, 1846. In turn, they were defeated after the Americans reinforced their forces in what is now southern California. Tens of thousands of miners and associated people arrived during the California Gold Rush, and their activities in some areas meant the end of the Californios' ranching lifestyle. Many of the English-speaking 49ers turned from mining to farming and moved, often illegally, onto land granted to Californios by the former Mexican government.[34]

The United States had first come into conflict with Mexico in the 1830s, as the westward spread of United States settlements and of slavery brought significant numbers of new settlers into the region known as Tejas (modern-day Texas), then part of Mexico. The Mexican–American War, followed by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 and the Gadsden Purchase in 1853, extended US control over a wide range of territory once held by Mexico, including the present-day borders of Texas and the states of New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, and California.

Although the treaty promised that the landowners in this newly acquired territory would have their property rights preserved and protected as if they were citizens of the United States, many former citizens of Mexico lost their land in lawsuits before state and federal courts over terms of land grants, or as a result of legislation passed after the treaty.[35] Even those statutes which Congress passed to protect the owners of property at the time of the extension of the United States' borders, such as the 1851 California Land Act, had the effect of dispossessing Californio owners. They were ruined by the cost over years of having to maintain litigation to support their land titles.

Following the concession of California to the United States under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Mexicans were repeatedly targeted by legislation that targeted their socio-economic standing in the area. One significant instance of this is exemplified by the passage of legislation that placed the heaviest tax burden on land. The fact that there was such a heavy tax on land was important to the socio-economic standing of Mexican Americans, because it essentially limited their ability to keep possession of the Ranchos that had been originally granted to them by the Mexican government.[33]

19th-century and Early 20th-century Mexican migration

In the late nineteenth century, liberal Mexican President Porfirio Díaz embarked on a program of economic modernization that triggered not only a wave of internal migration in Mexico from rural areas to cities, but also Mexican emigration to the United States. A railway network was constructed that connected central Mexico to the U.S. border and also opened up previously isolated regions. The second factor was the shift in land tenure that left Mexican peasants without title or access to land for farming on their own account.[36] For the first time, Mexicans in increasing numbers migrated north into the U.S. for better economic opportunities. In the early 20th century, the first main period of migration to the United States happened between the 1910s to the 1920s, referred to as the Great Migration.[37] During this time period the Mexican Revolution was taking place, creating turmoil within and against the Mexican government causing civilians to seek out economic and political stability in the United States. Over 1.3 million Mexicans relocated to the United States from 1910 well into the 1930s, with significant increases each decade.[38] Many of these immigrants found agricultural work, being contracted under private laborers.[39] The second period of increased migration is known as the Bracero Era from 1942 to 1964, referring to the Bracero program implemented by the United States, contracting agricultural labor from Mexico due to labor shortages from the World War II draft. An estimated 4.6 million Mexican immigrants were pulled into U.S. through the Bracero Program from the 1940s to the 1960s.[40] The lack of agricultural laborers due to increases in military drafts for World War II opened up a chronic need for low wage workers to fill jobs.

Late 20th century

.jpg)

While Mexican Americans are concentrated in the Southwest: California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. During World War I many moved to industrial communities such as St. Louis, Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and other steel-producing regions, where they gained industrial jobs. Like European immigrants, they were attracted to work that did not require proficiency in English. Industrial restructuring in the second half of the century put many Mexican Americans out of work in addition to people of other ethnic groups. Their industrial skills were not as useful in the changing economies of these areas

During the first half of the 20th century, Mexican-American workers formed unions of their own and joined integrated unions. The most significant union struggle involving Mexican Americans was the effort to organize agricultural workers and the United Farm Workers' long strike and boycott aimed at grape growers in the San Joaquin and Coachella valleys in the late 1960s. Leaders César Chávez and Dolores Huerta gained national prominence as they led a workers' rights organization that helped workers get unemployment insurance to an effective union of farmworkers almost overnight. The struggle to protect rights and sustainable wages for migrant workers has continued.

Since the late 20th century, undocumented Mexican immigrants have increasingly become a large part of the workforce in industries such as meat packing, where processing centers have moved closer to ranches in relatively isolated rural areas of the Midwest; in agriculture in the southeastern United States; and in the construction, landscaping, restaurant, hotel and other service industries throughout the country.

Mexican-American identity has changed throughout these years. Over the past hundred years, activist Mexican Americans have campaigned for their constitutional rights as citizens, to overturn discrimination in voting and to gain other civil rights. They have opposed educational and employment discrimination, and worked for economic and social advancement. In numerous locations, court cases have been filed under the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to challenge practices, such as poll taxes and literacy tests in English, that made it more difficult for Spanish-language minorities to register and vote. At the same time, many Mexican Americans have struggled with defining and maintaining their community's cultural identity as distinct from mainstream United States. That changes in response to the absorption of countless new immigrants.

In the 1960s and 1970s, some Latino/Hispanic student groups flirted with Mexican nationalism, and differences over the proper name for members of the community. Discussion over self-identification as Chicano/Chicana, Latino/Latina, Mexican Americans, or Hispanics became tied up with deeper disagreements over whether to integrate into or remain separate from mainstream American society. There were divisions between those Mexican Americans whose families had lived in the United States for two or more generations and more recent immigrants, in addition to distinctions from other Hispanic or Latino immigrants from nations in Central and South America with their own distinct cultural traditions.

During this period, civil rights groups such as the National Mexican-American Anti-Defamation Committee were founded. By the early 21st century, the states with the largest percentages and populations of Mexican Americans are California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Colorado, Nevada, and Utah. There have also been markedly increasing populations in Oklahoma, Pennsylvania and Illinois.[41]

In terms of religion, Mexican Americans are primarily Roman Catholic.[42] A large minority are Evangelical Protestants. Notably, according to a Pew Hispanic Center report in 2006 and the Pew Religious Landscape Survey in 2008, Mexican Americans are significantly less likely than other Hispanic groups to abandon Catholicism for Protestant churches.[43][44]

Race and ethnicity

Ethnically, Mexican Americans are a diverse population, including those of European ancestry, Indigenous ancestry, a mixture of both, and Mexicans of Middle Eastern descent (mainly Lebanese). The Mexican population is majority Mestizo, which in colonial times meant to be a person of half European and half Native American ancestry. Nonetheless the meaning of the word has changed through time, currently being used to refer to the segment of the Mexican population who does not speak indigenous languages,[46] thus in Mexico, the term "Mestizo" has become a cultural label rather than a racial one, it is vaguely defined and includes people who does not have Indigenous ancestry, people who does not have European ancestry as well as people of African ancestry.[47] Such transformation of the word is not a casualty but the result of a concept known as "mestizaje", which was promoted by the post-revolutionary Mexican government in an effort to create a united Mexican ethno-cultural identity with no racial distinctions.[48] It is because of this that sometimes the Mestizo population in Mexico is estimated to be as high as 93% of the Mexican population.[49]

Per the 2010 US Census, the majority (52.8%) of Mexican Americans identified as being White.[50] The remainder identified themselves as being of "some other race" (39.5%), "two or more races" (5.0%), Native American (1.4%), black (0.9%), and Asian / Pacific Islander (0.4%).[50] It is notable that only 5% of Mexican Americans reported being of two or more races despite the presumption of mestizaje among the Mexican population in Mexico.

This identification as "some other race" reflects activism among Mexican Americans as claiming a cultural status and working for their rights in the United States, as well as the separation due to different language and culture. Hispanics are not a racial classification, however, but an ethnic group.

Genetic studies made in the Mexican population have found European ancestry ranging from 56%[51] going to 60%,[52] 64%[53] and up to 78%.[54] In general, Mexicans have both European and Amerindian ancestries, and the proportion varies by region and individuals. African ancestry is also present, but in lower proportion. There is genetic asymmetry, with the direct paternal line predominately European and the maternal line predominately Amerindian.

For instance, a 2006 study conducted by Mexico's National Institute of Genomic Medicine (INMEGEN), which genotyped 104 samples, reported that Mestizo Mexicans are 58.96% European, 35.05% "Asian" (primarily Amerindian), and 5.03% Other.[55] According to a 2009 report by the Mexican Genome Project, which sampled 300 Mestizos from six Mexican states and one indigenous group, the gene pool of the Mexican Mestizo population was calculated to be 55.2% percent indigenous, 41.8% European, 1.0% African, and 1.2% Asian.[56] A 2012 study published by the Journal of Human Genetics found the deep paternal ancestry of the Mexican Mestizo population to be predominately European (64.9%) followed by Amerindian (30.8%) and Asian (1.2%).[57] An autosomal ancestry study performed on Mexico City reported that the European ancestry of Mexicans was 52% with the rest being Amerindian and a small African contribution, additionally maternal ancestry was analyzed, with 47% being of European origin. Unlike previous studies which only included Mexicans who self-identified as Mestizos, the only criteria for sample selection in this study was that the volunteers self-identified as Mexicans.[58]

While Mexico does not have comprehensive modern racial censuses, some international publications believe that Mexican people of predominately European descent (Spanish or other European) make up approximately one-sixth (16.5%), this based on the figures of the last racial census in the country, made in 1921.[59] According to an opinion poll conducted by the Latinobarómetro organization in 2011, 52% of Mexican respondents said they were Mestizos, 19% Indigenous, 6% White, 2% Mulattos and 3% "other race."[60]

US census bureau classifications

As the United States' borders expanded, the United States Census Bureau changed its racial classification methods for Mexican Americans under United States jurisdiction. The Bureau's classification system has evolved significantly from its inception:

- From 1790 to 1850, there was no distinct racial classification of Mexican Americans in the US census. The categories recognized by the Census Bureau were White, Free People of Color, and Black. The Census Bureau estimates that during this period the number of persons who could not be categorized as white or black did not exceed 0.25% of the total population based on 1860 census data.[61]

- From 1850 through 1920, the Census Bureau expanded its racial categories to include multi-racial persons, under Mestizos, Mulattos, as well as new categories of distinction of Amerindians and Asians. It classified Mexicans and Mexican Americans as "White".[61]

- The 1930 US census revoked generic white status for Mexican Americans due to protests among certain parts of the population over a diluted definition of "whiteness." This decision followed a period in which Virginia and some other racially segregated states passed laws imposing binary classification and the one-drop rule, requiring classification of all persons with any known African ancestry as "black." The new form asked for "color or race." Census workers were instructed to differentiate between European whites and known people of Mexican descent, and to "write ‘W’ for White; and ’Mex’ for Mexican."[62]

- In the 1940 census, due to widespread protests by the Mexican American community following the 1930 changes, Mexican Americans were re-classified as White, . Instructions for enumerators were: "Mexicans – Report 'White' (W) for Mexicans unless they are definitely of indigenous or other non-white race." During the same census, however, the bureau began to track the White population of Spanish mother tongue. This practice continued through the 1960 census.[61] The 1960 census also used the title "Spanish-surnamed American" in their reporting data of Mexican Americans; this category also covered Cuban Americans, Puerto Ricans and others under the same category.

- From 1970 to 1980, there was a dramatic increase in the number of people who identified as "of Other Race" in the census, reflecting the addition of a question on 'Hispanic origin' to the 100-percent questionnaire, an increased propensity for Hispanics to identify as other than White as they agitated for civil rights, and a change in editing procedures to accept reports of "Other race" for respondents who wrote in ethnic Hispanic entries, such as Mexican, Cuban, or Puerto Rican. In 1970, such responses in the Other race category were reclassified and tabulated as White. During this census, the bureau attempted to identify all Hispanics by use of the following criteria in sampled sets:[61]

- Spanish speakers and persons belonging to a household where the head of household was a Spanish speaker

- persons with Spanish heritage by birth location or surname

- Persons who self-identified Spanish origin or descent

- From 1980 on, the Census Bureau has collected data on Hispanic origin on a 100-percent basis. The bureau has noted an increasing number of respondents who identify as of Hispanic origin but not of the White race.[61]

For certain purposes, respondents who wrote in "Chicano" or "Mexican" (or indeed, almost all Hispanic origin groups) in the "Some other race" category were automatically re-classified into the "White race" group.[63]

Politics and debate of racial classification

In some cases, legal classification of White racial status has made it difficult for Mexican-American rights activists to prove minority discrimination. In the case Hernandez v. Texas (1954), civil rights lawyers for the appellant, named Pedro Hernandez, were confronted with a paradox: because Mexican Americans were classified as White by the federal government and not as a separate race in the census, lower courts held that they were not being denied equal protection by being tried by juries that excluded Mexican Americans by practice. The lower court ruled there was no violation of the Fourteenth Amendment by excluding people with Mexican ancestry among the juries. Attorneys for the state of Texas and judges in the state courts contended that the amendment referred only to racial, not "nationality," groups. Thus, since Mexican Americans were tried by juries composed of their racial group—whites—their constitutional rights were not violated. The US Supreme Court ruling in Hernandez v. Texas case held that "nationality" groups could be protected under the Fourteenth Amendment, and it became a landmark in the civil rights history of the United States.[64][65]

While Mexican Americans were allowed to serve in all-White units during World War II, many Mexican–American veterans were discriminated against and even denied medical services by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs when they arrived home. They created the G.I. Forum to work for equal treatment.[66]

In times and places in the United States where Mexicans were classified as White, they were permitted by law to intermarry with what today are termed "non-Hispanic Whites." Social customs typically approved of such marriages only if the Mexican partner was not of visible indigenous ancestry.[67]

Legally, Mexican Americans could vote and hold elected office; however, in many states electoral practices discriminated against them, especially as a language minority. After they created political organizations such as the League of United Latin America Citizens and the G.I. Forum, Mexican Americans began to exert more political influence and gain elective office. Edward Roybal's election to the Los Angeles City Council in 1949 and to Congress in 1962 also represented this rising Mexican-American political power.

In the late 1960s the founding of the Crusade for Justice in Denver and the land grant movement in New Mexico in 1967 set the bases for what would become known as Chicano (Mexican American) nationalism. The 1968 Los Angeles, California school walkouts expressed Mexican-American demands to end de facto ethnic segregation (also based on residential patterns), increase graduation rates, and reinstate a teacher fired for supporting student political organizing. A notable event in the Chicano movement was the 1972 Convention of La Raza Unida (United People) Party, which organized with the goal of creating a third party to give Chicanos political power in the U.S.[66]

In the past, Mexicans were legally considered "White" because either they were accepted as being of Spanish ancestry, or because of early treaty obligations to Spaniards and Mexicans that conferred citizenship status to Mexican peoples before the American Civil War. Numerous slave states bordered Mexican territory at a time when 'whiteness' was nearly a prerequisite for US citizenship in those states.[68][69]

Although Mexican Americans were legally classified as "White" in terms of official federal policy, socially they were seen as "too Indian" to be treated as such.[13] Many organizations, businesses, and homeowners associations and local legal systems had official policies in the early 20th century to exclude Mexican Americans in a racially discriminatory way.[70] Throughout the Southwest, discrimination in wages was institutionalized in "White wages" versus lower "Mexican wages" for the same job classifications.[70] For Mexican Americans, opportunities for employment were largely limited to guest worker programs.[70]

The bracero program, begun in 1942 during World War II, when many United States men were drafted for war, allowed Mexicans temporary entry into the U.S. as migrant workers at farms throughout California and the Southwest. This program continued until 1964.[55][71][72]

A number of western states passed anti-miscegenation laws, directed chiefly at Chinese and Japanese. As Mexican Americans were then classified as "White" by the census, they could not legally marry African or Asian Americans (See Perez v. Sharp).[73] According to historian Neil Foley in his book The White Scourge: Mexicans, Blacks, and Poor Whites in Texas Cotton Culture, Mexicans and Mexican-Americans in Texas did marry non-Whites, typically without reprisal.[74]

While of racial segregation and discrimination against both Mexican American and African American minorities were subject to segregation and racial discrimination, they were treated differently. There were legal racial demarcations between Whites and blacks in a state like Texas, whereas the line between Whites and Mexican Americans was not legally defined. Mexican Americans could attend White schools and colleges (which were racially segregated against blacks), mix socially with Whites and, marry Whites. These choices were prohibited to African Americans under state laws. Racial segregation operated separately from economic class and was rarely as rigid for Mexican Americans as it was for African Americans. For instance, even when some African Americans in Texas enjoyed higher economic status than Mexican Americans (or Whites) in an area, they were still segregated by law.[75]

Demographics

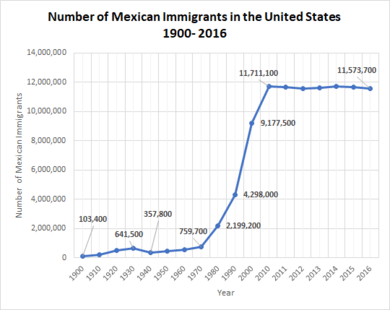

Mexican-Born population over time

| Year | Population[10] | Percentage of all U.S. immigrants |

|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 13,300 | 0.6 |

| 1860 | 27,500 | 0.7 |

| 1870 | 42,400 | 0.8 |

| 1880 | 68,400 | 1.0 |

| 1890 | 77,900 | 0.8 |

| 1900 | 103,400 | 1.0 |

| 1910 | 221,900 | 1.6 |

| 1920 | 486,400 | 3.5 |

| 1930 | 641,500 | 4.5 |

| 1940 | 357,800 | 3.1 |

| 1950 | 451,400 | 3.9 |

| 1960 | 575,900 | 5.9 |

| 1970 | 759,700 | 7.9 |

| 1980 | 2,199,200 | 15.6 |

| 1990 | 4,298,000 | 21.7 |

| 2000 | 9,177,500 | 29.5 |

| 2010 | 11,711,700 | 29.3 |

| 2017 | 11,269,900 | 25.3 |

Culture

Economic and social issues

Immigration issues

- See also Strangers No Longer: Together on the Journey of Hope, a pastoral letter written by both the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops and the Mexican Episcopal Conference, which deals with the issue of migration in the context of the United States and Mexico.

Since the 1960s, Mexican immigrants have met a significant portion of the demand for cheap labor in the United States.[78] Fear of deportation makes them highly vulnerable to exploitation by employers. Many employers, however, have developed a "don't ask, don't tell" attitude toward hiring undocumented Mexican nationals. In May 2006, hundreds of thousands of undocumented immigrants, Mexicans and other nationalities, walked out of their jobs across the country in protest to support immigration reform (many in hopes of a path to citizenship similar to the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 signed into law by President Ronald Reagan, which granted citizenship to Mexican nationals living and working without documentation in the US).

Even legal immigrants to the United States, both from Mexico and elsewhere, have spoken out against illegal immigration. However, according to a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center in June 2007, 63% of Americans would support an immigration policy that would put undocumented immigrants on a path to citizenship if they "pass background checks, pay fines and have jobs, learn English", while 30% would oppose such a plan. The survey also found that if this program was instead labeled "amnesty", 54% would support it, while 39% would oppose.[79]

Alan Greenspan, former Chairman of the Federal Reserve, has said that the growth of the working-age population is a large factor in keeping the economy growing and that immigration can be used to grow that population. According to Greenspan, by 2030, the growth of the US workforce will slow from 1 percent to 1/2 percent, while the percentage of the population over 65 years will rise from 13 percent to perhaps 20 percent.[80] Greenspan has also stated that the current immigration problem could be solved with a "stroke of the pen", referring to the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2007 which would have strengthened border security, created a guest worker program, and put undocumented immigrants currently residing in the US on a path to citizenship if they met certain conditions.[81]

According to data published by the Bank of Mexico, Mexicans in the United States sent $24.7 billion in remittances to Mexico in 2015.[82]

Discrimination and stereotypes

Throughout US history, Mexican Americans have endured various types of negative stereotypes which have long circulated in media and popular culture.[83][84] Mexican Americans have also faced discrimination based on ethnicity, race, culture, poverty, and use of the Spanish language.[85]

Since the majority of undocumented immigrants in the US have traditionally been from Latin America, the Mexican American community has been the subject of widespread immigration raids. During The Great Depression, the United States government sponsored a Mexican Repatriation program which was intended to encourage people to voluntarily move to Mexico, but thousands were deported against their will. More than 500,000 individuals were deported, approximately 60 percent of which were actually United States citizens.[86][87] In the post-war era, the Justice Department launched Operation Wetback.[87]

During World War II, more than 300,000 Mexican Americans served in the US armed forces.[35] Mexican Americans were generally integrated into regular military units; however, many Mexican–American War veterans were discriminated against and even denied medical services by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs when they arrived home.[55] In 1948, war veteran Hector P. Garcia founded the American GI Forum to address the concerns of Mexican American veterans who were being discriminated against. The AGIF's first campaign was on the behalf of Felix Longoria, a Mexican American private who was killed in the Philippines while in the line of duty. Upon the return of his body to his hometown of Three Rivers, Texas, he was denied funeral services because of his nationality.

In the 1948 case of Perez v. Sharp, the Supreme Court of California recognized that interracial bans on marriage violated the Fourteenth Amendment of the Federal Constitution. The case involved Andrea Perez, a Mexican-American woman listed as White, and Sylvester Davis, an African American man.[88]

In 2006, Time magazine reported that the number of hate groups in the United States increased by 33% since 2000, with illegal immigration being used as a foundation for recruitment.[89] According to the 2011 Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Hate Crimes Statistics Report, 56.9% of the 939 victims of crimes motivated by a bias toward the victims’ ethnicity or national origin were directed at Hispanics.[90] In California, the state with the largest Mexican American population, the number of hate crimes committed against Latinos almost doubled from 2003 to 2007.[91][92] In 2011, hate crimes against Hispanics declined 31% in the United States and 43% in California.[93]

In 2016, Donald Trump won the presidency with an estimated 28 percent Mexican American vote .

Social status and assimilation

There have been increases in average personal and household incomes for Mexican Americans in the 21st century. US-born Americans of Mexican heritage earn more and are represented more in the middle and upper-class segments more than most recently arriving Mexican immigrants.

Most immigrants from Mexico, as elsewhere, come from the lower classes and from families generationally employed in lower skilled jobs. They also are most likely from rural areas. Thus, many new Mexican immigrants are not skilled in white collar professions. Recently, some professionals from Mexico have been migrating, but to make the transition from one country to another involves re-training and re-adjusting to conform to US laws —i.e. professional licensing is required.[94]

According to James P. Smith, the children and grandchildren of Latino immigrants tend to lessen educational and income gaps with White American. Immigrant Latino men earn about half of what whites make, while second generation US-born Latinos make about 78 percent of the salaries of their white counterparts and by the third generation US-born Latinos make on average identical wages to their US-born white counterparts.[95] However, the number of Mexican American professionals have been growing in size since 2010.[96]

.png)

The Mexican median household income was a mere $37,390 compared to that of $49,487 and $54,656 for immigrants and native-born populations respectively. This pushed 28% of Mexican families to live in poverty, to put that in perspective the rest of the immigrants where at 18% and native-born families 10%.

Huntington (2005) argues that the sheer number, concentration, linguistic homogeneity, and other characteristics of Latin American immigrants will erode the dominance of English as a nationally unifying language, weaken the country's dominant cultural values, and promote ethnic allegiances over a primary identification as an American. Testing these hypotheses with data from the US Census and national and Los Angeles opinion surveys, Citrin et al. (2007) show that Hispanics generally acquire English and lose Spanish rapidly beginning with the second generation, and appear to be no more or less religious or committed to the work ethic than native-born non-Mexican American whites. However, the children and grandchildren of Mexican immigrants were able to make close ties with their extended families in Mexico, since United States shares a 2,000 mile border with Mexico. Many had the opportunity to visit Mexico on a relatively frequent basis. As a result, many Mexicans were able to maintain a strong Mexican culture, language, and relationship with others.[97]

South et al. (2005) examine Hispanic spatial assimilation and inter-neighborhood geographic mobility. Their longitudinal analysis of seven hundred Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Cuban immigrants followed from 1990 to 1995 finds broad support for hypotheses derived from the classical account of assimilation into American society. High income, English-language use, and embeddedness in American social contexts increased Latin American immigrants' geographic mobility into multi-ethnic neighborhoods. US citizenship and years spent in the United States were positively associated with geographic mobility into different neighborhoods while co-ethnic contact and prior experiences of ethnic discrimination decreased the likelihood that Latino immigrants would move from their original neighborhoods and into non-Hispanic White census tracts.[98]

Intermarriage

According to 2000 census data, US-born ethnic Mexicans have a high degree of intermarriage with non-Hispanic Whites. Based on a sample size of 38,911 U.S.-born Mexican husbands and 43,527 U.S.-born Mexican wives:[100]

- 50.6% of US-born Mexican men and 45.3% of US-born Mexican women married US-born Mexicans;[100]

- 26.7% of US-born Mexican men and 28.1% of US-born Mexican women married non-Hispanic Whites; and[100]

- 13.6% of US-born Mexican men and 17.4% of US-born Mexican women married Mexico-born Mexicans.[100]

In addition, based on 2000 data, there is a significant amount of ethnic absorption of ethnic Mexicans into the mainstream population with 16% of the children of mixed marriages not being identified in the census as Mexican.[101]

A study done by the National Research Council (US) Panel on Hispanics in the United States published in 2006 looked at not only marriages, but also non-marriage unions. It found that since at least 1980, marriage for females across all Hispanic ethnic groups, including Mexican Americans, has been in a steady decline.[102] In addition, the percentage of births to unmarried mothers increased for females of Mexican descent from 20.3% in 1980 to 40.8% in 2000, more than doubling in that time frame.[102] The study also found that for females of all Hispanic ethnicities, including Mexican origin, "considerably fewer births to unmarried Hispanic mothers involve partnerships with non-Hispanic white males than is the case for married Hispanic mothers. Second, births outside marriage are more likely to involve a non-Hispanic black father than births within marriage."[102] Additionally, "Unions among partners from different Hispanic origins or between Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks are considerably more evident in cohabitation and parenthood than they are in marriage. In particular, unions between Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks are prominent in parenthood, especially non-marital births."[102] Furthermore, for 29.7% of unmarried births to native-born females of Mexican origin and 40% of unmarried births to females of "Other Hispanic" origin, which may include Mexican American, information on the father's ethnicity was missing.[102] The study was supported by the U.S. Census Bureau, amongst other sources.[102]

Segregation issues

Housing market practices

Studies have shown that the segregation among Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants seems to be declining. One study from 1984 found that Mexican American applicants were offered the same housing terms and conditions as non-Hispanic White Americans. They were asked to provide the same information (regarding employment, income, credit checks, etc.) and asked to meet the same general qualifications of their non-Hispanic White peers.[103] In this same study, it was found that Mexican Americans were more likely than non-Hispanic White Americans to be asked to pay a security deposit or application fee[103] and Mexican American applicants were also more likely to be placed onto a waiting list than non-Hispanic White applicants.[103]

Battle of Chavez Ravine

The Battle of Chavez Ravine has several meanings, but often refers to controversy surrounding government acquisition of land largely owned by Mexican Americans in Los Angeles' Chavez Ravine over approximately ten years (1951–1961). The eventual result was the removal of the entire population of Chavez Ravine from land on which Dodger Stadium was later constructed.[104] The great majority of the Chavez Ravine land was acquired to make way for proposed public housing. The public housing plan that had been advanced as politically "progressive" and had resulted in the removal of the Mexican American landowners of Chavez Ravine, was abandoned after passage of a public referendum prohibiting the original housing proposal and election of a conservative Los Angeles mayor opposed to public housing. Years later, the land acquired by the government in Chavez Ravine was dedicated by the city of Los Angeles as the site of what is now Dodger Stadium.[104]

Latino segregation versus Black segregation

When comparing the contemporary segregation of Mexican Americans to that of Black Americans, some scholars claim that "Latino segregation is less severe and fundamentally different from Black residential segregation." suggesting that the segregation faced by Latinos is more likely to be due to factors such as lower socioeconomic status and immigration while the segregation of African Americans is more likely to be due to larger issues of the history of racism in the US.[105]

Legally, Mexican Americans could vote and hold elected office, however, it was not until the creation of organizations such as the League of United Latin America Citizens and the G.I. Forum that Mexican Americans began to achieve political influence. Edward Roybal's election to the Los Angeles City Council in 1949 and then to Congress in 1962 also represented this rising Mexican American political power.[106] In the late 1960s the founding of the Crusade for Justice in Denver in and the land grant movement in New Mexico in 1967 set the bases for what would become the Chicano (Mexican American) nationalism. The 1968 Los Angeles school walkouts expressed Mexican American demands to end segregation, increase graduation rates, and reinstate a teacher fired for supporting student organizing. A notable event in the Chicano movement was the 1972 Convention of La Raza Unida (United People) Party, which organized with the goal of creating a third party that would give Chicanos political power in the U.S.[66]

In the past, Mexicans were legally considered "White" because either they were considered to be of full Spanish heritage, or because of early treaty obligations to Spaniards and Mexicans that conferred citizenship status to Mexican peoples at a time when whiteness was a prerequisite for US citizenship.[68][69] Although Mexican Americans were legally classified as "White" in terms of official federal policy, many organizations, businesses, and homeowners associations and local legal systems had official policies to exclude Mexican Americans. Throughout the southwest discrimination in wages were institutionalized in "white wages" versus lower "Mexican wages" for the same job classifications. For Mexican Americans, opportunities for employment were largely limited to guest worker programs. The bracero program, which began in 1942 and officially ended in 1964, allowed them temporary entry into the U.S. as migrant workers in farms throughout California and the Southwest.[55][70][71][72]

Mexican Americans legally classified as "White", following anti-miscegenation laws in most western states until the 1960s, could not legally marry African or Asian Americans (See Perez v. Sharp).[88] However, most were not socially considered white, and therefore, according to Historian Neil Foley in the book The White Scourge: Mexicans, Blacks, and Poor Whites in Texas Cotton Culture, Mexicans and Mexican-Americans did marry non-whites typically without reprisal.

Despite the similarities between Mexican American and African American patterns of segregation, there were important differences. The racial demarcations between whites and blacks in a state like Texas were inviolable, whereas those between whites and Mexican Americans were not. It was possible for Mexican Americans to attend white schools and colleges, mix socially with whites and, on occasion, marry whites: all of these things were impossible for African Americans, largely due to the legalized nature of black-white segregation. Racial segregation was rarely as rigid for Mexican Americans as it was for African Americans, even in situations where African Americans enjoyed higher economic status than Mexican Americans.[75]

Segregated schools

During certain periods , Mexican American children sometimes were forced to register at "Mexican schools", where classroom conditions were poor, the school year was shorter, and the quality of education was substandard.[107]

Various reasons for the inferiority of the education given to Mexican American students have been listed by James A. Ferg-Cadima including: inadequate resources, poor equipment, unfit building construction. In 1923, the Texas Education Survey Commission found that the school year for some non-white groups was 1.6 months shorter than the average school year.[107] Some have interpreted the shortened school year as a "means of social control" implementing policies to ensure that Mexican Americans would maintain the unskilled labor force required for a strong economy. A lesser education would serve to confine Mexican Americans to the bottom rung of the social ladder. By limiting the number of days that Mexican Americans could attend school and allotting time for these same students to work, in mainly agricultural and seasonal jobs, the prospects for higher education and upward mobility were slim.[107]

Immigration and segregation

Immigration hubs are popular destinations for Latino immigrants. These segregated areas have historically served the purpose of allowing immigrants to become comfortable in the United States, accumulate wealth, and eventually leave.[108]

This model of immigration and residential segregation, explained above, is the model which has historically been accurate in describing the experiences of Latino immigrants. However, the patterns of immigration seen today no longer follows this model. This old model is termed the standard spatial assimilation model. More contemporary models are the polarization model and the diffusion model: The spatial assimilation model posits that as immigrants would live within this country's borders, they would simultaneously become more comfortable in their new surroundings, their socioeconomic status would rise, and their ability to speak English would increase. The combination of these changes would allow for the immigrant to move out of the barrio and into the dominant society. This type of assimilation reflects the experiences of immigrants of the early twentieth century.[105]

Polarization model suggests that the immigration of non-Black minorities into the United States further separates Blacks and Whites, as though the new immigrants are a buffer between them. This creates a hierarchy in which Blacks are at the bottom, Whites are at the top, and other groups fill the middle. In other words, the polarization model posits that Asians and Hispanics are less segregated than their African American peers because White American society would rather live closer to Asians or Hispanics than African Americans.[108]

The diffusion model has also been suggested as a way of describing the immigrant's experience within the United States. This model is rooted in the belief that as time passes, more and more immigrants enter the country. This model suggests that as the United States becomes more populated with a more diverse set of peoples, stereotypes and discriminatory practices will decrease, as awareness and acceptance increase. The diffusion model predicts that new immigrants will break down old patterns of discrimination and prejudice, as one becomes more and more comfortable with the more diverse neighborhoods that are created through the influx of immigrants.[108] Applying this model to the experiences of Mexican Americans forces one to see Mexican American immigrants as positive additions to the "American melting pot," in which as more additions are made to the pot, the more equal and accepting society will become.

The Chicano movement and the Chicano Moratorium

In the heady days of the late 1960s, when the student movement was active around the globe, the Chicano movement conducted actions such as the mass walkouts by high school students in Denver and [[East Los Angeles, California] in 1968 and the Chicano Moratorium in Los Angeles in 1970. The movement was particularly strong at the college level, where activists formed MEChA, an organization that seeks to promote Chicano unity and empowerment through education and political action, but also espouses revanchist ideals centered around "taking back" the American southwest for Mexican- Americans (Chicanos) through education. The new Chicano college graduate's ideal was to become empowered through education, return to his/her community and advise more chicanos to continue with their college education after high school. And upon graduation, the purpose was to return to their communities and advise other members of their families and ethnic groups to follow their footsteps. The communities political positions, and management positions were going to be reached by empowering chicanos through higher education and become involved in city councils, management positions, and politics (Pinzon, 2015)

The Chicano Moratorium, formally known as the National Chicano Moratorium Committee, was a movement of Chicano anti-war activists that built a broad-based but fragile coalition of Mexican-American groups to organize opposition to the Vietnam War. The committee was led by activists from local colleges and members of the "Brown Berets", a group with roots in the high school student movement that staged walkouts in 1968, known as the East L.A. walkouts, also called "blowouts".

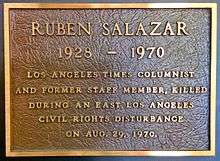

The best known historical fact of the Moratorium was the death of Rubén Salazar, known for his reporting on civil rights and police brutality. The official story is that Salazar was killed by a tear gas canister fired by a member of the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department into the Silver Dollar Café at the conclusion of the August 29 rally.

Education

Parental Involvement

Parents are commonly associated with being a child's first teacher. As the child grows older, the parent's role in their child's learning may change; however, a parent will often continue to serve as a role model. There are multiple research articles that have looked at parental involvement and education. A key aspect of parental involvement in education is that it can be transmitted in many ways. For a long time, there has been a misconception that the parents of Mexican American students are not involved in their children's education; however, multiple studies have demonstrated that parents are involved in their children's education (Valencia & Black, 2002).[109] It is important to know that the parents of Mexican American students frequently display their involvement through untraditional methods; such as, consejos, home-base practices, and high academic expectations.

Literature has demonstrated that parental involvement has had a positive influence in the academic achievement of Mexican American students. Studies have shown that Mexican families show their value towards education by using untraditional methods (Kiyama, 2011).[110] One educational practice that is commonly used among Mexican families are consejos (advice). Additional research has supported the idea that parents’ consejos have had a significant influence on the education of Mexican American students. Espino (2016)[111] studied the influence that parental involvement had on seven, 1st generation Mexican American PhDs. The study found that one of the participant's father would frequently use consejos to encourage his son to continue his education. The father's consejos served as an encouragement tool, which motivated the participant to continue his education. Consejos are commonly associated with the parents’ occupation. Parents use their occupation as leverage to encourage their child to continue his or her education, or else they may end up working an undesirable job (Espino, 2016). While this might not be the most common form of parental involvement, studies have shown that it has been an effective tool that encourages Mexican American students. Although that might be an effective tool for Mexican American students, a mother can be just as an important figure for consejos. A mother's role teaches their child the importance of everyday tasks such as knowing how to cook, clean and care for oneself in order to be independent and also to help out around the house. The children of single mothers have a huge impact on their children in pushing them to be successful in school in order to have a better life than what they provided to their children. Most single mothers live in poverty and are dependent of the government, so they want the best for their children so they are always encouraging their children to be focused and do their best.

Another study emphasized the importance of home-based parental involvement. Altschul (2011)[112] conducted a study that tested the effects of six different types of parental involvement and their effect on Mexican American students. The study used previous data from the National Education Longitudinal Study (NELS) of 1988. The data was used to evaluate the influence of parental practices in the 8th grade and their effect on students once they were in the 10th grade. Altschul (2011) noted that home-based parental involvement had a more positive effect on the academic achievement of Mexican American students, than involvement in school organizations. The literature suggests that parental involvement in the school setting is not necessary, parents can impact the academic achievement of their children from their home.

Additional literature has demonstrated that parent involvement also comes in the form of parent expectations. Valencia and Black (2002) argued that Mexican parents place a significant amount of value on education and hold high expectations for their children. The purpose of their study was to debunk the notion that Mexicans do not value education by providing evidence that shows the opposite. Setting high expectations and expressing their desire for their children to be academically successful has served as powerful tools to increase of the academic achievement among Mexican American students (Valencia & Black, 2002). Keith and Lichtman (1995)[113] also conducted a research study that measured the influence of parental involvement and academic achievement. The data was collected from the NELS and used a total of 1,714 students that identified as Mexican American (Chicana/o). The study found a higher level of academic achievement among 8th grade Mexican American students and parents who had high educational aspirations for their children (Keith & Lichtman, 1995).

Additional research done by Carranza, You, Chhuon, and Hudley (2009)[114] added support to the idea that high parental expectations were associated with higher achievement levels among Mexican American students. Carranza et al. (2009) studied 298 Mexican American high school students. They studied whether perceived parental involvement, acculturation, and self-esteem had any effect on academic achievement and aspirations. Results from their study demonstrated that perceived parental involvement had an influence on the students’ academic achievement and aspirations. Additionally, Carranza et al. noted that among females, those who perceived that their parents expected them to get good grades tended to study more and have higher academic aspirations (2009). The findings suggest that parental expectations can affect the academic performance of Mexican American students.

Based on current literature, one can conclude that parental involvement is an extremely important aspect of Mexican American students’ education. The studies demonstrated that parental involvement is not limited to participating in school activities at the school; instead, parental involvement can be displayed through various forms. There are numerous studies that suggest that parental expectations are associated with the achievement level of Mexican American students. Future research should continue to study the reasons why Mexican American students perform better when their parents expect them to do well in school. Furthermore, future research can also look into whether gender influences parental expectations.

Stand and Deliver was an inductee of the 2011 National Film Registry list.[115][116] The National Film Board said that it was "one of the most popular of a new wave of narrative feature films produced in the 1980s by Latino filmmakers" and that it "celebrates in a direct, approachable, and impactful way, values of self-betterment through hard work and power through knowledge."[116]

Mexican American communities

Large Mexican American populations by both size and per capita exist in the following American cities:

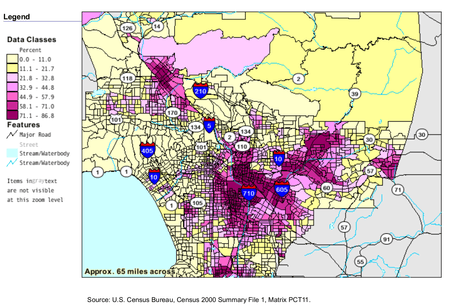

- Los Angeles, California area – the city proper home to over 1.2 million of Mexican ancestry, another 2.3 million throughout Los Angeles County, and a total of about 6.3 million in the five-county Greater Los Angeles Area. Largest Mexican ancestry populated city in the United States. (according to the 2010 census, L.A. is now 31.9% of Mexican descent with numerous Central American national groups).

- East Los Angeles, California – Unincorporated community of roughly 130,000, name synonymous with Mexican Americans, 97% Hispanic, 88% of Mexicans are immigrant, 40% of east L.A. residents reportedly Mexican including American-born.[117]

- Covina, California - 30.69% Mexican

- West Covina, California - 35.41% Mexican

- Montebello, California – Over 62% of the population is Mexican.[118]

- Culver City, California – Also the site of the infamous Zoot Suit Riots in 1943.

- Long Beach, California – Third largest city in Southern California, One of many cities in the region with a large Mexican/Hispanic population.

- South Gate, California – over 70.77% of the population is Mexican or Mexican American.[119]

- La Puente, California – about two-thirds are of Mexican ancestry or Hispanic, one of the largest Hispanic (in percentage, the most Mexican-American community) populations in California.

- Downey, California - Between 45-50% are of Mexican descent.[120]

- Palmdale, California – Over 25.8% of the population is Mexican-American. The city has one of the largest Latino population in the country because of including other Latino groups and Central Americans such as Salvadorans, Guatemalans and Hondurans.[121] Mexicans have traded and lived in the Mojave Desert since early times.[122]

- Compton, California – 48.58% Mexican[123]

- Inglewood, California – 38.73 % Mexican[124]

- El Monte, California – 71.89 % Mexican

- Huntington Park – Large Mexican population

- Cudahy, California – Large Mexican population

- Irwindale, California – Large Mexican population

- Oxnard, California – 65.96 % Mexican

- Inland Empire, California (Riverside/ San Bernardino Counties- and the cities of that namesake) – About a third of the population are of Mexican descent. Including Pomona and Romoland with high Mexican percentages.

- Riverside, California[125], Adelanto, Hesperia, Victorville and Apple Valley in the Victor Valley[126], Rialto and San Bernardino, California[125][127]

- Indio, California[125] and Coachella, California (primarily Mexican-American).[128]

- Santa Ana – 78% Latino with the majority being of Mexican descent.[129]

- Southern California is the highest densely populated Mexican-American region, but by areas of percentage it is South Texas.

- San Diego, California – slightly less than one-third of the city's population is Hispanic, primarily Mexican American; however, this percentage is the lowest of any significant border city.

- Imperial Valley region (Imperial County, California and Yuma, Arizona).

- San Francisco Bay Area – also with over one million Hispanics, many of whom are Mexican Americans, both US-born and foreign-born (see also Oakland about 10–20% Hispanic and San Francisco – the Mission District section- the city is 10–20% Latino).

- Oakland – California's third largest Mexican-American city by percentage (over 25%) after Long Beach (about 30%). Many live in the Fruitvale district.

- San Jose, California – Nearly one-third of the city's population is Mexican-American or of Hispanic origin; San Jose has the largest Mexican-American population within the Bay Area.

- Central Valley of California both the Sacramento and San Joaquin Valleys have majority Mexican American communities. Examples being Sacramento and Fresno, and the heaviest concentrations in Kern County, California around Bakersfield.

- Phoenix, Arizona – fifth largest Mexican-American population.

- Tucson – 30% of the almost 1 million people in the metro area.[130]

- Dallas/Fort Worth Area – fifth largest Mexican-American population and over 1.5 million Mexicans in the Dallas–Fort Worth Metroplex (3rd largest foreign born Mexican population in the US per MSA).

- San Antonio, Texas – over half of the population in the city proper (53.2%, 705,530) and second largest Mexican population of any city in the US.[125]

- Laredo, Texas - has the largest Mexican-American community bordering with Nuevo Laredo, Mexico. The majority of Laredo speaks Spanish as their first language.

- Houston, Texas – Third largest Mexican ancestry community in the United States.[131]

- San Angelo, Texas with other areas of West Texas, home to Tejanos.

- El Paso, Texas – largest Mexican-American community bordering a state of Mexico.

- South Texas – Heavily populated by Mexican-Americans, who are the ethnic majority, in a region spanning from Laredo to Corpus Christi to Brownsville.

- Harlingen, Texas – The Latino population of Harlingen is 72% due to its proximity to the Rio Grande Mexico border.[132]

- Denver, Colorado – Colorado has the eighth largest population of Hispanics, seventh highest percentage of Hispanics, fourth largest population of Mexican-Americans, and sixth highest percentage of Mexican-Americans in the United States. According to the 2010 census, there are over 1 million Mexican-Americans in Colorado.[133] Over one-third of the city's population is Mexican-American or Hispanic/Latino, as well as approximately one-fourth of the entire Denver Metropolitan area. About 17% of the cities population is foreign born, mostly from Latin America.

- Greeley, Colorado – Over one-third of the city's population is Latino, mostly Mexican-American.

- Garden City is Latino majority, and Evans has a very large Latino population as well.

- Southern Colorado is home to many communities of Hispanics descended from Mexican settlers who arrived during Spanish colonial times. Roughly half of Pueblo's population is Latino, mostly Mexican-American. Many other towns in southern Colorado have high proportions of Mexican-Americans. La Junta, Rocky Ford, Las Animas, Lamar, Walsenburg, and Trinidad all have large Mexican American communities.

- San Luis Valley – The San Luis Valley has many towns with large Mexican-American populations. Antonito, Blanca, Center, Del Norte, Fort Garland, Monte Vista, and Romeo are all Latino majority.[134]

- The Yakima Valley and Tri-Cities, Washington – This region of Washington contains many communities of Mexican-American majority thanks to high demand for agricultural labor.

- Chicago – Over 1.5 million of Mexican ancestry in the Chicago metropolitan area[125] and the fourth largest Mexican community in the USA.

Other US destinations

In the 1990s and 2000s, the Midwestern United States became a major destination for Mexican immigrants. But Mexican-Americans were already present in the Midwest's industrial cities and urban areas. Especially Mexicans/Latinos came into states like Illinois (mostly in Chicago and close-in suburbs), Indiana especially the Northern section, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan (Especially in the Western Portion of the state.), Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska and Wisconsin due to needs of the region's industrial manufacturing base.

Another destination of Mexican and Latin American immigration was the Northeastern United States, in places such as the Monongahela Valley, Pennsylvania; Mahoning Valley, Ohio; throughout Massachusetts and the state of Rhode Island; New Haven, Connecticut along with other Latin American nationalities; Washington, D.C. with Maryland and Northern Virginia included; the Hudson Valley and Long Island of New York state; the Jersey Shore region and the Delaware Valley, New Jersey.

Communities that consist mostly of recent-arrived immigrants from Mexico, other than Texas, are also present in other parts of the rural Southern United States, in states such as Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Oklahoma, Arkansas, South Carolina and Alabama. A growing Mexican-American population is also present in urban areas such as Orlando, Florida, Tampa, Florida with the Central Florida region included; the Atlanta metro area; Charlotte, North Carolina- with a majority Hispanic enclave of Eastland; New Orleans which increased after Hurricane Katrina in Sep. 2005; the Hampton Roads, Virginia area; the states of Maine, New Hampshire and Delaware; and Pennsylvania especially in the Philadelphia metropolitan area.

Major cities like Boise, Idaho; Detroit, Michigan; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Portland, Oregon; Salt Lake City, Utah; and Seattle, Washington have a large Mexican-American population.[135]

U.S. states by Mexican American population

| State/Territory | Mexican American Population (2020)[136] | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 124,210 | 2.6 | |

| 28,049 | 3.8 | |

| 1,926,274 | 27.8 | |

| 159,273 | 5.4 | |

| 12,621,844 | 32.3 | |

| 869,149 | 15.8 | |

| 57,383 | 1.6 | |

| 34,244 | 3.7 | |

| 14,146 | 1.6 | |

| 713,518 | 3.5 | |

| 561,710 | 5.5 | |

| 45,832 | 3.3 | |

| 181,185 | 10.8 | |

| 1,715,831 | 13.4 | |

| 333,219 | 5.1 | |

| 143,368 | 4.6 | |

| 278,213 | 9.6 | |

| 89,217 | 2.1 | |

| 93,750 | 2.1 | |

| 6,251 | 0.5 | |

| 97,231 | 1.7 | |

| 47,911 | 0.7 | |

| 363,421 | 4.9 | |

| 201,580 | 3.7 | |

| 56,282 | 1.9 | |

| 172,055 | 2.9 | |

| 27,510 | 2.7 | |

| 150,424 | 7.9 | |

| 629,469 | 21.6 | |

| 8,686 | 0.7 | |

| 230,875 | 2.6 | |

| 658,516 | 31.5 | |

| 477,194 | 2.5 | |

| 538,505 | 5.3 | |

| 17,915 | 2.3 | |

| 200,060 | 1.8 | |

| 333,166 | 8.5 | |

| 431,169 | 10.6 | |

| 152,537 | 1.2 | |

| 11,123 | 1.1 | |

| 150,582 | 3.1 | |

| 21,229 | 2.5 | |

| 217,557 | 3.3 | |

| 9,394,506 | 33.7 | |

| 306,375 | 10.7 | |

| 3,335 | 0.6 | |

| 173,046 | 2.1 | |

| 728,208 | 10.0 | |

| 10,982 | 0.6 | |

| 278,789 | 4.9 | |

| 44,704 | 7.7 | |

| Total US | 36,600,000 | 12.2 |

Health

Diabetes

Diabetes refers to a disease in which the body has an inefficiency of properly responding to insulin, which then affects the levels of glucose. The prevalence of diabetes in the United States is constantly rising. Common types of Diabetes are type 1 and type 2. Type 2 is the more common type of diabetes among Mexican Americans, and is constantly increasing due to poor diet habits.[137] The increase of obesity results in an increase of type 2 diabetes among Mexican Americans in the United States. Mexican American men have higher prevalence rates in comparison to non-Hispanics, whites and blacks.[138] “The prevalence of diabetes increased from 8.9% in 1976–1980 to 12.3% in 1988–94 among adults aged 40 to 74” according to the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994.[138] In a 2014 study, The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that by 2050, one in three people living in the United States will be of Hispanic/Latino origin including Mexican Americans.[139] Type 2 diabetes prevalence is rising due to many risk factors and there are still many cases of pre-diabetes and undiagnosed diabetes due to lack of sources. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2011), individuals of Mexican descent are 50% more likely to die from diabetes than their white counterparts.[138]

Notable people

See also

- American immigration to Mexico

- Mexico–United States relations

- Hyphenated American

- Mexicans abroad

- Mexican cuisine

- Mexican people

- Tex-Mex cuisine

Ethnic:

- Melting pot (metaphor for cultural fusion)

- Amerindian

- White Hispanic and Latino Americans

- White Mexican

- Olive skin

- Mestizo

- Bronze race

- Cosmic race

- Brown race

- Mestizos in the United States

Political:

Cultural:

- Chicanismo

- Chicano poetry

- List of Mexican American writers

- El Pueblo de Los Ángeles Historical Monument

Film:

References

- "B03001 HISPANIC OR LATINO ORIGIN BY SPECIFIC ORIGIN - United States - 2018 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. July 1, 2018. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242491308_Demographic_Profile_of_Mexican_Immigrants_in_the_United_States

- Cohen, Saul Bernard (25 November 2014). Geopolitics: The Geography of International Relations. ISBN 9781442223516.

- https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/mexican-immigrants-united-states-2

- https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/mexican-immigrants-united-states

- https://books.google.com/books?id=6qnuDQAAQBAJ&pg=PA53&dq=Mexican+Americans+live+in+rural+suburban+areas&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwj8xY3wjJDqAhW2HzQIHVt6CCEQ6AEILTAB#v=onepage&q=Mexican%20Americans%20live%20in%20rural%20suburban%20areas&f=true

- Donoso, Juan Carlos. On religion, Mexicans are more Catholic and often more traditional than Mexican Americans.

- "Table 4. Top Five States for Detailed Hispanic or Latino Origin Groups With a Population Size of One Million or More in the United States: 2010" (PDF). The Hispanic Population 2010. US Census Bureau. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- Number of Mexican Immigrants and Their Share of the Total U.S. Immigrant Population, 1850-2017, Migration Policy Institute

- "National Household Survey (NHS) Profile, 2011". 2.statcan.gc.ca. 2013-05-08. Retrieved 2014-03-24.

- Mexican Americans – MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on November 1, 2009.

- Gomez, Laura E. Manifest Destinies. NYU Press.

- U.S. Congress. Recommendation of the Public Land Commission for Legislation as to Private Land Claims, 46th Congress, 2nd Session, 1880, House Executive Document 46, pp. 1116–17.

- Mexicanos: A history of Mexicans in the United States. Manuel G. Gonzales, Indiana University Press P.86-87 ISBN 0-253-33520-5

- The U.S.-Mexico Border: The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, John C. Davenport, P.48, ISBN 0-7910-7833-7

- Rosales, F. Arturo (2007-01-01). "Repatriation of Mexicans from the US". In Soto, Lourdes Diaz (ed.). The Praeger Handbook of Latino Education in the U.S. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 400–403. ISBN 9780313338304.

- Johnson, Kevin (Fall 2005). "The Forgotten Repatriation of Persons of Mexican Ancestry and Lessons for the War on Terror". 26 (1). Davis, CA: Pace Law Review.

- Hoffman, Abraham (1974-01-01). Unwanted Mexican Americans in the Great Depression: Repatriation Pressures, 1929-1939. VNR AG. ISBN 9780816503667.

- Balderrama, Francisco E.; Rodriguez, Raymond (2006-01-01). Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 9780826339737.

- "Meet the 20 MAKERS Inducted Into the National Women's Hall of Fame". Makers. October 5, 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- "Dolores Huerta". The Adelante Movement. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- Villarreal, Andrés (December 2014). "Explaining the Decline in Mexico-U.S. Migration: The Effect of the Great Recession". Demography. 51 (6): 2203–2228. doi:10.1007/s13524-014-0351-4. ISSN 0070-3370. PMC 4252712. PMID 25407844.

- Department of Homeland Security: "2015 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics" 2015

- "U.S. State Department: "Annual Report of Immigrant Visa Applicants in the Family-sponsored and Employment-based preferences Registered at the National Visa Center as of November 1, 2016" (PDF). Travel.state.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- Population Reference Bureau (2013-11-13). "Latinos and the Changing Face of America – Population Reference Bureau". Prb.org. Archived from the original on 2012-05-19. Retrieved 2014-01-06.