Haida people

Haida (English: /ˈhaɪdə/, Haida: X̱aayda, X̱aadas, X̱aad, X̱aat) are a nation and ethnic group native to, or otherwise associated with, Haida Gwaii (an archipelago located off the west coast of Canada and immediately south of Alaska) meaning "Coming out of concealment" or sometimes "island of the People", and the Haida language. The Haida language is an isolate language, that has been spoken historically across Haida Gwaii and other islands on the Alaska Panhandle. Prior to the 19th century, Haida spoke a number of coastal First Nations languages such as Tlingit, Nisg̱a'a and Coast Tsimshian. This resulted in a sudden decline in its usage throughout the 1900s. Haida language champions are working through multiple initiatives to revitalize the Haida language along with Haida law, customs, and cultural identity.

X̱aayda, X̱aadas, X̱aad, X̱aat | |

|---|---|

Flag of the Council of the Haida Nation (CHN) | |

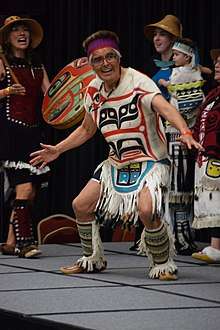

Haida artist Robert Davidson dancing in full regalia. | |

| Total population | |

| c. 3,500+[1] | |

| Canada | 3,471[1] |

| United States | unknown |

| Languages | |

| Haida, English | |

| Religion | |

| Haida, possibly Christianity and others | |

In Haida Gwaii, the Haida government consists of a matrix of national and regional hereditary, legislative, and executive bodies including the Hereditary Chiefs Council, the Council of the Haida Nation (CHN), Old Massett Village Council, Skidegate Band Council, and the Secretariat of the Haida Nation. These are based in the archipelago of Haida Gwaii (formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands) outside the territorial seas of Canada off of northern British Columbia, Canada. The Kaigani Haida live north of the Canadian and US border which cuts through the Dixon Entrance on Prince of Wales Island (Tlingit: Taan) in Southeast Alaska, United States; Haida from Kiis Gwaii in the Duu Guusd region of the Haida Gwaii migrated north in the early 1700s. Following the accidental death of a Haida by a Tlingiit the Haida were formally given territories by the Tlingiit governments. Haida have occupied Haida Gwaii since at least 14,000 BP, and evidence has shown that there has been constant habitation on the islands for at least 6000 years. Pollen fossils and oral histories both confirm that Haida ancestors were present when the first tree, a Lodgepole pine, arrived at SG̱uuluu Jaads Saahlawaay, the westernmost of the Swan Islands located in Gwaii Haanas.[2]

Canada's reconciliation movement is a relatively recent development. For example, after years of claiming the islands were actually the Queen Charlotte Islands, British Columbia announced in December 2009 that provincial legislation would be implemented to rename the archipelago to Haida Gwaii in recognition of the Haida people. The Haida Nation asserts Haida title over all of Haida Gwaii, and is pursuing negotiations with the provincial and federal governments. Haida authorities continue to pass legislation and manage human activities in Haida Gwaii, which includes making formal agreements with the Canadian communities established on the islands. Haida efforts are largely directed to the protection of land and water and functioning ecosystems and this is expressed in the protected status for nearly 70% of the million hectare archipelago. The protected status applies to the landscape and water as well as smaller culturally significant areas. They have also forced a reduction of large scale industrial activity and the careful regulation of access to resources. In the fall of 2019 with both the Provincial and Federal Crown in minority government there are indications that the reconciliation of Canada and Indigenous titles may resume.

History

Haida history begins with the arrival of the primordial ancestresses of the Haida matrilineages in Haida Gwaii some 14,000 to 19,000 years ago. These include SGuuluu Jaad (Foam Woman), Jiila Kuns (Creek Woman), and KalGa Jaad (ice woman). The Haida canon of oral histories and archeological findings agree that Haida ancestors lived alongside glaciers and were present at the time of the arrival of the first tree, a lodgepole pine, in Haida Gwaii. For thousands of years since Haida have participated in a rigorous coast-wide legal system called Potlatch. After the Islands wide arrival of red cedar some 7,500 years ago Haida society transformed to centre around the coastal "tree of life". Massive carved cedar monuments and cedar big houses became widespread throughout Haida Gwaii.

The first recorded European contact was in 1774 with Spanish explorer Juan Perez. However, some academics believed that there was contact prior to that with Russian explorers as early as 1741 and even earlier with Spanish ships originating from the west coast of Mexico in the 1500s. The name of a principle village Massett is actually a Spanish surname and was gifted by a damaged sailing ship rescued and repaired with the help of Auuxaada (Haida villages located along the mouth of Massett Inlet).

Haida Gwaii's pre-contact population was estimated towards the tens of thousands by the Council of the Haida Nation. A similar estimate was recorded by early fur traders. The Haida used large canoes to navigate, trade and even raid all along the west coast of Canada. Although they had gone on expeditions as far south as California and across the Pacific, confrontations were minimal. European transgressions of Haida law such as attempts to mine gold were responded to with appropriate force by Haida authorities. Despite this, smallpox introduction first by Russian and then intentionally by Canadians resulted in population loss over three plagues finally down to 588 people by 1915. It was not until then that European settlers were confident enough to settle on Haida Gwaii. Over time Europeans increasingly infringed on Haida territories. In 1911 Canada and British Columbia rejected a Haida offer whereby in exchange for full rights of British citizenship Haidas would formally join the Dominion. Haida people then gathered in two communities and armoured themselves against the intrusion of foreign people and policy. The Canadian policy was prolonged and expansive and included seizing children into residential schools located thousands of kilometres away from Haida Gwaii. Such efforts to erode Haida authority were never fully successful. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada was officially launched in 2008 with a plan to help people by exposing the terrible information about the system that residential schools were a part of and in hopes of working toward reconciliation throughout Canada.

Some of the things that living Haida are known for is political resilience. This persistent expression is also seen in their assertive and direct approach causing anthropologist Diamond Jenness to compare them to Vikings. The coastal raiding activities in specialized ocean-going vessels also parallel cultural traditions of Viking culture.

In British Columbia, the term "Haida Nation" often refers to Haida people as a whole however, it also refers to their government, the Council of the Haida Nation. While all people of Haida ancestry are entitled to Haida citizenship, including the Kaigani who as Alaskans are also part of the Central Council Tlingit Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska government.[3][4] The Haida language has sometimes been classified as one of the Na-Dene group, but is usually considered to be an isolate.[5] In spite of the de facto banning of the Haida language with the introduction of residential schools and the enforcement of the use of English language, Haida language revitalization projects swung into action in the 1970s and continue to this day. It is estimated that there are only 3 or 4 dozen Haida speaking people with almost all of them being the age of 70 or older.

Haida society continues to produce a robust and highly stylized art form, a leading component of Northwest Coast art. While artists frequently have expressed this in large wooden carvings (totem poles), Chilkat weaving, or ornate jewellery, in the 21st century, younger people are also making art in popular expression such as Haida manga.

In 2018 the first feature-length Haida-language film, The Edge of the Knife (Haida: SG̲aawaay Ḵʹuuna), was released, with an all-Haida cast. The actors learned Haida for their performances in the film, with a 2-week training camp followed by lessons throughout the 5 weeks of filming. Haida artist Gwaai Edenshaw and Tsilhqot'in filmmaker Helen Haig-Brown directed, with Edenshaw and his brother being co-screenwriters, with Graham Richard and Leonie Sandercock.[6]

In spring 2020, "Now is the Time", a documentary by Haida Film maker Christopher Auchter was selected to screen at Sundance film festival.

Culture and religion

Many Haida believe in an ultimate being called Ne-kilst-lass which can be expressed through the form and antics of a Raven. Ne-kilst-lass revealed the world and was an active player in the creation of life. Although Ne-kilst-lass has a generous inclination it also includes a darker, indulgent and trickster quality.

Potlatches

Haida host Potlatches which were intricate economic and social political processes that include acquisition of incorporeal wealth like names and the circulation of property in the form of gifts. They are often held when a citizen wishes to commemorate an event of importance. For example, deaths of a loved one, marriages, and other civil proceedings. The more important potlatches take years to prepare and can continue for days.

Not commonly applied today but young boys and girls entering puberty would embarked on vision quests. These quests would send them out alone for days, they would travel through the forests, in hopes of finding a spirit to guide them through their lives. There were unique spirits for boys and girls who were to become great. A successful vision quest was celebrated by the wearing of masks, face paints, and costumes.

Transformation masks

Transformation masks were worn ceremonially, used by dancers and represented or illustrated the connection between various spirits. The masks usually depicted an animal transforming into another animal or a spiritual or mythical being. Masks were representations of the souls of the mask owner's family waiting in the afterlife to be reborn. Masks worn during ceremonial dances were designed with strings to open the mask, transforming the spiritual animal into a carving of the ancestor underneath. There was also emphasis on the idea of metamorphosis and reincarnation. With the banning of potlatches by the Canadian government in 1885, many masks were confiscated. Masks and many other objects are considered sacred and designed only for specific people to see. It was unknown who the wearer of the mask was as each mask was made for each individual's soul and spirit animal. Due to the confiscation of the masks and the sacred meaning to each individual who wore the mask, it is unknown if the masks in museums are truly meant to be seen or if they are an aspect of European colonialism and the rejection of Haida religious and spiritual traditions.

Family

The traditional society of the Haida people had many villages that linked related families. The Haida followed a matrilineal descent that consisted of a mother and her children, her daughter's children and her granddaughter's children, etc.

Social structure

The Haida social structure before contact was one that is worth noting. The Haida nation was split between two social groups or moieties, the Raven and the Eagle. Between these two social groups marriages would be exchanged between the two tribes as it was enforced that the marriages between two people from the same moiety were prohibited. Due to this any children that were born after the marriage would officially become part of the moiety that the mother had come from. For example, if the father is from the Eagle social group and the mother is from the Raven social group their children would automatically be a part of the Raven moiety. Each group provided its members with entitlement to a vast range of economic resources such as fishing spots, hunting or collecting areas, and housing sites. Each group also had rights to their own myths and legends, dances, songs, and music. Eagles and Ravens were very important to the Haida families as they would identify with one or the other and this would signify what side on the village they would reside on. The family would also own their own property, had specific areas for food gathering. These categories of Eagles and Ravens divided them on an even larger scale, specifying their land, history, and customs. The roles of the family varied between men and women. Men were responsible for all of the hunting and fishing, building home and carving canoes and totem poles. The women's responsibilities were to stay close to home doing a majority of their work on the land. Women were responsible for all of the chores in relation to the keeping of the home. Women were also in charge of curing cedarwood to use for weaving and making clothes. It was also the duty of the women to gather berries and dig for shellfish and clams.

The Haida social system changed significantly by the end of the nineteenth century. At this point a majority of the Haida had taken nuclear family forms, and members of families belonging in the same moiety (Ravens and Eagles) were permitted to marry each other, which was previously forbidden.

Maturity and coming of age

Once a boy hit puberty, their uncles on their mothers’ side would educate them on their family history and how to behave now that they were a man. It was believed that a special diet would increase his abilities. For example, duck tongues helped him hold his breath under water, whereas blue jay tongues helped him to be a strong climber.

The aunts on the father's side of a young Haida woman would teach her about her duties to her tribe once she first began to menstruate. The young woman would go to a secluded space in her family home. They believed that by making her sleep on a stone pillow and only allowing her to eat and drink small amounts she would become tougher.

History

The Haida are known for their craftsmanship, trading skills, and seamanship. They are thought to have been warlike and to practise slavery. Anthropologist Diamond Jenness has compared the Haida to Vikings while Haida have replied saying that Vikings are like Haida.[7]

The Haida conducted regular trade with Russian, Spanish, British, and American fur traders and whalers. According to sailing records, they diligently maintained strong trade relationships with Westerners, coastal people, and among themselves.[8] Trade for sea-otter pelts was initiated by British Captain George Dixon with the Haida in 1787. The Haida did well for themselves in this industry and until the mid-1800s they were at the centre of the profitable China sea-otter trade.

Like other groups on the Northwest Coast, the Haida defended themselves with fortifications, including palisades, trapdoors and platforms. The Haida were known to go to war with other Indigenous nations. They took to water in large ocean-going canoes, each created from a single Western red cedar tree, and big enough to accommodate as many as 60 paddlers. The aggressive tribe were particularly feared in sea battles, although they did respect rules of engagement in their conflicts.[7] The Haida developed effective weapons for boat-based battle, including a special system of stone rings weighing 18 to 23 kg (40 to 51 lb) which could destroy an enemy's dugout canoe and be reused after the attacker pulled it back with the attached cedar bark rope. The Haida took captives from defeated enemies, however the Haida also owned slaves, who were war captives or the children of captives. Although they had gone on expeditions as far as Washington State, at first they had minimal confrontations with Europeans. Despite this between 1780 and 1830, the Haida turned their aggression towards European and American traders. Among the dozens ships the tribe captured were the Eleanor and the Susan Sturgis. The tribe made use of the weapons they so acquired, using cannons and canoe-mounted swivel guns.[7]

In 1856, an expedition in search of a route across Vancouver Island was at the mouth of the Qualicum River when they observed a large fleet of Haida canoes approaching and hid in the forest. They observed these attackers holding human heads. When the explorers reached the mouth of the river, they came upon the charred remains of the village of the Qualicum people and the mutilated bodies of its inhabitants, with only one survivor, an elderly woman, hiding terrified inside a tree stump.[9]

Due to smallpox and other diseases brought over by the Europeans resulted in their population dropping to 588 people by 1915. It was not until nearly the 1900s that the European settlers drastically populated Haida Gwaii. Over time Europeans increasingly infringed on Haida territories and eventually the Haida had no choice but to move onto smaller parcels of land.

Also in 1857, the USS Massachusetts was sent from Seattle to nearby Port Gamble, where indigenous raiding parties made up of Haida (from territory claimed by the British) and Tongass (from territory claimed by the Russians) had been attacking and enslaving the Coast Salish people there. When the Haida and Tongass (sea lion tribe Tlingit) warriors refused to acknowledge American jurisdiction and to hand over those among them who had attacked the Puget Sound communities, a battle ensued in which 26 natives and one government soldier were killed. In the aftermath of this, Colonel Isaac Ebey, a US military officer and the first settler on Whidbey Island, was shot and beheaded on 11 August 1857 by a small Tlingit group from Kake, Alaska, in retaliation for the killing of a respected Kake chief in the raid the year before. Ebey's scalp was purchased from the Kake by an American trader in 1860.[10][11][12][13] The introduction of smallpox among the Haida at Victoria in March 1862 significantly reduced their sovereignty over their traditional territories, and opened the doorway to colonial power.[14] As many as nine in ten Haidas died of smallpox and many villages were completely depopulated.

In 1885 the Haida potlatch (Haida: waahlgahl) was outlawed under the Potlatch Ban. The elimination of the potlatch system destroyed financial relationships and seriously interrupted the cultural heritage of coastal people.

The Haida also created "notions of wealth", and Jenness credits them with the introduction of the totem pole (Haida: ǥyaagang) and the bentwood box.[7] Missionaries regarded the carved poles as graven images rather than representations of the family histories that wove Haida society together. Chiefly families showed their histories by erecting totems outside their homes, or on house posts forming the building. Their social organization was matrilineal.[15] As the islands were Christianized, many cultural works such as totem posts were destroyed or taken to museums around the world. This significantly undermined Haida self-knowledge and further diminished morale.

The government began forcibly sending some Haida children to residential schools as early as 1911. Haida children were sent as far away as Alberta to live among English-speaking families where they were to be assimilated into the dominant culture.

Historical warfare

Prior to contact with Europeans, other Indigenous communities regarded the Haida as aggressive warriors and made attempts to avoid sea battles with them. Archeological evidence shows that Northwest coast tribes, to which the Haida belong, engaged in warfare as early as 10 000 BC.[16] Though the Haida were more likely to participate in sea battles, it was not uncommon for them to engage in hand-to-hand combat or long-range attacks. Hostilities were not always violent, often ritualized and some resulting in Peace Treaties still in force hundreds of years later.

Archeological and written evidence of warfare

Analyses of skeletal injuries dating from the Archaic period show that Northwest coast nations, particularly in the North where most Haida communities were situated, engaged in battles of some sort, though the number of battles is unknown.[16] The presence of defensive fortifications dating from the Middle Pacific period show that the incidence of battles rose somewhere between 1800 BC and AD 500.[16] These fortifications continued to be in use during the 18th century as evidenced by Captain James Cook’s discovery of one such hilltop fortification in a Haida village. Numerous other sightings of such fortifications were recorded by other European explorers during this century.[17]

Causes of warfare

There were multiple reasons that motivated Haida people to commit warfare. Various accounts explain that the Haida went to battle more for revenge and slaves than for anything else.[18] According to the anthropologist Margaret Blackman, who has done research on the Haida since the 1970s, warfare on Haida Gwaii was primarily motivated by revenge. Many Northwest coast legends tell of Haida communities raiding and fighting with neighbouring communities because of insults.[19] Other causes included disputes over property, territory, resources, trade routes and even women. However, a battle between a Haida community and another often did not have simply one cause. In fact, many battles were the result of decades old disputes.[20] The Haida, like many of the Northwest coast Indigenous communities, engaged in slave-raiding as slaves were highly sought after for their use as labour as well as bodyguards and warriors.[21] During the 19th century, the Haida fought physically with other Indigenous communities to ensure domination of the fur trade with European merchants.[22] Haida groups also had feuds with these European merchants that could last years. In 1789, some Haidas were accused of stealing items from Captain Kendrick, most of which included drying linen. Kendrick seized two Haida chiefs and threatened to kill them via cannon-fire if they did not return the stolen items. Though the Haida community complied at the time, less than two years later 100 to 200 of its people attacked the same ship.[23]

War parties

The missionary W. H. Collison describes having seen a Haida fleet of around forty canoes.[24] However, he does not provide the number of warriors in these canoes, and there are no other known accounts that describe the number of warriors in a war party. The structure of a Haida war party generally followed that of the community itself, the only difference being that the chief took the lead during battles; otherwise his title was more or less meaningless.[25] Medicine men were often brought along raids or before battles to “destroy the souls of enemies” and ensure victory.[26]

Death in battle

Battles between a group of Haida warriors and another community sometimes resulted in the annihilation of either one or both of the groups involved.[27] Villages would be burned down during a battle which was a common practice during Northwest coast battles.[27] The Haida burned their warriors who died in battles, though it is not known if this act was done after each battle or only after battles in which they were victorious.[28] The Haida believed that fallen warriors went to the House of Sun, which was considered a highly honourable death. For this reason, a specially made military suit for chiefs was prepared if they fell in battle. The slaves belonging to the chiefs who died in battle were burned with them.[28]

Weapons used in battles

The Haida used the bow and arrow until it was replaced by firearms acquired from Europeans in the 19th century, but other traditional weapons were still preferred.[29] The weapons that the Haida used were often multi-functional; they were used not only in battle, but during other activities as well. For instance, daggers were very common and almost always the weapon of choice for hand-to-hand combat, and were also used during hunting and to create other tools. One medicine man's dagger that Alexander Mackenzie came across during his exploration of Haida Gwaii, was used both for fights and to hold the medicine man's hair up.[30] Another dagger that Mackenzie obtained from a Haida village was said to be connected to a Haida legend; many daggers had individual histories which made them unique from one another.[30]

Battle armour

The Haida wore rod-and-slat armour. This meant greaves for the thighs and lower back and slats (a long strip of wood) in the side pieces to allow for more flexibility during movement. They wore elk hide tunics under their armour and wooden helmets. Arrows could not penetrate this armour, and Russian explorers found that bullets could only penetrate the armour if shot from a distance of less than 20 feet. The Haida rarely used shields because of their developed armour.[31]

Villages

Historical Haida villages were:[32]

- Kiusta

- Kung

- Yan

- Hiellan

- Skidegate (Graham Island)

- Cha'atl

- Haina

- Kaisun (Haida: Ḵaysuun Llnagaay[33])

- Cumshewa (Moresby Island)

- Skedans aka Koona or Q'una.

- Tanu (New Clew), Louise Island

- Ninstints (Sgang Gway, aka Anthony Island)

- Masset The name Masset, received from pre British contact between Haidas and the Spanish, actually includes three separate and adjoining communities,

- Atewaas (Old Massett)

- Jaahguhl

- Kayung

- Hlk'yah GaawGa (Windy Bay) (Lyell Island)[34]

- Klinkwan (Kaigani Haida, Prince of Wales Island)

- Sukkwan (Kaigani Haida, Prince of Wales Island)

- Howkan (Kaigani Haida, Prince of Wales Island)

- Kasaan (Kaigani Haida, Prince of Wales Island)

- Tlell, British Columbia

- Dadens, Langara Island

Calendar

The Haidas' calendar:

- April/May- Gansgee 7laa kongaas

- May/Early June- Wa.aay gwaalgee

- June/July- Kong koaas

- July/August- Sgaana gyaas

- August/September- K'ijaas

- September/October- K'alayaa Kongaas

- October/November- K'eed adii

- November/December- Jid Kongaas

- December/January- Kong gyaangaas

- January/February- Hlgiduum kongaas

- February/March- Taan kongaas

- March- Xiid gayaas

- April- Wiid gyaas

Ethnobotany

They use the berries of Vaccinium vitis-idaea ssp. minus as food.[35]

Notable Haida

- Primrose Adams, artist

- Delores Churchill, artist, basketweaver

- Marcia Crosby, art historian

- Cumshewa, chief

- Florence Davidson, artist and memoirist

- Reg Davidson, carver

- Robert Davidson, carver

- Freda Diesing, carver

- Charles Edenshaw, carver, jeweler and painter

- Gidansda Guujaaw (Gary Edenshaw), artist and politician, former President of the Council of the Haida Nation

- Dorothy Grant, artist, fashion designer

- Jim Hart, hereditary chief of Stasstas Eagle Clan, artist

- Koyah, chief

- Gerry Marks, artist

- Bill Reid, carver, sculptor and jeweler

- Jay Simeon, artist

- Skaay, historian and storytelling expert

- Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas, artist

- Gidansda KalGa (Percy Williams), hereditary leader of Gak'yals KiiGaawaay and one of the founders of the Council of the Haida Nation

Anthropologists and scholars

This is an incomplete list of anthropologists and scholars who have done research on the Haida.

- Marius Barbeau

- Franz Boas

- Robert Bringhurst

- Emily Carr

- Gillian Crowther

- Kathleen E. Dalzell

- Wilson Duff

- John Enrico

- Daryl Fedje

- Christie Harris

- Bill Holm

- Robert Bruce Inverarity

- Marianne Boelscher Ignace

- Clealls John Medicine Horse Kelly

- George Peter Murdock

- Charles F. Newcombe

- Frances Poole

- Mary Lee Stearns

- John R. Swanton

- Elvira Stefania Tiberini

- Nancy J. Turner

- Dan Vaughan

- Frederick White

See also

References

- History of the Haida Nation, Council of the Haida Nation website. Skidegate and Old Masset are 1,471 combined, and 2,000 more Haida live in Vancouver and Prince Rupert and elsewhere.

- Fedje, Daryl (2005). Haida Gwaii: Human History and Environment from the Time of Loon to the Time of the Iron People (1 ed.). UBC Press. p. 128. ISBN 9780774809221. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- "Constitution of the Haida Nation" (PDF). Council of the Haida Nation. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- "Central Council Tlingit Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska". Retrieved 2016-06-23.

- Schoonmaker, Peter K.; Bettina von Hagen; Edward C. Wolf (1997). The Rain Forests of Home: Profile of a North American Bioregion. Island Press. p. 257. ISBN 1-55963-480-4.

- Porter, Catherine (12 June 2017). "A Language Nearly Lost is Revived in a Script". The New York Times. p. 1.

- "Warfare". Canadian Museum of Civilization. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- "Canoes and Trade". Canadian Museum of History. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- Elms p 20, citing William Wyford Walkem, Stories of Early British Columbia, "Adam Horne's trip across Vancouver Island" (Vancouver, BC: Published by News Advertiser, 1914) p 41.

- Puget Sound Herald Nov 19, 1858

- Juneau Empire, February 29, 2008

- Beth Gibson, Beheaded Pioneer, Laura Arksey, Columbia, Washington State Historical Society, Tacoma, Spring, 1988.

- Bancroft says they were Stikines and makes no mention of the Haida. History of Washington, Idaho, and Montana: 1845–1889, p.137 Hubert Howe Bancroft (1890) This enormous source, photocopied, including p.137, is more easily accessible online at , if desired. Retrieved 2012-2-21.

- "The Spirit of Pestilence". The University of Victoria. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- "Social Organization". Canadian Museum of History. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- Ames, Kenneth M.; Maschner, Herbert D. G. (1999). Peoples of the northwest coast: their archaeology and prehistory. London: Thames & Hudson, p. 200-201.

- Jones, David E. (2004). Native North American armor, shields, and fortifications (1st ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press, p. 101.

- Ames, Kenneth M.; Maschner, Herbert D. G. (1999). Peoples of the northwest coast: their archaeology and prehistory. London: Thames & Hudson, p. 196.

- Swanton, John Reed (1905). Haida texts and myths, Skidegate dialect;. Harvard University. Washington, Govt. print. Off., p. 371-390.

- Collison, W. H.; Lillard, Charles (1981). In the wake of the war canoe: a stirring record of forty years' successful labour, peril, and adventure amongst the savage Indian tribes of the Pacific coast, and the piratical head-hunting Haida of the Queen Charlotte Islands, British Columbia. Victoria, B.C: Sono Nis, p. 138.

- Ames, Kenneth M. (2001). "Slaves, Chiefs and Labour on the Northern Northwest Coast". World Archaeology 33 (1): 1–17., p. 3.

- Gibson, James (1992). Otter Skins, Boston Ships, and China Goods: The Maritime Fur Trade of the Northwest Coast, 1785-1841 (First Edition). Montreal: Mcgill-Queens University Press, p. 174.

- Gibson, James (1992). Otter Skins, Boston Ships, and China Goods: The Maritime Fur Trade of the Northwest Coast, 1785-1841 (First Edition). Montreal: Mcgill-Queens University Press, p. 165-166.

- Collison, W. H.; Lillard, Charles (1981). In the wake of the war canoe: a stirring record of forty years' successful labour, peril, and adventure amongst the savage Indian tribes of the Pacific coast, and the piratical head-hunting Haida of the Queen Charlotte Islands, British Columbia. Victoria, B.C: Sono Nis, p. 89.

- Green, Jonathan S. (1915). Journal of a tour on the north west coast of America in the year 1829, containing a description of a part of Oregon, California and the north west coast and the numbers, manners and customs of the native tribes. New York city: Reprinted for C. F. Heartman, p. 45.

- Jenness, Diamond (1977). The Indians of Canada (7th ed.). Toronto; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, p. 333.

- Harrison, C. (1925). Ancient warriors of the north Pacific: the Haidas, their laws, customs and legends, with some historical account of the Queen Charlotte Islands. London: H. F. & G. Witherby, p. 153.

- Green, Jonathan S. (1915). Journal of a tour on the north west coast of America in the year 1829, containing a description of a part of Oregon, California and the north west coast and the numbers, manners and customs of the native tribes. New York city: Reprinted for C. F. Heartman, p. 47.

- "Civilization.ca - Haida - Haida villages - Warfare". www.historymuseum.ca. Retrieved 2018-11-29.

- Mackenzie, Alexander; Dawson, George Mercer (1891). Descriptive notes on certain implements, weapons, &c., from Graham Island, Queen Charlotte Islands, B.C. CIHM/ICMH Microfiche series. Royal Society of Canada, p. 50-51.

- Jones, David E. (2004). Native North American armor, shields, and fortifications (1st ed.). Austin: University of Texas Press, p. 106-107.

- Canadian Museum of Civilization webpage on Haida villages

- "FirstVoices: Hlg̱aagilda X̱aayda Kil : words". Retrieved 2012-07-08.

- Parks Canada website Archived 2013-01-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Compton, Brian Douglas, 1993, Upper North Wakashan and Southern Tsimshian Ethnobotany: The Knowledge and Usage of Plants..., Ph.D. Dissertation, University of British Columbia, page 101

General sources

- Macnair, Peter L.; Hoover, Alan L.; Neary, Kevin (1981). The Legacy: Continuing Traditions of Canadian Northwest Coast Indian Art

Further reading

- Blackman, Margaret B. (1982; rev. ed., 1992) During My Time: Florence Edenshaw Davidson, a Haida Woman. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Boelscher, Marianne (1988) The Curtain Within: Haida Social and Mythical Discourse. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

- Bringhurst, Robert (2000) A Story as Sharp as a Knife: The Classical Haida Mythtellers and Their World. Douglas & McIntyre.

- Donald, Leland (1997) Aboriginal Slavery on the Northwest Coast of North America. University of California Press.

- Andersen, Doris (1974) Slave of the Haida. Macmillan Co. of Canada.

- Kushner, Howard (1975) Conflict on the Northwest Coast: American-Russian Rivalry in the Pacific Northwest. Greenwood Press.

- Black, Lydia T.; Dauenhauer, Nora; Dauenhauer, Richard (2008), Anóoshi Lingít Aaní Ká/Russians in Tlingit America: The Battles of Sitka, 1802 and 1804, University of Washington Press, ISBN 978-0-295-98601-2.

- Fisher, Robin (1992) Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774-1890. UBC Press.

- Geduhn, Thomas (1993) "Eigene und fremde Verhaltensmuster in der Territorialgeschichte der Haida." (Mundus Reihe Ethnologie, Band 71.) Bonn: Holos Verlag.

- Harris, Christie (1966) Raven's Cry. New York: Atheneum.

- Harrison, Charles (1925) Ancient Warriors of the North Pacific - The Haidas, Their Laws, Customs and Legends. H.F. & G. Witherby.

- Huteson, Pamela (2007) "Transformation Masks" Surrey, B.C. Canada: Hancock House Publishers LTD. ISBN 978-0-88839-635-8

- Kan, Sergei (1993) SYMBOLIC IMMORTALITY; The Tlingit Potlatch of the Nineteenth Century Smithsonian.

- Snyder, Gary (1979) He Who Hunted Birds in His Father's Village. San Francisco: Grey Fox Press.

- Stearns, Mary Lee (1981) Haida Culture in Custody: The Masset Band. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- The Hydah mission, Queen Charlotte's Islands: an account of the mission and people, with a descriptive letter, Rev. Charles Harrison, publ. Church Missionary Society/Seeley, Jackson & Halliday, London, England, 1884.

- Yahgulanaas, Michael Nicoll (2008) "Flight of the Hummingbird" Vancouver; Greystone Books.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Haida people. |

- Haida at Curlie

- Central Council Tlingit Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska website

- The Haida - The Canadian Museum of Civilization

- Native Americans for Kids

- "Haida". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Haida". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "About Us". Petroglyph Gallery.

- "Haida masks". American Museum of Natural History.

- "Transformation masks". Khan Academy.

- "Social Organization". Canada Museum of History.

- "Tsimshian Society and Culture - Wealth and Rank - Feasts and Potlatches". Canada Museum of History.

- "Civilization.ca - Haida - Haida villages - Warfare". Canada Museum of History. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "The Northwest Coastal People - Religion / Ceremonies / Art / Clothing". firstpeoplesofcanada.com. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- Council, Old Massett Village. "A Relationship with Nature". virtualmuseum.ca. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Basketry". American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Tlingit & Haida - About Us - History". www.ccthita.org. Retrieved 11 December 2019.